ABSTRACT

Stigma refers to societally-deemed inferiority associated with a circumstance, behavior, status, or identity. It manifests internally, interpersonally, and structurally. Decades of research indicate that all forms of stigma are associated with heightened risk for mental health problems (e.g., depression, PTSD, suicidality) in stigmatized youth (i.e., children, adolescents, and young adults with one or more stigmatized identities, such as youth of Color and transgender youth). Notably, studies find that stigmatized youth living in places with high structural stigma – defined as laws/policies and norms/attitudes that hurt stigmatized people – have a harder time accessing mental health treatment and are less able to benefit from it. In order to reduce youth mental health inequities, it is imperative for our field to better understand, and ultimately address, stigma at each of these levels. To facilitate this endeavor, we briefly review research on stigma and youth mental health treatment, with an emphasis on structural stigma, and present three future directions for research in this area: (1) directly addressing stigma in treatment, (2) training therapists in culturally responsive care, and (3) structural interventions. We conclude with recommendations for best practices in broader mental health treatment research.

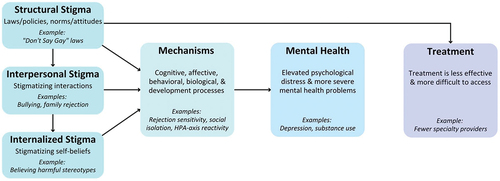

Now more than ever, stigmatized youth (i.e., children, adolescents, and young adults with one or more stigmatized identities; e.g., youth of Color, girls, transgender youth) are in need of effective mental health treatment. Inequities in mental health problem severity, diagnosis, and treatment between stigmatized and privileged groups (e.g., youth of Color vs. White youth, lesbian, gay, bisexual, or other sexual minority vs. heterosexual youth) are longstanding (Alegria et al., Citation2010; Bui & Takeuchi, Citation1992; Connolly et al., Citation2016; Garland et al., Citation2005; Rodgers et al., Citation2022; Russell & Fish, Citation2016), and these gaps are widening in the ongoing pandemic (Banks & Hsu, Citation2021; Benton et al., Citation2022; Bhogal et al., Citation2021; Fish et al., Citation2020; Hawke et al., Citation2021; Mpofu, Citation2022; Penner et al., Citation2021; Rothe et al., Citation2021; Saunders et al., Citation2021). These inequities are primarily attributable to these youth’s experiences of stigma at multiple levels: (1) internalized stigma (i.e., self-stigma), or one’s adoption of stigma-related beliefs resulting from exposure to stigmatizing environments or relationships (e.g., a girl believing that being assaulted was because of her physical attractiveness; Moses, Citation2009); (2) interpersonal stigma, which stigmatized individuals experience in interpersonal interactions (e.g., a peer saying “no homo”; sexual violence against girls; Fish, Citation2020; Jones & Neblett, Citation2017); and (3) structural stigma, or laws/policies (e.g., a state policy prohibiting gender-affirming care for transgender youth) and norms/attitudes (e.g., the belief that Black people will bring violence into neighborhoods they move into; Krieger et al., Citation2010) that negatively impact stigmatized people (Alvarez et al., Citation2021; Beccia et al., Citation2022; Castro-Ramirez et al., Citation2021; Hatzenbuehler, Citation2017).

Research consistently documents associations between internalized and interpersonal forms of stigma and mental health problems in multiple groups of stigmatized youth (e.g., youth of Color, girls, sexual minority youth; Bailey et al., Citation2022; Butler-Barnes et al., Citation2022; Chodzen et al., Citation2019; Price-Feeney et al., Citation2021; Reed et al., Citation2019; Rogers et al., Citation2022; Watson et al., Citation2019; Weeks & Sullivan, Citation2019). Relatively fewer studies with youth have examined structural stigma, but scholars have found associations between structural stigma and youth mental health (e.g., anxiety, depression, suicidality; Beccia et al., Citation2022; Duncan & Hatzenbuehler, Citation2014; Hatzenbuehler, Citation2011; Hatzenbuehler & Keyes, Citation2013; Saewyc et al., Citation2020; Torres et al., Citation2018) and behavioral health concerns (e.g., smoking, alcohol/substance use; Eisenberg et al., Citation2020; Hatzenbuehler et al., Citation2014, Citation2015; Watson et al., Citation2021, Citation2020). Studies also suggest that structural stigma may shape an array of cognitive (e.g., internalized stigma, rejection sensitivity; Pachankis, Hatzenbuehler et al., Citation2021; Pachankis et al., Citation2014), behavioral (e.g., identity concealment, social isolation; Pachankis & Bränström, Citation2018; Pachankis, Hatzenbuehler et al., Citation2021), biological (e.g., HPA-axis reactivity; Hatzenbuehler & McLaughlin, Citation2014), and developmental (e.g., neurodevelopment; Hatzenbuehler et al., Citation2021) processes in stigmatized young people.

Additionally, stigmatized youth in communities with higher (vs. lower) levels of structural stigma are more likely to experience interpersonal stigma (e.g., discrimination, bullying; Lessard et al., Citation2022; Renley et al., Citation2022; Van der Star et al., Citation2021; Watson et al., Citation2021), which may, in turn, increase their risk for internalized stigma (e.g., Boyes et al., Citation2020) and mental health difficulties (e.g., Seaton et al., Citation2022). Strikingly, emerging studies find that structural stigma is strongly associated with mental health treatment effectiveness (M. A. Price, McKetta et al., Citation2021; M. A. Price, Weisz et al., Citation2022) and access (Hollinsaid et al., Citation2022; Roulston et al., Citation2022) for stigmatized youth (see for a depiction of this multilevel mechanistic process). The present paper provides a brief overview of the scientific literature on structural stigma and youth mental health treatment, and details three future research directions we hope readers pursue. We conclude with recommendations for broader mental health treatment research to support further scientific progress in this area.

Structural Stigma and Mental Health Treatment Efficacy and Access

Two recent meta-analyses found that higher structural stigma – specifically, sexist and racist attitudes (separately) aggregated to the state level – was associated with lower psychotherapy efficacy for girls (M. A. Price, McKetta et al., Citation2021) and Black youth (M. A. Price, Weisz et al., Citation2022), respectively. In other words, girls and Black youth fared worse in therapy when they lived in states with higher (vs. lower) levels of structural stigma. Although these studies were unable to test mechanisms that might explain why therapy efficacy was worse for stigmatized youth in high stigma states, M. A. Price et al. (Citation2022) showed that Black youth’s treatment response was similar across states immediately after treatment ended, but significantly worse at follow-up (e.g., 6 months after ending treatment) in high (vs. low) racism states. In other words, this finding suggests that, once treatment ends, time spent living in a highly racist environment erodes treatment benefits for Black youth. Notably, this result was consistent with a similar spatial meta-analysis on anti-Black structural racism and HIV intervention efficacy, which found that efficacy also weakened over time in high racism communities (Reid et al., Citation2014). Taken together, these studies suggest that structural stigma may predict where and for whom youth mental treatment is effective. More specifically, the context in which treatments are tested, coupled with the identities of youth in treatment, are important and understudied sources of treatment-effect heterogeneity.

Emerging research also indicates that stigmatized youth may be less able to access mental health treatment if they live in high stigma environments (e.g., states with more restrictive laws/policies targeting transgender people’s rights), even when accounting for other structural factors (e.g., income inequality). In a large sample of sexual minority youth of Color, Roulston et al. (Citation2022) found that structural homophobia and racism were strongly associated with treatment access, such that sexual minority youth of Color living in states with more homophobic and racist attitudes reported being less likely to access treatment, even when controlling for mental health provider availability. Likewise, Hollinsaid et al. (Citation2022) documented substantially lower rates of mental health providers who specialize in providing services to transgender youth in states with more transphobic laws/policies while controlling for other state-level factors, such as political and religious conservatism. Similar studies have also identified a dearth of gender-affirming assessment materials (e.g., inclusive online intake forms; Holt et al., Citation2019, Citation2021), fewer referrals for gender-affirming services for transgender youth (Indremo et al., Citation2022), and less affirming services for sexual minority and transgender young people (Campbell & Mena, Citation2021) in places with high levels of structural stigma. In sum, research suggests that structural stigma not only increases stigmatized youth’s need for mental health treatment by worsening their mental health but also makes it harder for them to access and benefit from treatment.

In our increasingly diverse yet intolerant society, it is imperative to address the mental health needs of stigmatized youth. Doing so requires scientific progress resulting in improved youth mental health treatment efficacy and access. We propose three future directions to advance this research, each of which addresses stigma at all three levels (internalized, interpersonal, and structural). The first addresses treatment efficacy, and the final two address both treatment efficacy and access (see overview in ):

Directly address stigma in youth mental health treatment

Train therapists in culturally responsive care

Develop, test, and implement structural interventions (i.e., changing the environment itself)

Table 1. Overview of future directions in mental health treatment with stigmatized youth.

We provide exemplar studies within each future direction and specific suggestions that we hope enable researchers to conduct this much-needed research.

Future Direction #1: Directly Address Stigma in Treatment

Structural stigma is associated with a range of negative mental health problems in stigmatized youth (e.g., anxiety, depression, substance use; Hatzenbuehler, Citation2017), and research has uncovered individual (e.g., rejection sensitivity; Pachankis et al., Citation2014) and interpersonal (e.g., bullying, discrimination; Lessard et al., Citation2022; Watson et al., Citation2021) stigma processes, or mechanisms, by which structural stigma may increase risk for mental health problems (see ). Fortunately, there is growing evidence that mental health treatments can target some of these factors (e.g., Austin et al., Citation2018; Craig, Eaton et al., Citation2021; Pachankis et al., Citation2015), which may improve mental health outcomes for stigmatized youth. In fact, studies suggest that interventions that directly address experiences of internalized and/or interpersonal stigma may be more effective for those who experience more stigma (Lee et al., Citation2019; Pachankis et al., Citation2020). Accordingly, treatments that address stigma (at one or more levels) may be more efficacious in places with high structural stigma (Hatzenbuehler & Pachankis, Citation2021). In this section, we briefly review literature on treatments that directly target stigma and conclude with recommendations for future treatment research.

Treatments addressing client-level stigma range in scope (e.g., a self-administered brief online intervention, a multi-session treatment protocol) and focus (e.g., targeting internalized stigma vs. interpersonal skills). Though most treatments of this kind were developed for sexual minority and/or transgender clients (for a review, see Layland et al., Citation2020), promising interventions targeting internalized and interpersonal stigma related to race (e.g., Anderson et al., Citation2019), ethnicity (Kennard et al., Citation2020), and girl/woman identity (Bryant-Davis, Citation2019) have been developed more recently. Treatments in this category may be entirely novel treatment protocols (e.g., EMBRace; Anderson et al., Citation2019) or adapted from existing treatments (e.g., AFFIRM; Austin et al., Citation2018; Craig, Eaton et al., Citation2021; Craig, Leung et al., Citation2021; Craig & Austin, Citation2016; EQuIP; Pachankis et al., Citation2015).

These treatments are often rooted in minority stress theory (Brooks, Citation1981; Meyer, Citation2003), which posits that stigmatized individuals’ heightened risk for mental health concerns are attributable to chronic stigma-related stressors (e.g., discrimination, victimization) and stress processes (e.g., expectations of rejection). Examples of treatment components include psychoeducation on individual, interpersonal, and structural stigma and their mental health consequences (e.g., Craig & Austin, Citation2016), cognitive strategies to challenge internalized stigma (Austin et al., Citation2018), expressive writing and self-affirmation to address the effects of interpersonal stigma (e.g., family rejection, victimization; Pachankis et al., Citation2020), coping skills for actively attending to feelings during stigma encounters (e.g., mindfulness; Anderson et al., Citation2019), and assertiveness training for interpersonal stigma experiences (e.g., Pachankis et al., Citation2015).

Results from the relatively few pilot studies and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of youth mental health treatments targeting stigma demonstrate promising effects (Anderson et al., Citation2018; Lucassen et al., Citation2015; Pachankis et al., Citation2020). Importantly, many of these interventions involve only minimal changes to existing evidence-based treatments (e.g., incorporating the minority stress model into a CBT module on psychoeducation), and they are often delivered digitally and/or in few sessions (Craig, Leung et al., Citation2021; Pachankis et al., Citation2020) – increasing their scalability. Practice-informed literature on longstanding treatments addressing stigma (e.g., feminist psychotherapy; Arczynski & Morrow, Citation2017; L. S. Brown, Citation2006; Conlin, Citation2017; Gorey et al., Citation2001) and methods of adapting common treatments to address stigma (e.g., DBT; Skerven et al., Citation2019) are also useful resources for clinicians and researchers.

We recommend that researchers interested in treatments targeting stigma focus their efforts in the following areas:

Develop and test brief and scalable interventions that address stigma. Doing so might involve the development of entirely new protocols or the adaptation of single-session online interventions to directly target stigma and its effects (Schleider et al., Citation2020). Such interventions may serve as effective standalone treatment options (e.g., Pachankis et al., Citation2020) or augment existing treatments.

Test (e.g., in RCTs) and quickly scale existing interventions targeting stigma, particularly in places with high structural stigma, given stigma’s likely role as a mechanism of mental health problems in stigmatized youth and their promising effects for young people with high levels of interpersonal and individual stigma (see Hatzenbuehler & Pachankis, Citation2021 for a review).

Identify the most effective elements of interventions that address stigma through dismantling studies (e.g., Resick et al., Citation2008), which can then be disseminated widely via therapist training programs and/or translated into single-session interventions.

Examine whether high structural stigma attenuates the effects of treatments targeting stigma (Hatzenbuehler & Pachankis, Citation2021). While spatial meta-analytic techniques may not yet be appropriate given the relatively few trials completed to date (i.e., meta-analyses may be under-powered if conducted in the near future), those conducting intervention trials should strategically recruit stigmatized youth living in communities with varying levels of structural stigma. This could be accomplished by conducting multisite intervention trials or online intervention trials with national samples (e.g., Schleider et al., Citation2022).

For researchers already developing and testing interventions targeting stigma, administer measures of targeted mechanisms (e.g., internalized stigma, social isolation) and factors that may hinder or bolster treatment progress (e.g., interpersonal stigma exposure, therapeutic alliance; Bailey et al., Citation2011; Birkett et al., Citation2015; Bockting et al., Citation2020; Hidalgo et al., Citation2019; M. A. Price, Hollinsaid et al., Citation2021; Williams et al., Citation2008). Collect and publish ample detail on the content of interventions (e.g., which elements were adapted) and the location of participants to facilitate subsequent spatial meta-analyses.

Future Direction #2: Train Therapists in Culturally Responsive Practice

While addressing stigma in treatment may enhance treatment benefits for stigmatized youth, such improvements will only be useful if stigmatized youth can access treatment from adequately trained therapists. Scholarship on culturally responsive practice (i.e., multicultural or cultural competence) emerged in the 1940s and proliferated in the 1990s and early 2000s (Singh et al., Citation2020; Sue et al., Citation1992). Though emphases on culturally responsive practice vary across helping professions, accrediting bodies (e.g., American Psychological Association, Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs, National Association of Social Workers) overseeing therapist training programs require at least some education in “diversity” as it pertains to mental health treatment (Siegel et al., Citation2010). Such training varies widely across disciplines (e.g., social work, clinical psychology) and specific training programs (Devine & Ash, Citation2022; Galán et al., Citation2021; Gee et al., Citation2021; Najdowski et al., Citation2020; Pieterse et al., Citation2009). As a result, many therapists are under-prepared to meet the needs of youth with stigmatized identities (e.g., Abreu et al., Citation2020). For instance, studies suggest that few therapists have the knowledge and skills necessary to adequately support transgender youth and their families (M. A. Price, Bokhour et al., Citation2022; Strauss et al., Citation2021). Therapists’ lack of competency may increase their likelihood of discriminating against clients in the therapy room (e.g., microaggressions, stereotyping, misgendering) – a common treatment experience for stigmatized youth and adults (Compton & Morgan, Citation2022; Morris et al., Citation2020; Nadal et al., Citation2016; Yeo & Torres-Harding, Citation2021), including sexual minority and transgender youth (Chong et al., Citation2021; Forsythe et al., Citation2022; M. A. Price, Bokhour et al., Citation2022; Strauss et al., Citation2021) and youth of Color (Fadus et al., Citation2020; Fante-Coleman & Jackson-Best, Citation2020; Malone et al., Citation2021).

Taken together, this evidence suggests that existing training curricula in culturally responsive practice do not adequately address the mental health needs of stigmatized youth. This problem stems from both insufficient curricula (e.g., they are often developed solely by researchers, rather than by, or with, the client populations we seek to serve) and limited dissemination (i.e., the extent to which these curricula are distributed; Brownson et al., Citation2021; Lelutiu-Weinberger et al., Citation2022; Pachankis, Clark et al., Citation2021). Moreover, there is a dearth of research on the efficacy of such training. In other words, it is unclear whether training in culturally responsive care results in therapists using the practices they are taught, and the extent to which the use of those practices improves client experiences and mental health outcomes (Bettergarcia et al., Citation2021; Budge & Moradi, Citation2018; Chandler et al., Citation2022; Pachankis, Citation2018; E. G. Price et al., Citation2005). To address this gap, we recommend the following:

Develop therapist trainings that are useful to a variety of clinicians rather than specific to therapists who only use a particular treatment modality or work with a specific population (Pachankis et al., Citation2022). Doing so should involve teaching knowledge and skills that are applicable to a wide range of clients, such as directly addressing stigma in therapy (e.g., how to provide psychoeducation on internalized stigma).

Work closely with relevant community stakeholders using community-engaged methods (i.e., involving community members throughout the development, refinement, and testing of a new program) to develop therapist training programs (e.g., Allison et al., Citation2019). Doing so ensures that the trainings are designed to meet the needs of both clients and therapists, enhancing the likelihood that they are efficacious (i.e., likelihood of resulting in therapist behavior change and client satisfaction) and successfully implemented. Specifically, therapist training program development should involve the target client population (i.e., those who should ultimately benefit from being treated by trained therapists), the target therapist population (i.e., those most likely to work with the target population), and other relevant stakeholders (e.g., clients’ family members, clinic administrators, policymakers; M. A. Price, Citation2022).

Refine and test therapist training programs efficiently using methods designed to address and overcome implementation barriers, such as human-centered design (HCD; i.e., user centered design, design thinking), a method to develop and improve interventions by systematically incorporating input from key stakeholders and settings in which the interventions will ultimately be used (Lyon et al., Citation2020; Lyon & Koerner, Citation2016).

Create scalable therapist training programs by delivering them online or via apps (e.g., Lelutiu-Weinberger et al., Citation2022) to address widespread shortages in therapists with competency in culturally responsive care.

Assess the effects of training on both therapist and client outcomes to examine whether (or not) the target population benefits. While most studies of therapist training programs examine proximal effects on therapists (e.g., increased knowledge, attitudinal changes), very few studies assess whether or not clients experience any benefits (e.g., better mental health outcomes, stronger therapeutic alliance) from working with trained (vs. untrained) therapists. Assessing client outcomes among those working with trained therapists will provide information about the reach of the training program, and ultimately clarify whether the target population (e.g., stigmatized youth and their caregivers) truly benefits from therapist training efforts.

Examine and utilize implementation data throughout the development and testing process to facilitate later dissemination. In addition to examining effectiveness outcomes for therapists and clients (outlined above), we recommend collecting comprehensive implementation data (e.g., acceptability, appropriateness) from multiple stakeholders (e.g., clinicians, administrators) using multiple methods, such as self-report surveys, individual qualitative interviews, and objective measures (e.g., time spent interacting with online training app). These data should be analyzed and utilized to iteratively improve the training program throughout and after development (Dopp et al., Citation2019).

Future Direction #3: Structural Interventions

Targeting stigma in the environment will make treatments maximally effective for stigmatized youth (Blankenship et al., Citation2006; Hartog et al., Citation2020). Structural interventions aim to reduce stigma in institutions (e.g., schools), as well as in communities, states, or other geographic levels (Chaudoir et al., Citation2017; Cook et al., Citation2014). These interventions include efforts to change policies (e.g., implementing inclusive school/state anti-bullying policies; (Hatzenbuehler & Keyes, Citation2013; Kull et al., Citation2016), attitudes (e.g., increasing knowledge about stigmatized youth’s experiences to reduce prejudice; Grapin et al., Citation2019), physical spaces (e.g., building more accessible school playgrounds; D. M. Y. Brown et al., Citation2021), or access to resources (e.g., increasing the availability of sexual health services; Clermont et al., Citation2020). Structural interventions may have widespread and enduring benefits for stigmatized youth (Hartog et al., Citation2020) – improving mental health and perhaps even treatment access. In this section, we provide examples of structural interventions targeting stigma in schools, communities, and in the form of laws/policies, and recommend relevant research within each category.

Schools

Efforts to improve school climates for stigmatized youth are among the most common structural interventions, with many aimed at reducing stigma-based bullying (Earnshaw et al., Citation2018). These interventions can be universal (i.e., including the whole school) or targeted (e.g., focused solely on bullying victims; Fraguas et al., Citation2021), and often involve schoolwide discussions of anti-bullying policies, trainings on how to stop bullying (e.g., bystander interventions; Polanin et al., Citation2012), and education on stigmatized youth’s needs and experiences. Often, these interventions include contact between stigmatized and non-stigmatized individuals (e.g., through role-plays, presentations) and strategies to improve social or emotional skills (e.g., communication, self-control) for youth who bully others (Earnshaw et al., Citation2018). Other school-based interventions focus on reducing prejudicial attitudes among students and teachers through media (e.g., film; Burk et al., Citation2018; Sanz-Barbero et al., Citation2022). Substantial evidence suggests that school-based anti-bullying and anti-prejudice interventions decrease school bullying and foster more positive feelings toward stigmatized youth, including sexual minority and transgender youth (Burk et al., Citation2018), girls (Sanz-Barbero et al., Citation2022; Spinner et al., Citation2021), youth of Color (Aboud et al., Citation2012; Grapin et al., Citation2019), and refugee and migrant youth (Gabrielli et al., Citation2022).

Other school-based structural interventions provide stigmatized youth with sources of support and connectedness – whether through allyship with non-stigmatized youth or similarly stigmatized youth. For instance, starting a gender-sexuality alliance (GSA) may drastically improve school climate and support for sexual minority and transgender youth (e.g., Day et al., Citation2020). GSAs are consistently associated with reduced interpersonal stigma (e.g., victimization; Marx & Kettrey, Citation2016), better mental health (Baams & Russell, Citation2021; Poteat et al., Citation2020, Citation2021), and greater peer and teacher support (Day et al., Citation2020). Similarly, racial affinity groups offer students of Color a safe and supportive space to process experiences of racial discrimination and trauma (Oto & Chikkatur, Citation2019; Tauriac et al., Citation2013). Another example is the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) on Campus High School Clubs, which involve student-led efforts to increase mental health literacy and reduce mental health stigma in schools (National Alliance on Mental Illness [NAMI], Citation2021). However, relative to GSAs, the benefits of these programs have not been evaluated at the structural level, so it is unclear whether stigmatized youth who attend schools with vs. without such programs report better mental health. We recommend the following for research on school-based structural interventions:

Evaluate whether the presence of school allyship programs beyond GSAs (e.g., Black Student Unions) are effective in improving outcomes for stigmatized youth (e.g., mental health, rates of stigma-based bullying).

When evaluating school-based structural interventions, assess a wider range of outcomes, including school-related outcomes (e.g., attendance, grades) and covert stigma-related outcomes (e.g., microaggressions, cyberbullying).

Identify the most effective implementation strategies for, and components of, structural interventions in schools. For instance, researchers might consider questions such as: Who should these interventions target (e.g., students and staff, only students, only students who bully others) in order to be maximally effective? What is the optimal duration and frequency of these interventions? What are the most advantageous formats for delivering these interventions (e.g., classroom, school-wide assembly)?

Given recent efforts in some states to prohibit discussions of race, sexual, and/or gender identity in schools (e.g., “Don’t Say Gay” laws), it may be necessary to consider whether general anti-bullying interventions help stigmatized youth. Accordingly, we recommend examining whether general anti-bullying programs (i.e., focused on reducing school bullying regardless of motivation; Merrell et al., Citation2008) impact stigma-related outcomes (e.g., stigmatized youth’s mental health, rates of stigma-based bullying).

Communities

In high stigma communities, stigmatized youth may not have access to needed health services (Clermont et al., Citation2020) or support (e.g., family/peer support; Fish et al., Citation2019). Accordingly, many structural interventions aim to increase stigmatized youth’s access to community-based resources (e.g., sexual health services; Clermont et al., Citation2020; M. L. Ybarra et al., Citation2017, Citation2020; M. Ybarra et al., Citation2021) and support (e.g., LGBTQ community centers; Wilkerson et al., Citation2018). Other structural intervention focus on increasing access to physical spaces – for instance, by creating accessible play spaces for youth with disabilities (D. M. Y. Brown et al., Citation2021; Wenger et al., Citation2021) or by encouraging community members (e.g., business owners, health providers) to create and label supportive physical locations (e.g., safe spaces in healthcare settings; Evans, Citation2002; Finkel et al., Citation2003; Frye et al., Citation2017; Wheeler Black et al., Citation2012). Finally, a few interventions focus on changing community attitudes specific to stigmatized youth; those that do are most common outside the US (for reviews, see Hartog et al., Citation2020; Smythe et al., Citation2020). The following are recommendations for community-based structural interventions:

Determine how community-based structural interventions are best brought to scale – particularly in communities without supportive resources, or where interventions emphasizing intergroup contact may be invalidating or even harmful for stigmatized youth. Brief electronic social contact interventions (e.g., watching a two-minute video of a stigmatized youth sharing information on their identity and stigma experiences; Amsalem et al., Citation2022; Martin et al., Citation2022) represent one promising and readily scalable alternative, but they have yet to be tested at the community level.

To date, the effectiveness of community-based structural interventions has largely been assessed using self-report measures completed solely by those who completed the intervention (Michaels & Corrigan, Citation2013). To objectively assess change in attitudes in the larger community, scholars should analyze publicly available datasets such as Project Implicit – an ongoing, large-scale effort to assess individual explicit and implicit attitudes toward a variety of stigmatized identities (Xu et al., Citation2013). Project Implicit respondents include hundreds of thousands of individuals from communities across the US over decades, allowing researchers to measure community-level attitudes by aggregating data to the desired geographic level (e.g., county, city) and compare attitudes before and after the intervention.

Laws/Policies

Numerous structural interventions seek to change exclusionary laws/policies – most often at the state level. One of the most widely examined approaches is the passage of legislation extending rights to stigmatized groups (e.g., including gender identity in nondiscrimination laws/policies). In addition to the legal protections afforded by these policies, quasi-experimental research reveals that stigmatized youth experience myriad benefits from their passage, such as reduced mental health problems and treatment needs (McDowell et al., Citation2020). Alternatively, supportive state laws/policies can be adopted directly by voters through referendums. Although this approach is not as well studied as legislation, at least one study documented reductions in bullying for sexual minority youth following the approval of a same-gender marriage referendum in California (Hatzenbuehler et al., Citation2019). Because referendums often involve collective activism among stigmatized groups (e.g., engaging in demonstrations to raise awareness), they may have other benefits for stigmatized youth, such as increasing pride, self-efficacy, and connectedness (Flores et al., Citation2018). Litigation represents another promising strategy – with research showing that homophobic bullying decreased in California schools where students were successful in discrimination-related court cases (Hatzenbuehler et al., Citation2022). Future research in this area should:

Assess a wider array of structural intervention outcomes, including outcomes related to mental health treatment access. For example, researchers might consider: Does the implementation of more supportive institutional policies and practices (e.g., including pronouns on name badges for community health center staff) increase the number of stigmatized youth using services? Does the implementation of supportive state laws/policies increase help-seeking behaviors for stigmatized youth and/or the availability of specialty mental health providers? Alternatively, is it possible that enacting supportive state laws/policies may reduce the number of stigmatized youth needing treatment by reducing their mental health concerns?

Much of the extant research on the effects of laws/policies on youth mental health focuses on sexual minority and/or transgender youth. Future studies should examine the effects of law/policies relevant to other stigmatized groups. For example, researchers should use quasi-experimental methods to assess whether the mental health of youth of Color improves following changes in school and/or district policies that disproportionately affect them, such as school policing or exclusionary discipline practices (Nance, Citation2016). Additional examples of discriminatory policies/laws that may affect stigmatized youth’s mental health include state abortion bans, sexual misconduct policies, and policies banning Critical Race Theory.

Summary and Recommendations for Broader Mental Health Treatment Research

The current article summarizes innovative research on youth mental health treatment for stigmatized youth and provides a roadmap for researchers interested in furthering progress in this area. We outline three broad areas for future research: directly addressing stigma in treatment, training therapists in culturally responsive care, and structural interventions. Within each area, we recommend specific actionable research approaches (summarized in ). We hope that the ideas outlined here inspire scientists to continue progressing toward a more equitable mental health treatment landscape for youth that ultimately serves to reduce mental health inequities. To improve our field’s ability to examine stigma in all intervention research, we conclude with recommendations for broader mental health treatment research:

To facilitate analyses of treatment outcomes for different stigmatized groups (e.g., Hollinsaid et al., Citation2020), recruit large and diverse samples of youth reflecting multiple stigmatized identities and comprehensively collect data on these identities (Kataoka et al., Citation2010; Lau et al., Citation2010; Santelli et al., Citation2003).

Publish data on participants’ identities (e.g., subsample sizes), intervention locations (e.g., zip code), and participant locations (e.g., the counties in which participants lived) in all intervention reports to enable researchers to conduct future spatial meta-analyses on structural stigma and mental health treatment efficacy (e.g., M. A. Price, McKetta et al., Citation2021; M. A. Price, Weisz et al., Citation2022).

Multisite intervention trials should be conducted in locations that are diverse with respect to structural stigma to facilitate research examining structural stigma as a moderator of treatment efficacy.

Administer measures of internalized stigma (e.g., Mak & Cheung, Citation2010), interpersonal stigma (e.g., identity-based bullying, discrimination; M. A. Price et al., Citation2019; Williams et al., Citation1997), and stigma-related processes (e.g., social isolation, rejection sensitivity) relevant to multiple groups to facilitate the identification of treatment-related moderators or mechanisms.

Examine whether treatment-related factors – such as therapeutic alliance, treatment duration, retention, and treatment satisfaction – are associated with treatment efficacy for stigmatized youth. For instance, researchers can use existing data from completed RCTs of traditional mental health interventions (i.e., that do not directly address stigma) with stigmatized youth subsamples or samples to explore differences in treatment experiences (e.g., Hollinsaid et al., Citation2020). Results may have implications for treatment development and testing and therapist training programs.

Stigmatized youth in low stigma (vs. high stigma) communities may respond more favorably to traditional mental health interventions. Identifying protective factors (e.g., family support, community connectedness) that predict treatment benefits for these youth (e.g., subsamples of youth of Color in ongoing RCTs) is another fruitful area of inquiry. Such work may reveal resources or strategies that – if made available to stigmatized youth in high stigma communities – may likewise improve their treatment response.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mr. Shuai (“Eddy”) Jiang for his help adding references and formatting this manuscript and Dr. Jonathan S. Jay for his thoughtful review and recommendations.

Disclosure Statement

Dr. Price has received grant or research support from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), the American Psychological Foundation, the Boston College School of Social Work Center for Social Innovation, the Boston College Schiller Institute for Integrated Science and Society, the Boston College Office of the Provost, and the Pershing Square Fund for the Harvard Foundations of Human Behavior. Mr. Hollinsaid has received grant or research support from the Boston Area Research Initiative.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aboud, F. E., Tredoux, C., Tropp, L. R., Brown, C. S., Niens, U., & Noor, N. M. (2012). Interventions to reduce prejudice and enhance inclusion and respect for ethnic differences in early childhood: A systematic review. Developmental Review, 32(4), 307–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2012.05.001

- Abreu, R., Kenny, M., Hall, J., & Huff, J. (2020). Supporting transgender students: School counselors’ preparedness, training efforts, and necessary support. Journal of LGBT Youth, 17(1), 107–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2019.1662755

- Alegria, M., Vallas, M., & Pumariega, A. J. (2010). Racial and ethnic disparities in pediatric mental health. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 19(4), 759–774. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2010.07.001

- Allison, M. K., Marshall, S. A., Archie, D. S., Neher, T., Stewart, G., Anders, M. E., & Stewart, M. K. (2019). Community-engaged development, implementation, and evaluation of an interprofessional education workshop on gender-affirming care. Transgender Health, 4(1), 280–286. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2019.0036

- Alvarez, K., Cervantes, P. E., Nelson, K. L., Seag, D. E. M., Horwitz, S. M., & Hoagwood, K. E. (2021). Review: Structural racism, children’s mental health service systems, and recommendations for policy and practice change. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, S0890-8567(21), 2091–2098. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2021.12.006

- Amsalem, D., Halloran, J., Penque, B., Celentano, J., & Martin, A. (2022). Effect of a brief social contact video on transphobia and depression-related stigma among adolescents: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Network Open, 5(2), e220376. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.0376

- Anderson, R. E., McKenny, M., Mitchell, A., Koku, L., & Stevenson, H. C. (2018). EMBRacing racial stress and trauma: Preliminary feasibility and coping responses of a racial socialization intervention. Journal of Black Psychology, 44(1), 25–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095798417732930

- Anderson, R. E., McKenny, M. C., & Stevenson, H. C. (2019). EMBRace: Developing a racial socialization intervention to reduce racial stress and enhance racial coping among Black parents and adolescents. Family Process, 58(1), 53–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12412

- Arczynski, A. V., & Morrow, S. L. (2017). The complexities of power in feminist multicultural psychotherapy supervision. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64(2), 192–205. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000179

- Austin, A., Craig, S. L., & D’Souza, S. A. (2018). An affirmative cognitive behavioral intervention for transgender youth: Preliminary effectiveness. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 49(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1037/pro0000154

- Baams, L., & Russell, S. T. (2021). Gay-straight alliances, school functioning, and mental health: Associations for students of color and LGBTQ students. Youth & Society, 53(2), 211–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X20951045

- Bailey, T.-K. M., Chung, Y. B., Williams, W. S., Singh, A. A., & Terrell, H. K. (2011). Development and validation of the internalized racial oppression scale for Black individuals. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58(4), 481–493. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023585

- Bailey, T.-K. M., Yeh, C. J., & Madu, K. (2022). Exploring Black adolescent males’ experiences with racism and internalized racial oppression. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64(4), 375–388. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000591

- Banks, A., & Hsu, M. J. (2021). Black adolescent experiences with COVID-19 and mental health services utilization. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 8(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-021-01049-w

- Beccia, A. L., Austin, S. B., Baek, J., Agénor, M., Forrester, S., Ding, E. Y., Jesdale, W. M., & Lapane, K. L. (2022). Cumulative Exposure to state-level structural sexism and risk of disordered eating: Results from a 20-year prospective cohort study. Social Science & Medicine, 301, 114956. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114956

- Benton, T., Njoroge, W. F. M., & Ng, W. Y. K. (2022). Sounding the alarm for children’s mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Pediatrics, 176(4), e216295. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.6295

- Bettergarcia, J., Matsuno, E., & Conover, K. J. (2021). Training mental health providers in queer-affirming care: A systematic review. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 8(3), 365–377. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000514

- Bhogal, A., Borg, B., Jovanovic, T., & Marusak, H. A. (2021). Are the kids really alright? Impact of COVID-19 on mental health in a majority Black American sample of schoolchildren. Psychiatry Research, 304, 114146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114146

- Birkett, M., Newcomb, M. E., & Mustanski, B. (2015). Does it get better? A longitudinal analysis of psychological distress and victimization in lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning youth. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(3), 280–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.10.275

- Blankenship, K., Friedman, S. R., Dworkin, S., & Mantell, J. (2006). Structural interventions: Concepts, challenges and opportunities for research. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 83(1), 59–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-005-9007-4

- Bockting, W. O., Miner, M. H., Swinburne Romine, R. E., Dolezal, C., Robinson, B. B. E., Rosser, B. R. S., & Coleman, E. (2020). The transgender identity survey: A measure of internalized transphobia. LGBT Health, 7(1), 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2018.0265

- Boyes, M. E., Pantelic, M., Casale, M., Toska, E., Newnham, E., & Cluver, L. D. (2020). Prospective associations between bullying victimisation, internalised stigma, and mental health in South African adolescents living with HIV. Journal of Affective Disorders, 276, 418–423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.101

- Brooks, V. R. (1981). Minority stress and lesbian women. Lexington Books.

- Brown, L. S. (2006). Still subversive after all these years: The relevance of feminist therapy in the age of evidence-based practice. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 30(1), 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2006.00258.x

- Brown, D. M. Y., Ross, T., Leo, J., Buliung, R. N., Shirazipour, C. H., Latimer-Cheung, A. E., & Arbour-Nicitopoulos, K. P. (2021). A scoping review of evidence-informed recommendations for designing inclusive playgrounds. Frontiers in Rehabilitation Sciences, 2. https://doi.org/10.3389/fresc.2021.664595

- Brownson, R. C., Kumanyika, S. K., Kreuter, M. W., & Haire-Joshu, D. (2021). Implementation science should give higher priority to health equity. Implementation Science, 16(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-021-01097-0

- Bryant-Davis, T. (2019). Multicultural feminist therapy: Helping adolescent girls of color to thrive. American Psychological Association.

- Budge, S. L., & Moradi, B. (2018). Attending to gender in psychotherapy: Understanding and incorporating systems of power. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(11), 2014–2027. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22686

- Bui, K. T., & Takeuchi, D. T. (1992). Ethnic minority adolescents and the use of community mental health care services. American Journal of Community Psychology, 20(4), 403–417. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00937752

- Burk, J., Park, M., & Saewyc, E. M. (2018). A media-based school intervention to reduce sexual orientation prejudice and its relationship to discrimination, bullying, and the mental health of lesbian, gay, and bisexual adolescents in western Canada: A population-based evaluation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(11), E2447. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112447

- Butler-Barnes, S. T., Leath, S., Inniss-Thompson, M. N., Allen, P. C., D’Almeida, M. E. D. A., & Boyd, D. T. (2022). Racial and gender discrimination by teachers: Risks for Black girls’ depressive symptomatology and suicidal ideation. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. No Pagination Specified-No Pagination Specified. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000538

- Campbell, C., & Mena, J. A. (2021). LGBTQ+ structural stigma and college counseling center website friendliness. Journal of College Counseling, 24(3), 241–255. https://doi.org/10.1002/jocc.12194

- Castro-Ramirez, F., Al-Suwaidi, M., Garcia, P., Rankin, O., Ricard, J. R., & Nock, M. K. (2021). Racism and poverty are barriers to the treatment of youth mental health concerns. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 50(4), 534–546. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2021.1941058

- Chandler, C. E., Williams, C. R., Turner, M. W., & Shanahan, M. E. (2022). Training public health students in racial justice and health equity: A systematic review. Public Health Reports, 137(2), 375–385. https://doi.org/10.1177/00333549211015665

- Chaudoir, S. R., Wang, K., & Pachankis, J. E. (2017). What reduces sexual minority stress? A review of the intervention “toolkit. The Journal of Social Issues, 73(3), 586–617. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12233

- Chodzen, G., Hidalgo, M. A., Chen, D., & Garofalo, R. (2019). Minority stress factors associated with depression and anxiety among transgender and gender-nonconforming youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 64(4), 467–471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.07.006

- Chong, L. S. H., Kerklaan, J., Clarke, S., Kohn, M., Baumgart, A., Guha, C., Tunnicliffe, D. J., Hanson, C. S., Craig, J. C., & Tong, A. (2021). Experiences and perspectives of transgender youths in accessing health care: A systematic review. JAMA Pediatrics, 175(11), 1159–1173. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2061

- Clermont, D., Gilmer, T., Burgos, J. L., Berliant, E., & Ojeda, V. D. (2020). HIV and sexual health services available to sexual and gender minority youth seeking care at outpatient public mental health programs in two California counties. Health Equity, 4(1), 375–381. https://doi.org/10.1089/heq.2020.0014

- Compton, E., & Morgan, G. (2022). The experiences of psychological therapy amongst people who identify as transgender or gender non-conforming: A systematic review of qualitative research. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952833.2022.2068843

- Conlin, S. E. (2017). Feminist therapy: A brief integrative review of theory, empirical support, and call for new directions. Women’s Studies International Forum, 62, 78–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2017.04.002

- Connolly, M. D., Zervos, M. J., Barone, C. J., Johnson, C. C., & Joseph, C. L. M. (2016). The mental health of transgender youth: Advances in understanding. Journal of Adolescent Health, 59(5), 489–495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.012

- Cook, J. E., Purdie-Vaughns, V., Meyer, I. H., & Busch, J. T. A. (2014). Intervening within and across levels: A multilevel approach to stigma and public health. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 103, 101–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.09.023

- Craig, S. L., & Austin, A. (2016). The AFFIRM open pilot feasibility study: A brief affirmative cognitive behavioral coping skills group intervention for sexual and gender minority youth. Children and Youth Services Review, 64, 136–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.02.022

- Craig, S. L., Eaton, A. D., Leung, V. W. Y., Iacono, G., Pang, N., Dillon, F., Austin, A., Pascoe, R., & Dobinson, C. (2021). Efficacy of affirmative cognitive behavioural group therapy for sexual and gender minority adolescents and young adults in community settings in Ontario, Canada. BMC Psychology, 9(1), 94. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-021-00595-6

- Craig, S. L., Leung, V. W. Y., Pascoe, R., Pang, N., Iacono, G., Austin, A., & Dillon, F. (2021). AFFIRM online: Utilising an affirmative cognitive–behavioural digital intervention to improve mental health, access, and engagement among LGBTQA+ youth and young adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), 1541. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041541

- Day, J. K., Fish, J. N., Grossman, A. H., & Russell, S. T. (2020). Gay-straight alliances, inclusive policy, and school climate: LGBTQ youths’ experiences of social support and bullying. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 30(S2), 418–430. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12487

- Devine, P. G., & Ash, T. L. (2022). Diversity training goals, limitations, and promise: A review of the multidisciplinary literature. Annual Review of Psychology, 73(1), 403–429. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-060221-122215

- Dopp, A. R., Parisi, K. E., Munson, S. A., & Lyon, A. R. (2019). Integrating implementation and user-centred design strategies to enhance the impact of health services: Protocol from a concept mapping study. Health Research Policy and Systems, 17(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-018-0403-0

- Duncan, D. T., & Hatzenbuehler, M. L. (2014). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender hate crimes and suicidality among a population-based sample of sexual-minority adolescents in Boston. American Journal of Public Health, 104(2), 272–278. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301424

- Earnshaw, V. A., Reisner, S. L., Menino, D. D., Poteat, V. P., Bogart, L. M., Barnes, T. N., & Schuster, M. A. (2018). Stigma-based bullying interventions: A systematic review. Developmental Review, 48, 178–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2018.02.001

- Eisenberg, M. E., Erickson, D. J., Gower, A. L., Kne, L., Watson, R. J., Corliss, H. L., & Saewyc, E. M. (2020). Supportive community resources are associated with lower risk of substance use among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and questioning adolescents in Minnesota. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(4), 836–848. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-01100-4

- Evans, N. J. (2002). The impact of an LGBT safe zone project on campus climate. Journal of College Student Development, 43(4), 522–539.

- Fadus, M. C., Ginsburg, K. R., Sobowale, K., Halliday-Boykins, C. A., Bryant, B. E., Gray, K. M., & Squeglia, L. M. (2020). Unconscious bias and the diagnosis of disruptive behavior disorders and ADHD in African American and Hispanic youth. Academic Psychiatry, 44(1), 95–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-019-01127-6

- Fante-Coleman, T., & Jackson-Best, F. (2020). Barriers and facilitators to accessing mental healthcare in Canada for Black youth: A scoping review. Adolescent Research Review, 5(2), 115–136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-020-00133-2

- Finkel, M. J., Storaasli, R. D., Bandele, A., & Schaefer, V. (2003). Diversity training in graduate school: An exploratory evaluation of the safe zone project. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 34(5), 555–561. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.34.5.555

- Fish, J. N. (2020). Future directions in understanding and addressing mental health among LGBTQ youth. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 49(6), 943–956. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2020.1815207

- Fish, J. N., McInroy, L. B., Paceley, M. S., Williams, N. D., Henderson, S., Levine, D. S., & Edsall, R. N. (2020). “I’m kinda stuck at home with unsupportive parents right now”: LGBTQ youths’ experiences with COVID-19 and the importance of online support. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(3), 450–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.06.002

- Fish, J. N., Moody, R. L., Grossman, A. H., & Russell, S. T. (2019). LGBTQ youth-serving community-based organizations: Who participates and what difference does it make? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(12), 2418–2431. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-01129-5

- Flores, A. R., Hatzenbuehler, M. L., & Gates, G. J. (2018). Identifying psychological responses of stigmatized groups to referendums. PNAS: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 115(15), 3816–3821. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1712897115

- Forsythe, A., Pick, C., Tremblay, G., Malaviya, S., Green, A., & Sandman, K. (2022). Humanistic and economic burden of conversion therapy among LGBTQ youths in the United States. JAMA Pediatrics, 176(5), 493–501. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.0042

- Fraguas, D., Díaz-Caneja, C. M., Ayora, M., Durán-Cutilla, M., Abregú-Crespo, R., Ezquiaga-Bravo, I., Martín-Babarro, J., & Arango, C. (2021). Assessment of school anti-bullying interventions: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Pediatrics, 175(1), 44–55. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.3541

- Frye, V., Paige, M. Q., Gordon, S., Matthews, D., Musgrave, G., Kornegay, M., Greene, E., Phelan, J. C., Koblin, B. A., & Taylor-Akutagawa, V. (2017). Developing a community-level anti-HIV/AIDS stigma and homophobia intervention in New York city: The project CHHANGE model. Evaluation and Program Planning, 63, 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2017.03.004

- Gabrielli, S., Catalano, M. G., Maricchiolo, F., Paolini, D., & Perucchini, P. (2022). Reducing implicit prejudice towards migrants in fifth grade pupils: Efficacy of a multi-faceted school-based program. Social Psychology of Education, 25(2–3), 425–440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-022-09688-5

- Galán, C. A., Bekele, B., Boness, C., Bowdring, M., Call, C., Hails, K., McPhee, J., Mendes, S. H., Moses, J., Northrup, J., Rupert, P., Savell, S., Sequeira, S., Tervo-Clemmens, B., Tung, I., Vanwoerden, S., Womack, S., & Yilmaz, B. (2021). Editorial: A call to action for an antiracist clinical science. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 50(1), 12–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2020.1860066

- Garland, A. F., Lau, A. S., Yeh, M., McCabe, K. M., Hough, R. L., & Landsverk, J. A. (2005). Racial and ethnic differences in utilization of mental health services among high-risk youths. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(7), 1336–1343. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1336

- Gee, D., DeYoung, K. A., McLaughlin, K. A., Tillman, R. M., Barch, D., Forbes, E. E., Krueger, R., Strauman, T. J., Weierich, M. R., & Shackman, A. J. (2021). Training the next generation of clinical psychological scientists: A data-driven call to action. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 2022, 18(1), 43–70. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/xq538

- Gorey, K. M., Daly, C., Richter, N. L., Gleason, D. R., & McCallum, M. J. A. (2001). The effectiveness of feminist social work methods: An integrative review. Journal of Social Service Research, 29(1), 37–55. https://doi.org/10.1300/J079v29n01_02

- Grapin, S. L., Griffin, C. B., Naser, S. C., Brown, J. M., & Proctor, S. L. (2019). School-based interventions for reducing youths’ racial and ethnic prejudice. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 6(2), 154–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/2372732219863820

- Hartog, K., Hubbard, C. D., Krouwer, A. F., Thornicroft, G., Kohrt, B. A., & Jordans, M. J. D. (2020). Stigma reduction interventions for children and adolescents in low- and middle-income countries: Systematic review of intervention strategies. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 246, 112749. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112749

- Hatzenbuehler, M. L. (2011). The social environment and suicide attempts in lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Pediatrics, 127(5), 896–903. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-3020

- Hatzenbuehler, M. L. (2017). Advancing research on structural stigma and sexual orientation disparities in mental health among youth. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 46(3), 463–475. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2016.1247360

- Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Jun, H.-J., Corliss, H. L., & Austin, S. B. (2014). Structural stigma and cigarette smoking in a prospective cohort study of sexual minority and heterosexual youth. Annals of Behavioral Medicine: A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 47(1), 48–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-013-9548-9

- Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Jun, H.-J., Corliss, H. L., & Austin, S. B. (2015). Structural stigma and sexual orientation disparities in adolescent drug use. Addictive Behaviors, 46, 14–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.02.017

- Hatzenbuehler, M. L., & Keyes, K. M. (2013). Inclusive anti-bullying policies and reduced risk of suicide attempts in lesbian and gay youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(1), S21–S26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.08.010

- Hatzenbuehler, M. L., McKetta, S., Kim, R., Leung, S., Prins, S. J., & Russell, S. T. (2022). Evaluating litigation as a structural strategy for addressing bias-based bullying among youth. JAMA Pediatrics, 176(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.3660

- Hatzenbuehler, M. L., & McLaughlin, K. A. (2014). Structural stigma and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis reactivity in lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Annals of Behavioral Medicine: A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 47(1), 39–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-013-9556-9

- Hatzenbuehler, M. L., & Pachankis, J. E. (2021). Does stigma moderate the efficacy of mental- and behavioral-health interventions? Examining individual and contextual sources of treatment-effect heterogeneity. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 30(6), 476–484. https://doi.org/10.1177/09637214211043884

- Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Shen, Y., Vandewater, E. A., & Russell, S. T. (2019). Proposition 8 and homophobic bullying in California. Pediatrics, 143(6), e20182116. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-2116

- Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Weissman, D. G., McKetta, S., Lattanner, M. R., Ford, J. V., Barch, D. M., & McLaughlin, K. A. (2021). Smaller hippocampal volume among Black and Latinx youth living in high-stigma contexts. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, S0890-8567(21), 1361–1367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2021.08.017

- Hawke, L., Hayes, E., Darnay, K., & Henderson, J. (2021). Mental health among transgender and gender diverse youth: An exploration of effects during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 8(2), 180–187. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000467

- Hidalgo, M. A., Petras, H., Chen, D., & Chodzen, G. (2019). The gender minority stress and resilience measure: Psychometric validity of an adolescent extension. Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology, 7(3), 278–290. https://doi.org/10.1037/cpp0000297

- Hollinsaid, N. L., Price, M. A., & Hatzenbuehler, M. L. (2022). Transgender-specific adolescent mental health provider availability is lower in states with more restrictive policies. OSF. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/zym53

- Hollinsaid, N. L., Weisz, J. R., Chorpita, B. F., Skov, H. E., Price, M. A., & Price, M. A. (2020). The effectiveness and acceptability of empirically supported treatments in gender minority youth across four randomized controlled trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 88(12), 1053–1064. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000597

- Holt, N. R., Hope, D. A., Mocarski, R., & Woodruff, N. (2019). First impressions online: The inclusion of transgender and gender nonconforming identities and services in mental healthcare providers’ online materials in the USA. International Journal of Transgenderism, 20(1), 49–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2018.1428842

- Holt, N. R., King, R. E., Mocarski, R., Woodruff, N., & Hope, D. A. (2021). Specialists in name or practice? The inclusion of transgender and gender diverse identities in online materials of gender specialists. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 33(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538720.2020.1763225

- Indremo, M., Jodensvi, A. C., Arinell, H., Isaksson, J., & Papadopoulos, F. C. (2022). Association of media coverage on transgender health with referrals to child and adolescent gender identity clinics in Sweden. JAMA Network Open, 5(2), e2146531. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.46531

- Jones, S. C. T., & Neblett, E. W. (2017). Future directions in research on racism-related stress and racial-ethnic protective factors for Black youth. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology: The Official Journal for the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, American Psychological Association, Division, 46(5), 754–766. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2016.1146991

- Kataoka, S., Novins, D. K., & DeCarlo Santiago, C. (2010). The practice of evidence-based treatments in ethnic minority youth. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 19(4), 775–789. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2010.07.008

- Kennard, B., Moorehead, A., Stewart, S., El-Behadli, A., Mbroh, H., Goga, K., Wildman, R., Michaels, M., & Higashi, R. T. (2020). Adaptation of group-based suicide intervention for Latinx youth in a community mental health center. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(7), 2058–2069. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-020-01718-0

- Krieger, N., Carney, D., Lancaster, K., Waterman, P. D., Kosheleva, A., & Banaji, M. (2010). Combining explicit and implicit measures of racial discrimination in health research. American Journal of Public Health, 100(8), 1485–1492. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.159517

- Kull, R., Greytak, E., Kosciw, J., & Villenas, C. (2016). Effectiveness of school district antibullying policies in improving LGBT youths’ school climate. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 3(4), 407–415. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000196

- Lau, A. S., Chang, D. F., & Okazaki, S. (2010). Methodological challenges in treatment outcome research with ethnic minorities. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16(4), 573–580. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021371

- Layland, E. K., Carter, J. A., Perry, N. S., Cienfuegos-Szalay, J., Nelson, K. M., Bonner, C. P., & Rendina, H. J. (2020). A systematic review of stigma in sexual and gender minority health interventions. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 10(5), 1200–1210. https://doi.org/10.1093/tbm/ibz200

- Lee, C. S., Colby, S. M., Rohsenow, D. J., Martin, R., Rosales, R., McCallum, T. T., Falcon, L., Almeida, J., & Cortés, D. E. (2019). A randomized controlled trial of motivational interviewing tailored for heavy drinking Latinxs. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 87(9), 815. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000428

- Lelutiu-Weinberger, C., Clark, K. A., & Pachankis, J. E. (2022). Mental health provider training to improve LGBTQ competence and reduce implicit and explicit bias: A randomized controlled trial of online and in-person delivery. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, No Pagination Specified-No Pagination Specified. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000560

- Lessard, L. M., Watson, R. J., Schacter, H. L., Wheldon, C. W., & Puhl, R. M. (2022). Weight enumeration in United States anti-bullying laws: Associations with rates and risks of weight-based bullying among sexual and gender minority adolescents. Journal of Public Health Policy, 43(1), 27–39. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41271-021-00322-w

- Lucassen, M. F. G., Merry, S. N., Hatcher, S., & Frampton, C. M. A. (2015). Rainbow SPARX: A novel approach to addressing depression in sexual minority youth. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22(2), 203–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2013.12.008

- Lyon, A. R., Brewer, S. K., & Areán, P. A. (2020). Leveraging human-centered design to implement modern psychological science: Return on an early investment. The American Psychologist, 75(8), 1067–1079. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000652

- Lyon, A. R., & Koerner, K. (2016). User-centered design for psychosocial intervention development and implementation. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 23(2), 180–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12154

- Mak, W. W. S., & Cheung, R. Y. M. (2010). Self-stigma among concealable minorities in Hong Kong: Conceptualization and unified measurement. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 80(2), 267–281. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01030.x

- Malone, C. M., Wycoff, K., & Turner, E. A. (2021). Applying a MTSS framework to address racism and promote mental health for racial/ethnic minoritized youth. Psychology in the Schools. n/a(n/a). https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22606

- Martin, A., Celentano, J., Olezeski, C., Halloran, J., Penque, B., Aguilar, J., & Amsalem, D. (2022). Collaborating with transgender youth to train healthcare professionals: Randomized controlled trial of a didactic enhanced by brief videos. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-1588004/v1

- Marx, R. A., & Kettrey, H. H. (2016). Gay-straight alliances are associated with lower levels of school-based victimization of LGBTQ+ youth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(7), 1269–1282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0501-7

- McDowell, A., Raifman, J., Progovac, A. M., & Rose, S. (2020). Association of nondiscrimination policies with mental health among gender minority individuals. JAMA Psychiatry. 77(9), 952–958. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.0770

- Merrell, K., Gueldner, B., Ross, S., & Isava, D. (2008). How effective are school bullying intervention programs? A meta-analysis of intervention research. School Psychology Quarterly, 23(1), 26–42. https://doi.org/10.1037/1045-3830.23.1.26

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

- Michaels, P., & Corrigan, P. (2013). Measuring mental illness stigma with diminished social desirability effects. Journal of Mental Health, 22(3), 218–226. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2012.734652

- Morris, E. R., Lindley, L., & Galupo, M. P. (2020). “Better issues to focus on”: Transgender microaggressions as ethical violations in therapy. The Counseling Psychologist, 48(6), 883–915. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000020924391

- Moses, T. (2009). Stigma and self-concept among adolescents receiving mental health treatment. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 79(2), 261–274. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015696

- Mpofu, J. J. (2022). Perceived racism and demographic, mental health, and behavioral characteristics among high school students during the COVID-19 pandemic—Adolescent behaviors and experiences survey, United States, January–June 2021. MMWR Supplements, 71(3), 22–27. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.su7103a4

- Nadal, K. L., Whitman, C. N., Davis, L. S., Erazo, T., & Davidoff, K. C. (2016). Microaggressions toward lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and genderqueer people: A review of the literature. Journal of Sex Research, 53(4–5), 488–508. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2016.1142495

- Najdowski, A., Gharapetian, L., & Jewett, V. (2020). Towards the development of antiracist and multicultural graduate training programs in behavior analysis. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 14(2), 462–477. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/384vr

- Nance, J. P. (2016). Students, police, and the school-to-prison pipeline. Washington Law Review, 93(4), 919–987. https://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/facultypub/766

- National Alliance on Mental Illness. (2021). NAMI on campus high school. https://namica.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/NCHS-Info-Packet.pdf

- Oto, R., & Chikkatur, A. (2019). “We didn’t have to go through those barriers”: Culturally affirming learning in a high school affinity group. The Journal of Social Studies Research, 43(2), 145–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssr.2018.10.001

- Pachankis, J. E. (2018). The scientific pursuit of sexual and gender minority mental health treatments: Toward evidence-based affirmative practice. The American Psychologist, 73(9), 1207–1219. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000357

- Pachankis, J. E., & Bränström, R. (2018). Hidden from happiness: Structural stigma, sexual orientation concealment, and life satisfaction across 28 countries. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 86(5), 403–415. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000299

- Pachankis, J. E., Clark, K. A., Jackson, S. D., Pereira, K., & Levine, D. (2021). Current capacity and future implementation of mental health services in U.S. LGBTQ community centers. Psychiatric Services, 72(6), 669–676. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.202000575

- Pachankis, J. E., Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Bränström, R., Schmidt, A. J., Berg, R. C., Jonas, K., Pitoňák, M., Baros, S., & Weatherburn, P. (2021). Structural stigma and sexual minority men’s depression and suicidality: A multilevel examination of mechanisms and mobility across 48 countries. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 130(7), 713–726. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000693

- Pachankis, J. E., Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Rendina, H. J., Safren, S. A., & Parsons, J. T. (2015). LGB-affirmative cognitive-behavioral therapy for young adult gay and bisexual men: A randomized controlled trial of a transdiagnostic minority stress approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(5), 875–889. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000037

- Pachankis, J. E., Hatzenbuehler, M. L., & Starks, T. J. (2014). The influence of structural stigma and rejection sensitivity on young sexual minority men’s daily tobacco and alcohol use. Social Science & Medicine, 103, 67–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.10.005

- Pachankis, J. E., Soulliard, Z. A., Morris, F., & Seager van Dyk, I. (2022). A model for adapting evidence-based interventions to be LGBT-affirmative: Putting minority stress principles and case conceptualization into clinical research and practice. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2021.11.005

- Pachankis, J. E., Williams, S. L., Behari, K., Job, S., McConocha, E. M., & Chaudoir, S. R. (2020). Brief online interventions for LGBTQ young adult mental and behavioral health: A randomized controlled trial in a high-stigma, low-resource context. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 88(5), 429–444. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000497

- Penner, F., Ortiz, J. H., & Sharp, C. (2021). Change in youth mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in a majority Hispanic/Latinx US sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 60(4), 513–523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2020.12.027

- Pieterse, A. L., Evans, S. A., Risner-Butner, A., Collins, N. M., & Mason, L. B. (2009). Multicultural competence and social justice training in counseling psychology and counselor education: A review and analysis of a sample of multicultural course syllabi. The Counseling Psychologist, 37(1), 93–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000008319986

- Polanin, J. R., Espelage, D. L., Pigott, T. D., & Betts, J. (2012). A meta-analysis of school-based bullying prevention programs’ effects on bystander intervention behavior. School Psychology Review, 41(1), 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2012.12087375

- Poteat, V. P., Calzo, J. P., Yoshikawa, H., Lipkin, A., Ceccolini, C. J., Rosenbach, S. B., O’Brien, M. D., Marx, R. A., Murchison, G. R., & Burson, E. (2020). Greater engagement in gender-sexuality alliances and GSA characteristics predict youth empowerment and reduced mental health concerns. Child Development, 91(5), 1509–1528. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13345

- Poteat, V. P., Watson, R. J., & Fish, J. N. (2021). Teacher support moderates associations among sexual orientation identity outness, victimization, and academic performance among LGBTQ+ youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(8), 1634–1648. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-021-01455-7

- Price, M. A. (2022). Development of a training intervention to improve mental health treatment for transgender and gender diverse youth. OSF. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/FV7JK

- Price-Feeney, M., Green, A. E., & Dorison, S. H. (2021). Impact of bathroom discrimination on mental health among transgender and nonbinary youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 68(6), 1142–1147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.11.001

- Price, E. G., Beach, M. C., Gary, T. L., Robinson, K. A., Gozu, A., Palacio, A., Smarth, C., Jenckes, M., Feuerstein, C., Bass, E. B., Powe, N. R., & Cooper, L. A. (2005). A systematic review of the methodological rigor of studies evaluating cultural competence training of health professionals. Academic Medicine, 80(6), 578–586. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200506000-00013

- Price, M. A., Bokhour, E. J., Hollinsaid, N. L., Kaufman, G. W., Sheridan, M. E., & Olezeski, C. L. (2022). Therapy experiences of transgender and gender diverse adolescents and their caregivers. Evidence-Based Practice in Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 7(2), 230–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/23794925.2021.1981177

- Price, M. A., Hill, N. E., Liang, B., & Perella, J. (2019). Teacher relationships and adolescents experiencing identity-based victimization: What matters for whom among stigmatized adolescents. School Mental Health, 11(4), 790–806. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-019-09327-z

- Price, M. A., Hollinsaid, N. L., Bokhour, E. J., Johnston, C., Skov, H. E., Kaufman, G. W., Sheridan, M., & Olezeski, C. (2021). Transgender and gender diverse youth’s experiences of gender-related adversity. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-021-00785-6

- Price, M. A., McKetta, S., Weisz, J. R., Ford, J. V., Lattanner, M. R., Skov, H., Wolock, E., & Hatzenbuehler, M. L. (2021). Cultural sexism moderates efficacy of psychotherapy: Results from a spatial meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 28(3), 299–312. https://doi.org/10.1037/cps0000031

- Price, M. A., Weisz, J. R., McKetta, S., Hollinsaid, N. L., Lattanner, M. R., Reid, A. E., & Hatzenbuehler, M. L. (2022). Meta-analysis: Are psychotherapies less effective for black youth in communities with higher levels of Anti-Black racism? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 61(6), 754–763. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2021.07.808

- Reed, E., Salazar, M., Agah, N., Behar, A. I., Silverman, J. G., Walsh-Buhi, E., Rusch, M. L. A., & Raj, A. (2019). Experiencing sexual harassment by males and associated substance use & poor mental health outcomes among adolescent girls in the US. SSM - Population Health, 9, 100476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100476

- Reid, A. E., Dovidio, J. F., Ballester, E., & Johnson, B. T. (2014). HIV prevention interventions to reduce sexual risk for African Americans: The influence of community-level stigma and psychological processes. Social Science & Medicine, 103, 118–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.028

- Renley, B. M., Burson, E., Simon, K. A., Caba, A. E., & Watson, R. J. (2022). Youth-specific sexual and gender minority state-level policies: Implications for pronoun, name, and bathroom/locker room use among gender minority youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 51(4), 780–791. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-022-01582-9

- Resick, P. A., Galovski, T. E., Uhlmansiek, M. O., Scher, C. D., Clum, G. A., & Young-Xu, Y. (2008). A randomized clinical trial to dismantle components of cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in female victims of interpersonal violence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(2), 243–258. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.243