ABSTRACT

Objective

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, Latinx youth report high rates of negative mental health outcomes such as anxiety and depression. Similarly, research with lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) youth have documented increased negative mental health outcomes such as depression and anxiety as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the current literature has yet to systematically uncover the intersectional experiences of Latinx LGBTQ youth during this time.

Method

We conducted a systematic review to uncover the experiences of Latinx LGBTQ youth during the pandemic. Our systematic review resulted in 14 empirical studies that explored the challenges, stressors, and impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Latinx LGBTQ youth.

Results

Findings revealed that most studies include cisgender, gender binary, heterosexual, Latinx youth. Findings across studies include: (a) impact from school closures, (b) pandemic stressors, (c) impact from online media, (d) family and Latinx cultural values as a source of support and stress, and (e) the implementation and evaluation of interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Discussion

We provide recommendations for clinicians working with Latinx LGBTQ youth including expanding their knowledge about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on these communities, considering the experiences of Latinx LGBTQ youth as multifaceted, and considering the role of heterogeneity in the mental health of Latinx LGBTQ Youth.

RESUMEN

Objectivo: Como resultado de la pandemia del COVID-19, los jóvenes Latines reportan altas tasas de síntomas negativos en su salud mental, incluyendo ansiedad y depresión. Del mismo modo, investigaciones con jóvenes lesbianas, gays, bisexuales, transgénero, y queer (LGBTQ) han documentado un impacto negativo en su salud mental tras la pandemia. Sin embargo, la literatura actual no ha revisado sistemáticamente las experiencias interseccionales de los jóvenes Latines LGBTQ durante este tiempo.

Método: Realizamos una revisión sistemática de la actual literatura enfocada en jóvenes Latines LGBTQ durante la pandemia para entender sus experiencias. Nuestra revision sistemática dio como resultado 14 estudios empíricos que exploraron los desafíos, factores estresantes, y el impacto de la pandemia del COVID-19 en los jóvenes Latines LGBTQ.

Resultados: Los hallazgos revelaron que la mayoría de los estudios incluyen jóvenes Latines cisgénero, binarios de género, y heterosexuales. Los resultados más comunes en estos estudios incluyen: (a) impacto del cierre de escuelas, (b) factores estresantes de la pandemia, (c) impacto de los medios en línea, (d) la familia y valores culturales Latines como fuente de apoyo y estrés, y (e) la implementación y evaluación de intervenciones durante la pandemia del COVID-19.

Discusión: Brindamos recomendaciones para los clínicos que trabajan con jóvenes Latines LGBTQ, incluyendo la ampliación de sus conocimientos sobre el impacto de la pandemia del COVID-19 en estas comunidades, considerando las experiencias de los jóvenes Latines LGBTQ como multifacéticas, y el papel de la heterogeneidad en la salud mental de la juventud Latine LGBTQ.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) youth experience increased negative mental health outcomes (e.g., depression, anxiety) compared to their cisgender and heterosexual counterparts (e.g., Abreu et al., Citation2022) due to cissexism and heterosexism. Cissexism refers to oppression enacted at the individual, institutional, and cultural level against people who identify or present as a different gender than the one assigned at birth (Hibbs, Citation2014). Heterosexism refers to oppression enacted at the individual, institutional, and cultural level against people with queer sexual identities (Collins, Citation2022). Similarly, Latinx youth in the United States are exposed to ethnic-based discrimination and harassment, leading to increased negative mental health outcomes such as depressive symptoms (e.g., Cardoso et al., Citation2018).

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the negative mental health impact for LGBTQ youth due to disruption in mental health services and having to return to unsupportive family members (e.g., Hawke et al., Citation2021). In addition, research shows that Latinx youth and their families have also been disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 pandemic (Torres et al., Citation2022). For instance, Latinx youth report high-stress levels, fear, isolation, and economic uncertainty due to the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., D’Costa et al., Citation2021). These experiences are worse for Latinxs with intersecting identities. Those who identify as Black Latinx, Afro-Latinx, and multiracial Latinx have been the most impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, with significantly higher rates of comorbidity for Black Latinx communities and higher rates of death for Latinxs who identify as multiracial (Poulson et al., Citation2021; Rothe et al., Citation2021). Additionally, undocumented Latinx immigrants have faced language, economic barriers, and unsafe living arrangements during the pandemic. Furthermore, although research shows that COVID-19 has disproportionately affected LGBTQ and Latinx youth, to our knowledge no current systematic review summarizes the findings from the impact of COVID-19 on Latinx LGBTQ communities.

Latinx Heterogeneity and Cultural Values

Latinx people are a culturally rich, yet complex ethnic group often mistaken as racially homogenous (Adames et al., Citation2021). In order to understand specific groups within Latinx communities, such as Latinx LGBTQ youth, one must consider how Latinx-specific cultural characteristics provide unique experiences for different groups. Thus, we briefly discuss important ways in which Latinxs can be racialized and different cultural values that influence ways in which Latinx youth in particular experience the world.

Heterogeneity Among Latinx People

Latinx refers to people who are of Latin American and Caribbean origin or descent and are not limited to only countries that are primarily Spanish (Adames & Chavez-Dueñas, Citation2016). Latinx people descend from more than 30 different countries and territories, with histories pertaining to colonization, migration, phenotypic, and gender expressions, among other differences. In the process of colonization, Latinxs acquired diverse racial identities from the integration of native people, enslaved Africans, and White European colonizers. For example, some identified as Afro-Latinx or Indigenous Latinx. These distinctions are still embraced by Latinx communities today (Chavez-Dueñas et al., Citation2014; Sanchez et al., Citation2019), which places Latinx people in a hierarchy of lighter skinned and White European descent at the top and those of darker skinned and African descent at the bottom. Many Latinxs still report struggling to self-identify racially due to this process termed mestizaje, an ideology that suggests a raceless identity so that colonized groups would be less likely to rebel and challenge such colonization (Chavez-Dueñas et al., Citation2014). Latinx people also hold a wide variety of gender and sexual identities. For example, about 21% of transgender people in the United States identify as Latinx (Hwahng et al., Citation2019). This percentage can also be assumed to be higher for Latinx people who identify as part of the broader LGBTQ community. At the intersection of racism, heterosexism, and cissexism, Latinx LGBTQ people in the United States experience higher rates of minority stress compared to non-Latinx White LGBTQ people, leading to increased negative health outcomes such as depression, anxiety, and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (e.g., Cerezo et al., Citation2021; Estrada et al., Citation2021). Therefore, some specific groups of Latinx people have to navigate prejudice or discrimination based on color of skin, particularly for those with darker skin – colorism (Adames et al., Citation2021; Sanchez et al., Citation2019) along with added layers of oppression such as cissexism and heterosexism.

Latinx people, especially within the United States, also differ in immigrant identity and immigration status (Barrita, Citation2021). Latinxs in the United States have reported consistent persecution because of their immigration status (Barrita, Citation2021; Chavez, Citation2013; Valentín‐cortés et al., Citation2020). With immigration and documentation status comes unique experiences of stress, such as acculturative stress and fear around deportation (e.g., Barrita, Citation2021; Santos et al., Citation2021). The complexity of identities within Latinxs presents unique challenges for these communities, which intensified during the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, there is a need to highlight findings from studies that unpack outcomes found in Latinx LGBTQ youth during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Latinx Cultural Values, Beliefs, and Traditions

Although heterogeneity exists among Latinx people, there are also many shared cultural values, beliefs, and traditions (Adames & Chavez-Dueñas, Citation2016; Delgado-Romero et al., Citation2013). For instance, Latinx cultural values and beliefs about gender norms (e.g., machismo, caballerismo, marianismo) and familismo are particularly important characteristics to understand the intersectional experiences of Latinx LGBTQ youth.

Gender Norms

Gender norms of machismo, caballerismo, and marianismo have guided how Latinx people interact within their families and communities (e.g., Adames & Chavez-Dueñas, Citation2016; Falicov, Citation2014). Machismo highlights the role of males within the family unit as a negative trait, such as being aggressive and rejecting feminine traits (Arciniega et al., Citation2008; Mayo, Citation1997). This gender norm can be challenging for parents when trying to connect with their LGBTQ child (Abreu, Gonzalez, et al., Citation2020; Abreu, Riggle, et al., Citation2020). On the other hand, caballerismo, or Latinx males’ positive traits of emotional connectedness, honor, loyalty, protection, and nurturance (Arciniega et al., Citation2008; Santiago-Rivera et al., Citation2002), may facilitate Latinx parents’ connection and acceptance of their LGBTQ child (Abreu, Gonzalez, et al., Citation2020).

Marianismo, a construct attributed to the role of Latina women within the culture, expects women to be self-sacrificing and put the needs of the family (e.g., husband and children) above their own needs (Delgado-Romero et al., Citation2013; Falicov, Citation2014). Marianismo in Latinx families of LGBTQ youth is an important construct to observe in mother-child dynamics (e.g., Abreu, Riggle, et al., Citation2020). For example, it might be Latinx mothers’ call to be self-sacrificing that allow them to embrace and support their LGBTQ child regardless of other opposing cultural expectations (Abreu, Gonzalez, et al., Citation2020; Abreu, Riggle, et al., Citation2020).

Familismo

Family is a core value that guides interactions between people from collectivistic cultures, such as Latinx people (Adames & Chavez-Dueñas, Citation2016; Arredondo & Tovar-Blank, Citation2014). In Latinx culture, familismo refers to family members’ obligation to prioritize the needs of the collective over their own, acceptance and solidarity with family members, and rely on family for support (Arredondo & Tovar-Blank, Citation2014; Delgado-Romero et al., Citation2013). Research shows that the principle of familismo plays a crucial role in Latinx LGBTQ people’s relationship with their families, and often influences whether they disclose their sexual and gender identity (e.g., Gattamorta & Quidley-Rodriguez, Citation2018; Lozano et al., Citation2021). Similarly, research with family members of Latinx LGBTQ people shows that navigating different family dynamics (e.g., balancing family members’ different reactions about LGBTQ issues) plays a crucial role in whether family members are accepting of their LGBTQ family members (e.g., Abreu, Gonzalez, et al., Citation2020; Abreu, Riggle, et al., Citation2020; Przeworski & Piedra, Citation2020).

Overview of Frameworks

Intersectionality Framework

To better understand the importance of heterogeneity within Latinx LGBTQ communities and how their identities interact with current systems in the United States, we will use the Intersectionality Framework (Crenshaw, Citation1991). Intersectionality originated from the need to highlight the experiences of oppression faced by Black women within the legal system in the United States. Intersectionality proposed that although Black women face discrimination for identities shared with other groups (e.g., White women, Black men), they also experience oppression at the intersection of racism and sexism (Collins, Citation2000; Crenshaw, Citation1989). Conceptualizing the experiences of Latinx LGBTQ youth from an intersectionality framework helps us identify the unique experiences of this group within the COVID-19 pandemic in the face of racism, xenophobia, homophobia, and nativism. For example, we know that Latinx LGBTQ youth experience cissexism and heterosexism from within their Latinx communities as a result of specific cultural beliefs, norms, and traditions such as strict gender norms (e.g., machismo; Abreu, Hernandez et al., Citation2022; Gattamorta et al., Citation2019) and racisms and xenophobia with the larger LGBTQ community. Therefore, it is plausible to believe that the intersection of these oppressive systems within and outside Latinx communities has intensified feelings of isolation and distress during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Minority Stress

To understand the impact of racism, xenophobia, homophobia, and nativism on Latinx LGBTQ communities, we place these within a Minority Stress framework. Minority stress (Brooks, Citation1981; Meyer, Citation2003) proposes that LGBTQ people experience stress on a continuum of distal and proximal stressors. Distal stressors are external events (e.g., violence, microaggressions) that happen to an LGBTQ person, and thus, the person does not have control over these events. For example, Latinx LGBTQ youth experience depression as a result of a lack of acceptance by family members (see review in Abreu et al., Citation2022). Because of these external events, LGBTQ people experience proximal stressors or negative internal perceptions about themselves, such as internalized cissexism and heterosexism (Meyer, Citation2003). For example, LGBTQ youth are more likely to experience shame and guilt about their LGBTQ identity as a result of harassment and repeated messages to conceal their identity (Trevor Project, Citation2021).

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated health disparities for Latinx youth (e.g., Leidman et al., Citation2021). In addition, COVID-19 pandemic has further limited access to mental health services for LGBTQ youth who already experience disproportionate levels of mental health disparities (Chaiton et al., Citation2021; Jones, Bowe et al., Citation2021). From a minority stress framework, it is plausible to believe that as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic Latinx LGBTQ youth are navigating added layers of stress to the already systemic oppressive experiences of racism, xenophobia, cissexism, and homophobia.

Latinx Critical Theory (LatCrit)

Latinx Critical Theory (LatCrit) recognizes that laws and policies in the United States seek to erase Latinx communities by making them invisible in the face of legal and political systems. LatCrit gives voice to the diverse groups that comprise Latinx people and critically interrogate the driving forces behind laws and policies in the United States that intentionally and disproportionally keep Latinx people marginalized (Valdes, Citation2005). Most importantly, LatCrit helps us develop a critical lens of understanding how injustices are embedded within the fabric of the United States and go unchallenged because these are conflated with American’s distorted understanding of truth and justice (Valdes, Citation2005).

Specific to the COVID-19 pandemic, LatCrit provides us a lens from which to conceptualize how multiple layers of oppression embedded in laws and policies may increase health disparities for Latinx LGBTQ youth. For example, undocumented immigrant Latinx families cannot obtain health insurance or work permits (Raymond-Flesch et al., Citation2014) and LGBTQ youth are exposed to daily experiences of minority stress because of cissexism and heterosexism (Brooks, Citation1981; Meyer, Citation2003). Therefore, when looking at these multiple layers of oppression that are sanctioned by existing laws and policies, one can better understand how Latinx LGBTQ youth could potentially have concerning mental health outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Present Study

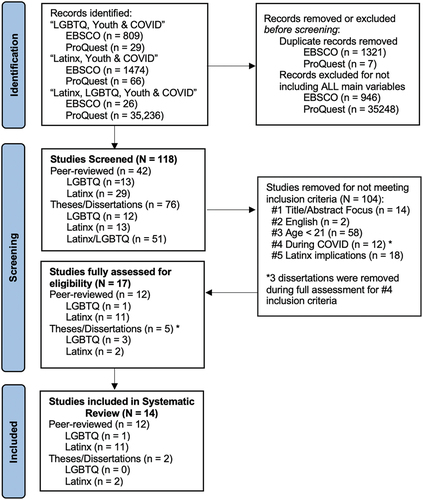

To better understand how the current COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the mental health of Latinx LGBTQ youth, a systematic review was conducted. We utilized the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA; Page et al., Citation2021) guidelines (see ). While there has been extensive research about the role of COVID-19 pandemic on people’s mental health impact (see Serafini et al., Citation2020 for a review), including specific finding for Latinx people (see Moore, Citation2021, for a review), the vast majority of the research addresses adult populations or White cisgender and heterosexual youth and have not assessed for intersecting identities such as Latinx LGBTQ youth. Therefore, in the present systematic review we answered the following research questions:

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram of identification, screening, and inclusion process for systematic review.

What challenges and stressors have Latinx LGBTQ youth faced during the COVID-19 pandemic?

What mental health impact has the COVID-19 pandemic had on Latinx LGBTQ youth?

Methods

Search Strategy

This paper used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement method (Page et al., Citation2021) and the updated PRISMA checklist (Page et al., Citation2021) to conduct a systematic literature review about the challenges and stressors and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of Latinx LGBTQ youth. The PRISMA checklist provides a clear and efficient process for conducting a systematic review that has been effectively used in recent reviews to cover the mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic (Jones, Mitra et al., Citation2021).

In the current study, we utilized the EBSCO host system to search across 60 databases related to health and social sciences, which included sources such as PsychINFO, LGBTQ+ Source, and Wilson Web (see supplementary Appendix A for the entire list). Additionally, given the underrepresentation of Latinx LGBTQ people in research compared to other racial and ethnic groups, we used ProQuest database to find theses or dissertations that might also fit our search criteria. We used different combinations of keywords (see supplementary Appendix B), including synonyms for the four main key terms of focus in our review: (1) Latinx (e.g., Latina, Latino, Latine, Hispanic, Mexican, Chicano/a), (2) LGBTQ (e.g., sexual minority, gender minority, LGB, gay, lesbian, bisexual, queer, transgender), (3) youth (e.g., children, minors, adolescents, underage, teenagers), and (4) COVID-19 (i.e., pandemic, SARS-Co-V2, Coronavirus). The search was conducted in early October 2022.

The COVID-19 pandemic, connected to the SARS-CoV-2 virus, was first reported globally in 2019 by the World Health Organization (WHO). Thus, we limited our search to peer-reviewed articles and theses and dissertations published from 2019 to October 2022 when the search was conducted. Initial intersectional efforts to exclusively use studies focusing on LGBTQ Latinx youth showed limited results. Thus, we expanded our criteria and considered studies that focused on the mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on either LGBTQ youth and/or Latinx youth.

Search Results, Eligibility, and Inclusion Criteria

An initial search in EBSCOhost produced 1474 articles for combinations of the keywords (and their synonyms) Latinx, youth, and COVID-19. The combinations of keywords and synonyms for LGBTQ, youth, and COVID-19 produced 809 articles. Finally, when we combined all four keywords (and their synonyms) Latinx, LGBTQ, youth, and COVID-19, we found 26 articles. Overall, 2309 peer-review publications were drawn for consideration. Compared to EBSCOhost, ProQuest database had more limitations about using advanced searches. We were forced to combine all four main keywords Latinx, LGBTQ, youth, and COVID-19 to draw the closest articles related to our focus. Our search pulled over 35,000 published theses and dissertations, which was much larger than our peer-reviewed paper search in EBSCOhost. This was partially because this database has less controls to filter papers. Given the extensive number of theses and dissertations we found, two of the authors briefly reviewed titles and abstracts for the first 500 papers for possible inclusion. ProQuest search engine finds, and filters papers based on relevance to the keywords. During the first 200 papers we reviewed, 76 were identified to be relevant to all keywords. However, once we reviewed past 500 papers, we couldn’t find any other relevant papers for our review and concluded that the remaining of the papers were only relevant to one of the keywords and not all four. Thus, we stopped screening the remaining papers pulled by this search. After removing duplicates, the initial pre-screening process pulled 42 peer-reviewed publications and 76 theses and dissertations, for a total of 118 papers for initial consideration.

Three of the authors used the following inclusion criteria to screen all 118 papers: (1) the title or abstract indicated a main focus on the mental health impact of COVID-19 using a sample of LGBTQ youth, Latinx youth, or LGBTQ Latinx youth, (2) the article was written in English, (3) sample used was youth 20 years old or younger, (4) the article focused on empirical research (e.g., quantitative research, qualitative research, mixed methods) that explicitly stated that was conducted on or during the COVID-19 pandemic (from late 2019 forward), (5) for LGBTQ youth studies, findings described implications for Latinx youth. The first four authors independently engaged in a search using the agreed-up inclusion criteria and met weekly as a team to confirm results. Discrepancies were discussed until collective agreement was reached.

After excluding articles that did not meet our first inclusion criteria, a total of 104 papers were left. Next, using our second criteria, two articles written in Spanish were removed. Using our third inclusion criteria, 58 papers were excluded for using samples of participants who were older than 20 years old. Next, 12 papers were removed because they did not include a sample collected during the COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, 18 LGBTQ-focused papers were removed because their results did not provide any specific implications for Latinx participants, or their sample did not include Latinx participants at all. After completing our search, 17 papers (12 peer-reviewed publications and five theses or dissertations) comprised the final sample (see for full PRISMA inclusion process). To ensure every possible qualifying paper was considered, once we completed the inclusion criteria, we conducted a final backward and forward search (White et al., Citation2009) on all 17 papers. However, no additional papers met criteria. Once our full search was completed, the first four authors read and reviewed all 17 papers. Through this process, we realized three papers (all dissertations; Courtwright, Citation2022; Richter, Citation2022; Tovar, Citation2022) did not fully met our criteria because they did not collect their data during the COVID-19 pandemic (inclusion #4) or did not provide specific findings for Latinx people (inclusion #5), and, therefore, were excluded from further review. Finally, a total of 14 papers were included in this systematic review (see supplementary Table 1 for a summary of each study).

Data Extraction, Review, and Risk of Biases

The final 14 studies were categorized and extracted by research topic, research method, demographic information (e.g., sample size, gender, age), and sampling procedures (see supplementary Table 1). Additionally, each study was reviewed by two researchers for common patterns across studies in terms of: (1) factors related to being Latinx, (2) factors related to being a sexual or gender minority, and (3) mental health impact and barriers connected to the COVID-19 pandemic. We present these findings as part of our results and discussion.

To assess risk of bias in the reviewed studies, we utilized the CADIMA (Kohl et al., Citation2018) appraisal system, which has been previously used in similar systematic reviews (see Jones, Mitra et al., Citation2021). The standards for critical appraisal and rating system were defined as follow: (a) study design is clearly reported (e.g., cross-sectional, experimental, longitudinal) = 1, otherwise = 0; (b) large sample size = 1, small = 0; (c) measures were reported and have been previously validated = 1, novel or not validated measures = 0; and (d) recruitment of participants was done at random or lack of bias = 1, convenience or nonrandom sample = 0. Each article was appraised for risk of bias by two researchers independently who scored each article using a range of 0 to 4, where higher scores represented less risk of biases for each study. An average of the scores appraised by two of the authors is presented in supplementary Table 2.

Results

Of the fourteen articles that comprised our final sample, eleven of them focused on Latinx youth (Cavey, Citation2021; Cortés-García et al., Citation2022; D’Costa et al., Citation2021; Gaxiola Romero et al., Citation2022; Kellogg, Citation2022; Martinez et al., Citation2022; Penner et al., Citation2021; Roche et al., Citation2022; Sun et al., Citation2021; Trucco et al., Citation2022; Valdez-Santiago et al., Citation2022), one focused on youth broadly (Velez et al., Citation2022), one focused on LGBTQ youth (Platero & López-Sáez, Citation2022), and one focused on Youth of Color (Tao & Fisher, Citation2022). Five patterns relevant to the aim of this review emerged: (1) impact of school closure, (2) pandemic stressors, (3) online media, (4) family and Latinx cultural values, and (5) interventions. It is important to note that we found only one study that specifically focused on the intersection of LGBTQ and Hispanic (not Latinx) youth (Platero & López-Sáez, Citation2020). Before presenting each pattern, we provide an overview of the design, sample, and characteristics of the fifteen studies we found.

Studies and Participants’ Demographics

The included studies in this literature review were conducted in the United States (n = 11), Mexico (n = 2), and Spain (n = 1). The majority of studies utilized quantitative methods (n = 8), with four studies utilizing qualitative methods, and two studies using mixed methods. Eight of the studies were longitudinal (Cavey, Citation2021; Gaxiola Romero et al., Citation2022; Kellogg, Citation2022; Penner et al., Citation2021; Roche et al., Citation2022; Sun et al., Citation2021; Trucco et al., Citation2022; Valdez-Santiago et al., Citation2022), while the other six were cross-sectional (Cortés-García et al., Citation2022; D’Costa et al., Citation2021; Martinez et al., Citation2022; Platero & López-Sáez, Citation2022; Tao & Fisher, Citation2022; Velez et al., Citation2022). Within the eleven studies that centered Latinx and/or Hispanic youth, eight exclusively looked at Latinx and/or Hispanic youth (Cavey, Citation2021; D’Costa et al., Citation2021; Gaxiola Romero et al., Citation2022; Kellogg, Citation2022; Martinez et al., Citation2022; Roche et al., Citation2022; Sun et al., Citation2021; Valdez-Santiago et al., Citation2022) and three had participant samples that were predominantly Latinx and/or Hispanic youth (Cortés-García et al., Citation2022; Penner et al., Citation2021; Trucco et al., Citation2022). The eight studies that exclusively recruited Latinx and/or Hispanic youth included a total of 24,261 participants and did not include information on sexual identity. The three studies that had predominantly Latinx and/or Hispanic samples had a total of 506 participants, including 385 Latinx or Hispanic participants, and did not include information on sexual identity. The two studies that looked at youth broadly included a total of 8,565 participants, including 1,344 Latinx or Hispanic participants. The one study that centered LGBTQ youth included a total of 445 participants from Spain. The one study that centered Youth of Color included a total of 407 participants, including 101 Latinx participants.

Regarding gender, most studies except for three (Sun et al., Citation2021; Trucco et al., Citation2022; Velez et al., Citation2022) included slightly more women (range 51% to 80%) than men. Most participants were cisgender (range 68.6% to 96%) compared to transgender and/or gender diverse participants, or a distinction between cisgender and transgender was not reported. Only two studies (Platero & López-Sáez, Citation2022; Tao & Fisher, Citation2022) reported sexual identity information with one study (Tao & Fisher, Citation2022) collecting information on whether the youth identified broadly as a gender or sexual minority (4.67%) and for the other study (Platero & López-Sáez, Citation2022) bisexual participants (58.4%) made up the largest category. Furthermore, only one study (D’Costa et al., Citation2021) assessed for ethnicity and race as two different categories, with approximately 45% of the participants identifying as “Latinx” only, approximately 15% as white-Latinx, and approximately 1% as Filipino-Latinx, and less than 1% as Asian-Latinx.

Impact of School Closure

Five of the studies (Cavey, Citation2021; Cortés-García et al., Citation2022; Platero & López-Sáez, Citation2022; Valdez-Santiago et al., Citation2022; Velez et al., Citation2022) emphasized the different impacts that the closing of schools and stay-at-home mandates had on Latinx youth during the pandemic. Latinx youth reported that they experienced heightened social disconnection and disruption such as not being able to spend time with friends, disrupted daily routines, and missing out on key experiences (e.g., homecoming, prom; Platero & López-Sáez, Citation2022; Velez et al., Citation2022). Because interactions with friends, family, and teachers were forced to move from face-to-face to online, participants described that the limitations and inadequacy of online interactions provided them limited social connections and support (Velez et al., Citation2022). Additionally, Latinx youth expressed that the transition to online school negatively impacted their learning such as not being able to contact teachers as easily and not feeling prepared for future years (Cortés-García et al., Citation2022).

Furthermore, being at home posed academic challenges (e.g., impact on grades, difficulties turning in schoolwork) for Latinx youth due to distractions present in the home, especially siblings and sibling care, and poor internet connection (Cortés-García et al., Citation2022; Velez et al., Citation2022). Latinx youth also expressed difficulties coping with increased stress due to changes in academic delivery such as concerns about missing out on preparation or readiness for future years in high school or college (e.g., college application help, touring campuses; Velez et al., Citation2022). For LGBTQ+ Hispanic youth, being stuck at home has increased behavior monitoring from potentially unsupportive family/house members resulting in increased experiences of violence within the home (Platero & López-Sáez, Citation2022). Combined with the loss of support networks (e.g., physical contact or spaces with friends and/or chosen family), LGBTQ+ Hispanic youth experienced increased discomfort within the home (Platero & López-Sáez, Citation2022). In addition, Platero and López-Sáez (Citation2022) found that trans and gender diverse youth and younger LGBTQ+ youth (ages 13–17) were exposed to more violence from unsupportive family members during stay-at-home mandates. Overall, increased academic challenges, social disruption/isolation, discomfort, and violence within the home all translated to higher experiences of negative mental health outcomes such as anxiety, stress, and depression for Latinx youth (e.g., Cortés-García et al., Citation2022; Platero & López-Sáez, Citation2022; Valdez-Santiago et al., Citation2022; Velez et al., Citation2022).

Latinx youth also expressed some positive aspects of moving to remote online schooling as a result of school closures (Cavey, Citation2021). For example, Latinx youth reported that not having to go to school in person allowed them to balance the different areas of their lives better and distance themselves from certain stressors of in-person school such as bullying and social cliques (Cavey, Citation2021). In addition, attending classes online after physical schools closed was found to be a protective factor of mental health and reduced the likelihood of suicide attempts (Valdez-Santiago et al., Citation2022). These benefits allowed Latinx youth to gain more confidence, improve their mental health, and shape more positive self-concepts and future orientations (Cavey, Citation2021). It is important to note that access to the internet, computers, and other home amenities conducive to learning are not universally available, causing youth to drop out from school within six months of the pandemic in places like Mexico (Statista, Citation2021).

Pandemic Stressors

Six studies found that several different stressors experienced by Latinx youth during the pandemic heightened experiences of negative mental health concerns and stress, including: (1) economic challenges, (2) adverse childhood experiences, and (3) racism.

Economic Challenges

Four studies discussed economic stressors Latinx youth faced during the pandemic (Cortés-García et al., Citation2022; Roche et al., Citation2022; Valdez-Santiago et al., Citation2022; Velez et al., Citation2022). Latinx youth disproportionately reported that the pandemic presented job-related challenges for their families (e.g., Cortés-García et al., Citation2022; Roche et al., Citation2022; Velez et al., Citation2022). For example, almost one-fifth of the participants in Roche et al. (Citation2022) study reported that their household was experiencing both job loss and reduced work hours, leading to increased family financial problems due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Along with family members losing jobs and/or dealing with a reduced income, Latinx youth disclosed other family members have had to work more hours or rely on food banks, churches, or savings in order to meet the family’s basic needs (Cortés-García et al., Citation2022). These economic impacts of COVID-19 resulted in increased experiences of stress for Latinx youth (e.g., Roche et al., Citation2022; Velez et al., Citation2022). Valdez-Santiago et al. (Citation2022) also found that socioeconomic level was negatively associated with suicide attempts, with participants at the lowest socioeconomic level presenting with the highest prevalence of suicide attempts compared to those at higher or highest socioeconomic levels.

Adverse Childhood Experiences

One study, D’Costa et al. (Citation2021), explored the impact that adverse childhood experiences (ACE) has had on Latinx youth’s experiences of pandemic stress. This study found that youth’s previously experienced ACEs, resilience, and pandemic exposure were all connected to their experiences of pandemic stress. Additionally, participants who identified as women/female experienced disproportionate higher levels of pandemic related stress and mental health impacts compared to their men/male identified counterparts (D’Costa et al., Citation2021).

Racism

Two studies (Cortés-García et al., Citation2022; Tao & Fisher, Citation2022) discussed the ways in which racism may be impacting Latinx youth. One study found that while younger Latinx youth were not necessarily aware of experiences of racial disparities during the pandemic, older Latinx youth were more aware of these structural disparities and the ways in which COVID-19 has disproportionately impacted racially and ethnically marginalized communities such as experiences navigating the healthcare system (Cortés-García et al., Citation2022). Additionally, Tao and Fisher (Citation2022) found that stay-at-home mandates coupled with increased racial social justice movements during the first year of the pandemic may have increased Youth of Color, including Latinx youth, exposure to media racism, as well as the use of social media and online as a form of civic engagement (i.e., racial justice activity coordination and racial justice civic publication on social media; Tao & Fisher, Citation2022). For example, Tao and Fisher (Citation2022) found that hours spent on social media and engagement in racial justice activity coordination were positively associated with exposure to individual racial discrimination on social media, and racial justice civic publication (e.g., posting links or personal stories on social media related to racial issues) was positively associated with vicarious racial discrimination on social media. Both types of social media racial discrimination, vicarious and individual, were significantly associated with depressive symptoms, anxiety, and substance use (e.g., alcohol use disorder; Tao & Fisher, Citation2022).

Online Media

As previously mentioned, online media use and consumption is likely to have increased following stay-at-home mandates and school closures. Three studies (Cortés-García et al., Citation2022; Tao & Fisher, Citation2022; Trucco et al., Citation2022) explored the impact of online media on Latinx youth. For example, as explained above, Youth of Color who spend more time on social media experienced higher rates of racial discrimination, which impacted their mental health and well-being (e.g., depressive symptoms, anxiety, and substance use; Tao & Fisher, Citation2022). One study also looked at exposure to COVID-19 related media coverage and its impact on youth’s well-being (Trucco et al., Citation2022). Trucco et al. (Citation2022) found that greater exposure to COVID-19 related media coverage predicted greater engagement in COVID-19 safety behaviors such as hygiene-related behaviors (e.g., handwashing) and social distancing. This increase in COVID-19 safety behaviors was associated with a greater negative impact on the youth’s quality of life and mental health (e.g., depressive and anxiety symptoms, stress, and compulsions/obsessions over hygiene; Trucco et al., Citation2022). Additionally, Latinx youth reported feeling overwhelmed, sadness, worry, and stress due to media coverage of COVID-19 (Cortés-García et al., Citation2022). Finally, some youth reported engaging in avoidance behaviors (e.g., avoiding listening to the news) to cope with the negative impacts of media coverage of the virus (Cortés-García et al., Citation2022).

Role of Latinx Family and Other Cultural Values

As described above, while Latinx youth experienced heightened challenges and negative impacts due to the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., increased academic challenges and negative mental health outcomes), some studies suggest that Latinx cultural values might have buffered and lessened the impact of COVID-19 pandemic stressors and varying outcomes for Latinx youth. Specifically, five studies (Cortés-García et al., Citation2022; D’Costa et al., Citation2021; Gaxiola Romero et al., Citation2022; Penner et al., Citation2021; Sun et al., Citation2021) reported on how the cultural values of familismo and collectivism might have provided Latinx youth a source of resilience and protection against increased pandemic stress and other negative mental health outcomes. For example, Penner et al. (Citation2021) found that better family functioning resulted in decreased mental health symptoms for Latinx youth. Latinx youth also shared the support community members offered each other helped with pandemic related stress (Cortés-García et al., Citation2022). D’Costa et al. (Citation2021) found that Latinx youth did not have significantly higher levels of pandemic stress than White non-Latinx youth and proposed that one reason for this could be the increased time spent with immediate and extended family due to stay-at-home mandates. Similarly, another study found that a positive family environment resulted in decreased general stress, increased academic engagement, and well-being of Latinx youth during the pandemic (Gaxiola Romero et al., Citation2022). Some Latinx youth reported that in spite of all pandemic related difficulties, they were grateful for the ability to spend more time with family and have their support throughout the pandemic (Cortés-García et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, Sun et al. (Citation2021) found that school closure had a positive impact on sibling positivity for Latinx siblings with a higher connection to Latinx cultural values, specifically familismo.

Two studies found that Latinx youths increased responsibilities around the house or in childcare for their siblings had negative impacts on their mental health and academic performance (Cortés-García et al., Citation2022; Roche et al., Citation2022). Household jobs, income loss, family member’s hospitalizations, and parent workload resulted in increased adolescent childcare responsibilities. As a result of these increased responsibilities within their family, Latinx youth school performance was negatively impacted, as well as leading to feelings of being overwhelmed, increased anxious, depressive, somatic symptoms, and engagement in rule-breaking and aggressive behaviors (Cortés-García et al., Citation2022; Roche et al., Citation2022). It is important to note that due to traditional gender roles and expectations for boys/men vs. girls/women within Latinx culture, the negative consequences for sibling care for Latinx youth had a more profound effect for Latina adolescent girls (Roche et al., Citation2022). Additionally, one study (Velez et al., Citation2022) suggested that the importance placed on education within Latinx culture may be the reason that Latinx youth uniquely reported increased academic challenges and subsequent stress compared to other non-Latinx youth. Finally, family conversations about COVID-19 led to increased social distancing fears and increased negative mental health outcomes (e.g., stress, depressive and anxiety symptoms; Trucco et al., Citation2022).

Interventions

Two studies (Kellogg, Citation2022; Martinez et al., Citation2022) focused on implementing and evaluating interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic and the impacts the results of the interventions could have on future responses or interventions. Martinez et al. (Citation2022) examined the impact of moving a school-based group prevention program for eliminating mental health disparities within the new Latinx immigrant youth community to telehealth. Results showed three positive and negative aspects of this intervention. That is, the telehealth modifications allowed for more accessibility, creativity, sharing, flexibility in communication, and increased comfortability (e.g., being able to turn off their camera to allow them to slowly become more comfortable), allowing participants to establish and maintain a sense of social connectedness despite stay-at-home mandates. However, participants had to deal with unstable internet connection, technical difficulties, less organic facilitation, more discomfort in engaging in some activities, and difficulties finding private spaces to speak freely. In addition, Kellogg (Citation2022) developed and implemented an educational health-promotion intervention program for Latinx youth in an effort to mitigate exacerbated health inequities due to the COVID-19 pandemic and to promote Latinx youth’s physical, emotional, mental, social, and community health. This study found that this program, and potentially other culturally responsive curricula, were successful in addressing the exacerbated health challenges that Latinx youth are facing due to COVID-19. Also, collaboratively developing and implementing interventions in real time during public health emergencies can be effective in supporting marginalized groups, and can provide opportunities for growth and development by listening to the needs of communities (Kellogg, Citation2022).

Discussion

Our systematic review uncovered 14 articles that explored the challenges, stressors, and impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Latinx LGBTQ youth. Our findings suggest that while there has been some research on the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on racial, ethnic, sexual and/or gender minority youth, most of this research has only used samples based on one form of marginalization (e.g., racism, cissexism), often failing to include intersectional approaches. For instance, we found only one study that had a sample of Hispanic (but not Latinx) LGBTQ youth populations (Platero & López-Sáez, Citation2022). Therefore, research during the COVID-19 pandemic focusing on Latinx or LGBTQ youth has neglected addressing the intersection of racial, ethnic, sexual and/or gender minority identities for Latinx LGBTQ youth. Patterns across our systematic review show that during the COVID-19 pandemic, Latinx and/or Hispanic youth have been impacted from school closures, pandemic stressors, and online media. In addition, some studies evaluated the effectiveness of interventions with Latinx youth aimed at mitigating the effects of COVID-19 on Latinx youth’s health, including a telehealth program. Furthermore, family and Latinx cultural values emerged as a source of support and stress for this population.

Our review suggests that Latinx youths are experiencing new and increased stressors and challenges (e.g., transitioning to online school, exposure to racism online, economic stressors, hygiene-related fears). These different challenges have impacted Latinx youth’s mental health, including increased experiences of depression, anxiety, and stress, among other outcomes. Our review also found that online interventions came with both positive and negative impacts on the effectiveness and that a culturally-responsive curriculum might effectively address the COVID-19-exacerbated health challenges for Latinx youth. Furthermore, our review also suggests that the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the wellness of this population may be buffered by Latinx cultural values such as familismo. That is, increased time spent with immediate and extended family members due to stay-at-home mandates may have buffered the harmful effects of the pandemic on this community. However, living circumstances with family were reported differently by LGBTQ Hispanic youth. Specifically, while most Latinx youths reported family as a buffer to pandemic-related stressors, LGBTQ Hispanic youth reported family lack of support was an additional stressor. LGBTQ Hispanic youth during the pandemic struggled with moving back to unsupportive spaces where they were not free to express their identity(ies) fully.

Suggestions and Recommendations When Considering Latinx LGBTQ Youth

Based on our systemic review’s findings, we highlight important implications and connect them with previous recommendations for sexual and gender minority youth. Latinx LGBTQ youth lack support as they navigate different systems of oppression. It is often the case that these communities struggle to feel affirmed and welcomed. Latinx LGBTQ youth experience racism and xenophobia within the LGBTQ community (e.g., Zongrone et al., Citation2020) and homophobia, biphobia, and transphobia within Latinx spaces (see review in Abreu et al., Citation2022; Abreu, Hernandez et al., Citation2022). As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to impact marginalized groups, including Latinx LGBTQ youth, clinicians must be prepared to serve these communities. Specific for Latinx LGBTQ youth, clinicians should ground their interventions on theory- and evidence-based recommendations that best capture the intersecting identities of these communities.

Our findings indicated that during the COVID-19 pandemic most of the research on Latinx youth did not address other forms of marginalization such as sexual and gender identity, limiting our knowledge on how the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted Latinx LGBTQ youth. However, our systematic review found important implications for Latinx youth that can be connected with LGBTQ youth using previous experts’ recommendations. We draw suggestions based on our results for LGBTQ Latinx youth and connect them with Fish’s (Citation2020) recommendations for conducting LGBTQ youth research.

Framing a Life Course Perspective for Latinx LGBTQ Health During and After the Pandemic

Scholars have argued that methodology that addresses systems of oppression must consider approaches that can assess the direction and change of these factors (Fish, Citation2020). Specifically, because the literature about the oppression of marginalized groups such as Latinx LGBTQ often uses cross-sectional approaches, we are limited in the knowledge about the implications for these communities. Our systematic review found that in a critical period such as the COVID-19 pandemic, only eight studies considered longitudinal approaches that framed a time or part of a life course for Latinx youth health. Particularly at early stages of development, such as childhood and adolescence, longitudinal approaches could highlight specific changes over time around socialization and racialization for groups with multiple marginalized identities, such as Latinx LGBTQ (Fish, Citation2020). Similarly, implementing intervention studies in critical times could help expand our understanding of how marginalized communities are affected over time. Our review identified two studies (Kellogg, Citation2022; Martinez et al., Citation2022) that explored the experiences of Latinx youth during the COVID-19 pandemic. Future research should consider using a methodology that can capture change over time as Latinx LGBTQ youth experience disparities during a pandemic or another significant world event. Similarly, clinicians and providers should consider assessing the history and development of mental health symptoms during a pandemic for Latinx LGBTQ youth.

Expand Notions of Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Compared to their White non-Latinx counterparts, Latinx people have been overly represented in COVID-19 cases in the United States, including hospitalization and deaths (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], Citation2022). In fact, since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Latinx community has experienced consistently high rates of COVID-19 infections and negative mental health outcomes (CDC, Citation2022). Researchers have argued that these disparities are attributed to structural factors such as racism, lack of access to hospital resources, and inability to take off work, among others (e.g., Cortés-García et al., Citation2022; Huang et al., Citation2022; Jacobson et al., Citation2021). From an intersectionality and LatCrit perspective, we can see how Latinx families are navigating multiple systems of oppression to, quite literally, survive and keep their families safe during the COVID-19 pandemic. This includes how parental figures and other family members interact with Latinx LGBTQ youth.

Our systematic review of studies assessing the impact of Latinx LGBTQ youth during the pandemic found that their mental health was impacted in various ways. Fish (Citation2020) suggests that for minoritized groups such as LGBTQ youth, it is important to consider how mental health and positive youth development can be measured and assessed outside of traditional stress, anxiety, and depression measures. LGBTQ youth can also be developmentally impacted by social factors such as academic engagement, family support, or negative coping mechanisms (e.g., substance use). Our systematic review suggested similar social influences for Latinx youth. Valdez-Santiago et al. (Citation2022) found that changes in education from in-person to virtual settings became a protective factor against racial discrimination for Latinx youth in supportive family environments.

Similarly, various studies found that economic inequity and economic instability due to parent’s loss of income during the pandemic, as the main predictor of emotional stress among Latinx youth (Cortés-García et al., Citation2022; Roche et al., Citation2022; Valdez-Santiago et al., Citation2022; Velez et al., Citation2022). These findings among Latinx youth mirror Fish’s (Citation2020) suggestion to expand our understanding of mental health for LGBTQ youth, and specifically given that the intersection among Latinx LGBTQ youth heavily depends on social factors outside their control. Future research and practice with Latinx LGBTQ youth should continue to consider multiple factors that help explain the psychological impact on these communities.

Consider That Experiences for Latinx and LGBTQ Youth are Multifaceted

Clinicians can provide a safe space where Latinx LGBTQ youth can name and process how the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted them. In doing so, clinicians should acknowledge the cultural dissonance, or heightened confusion and conflict because of one’s environment, that they may be experiencing due to being forced to be in spaces where their authentic self is not affirmed. Fish (Citation2020) suggests that providers among sexual and gender minority youth, must consider how these communities’ experiences are contextual and multifaceted, particularly when addressing health disparities. Similarly, clinicians can provide a safe space to discuss the negative mental outcomes of having to conceal one’s LGBTQ identity to honor specific Latinx cultural expectations or endure racism and xenophobia from being in predominantly White LGBTQ spaces. When appropriate, clinicians engage in a dialogue about how minority stress, intersectionality, and existing policies contribute to Latinx LGBTQ people’s negative mental health to empower and create critical consciousness among these communities (see a review of critical consciousness in Cadenas & McWhirter, Citation2022).

Similarly, supportive or unsupportive systems at home should be considered. For instance, family support is crucial for the well-being of Latinx (see review in Cahill et al., Citation2021) and LGBTQ youth (e.g., Bouris et al., Citation2010). Specifically for Latinx LGBTQ youth, family support is instrumental in their mental health outcomes such as depression (Abreu et al., Citation2022; Abreu, Lefevor et al., Citation2022). As described in this paper, family support seems to buffer the negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on young people’s mental health. Specific to Latinx LGBTQ youth, families seem to be a source of distress during the COVID-19 pandemic (Platero & López-Sáez, Citation2022). However, Latinx family members of LGBTQ youth are using Latinx cultural values, including familismo, to support and build relations with their LGBTQ family members (e.g., Abreu, Gonzalez, et al., Citation2020; Abreu, Riggle, et al., Citation2020; Gattamorta et al., Citation2019). Latinx LGBTQ youth report a strong connection to their family regardless of their approval of their sexual identity (e.g., Muñoz-laboy et al., Citation2009). Therefore, culturally appropriate interventions allow clinicians to work with Latinx family members through layers of stress experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic and create an affirming and supportive environment for Latinx LGBTQ youth. Heterogeneity and Mental Health among Latinx LGBTQ Youth

Clinicians should be aware that the COVID-19 pandemic affects all Latinx LGBTQ youth differently and, thus, should design interventions that address their clients’ specific needs. For example, increased anti-immigrant rhetoric and violence toward undocumented people directly affect undocumented Latinx people’s mental health (Barrita, Citation2021; Ro et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, research shows that Latinx transgender youth experience less support from family members than their Latinx cisgender counterparts (e.g., Abreu et al., Citation2022). The finding in our review suggested that experiences of racism were salient for Latinx youth (Cortés-García et al., Citation2022; Tao & Fisher, Citation2022) during the pandemic. Nevertheless, further research is needed to unpack nuance and differences when experiencing racism among Latinx youth, particularly for Afro-Latinx, Indigenous Latinx, and undocumented Latinx people (Sanchez et al., Citation2019). Similarly, among LGBTQ-related oppression and experiences, Platero and López-Sáez (Citation2022) found differences in levels of violence reported by transgender participants compared to their cisgender counterparts in a sample of Hispanic youth. This heterogeneity must continue to be considered and addressed in research with Latinx LGBTQ youth.

Clinicians should avoid conceptualizing the experiences of Latinx LGBTQ people as a monolith and create interventions that specifically address different layers of privilege and oppression. For example, interventions that might help address symptoms of depression due to the COVID-19 pandemic for a documented White, Latinx, cisgender, and gay man might not prove effective for an undocumented, Black Latinx, transgender, young woman without examination of xenophobia, racism and colorism, and cissexism.

Community Context and Resources for Latinx LGBTQ Youth

Community resources are essential for minoritized groups such as LGBTQ youth (Fish, Citation2020). Research on LGBTQ people, including racial and ethnic minorities, shows that connecting with similar minoritized communities has been a source of resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., Abreu et al., Citation2021; Barrita, Citation2021; Riggle et al., Citation2021). In fact, because LGBTQ people have been skeptical of the government’s ability to protect them, they have turned to those within the LGBTQ community for support during the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., forming online support groups, scheduling weekly calls to check on each other’s mental health; Abreu et al., Citation2021; Gonzalez et al., Citation2021). In our systematic review, community resources influenced how Latinx youth experienced the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, Latinx youth lost some of their support systems when they moved to online school due to the COVID-19 pandemic and reported experiencing discrimination in social media platforms (Cortés-García et al., Citation2022; Tao & Fisher, Citation2022; Trucco et al., Citation2022). Clinicians can be instrumental in connecting Latinx LGBTQ youth with supportive groups (both in person and online) that could provide a sense of a community belonging. For example, directing Latinx LGBTQ youth to safe online spaces where they can form community and cultivate resilience might be crucial in improving their mental health. Building a community could be particularly helpful for Latinx LGBTQ youth who find themselves back home with unsupportive family members whose mental health is affected.

Given the extensive research on the importance of family among Latinx people, we assert that Latinx families have the resources necessary to build strong connections. Specifically, in working with Latinx family members and Latinx LGBTQ youth, we pose that existing family-based culturally sensitive interventions could be used to address the relationship between Latinx LGBTQ youth and their family members during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our systematic review included two studies (Kellogg, Citation2022; Martinez et al., Citation2022) that use interventions among Latinx youth to reduce the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. We pose that this intervention can be adapted to include specific information about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on LGBTQ youth broadly and current research about the lack of support from family members for Latinx LGBTQ people. During sessions with Latinx family members where the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on Latinx LGBTQ youth are discussed, clinicians can encourage Latinx family members to journal about any reactions and feelings that might come up for them. Previous research with Latinx family members of LGBTQ people has shown that expressive writing as an intervention creates foundational understandings of emotions experienced by Latinx family members struggling to support their LGBTQ family members (Abreu, Riggle, et al., Citation2020).

Limitations

Our systematic review presents important limitations. First, although we did not set parameters around geographical location, allowing for the possible inclusion of studies conducted outside of the United States, we did limit inclusion to only studies written in English. While our search only excluded two studies in Spanish, it is likely that a bilingual or Spanish search and review might find additional and important implications about Latinx LGBTQ youth experiences during the pandemic. Second, while our search criteria used several synonyms of the main keywords for our search, it is possible that other studies using alternative keywords that were not considered in this study might still connect to experiences of Latinx LGBTQ youth. Third, our search in ProQuest for theses and dissertations was limited to the first 500 most relevant studies, after continuously not finding possible matches for our focus. That said, it is possible that additional studies were not considered in our review. Fourth, our searches found several papers that assessed psychological impact for Latinx and/or LGBTQ people that included youth (21 years or younger) but that did not specifically explore differences in experiences for children or adolescents’ subsamples or did not disclose comparative analyses’ results, making it difficult to include them in our systematic review. Future research addressing psychological implications for marginalized groups, such as Latinx LGBTQ youth should consider assessing any within-group differences based on developmental stages (e.g., children vs. adolescents) when using samples that age-wise belong to two different developmental periods. Finally, the interpretation of our findings should be conservatively considered for Latinx LGBTQ+ youth, given the limited findings available in the literature. More importantly, future researchers should consider unpacking within groups differences among both Latinx and LGBTQ+ communities.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (89.9 KB)Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental material for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2022.2158839.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

This article is part of the special issue “Understanding the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of Latinx Children, Youth, and Families: Clinical Challenges and Opportunities” edited by José M. Causadias and Enrique W. Neblett, Jr.

References

- Abreu, R. L., Gonzalez, K. A., Arora, S., Sostre, J. P., Lockett, G. M., & Mosley, D. V. (2021). “Coming together after tragedy reaffirms the strong sense of community and pride we have:” LGBTQ people find strength in community and cultural values during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. Online First. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000516

- Abreu, R. L., Gonzalez, K. A., Rosario, C. C., Pulice-Farrow, L., & Rodríguez, M. M. D. (2020). “Latinos have a stronger attachment to the family”: Latinx fathers’ acceptance of their sexual minority children. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 16(2), 192–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2019.1672232

- Abreu, R. L., Hernandez, M., Ramos, I., Badio, K. S., & Gonzalez, K. A. (2022). Latinx Bi+/Plurisexual Individuals’ Disclosure of Sexual Orientation to Family and the Role of Latinx Cultural Values, Beliefs, and Traditions. Journal of Bisexuality. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299716.2022.2116516

- Abreu, R. L., Lefevor, G. T., Gonzalez, K. A., Barrita, A. M., & Watson, R. J. (2022). Bullying, depression, and parental acceptance in a sample of Latinx sexual and gender minority youth. Online First. Journal of LGBT Youth, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2022.2071791

- Abreu, R. L., Riggle, E. D., & Rostosky, S. S. (2020). Expressive writing intervention with Cuban-American and Puerto Rican parents of LGBTQ individuals. The Counseling Psychologist, 48(1), 106–134. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000019853240

- Adames, H. Y., & Chavez-Dueñas, N. Y. (2016). Cultural foundations and interventions in Latino/a mental health: History, theory and within group differences. Routledge.

- Adames, H. Y., Chavez-Dueñas, N. Y., & Jernigan, M. M. (2021). The fallacy of a raceless Latinidad: Action guidelines for centering Blackness in Latinx psychology. Journal of Latinx Psychology, 9(1), 26–44. https://doi.org/10.1037/lat0000179

- Arciniega, G. M., Anderson, T. C., Tovar-Blank, Z. G., & Tracey, J. G. (2008). Toward a fuller conception of machismo: Development of a traditional machismo and caballerismo scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 55(1), 19–33. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.55.1.19

- Arredondo, P., & Tovar-Blank, Z. G. (2014). Multicultural competencies: A dynamic paradigm for the 21st century. In F. T. L. Leong, L. Comas-Díaz, G. C. N. Hall, V. C. McLoyd, & J. E. Trimble (Eds.), APA handbook of multicultural psychology, Vol. 2. Applications and training (pp. 19–34). American Psychological Association.

- Barrita, A. (2021). Presumed Illegal Microaggressive Experience (PRIME): A microaggression targeting Latinx individuals. UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones, 4231. https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations/4231

- Barrita, A., & Wong-Padoongpatt, G. (2021). Resilience and Queer people. In K. Strunk & S. A. Shelton (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Queer Studies in Education (1st ed., Vol. 4, pp. 600–605). Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004506725_118

- Bouris, A., Guilamo-Ramos, V., Pickard, A., Shiu, C., Loosier, P. S., Dittus, P., Gloppen, K., & Michael Waldmiller, J. (2010). A systematic review of parental influences on the health and well-being of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth: Time for a new public health research and practice agenda. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 31(5), 273–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-010-0229-1

- Brooks, V. R. (1981). Minority stress and lesbian women. Free Press.

- Cadenas, G. A., & McWhirter, E. H. (2022). Critical consciousness in vocational psychology: A vision for the next decade and beyond. Online First. Journal of Career Assessment, 30(3), 411–435. https://doi.org/10.1177/10690727221086553

- Cahill, K. M., Updegraff, K. A., Causadias, J. M., & Korous, K. M. (2021). Familism values and adjustment among Hispanic/Latino individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 147(9), 947–985. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000336

- Cardoso, J. B., Szlyk, H. S., Goldbach, J., Swank, P., & Zvolensky, M. J. (2018). General and ethnic-biased bullying among Latino students: Exploring risks of depression, suicidal ideation, and substance use. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 20(4), 816–822. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-017-0593-5

- Cavey, M. Y. (2021). Beyond social mobility: A student-centered analysis of the aspirations of rural Latinx students [ Doctoral dissertation]. University of California.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, June 15). COVID data tracker. US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data

- Cerezo, A., Ching, S., & Ramirez, A. (2021). Healthcare access and health-related cultural norms in a community sample of Black and Latinx sexual minority gender expansive women. Online First. Journal of Homosexuality, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2021.1999123

- Chaiton, M., Musani, I., Pullman, M., Logie, C. H., Abramovich, A., Grace, D., & Baskerville, B. (2021). Access to mental health and substance use resources for 2SLGBTQ+ youth during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11315. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111315

- Chavez, L. (2013). The Latino threat: Constructing immigrants, citizens, and the nation (2nd ed.). Stanford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780804786188

- Chavez-Dueñas, N. Y., Adames, H. Y., & Organista, K. C. (2014). Skin-color prejudice and within-group racial discrimination: Historical and current impact on Latino/a populations. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 36(1), 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986313511306

- Collins, P. H. (2000). Black feminist thought. Routledge.

- Collins, M. (2022). Heterosexism. In The Palgrave encyclopedia of sexuality education. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-95352-2_3-1

- Cortés-García, L., Hernandez Ortiz, J., Asim, N., Sales, M., Villareal, R., Penner, F., & Sharp, C. (2022). COVID-19 conversations: A qualitative study of majority Hispanic/Latinx youth experiences during early stages of the pandemic. Child & Youth Care Forum, 51(4), 769–793. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-021-09653-x

- Courtwright, S. E. (2022). Do positive health assets influence how adolescents with chronic conditions access, utilize, and engage with the children’s mental health system during the COVID-19 pandemic?

- Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. The University of Chicago Legal Forum, 139–167.

- Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

- D’Costa, S., Rodriguez, A., Grant, S., Hernandez, M., Alvarez Bautista, J., Houchin, Q., Brown, A., & Calcagno, A. (2021). Outcomes of COVID-19 on Latinx youth: Considering the role of adverse childhood events and resilience. School Psychology, 36(5), 335–347. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000459

- Delgado-Romero, E. A., Nevels, B. J., Capielo, C., Galván, N., & Torres, V. (2013). Culturally alert counseling with Latino/Latina Americans. In G. J. McAuliffe (Ed.), Culturally alert counseling: A comprehensive introduction (2nd ed., pp. 293–314). Sage.

- Estrada, F., Cerezo, A., & Ramirez, A. (2021). An examination of posttraumatic stress disorder–related symptoms among a sample of Latinx sexual-and gender-minority immigrants. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 34(5), 967–976. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22714

- Falicov, C. J. (2014). Psychotherapy and supervision as cultural encounters: The multidimensional ecological comparative approach framework.

- Fish, J. N. (2020). Future directions in understanding and addressing mental health among LGBTQ youth. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 49(6), 943–956. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2020.1815207

- Gattamorta, K., & Quidley-Rodriguez, N. (2018). Coming out experiences of Hispanic sexual minority young adults in South Florida. Journal of Homosexuality, 65(6), 741–765. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2017.1364111

- Gattamorta, K. A., Salerno, J., & Quidley-Rodriguez, N. (2019). Hispanic parental experiences of learning a child identifies as a sexual minority. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 15(2), 151–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2018.1518740

- Gaxiola Romero, J. C., Pineda Domínguez, A., Gaxiola Villa, E., & González Lugo, S. (2022). Positive family environment, general distress, subjective well-being, and academic engagement among high school students before and during the COVID-19 outbreak. School Psychology International, 43(2), 111–134. https://doi.org/10.1177/01430343211066461

- Gonzalez, K. A., Abreu, R. L., Arora, S., Lockett, G. M., & Sostre, J. (2021). “Previous resilience has taught me that I can survive anything:” LGBTQ resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 8(2), 133–144. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000501

- Hawke, L. D., Hayes, E., Darnay, K., & Henderson, J. (2021). Mental health among transgender and gender diverse youth: An exploration of effects during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 8(2), 180–187. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000467

- Hibbs, C. (2014). Cissexism. In T. Teo (Ed.), Encyclopedia of critical psychology. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-5583-7_679

- Huang, B. Z., Creekmur, B., Yoo, M. S., Broder, B., & Sharp, A. L. (2022). Healthcare utilization among patients diagnosed with COVID-19 in a large integrated health system. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 37(4), 830–837. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07139-z

- Hwahng, S. J., Allen, B., Zadoretzky, C., Barber, H., McKnight, C., & Des Jarlais, D. (2019). Alternative kinship structures, resilience and social support among immigrant trans Latinas in the USA. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 21(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2018.1440323

- Jacobson, M., Chang, T. Y., Shah, M., Pramanik, R., & Shah, S. B. (2021). Racial and ethnic disparities in SARS-CoV-2 testing and COVID-19 outcomes in a Medicaid managed care cohort. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 61(5), 644–651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2021.05.015

- Jones, B. A., Bowe, M., McNamara, N., Guerin, E., & Carter, T. (2021). Exploring the mental health experiences of young trans and gender diverse people during the Covid-19 pandemic. International Journal of Transgender Health, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2021.1890301

- Jones, E. A., Mitra, A. K., & Bhuiyan, A. R. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on mental health in adolescents: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2470. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052470

- Kellogg, M. C. (2022). Oiremos: The development, implementation, and evaluation of a holistic health curriculum for a Hispanic youth enrichment program.

- Kohl, C., McIntosh, E. J., Unger, S., Haddaway, N. R., Kecke, S., Schiemann, J., & Wilhelm, R. (2018). Online tools supporting the conduct and reporting of systematic reviews and systematic maps: A case study on CADIMA and review of existing tools. Environmental Evidence, 7(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13750-018-0115-5

- Leidman, E., Duca, L. M., Omura, J. D., Proia, K., Stephens, J. W., & Sauber-Schatz, E. K. (2021). COVID-19 trends among persons aged 0–24 years—United States, March 1–December 12, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 70(3), 88–94. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7003e1

- Lozano, A., Fernandez, A., Tapia, M. I., Estrada, Y., Juan Martinuzzi, L., & Prado, G. (2021). Understanding the lived experiences of Hispanic sexual minority youth and their parents. Family Process, 60(4), 1488–1506. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12629

- Martinez, W., Patel, S. G., Contreras, S., Baquero Devis, T., Bouche, V., & Birman, D. (2022). “We could see our real selves:” the COVID-19 syndemic and the transition to telehealth for a school-based prevention program for newcomer Latinx immigrant youth. Journal of Community Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22825

- Mayo, Y. (1997). Machismo, fatherhood and the Latino family: Understanding the concept. Journal of Multicultural Social Work, 5(1–2), 49–61. https://doi.org/10.1300/J285v05n01_05

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

- Moore, K. S. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on the Latinx population: A scoping literature review. Public Health Nursing, 38(5), 789–800. https://doi.org/10.1111/phn.12912

- Muñoz-laboy, M., Leau, C. J. Y., Sriram, V., Weinstein, H. J., Del Aquila, E. V., & Parker, R. (2009). Bisexual desire and familism: Latino/a bisexual young men and women in New York City. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 11(3), 331–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691050802710634

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., & Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 10(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4

- Penner, F., Ortiz, J. H., & Sharp, C. (2021). Change in youth mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in a majority Hispanic/Latinx US sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 60(4), 513–523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2020.12.027

- Platero, R. L., & López-Sáez, M. Á. (2020). Support, cohabitation and burden perception correlations among LGBTQA+ youth in Spain in times of COVID-19. Journal of Children’s Services, 15(4), 221–228. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCS-07-2020-0037

- Poulson, M., Neufeld, M., Geary, A., Kenzik, K., Sanchez, S. E., Dechert, T., & Kimball, S. (2021). Intersectional disparities among Hispanic groups in COVID-19 outcomes. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 23(1), 4–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-020-01111-5

- Przeworski, A., & Piedra, A. (2020). The role of the family for sexual minority Latinx individuals: A systematic review and recommendations for clinical practice. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 16(2), 211–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2020.1724109

- Raymond-Flesch, M., Siemons, R., Pourat, N., Jacobs, K., & Brindis, C. D. (2014). A qualitative study of the health concerns and health care access of Latino “DREAMers. Journal of Adolescent Health, 55(3), 323–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.05.012

- Richter, S. K. (2022). The effects of remote learning on SLIFE students from Central America during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Riggle, E. D. B., Drabble, L. A., Bochicchio, L. A., Wootton, A. R., Veldhuis, C. B., Munroe, C., & Hughes, T. L. (2021). Experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic among African American, Latinx, and White sexual minority women: A descriptive phenomenological study. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 8(2), 145–158. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000510