ABSTRACT

Objective

This study assessed perceptions of Clinical Psychology doctoral programs’ efforts to recruit and retain faculty and graduate students of color, as well as differences in perceptions based on participants’ position within their program (i.e. graduate student versus faculty) and race.

Method

Participants (n = 297; 35% people of color; 79% female; mean age: 32) were graduate students and faculty from Clinical Psychology doctoral programs who completed an anonymous online survey about their programs’ efforts to recruit and retain graduate students and faculty of color; sense of belonging and perceptions of racial discrimination within programs; and experiences of cultural taxation and racism within programs.

Results

Faculty (n = 95) reported significantly greater perceptions of recruitment and retention efforts and fewer perceptions of racial discrimination than did graduate students (n = 202). Asian (n = 31), Black (n = 25), and Latinx (n = 35) participants reported significantly fewer perceptions of recruitment and retention efforts, less sense of belonging, and greater perceptions of racial discrimination than did White participants (n = 192). Cultural taxation was common among participants of color, and approximately half (47%) reported they have considered leaving academia – and approximately one third (31%) have considered leaving their program – due to experiences of racism in their program or field.

Conclusions

Cultural taxation and racial discrimination were common among scholars of color in this sample. Whether intentional or not, these experiences contribute to racially-toxic environments and negatively impact the racial diversity of the mental health workforce.

Introduction

Despite significant advances in our understanding of child and adolescent mental health, youth of color continue to experience inequitable access to and utilization of mental health services (Cummings & Druss, Citation2011, Citation2011). These disparities present across a range of disorders (Cummings & Druss, Citation2011; Magaña et al., Citation2013; Merikangas et al., Citation2011). Although several factors are postulated to contribute to mental health service utilization among people of color, such as mental illness stigma (Nadeem et al., Citation2007) and provider biases (Burgess et al., Citation2004), this paper focuses specifically on the limited diversity of the psychology workforce as a key contributor.

Meeting the mental health needs of youth of color and their families requires a research and clinical service workforce that is racially and ethnically representative of the population it serves. The U.S. population is becoming increasingly diverse, with projections that people of color will constitute a numerical majority – a “majority-minority” - by 2043 (U.S. Census Bureau, Citation2018). Unfortunately, psychology has not kept pace with these demographic shifts in terms of recruiting and retaining psychologists of color. According to recent data, 4% of practicing psychologists in the United States workforce are Asian, 4% Black, 6% Hispanic, 84% White, and 2% “other” (American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and two or more races) (U.S. Census Bureau, Citation2018). Racial disparities in the academic workforce are also evident, as only 17% of psychology faculty identify as people of color compared to 83% who identify as White (Bichsel et al., Citation2019).

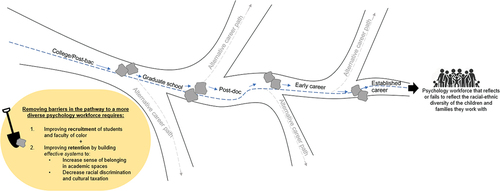

Pursuing a career in professional psychology is a long academic path, one that exists alongside a multitude of competing careers outside of psychology (see ). Barriers to building a racially diverse psychology workforce exist at each academic stage along this path, and at each transitional “fork,” students must reflect on the barriers and perceived benefits they face to decide whether to continue in psychology or move toward a different career. Although people of color are underrepresented at all academic levels, these disparities increase at each “fork” along the path from undergraduate to graduate school to higher professional ranks (e.g., postdoctoral to early- and senior-career positions) (U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Citation2019). This paper focuses specifically on how Clinical Psychology doctoral programs contribute to graduate students’ and faculty members’ decisions to stay on the professional psychology path, the gatekeeping behaviors that exclude people of color from entering the field, and racist climates that push them out.

Figure 1. Conceptual model of institutional changes needed to improve the pathway to a more diverse workforce in clinical psychology by increasing recruitment and retention of students and faculty of color.

Faculty involved in applicant selection often attribute low numbers of graduate students and faculty of color to limited racial diversity among applicants, rather than acknowledging that proactive recruitment of scholars of color is necessary to create a diverse professional psychology workforce. Proactive recruitment efforts might include sharing information about graduate training and faculty positions with relevant organizations and listservs (e.g., Tribal Colleges and Universities; APA Division 45 Society for the Psychological Study of Culture, Ethnicity and Race). In addition to use of active recruitment strategies, other factors that may influence a program’s ability to recruit scholars of color include perceived campus climate, existing representation of people of color in the program, and financial support (Griffin et al., Citation2012; Muñoz-Dunbar & Stanton, Citation1999; Poock, Citation2007). Notably, research suggests that faculty of color are more likely than White faculty to report that recruitment and retention practices are biased or insufficient to foster a diverse workforce (Price et al., Citation2005, Citation2009).

Although recruitment is an important aspect of enhancing workforce diversity, the small percentage of people of color in senior positions suggest that retention is also a substantial problem (e.g., 1% of full professors are Latina compared to 5% of instructors and 3% of assistant professors; U.S. Department of Education, Citation2019). Beyond general challenges of academia faced by all scholars, graduate students and faculty of color at predominantly White institutions are also burdened by race-related stressors, including racism and discrimination within their departments (Clark et al., Citation2012; Solórzano et al., Citation2000; Williams, Citation2019). Moreover, faculty of color are routinely asked to undertake extra service responsibilities, such as serving on diversity, equity, and inclusion committees or mentoring graduate students and junior faculty of color. Also known as “cultural taxation” (Padilla, Citation1994), these additional service obligations are often invisible forms of labor that are undervalued and receive limited recognition in terms of tenure and promotion decisions (Samano, Citation2007). Cultural taxation can thus impede career progress. Collectively, racial discrimination and cultural taxation may communicate to scholars of color that they are unwelcome within academic departments and organizations, contributing to heightened stress and decreased sense of belonging, and in some cases, effectively pushing them out of academia. For example, in a study of school psychology graduate students, students of color experienced more race-based microaggressions and less belongingness in their program compared to European Americans, and lower belongingness was associated with lower levels of academic engagement (Clark et al., Citation2012). Existing research on experiences of faculty of color across disciplines also highlights that cultural taxation and racism are common experiences that impact belongingness, emotional wellbeing, and career progress (Eagan & Garvey, Citation2015; Joseph & Hirshfield, Citation2011; Settles et al., Citation2019).

To date, few studies have quantitatively examined issues related to gatekeeping specifically in Clinical Psychology PhD and PsyD (doctoral) programs. Although Counseling PhD programs have many similarities with Clinical Psychology doctoral programs, there are some considerable differences in training environments that warrant separate analysis (Norcross et al., Citation2020). Given the role of graduate programs in training the next generation of psychologists, an empirical investigation of gatekeeping practices is essential to understanding factors contributing to lack of diversity among psychologists. Further, over the past two years, we have witnessed many Clinical Psychology programs voice a commitment to advancing anti-racism and promoting racial equity; many programs have formed new committees to lead anti-racism initiatives and made statements on racial justice that can be found on their websites. It is now critical to assess where we are as a field in terms of current antiracism efforts to continue this momentum.

Present Study

Leveraging original data from an online national survey of graduate students and faculty in Clinical Psychology doctoral programs, the present study sought to assess perceptions of programs’ efforts to recruit and retain faculty and graduate students of color. We additionally examined graduate student and faculty perceptions of the cultural climate in their programs more broadly, including their sense of belongingness and experiences of racial discrimination and cultural taxation. For each of these assessments, we aimed to examine whether findings differed based on participants:’ (1) position within their program (i.e., graduate student versus faculty) and (2) race. We hypothesized that compared to White participants, participants of color would: (1) be less likely to believe their program makes intentional efforts to increase representation of graduate students and faculty of color via active recruitment and retention practices; (2) report a lower sense of belonging in their program; and (3) be more likely to report perceiving racial discrimination within their program. Questions concerning personal experiences of cultural taxation and racial discrimination were only asked of participants of colorFootnote1; no a priori hypotheses were made regarding differences in experiences of cultural taxation and racism between different racial groups based on the dearth of research on this topic. Directionality of differences based on position (student versus faculty) was not specified for any analysis, similarly due to scarcity of extant research to inform predictions.

Method

Participants

Participants were 297 graduate students and faculty from Clinical Psychology doctoral programs who completed an anonymous online survey. Participants in the current study were: (1) graduate students currently enrolled in an APA-accredited Clinical Psychology PhD or PsyD program or currently completing their predoctoral clinical internship; (2) faculty in an APA-accredited Clinical Psychology PhD or PsyD program, including tenured, tenure-track, and non-tenure track faculty; and/or (3) Directors of Clinical Training (DCTs) in an APA-accredited Clinical Psychology PhD or PsyD program.

Procedures

The University’s Institutional Review Board approved the study. To recruit participants, an anonymous online survey was distributed through social media, listservs, and eemails to department chairs, DCTs, and administrative assistants in Clinical Psychology doctoral programs. We emailed approximately 261 DCTs of Clinical Psychology PhD programs and 60 DCTs of PsyD programs asking them to share the survey link with graduate students, faculty, and clinical supervisors in their programs.

Interested participants were directed to the University’s Qualtrics platform. Participants completed a brief, web-based screener to confirm eligibility. Individuals who met inclusion criteria provided informed consent and were directed to the study survey which took, on average, 25 minutes to complete. Data were collected between April 2021 and August 2021 — this end date was selected to preclude data collection spanning across multiple school years, as incoming graduate students may have limited knowledge of program culture when they first join their programs. Compensation for participation was not provided.

Analytic Sample

A total of 498 people visited the survey website, and 352 met the criteria for enrollment and provided informed consent. Thirty-five individuals (10%) provided consent but exited the survey before answering any questions, leaving a sample of 317 participants. Three respondents were excluded from the present study due to not identifying as faculty or graduate student (i.e., clinical supervisor only), and 17 participants ended the survey prior to responding to at least one key variable of interest, leaving a final analytic sample of 297 participants. Of these, 260 participants (88%) reported their school affiliation, resulting in the present sample representing at least 103 unique schools. Thirty-three schools were represented by responses from at least one faculty and one graduate student, 23 by faculty only, and 47 by graduate student(s) only. Responses from participants who elected not to report school affiliation were approximately split evenly between graduate students (n = 18) and faculty (n = 19).

provides demographic characteristics of the sample. Approximately two thirds of participants were graduate students (n = 202; 68%) and a third were faculty (n = 95; 32%). Participants were predominantly female (n = 234; 79%), heterosexual (n = 196; 66%), and born in the United States (n = 258; 87%). The mean age of the full sample was 32 years (SD = 9.77; graduate students: M = 27, SD = 3.72; faculty: M = 44, SD = 9.38). Participants were disproportionately from Clinical Psychology PhD programs (n=267; 90%) and were affiliated with programs from diverse geographic regions (urban: n = 143, 48%; rural: n = 51, 17%; suburban: n = 96, 32%; other: n = 7, 2%). More than half of participants reported that both of their parents graduated from college (n = 173; 58%) and approximately a quarter indicated that neither of their parents had graduated from college (n = 72; 24%). Regarding race, less than 1% (n = 2) of participants identified as American Indian or Alaska Native, 10% Asian (n = 31), 8% Black (n = 25), 12% Hispanic/Latinx (n = 35), 2% Middle Eastern or North African (n = 7), 65% White (n = 192), 1% Other (n = 4), and one person declined to provide their race. Based on the race prevalence in the sample, we created five race subgroups for further analysis that included: (1) Non-Hispanic White; (2) Non-Hispanic Black; (3) Non-Hispanic Asian; (4) Hispanic/Latinx; and (5) Multiracial/Other. Participants in the first three categories answered affirmatively to White, Black, or Asian, respectively, and “no” to all other race items. The Hispanic/Latinx category includes any participants who identified as Hispanic/Latinx regardless of the race they endorsed. Multiracial includes participants who selected more than one race (and did not endorse Hispanic), while “Other” includes participants who self-identified as American Indian, Alaska Native, Middle Eastern, North African, or Other (and did not endorse Hispanic). Due to significant heterogeneity in the racial identity of participants in the Multiracial/Other category and the small sample size of each group comprising the Multiracial/Other category, analyses assessing subgroup differences based on race excluded participants in this group.

Table 1. Race, gender, and sexual orientation frequencies by position.

Measures

Perceptions of Program-Level Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Initiatives

Items included in the present report are listed in . Based on limited availability of validated measures for assessing diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives in graduate programs, study authors developed items to assess these efforts, drawing on recently proposed approaches for advancing anti-racism in Clinical Psychology (Galán et al., Citation2021). Items assessed perceptions of efforts made by Clinical Psychology doctoral programs to recruit graduate students and faculty of color (e.g., “How often does your program use active outreach and recruitment strategies to attract a racially diverse pool of graduate students?”). Indices of programs’ efforts to retain graduate students and faculty of color included: (1) experiences of cultural taxation among faculty and students of color (e.g., “As a faculty member/graduate student who self-identifies as BIPOC, I have felt pressured to take on extra work that is uncompensated because of my race.”); (2) programs’ response to highly publicized acts of racism (e.g., “Following highly publicized or local traumatic racial injustice events, my department has coordinated support and mental health resources to address these traumatic racial injustice events.”); (3) promotion of anti-racist action (e.g., “The faculty and in-house supervisors in my program have cultivated a culture in which individuals – particularly, White allies – are encouraged to intervene after witnessing racial microaggressions or other oppressive actions in their professional environment.”); and (4) provision of mental health support for graduate students of color (“I am aware of at least one mental health and resilience promotion resource at or near my graduate institution that is accessible and free/low-cost for BIPOC students.”)Footnote2

Table 2. Perceptions of programs’ efforts to recruit and retain graduate students and faculty of color: differences by participants’ race.

Additionally, to assess participants’ sense of belonging and perceptions of racial discrimination within Clinical Psychology programs, we used selected items from the Psychological Sense of School Membership Scale (e.g., “Sometimes I feel as if I do not belong here;” Goodenow, Citation1993), the School Racial Conflict Resolution Scale (e.g., “I have witnessed overt racist acts in my program;” Coleman & Stevenson, Citation2013), and the School Racial Awareness and Assertiveness Scale (e.g., “I have seen and heard stereotypes about other racial groups in my program;” Coleman & Stevenson, Citation2013). Constraints on survey length precluded the use of all items from these measures. Survey items were piloted by current and past graduate students and faculty members who did not participate in the final study. For full survey questions and response options, see Open Science Framework (OSF) registration (https://osf.io/9qd6p).

Analytic Plan

The analytic plan was registered on OSF (https://osf.io/9qd6p). Inter-item correlations were computed for items relating to the same construct (e.g., recruitment of graduate students of color), and items that were correlated at or above r ≥ .70 were averaged. Although 297 participants responded to at least one of the key variables of interest, some participants did not complete the entire survey. The number of respondents for each item is reported in (and supplementary Tables S1-S3).Footnote3

Table 3. Sense of belongingness and perceptions of racial discrimination within clinical psychology programs: differences by participants’ race.

Table 4. Personal experiences of cultural taxation and racism within clinical psychology programs: differences by participants’ race.

To test our primary aims regarding programs’ efforts to recruit and retain graduate students and faculty of color, we estimated descriptive statistics (i.e., frequencies, means, and standard deviations) for all key variables for the entire sample, as well as separately based on participants’ position in their program (i.e., graduate student versus faculty) and race (i.e., Hispanic/Latinx, Non-Hispanic Asian, Non-Hispanic Black, Non-Hispanic White). To assess differences based on position and race, one-way ANOVAs for continuous variables and Pearson’s chi-square tests for binary variables were used. Significant omnibus tests were followed by pairwise comparisons. We first computed models without accounting for clustering of participants within schools. Subsequent analyses accounted for clustering using multilevel mixed models; however, 12% of participants (n = 37) were excluded from these analyses as they declined to report the name of their school. The general pattern of findings remained consistent regardless of accounting for clustering. Analyses not accounting for clustering are reported in text to ensure that participants who did not provide their school’s name were represented in our findings. Results from analyses accounting for clustering are provided in the online supplement (Tables S4–S10). Significance cutoffs were set at p < .05 for all analyses. Analyses were conducted in SPSS 27.0 (IBM Corp, Citation2017) and R (Team, Citation2013).

Results

In only two instances did inter-item correlations meet the r ≥ .70 threshold for combining items. We averaged scores on “My program makes a serious effort to recruit BIPOC graduate students” and “My program makes a serious effort to recruit BIPOC faculty” (r = 0.73). We also averaged responses to “As a faculty member/graduate student who self-identifies as BIPOC, I have felt pressured to take on extra work that is uncompensated because of my race” and “As a self-identified BIPOC faculty member/graduate student, I take on more service activities (e.g., committee assignments, diversity-related work) than my colleagues because of my race” (r = 1.00).

Differences in missingness on each of the outcome variables based on position (faculty vs. graduate student) and race, respectively was evaluated. Significant differences in missingness based on position were observed for two items. For one item asking about whether following racial injustice events there were faculty meetings dedicated to discussing the impact of these events on students, there was significantly more missing data for graduate students, which we suspect may reflect graduate students not having necessary knowledge to respond to this item. The second item asked about opportunities to receive mentorship from someone of their own race/ethnicity during their time in the program. For this item, significantly more faculty had missing data, which may reflect faculty not perceiving the question to be applicable to them (i.e., faculty may not have opportunities for mentorship). Missingness based on race analyses revealed significant differences for six of the belongingness items and two of the racial discrimination items. Across these items, there was consistently more missingness based on race in the following order: Asian, Latinx, White, then Black. Given the consistency in percent missingness, we suspect this is a function of participants having exited the survey early, rather than selecting to opt out of specific items. See online supplement for full results of missing data analyses (Tables S11-S12).

Perceptions of Clinical Psychology Program Efforts to Recruit and Retain Graduate Students and Faculty of Color

We sought to describe perceptions of programs’ efforts to intentionally increase the representation of graduate students and faculty of color via recruitment practices, as well as to explore differences in these perceptions based on position and race. See and S1 for descriptive statistics and subgroup analysis results. Approximately two thirds of participants (68%) agreed (i.e., endorsed “slightly agree,” “mostly agree,” or “strongly agree”) that their program engages in intentional recruitment of graduate students and faculty of color. Compared to White participants, Asian, Black, and Latinx participants were significantly less likely to believe that their program makes a serious effort to recruit graduate students and faculty of color. Asian, Black, and Latinx participants did not differ significantly from one another in their perceptions of programs’ recruitment efforts. Further, when examining differences in perceptions based on position in program, graduate students were significantly less likely than faculty to agree that their program engages in intentional recruitment of graduate students and faculty of color (see online supplementary Table S1).

Faculty (but not graduate students) also reported how often their program uses targeted outreach and recruitment strategies to attract a racially diverse pool of graduate and faculty applicants. Approximately half of respondents (51%) endorsed that their program engages in such efforts more than half the time (i.e., “most of the time” or “always”) to recruit graduate students. In comparison, 61% of respondents endorsed such efforts were used more than half the time to recruit candidate faculty of color. There were no significant differences by race on this variable ().

Next, we assessed perceptions of programs’ efforts to create a culture that supports the retention of graduate students and faculty of color. Faculty were significantly more likely than graduate students to endorse awareness of mental health and resilience promotion resources accessible to students of color (Table S1). Within the race subgroup analyses, Black participants were most likely and Asian participants were least likely to report awareness of such mental health resources (). Although there was not a significant difference between graduate students and faculty in having opportunities to receive mentorship by someone of their own race, there was a significant difference by participant race, with White participants (93%) most likely to endorse having had such an opportunity. Graduate students (but not faculty) also reported how much they agreed with being comfortable talking to their faculty mentors about race-related topics, with two fifths of participants (40%) endorsing disagreement. Asian graduate students were significantly less likely to endorse feeling comfortable talking to their faculty mentor about race-related topics compared to White and Black participants ().

Regarding programs' promotion of anti-racist action, 56% of participants agreed (i.e., “slightly agree,” “mostly agree,” or “strongly agree”) that their program had created a culture in which individuals are encouraged to intervene in response to racial microaggressions and other oppressive actions. Graduate students agreed significantly less with this statement than did faculty (Table S1). When examining differences in perceptions based on participant race, Asian, Black, and Latinx participants were significantly less likely than White participants to believe that their program encourages intervention in response to racial microaggressions (). Asian, Black, and Latinx participants did not significantly differ from one another in these perceptions.

Next, we examined programs’ responses to highly publicized and local traumatic racial injustice events. In total, 62% of participants indicated that their program publicly addresses the student body to acknowledge these events using e-mail or other communication methods more than half the time; 21% reported that their program acknowledges racial injustice events less than half the time (i.e., “never” or “seldom”). Compared to White participants, Asian participants reported that their program acknowledges racial injustices less frequently ().

We also assessed other program responses to racial injustices, including coordinating mental health resources, holding faculty meetings, and implementing other changes to minimize the negative impact of these traumatic events on students’ emotional well-being and academic trajectories (e.g., relieving research or clinical responsibilities). The majority of respondents indicated that their program has rarely responded to highly publicized or local traumatic events in these ways. For example, 77% of participants indicated that their program alleviates professional responsibilities following racial injustices less than half the time. When examining differences based on position in the program, compared to faculty, graduate students reported a lower frequency of alleviating professional responsibilities and holding faculty meetings to discuss the impact of these events on students (Table S1). There were no differences based on participant race in perceived frequency of coordinating mental health resources or holding a faculty meeting following racial injustices ().

Graduate Students and Faculty Sense of Belonging and Perceptions of Racial Discrimination Within Clinical Psychology Programs

Next, we examined faculty and student sense of belonging and perceptions of racial discrimination within Clinical Psychology doctoral programs. Graduate students and faculty did not significantly differ from one another in their self-reported sense of belonging in their programs (Table S2). Asian, Black, and Latinx participants reported a lower sense of belonging in their programs than did White participants ().

We also explored faculty and graduate student perceptions of racial discrimination within their programs. Over half of participants (56%) disagreed that their program handles racial conflict in an open and fair manner. When examining differences in perceptions based on position in program, graduate students were significantly less likely than faculty to agree that their program handles racial conflict appropriately (Table S2). Asian, Black, and Latinx participants each reported significantly less agreement with this statement than did White participants ().

Approximately a quarter of participants (25%) indicated that they have witnessed overt acts of racism in their program; there were no differences in these reports based on participant position or race. About a third of participants (32%) indicated that they have seen or heard racist stereotypes about their own race in their program, and around half (51%) reported seeing or hearing stereotypes about other races. Compared to faculty, graduate students were significantly more likely to report having seen or heard racist stereotypes about other races in their program (Table S2). When examining differences based on participant race, White participants were less likely than Asian, Black, and Latinx participants to indicate that they have perceived racist stereotypes about their own race or other races in their program ().

Graduate Student and Faculty of Color’s Experiences of Cultural Taxation and Racism Within Clinical Psychology Programs

Finally, we sought to assess graduate student and faculty of color experiences of cultural taxation and personal experiences of racism (as opposed to general perceptions of racial discrimination) within Clinical Psychology doctoral programs and academia broadly. These analyses were limited to participants of color (n = 90) as White participants were not asked to report on these experiences. Over half of participants of color (64%) indicated that they have felt pressured to take on more service activities (e.g., committee assignments, diversity-related work) because of their race than their colleagues (i.e., they endorsed “slightly agree,” “mostly agree,” or “strongly agree”). Approximately a third of participants of color (31%) reported that they have considered leaving their program because of racism they have experienced. Nearly half (47%) reported that they have considered leaving academia because of racism they have experienced in the field. There were no significant differences between graduate students and faculty or between Asian, Black, and Latinx participants in reported experiences of cultural taxation or racism. See and S3 for full model results.

Discussion

Racial inequities in access to and utilization of mental health services among children and adolescents demand interrogation of the systems and practices that fuel these disparities (Cummings et al., Citation2011). We argue that limited diversity of the psychology workforce is a key contributor to the underservice of people of color. As such, this study focused on assessing factors related to the recruitment and retention of graduate students and faculty of color in Clinical Psychology doctoral programs.

Perceptions of Clinical Psychology Program Efforts to Recruit and Retain Graduate Students and Faculty of Color

Results yielded only tepid endorsement that programs are making serious efforts to recruit graduate students and faculty of color or that programs have fostered a culture of antiracism (e.g., encouraging individuals to intervene against microaggressions and other oppressive actions within the professional environment). Significant differences based on position and race were revealed, such that faculty and White participants were more likely to report perceiving programs as making serious efforts in these domains compared to graduate students and Asian, Black, and Latinx participants. In some instances, such as recruitment efforts, differences based on position may result from limited awareness of such efforts among graduate students, suggesting a possible need for greater transparency between faculty and graduate students about initiatives to promote diversity. It is also important to note that differences between faculty and graduate students’ perceptions may be partially explained by demographic differences between faculty and students in this sample. Graduate students were more likely to identify as Asian, less likely to identify as White, and more likely to identify outside the gender binary than faculty. Unfortunately, we did not have a large enough sample size to examine the possibility of interactions between race and position. Differences in responses between faculty and graduate students may also be reflective of differences between programs, given that only about a third of schools (32%) represented in this sample had responses from both graduate students and faculty.

Though replication is needed to explore these demographic differences, our findings suggest that there is significant discrepancy in perceptions between graduate students and faculty regarding antiracism efforts in Clinical Psychology doctoral programs. To address this discrepancy, departments could consider regularly administering anonymous cultural climate surveys to both groups and compare responses (see Galán et al., Citation2021 for survey considerations). Survey results could be distributed to the department, and even shared publicly, for full transparency. Departments could consider implementing town halls or faculty meetings that are open to graduate students, during which departmental progress toward antiracism can be discussed and input can be elicited from both graduate students and faculty.

Graduate Students and Faculty Sense of Belonging and Perceptions of Racial Discrimination Within Clinical Psychology Programs

Asian, Black, and Latinx participants endorsed feeling a decreased sense of belonging within their programs compared to White participants. Recognizing belongingness as a fundamental human need (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995), this should be of significant concern in efforts to retain graduate students and faculty of color. There are numerous factors that may contribute to diminished sense of belonging among graduate students and faculty of color, including limited racial diversity within programs, experiences of racial microaggressions, and expected assimilation to White, patriarchal standards of professionalism in academia (McCluney et al., Citation2021; Mirza, Citation2018; Pittman, Citation2012). Joseph and Hirshfield (Citation2011) also discuss “differential legitimacy,” or graduate students and faculty of color carrying the extra burden of legitimizing their qualifications, as a form of cultural taxation that leads to less belongingness within academia.

Our findings suggest that there is a need for departments to enact specific initiatives to promote belongingness among graduate students and faculty of color. Providing regular “safe spaces” for graduate students or faculty of color can promote social support and connectedness, help process microaggressions, and communicate to people of color that the department is actively invested in their wellbeing (Blackwell, Citation2018; Galán et al., Citation2021; Grier-Reed et al., Citation2016; Grier‐reed, Citation2010). Providing adequate mentorship to students and faculty of color is also critical in developing a sustained sense of belonging (Cohen & Steele, Citation2002; Maestas et al., Citation2007; Wright-Mair, Citation2020). Mentorship from other people of color can be particularly beneficial (Blake-Beard et al., Citation2011) and may necessitate that departments with few faculty of color create cross-departmental mentorship initiatives and/or provide faculty and graduate students of color with access to national mentorship and career development resources (Galán et al., Citation2021). We additionally recommend a series of mentoring guides published in affiliation with the William T. Grant Foundation that offers strategies for building supportive mentoring relationships, such as how to mentor across differences and how to help researchers of color navigate institutional barriers in academia (Ammerman & Tseng, Citation2011; Louie & Wilson-Ahlstrom, Citation2018; Wilson-Ahlstrom et al., Citation2017). Finally, given that experiences of racism are associated with a decreased sense of belongingness (Clark et al., Citation2012), initiatives that reduce racial discrimination within departments, which we describe below, also may promote belongingness.

Graduate Student and Faculty of Color’s Experiences of Cultural Taxation and Racism Within Clinical Psychology Programs

It is important that efforts to increase belongingness do not result in people of color assuming more responsibilities, which would increase cultural taxation and exacerbate existing inequities. Importantly, our study demonstrated that scholars of color are experiencing high rates of cultural taxation. Combating cultural taxation requires that students and faculty of color have the option to reduce their service activities if they wish, while also acknowledging that some people of color may greatly value this work and wish to continue engaging in it. In fact, suggesting that people of color reduce their service activities may send the message that this work is not meaningful or important, which is a microaggression in itself. Thus, departments should also recognize and reward these efforts (Galán et al., Citation2021).

While study findings suggest that programs are making efforts to proactively recruit faculty and students of color, the high rates of cultural taxation and racial discrimination reported in this study underscore that simply admitting students or hiring faculty of color is not the same as cultivating an inclusive, anti-racist climate. Although it is generally no longer acceptable to engage in overtly discriminatory behavior, more subtle forms of discrimination, or racial microaggressions, are pervasive. Unfortunately, we did not collect data regarding the specific types of racial microaggressions experienced by individuals of color within Clinical Psychology programs. However, examples documented in the broader literature on racial microaggressions include tokenism (e.g., emphasizing the recent hire of faculty of color as “evidence” of commitment to diversity and inclusion while doing little to embed these principles into program culture; Settles et al., Citation2019), environmental exclusions (e.g., only depicting photos of White people in building art; Harwood et al., Citation2012), and assuming that people of a given race are all alike (e.g., a teacher expecting a student to be a spokesperson for their race; Williams et al., Citation2021). Future research is needed to characterize how racial microaggressions specifically manifest within Clinical Psychology programs.

Although racial microaggressions are sometimes dismissed as simple cultural blunders, as noted by Williams et al. (Citation2021), “Microaggressions, however, are not innocuous errors; rather, they are a form of oppression that reinforces unjust power differentials between groups, whether or not this was the conscious intention of the offender.” Although we did not collect data on how individuals in our sample have been impacted by experiences of discrimination within their programs, there is an extensive body of research linking racial discrimination with negative mental and physical health and academic outcomes (Hurd et al., Citation2014; Jackson et al., Citation2010; Steketee et al., Citation2021). Further, one third to nearly one half of participants of color in our study reported that they have considered leaving their program or academia due to the racism they have experienced. These findings underscore that toxic racial climates not only affect the health and well-being of individual scholars of color within our programs, but they also have significant, downstream implications for the diversity of the mental health workforce.

The impact of these stressors is exacerbated when there are few trusted individuals in power to whom students feel safe speaking about experiences of racism. In particular, Asian graduate students in our study reported being less likely to talk to their faculty mentor about race-related incidents compared to White and Black students. The implications of these findings are particularly alarming given the ongoing rise in racism-based violence and discrimination targeted toward Asian individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic (Ruiz et al., Citation2021; Tessler et al., Citation2020). While we did not collect data regarding factors that may alter students’ willingness to speak with their advisors about race-related topics, we speculate that some students may avoid these discussions out of fear of having their experiences and perspectives invalidated (Wang et al., Citation2020; see also Lau et al., Citation2022).

Findings indicated that White participants were least likely to endorse having witnessed race-based stereotypes being made within their program. Although we do not have data to support a clear explanation, we believe this suggests a lack of attunement among White scholars to the harmful experiences endured by their colleagues of color. In reflecting on current practices that are within our control to change as academics and providers, this potential lack of racial awareness among White colleagues warrants swift and intentional remediation. Sue et al. (Citation2019) offer a thoughtful discussion of strategies that can be used by not only targets of microaggressions, but also White allies and bystanders, to intervene against discriminatory acts such as microaggressions. Galán et al. (Citation2021) also provide several concrete recommendations for cultivating inclusive, anti-racist programs, including trainings on how to identify and intervene in response to racial microaggressions. It is critical that included in these efforts are explicit discussions of Whiteness and how it privileges White graduate students and faculty while pushing scholars of color out of our programs, and in some cases, out of academia altogether.

It is important to note that experiences of racism within academic settings further compound the stress of interpersonal and structural racism experienced within society more broadly. Study results indicate that in general, Clinical Psychology programs have provided limited support to students of color following highly publicized or local traumatic racial injustice events. These findings demonstrate the ways in which academia tries to operate “business-as-usual,” without consideration of the larger socio-political context and events that shape students’ lives. Failing to recognize the ways in which scholars of color may be affected by these events functions as another type of racial microaggression that invalidates their lived experiences. Programs that desire to improve in this area should refer to Galán et al. (Citation2021), who provide several recommendations for minimizing the detrimental effects that racial traumas can have on students of color’s emotional wellbeing and academic trajectories. Additionally, programs should consider how to best support not only students of color, but faculty and staff of color as well.

Finally, as we continue to push for change in the recruitment and retention of graduate students and faculty of color, it is also important to acknowledge the progress that has been made thus far because of the persistence and leadership of graduate students and faculty dedicated to creating a more equitable and diverse psychology workforce. In recent years, many programs have reevaluated the ways in which graduate school admissions procedures may be maintaining inequities in recruitment. This is evident in the increasing number of programs that have permanently removed GRE scores as a requirement for applying to graduate school, a decision guided by evidence showing that the emphasis on GRE scores has disproportionately and unfairly excluded qualified Black, Indigenous, and Latinx students (Gómez et al., Citation2021). Moreover, Rogers and Molina (Citation2006) highlighted 11 “exemplary examples” of programs in psychology that have demonstrated success in recruiting and retaining graduate students of color. These institutions engaged in several common practices, such as regularly hiring faculty of color, ensuring that faculty of color are in visible leadership positions, including faculty and graduate students of color in recruitment efforts, offering substantial financial aid for students, creating opportunities for prospective students of color to meet with current students with shared backgrounds, facilitating dedicated spaces for peer support among students of color (e.g., mentorship or buddy networks), and establishing partnerships with historical institutions of color to facilitate pathways from college into graduate school. APA’s Suinn Minority Achievement Program Award also reviews and selects programs each year that have demonstrated excellence in the recruiting, retaining, and supporting the graduation of students of color in psychology doctoral programs.

Limitations

The current findings should be considered within the context of study limitations.

First, our sample was both self-selected and limited in size and therefore may not fully represent unique experiences of the graduate students and faculty who did not participate. Importantly, it is likely that individuals (and particularly White individuals) who opted to complete the survey are those more concerned with issues of diversity, equity and inclusion, thus it is reasonable to expect that a more representative sample might reveal a larger contrast in perceptions and experiences by race and position.

Moreover, though participants represented over 100 graduate programs from diverse geographical locations, the sample was predominately White and female. However, the demographics (racial and gender identity) of our sample of graduate students are closely matched to demographics of the larger population of clinical psychology graduate students (American Psychological Association [APA], Citation2021). The sample demographics (racial and gender identity) for faculty members in the present study are also similar to those of the larger population of psychology faculty members (not specific to clinical psychology) in 2015 (American Psychological Association [APA], Citation2019), with female faculty members possibly overrepresented in the present sample. Though we must continue making progress in diversifying our field, the sample recruited for the present study appears to reasonably reflect the current make-up of clinical psychology graduate students and faculty members, supporting generalizability of study findings.

Second, this report focused specifically on Clinical Psychology doctoral programs. It does not capture the perspectives of students and faculty in other mental health fields, such as Social Work or Counseling Psychology, which have historically been more advanced in their commitment to inclusivity and social justice training (Brown, Citation2021; Buchanan & Wiklund, Citation2020; Fouad et al., Citation2006). Given that the phrasing of the questions in the surveys best aligned with the experiences and requirements of Clinical Psychology doctoral programs, we elected to exclude counseling programs and other programs in the health services workforce from the present report.

Third, many questions used in the present study, including those examining recruitment and retention efforts, were developed by study authors. Future research should establish validated measures for assessing these key issues across health service training programs. Fourth, as faculty were disproportionately more likely to be White compared to graduate students, findings concerning position in program may be conflated with participant race. Unfortunately, the small sample size and limited participation of faculty in this study precluded us from disentangling effects of participant position and race. Relatedly, this study focused specifically on race and did not consider other aspects of participants’ social identities. Future studies incorporating larger sample sizes are needed for a more nuanced, intersectional analysis.

Finally, it is important to remember that eradicating mental health service inequities will require a multipronged approach and increasing the diversity of the psychology workforce is only part of the solution. We must continue to identify and address other factors contributing to these disparities, including insufficient training in cultural humility in our graduate programs (Galán et al., Citation2021), treatments that are not tailored to diverse youth (Willis et al., Citation2022), and lack of cost-effective and accessible systems of care.

Conclusions

Findings suggest that although several Clinical Psychology programs have been making efforts to recruit graduate students and faculty of color, there has been less attention to ensuring that these individuals are welcomed into warm, inclusive environments. We found that experiences of cultural taxation and racial discrimination were common amongst graduate students and faculty of color in our sample. Regardless of whether these experiences are the result of intentional discrimination, their effects are likely damaging nonetheless and may contribute to the loss of valuable potential professionals in the mental health workforce. These issues will not be resolved by quick fixes or Band-Aids (e.g., one-time trainings on racial microaggressions), but rather necessitate a commitment to critically interrogating and eradicating all forms of racism and systemic Whiteness in Clinical Psychology programs. Programs must begin to live out this commitment by overhauling recruitment efforts of diverse students and faculty and simultaneously taking proactive steps to improve departmental culture. We must hold our programs and one another accountable for making these changes to ensure that the next generation of researchers, practitioners, and educators are as diverse as the people with whom they work.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (63.9 KB)Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary Data

Supplemental material for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2023.2203930.

Notes

1 All participants were asked whether they have witnessed racism in their program. Only participants of color were asked about personal experiences of racism and cultural taxation.

2 BIPOC refers to Black, Indigenous, and People of Color. While we used this term in survey items, we have elected to move toward a more inclusive language of “people of color” and thus do not use “BIPOC” in this report aside from referring to specific phrasing of survey items.

3 Due to space constraints, we provide tables for race subgroup analyses in text and for position subgroup analyses in an online supplement.

References

- American Psychological Association. (2019). The academic psychology workforce: Characteristics of psychology research doctorates in faculty positions (1995-2015). Author.

- American Psychological Association. (2021). Graduate study in psychology: Demographics of departments of psychology [interactive data tool]. https://www.apa.org/education-career/grad/survey-data/demographics-data

- Ammerman, C., & Tseng, V. (2011). Maximizing mentoring: A guide for building strong relationships. The William T. Grant Foundation.

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

- Bichsel, J., Li, J., McChesney, J., & Pritchard, A. (2019, March). Faculty in higher education annual report: Key findings, trends, and comprehensive tables for tenure-track, non-tenure teaching, and non-tenure research faculty; academic department heads; and adjunct faculty for the 2018-19 academic year (Research Report). College and University Professional Association for Human Resources [CUPA-HR]. https://www.cupahr.org/surveys/results/

- Blackwell, K. (2018). Why people of color need spaces without White people. The Arrow. https://arrow-journal.org/why-people-of-color-need-spaces-without-white-people/

- Blake-Beard, S., Bayne, M. L., Crosby, F. J., & Muller, C. B. (2011). Matching by race and gender in mentoring relationships: Keeping our eyes on the prize. The Journal of Social Issues, 67(3), 622–643. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2011.01717.x

- Brown, C. (2021). Critical clinical social work and the neoliberal constraints on social justice in mental health. Research on Social Work Practice, 31(6), 1049731520984531. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731520984531

- Buchanan, N. T., & Wiklund, L. O. (2020). Why clinical science must change or die: Integrating intersectionality and social justice. Women & Therapy, 43(3–4), 309–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/02703149.2020.1729470

- Burgess, D. J., Fu, S. S., & Van Ryn, M. (2004). Why do providers contribute to disparities and what can be done about it? Journal of General Internal Medicine, 19(11), 1154–1159. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30227.x

- Clark, C. R., Mercer, S. H., Zeigler-Hill, V., & Dufrene, B. A. (2012). Barriers to the success of ethnic minority students in school psychology graduate programs. School Psychology Review, 41(2), 176–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2012.12087519

- Cohen, G. L., & Steele, C. M. (2002). A barrier of mistrust: How negative stereotypes affect cross-race mentoring. In J. Aronson (Ed.), Improving academic achievement (pp. 303–327). Academic Press.

- Coleman, S., & Stevenson, H. C. (2013). The racial stress of membership: Development of the faculty inventory of racialized experiences in schools. Psychology in the Schools, 50(6), 548–566. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21693

- Cummings, J. R., & Druss, B. G. (2011). Racial/Ethnic differences in mental health service use among adolescents with major depression. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 50(2), 160–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2010.11.004

- Cummings, J. R., Wen, H., & Druss, B. G. (2011). Racial/Ethnic differences in treatment for substance use disorders among US adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 50(12), 1265–1274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2011.09.006

- Eagan, M. K., Jr., & Garvey, J. C. (2015). Stressing out: Connecting race, gender, and stress with faculty productivity. The Journal of Higher Education, 86(6), 923–954. https://doi.org/10.1353/jhe.2015.0034

- Fouad, N. A., Gerstein, L. H., & Toporek, R. L. (2006). Social justice and counseling psychology in context. In R. L. Toporek, L. H. Gerstein, N. A. Fouad, G. Roysircar, & T. Israel (Eds.), Handbook for social justice in counseling psychology (pp. 1–16). Sage.

- Galán, C. A., Bekele, B., Boness, C., Bowdring, M. A., Call, C. C., Hails, K. A., McPhee, J., Mendes, S. H., Moses, J., Northrup, J. B., Rupert, P., Savell, S., Sequeira, S., Tervo-Clemmens, B., Tung, I., Vanwoerden, S., Womack, S. R., & Yilmaz, B. (2021). A call to action for an antiracist clinical science. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 50(1), 12–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2020.1860066

- Gómez, J. M., Caño, A., & Baltes, B. B. (2021). Who are we missing? Examining the graduate record examination quantitative score as a barrier to admission into psychology doctoral programs for capable ethnic minorities. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 15(3), 211–218. https://doi.org/10.1037/tep0000336

- Goodenow, C. (1993). The psychological sense of school membership among adolescents: Scale development and educational correlates. Psychology in the Schools, 30(1), 79–90. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6807(199301)30:1<79:AID-PITS2310300113>3.0.CO;2-X

- Grier‐reed, T. L. (2010). The African American student network: Creating sanctuaries and counterspaces with racial microaggressions in higher education settings. Journal of Humanistic Counseling, Education and Development, 49(2), 181–188. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1939.2010.tb00096.x

- Grier-Reed, T., Arcinue, F., & Inman, E. (2016). The African American student network: An intervention for retention. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 18(2), 183–193. https://doi.org/10.1177/1521025115584747

- Griffin, K. A., Muñiz, M. M., & Espinosa, L. (2012). The influence of campus racial climate on diversity in graduate education. The Review of Higher Education, 35(4), 535–566. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2012.0031

- Harwood, S. A., Huntt, M. B., Mendenhall, R., & Lewis, J. A. (2012). Racial microaggressions in the residence halls: Experiences of students of color at a predominantly White university. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 5(3), 159–173. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028956

- Hurd, N. M., Varner, F. A., Caldwell, C. H., & Zimmerman, M. A. (2014). Does perceived racial discrimination predict changes in psychological distress and substance use over time? An examination among Black emerging adults. Developmental Psychology, 50(7), 1910–1918. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036438

- IBM Corp. (2017). IBM SPSS statistics for windows, version 27.0.

- Jackson, J. S., Knight, K. M., & Rafferty, J. A. (2010). Race and unhealthy behaviors: Chronic stress, the HPA axis, and physical and mental health disparities over the life course. American Journal of Public Health, 100(5), 933–939. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.143446

- Joseph, T. D., & Hirshfield, L. E. (2011). ‘Why don’t you get somebody new to do it?’ Race and cultural taxation in the academy. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 34(1), 121–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2010.496489

- Lau, N., Zhou, A. M., Zhao, X., Ng, M. Y., & Suyemoto, K. L. (2022). The invisibility of Asian American women psychologists in academia: A call to action. The Behavior Therapist, 45(3), 99–106.

- Louie, V., & Wilson-Ahlstrom, A. (2018). Moving it forward: The power of mentoring, and how universities can confront institutional barriers facing junior researchers of color. William T. Grant Foundation.

- Maestas, R., Vaquera, G. S., & Zehr, L. M. (2007). Factors impacting sense of belonging at a Hispanic-serving institution. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 6(3), 237–256. https://doi.org/10.1177/1538192707302801

- Magaña, S., Lopez, K., Aguinaga, A., & Morton, H. (2013). Access to diagnosis and treatment services among Latino children with autism spectrum disorders. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 51(3), 141–153. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-51.3.141

- McCluney, C. L., Durkee, M. I., Smith, R., Robotham, K. J., & Lee, S. S. L. (2021). To be, or not to be … Black: The effects of racial codeswitching on perceived professionalism in the workplace. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 97, 104199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2021.104199

- Merikangas, K. R., He, J. P., Burstein, M., Swendsen, J., Avenevoli, S., Case, B., Georgiades, K., Heaton, L., Swanson, S., & Olfson, M. (2011). Service utilization for lifetime mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: Results of the National Comorbidity Survey–Adolescent supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 50(1), 32–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2010.10.006

- Mirza, H. S. (2018). Racism in higher education: ‘What then, can be done? In J. Arday & H. S. Mirza (Eds.), Dismantling race in higher education: Racism, whiteness and decolonising the academy (pp. 3–23). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-60261-5_1

- Muñoz-Dunbar, R., & Stanton, A. L. (1999). Ethnic diversity in clinical psychology: Recruitment and admission practices among doctoral programs. Teaching of Psychology, 26(4), 259–263. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328023TOP260403

- Nadeem, E., Lange, J., Edge, D., Fongwa, M., Belin, T., & Miranda, J. (2007). Does stigma keep poor young immigrant and US-born black and Latina women from seeking mental health care? Psychiatric Services, 58(12), 1547–1554. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2007.58.12.1547

- Norcross, J. C., Sayette, M. A., & Martin-Wagar, C. A. (2020). Doctoral training in counseling psychology: Analyses of 20-year trends, differences across the practice-research continuum, and comparisons with clinical psychology. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 15(3), 167–175. https://doi.org/10.1037/tep0000306

- Padilla, A. M. (1994). Ethnic minority scholars, research, and mentoring: Current and future issues. Educational Researcher, 23(4), 24–27. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X023004024

- Pittman, C. T. (2012). Racial microaggressions: The narratives of African American faculty at a predominantly White university. The Journal of Negro Education, 81(1), 82–92. https://doi.org/10.7709/jnegroeducation.81.1.0082

- Poock, M. C. (2007). A shifting paradigm in the recruitment and retention of underrepresented graduate students. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 9(2), 169–181. https://doi.org/10.2190/CS.9.2.c

- Price, E. G., Gozu, A., Kern, D. E., Powe, N. R., Wand, G. S., Golden, S., & Cooper, L. A. (2005). The role of cultural diversity climate in recruitment, promotion, and retention of faculty in academic medicine. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 20(7), 565–571. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0127.x

- Price, E. G., Powe, N. R., Kern, D. E., Golden, S. H., Wand, G. S., & Cooper, L. A. (2009). Improving the diversity climate in academic medicine: Faculty perceptions as a catalyst for institutional change. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 84(1), 95. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181900f29

- Rogers, M. R., & Molina, L. E. (2006). Exemplary efforts in psychology to recruit and retain graduate students of color. The American Psychologist, 61(2), 143–156. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.61.2.143

- Ruiz, N., Edwards, K., & Lopez, M. (2021). One-third of Asian Americans fear threats, physical attacks and most say violence against them is rising. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/04/21/one-third-of-asian_americans-fear-threats-physical-attacksand-most-say-violence-against-them-isrising/

- Samano, M. L. (2007). Respecting one’s abilities, or (post) colonial tokenism?: Narrative testimonios of faculty of color working in predominantly White community colleges [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Oregon State University. https://ir.library.oregonstate.edu/concern/graduate_thesis_or_dissertations/dj52w930c?locale=en

- Settles, I. H., Buchanan, N. T., & Dotson, K. (2019). Scrutinized but not recognized: (In)visibility and hypervisibility experiences of faculty of color. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 113, 62–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.06.003

- Settles, I. H., Buchanan, N. T., & Dotson, K. (2019). Scrutinized but not recognized: (In) visibility and hypervisibility experiences of faculty of color. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 113, 62–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.06.003

- Solórzano, D., Ceja, M., & Yosso, T. (2000). Critical race theory, racial microaggressions, and campus racial climate: The experiences of African American college students. The Journal of Negro Education, 69(1–2), 60–73. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2696265

- Steketee, A., Williams, M., Valencia, B., Printz, D., & Hooper, L. M. (2021). Racial and language microaggressions in the school ecology. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(5), 1075–1098. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691621995740

- Sue, D. W., Alsaidi, S., Awad, M. N., Glaeser, E., Calle, C. Z., & Mendez, N. (2019). Disarming racial microaggressions: Microintervention strategies for targets, White allies, and bystanders. The American Psychologist, 74(1), 128. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000296

- Team, R. C. (2013). R: A language and environment for statistical computing.

- Tessler, H., Choi, M., & Kao, G. (2020). The anxiety of being Asian American: Hate crimes and negative biases during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 45(4), 636–646. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-020-09541-5

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2018). American community survey 1-year PUMS file. www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/data/pums.html

- U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (2019). Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), IPEDS Spring 2019, Human Resources component. See Digest of Education Statistics 2019, table 315.20.

- Wang, S. C., Hubbard, R. R., & Dorazio, C. (2020). Overcoming racial battle fatigue through dialogue: Voices of three counseling psychologist trainees. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 14(4), 285–292. https://doi.org/10.1037/tep0000283

- Williams, M. T. (2019). Adverse racial climates in academia: Conceptualization, interventions, and call to action. New Ideas in Psychology, 55, 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.newideapsych.2019.05.002

- Williams, M. T., Skinta, M. D., & Martin-Willett, R. (2021). After Pierce and Sue: A revised racial microaggressions taxonomy. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(5), 991–1007. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691621994247

- Willis, H. A., Gonzalez, J. C., Call, C. C., Quezada, D., Scholars for Elevating Equity and Diversity (SEED), & Galán, C. A. (2022). Culturally responsive telepsychology & mHealth interventions for racial-ethnic minoritized youth: Research gaps and future directions. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 51(6), 1053–1069. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2022.2124516

- Wilson-Ahlstrom, A., Ravindranath, R., Yohalem, N., & Tseng, V. (2017). Pay it forward: Guidance for mentoring junior scholars (updated ed.). The Forum for Youth Investment.

- Wright-Mair, R. (2020). Longing to belong: Mentoring relationships as a pathway to fostering a sense of belonging for racially minoritized faculty at predominantly white institutions. JCSCORE, 6(2), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.15763/issn.2642-2387.2020.6.2.1-31