ABSTRACT

Objective

Self-guided digital mental health interventions (DMHIs) teaching empirically supported skills (e.g. behavioral activation) have demonstrated efficacy for improving youth mental health, but we lack evidence for the complex skill of cognitive restructuring (CR).

Method

We conducted the first-ever RCT testing a CR DMHI (“Project Think”) against an active control (supportive therapy; “Project Share”) in collaboration with public schools. Pre-registered outcomes were DMHI acceptability and helpfulness post-intervention, as well as internalizing symptoms and CR skills use from baseline to seven-month follow-up, in the full sample and the subsample with elevated symptoms.

Results

Participants (N = 597; MAge = 11.99; 48% female; 68% White) rated both programs highly on acceptability and helpfulness. Both conditions were associated with significant internalizing symptom reductions across time in both samples, with no significant condition differences. CR skills use declined significantly across time for Project Share youths but held steady across time for Project Think youths in both samples; this pattern produced a significant condition difference favoring Project Think within the elevated sample at seven-month follow-up.

Conclusion

Internalizing symptoms declined comparably for Think and Share participants. Consequently, future research should examine whether encouraging youths to share their feelings produces symptom improvements, and whether a single-session, self-guided CR DMHI produces beneficial effects relative to more inert control conditions. Further, the decline in CR skills use for Project Share youths versus sustained CR use by Project Think youths raises questions about the natural time course of youths’ CR use and the impact of these DMHIs on that course. ClinicalTrials.gov Registration: NCT04806321.

Despite advances in the dissemination of child and adolescent (“youth”) psychotherapies, most youths who could benefit from mental health (MH) services do not access them (Kataoka et al., Citation2002; Kazdin & Blase, Citation2011; Kessler et al., Citation2005; Olfson et al., Citation2003), and this treatment gap (Kazdin, Citation2019) is fueled by a supply-and-demand problem: there are too few clinicians relative to the number of youths who require MH care. On the demand side, there was growing youth MH need even before the COVID-19 pandemic (Benton et al., Citation2021; Racine et al., Citation2021) – from 2016 to 2020, the prevalence of anxiety and depressive disorders in American youths aged 3–17 grew by 29% and 27%, respectively (Lebrun-Harris et al., Citation2022). During and after the pandemic, the prevalence of mental health problems among youth increased markedly, resulting in a mental health crisis whose effects on the treatment gap linger (Chavira et al., Citation2022). On the supply side, as of 2022 more than 90% of the U.S. population lived in a county where there were not enough mental health professionals to meet the demand for services (Davenport et al., Citation2023), and 47% of Americans lived in a “mental health workforce shortage area,” with some states needing up to 700 more practitioners to address additional unmet need and remove this designation (Kaiser Family Foundation, Citation2023). Further, only 4% of U.S. clinical psychologists identify as youth clinicians (American Psychological Association, Citation2021). It is therefore unsurprising that ~ 80% of adolescents experiencing mental illness will never receive care (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2022).

Many have called for the development of treatments that are scalable and cost-effective (Hollis, Citation2022; Schleider, Dobias, Sung, Mullarkey, et al., Citation2020), such as brief MH interventions that require little-to-no clinician support (Schleider & Beidas, Citation2022; Schleider, Dobias, Sung, Mullarkey, et al., Citation2020). Self-administered, single-session digital mental health interventions (DMHIs) fit this description: they require no professional oversight and are delivered in one sitting, nearly anywhere. Notably, in addition to addressing limited provider availability, DMHIs are also a promising method of overcoming other barriers to accessing MH services, such as cost and logistical issues (e.g., transportation, time constraints, and MH system complexity) that are especially burdensome among marginalized youth (Kazdin, Citation2019; Schueller et al., Citation2019; Weisz et al., Citation2013).

Single-session interventions can teach empirically supported treatment (EST) elements, and they have demonstrated benefits on youth MH. A meta-analysis of 50 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) testing single-session interventions for youth MH revealed a small-to-medium mean post-intervention effect size (Hedges g = .32; Schleider & Weisz, Citation2017). Further, several brief treatments have proven effective when delivered as non-personalized, static DMHIs (Dobias et al., Citation2021; Fitzpatrick et al., Citation2023; Osborn et al., Citation2020; Schleider, Dobias, Sung, Mullarkey, et al., Citation2020, Schleider et al., Citation2022; Schleider & Weisz, Citation2018).

High on the DMHI research agenda is assessing which therapeutic skills can be conveyed effectively in this format. While there is favorable evidence for DMHIs that teach growth mind-set (e.g., Osborn et al., Citation2020; Schleider & Weisz, Citation2018), behavioral activation (Schleider et al., Citation2022), and problem-solving skills (Fitzpatrick et al., Citation2023), it is unlikely that all elements will be well-suited to this format. Given the potential benefits of self-guided youth DMHIs, it is critical to investigate which elements can be implemented in this minimalist format to identify the boundary beyond which a more substantial approach (e.g., multiple sessions; therapist involvement) is necessary.

At least one EST element, cognitive restructuring/reappraisal (CR) (Beck, Citation1979; Clark, Citation2022), has not been tested as a self-administered DMHI against a potent control condition via RCT. CR involves changing one’s perception of the meaning or self-relevance of a situation to change its emotional impact (Gross, Citation2015; McRae et al., Citation2012). CR requires identifying unhelpful thoughts and their connections to negative emotions, evaluating whether these thoughts are true, and generating more helpful thoughts (Beck, Citation1979; Clark, Citation2022; Weisz & Bearman, Citation2020).

CR is a central component of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). While there have been several CBT DMHI trials, these DMHIs have included additional therapeutic components such as relaxation skills, problem solving, and activity scheduling (Pennant et al., Citation2015). Therefore, even in rare cases where trials have tested mediators of treatment effects (Ng et al., Citation2023), it remains unclear whether CR or other elements drive clinical improvement (Ng, DiVasto, Gonzalez et al., Citation2023).

There have been two studies evaluating CR-only DMHIs. In one study, researchers embedded three DMHIs, one of which focused on CR, into a social media site (Dobias et al., Citation2022). The study reported change in outcome measures from pre-to-immediately post-DMHI, but youths were not randomized to interventions, and the interventions were not compared to one another or to a control condition. In another study, researchers tested a language model-enabled system for walking users through CR (Sharma et al., Citation2023). While this study used a RCT design, participants were assigned only to variations of the CR intervention (e.g., with versus without psychoeducation surrounding CR), thus precluding conclusions regarding the efficacy of CR DMHIs relative to non-CR controls. Both studies represent valuable additions to the literature, but testing CR DMHIs against active control conditions via RCT remains an important task.

There are reasons to believe that CR may not lead to clinical improvement in DMHIs, and perhaps most notable among them is the fact that CR can be especially difficult to implement successfully with youths even when done over the course of several face-to-face sessions with a clinician (Kingery et al., Citation2006), in part because CR requires advanced metacognitive abilities such as identifying and scrutinizing one’s thoughts (Garber et al., Citation2016). Delivering CR in one sitting, in the absence of a skilled clinician to stimulate CR through Socratic questioning may prove more challenging still. Additionally, it seems important to evaluate the efficacy of CR in this unguided format given concerns that CR (like many other therapeutic techniques), if used incorrectly, may risk invalidating negative thoughts that are in fact valid and important (e.g., minoritized youths’ awareness of prejudice and discrimination; see Donovan, Citation2023 for a discussion of how to avoid invalidation when using CR with youth). Such challenges may be especially difficult to navigate successfully without the clinician guidance that traditional psychotherapy can provide; but if CR could be implemented successfully in a self-guided, digital format, youth access to MH support could be expanded greatly.

Thus, we tested a DMHI specifically focused on teaching CR to adolescents to help define the range of benefits. To avoid invalidating youths’ reasonable reactions to real-life stressors, we define CR with the caveat that not all negative thoughts are appropriate for restructuring (e.g., some thoughts might be more appropriately addressed via defusion (Larsson et al., Citation2016), which involves noticing thoughts and letting them come and go without responding to them), and that CR is qualitatively different from the notion that one should “think positive thoughts and everything will be OK!” (Donovan, Citation2023). We carried out a RCT testing the effects of a brief DMHI teaching youths to use CR to address thoughts that are negative and likely false (Project Think) relative to a supportive therapy DMHI (Project Share). Pre-registered aims involved evaluating intervention acceptability, comparing changes in CR skill use and changes in internalizing symptoms from baseline to seven-months post-intervention between conditions, and identifying moderators of intervention effects. We analyzed longitudinal outcomes separately for the full sample and for the subsample of participants with elevated internalizing symptoms at baseline to determine whether Project Think is most appropriate as an intervention for symptomatic youths or youths spanning a broad range of symptom severity. We hypothesized that youths would perceive Project Think as acceptable and useful, and that participants randomly assigned to Project Think would experience greater reductions in internalizing symptoms and greater increases in CR skills use compared to participants assigned to Project Share, for all participants and for the elevated subsample.

Method

This study was pre-registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT05720741). All procedures were approved by the Harvard University IRB and partner school administrators. Pre-registered analyses, statistical code, and de-identified data are publicly available (https://osf.io/r5wfs; deviations from the pre-registered plan are described in Supplement A).

School District Partnership

This study was conducted between February and October 2023 in collaboration with two suburban public-school districts in Massachusetts. The first school is in a town with a population of 30,000 and a median household income of ~$125,000; it has ~ 850 enrolled students with 24% ethnic/racial minority enrollment. The second school is in a town with a population of 21,000 and a median household income of ~$57,000; it has ~ 520 enrolled students with 40% ethnic/racial minority enrollment. Per community-engaged research guidelines (Key et al., Citation2019), study procedures were designed and implemented in partnership with key stakeholders: one teacher per school served as a “champion,” liaising between the research team and students, other teachers, families, and administrators. We minimized procedural complexity and burdensomeness by using passive (i.e., opt-out) consent procedures.

Participants

Students in grades 6–7 in the two partner schools were invited to participate. Exclusion criteria included: (i) caregiver opting their child out of the study or the child not assenting, and (ii) the child not being comfortable engaging with the English-language program. All students in our partner schools were provided with a computer/tablet to participate. 597 students (Share: 298; Think: 299) were included in the intent-to-treat sample ().

Procedures

School administrators e-mailed a passive consent form to caregivers. Nine caregivers indicated that their child should be excluded. All students who were opted out and those who refused assent completed an alternative activity selected by school personnel. Assenting students completed online questionnaires and were randomized 1:1 within Qualtrics to Project Think or Project Share; participants and the research team were blind to condition and had no influence on allocation.

Participants were invited to complete online questionnaires one-month (four-weeks), 10-weeks, and seven-months (28-weeks) post-intervention (Supplement A describes assessment time point selection). Students completed all follow-up assessments during class time to maximize response quality and completion rates. We compensated students (via Amazon gift cards) directly or donated to their school district, depending on the preferences of the school administrators.

Interventions

Project Think

Project Think (https://osf.io/qhzya/) is a 30-minute self-guided DMHI based in Qualtrics. In line with DMHIs that are effective for adolescent MH (Fitzpatrick et al., Citation2023; Osborn et al., Citation2020; Schleider, Dobias, Sung, Mullarkey, et al., Citation2020; Schleider & Weisz, Citation2018), Project Think uses engaging exercises and graphics to teach youths to identify unhelpful thoughts and entertain more helpful ones. Project Think contains background information on the relationship between thoughts, feelings, and actions, as well as an introduction to CR and an overview of which thoughts are most appropriate for this skill (i.e., thoughts that are negative and false). Project Think also provides an accessible summary of research findings in support of CR, and a step-by-step guide for CR: (i) notice when feelings change, (ii) identify the unhelpful thought that might have led to the feelings and (iii) reasons why it might not be true, and (iv) entertain more helpful thoughts. To teach users this step-by-step guide, Project Think uses branching logic in which participants are first asked to choose one of three common unhelpful thoughts (i.e., “I’m a failure,” “Nobody likes me,” or “Nothing ever goes my way”); depending on which example thought the user selects, they are directed to a vignette detailing the story of an older student who had this thought and how they used each step of CR to address it. In addition to demonstrating how CR can be used to address one of the three sample problems, Project Think asks the user to identify an unhelpful thought that they have had or might have in the future. Users can choose from the following options, or they can write in their own unhelpful thought: “I can’t do anything right,” “My friend didn’t text me back today, so they must be mad at me,” “If I don’t do well on this quiz, I’m going to fail the class,” and “I didn’t get invited to that party. I’m so unpopular!.” However, no individualized feedback is given based on the option the user selects. Additionally, building on findings indicating that “saying is believing” (Aronson, Citation1999), youths are asked to imagine that a friend is having unhelpful thoughts, like “I’ll never be as smart or fun as other people,” and use the steps they learned to help their friend. Finally, youths are asked to reflect on how they can continue practicing CR in their daily lives.

Project Share

Project Share (https://osf.io/u4axs/) matches Project Think in format and length but differs in content: Project Share uses supportive therapy principles to encourage youths to share their feelings with trusted others by explaining why sharing feelings is natural, important, and helpful, and by providing testimonials from adolescents who benefitted. Project Share is a suitable control condition because its overlap with non-directive supportive psychotherapy mirrors treatments that youth often receive in the real-world, from which many clients derive psychological benefits (Cuijpers et al., Citation2012), potentially because of common factors such as empathy and relationship building (Wampold, Citation2015). Project Share has been used in several previous trials – while it has been outperformed by experimental DMHIs in some studies (e.g., Schleider & Weisz, Citation2018), it is associated with significant within-group decreases in internalizing symptoms (Schleider et al., Citation2022), thus making it a strong comparison condition which, if outperformed by Project Think, would speak to the potency of the CR DMHI.

Outcome Measures

Behavior and Feelings Survey

The Internalizing Subscale of the Behavior and Feeling Survey (BFS; Weisz et al., Citation2020) is a six-item measure used to evaluate MH symptoms at all time points. All items are rated on a scale from 0 (not a problem) to 4 (a very big problem). Items include statements such as “I feel down or depressed” and “I feel nervous or afraid.” The BFS has been validated in a sample of youths ages 7–15, with results indicating robust factor structure, internal consistency, test-retest reliability, convergent and discriminant validity with similar measures, and utility for tracking changes in symptoms over time (Weisz et al., Citation2020). In our study, McDonald’s ωt (Citation1999)Footnote1 computed at pre-intervention, one-month follow-up, 10-week follow-up, and at seven-month follow-up was 0.94, 0.94, 0.96, and 0.94, respectively.

Emotion Regulation Questionnaire

Cognitive reappraisal

The use of CR – a putative mechanism – was assessed via the Cognitive Reappraisal Subscale of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire for Children and Adolescents (ERQ; Gullone & Taffe, Citation2012) at all time points. Participants were asked to rate the 6 items from the Cognitive Reappraisal Subscale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Items include statements such as “When I’m worried about something‚ I make myself think about it in a way that helps me feel better” and “I control my feelings about things by changing the way I think about them.” The CR Subscale of the ERQ has high internal consistency (α = .79 for Reappraisal) and 3-month test – retest reliability (r = .69), as well as convergent and discriminant validity with younger and older adults (Gross & John, Citation2003; John & Gross, Citation2004).

Expressive Suppression

The use of expressive suppression (also referred to herein as “emotional suppression” – a form of response modulation that involves inhibiting ongoing emotion-expressive behavior (Gross & John, Citation2003)) – was assessed via the Expressive Suppression Subscale of the ERQ (Gullone & Taffe, Citation2012). Participants were asked to rate the 4 items from the Cognitive Reappraisal Subscale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Items include statements such as “I keep my feelings to myself” and “When I’m feeling bad (e.g. sad‚ angry‚ or worried), I’m careful not to show it.” Like the ERQ-Reappraisal Subscale, the Suppression Subscale has high internal consistency (α = .73) and 3-month test-retest reliability (r = .69), as well as convergent and discriminant validity with younger and older adults (Gross & John, Citation2003; John & Gross, Citation2004).

McDonald’s ωt computed at pre-intervention, one-month follow-up, 10-week follow-up, and at seven-month follow-up for the full ERQ was 0.87, 0.91, 0.94, and 0.91, respectively.

Perceived Program Acceptability And Helpfulness

Perceived program acceptability and helpfulness were assessed immediately post-intervention via the Program Feedback Scale (Schleider, Dobias, Sung, Mumper, et al., Citation2020). This scale consists of 7 items (Supplement B) rated from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating greater acceptability and helpfulness. Items include statements such as “I enjoyed the activity” and “I agreed with the program’s message.” In line with prior work (Fitzpatrick et al., Citation2023; Schleider, Dobias, , Sung, Mumper, et al., Citation2020) and our pre-registration, scores greater than or equal to 3.5/5.0 were considered acceptable. McDonald’s ωt computed at post-intervention was 0.91.

Potential Covariate: Treatment Expectations

Differences between Project Think and Project Share participants’ expectancies were evaluated using an original measure of treatment expectations. This 4-item measure evaluates participants’ pre-intervention expectations regarding various aspects of their assigned intervention (e.g., “How much do you think you will like doing the online wellness activity?”; “How much do you think the online wellness activity will help you at school?”). These items were rated from 0 (not at all) to 10 (a lot). McDonald’s ωt computed at pre-intervention was 0.90.

Analysis Plan

Follow-Up Assessments

Mean response rates for follow-up assessments (ranging from 65.7% to 79.7%) were larger than those in related research (e.g., 44.1% mean response rate for online follow-up assessments across ~ 1,000 published studies; Wu et al., Citation2022). To understand the mechanism driving missingness, we used the VIM package in R (Kowarik & Templ, Citation2016). Results indicated that missingness was not related to student demographics nor was it driven by factors related to assessment characteristics (e.g., students did not discontinue participation at a particular question) or treatment condition (i.e., attrition did not differ between conditions), which we attribute in part to the fact that the intervention and assessments were brief and done in schools, during class time, as opposed to asynchronously at home. These results suggest a missing at random (MAR) pattern (Rubin, Citation1976; Van Buuren, Citation2018). Accordingly, we first created item-level mean scores to account for missingness at the item level. For generalized linear mixed effects models, the maximum likelihood implementation in the glmmTMB R package uses all available data which, in the case of MAR, leads to unbiased estimates (Brooks et al., Citation2017; Hedeker & Gibbons, Citation2006).

Model Covariates

To determine whether the conditions were balanced on demographic factors, we explored differences in baseline characteristics. No significant differences were detected between conditions for age (t = −1.30, p = .19), gender (F(595) = 2.90, p = .089), race/ethnicity (F(595) = 0.70, p = .40), income (F(589) = 0.279, p = .60), treatment expectancies (t = −0.34, p = .74), or internalizing symptoms (t = −0.47, p = .64). Accordingly, no covariates were included in the generalized linear mixed-effects models reported in text, but we did repeat the analyses while controlling for gender and age, which are both associated with study outcomes, to test the robustness of our findings. These models with age and gender as covariates are reported in Supplement E but are not discussed here given that the results for the Condition*Time interactions do not diverge from the original models without these covariates.

Elevated Subsample

In line with standardized measures of youth MH (e.g., Achenbach, Citation2001), elevated baseline internalizing symptoms were defined as one SD above the sample mean on the BFS.

Generalized Linear Mixed-Effects Models

To examine the effects of Project Think on trajectories of internalizing symptoms and CR tendencies – within the full sample and the elevated subsample – we implemented beta-distributed generalized linear mixed effects models (GLMMs) via the glmmTMB package in R (Brooks et al., Citation2017). In each model, the outcome was predicted by a Condition*Time interaction (in the case of the exploratory analyses, Condition*Time*Moderator or Time*Moderator(s)). A random intercept was specified to account for the nested data structure (i.e., measurement occasions nested within adolescents within schools).

We used beta-distributed GLMMs to account for the fact that the distributions of our outcome variables caused a violation of the normality assumption when implementing linear mixed-effects models (Smithson & Verkuilen, Citation2006; Stroup, Citation2013). Because our data were right-skewed with natural boundaries at scale endpoints, we transformed the data to a (0,1) scale (Supplement A describes our approach in more detail) to implement beta-distributed GLMMs (using the default logit link function).Footnote2 Thus, all effect sizes reported herein can be interpreted as odds ratios (ORs): the estimated increase in the odds of the outcome (e.g., internalizing symptoms) per unit increase in the value of the exposure (i.e., study condition; Szumilas, Citation2010).

Independent Samples T-Tests

To test perceived acceptability and helpfulness of the DMHIs immediately post-intervention, we used independent samples t-tests via the t.test function in the stats R package (R Core Team, Citation2023), comparing the means of each item on the Program Feedback Scale across conditions, as well as the aggregated item-level mean of the overall scale.

Follow-Up Assessments Completion Rates

We used Z tests of differential proportions to evaluate whether the proportion of participants who failed to respond to follow-up surveys differed significantly between conditions.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Participant characteristics are shown in Supplement C, and average scores on outcomes across time are shown in Supplement D. Participants were 11–13 years old (M = 11.99, SD = 0.69), with a plurality identifying as female (48.4%; 45.2% male; 4.8% gender diverse). Most participants self-reported a middle-class background (81.6%) or a working class (12.6%) background (Hughes et al., Citation2016). Participants were predominantly White (68.0%) or held multiple ethnic/racial identities (10.4%; 5.5% Hispanic or Latinx; 4.2% Black or African American; 4.0% Asian; 2.0% Middle Eastern or North African; 2.5% other race or ethnicity).

Elevated Subsample

98 students (50.0% [49 students] in Project Think and 50.0% [49 students] in Project Share) reported elevated internalizing symptoms (baseline BFS mean item-level score greater than 2.06).

Follow-Up Assessment Completion Rates

Z tests of differential proportions yielded no significant differences between conditions in assessment completion rates at one-month (attrition rates of 20.4% in Think and 20.5% in Share; p = .99), 10-weeks (21.7% in Think and 22.8% in Share; p = .83), or seven-months (37.1% in Think and 36.6% in Share; p = .96) follow-up.

Primary Analyses

Aim 1: Intervention Acceptability and Helpfulness

Students rated both interventions as acceptable and useful, per mean item-level ratings of at least 3.5 out of 5.0 (Supplement B). Independent samples t-tests revealed that students who completed Project Think reported agreeing with their activity’s message significantly more than students who completed Project Share (t = 2.00, p = .046); there were no significant condition differences on other item scores or on mean item-level scores aggregated across items, which is consistent with prior studies using Project Share as a comparison condition (Dobias et al., Citation2021).

Aim 2: Effect on Internalizing Symptoms within Full Sample

Students in both conditions reported significant reductions in internalizing symptoms across the study period, with within-condition exploratory GLMM analyses revealing significant decreases in internalizing symptoms among participants in both Project Think (χ2 (3) = 28.41, p = .000) and Project Share (χ2 (3) = 22.21, p = .000) over time (Supplement E). Contrary to our hypothesis, students who completed Project Think did not report significantly greater reductions in internalizing symptoms than students assigned to Project Share at any follow-up assessment per our GLMM with a Condition*Time interaction ( and ). We used the Anova() function from the car package (Fox & Weisberg, Citation2019) as an omnibus test of the effect of Condition*Time on internalizing symptoms, which revealed a non-significant overall interaction effect (χ2 (3) = 3.58, p = .31).

Figure 2. Results from beta-distributed generalized linear mixed-effects model with the full sample and youth internalizing symptoms as the outcome. Note. The dotted line represents model-estimated mean BFS internalizing scores among adolescents in Project Share, and the solid line represents model-estimated mean BFS internalizing scores among adolescents in Project Think, across the 7-month study period.

Table 1. Results from beta-distributed generalized linear mixed-effects model with the full sample and youth internalizing symptoms as the outcome.

Aim 3: Effect on Internalizing Symptoms within Elevated Sample

Students in both conditions in the elevated sample reported significant reductions in internalizing symptoms across the seven-month study period, with within-condition exploratory GLMM analyses revealing significant declines in internalizing symptoms among participants with elevated levels of baseline internalizing symptoms in both Project Think (χ2 (3) = 18.46, p = .000) and Project Share (χ2 (3) = 21.63, p = .000) over time (Supplement E). Contrary to our hypothesis, Project Think participants in the elevated sample did not report significantly greater reductions in internalizing symptoms, relative to those assigned to Project Share, at any follow-up assessment ( and ). We used the Anova() function as an omnibus test of the effect of Condition*Time on internalizing symptoms in the elevated sample, which revealed a non-significant overall interaction effect (χ2 (3) = 2.09, p = .55).

Figure 3. Results from beta-distributed generalized linear mixed-effects model with the elevated subsample and youth internalizing symptoms as the outcome. Note. The dotted line represents model-estimated mean BFS internalizing scores among adolescents in Project Share, and the solid line represents model-estimated mean BFS internalizing scores among adolescents in Project Think, across the 7-month study period.

Table 2. Results from beta-distributed generalized linear mixed-effects model with the elevated subsample and youth internalizing symptoms as the outcome.

Secondary Analyses

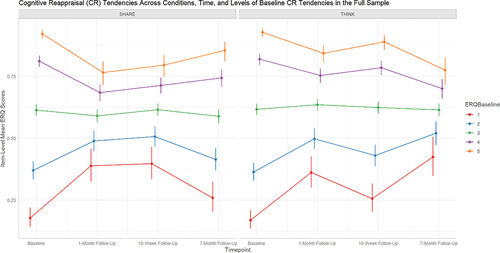

Aim 4: Effect on Putative Mechanism (CR Skills Use) within Full Sample

Students in Project Think did not evince a significant change in CR tendencies over the course of the study period, but students in Project Share reported a significant decrease in CR tendencies at the seven-month follow-up assessment: within-condition exploratory GLMM analyses revealed no significant change in CR skills use among participants in Project Think over time (χ2 (3) = 1.17, p = .76), whereas we detected an overall significant decrease in CR skills use over time among participants in Project Share (χ2 (3) = 8.29, p = .04; Supplement E). Contrary to our hypothesis, there were no significant differences in CR tendencies between students who received Project Think relative to Project Share at any follow-up assessment ( and ). We used the Anova() function as an omnibus test of the effect of Condition*Time on CR tendencies, which revealed a non-significant overall interaction effect (χ2 (3) = 3.59, p = .31).

Figure 4. Results from beta-distributed generalized linear mixed-effects model with the full sample and cognitive reappraisal tendencies as the outcome. Note. The dotted line represents model-estimated mean CR scores among adolescents in Project Share, and the solid line represents model-estimated mean CR scores among adolescents in Project Think, across the 7-month study period.

Table 3. Results from beta-distributed generalized linear mixed-effects model with the full sample and cognitive reappraisal tendencies as the outcome.

Aim 5: Effect on Putative Mechanism (CR Skills Use) within Elevated Sample

In the elevated sample, there was a significant difference in CR tendencies favoring students in Project Think relative to Project Share at the seven-month follow-up assessment per our GLMM with a Condition*Time interaction (OR = 1.71, 95%CI [1.05, 2.79]; and ). However, this significant effect was driven by CR reductions across time for students who received Project Share, as opposed to CR increases for students who received Project Think: within-condition exploratory GLMM analyses revealed a non-significant change in CR skills use among participants with elevated levels of baseline internalizing symptoms in Project Think (χ2 (3) = 0.75, p = .86), but significant declines in CR skills use in Project Share (χ2 (3) = 8.01, p = .046) over time (Supplement E). We used the Anova() function as an omnibus test of the Condition*Time effect on CR tendencies in the elevated subsample, which revealed a non-significant overall interaction effect (χ2 (3) = 6.13, p = .11).

Figure 5. Results from beta-distributed generalized linear mixed-effects model with the elevated subsample and cognitive reappraisal tendencies as the outcome. Note. The dotted line represents model-estimated mean CR scores among adolescents in Project Share, and the solid line represents model-estimated mean CR scores among adolescents in Project Think, across the 7-month study period.

Table 4. Results from beta-distributed generalized linear mixed-effects model with the elevated subsample and cognitive reappraisal tendencies as the outcome.

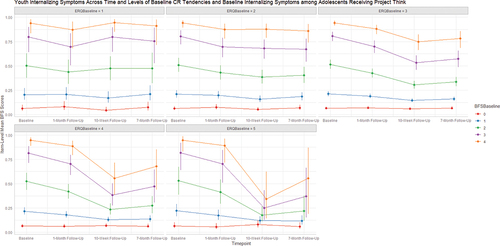

Exploratory Analyses

In line with our pre-registered plan, we conducted analyses to determine whether Project Think might be differentially effective for students of varying baseline characteristics and to further explain the findings noted above. The results of these analyses are reported below (Aim 6a: and ; Aim 6b: and ) and in Supplement E.

Figure 6. Results from beta-distributed generalized linear mixed-effects model with cognitive reappraisal tendencies, moderated by baseline cognitive reappraisal tendencies, as the outcome. Note. The lines represent model-estimated mean CR score trajectories among adolescents in Project Share (left panel) and Project Think (right panel); the orange line represents the trajectory of CR scores across time for adolescents with the highest baseline CR scores, followed by the purple line, green line, blue line, and the red line, the latter of which represents adolescents with the lowest CR scores at baseline. This plot demonstrates a significant interaction effect at the seven-month follow-up time point (OR = 0.68, p < .001) such that students with lower baseline CR scores (relative to higher baseline CR scores) evinced higher CR scores at the seven-month follow-up assessment if they had completed Project Think than if they had completed Project Share.

Figure 7. Results from beta-distributed generalized linear mixed-effects model with youth internalizing symptoms, moderated by baseline cognitive reappraisal tendencies and baseline youth internalizing symptoms, as the outcome. Note. The lines represent modelestimated mean BFS internalizing score trajectories among adolescents in the Project Think condition; the orange lines in each panel represent the trajectory of BFS scores across time for adolescents with the highest baseline BFS scores, followed by the purple line, green line, blue line, and the red line, the latter of which represents adolescents with the lowest BFS scores at baseline. Moving from left to right along the top set of panels, the first panel (“ERQBaseline = 1”) represents the adolescents with the lowest CR scores at baseline, followed by “ERQBaseline = 2,” “ERQBaseline = 3,” and “ERQBaseline = 5,” the latter of which represents adolescents with the highest ERQ scores at baseline. This plot demonstrates a significant interaction effect at the 10-week follow-up time point (OR = 0.80, p = .002): students in the Project Think condition with high baseline CR scores coupled with high baseline BFS-Internalizing scores demonstrated significantly reduced BFS-internalizing scores at follow-up relative to students with low baseline CR scores and low baseline BFS-internalizing scores.

Table 5. Results from beta-distributed generalized linear mixed-effects model with cognitive reappraisal tendencies, moderated by baseline cognitive reappraisal tendencies, as the outcome.

Table 6. Results from beta-distributed generalized linear mixed-effects model with youth internalizing symptoms, moderated by baseline cognitive reappraisal tendencies and baseline youth internalizing symptoms, as the outcome.

Aim 6: Examining Candidate Moderators

Aim 6a: Effect of Baseline CR Tendencies on Changes in CR

A CR DMHI might be expected to improve CR most in youths who report low CR use at baseline. We investigated whether receiving Project Think, relative to Project Share, improved CR differently based on students’ baseline CR scores. To find out, we implemented a beta-distributed GLMM in which CR score was predicted by the interaction of assessment time point, condition (Think versus Share), and baseline CR score. As shown in and , we found a significant interaction effect at the seven-month follow-up time point (OR = 0.68, 95%CI [0.56, 0.83]), such that students with lower baseline CR scores (relative to higher baseline CR scores) evinced higher CR scores at the seven-month follow-up assessment if they had received Project Think than if they received Project Share.

Aim 6b: Effect of Baseline Internalizing Symptoms and CR Tendencies on Changes in Internalizing Symptoms

Building on the findings of Aims 5 and 6a, we investigated whether students who were theoretically most in need of intervention – those characterized by low baseline CR tendencies coupled with high baseline internalizing symptoms – evinced differential rates of improvement in internalizing symptoms. We implemented a beta-distributed GLMM in which BFS was predicted by the interaction of follow-up assessment time point, baseline CR score, and baseline BFS score, among students who received Project Think. As shown in and , we found a significant interaction effect at the 10-week follow-up time point (OR = 0.80, p = .002): students in Project Think with higher baseline CR scores (as opposed to lower CR scores, as in Aim 6a) coupled with high baseline internalizing scores demonstrated significantly reduced internalizing scores at follow-up relative to students with low baseline CR scores and/or low baseline internalizing scores.

Aim 7: Intervention Effect on Emotional Suppression

Finally, to attempt to better explain the lack of a condition difference in trajectories of CR usage for the full sample, as well as the relative decrease in CR usage among Project Share participants (compared to Project Think participants) in the elevated subsample, we examined the effect of each program on emotional suppression, the inverse of the mechanism hypothesized to account for change in Project Share (i.e., emotional expression). We implemented two beta-distributed GLMMs (one for the full sample and one for the elevated subsample) in which the Expressive Suppression sub-score of the ERQ was predicted by the interaction of follow-up assessment time point and condition (Think vs Share). As shown in Supplement E, although we did not detect any significant differences between conditions across time in the elevated subsample (all Condition*Time p-values > .14), in the full sample, we found a significant interaction effect at the 7-month follow-up time point, such that students who received Project Share reported less emotional suppression than students assigned to Project Think (OR = 1.21; p = .035). We used the Anova() function as an omnibus test of the effect of Condition*Time on suppression tendencies, which revealed a non-significant overall interaction effect (χ2 (3) = 6.22, p = .10).

Discussion

In this RCT, we tested the effects of a single-session DMHI (Project Think) – relative to a matched supportive therapy control program (Project Share) – on self-reported youth internalizing symptoms and use of CR as an emotion regulation strategy. We implemented these interventions remotely during class time, without the involvement of a clinician, thereby testing intervention effects under real-world school conditions. To our knowledge, this is the first RCT testing the effects of a self-guided youth CR DMHI relative to an active control condition; this is notable because multiple DMHIs tested in RCTs include CR as a therapeutic component (Erhardt et al., Citation2022; Morello et al., Citation2023), but no RCTs have established whether CR is a necessary or sufficient ingredient in these interventions, or whether CR DMHIs produce clinical improvements above and beyond other therapeutic interventions (e.g., Sharma et al., Citation2023). Thus, it is possible that other elements in CBT DMHIs (e.g., problem solving, behavioral activation) drive the positive effects reported in published RCTs; testing the effects of a self-guided DMHI that teaches CR skills in the absence of other evidence-based elements can determine whether CR can be delivered effectively in this format.

In line with our first hypothesis, we found that participants in both study conditions perceived their assigned intervention as acceptable and helpful (Aim 1), but youths who received Project Think (vs. Share) gave significantly higher ratings on the item “I agree with the program’s message.” Project Think’s message is that some thoughts are unhelpful and that these thoughts can be altered to improve one’s mood; Project Share’s message is that it is helpful to identify emotions and share them with trusted people in one’s life (e.g., parents). This difference between conditions suggests that participants attended to the intervention content, and that they viewed CR as a more plausible approach. Agreement with a DMHI’s message may strengthen motivation to try the skills, thus contributing to dissemination and uptake (Sekhon et al., Citation2017).

We also hypothesized that Project Think participants would report reduced internalizing symptoms and increased use of CR over time compared to Project Share participants, within the full sample and within the elevated symptom subsample. While participants in both conditions reported significantly decreased internalizing symptoms over the course of the study, we found no significant difference between conditions for either sample (Aim 2 and Aim 3). There are several possible explanations for the significant decline in symptoms in both conditions, with no condition difference. One explanation is that Project Share is more potent than anticipated. Although Project Share was designed as a supportive therapy control condition and has been outperformed by active treatments in two studies (e.g., Schleider & Weisz, Citation2018; Schleider et al., Citation2022), recent research suggests beneficial effects of Project Share (Dobias et al., Citation2021; Hollinsaid et al., CitationIn preparation). For example, a RCT testing a DMHI for adolescent self-injurious thoughts and behaviors found a positive within-group effect for Project Share on the primary outcome of post-intervention NSSI risk (Dobias et al., Citation2021). Additionally, Project Share has demonstrated especially large effects for LGBTQ+ youth living in high-stigma contexts (Hollinsaid et al., CitationIn preparation). A large body of literature supports the idea that sharing one’s emotions can improve youth MH (Gonsalves et al., Citation2023), and this work has informed interventions that focus explicitly on emotion expression (e.g., expressive writing; Travagin et al., Citation2015). Further, upon querying a sample of depressed adolescents about the perceived effectiveness of coping strategies that adolescents utilize spontaneously, Ng et al. (Citation2016) found that talking with supportive peers and family members was ranked second out of 20 evidence-based practice elements. Although the effectiveness of disclosing one’s emotions on MH outcomes depends on the response received (e.g., validation versus dismissal; Gonsalves et al., Citation2023), the array of evidence suggests the possibility that Project Share may produce substantial benefits.

It is also possible that Project Think may have been less effective than anticipated. Although the single-session behavioral activation and growth mind-set interventions that outperformed Project Share in previous trials (Schleider & Weisz, Citation2018; Schleider et al., Citation2022) resemble Project Think in format, length, and relatively static style, with only minimal branching logic to customize youths’ experiences with the intervention, it is possible that the former interventions are more amenable to this format than CR. This may, in turn, explain the finding that Project Think did not outperform Project Share on internalizing outcomes over time, unlike the behavioral activation and growth mind-set interventions. Whereas CR is relatively complex, typically involving back-and-forth Socratic dialogue between the clinician and client, behavioral activation and growth mind-set interventions may be more straightforward to implement without the guidance of a clinician. For example, while behavioral activation and growth mind-set have relatively simple messages (e.g., “I should do activities I typically enjoy, even if I’m not sure that I’ll enjoy them” and “I may not know how to do this now, but with effort, I can learn,” respectively) and relatively simple steps (i.e., plan time for – and reduce barriers to – doing enjoyable activities, and remind oneself that negative things in one’s life can change if one makes an effort to adjust their behavior, respectively), CR might be harder to learn, internalize, and implement in daily life on one’s own. CR requires identifying one’s own specific unhelpful thoughts and generating reasons why those thoughts may not be true, which might be especially difficult for youths who are not adept at introspection or who struggle to differentiate their automatic thoughts and perceptions from reality. Further, it might not always be clear which thoughts are appropriate for CR and which require external intervention from an adult; for example, a child might reasonably struggle with the decision to restructure negative thoughts that result from being bullied, tell an adult that they are being bullied, or do both. Finally, CR may not produce momentary relief from negative emotions to the same extent, or as quickly as, behavioral activation or growth mind-set, both of which directly prompt changes in behavior and self-cognitions that may cause more rapid improvement in one’s daily life that can be self-reinforcing. If CR were to provide less immediate relief, or less immediate evidence that it is helpful, youths might be less likely to continue to use this skill; this may be the case if youth are misapplying CR when they first use it following the intervention, which would be especially likely if they are not able to learn it correctly on their own, during the intervention.

In the full sample and the elevated symptom subsample, the use of CR strategies declined significantly across time for Project Share youths, but held steady for Project Think youths, with significantly more CR strategy use by Think youths than Share youths in the symptomatic group at the final assessment point (Aim 5). Although this trend aligns with other DMHI RCTs reporting increased intervention effects over time (e.g., Schleider & Weisz, Citation2018) – especially for symptomatic youth (Fitzpatrick et al., Citation2023) – the elevated subsample effect was driven by reductions in CR tendencies in the Project Share condition as opposed to increases in CR tendencies in the Project Think condition. We cannot know what life experiences these students may have encountered during the trial, but it may be that for students with elevated internalizing symptoms at baseline, Project Think buffered against reductions in CR use that might otherwise have been instigated by challenges of middle school life, perhaps because Project Think students felt competent enough in using CR that they continued to use it whereas the Project Share students did not. However, it might also be the case that youth who received Project Think used CR more often, but not necessarily correctly or successfully, given the concerns about CR requiring more scaffolding than other strategies such as behavioral activation and growth mind-set. It is also possible that Project Share provided a coping approach that reduced the need for CR; if youths were sharing their feelings with trusted peers and family members, and were met with helpful advice or active listening, CR might have been less necessary, and invoked less often over time. Consistent with this explanation, we found a significant condition difference in emotional suppression at the final follow-up time point, in which Share participants reported less suppression than Think participants in the full sample. Assuming that emotional suppression, as operationalized by the ERQ-Expressive Suppression Subscale (e.g., “I keep my feelings to myself”), taps into the inverse of the mechanism that might account for symptom improvements in Project Share (i.e., emotional expression), this finding suggests that it was not simply that Project Share participants discontinued CR usage, but also that they replaced the strategy with another, namely expressing their emotions to others.

To investigate which characteristics of adolescents may boost the benefits conferred by Project Think, we conducted exploratory analyses examining the effects of putative moderators. The results of these analyses can be interpreted through the lens of compensation and capitalization models of treatment personalization, whereby treatments are matched either to clients’ relative strengths (i.e., capitalization) or relative deficits (i.e., compensation [Cheavens et al., Citation2012]). We found that Project Think (vs. Project Share) produced the largest increases in CR tendencies among students who reported low CR tendencies at baseline (i.e., compensation [Aim 6a]), which might suggest that those who use CR strategies least have the most to gain from learning such strategies. This finding, combined with the results of Aim 5, prompted us to investigate whether the students who were theoretically most in need of intervention – those characterized by low baseline CR tendencies coupled with high baseline internalizing symptoms – evinced differential rates of improvement in internalizing symptoms. We found that Project Think students with high baseline CR skills use (i.e., capitalization) coupled with high baseline internalizing symptoms demonstrated significantly reduced internalizing symptoms at the 10-week follow-up relative to students with low baseline CR skills use and/or low baseline internalizing symptoms (Aim 6b). Thus, Project Think appears to benefit youth by compensating for preexisting weaknesses and by capitalizing on preexisting strengths.

The findings that (a) Project Think produced the largest positive effects on CR tendencies among students who reported low CR use at baseline, and (b) students in the Project Think condition with high baseline CR tendencies scores coupled with elevated baseline internalizing symptoms demonstrated significantly reduced internalizing symptoms at follow-up, might be interpreted as follows: whereas (a) might reflect a “floor effect” whereby those with the lowest CR tendencies at baseline are unaware of CR skills and therefore have the most room for increases in CR skills use (i.e., compensation), (b) might indicate that adolescents who frequently used CR prior to receiving Project Think, but without having been taught how to use it effectively to reduce internalizing symptoms, benefit the most from efforts to capitalize on this strength by being taught procedures that make CR most effective. Perhaps adolescents who frequently used CR strategies to regulate their emotions prior to receiving Project Think, and were still symptomatic at baseline, were those who were likely to use CR strategies more frequently and to greater effect after receiving Project Think, which in turn improved their MH. Overall, the benefits of Project Think appear to be most pronounced among those with minimal proclivity for CR initially (i.e., they begin to use CR more frequently after receiving the intervention, presumably because they improved their restructuring skills or learned CR as a new technique altogether), or among those who initially use CR frequently but nonetheless experience elevated internalizing symptoms (i.e., they were attempting to address their symptoms through CR but needed to be taught how to restructure more effectively), respectively. This possibility warrants testing in future research building on efforts to find the best fit between interventions and the youths who are most likely to benefit (Ahuvia et al., Citation2023).

Limitations

Our findings should be considered alongside certain limitations. First, most of the sample was White and middle-class, and thus we were under-powered to test these demographic characteristics as moderators of treatment effects. Although the proportion of racial/ethnic minority participants in this sample (30%) aligns with the proportions of minority students in the schools from which this sample is drawn (24% in one school, 40% in the other), it is nonetheless a limitation of this study that we were unable to confirm whether the theoretical benefits of DMHIs for minority youth (Ramos & Chavira, Citation2022) are being realized empirically. Future research should seek out more diverse samples to determine whether results differ for non-White, non-middle-class youth (McDanal et al., Citation2024).

Second, our DMHI was relatively static, without many opportunities for adolescents to personalize their experience, and without the kind of Socratic dialogue therapists use to stimulate CR. Although we used branching logic to teach CR skills in the context of adolescents’ chosen maladaptive thought, the digital format limited the number of options youths could choose from, and the program could not provide the kind of personalized feedback that would be possible in face-to-face therapy. Relatedly, our measure of CR skills use assessed frequency (Gullone & Taffe, Citation2012), not fidelity. Research on CR in a digital context could be improved by assessing effective CR skills use, perhaps using behavioral assessments in which youths practice restructuring sample cognitions (e.g., McRae et al., Citation2012).

Third, the differences detected in Aim 5, and exploratory Aim 6a and Aim 6b, were only significant at one follow-up time point, therefore necessitating replication to determine whether these differences reflect effects that emerged primarily due to intervention content interacting with life events, as is sometimes seen in DMHI research (e.g., Fitzpatrick et al., Citation2023; Schleider & Weisz, Citation2018).

Finally, we did not use a multi-informant approach to assessing outcomes (e.g., querying teachers and caregivers about youth participants) given practical limitations and our desire to minimize the burden of the study procedures. Because we only assessed students’ perceptions of their own internalizing symptoms and use of CR, we were not able to determine whether outcomes might be different for other informants’ perceptions of the youths. This is an especially noteworthy limitation in the context of assessing internalizing symptoms in youth because treatment outcomes for anxiety and depression vary across informants (De Los Reyes et al., Citation2015, Citation2019; Weisz et al., Citation2017), and the use of additional structurally different informants can facilitate probing contextual differences in treatment response (De Los Reyes et al., Citation2011, Citation2013, Citation2019, Citation2023).

Future Directions

We hope that this work will stimulate and inform future DMHI research, and we therefore suggest several future directions that seem particularly important. First, it is imperative that DMHI trials seek out diverse samples to determine whether the putative benefits of such interventions (e.g., lower cost and reduced need for transportation to and from a therapist’s office), especially for marginalized youth, are observed empirically, to avoid inadvertently perpetuating existing disparities or creating new ones (Ramos et al., Citation2021).

Second, as the number of RCTs testing individual therapy components delivered via DMHI grows, it will be possible, and desirable, to synthesize findings using network meta-analysis, to determine the relative effects of various components (Rouse et al., Citation2017). In addition, it may be especially efficient to conduct micro-RCTs in which several therapy components are compared against one another at various decision points, and a proximal outcome measure is obtained each time; this process allows for a sequence of analyses that build evidence for decision rules and personalized intervention recommendations (Klasnja et al., Citation2015; Leijten et al., Citation2021). This method may be especially appropriate for DMHI trials given that digital MH interventions can be easily disseminated many times in a relatively short time frame via mobile devices (Bidargaddi et al., Citation2020).

Third, given the static nature of Project Think (like other DMHIs), it is important to test novel methods of digital CR delivery. For example, CR strategies might be taught via virtual reality to simulate real-world situations in which unhelpful thoughts may emerge (e.g., Kitson et al., Citation2023; Theodorou et al., Citation2023). Teaching strategies via single-session DMHI could also be complemented by ecological momentary intervention – digital prompts to use CR skills in everyday life – to reinforce CR skills by providing repeated opportunities and encouragement to practice (Wang & Miller, Citation2020). Strategies might also be taught and practiced via just-in-time adaptive intervention (JITAI) functionality that deploys prompts to use skills when youths are predicted to need them most (Balaskas et al., Citation2021). Further, CR strategies might be supported by large language models to provide opportunities to practice reframing unhelpful thoughts with human-supervised feedback from chatbots (e.g., Sharma et al., Citation2023). Overall, perhaps thoughtful use of recent and emerging technology can boost the effectiveness of CR training. Alternatively, it is possible that effective CR training requires such individual tailoring and nuance that interaction with a therapist will be required, at least for some adolescents; further exploration of DMHI strategies may help determine whether that is the case, and such exploration could profit from consultation with adolescents, whose input might usefully inform intervention design (Doherty et al., Citation2010).

Finally, it is worth continuing to evaluate Project Share, given that it may have beneficial effects on youth MH. Because the benefits of sharing feelings are context dependent (Gonsalvez et al., Citation2023), future research should incorporate data on contextual factors to determine whether facets of one’s environment moderate intervention effects. Indeed, the congruence between intervention content and cultural norms affects intervention efficacy in some cases (e.g., growth mind-set interventions, which are most effective when peer norms align with intervention messaging Yeager et al., Citation2019). For example, it is plausible that youths living in contexts where emotional expression is valued will derive more benefit from sharing feelings than youths who do their sharing in less supportive contexts or with less supportive others (Hollinsaid et al., Citation2023; Vijayakumar & Pfeifer, Citation2020). It is possible that CR is effective and that sharing feelings is effective, as well, given appropriate contexts and confidants; future work can determine whether our “control” condition is more aptly characterized as an intervention. We may all be wise to remain open to a range of potentially helpful coping strategies, to avoid overlooking those that confer surprising benefits.

Conclusion

We found that a DMHI teaching CR and a DMHI teaching youth to share feelings were both associated with significant declines in internalizing symptoms, but with no difference between conditions. Further, we identified moderators of intervention effects suggesting that CR DMHIs may be differentially effective depending on adolescents’ characteristics. DMHIs found to be effective and easily implemented in school settings may hold promise for improving adolescent MH, but more work is needed to determine which components are effective for the largest number of adolescents, which components confer the greatest benefits to whom, and whether some skills are so difficult to convey digitally that live interaction with a therapist will be required for effective implementation.

Supplement.docx

Download MS Word (391.7 KB)Acknowledgments

We express sincere gratitude for our school partners, including Kerri Ciulla, Jinnee Strus, John Crocker, and the students who made this project possible.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data Availability Statement

The data reported in this manuscript have not been published previously. This study was pre-registered on ClinicalTrials.gov and Open Science Framework (OSF), and the data and reproducible statistical code are available on OSF.

Supplementary Data

Supplemental material for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2024.2384026

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 As recommended by experts (e.g., Revelle & Zinbarg, Citation2009), we used McDonald’s ωt as our reliability coefficient given that Cronbach’s α has been criticized consistently (e.g., Sijtsma, Citation2009).

2 Given the need to use beta-distributed GLMMs, we were unable to provide a mediation test evaluating whether the continued use of CR in Project Think (versus Project Share) accounted for later reductions in internalizing symptoms, because no statistical computing package that is currently available can accommodate a multi-level, longitudinal mediation model with non-normally distributed data. If we were to ignore the distributional assumptions of the mediation test, not only would the model not fit the data well, but this would be inconsistent with the approach deemed necessary for our other pre-registered analyses.

References

- Achenbach, T. M. (2001). Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles: An integrated system of multi-informant assessment. ASEBA.

- Ahuvia, I. L., Mullarkey, M. C., Sung, J. Y., Fox, K. R., & Schleider, J. L. (2023). Evaluating a treatment selection approach for online single-session interventions for adolescent depression. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 64(12), 1679–1688. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13822

- American Psychological Association. (2021). Children’s mental health is in crisis. Retrieved December 22, 2023, from https://www.apa.org/monitor/2022/01/special-childrens-mental-health

- Aronson, E. (1999). The power of self-persuasion. The American Psychologist, 54(11), 875–884. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0088188

- Balaskas, A., Schueller, S. M., Cox, A. L., Doherty, G., & Myers, B. (2021). Ecological momentary interventions for mental health: A scoping review. PLOS ONE, 16(3), e0248152. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248152

- Beck, A. T. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. Guilford Press.

- Benton, T. D., Boyd, R. C., & Njoroge, W. F. M. (2021). Addressing the global crisis of child and adolescent mental health. JAMA Pediatrics, 175(11), 1108–1110. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2479

- Bidargaddi, N., Schrader, G., Klasnja, P., Licinio, J., & Murphy, S. (2020). Designing m-health interventions for precision mental health support. Translational Psychiatry, 10(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-020-00895-2

- Brooks, M., Bolker, B., Kristensen, K., Maechler, M., Magnusson, A., McGillycuddy, M., Skaug, H., Nielsen, A., Berg, C., van Bentham, K., Sadat, N., Lüdecke, D., Lenth, R., O’Brien, J., Geyer, C. J., Jagan, M., Wiernik, B., & Stouffer, D. B. (2017). GlmmTMB: Generalized linear mixed models using template Model Builder (1.1.8) [Computer software]. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/glmmTMB/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, November 28). Improving access to Children’s mental health care. https://www.cdc.gov/childrensmentalhealth/access.html

- Chavira, D. A., Ponting, C., & Ramos, G. (2022). The impact of COVID-19 on child and adolescent mental health and treatment considerations. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 157, 104169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2022.104169

- Cheavens, J. S., Strunk, D. R., Lazarus, S. A., & Goldstein, L. A. (2012). The compensation and capitalization models: A test of two approaches to individualizing the treatment of depression. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50(11), 699–706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2012.08.002

- Clark, D. A. (2022). Cognitive reappraisal. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 29(3), 564–566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2022.02.018

- Cuijpers, P., Driessen, E., Hollon, S. D., van Oppen, P., Barth, J., & Andersson, G. (2012). The efficacy of non-directive supportive therapy for adult depression: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 32(4), 280–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.01.003

- Davenport, S., Darby, B., Gray, T., & Spear, C. (2023). Access across America: State-by-state insights into the accessibility of care for mental health and substance use disorders. Milliman, Inc. https://www.milliman.com/-/media/milliman/pdfs/2023-articles/12-12-23_milliman-report-access-across-america.ashx

- De Los Reyes, A., Augenstein, T. M., Wang, M., Thomas, S. A., Drabick, D. A. G., Burgers, D., & Rabinowitz, J. (2015). The validity of the multi-informant approach to assessing child and adolescent mental health. Psychological Bulletin, 141(4), 858–900. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038498

- De Los Reyes, A., Cook, C. R., Gresham, F. M., Makol, B. A., & Wang, M. (2019). Informant discrepancies in assessments of psychosocial functioning in school-based services and research: Review and directions for future research. Journal of School Psychology, 74, 74–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2019.05.005

- De Los Reyes, A., Kundey, S. M. A., & Wang, M. (2011). The end of the primary outcome measure: A research agenda for constructing its replacement. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(5), 829–838. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.03.011

- De Los Reyes, A., Thomas, S. A., Goodman, K. L., & Kundey, S. M. A. (2013). Principles underlying the use of multiple informants’ reports. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9, 123–149. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185617

- De Los Reyes, A., Wang, M., Lerner, M. D., Makol, B. A., Fitzpatrick, O., & Weisz, J. R. (2023). The operations triad model and youth mental health assessments: Catalyzing a paradigm shift in measurement validation. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 52(1), 19–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2022.2111684

- Dobias, M. L., Morris, R. R., & Schleider, J. L. (2022). Single-session interventions embedded within Tumblr: Acceptability, feasibility, and utility study. JMIR Formative Research, 6(7), e39004. https://doi.org/10.2196/39004

- Dobias, M. L., Schleider, J. L., Jans, L., & Fox, K. R. (2021). An online, single-session intervention for adolescent self-injurious thoughts and behaviors: Results from a randomized trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 147, 103983. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2021.103983

- Doherty, G., Coyle, D., & Matthews, M. (2010). Design and evaluation guidelines for mental health technologies. Interacting with Computers, 22(4), 243–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intcom.2010.02.006

- Donovan, C. L. (2023). Cognitive restructuring. In L. J. Farrell, R. C. Murrihy, & C. A. Essau (Eds.), Handbook of child and adolescent psychology treatment modules (pp. 89–107). Academic Press.

- Erhardt, D., Bunyi, J., Dodge-Rice, Z., Neary, M., & Schueller, S. M. (2022). Digitized thought records: A practitioner-focused review of cognitive restructuring apps. The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, 15, e39. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1754470X22000320

- Fitzpatrick, O. M., Schleider, J. L., Mair, P., Carson, A., Harisinghani, A., & Weisz, J. R. (2023). Project SOLVE: Randomized, school-based trial of a single-session digital problem-solving intervention for adolescent internalizing symptoms during the coronavirus era. School Mental Health, 15(3), 955–966. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-023-09598-7

- Fox, J., & Weisberg, S. (2019). An R Companion to applied regression (3rd ed.). Sage, Thousand Oaks CA. https://socialsciences.mcmaster.ca/jfox/Books/Companion/

- Garber, J., Frankel, S. A., & Herrington, C. G. (2016). Developmental demands of cognitive behavioral therapy for depression in children and adolescents: Cognitive, social, and emotional processes. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 12, 181–216. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032814-112836

- Gonsalves, P. P., Nair, R., Roy, M., Pal, S., & Michelson, D. (2023). A systematic review and lived experience synthesis of self-disclosure as an active ingredient in interventions for adolescents and young adults with anxiety and depression. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 50(3), 488–505. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-023-01253-2

- Gross, J. J. (2015). Emotion regulation: Current status and future prospects. Psychological Inquiry, 26(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2014.940781

- Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 85(2), 348–362. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348

- Gullone, E., & Taffe, J. (2012). The Emotion Regulation Questionnaire for Children and Adolescents (ERQ–CA): A psychometric evaluation. Psychological Assessment, 24(2), 409–417. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025777

- Hedeker, D., & Gibbons, R. D. (2006). Longitudinal data analysis. Wiley-Interscience.

- Hollinsaid, N. L., Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Fox, K. R., & Schleider, J. L. (In preparation). Does multilevel stigma moderate single-session intervention efficacy for sexual and gender minority adolescents?. https://osf.io/35gn2

- Hollinsaid, N. L., Pachankis, J. E., Mair, P., & Hatzenbuehler, M. L. (2023). Incorporating macro-social contexts into emotion research: Longitudinal associations between structural stigma and emotion processes among gay and bisexual men. Emotion, 23(6), 1796–1801. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0001198

- Hollis, C. (2022). Youth mental health: Risks and opportunities in the digital world. World Psychiatry, 21(1), 81–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20929

- Hughes, J. L., Camden, A. A., & Yangchen, T. (2016). Rethinking and updating demographic questions: Guidance to improve descriptions of research samples. Psi Chi Journal of Psychological Research, 21(3), 138–151. https://doi.org/10.24839/2164-8204.JN21.3.138

- John, O. P., & Gross, J. J. (2004). Healthy and unhealthy emotion regulation: Personality processes, individual differences, and life span development. Journal of Personality, 72(6), 1301–1333. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00298.x

- Kaiser Family Foundation. (2023). Mental health care Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs). KFF. Retrieved December 15, 2023, from https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/mental-health-care-health-professional-shortage-areas-hpsas/

- Kataoka, S. H., Zhang, L., & Wells, K. B. (2002). Unmet need for mental health care among U.S. children: Variation by ethnicity and insurance status. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(9), 1548–1555. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1548

- Kazdin, A. E. (2019). Annual research review: Expanding mental health services through novel models of intervention delivery. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60(4), 455–472. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12937

- Kazdin, A. E., & Blase, S. L. (2011). Rebooting psychotherapy research and practice to reduce the burden of mental illness. Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 6(1), 21–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691610393527

- Kessler, R. C., Demler, O., Frank, R. G., Olfson, M., Pincus, H. A., Walters, E. E., Wang, P., Wells, K. B., & Zaslavsky, A. M. (2005). Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders, 1990 to 2003. New England Journal of Medicine, 352(24), 2515–2523. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa043266

- Key, K. D., Furr-Holden, D., Lewis, E. Y., Cunningham, R., Zimmerman, M. A., Johnson-Lawrence, V., & Selig, S. (2019). The continuum of community engagement in research: A roadmap for understanding and assessing progress. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, & Action, 13(4), 427–434. https://doi.org/10.1353/cpr.2019.0064

- Kingery, J. N., Roblek, T. L., Suveg, C., Grover, R. L., & Al, E. (2006). They’re not just “little adults”: Developmental considerations for implementing cognitive-behavioral therapy with anxious youth. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 20(3), 263–273. https://doi.org/10.1891/jcop.20.3.263

- Kitson, A., Antle, A. N., & Slovak, P. (2023). Co-designing a virtual reality intervention for supporting cognitive reappraisal skills development with youth. In Proceedings of the 22nd Annual ACM Interaction Design and Children Conference, Chicago, Illinois (pp. 14–26). https://doi.org/10.1145/3585088.3589381

- Klasnja, P., Hekler, E. B., Shiffman, S., Boruvka, A., Almirall, D., Tewari, A., & Murphy, S. A. (2015). Microrandomized trials: An experimental design for developing just-in-time adaptive interventions. Health Psychology, 34(Suppl), 1220–1228. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000305

- Kowarik, A., & Templ, M. (2016). Imputation with the R package VIM. Journal of Statistical Software, 74(7), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v074.i07

- Larsson, A., Hooper, N., Osborne, L. A., Bennett, P., & McHugh, L. (2016). Using brief cognitive restructuring and cognitive defusion techniques to cope with negative thoughts. Behavior Modification, 40(3), 452–482. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445515621488

- Lebrun-Harris, L. A., Ghandour, R. M., Kogan, M. D., & Warren, M. D. (2022). Five-year trends in US Children’s health and well-being, 2016–2020. JAMA Pediatrics, 176(7), e220056. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.0056

- Leijten, P., Weisz, J. R., & Gardner, F. (2021). Research strategies to discern active psychological therapy components: A scoping review. Clinical Psychological Science, 9(3), 307–322. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702620978615

- McDanal, R., Shen, J., Fox, K. R., Eaton, N. R., & Schleider, J. L. (2024). Predicting Transdiagnostic symptom change across diverse demographic groups in single-session interventions for adolescent depression. Clinical Psychological Science, https://doi.org/10.1177/21677026231199437

- McDonald, R. P. (1999). Test theory: A unified treatment. Psychology Press. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9781410601087/test-theory-roderick-mcdonald

- McRae, K., Ciesielski, B., & Gross, J. J. (2012). Unpacking cognitive reappraisal: Goals, tactics, and outcomes. Emotion (Washington, D.C.), 12(2), 250–255. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026351

- Morello, K., Schäfer, S. K., Kunzler, A. M., Priesterroth, L.-S., Tüscher, O., & Kubiak, T. (2023). Cognitive reappraisal in mHealth interventions to foster mental health in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Digital Health, 5. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fdgth.2023.1253390

- Ng, M. Y., DiVasto, K. A., Cootner, S., Gonzalez, N., & Weisz, J. R. (2023). What do 30 years of randomized trials tell us about how psychotherapy improves youth depression? A systematic review of candidate mediators. Clinical Psychology Science & Practice, 30(4), 396–419. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12367

- Ng, M. Y., DiVasto, K. A., Gonzalez, N., Cootner, S., Lipsey, M. W., & Weisz, J. R. (2023). How do cognitive behavioral therapy and interpersonal psychotherapy improve youth depression? Applying meta-analytic structural equation modeling to three decades of randomized trials. Psychological Bulletin, 149(9–10), 507–548. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000395

- Ng, M. Y., Eckshtain, D., & Weisz, J. R. (2016). Assessing fit between evidence-based psychotherapies for youth depression and real-life coping in early adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology: The Official Journal for the Society of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, American Psychological Association, Division, 45(6), 732–748. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2015.1041591

- Olfson, M., Gameroff, M. J., Marcus, S. C., & Waslick, B. D. (2003). Outpatient treatment of child and adolescent depression in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60(12), 1236–1242. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.60.12.1236

- Osborn, T. L., Rodriguez, M., Wasil, A. R., Venturo-Conerly, K. E., Gan, J., Alemu, R. G., Roe, E., Arango, G. S., Otieno, B. H., Wasanga, C. M., Shingleton, R., & Weisz, J. R. (2020). Single-session digital intervention for adolescent depression, anxiety, and well-being: Outcomes of a randomized controlled trial with Kenyan adolescents. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 88(7), 657–668. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000505

- Pennant, M. E., Loucas, C. E., Whittington, C., Creswell, C., Fonagy, P., Fuggle, P., Kelvin, R., Naqvi, S., Stockton, S., & Kendall, T. (2015). Computerised therapies for anxiety and depression in children and young people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 67, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2015.01.009

- Racine, N., McArthur, B. A., Cooke, J. E., Eirich, R., Zhu, J., & Madigan, S. (2021). Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: A meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 175(11), 1142–1150. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2482