Abstract

The manner in which public diplomacy is being practiced is constantly evolving, new means are being developed to create political relationships between states and international publics. Countries are competing globally for the hearts and minds of international publics in their quest for gaining and accumulating soft power. This quest is driven by the assumption that soft power gives countries that possess it advantages, such as a freer hand in foreign policy or attracting foreign investment. Russia is one of those countries that is competing in the global arena, and have been developing their tools of new public diplomacy. One of these tools is the creation and the use of NGOs, which are directed at creating an information environment where Russian policy better placed to be realized.

INTRODUCTION

Both in theory and practice public diplomacy has undergone change from the years of the Cold War. Heine characterized diplomacy as moving from a “club” to a “network” model (Citation2006: 3–10). Diplomacy used to be the preserve of governments. In its current form it includes a multitude of different actors, each vying for attention and influence. It is moving toward a much more engaged and active form of communication and interaction. More and more countries are beginning to compete in an increasingly crowded international marketplace of actors seeking to communicate with and influence international publics. There are a variety of reasons for wanting to communicate and engage audiences, which range from tourism, attracting foreign investment, national image and influencing international affairs.

When the Soviet Union collapsed in the end of 1991, the newly independent Russian Federation considerably reduced its presence (from that of the Soviet Union) on and in the globe. Now it is engaged in the process of reappearing in the public diplomacy arena. But why has this taken place now? One of the primary motivations for Russia to communicate to the world’s publics, which has surfaced in debates among experts, politicians and diplomats is that the country is not appreciated enough internationally.Footnote1 Changes in the political and communication landscape have allowed new actors (nonstate) to enter the international relations and affairs arena, which includes corporations and nongovernmental organizations (Melissen Citation2011; Seib Citation2012). These organizations can be independent of the state, and consequently can work against or in concert with official (governmental) policy.

As stated above, public diplomacy is in the process of transforming. This process (of active public outreach in diplomacy) has been largely led by the United States to date, and there are many different studies that record this fact (Seib Citation2009; Snow and Taylor Citation2009). What about the efforts and progress of other states? This is gaining some more academic interest recently, and this paper intends to try and make a modest contribution to this literature. The question that it seeks to address, in light of the changing nature of public diplomacy, is how does the Russian state direct and implement its New Public Diplomacy program with the use of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs)? Issues pertaining to the nature of these organizations and how they operate (especially with regard to relationship building and attempted influence) shall also be explained.

There are two different frameworks used to try and make theoretical sense of the different empirical material in this work. Political marketing is used to try and make sense of the nature of the relationships that are formed between the political communicator and the different publics and stakeholders. Public Diplomacy, and more specifically New Public Diplomacy shall be used to try and make sense of the dimension of Government-to-Public (G2P) communication in the international sphere. A synthesis of the two is hoped to provide a good all-round perspective of the use of NGOs in international relations and affairs. There also needs to be a theoretical/conceptual motivation for engaging in this sort of communication and interaction globally. This is supplied through Joseph Nye’s concept of soft power. His understanding and definition of the concept shall be given, before moving to how the concept is understood and practiced by Russia (more specifically those official circles engaged in understanding and wielding soft power).

A select number of different NGOs shall be detailed and analyzed. This represents a small number of the total that are in existence, but sufficient to make sense of the primary trends and to answer the posed research question.

THEORETICAL UNDERPINNINGS

Political Marketing

Political product is conceptualized as being an amalgam of party image, leader image and manifesto (Johansen Citation2012: 106). The aspect of political production involves the issue of supply (politicians) and demand (voters). Political consumption is not solely related to the outcome, but potentially also includes a participatory process. In this regard, the notion of participatory opportunity is important (Newman Citation1999; Cwalina, Falkowski, and Newman Citation2011; Johansen Citation2012: 42; Ormond, Henneberg, and O’Shaughnessy Citation2013). Political markets are understood as being the places where producers meet consumers (Johansen Citation2012: 161). Marketing in the political sphere has several similarities with the services industry. Namely, that they are:

Intangible;

Heterogeneous;

Inseparability—production, distribution, and consumption are simultaneous processes;

An activity or process;

Core-value produced in buyer-seller interactions;

Customers participate in production;

Cannot be kept in stock;

No transfer of ownership (Johansen Citation2012: 29).

The above implies a blurring of boundaries between process and production, “seller” and “buyer”, a complex environment is at play where simultaneous processes and actions occur. Johansen goes on and points out that “[…] in sophisticated services industries, the quality of the process will effectively influence the quality of the end product” (2011: 47).

This has created theoretical development to try and understand political production. Political marketing is a relatively new subdiscipline that has emerged from marketing, and includes a political science perspective (Johansen Citation2012; Ormond, Henneberg, and O’Shaughnessy Citation2013). The concept is something that is in vogue in an age where there is an increasing trend of political alienation and disengagement among the people. But what exactly is political marketing, and what does it entail? There are several different ways of seeing and understanding the concept. Two different interpretations shall be given here,

Political marketing is a perspective from which to understand phenomena in the political sphere, and an approach that seeks to facilitate political exchanges of value through interactions in the electoral, parliamentary and governmental markets to manage relationships with stakeholders (Ormond, Henneberg, and O’Shaughnessy Citation2013: 18).

Within this definition, political marketing concerns exchanges of value, relationships and stakeholders. There also needs to be a further clarification, the exact nature of the exchange needs to be defined. An older view and definition of political marketing provides a more managerial understanding of the concept,

[…] it claims that marketing is a specific form of economic rationality that offers insights in to the strategic options and behaviors of parties. It shares with history a desire to investigate and explain the behavior of leading political actors, and thus its focus extends from campaigning into the high politics of government and party management (Johansen Citation2012: 6).Footnote2

Another view of political marketing is offered by Lilleker (Citation2011: 151), which includes some previously neglected issues by the previous two definitions,

Political marketing refers to the use of marketing tools, concepts and philosophies within the field of policy development, campaigning and internal relations by political parties and organizations. It is seen as a reaction to the rise of political consumerism, and the collapse of partisanship, in Western democratic societies as well as emergent democracies.

The earlier definition does not include aspects such as exchanges of value or relationship building. Instead it focuses upon a more managerial approach, with a top-down perspective. The third definition now includes the issue of policy development, but this is restricted up to the level of a national setting. Political actors and their behavior form the central theme. This particular paper favors the first version given (the most recent definition of the relational approach). Leaving the target public out of the analytical map severely restricts the ability to understand the process that leads to the eventual outcome. There are two different interpretations of political marketing—wide and narrow. The wide interpretation not only includes the marketing activities, but also the political environment (Ormond, Henneberg, and O’Shaughnessy Citation2013: 26). A narrow view provides a description and application of political marketing strategies and instruments (Ormond, Henneberg, and O’Shaughnessy Citation2013: 32). This paper tends to adhere to the wide perspective of political marketing.

Several developments have been taking place within the political marketing sphere, which influence its direction and application. In particular there has been an:

Increasing sophistication of communication and spin;

Emphasis on product and image management, including candidate positioning and policy development;

Increased sophistication of news management, that is, the use of free media;

More coherent and planned political marketing strategy development;

Intensive and integrated use of political market research;

Emphasis on political marketing organization and professionalization of political management (Ormond, Henneberg, and O’Shaughnessy Citation2013: 23).

These changes and developments seem to signal a direction that focuses upon political image and reputation through carefully managing the channels of information and communication. That is, to show a carefully cultured façade to the target publics. It also reveals that production, sales and marketing are all intertwined. The marketing of a political product itself does not exist in a vacuum. As noted by Johansen, “the marketing of a product is affected not only by the strength of its brand in comparison with its competitors, but also by the overall standing of the whole class of products and their sector” (2011: 47). Other competitors in the market may influence the political offering. One of the avenues to position a political product is not to seek an “ideal” concept, but to offset the product concept that is offered by other actors (Johansen Citation2012: 106).

This being said, an actor does need to locate (position) themselves within the political market. Newman defines the role of positioning as “the connection a company (or organization) makes between its products and specific segments in the marketplace” (Citation1999: 45). One of four broad market positions can be held, as a leader, challenger, follower or nicher. The position then dictates the approach to exploiting the market (Johansen Citation2012: 113). These following aspects need to be determined by the communicating actor. A strategic posture, which is how an organization wants to be perceived relative to its competitors in the market (Ormond, Henneberg, and O’Shaughnessy Citation2013: 134) needs to be defined. Competitive position, which is how an actor intends to compete, is another element. The third part to be considered is the strategic orientation, decisions and trade-offs with regard to approaching markets and customer orientation issues (Ormond, Henneberg, and O’Shaughnessy Citation2013: 134). These aspects combined, in part, give direction for a political actor. This is only part of the whole picture.

An increasing trend in political marketing is a new focus on “building value-laden relationships and marketing networks in the form of social contracts with citizens.” It is gradually moving away from transactional exchanges (Ormond, Henneberg, and O’Shaughnessy Citation2013: 116).Footnote3 In addition, it has been found that organizations that promote high ethical values perform better than those that do not (in terms of meeting organizational goals and objectives) (Johansen Citation2012: 85). In addition to ethics and values, ideology plays an important role in political reputation, which serves as a form of brand identity and a potential link with target publics (Newman Citation1999: 45). It is important to bear in mind that cooperative relationships are not always about exchange, but engaging in joint value creation (Johansen Citation2012: 92). This implies a specific approach within political marketing, which requires a system of active communication and relationship building. Expressed and communicated ethics, values and ideology help to create a brand identity to differentiate an actor in the political marketplace and to help positioning them as a unique and desirable “product.”

Relational marketing is the specific angle that takes the above points in to consideration and moves away from a purely managerial view of the communication process. It implies several specific characteristics.

“Product” is understood as both a process and an outcome;

Market communication is seen as a two-way process;

Approach becomes more strategic than tactical in nature (Johansen Citation2012: 73).

The process requires the active political participation of the target audience in order for a functional relationship to form. This means that trust and commitment are key parts of relational marketing (Johansen Citation2012: 49). And ultimately, loyalty is the result of the existence of shared values and inclusion (Johansen Citation2012: 181). Within the bounds of the relationship that is formed, a leader and the followers can emerge. A leader is based upon the notion of a strong conviction. There is also the element of a long-term commitment to understanding the audience and the ability to empathize with their key constituents (Ormond, Henneberg, and O’Shaughnessy Citation2013: 135).

In this article, political process needs to be viewed as an opportunity to influence the development of international politics/relations through symbolic association/membership with like-minded individuals and groups by forming relationships and contributing to the conversation through voicing opinion and policy positions. Therefore, the “market” is seen as being international public opinion, and the interaction between the government and “activist” or researcher segments of this market.

Within the context of this article, political marketing should be viewed as an attempt to manage/influence the political environment of international relations and affairs by a political body (which can include a country, International Governmental Organization and so forth). This is done through the forming and managing of relationships with different stakeholders located domestically and abroad. The relationship is based upon an exchange of views and values through direct and indirect means, where attraction forms the conduit for the connection. In the international relations context, transforming the application from a local/national level to an international one, votes for a candidate can be seen in the light of public opinion (toward a country’s image and reputation). Campaigning for elections is transformed in lobbying for policy objectives. The process of campaigning is a continuous one, which may be more intensive at times owing to a specific objective.

New Public Diplomacy

There is a need to utilize a means for projecting a country’s attractiveness internationally. Public diplomacy is something that has been in existence for a long time in practice (Jowett and O’Donnell Citation2012: 287), but is still very much in vogue. The term, at times, is used inter-changeably with propaganda or nation branding, which tends to add confusion as to its purpose (Szondi Citation2008). It is a term that is often uttered, but what does it mean and entail? One possible explanation for its purpose is given below,

Public diplomacy […] deals with the influence of public attitudes on the formation and execution of foreign policies. It encompasses dimensions of international relations beyond traditional diplomacy; the cultivation by governments of public opinion in other countries; the interaction of private groups and interests in one country with another; the reporting of foreign affairs and its impact on policy; communication between those whose job is communication, as diplomats and foreign correspondents; and the process of intercultural communications (Jowett and O’Donnell Citation2012: 287).

The above-mentioned quote dovetails with the hierarchy of impacts that public diplomacy can potentially achieve—increasing peoples’ familiarity with one’s country, increasing peoples’ appreciation of one’s country, getting people engaged with one’s country and influencing people (Leonard et al Citation2002: 9–10). L’Etang says that this can involve offering a nation’s cultural capital to target countries to generate goodwill with younger generations (Citation2011: 241). Others, such as Seib, note that “public diplomacy is a process, but it cannot be separated from policy” (Citation2012: 122). This has implications for the underlying reasons for engaging in PD, other than the superficial aspect of making a country more “likeable.” Common objectives for PD include: increasing awareness, managing reputations, changing legislation or altering attitudes (Coombs and Holladay Citation2010: 299).

There are five elements of public diplomacy, which are identified by Nicholas Cull. Listening: collecting the opinions and data from the target audience through listening, rather than speaking to them; advocacy: an active function where the messenger attempts to promote a certain idea or policy that benefits them; cultural diplomacy: making known and promoting a country’s cultural resources and accomplishments. In effect, an exporting of culture; exchange diplomacy: to send abroad and to receive people for a period of study and/or acculturation, thereby exporting ideas and ways of doing things; international broadcasting (news): an attempt to manage the international environment through mass media assets, to engage the foreign publics (Jowett and O’Donnell Citation2012: 287–88). These require an understanding of the various elements to create an effective approach.

Seib (Citation2012: 112) notes that “public diplomacy is related to media accessibility and influence.” The message must be seen and heard in the public information space. However, other considerations also need to be taken into account. There are three elements to public diplomacy—news management, strategic communication and relationship building (Leonard et al Citation2002). This paper’s primary focus is on the element of relationship building, but does include some aspects of the other two as well.

Public diplomacy as a tool of international relations has not stood still and ceased to develop, to meet new needs and challenges in a rapidly changing global environment. Nancy Snow distinguishes between what she terms as being Traditional Public Diplomacy and New Public Diplomacy. The listed features of Traditional Public Diplomacy include: Government to Publics (G2P); official in nature; “necessary evil” as technology and new media democratized international relations; linked to foreign policy/national security outcomes; one-way informational and two-way asymmetric (unequal partners in communication); give us your best and brightest future players; passive public role; and crisis driven and reactive (Snow Citation2010: 89).

The New Public Diplomacy formula has several significant changes over the old noninteractive and reactive model. Its features include: Public to Public communication (P2P); unofficial actors present (NGOs, practitioners and private citizens); “everyone’s doing it”; active and participatory public; dialogue and exchange oriented, two-way symmetric; in general more reference to behavioral change; based upon relationship, systems and network theories (Snow Citation2010: 91–92). The political and information environment in the new model is much more dynamic, and involves a greater range of actors. Developments in information technology and politics has not only enabled, but pushed these changes as the information and political environment has evolved. This enables foreign governments to engage foreign audiences with political marketing within their public diplomacy programs.

The old and new variants of PD can simultaneously exist in the environment (Melissen Citation2011). However, one constraint that affects all forms of PD (and communication in general) is that words and deeds must match. In addition, the so-called Golden Rule of Public Diplomacy (Cull Citation2009: 27) is that there is no substitute for bad policy, it cannot be explained and glossed over. Previous experience in public diplomacy, in particular the US experience, have highlighted the importance for the need of a coordinated and fully integrated effort (Lord Citation1998: 68). Gregory Payne explains the necessary course to be taken in order for PD to stand a chance of succeeding:

[…] effective public diplomacy is rooted in strategic people to people communication in the effort to establish a sustaining relationship. And, fundamental to achieving success in such vital communication, regardless of the sponsorship of such activities, is a commitment to build a relationship with the targeted public through grassroots encounters (Payne Citation2009: 579).

There are some similarities here between PD and the relational marketing perspective of political marketing. One point in particular, which comes to the fore, is the notion of the added and joint value creation of the process. The creation of a functional and lasting relationship with a target public is in some regards, of more value than the immediate goal that initiated process.

SOFT POWER AND THE MOTIVATION FOR COMMUNICATION

The nature of power is also in the process of changing. According to Nye, power is capable of two things. An ability to get the desired outcomes, and to influence the behavior of others to achieve the desired outcomes (Citation2004:1–2). There are two alternative ways of wielding power—through fear and coercion or through attraction and co-opting. One needs to bear in mind that “power always depends on the context in which the relationship exists.” If objectives seem to be legitimate and just, others may willingly assist without the use of coercion or inducements (Nye Citation2004: 2). To proceed, there needs to be an understanding of power.

Power’s definition is related to vested interests and values. Some argue that it is related to the ability to make or resist change (Nye Citation2011: 5). A dictionary definition states that power is “the capacity to do things and in social situations to affect others to get the outcomes we want” (Nye Citation2011: 6). Nye contends that power is a two-way relationship, which is defined by who is involved in the power relationship (scope of power) and what topics are involved (domain of power) (Citation2011: 6–7). In the context of this paper, power and influence are to be viewed as being related and interchangeable.

Hard power’s basis is found in military and economic weight. This is in contrast to soft power that “rests on the ability to shape the preferences of others” (Nye Citation2004: 5). Soft power is about establishing the preferences, normally associated with intangible assets—attractive personality, culture, political values and institutions, and policies seen as being legitimate or having moral authority. If a leader represents values that others want to follow, it will cost less to lead (Nye Citation2004: 6). In terms of a country, soft power can be found in its culture, its political values and foreign policy (Nye Citation2004: 11). This is the aspect that makes the theoretical lenses of political marketing and public diplomacy an effective tool for understanding the dimensions of politics and diplomacy.

Military or hard power assets are more government controlled/owned than soft power assets (Nye Citation2004: 14). In this regard, there is a resemblance to the nature and practice of New Public Diplomacy. (Nye Citation2004: 16) also notes that “soft power is also likely to be more important when power is dispersed in another country than concentrated” (dictator for example). Soft power is particularly relevant to the realization of milieu goals (Nye Citation2004: 17). A “drawback” of soft power is the resources work more slowly, they are more diffuse in nature, and more cumbersome to wield than hard power resources” (Nye Citation2004: 100). This means that they are harder to use, easy to lose, and the results take a longer time to become apparent.

The system of “soft power resources work indirectly by shaping the environment for policy, and sometimes take years to produce the desired outcomes” (Nye Citation2004: 99). This leads to a point of criticism concerning soft power, which is that it has only a modest impact on policy outcomes (Nye Citation2004: 15). The basis of soft power is dependent upon the credibility of the communicator, which is where the use of political marketing and New Public Diplomacy come in to their own. These communicational technologies are designed to build the necessary relationships that contribute to credibility. The policy-oriented concept of power tells—who gets what, how, where and when (Nye Citation2011: 7). How is power that is gained from accumulating soft power established and wielded in practice?

A first point to consider is that “information creates power, and today a much larger part of the world’s population has access to that power” (Nye Citation2011: 103). Political marketing and New Public Diplomacy are about creating the relationships and establishing the environmental (political and information flows) conditions between a state and foreign publics, NGOs (which shall be discussed further on) are one of the means to influence the relational power between these groups. Three aspects to relational power exist—commanding change, controlling agenda and establishing preferences (Nye Citation2011: 11). I would argue that with the current state of information technologies it is difficult to control an agenda completely, however, it is possible to initiate or influence.

As has been stated several times, soft power is contingent upon the image, reputation and credibility of a country. This is a necessary base for being able to attract and influence others. There are three clusters of qualities of agent and action that are central to the notion of attraction - benignity, competence and beauty (charisma) according to Alexander Vuving.

Benignity—how an agent relates to others and hence how they are perceived;

Brilliance/Competence—how an agent acts, produces an effect;

Beauty/Charisma—agent’s relation to ideals, values and vision can produce admiration of adherence (Nye Citation2011: 92).

These qualities not only concern the issue of communication, but also interaction with the target public. Reputation and credibility, which lead to attractiveness are not only based upon the word only, actions must also align with words to generate the final image. This not only concerns how one should project themselves, but also about how this projection is received among the target public.

Soft power is openly sought by many countries in the global competition for it. Some paradoxes emerge, such as the presence of PD and an absence of soft power and vice versa. For instance, Cull (Citation2009: 15) points out that North Korea has PD, but an absence of soft power. Whereas Ireland has soft power, but minimal PD. Too much focus on the quest for soft power may ultimately prove counter-productive for an actor (it can be viewed with suspicion by publics). The Russian 24-h news channel, RT (formerly Russia Today), is available on many different cable networks and is a good example of an attempt to engage in the pursuit of soft power through attempting to engineer a rebranding.

There has been a great deal of discussion in Russia concerning soft power and public diplomacy, how these concepts currently relate and how to develop the potential further. A constraint in this regard is Russia's current brand, and how to rebrand the national image (Simons Citation2011). One of the debates has been to look at the United States and see if there is anything that can be learned and applied for Russia. This not only includes the theoretical and conceptual levels, but the creation of institutions as well (such as the idea to create a Russian equivalent of the US Information Agency).Footnote4 There are others that advocate that Russia should develop its own soft power concept (application techniques, development strategies, priorities and objectives).Footnote5 Both of these sides see an urgent need to develop a viable soft power concept, otherwise Russia’s international position and potential will be eroded.

A seeming consensus does exist on the need for Russia to engage in soft power, through effective global communications. This includes communicating what is termed as objective information about Russia. The perceived reward is that Russia shall be more successful in attaining its stated foreign policy objectives and to protect Russian interests, however, the first step being to possess a resource of soft power.Footnote6

In July 2012, President Putin defined soft power as being “all about promoting one’s interests and policies through persuasion and creating a positive perception of one’s country, based not just on its material achievements but also its spiritual and intellectual heritage.”Footnote7 This is in-line with an earlier observation made by Georgy Filimonov from People’s Friendship University (Moscow). He made strong connections between the accumulation of soft power and an effective and a functional system of public diplomacy,

I believe it is quite legitimate to treat the concept of public diplomacy as a system of strategic views aimed at forming a positive image of a country abroad through the implementation of multi-level information and advocacy policy. The main directions of this policy are foreign cultural policy, cultural diplomacy, information and ideological promotion, educational exchange programs, the involvement of a wide range of nongovernmental organizations and other civic institutions, the corporate sector … etc. Moreover, in contrast to traditional diplomacy, public diplomacy is addressed directly to the public. Therein lies its strength and effectiveness.Footnote8

Efforts to develop Russia’s public diplomacy and ability to accumulate soft power potential, as described above, rely on the use of mass communication with foreign audiences to explain official policy. This comes against a backdrop where Russia considers itself at a disadvantage on the international stage owing to a poor image and reputation that has been the result of “lack of understanding” and “bad” (nonobjective) information in the global information space. There have been an increasing number of institutions created, which communicate and form relationships with an increasing number of people in foreign publics. Yet, the image of Russia has not improved. This has led to some stating that Russia is losing its soft power quest. An underlying reason given, is that this does not concern Russia’s cultural or intellectual heritage and reputation, but more precisely a lack of popularity in its pursued policies.Footnote9 The above hints that the quest for soft power can be initiated by a country that finds itself in a defensive position, which then seeks to extricate itself from this predicament through self-redefinition.

Although power is something that is greatly sought by many countries around the globe, it is something that is hard to observe and accurately measure. Power is something that is extremely difficult to measure and quantify (Nye Citation2011: 3). It is an intangible asset, so it cannot be directly seen or touched, but it can exert an effect. It is much easier to measure activity than effect, which makes the temptation greater to try and show progress through showing what concrete activities have been performed rather than trying to measure what preferences or opinions have been influenced. In this light, opinion polls are an imperfect, yet essential measure of soft power resources. At least it provides a good first approximation (Nye Citation2004: 18). The BBC’s annual Country Ratings Poll is an example of one such poll that can provide a yardstick.

NGOS FUNCTION WITHIN NEW PUBLIC DIPLOMACY

Nonstate actors are increasingly player a greater role in public diplomacy around the world, these include such entities as corporations and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). One view is that although these organizations are not an official part of the governmental efforts, they can effectively contribute toward achieving foreign policy goals (such as the promotion of democracy and human rights) (Nye Citation2004; Snow Citation2006; Zhang and Swartz Citation2009; Payne Citation2009).

The term NGO is a contentious one and there are many different definitions for a broad category of different organizations. Yet, it is still critical to give a concrete definition for this term. A United Nations document from 1994 defines NGOs as a “non-profit entity whose members are citizens or associations of citizens of one or more countries and whose activities are determined by the collective will of its members in response to the needs of the members of one or more communities with which the NGO cooperates.”Footnote10

Zhang and Swartz (Citation2009: 49) identify four reasons for the increased role and effectiveness of NGOs in public diplomacy:

NGOs no longer trust governments to represent their concerns on international matters;

The increased sense of entitlement and expectation to engage in the policy making process as a result of an increased sense in the notion of democracy (participative);

The technological revolution enables instant access to marketing agendas globally;

International leadership is determined by the power of ideas, and especially the way these ideas are communicated.

The above observation suggests that changes taking place in the environments of politics and technology has enabled and enticed new players to enter the stage of public diplomacy. Bruce Wharton, the Director of Public Diplomacy for the State Department’s Bureau of African Affairs went further, and noted that “NGOs provide an incredible voice and reach beyond traditional audiences by recognizing that not one size fits all. All public diplomacy is local. People on the ground know best.”Footnote11 Leonard, Stead and Smewing observe that NGOs competitive advantage over governments is that they possess credibility, expertise and appropriate networks (2002: 56).

One of the most efficient ways of establishing trust and credibility is through the use of face-to-face contact (Johansen Citation2012: 183; Seib Citation2012; Nye Citation2004: 111). Snow and Taylor (Citation2009: 10) note that forming relationships with publics is far more effective than managing reputation or image. It gives publics first-hand experience through direct interaction. Reputation and image are often experienced second-hand and are less specific concepts. In this regard, NGOs are an ideal mechanism with which to engage and interact with publics to form relationships, and engender trust and credibility.

These reasons provide several good arguments for the role of NGOs in international affairs. Other reasons also exist, which add more reasons for states in allowing NGOs to cooperate and work together on issues. There is an increasing trend where people are increasingly suspicious of authority and governments (Nye Citation2004: 113). NGOs can be seen as being more neutral and objective, and consequently as being a more legitimate actor (Payne Citation2009: 604; Riordan in Melissen, Citation2005: 191).Footnote12 This is an important aspect, when considering that a functional relationship requires a sense of trust and legitimacy between the communicator and the publics.

The task of creating political meanings and reality out of a myriad of messages from a political campaign is a complex task. Symbols and information given by political actors are intended to form and influence attitudes and preferences. “Political meaning is conveyed through the media and their interpretations and perceptions.” Therefore, there is an attempt to shape media content as media create the constructed reality of the target publics (Newman Citation1999: 106). If a political actor perceives that they are at a disadvantage through entrenched negative stereotypes, biases and framing, it provides an impetus to locate and exploit other means of communication to circumvent and challenge the situation. NGOs are one such opportunity through their ability for direct contact with target publics and an ability to communicate to those publics without going through the lens of the media first.

RUSSIAN NGOS AND THEIR FUNCTION

Within the framework and for the purposes of this article, when I speak of NGOs, this is in a wide interpretation of organizations that includes NGOs, GONGOs, nonprofit organizations, and think tanks. There may be some that disagree with this lumping together of diverse kinds of organizations, my primary motivation is that there is an attempt to influence perception that these organizations are more neutral in their character. Even if they are in fact working directly or indirectly for government directed goals and objectives, and therefore their independence is put into question.

The Color Revolutions illustrated Russia’s failure in terms of its projected soft power and diplomacy, with an apparent inability to influence events. It spurned an effort to evaluate and draw lessons from the experience, and to understand the role of American sponsored or led NGOs (Orlova in Seib Citation2009: 77). Reflection and analysis of the Color Revolutions by Russia seemed to provoke a couple of reactions, to become suspicious of the activity of NGOs that engage in politically sensitive issues on its territory and an attempt to curtail their activity (e.g., the NGO funding law). The second point, seems to be the effort to develop their own capacity and use of NGOs in pursuit of Russian foreign policy goals.

The Russian Foreign Ministry maintains and cultivates relations with NGOs, where these organizations interact on various international topics. This also functions at the formal level, on 7 May 2012, President Putin signed into law On Measures to Implement the Foreign Policy Course of the Russian Federation,Footnote13 which specifically mentions a role for civil society (including NGOs) in the foreign policy process. In 2012 some 250 events within the framework of Foreign Ministry and NGO interaction were held. Relations with the Public Chamber are developing, and RossotrudnichestvoFootnote14 maintains relations with some 150 NGOs. Various topics and causes are focused upon, such as supporting compatriots abroad, social policy, culture, human rights and inter-civilizational dialogue. Many of the NGOs focus on US and European publics. New geographical focus areas for NGOs activities and work are emerging in China, India, Africa, Latin America and countries of South East Asia.Footnote15 There are currently some 5000 officially registered NGOs involved in foreign policy, of which 859 possess an international status.Footnote16 The size and breadth of the use of NGOs in public diplomacy is considerable. A select number of those NGOs shall be detailed below.

Under the presidency of Dmitry Medvedev, some measures were taken to enhance Russian PD potential and efforts. On 2 February 2010, President Medvedev signed decrees that established the Alexander Gorchakov Fund to Support Public Diplomacy (http://gorchakovfund.ru/) and the Russian International Affairs Council (http://russiancouncil.ru/en/). Both organizations are located within the structure of the Foreign Ministry, and the Russian International Affairs Council is also associated with the Ministry of Education. The funding of these organizations comes from the state budget.Footnote17 Their role is explained by the NGO Equal Right to Life. “The Alexander Gorchakov Public Diplomacy Fund actively promotes the integration of Russian nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in the international sphere, supporting NGOs, which together with government show their foreign policy activity for the successful formation of decent social, political and business image of Russia in the world.”Footnote18 The President of the Russian International Affairs Council, Igor Ivanov noted that with regard to the active participation of society and public organizations in international affairs that “Russia is seriously lagging behind other countries and, consequently, it is at a disadvantage in the formation of public opinion abroad.”Footnote19

The Russian International Affairs Council gives a brief paragraph of information concerning its status as an organization and its goals,

Nonprofit partnership Russian International Affairs Council (NPP RIAC) is a nonprofit membership organization. RIAC activities are aimed at strengthening peace, friendship and solidarity between the peoples, preventing international conflicts and promoting crises settlement. The partnership was established upon the decision of the cofounders and in compliance with the instruction of the President of the Russian Federation #59-rp of February 2, 2010 “On creation of a nonprofit partnership Russian International Affairs Council.”Footnote20

This organization is in keeping with the notion of New Public Diplomacy that states actors other than established state institutions, such as the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, become involved in diplomacy. Having said this, both of the above-mentioned organizations are closely associated with the state. Their mission statement contains several different values and goals, including the fact that it seeks to fulfil foreign policy objectives. “RIAC mission is to facilitate the prospering of Russia through its integration in the global world. RIAC is a link between the state, expert community, business and civil society in an effort to find foreign policy solutions.”Footnote21 Thus diplomacy is moving away from a reactive stance to a much more proactive form, which includes the element of relationship building.

The Alexander Gorchakov Public Diplomacy Foundation, which has information on its website in Russian only, sets out its mission and purpose. It provides “an integrated support for domestic civil society institutions. Together we can achieve the synergy, actively working on a common goal: the creation of the world public the correct presentation of Russia and our national cultural values.”Footnote22 It appears as though the primary role for this organization is to perform an organizing and coordinating body for other NGOs working in the sphere of international relations. Part of the given mission statement includes “[…] the Foundation’s mission is to promote the development of public diplomacy, as well as to facilitate the creation of a favorable for Russia, social, political and business environment abroad.”Footnote23 The two above-mentioned organizations are intended to create an interactive dialogue with different foreign target groups, and to form a relationship with them to be able to influence opinions and perceptions concerning Russia. This suggests that New Public Diplomacy is becoming the preferred method, which is facilitated with the relationship marketing approach.

The Gorchakov Foundation does run several special programs, such as the Baltic Dialogue (for Russian speaking youth from the Baltic States) and the Caucasus Dialogue. With regard to the later program, the Caucasus Dialogue, it focuses upon the subject of historical accounts of the 19th Century Caucasian War (especially pertaining to the plight of the Circassian ethnic group). This is intended to act as informational support for the successful hosting of the Winter Olympic Games in Sochi in 2014.Footnote24 This is a very narrow purpose, but an important one as the hosting of these games can potentially accumulate soft power for the Russian Federation.

Another nonprofit organization, which was founded in 2008, is the Historical Memory Foundation. The director of the organization is a historian by the name of Alexander Dyukov. According to the organization’s website, its objectives are “to provide assistance for unbiased scientific researches of relevant issues of Russian and Eastern European history of the 20th century.” There is also a list of the different activities that Historical Memory Foundation engages in.

Topical subject research of Russian and Eastern European history of the 20th century;

Topical subject furtherance of researches of Russian and Eastern European history of the 20th century and their publications;

Conduct of science conferences and round tables;

Mass media presentation of research results of relevant issues of Russian and Eastern European history of the 20th century;

Cooperation with federal and local legislative and executive power authorities of the Russian Federation in accordance with the purpose and objectives of the Foundation;

Cooperation with Russian and foreign mass media and nonprofit organizations within the framework of the Foundation’s regulations activity;

Organization of scientific exchanges with foreign research centres and institutions in accordance with the purposes and objectives of the Foundation;

Publishing, informational, educational and lecture activities.Footnote25

These activities demonstrate that the organization seeks to try and influence the narrative on a relatively narrow set of issues and topics related to historical matters, through producing reading material and through organizing face-to-face interactions. The material on the website is available in two languages, Russian and English. Although, there is a lot of information missing in the English language version, such as the names of the Board of Trustees and those who work at the Foundation, which appear in the Russian language version. Another significant difference between the two versions was the presence of a Red Star symbol on the Russian language site, which was absent on the much more neutral (objective) looking visuals of the English language version. There is also information on the Russian language site that solicits for donations, and gives details where and how to donate money to the organization.

Various facts, figures and symbolism used on the two different language versions are not always compatible (in terms of ideals, values, and symbolism). The information from the website, which is given above, hints that the organization attempts to segment its targeted publics on at least two different levels—international and domestic. When reading through the two language versions of the Historical Memory Foundation, there was no seemingly solid link that ties it to the upper echelons of official Russia, which was detected in the two earlier mentioned organizations. The level of contacts with officials are at a much lower level (on the Board of Trustees there are some members within the State Archive Agency and Ministry of Foreign Affairs), which could suggest that this is acting in the capacity as an “independent” and patriotically oriented organization.

The Institute for Democracy and Cooperation (http://www.idc-europe.org/en) describes itself as a think tank, which was established in 2008 in response to international criticism.Footnote26 It has offices in New York and Paris. Their declared mission objectives and goals are:

To be part of the debate about the relationship between state sovereignty and human rights; about East–West relations and the place of Russia in Europe; about the role of nongovernmental organizations in political life; about the interpretation of human rights and the way they are applied to different countries; and about the way in which historical memory is used in contemporary politics.

The Institute broadly defends a conservative outlook on human rights and international relations. It believes that the nation-state is the best framework for the realization for human rights and that humanitarian intervention is often counter-productive. It is attached to the classical understanding of international law based on sovereignty and noninterference. At the same time, it believes that the political order should be underpinned by moral perspective, and specifically by the Judeo–Christian ethic which unites both the Eastern and Western parts of the European continent.

The Institute aims to promote debate on these issues by inviting speakers to give their opinion and to share their expertise. At its meetings, it always encourages all sides of the argument to be put.Footnote27

The position taken by the Institute is clearly stated, plus the goal of wishing to create dialogues and relationships on key international topics. Many of the key positions taken reflect those of the Russian government on major issues, such as humanitarian intervention and sovereign democracy. Natalia Narochnitskaya is the Director of the Institute, her background is carefully covered in a biography. This includes her time in the State Duma as a member of parliament, her ties to the Russian Orthodox Church, her academic credentials are supplemented with details about her career in the international sphere. The website has information available in English, French and Russian languages. There is an emphasis on face-to-face meetings/interaction and the creation of literature (that can be distributed hard copy or through the internet).

In June 2013, one of the latest organizations was registered in London, the Positive Russia Foundation. The creation of the nonprofit organization was sponsored by Baron Tim Lewin and David Burnside, the owner of New Century Media (http://newcenturymedia.co.uk/). The Director of the Foundation is Vasily Shestakov, State Duma Deputy and long-time associate of Vladimir Putin. This has been characterized as being a British initiative, with high-level approval (Prince Michael of Kent and Prime Minister David Cameron are named) to fulfil a need of providing information that is not seen through the “prism of anti-Russian propaganda.” The stated goal of Positive Russia is to shape and create a positive image of Russia in the United Kingdom. One of the functions is named as the clarification of Russian government policy to the British public.Footnote28 Although the geographical focus of this organization is very specific and narrow, its function within this area is in line with other NGOs working and cooperating in the sphere of Russian foreign policy and international relations, i.e., to explain government policy to a foreign public in an information sphere that projects a negative image of Russia. At the time of researching and writing this paper, there was no functional website for the Positive Russia Foundation.

All of the NGOs detailed here are geared towards creating relationships with different foreign (and in some instances domestic) publics. The reason for initiating these relationships is based upon the expectation that by doing so it may be possible to accumulate soft power capital, and if this is achieved then to realize different policy objectives. Many of the above NGOs are engaged in advocacy, information management and strategic communication. These activities are intended to facilitate political exchanges and interactions through publishing, public events and networking.

FUTURE RESEARCH AND JOINING THE DOTS THEORETICALLY

The idea of this paper was to test new theoretical boundaries within political marketing, using a nonstandard single case study (insofar as the case study involving Russia and moving beyond electoral politics). Several interesting possibilities have been discovered along the way, which shall be explained in later research.

One possible way of going about doing this is to test for those intangible and tangible elements that influence soft power through public diplomacy and political marketing. What are those values and actions that influence (opinions and actions) a foreign public the most? Is it the values or policy expressed? The right words at the right moment? Maybe, it is the brand and reputation of a country? An alignment of words and deeds? Perhaps, a combination of these? By answering such questions, the crossover effect in the integration of political marketing and public diplomacy and its influencing of the intangible aspects that contribute to the building of soft power should be revealed. This could be tested by questionnaires sent to countries that are targeted by promotional campaigns, which would hint at the various possibilities. The results of this could then be followed up by focus groups to discuss the identified connections in greater detail.

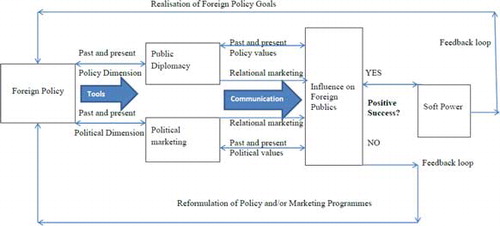

In the diagram below are the connections between public diplomacy, political marketing and soft power. At first mention, there seems to be little or no connection, but upon closer inspection there are several overlapping aspects. A first point to begin with is the intangible nature of foreign policy. There is no physical exchange taking place between the communicating country and the foreign audience. As in electoral politics, the offer of relationship is made, which is either accepted or ignored. This determines whether the policy is successful or not (in accumulating soft power and influence) as it relies on a process of coproduction between the government and the publics, where the relationship formed and not the final outcome is the most important consideration. This relationship (formation and viability) is affected by the publics’ perception of the communicating country’s brand and reputation.

CONCLUSION

The different elements described in this article—political marketing, public diplomacy and soft power—are all tied to realizing political outcomes in the form of policy. Political marketing and public diplomacy are (or should be) focused upon forming relationships with target publics to stimulate joint value production through giving the target public a sense of ownership and inclusiveness in various projects and interactions. This is building toward the accumulation of soft power, where an actor is able to attract and co-opt target publics willingly to do what they wish. It should be pointed out that these mediums of communication and influence are no substitute for poor/ill-conceived policy and are ineffective when words and deeds do not match.

However, soft power is a long-term project that is hard to create and easy to lose. The results may not be noticeable for some considerable time. This article focuses on NGOs, which according to Cull’s five elements of PD, falls very much under the category of advocacy. NGOs are intended to provide a greater perceived sense of legitimacy through a less obvious link to the Russian government, which suffers from international legitimacy issues linked to their poor image and reputation. Such organizations are also potentially good relationship builders, and may possess the necessary skills, networks and local knowledge that are superior to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. A set of strong ethics and values are expressed, such as friendship, partnership, nonintervention/interference in other’s affairs and Christian heritage. The notion of sovereign democracy serves as a form of political ideology, as a kind of shield against Western pressure and interference in other countries’ internal affairs.

NGOs also provide a ready means for a more personal face-to-face form of communication and interaction. They are a good platform for advocacy, possessing the means to publish, disseminate material and hold public events. Through these means there is potential to communicate a strategic message and to engage (and possibly influence) publics. The Russian NGOs detailed in the previous section have broadly defined their market position as a challenger. That is to challenge criticism from largely Western countries concerning issues such as democracy and human rights, but also to criticize other countries’ actions (such as “humanitarian intervention”). Therefore, the strategic posture of these organizations is in opposition to what can be defined as being Western hegemony in international affairs.

The competitive position is to communicate an opposing set of values, such as the notion of sovereign democracy and the idea that the state is still the best unit of interaction within the sphere of international relations. Approaches to communication include both positive and negative campaigns. An example of the negative campaign aspect is, for example, the Institute for Democracy and Cooperation that challenges Western double standards in terms of issues with democracy and human rights. Other NGOs (Positive Russia and Historical Memory Foundation for example) attempt to address Russia’s vulnerable points—negative public opinion, stereotypes and controversial periods in history. Not all NGOs are equal, the Gorchakov Foundation appears to play a coordinating role within Russian PD. It does this through funding other NGOs and encouraging interaction and cooperation between Russian and foreign partners.

One of the primary stated motivations for engaging in PD is that Russia considers itself as having an unjust and incorrect international image and reputation. This dictates that some effort needs to go in to trying to rehabilitate that image. The other activities are clearly geared towards specific policy objectives, such as the Caucasus Dialogue program of the Gorchakov Foundation. Ultimately, there is no transfer of ownership in the process, success is also ultimately determined not by singular policy successes, but by the creation of durable relationships with various foreign publics.

Notes

Dolinskiy, A., How Moscow Understands Soft Power, Russia-Direct, 26 June 2013 in Johnson’s Russia List, 2013-#116, 26 June 2013.

From Scammell, M. (1999), Political Marketing: Lessons for Political Science, Political Studies, XLVII, pp. 718–39.

Transaction marketing focuses upon singular purchases and does not build a relationship with its audience. In this scenario, the communicator tries to win the target audience over repeatedly, without regard to any previous contact and/or transactions (Johansen, Citation2005: 88).

Koshkin, P., Soft Power: What Can Russia Learn from the US Experience? Russia Beyond the Headlines, http://rbth.ru/blogs/2013/04/03/soft_power_what_can_russia_learn_from_the_us_experience_24621.html, 3 April 2013 (accessed 8 April 2013).

Zlobin, N., “Soft Power”: Russian Priority in New World Order, Russia Beyond the Headlines, 31 May 2013, in Johnson’s Russia List, 2013-#99, 31 May 2013.

1) ⊓чельников, Л., России нужна “мягкая сила”, Российская газета, http://www.rg.ru/2012/11/01/sila-site.html, 1 November 2012 (accessed 5 June 2013).

2) МИД: Использование “мягкой силы” способствует реализации интересов РФ, Российская газета, http://www.rg.ru/2012/10/31/gatilov-anons.html, 31 October 2012 (accessed 5 June 2013).

Putin, V., Speech at a Meeting with Russian Ambassadors and Permanent Representatives in International Organizations, http://eng.kremlin.ru/transcripts/4145, 9 July 2012 (accessed 17 July 2013).

Filimonov, G., Russia’s Soft Power Potential, Russia in Global Affairs, http://eng.globalaffairs.ru/number/Russias-Soft-Power-Potential-15086, 25 December 2010 (accessed 12 June 2013).

Dolinskiy, A., Why Russia is Losing its Soft Power Quest, Russia Beyond the Headlines, http://rbth.ru/opinion/2013/02/05/why_russia_is_losing_in_its_soft_power_quest_22521.html, 5 February 2013 (accessed 8 April 2013).

United Nations, Economic and Social Council, Open-Ended Working Group on the Review of Arrangements for Consultations With Non-Governmental Organizations; Report of the Secretary-General, U.N. Doc. E/AC.70/1994/5 (1994).

America’s Ambassadors? The NGO Role in Public Diplomacy Discussed at InterAction’s 2010 Forum, InterAction, https://www.interaction.org/article/interaction-forum-2010-recap-americas-ambassadors-ngo-role-public-diplomacy, 3 June 2010, (accessed 12 June 2013).

1) Zarrati, S., NGOs as Protagonists in 21st Century Diplomacy, ThinkIR, http://www.thinkir.co.uk/ngos-as-protagonists-in-21st-century-diplomacy/, 7 January 2013 (accessed 12 June 2013).

2) The Importance of Non-Governmental Organizations in the New Public Diplomacy, The New Diplomacy D, thenewdiplomacyd.blogspot.se/2010/11/importance-of-non-governmental.html, 29 November 2010 (12 June 2013).

To read this document please go to http://www.mid.ru/brp_4.nsf/0/76389FEC168189ED44257B2E0039B16D.

Full name Federal Agency for the Commonwealth of Independent States Affairs, Compatriots Residing Abroad, and International Humanitarian Cooperation (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Russian Federation—is a federal executive authority, performing functions for rendering public services and management of state property in the area of providing for and developing the international relations of the Russian Federation and CIS member states, other foreign states, as well as within the field of international humanitarian cooperation (from http://www.linkedin.com/company/rossotrudnichestvo. Website found at http://rs.gov.ru/.

Lavrov, S., Speech to Representatives of Russian NGOs Interacting With Ministry of Foreign Affairs on International Topics, Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, http://www.mid.ru/bdomp/brp_4.nsf/e78a48070f128a7b43256999005bcbb3/480a438af0b73ddb44257b26003ee019!OpenDocument, 4 March 2013 (accessed 12 June 2013).

Shakirov, O., Russian Soft Power Under Construction, e-International Relations, http://www.e-ir.info/2013/02/14/russian-soft-power-under-construction/, 14 February 2013 (accessed 12 June 2013).

Russia builds up its public diplomacy structures, Centre for Eastern Studies, http://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/eastweek/2010-02-10/russia-builds-its-public-diplomacy-structures, 10 February 2010 (accessed 26 January 2013).

Uniting Efforts of International Experts in Combating Non-Communicable Diseases, Equal Right to Life, http://www.ravnoepravo.ru/en/news/news/more/article/uniting-efforts-of-international-experts-in-combating-non-communicable-diseases-1259/, 10 January 2013 (accessed 26 January 2013).

Roundtable on Public Diplomacy, Russian International Affairs Council, http://russiancouncil.ru/en/inner/?id_4=512, 21 June 2012 (accessed 26 January 2013).

What Is RIAC? General information, Russian International Affairs Council, http://russiancouncil.ru/en/about-us/what_is_riac/, accessed 26 January 2013.

Ibid.

Обращение исполнительного директора фонда (Message from the Executive Director of the Foundation), О Фонде (About the Foundation), Gorchakov Public Diplomacy Foundation, http://gorchakovfund.ru/about/, accessed 26 January 26, 2013.

Мисссия и Задачи (Mission and Objectives), Gorchakov Public Diplomacy Foundation, http://gorchakovfund.ru/about/mission/, accessed 26 January 26, 2013.

Lavrov, S., Speech to Representatives of Russian NGOs Interacting With Ministry of Foreign Affairs on International Topics, Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, http://www.mid.ru/bdomp/brp_4.nsf/e78a48070f128a7b43256999005bcbb3/480a438af0b73ddb44257b26003ee019!OpenDocument, 4 March 2013 (accessed 12 June 2013).

About Us, Foundation, Historical Memory Foundation, http://www.historyfoundation.ru/en/about.php (accessed 15 July 2013).

Russian NGO to Monitor US Democracy, The Other Russia, http://www.theotherrussia.org/2008/01/26/russian-ngo-to-monitor-us-democracy/, 26 January 2008 (accessed 15 July 2013).

The Institute of Democracy and Cooperation, http://www.idc-europe.org/en/The-Institute-of-Democracy-and-Cooperation (accessed 16 July 2013).

Теслова, Е., имиджем России в Великобритании займется соавтор лутина, известия, http://izvestia.ru/news/553268, 9 June 2013 (accessed 14 July 2013).

REFERENCES

- Coombs, W. T., and S. J. Holladay. 2010. PR Strategy and Application: Managing Influence. Singapore: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Cull, N. J., 2009. Public Diplomacy: Lessons from the Past. Los Angeles: Figueroa Press.

- Cwalina, W., A. Falkowski, and B. I. Newman. 2011. Political Marketing: Theoretical and Strategic Foundations. New York: M. E. Sharpe.

- Heine, J. 2006. On the Manner of Practicing New Diplomacy. Waterloo, Canada: The Centre for International Governance Innovation Working Paper Number 11.

- Johansen, H. P. M. 2012. Relational Political Marketing in Party-Centred Democracies: Because We Deserve It. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Johansen, H. P. M. 2005. “Political Marketing.” Journal of Political Marketing 4 (4):85–105.

- Jowett, G. S., and V. O’Donnell. 2012. Propaganda and Persuasion, 5th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- L’Etang, J. 2011. Public Relations: Concepts, Practice and Critique. London: Sage Publishing.

- Leonard, M., C. Stead, and C. Smewing. 2002. Public Diplomacy. London: The Foreign Policy Centre.

- Lilleker, D. G. 2011. Key Concepts in Political Communication. London: Sage.

- Lord, C. 1998. “The Past and Future of Public Diplomacy.” Orbis 42 (1):49–72.

- Melissen, J. 2011. Beyond the New Public Diplomacy. The Hague: Clingendael Paper Number 3.

- Melissen, J., (ed.). 2005. The New Public Diplomacy: Soft Power in International Relations. New York: Palgrave-MacMillan.

- Newman, B. I. 1999. The Mass Marketing of Politics: Democracy in an Age of Manufactured Images. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Nye, J. S. 2004. Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics. New York: Public Affairs.

- Nye, J. S. 2011. The Future of Power. New York: Public Affairs.

- Ormond, R. P., S. C. M. Henneberg, and N. J. O’Shaughnessy. 2013. Political Marketing: Theories and Concepts. London: Sage Publishing.

- Payne, J. G. 2009. “Reflections on Public Diplomacy: People to People Communication.” American Behavioural Scientist 53 (4):579–606.

- Seib, P. 2012. Real-Time Diplomacy: Politics and Power in the Social Media Era. New York: Palgrave-MacMillan.

- Seib, P. (editor). 2009. Towards a New Public Diplomacy: Re-directing U.S. Foreign Policy. New York: Palgrave-MacMillan.

- Simons, G. 2011. “Attempting to Re-Brand the Branded: Russia’s International Image in the 21st Century.” Russian Journal of Communication 4 (¾):322–350.

- Snow, C. (Jr). 2006. “Public Diplomacy Practitioners: A Changing Cast of Characters.” Journal of Business Strategy 27 (3):18–21.

- Snow, N. 2010. “Public Diplomacy: New Dimensions and Implications.” In Global Communication: Theories, Stakeholders and Trends, edited by Thomas, L. McPhail, 84–102, 3rd ed. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Snow, N., and P. Taylor, (eds) 2009. Routledge Handbook of Public Diplomacy. New York: Routledge.

- Szondi, G. 2008. Public Diplomacy and Nation Branding: Conceptual Similarities and Differences. Discussion Papers in Diplomacy: Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael. Retrieved from http://ts.clingendael.nl/publications/2008/20081022_pap_in_dip_nation_branding.pdf

- Zhang, J., and B. C. Swartz. 2009. “Toward a Model of NGO Media Diplomacy in the Internet Age: Case Study of Washington Profile.” Public Relations Review 35:47–55.