Abstract

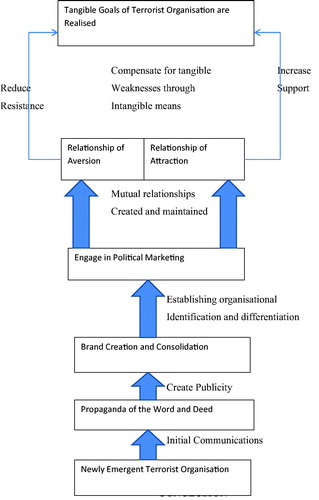

This article investigates how the infamous terrorist organization Islamic State (ISIS) uses branding and political marketing as means to increase their intangible value and assets in order to influence their tangible (operational) capacities. In order to investigate the logic of a terrorist organization as a political actor a perspective of political communication is applied as a means to understand more clearly the propaganda of the word and the propaganda of the deed. A systematic communication approach is used to raise awareness of the ISIS brand in order to differentiate the organization and to create a greater sense of credibility and authenticity in an increasingly crowded marketplace of terrorist organizations seeking for attention, support, and fear. Aspects of political marketing are used in order to create sets of relationships of attraction and avoidance with different target audiences. The 15 issues of the magazine Dabiq are examined and analyzed within this approach. However, intangible communication and tangible realities do affect each other. This is evident when there is a swing from military victories to military defeats, which impacts on the quality and quantity of communicational materials produced by ISIS.

Introduction

Terrorism was traditional conceived and viewed as being a phenomenon that was to be understood through legal and security frameworks. This has been gradually changing with time and focus of the debates as events and processes of terrorism in the late 20th Century and early 21st Century unfold. Academics have begun to apply different lenses from communication sciences in order to better understand terrorists and terrorism (Matusitz Citation2013; Nacos Citation2007; Tuman Citation2010). As the development of New Information Technologies have progressed so has the reach of terrorist groups to the wider public, “social media enables terrorists to communicate radicalizing messages to a far wider circle of potential adherents than they could have reached with traditional media. Previously, radicalization required personal contact with someone who could provide materials, ideological grooming, and connections to wider jihadist networks” (Kean and Hamilton Citation2018: 4). This follows from the long-established axiom “publicity is the oxygen of terrorism,” which has led to an assumption of a symbiotic relationship existing between terrorists and journalists (Matusitz Citation2013: 54–57). The rise of terrorist groups such as al Qaeda and Islamic State (ISIS) has demonstrated the relevance of understanding the motivations and mechanisms of terrorists through pertinent academic communication disciplines.

This study of ISIS and Dabiq magazine is both important and relevant from the points of view that it clearly illustrates and demonstrates the effects of a changing and evolving role of brand reputation and political marketing communication in the face of emerging challenges in the tangible environment. It [Dabiq] is a laboratory to observe how the tangible and intangible elements interact and influence each other in an environment of armed conflict. The reason for the use of “laboratory” is in reflection to the fact that this specific example has seen the full life of Dabiq—in the birth, life, and death of this mechanism of propaganda and political marketing—in a relatively short space of time. This provides an opportunity to observe and dissect those factors that affect the viability of such publications. However, is it even possible to consider or contemplate analyzing such an abhorrent terrorist organization as ISIS through the lens of branding and political communication or is this a step too far? Certainly it may be considered to be somewhat uncomfortable for some people to consider using the academic frameworks that give meaning and understanding to our understanding of the political and commercial frameworks that are central to the functioning of contemporary modern society. There are some good reasons for pursuing this approach though. These terrorist organizations have proven themselves to be very adept at simultaneously communicating to different groups and interests, which has provoked both policy-oriented and academic interest (Heck Citation2017; Holbrook Citation2014). Leading brands of terrorist organizations, such as ISIS, have been very successful in communicating their political cause through branding and marketing strategies.

Taking the above into consideration, there certainly seems to be an intellectual divide and dilemma posed by a “revolutionary” organization that communicates politically and socially nihilistic values via contemporary technological and communicational means. This has left some to ponder how it is possible for such an organization to be able to communicate an attractive message that lures people away from open societies to a closed society. How does ISIS make use of their brand via political marketing strategies, and does this change with fortunes on the battlefield?

This article will initially understand terrorism through the perspective of it being a political activity, before shifting to a brief summary of ISIS and its history. Terrorism as a political activity will be briefly considered before moving to content on understanding how propaganda of the word and deed is used in order to draw in the target audience into an emotionally reciprocal relationship between the audience and the messenger. Then, the article will move to engage in defining and understanding branding and political marketing from a theoretical perspective, although with significant pragmatic implications. ISIS and how they manage their specific organizational brand through Dabiq will be tracked and analyzed, with focus on how the quality and quantity of the message and its delivery was influenced by physical events on the battlefield.

Terrorism as a Political Activity

Definitions of terrorism are rhetorically unstable and are discursively contested, which is affected by and depending on the definer’s professional, political, academic, or ideological perspective. There are some 200 different definitions of terrorism in existence, and it is a highly politically contested word (Matusitz Citation2013: 3; Moeller Citation2009; Tuman Citation2010). Given the lack of acceptance of a universal definition, terrorism can be defined as the use of violence to create fear for political, religious, or ideological reasons. “The terror is intentionally aimed at non-combatant targets, and the objective is to achieve the greatest attainable publicity for a group, cause or individual” (Matusitz Citation2013: 4). The current global political hegemonic power, which influences how the lived and representational aspects of the world are communicated and received, also produces resistance and challenges to that order (Jayyusi Citation2012: 38). Therefore, some see terrorism as a reaction against the modernization of society, together with the new norms and values that the change symbolizes and represents (Dingley Citation2010). This is reflected in the nature and timing of targets selected for attack by terrorist groups.

In terrorism, we have seen that symbolism and rhetorical meaning may be found in the specific targets of the terror act whether situated in the context of time or location – both of which significantly contribute to the manner in which we construct what terrorism means for us (Tuman Citation2010: 106).

Thorne (Citation2005: 597) observed that “terrorist organizations are information oriented and politically savvy.” Terrorism is linked to the politics of fear (Altheide Citation2006), which is in effect form as rituals of control to direct public attention in order to be able to politically exploit the sensation of fear and the desire of the target audience to reduce the psychological discomfort. There is a need for terrorist organizations to “compensate” for their military weakness to the forces they oppose through projecting images of themselves as being simultaneously a serious security challenge and a source of inspiration to divergent audiences that may solidify their reputation and brand. Acts of violence committed by terrorist is a calculated political act that attempts “to influence the beliefs of their enemy and the population they represent or wish to control.” Furthermore, the act is intended as a means to “signal their strength and resolve in an effort to produce concessions from their enemy and obedience and support from their followers” (Kydd and Walter Citation2006: 78). Not all terrorist organizations are successful in converting intangible communication to tangible results. One of the terrorist groups that managed to achieve this in a relatively short space of time was the Islamic State (aka DAESH, IS, ISIL, and ISIS). But who are they?

Brief ISIS Background

Islamic State (also known as IS, ISIS, ISIL, and Daesh) first gained international prominence in 2014 when it started to defeat and drive Iraqi government forces out of key cities in Western Iraq, such as Mosul (Carter, Alkhshali, and Capelouto Citation2014). However, the organization’s origins can be traced back to the year 1999, when it was known as Jama'at al-Tawhid wal-Jihad, during which time it pledged allegiance to Al Qaeda and was involved in the joint struggle in Iraq after the US-led invasion of the country in 2003 (Zelin Citation2014). ISIS is regarded by some as a theocracy, proto-state and a Salafi or Wahhabi group (Bellanger-McMurdo Citation2015; Crooke Citation2014; Wood Citation2015). ISIS was run by its leader and spiritual head, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, who keeps a very low public profile (Mojon Citation2017). Under Baghdadi ISIS has grown considerably in terms of tangible territory, especially after the declaration of the Caliphate on 29 June 2014 (Collard Citation2015), and in brand reputation. This meant that ISIS made the transition from the traditional “non-territorial” terrorist group to a territorial one—actually possessing and governing a tangible area of land and people as well as the considerable intangible presence in cyberspace.

A moral panic has been created by the nature of the ISIS appeal in face of the assumed superior values of neo-liberalism’s globalization and multi-culturalism. This appeal is seemingly rather broad and diverse, with recruits and supporters being drawn from across the globe. This has led to the organization being deemed as being a global threat (Carafano Citation2016). However, the recent military setbacks that ISIS has been experiencing in Iraq and Syria with the loss of its physical territory have caused some to question whether ISIS is in a state of collapse. It was noted in a study that propaganda production increased in terms of quantity and its outreach with the military successes of 2014–2015, with the onset of military defeats the propaganda quantity has decreased and the priority target audience is an internal one (Clarke Citation2017). Other predictions have included the notion that ISIS may return to its guerrilla roots after the collapse of its Caliphate (Coker, Schmitt, and Callimachi Citation2017). This demonstrates that tangible effects can influence intangible elements as much as it can vice versa. To be successful in priming and mobilizing audiences in fear or awe or admiration and so forth, there needs to be a psychological environment created that supports the emotionally resonating messages.

Propaganda of the Word and Deed

The definition of the word propaganda is every bit as controversial as its use. This word has associations of manipulation, brain washing, use by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, now more recently the presumed and projected powers of ISIS propaganda is the cause of fear among publics. It seems to superficially represent a practice and goal that is utterly alien and contra to a free and democratic society (Taylor Citation2003). Some initial definitions to depart from can include, “propaganda is organized persuasion and involves the dissemination of biased ideas and opinions, often through the use of lies, deceptions, distortions, exaggerations, and censorship” (Conserva Citation2003: iii). Taylor defines propaganda as “the deliberate attempt to persuade people to think and behave in a desired way. […] the conscious, methodical and planned decisions to employ techniques of persuasion designed to achieve specific goals that are intended to benefit those organizing the process” (Taylor Citation2003: 6). When considering the word propaganda, it not only involves tangible acts, but also involves an intangible expectation.

The word propaganda has since evolved to mean mass “suggestion” or “influence” through the manipulation of symbols and the psychology of the individual. Propaganda involves the dextrous use of images, slogans, and symbols that play on our prejudices and emotions; it is the communication of a point of view with the ultimate goal of having the recipient of the appeal to come to “voluntarily” accept this position as if it were his or her own” (Pratkanis and Aronson Citation2001: 11).

The message needs to be carefully considered, but also the wider political and social environment, if the goals and objectives of the messenger are to stand any chance of success. Patrick (Citation2012: 10) argues that “more than a mere set of techniques, propaganda is situational in nature. It is an organized bid for the right to interpret meaning in a given set of circumstances.” The right message needs to hit the right audience at the right time and in the right circumstances. It is effects are meant to increase the perception of a simple subjective reality, but the process of deployment is complex. This is demonstrated when the battlefield fortunes of ISIS begin to turn by late 2015, the realities of the physical battlefield environment affected the quantity and quality of propaganda and communications as shall be seen further on in this article.

Language is a critical aspect of the process with its ability to shape an emotional perception of a projected reality. “The language in which ideas are expressed is critical to defining a cause or strategy, and sets forth the story, plot, and narrative that underlies a strategy as well as its themes and messages” (Farwell Citation2012: 57). However, there are other aspects to consider in the process.

One of the other tools to be used is that of symbols and symbolism. A symbol has embedded in it a number of associated values and norms; it is an emotional rallying point that enables the priming and mobilization of an audience. A symbol can be an idea, an object or a person. “Symbols matter especially for identity politics, and in today’s world, identity motivates political activity. […] Symbols can provide points of reference that ground a campaign” (Farwell Citation2012: 79). Even though symbols can guide and provide a reference point, it should be noted that people interpret symbols differently; it is far from being a uniform process. Symbols are a critical component of creating a brand identity for a terrorist organization, such as ISIS, which in turn is the basis of forming the expectations as to the nature and quality of political relationships that are formed with various stakeholder groups. Potent and powerful symbols to publics are key historical events, their propagation and perception, in the consciousness of publics.

Historical events form a central part of a society’s collective memory through a shared narrative and experience. Exceptional historical moments, iconic events, play a role in shaping values, norms and morals by communicating ideas. The ideas are an “instruction” to members of a society on acceptable or unacceptable thoughts and actions, which is influenced by media coverage of those iconic events. This creates a myth-like aura that surrounds the moment, which can be exploited for different purposes. “Iconic events take shape in different ways. From the moment they occur, certain events seem to occupy a disproportionate space in the culture. The media fixates on these events, which in turn, alerts the public to the event’s unique significance. The press thus engages in a tautology: the event is historically exceptional and it gets endless coverage, thus reinforcing its historical exceptionality” (Leavy Citation2007: 3). There is a certain apparent media “obsession” when it comes to the coverage of ISIS in media content, and particularly in news and documentaries, which seemingly gives the groups a greater sense of reach and power than it actually physically possesses in reality. However, it should be noted that people react to what they deem as reality, regardless of the actual situation.

An event that can be transformed into an Iconic event, combined with the application of political marketing and propaganda, is intended to bring about an emotional logic in the target audience. Specifically, it is intended to induce outrage in the said audience in order to induce an information environment where pathos is dominating.

Outrage sidesteps the messy nuances of complex political issues in favour of melodrama, misrepresentative exaggeration, mockery, and improbable forecasts of impending doom (Sobieraj and Berry Citation2011: 20).

In the case of ISIS, propaganda is designed to catch the emotional attention of their target audience by seemingly being able to fulfill an emotional need in an individual or a group. However, in order to snare those individuals and groups a mutual and reciprocal social and political relationship needs to be formed. Even if this cannot be formed physically, it should be managed on a psychological basis. Therefore, brand recognition and resonance of a terrorist organization could make a marked difference through being able to leverage its intangible assets (brand, reputation, recognition, belief, fear, and loyalty) into tangible pursuits of achieving physical political goals, such as the establishment of a physical entity (for example, a Caliphate) to the psychological one. The use of propaganda is intended to psychologically prepare the target audiences for suggestion and an emotionally resonating relationship that is created with a group such as ISIS through the skilled use of branding and political marketing.

Branding

Branding is a standard philosophy and practice in the contemporary business and political environments. It is an indispensable aspect of organizational activity, depending on the conceptual underpinnings and the execution of the practical approach; it can be the difference between success and failure in attaining organizational goals and objectives. In way of a basic definition of the term and its implications, the following provides an overview. “Branding is the process by which companies differentiate their products from their competition. In developing a unique identity, which may include a name, packaging and design, a brand is developed. In developing and managing this unique identity, the branding process allows organizations to develop strong emotional and psychological connections with a product, goods, or service. This in turn, eases the purchasing decision. Branding affects stakeholder perceptions and the marketing task is to ensure these perceptions are positive” (Franklin et al. Citation2009: 33).

A brand is a significant step in the road to creating and maintaining an enduring mutually reciprocal political relationship between the messenger and the audience. Newman (Citation2016: 92) understands brand, from the point of view of political application as a mechanism that “may connect voters via the policies and issues they represent as well as through the personality traits they possess.” ISIS deliberately avoids using the symbolic face of its leader in the brand of the organization, they do however, use his writings as a source of legitimacy. Instead of using a key public personality ISIS chose the path of symbolic ideological and policy appeal as the basis of their brand strength. This differs markedly from Al Qaeda that used Osama bin Laden as a key element in the brand equity of the organization. Given the broad appeal of ISIS communications in terms of the types of people it attracted to its cause, the strategy seems to have been appropriate. A series of steps are used by marketers in order to embark on establishing a brand. The first step is to build awareness through communication concerning a particular product or service on offer, which is likely to increase engagement and interaction. Step two concerns positioning of the product or service, once the consumer is aware of it. This is an attempt to differentiate it from its competition. The third step is about establishing a brand after awareness and positioning are implemented. Then automatic associations and assumptions are connected to the brand of a particular product or service (Newman Citation2016: 112). This has occurred for ISIS, which is often credited with terrorist attacks automatically by the mass media as they are perceived as the world’s number one terrorist brand, thus the associated has been formed.

There are three different aspects to be examined when evaluating the strength of brand value. Differentiation is used to distinguish a product, service or organization from competing brands, and thereby be better able to position itself more ideally to enable better reach and connection with the target audience. A brand’s visual identity is a key aspect in helping an audience to better identify the difference and believe in it. Credibility of a brand is an icon of trust and credibility, with the intention of helping to develop a loyal following. An organization’s credibility is achieved by its ability to live up to its promise(s). Authenticity is gained by matching words and deeds. Efforts are also needed to draw in a wider audience and not just those individuals that are directly affected or concerned by an issue (Matusitz Citation2015: 241). The aspects identified above are concerning the pursuit of brand management.

Brand management is a communication function that consists of examining and planning how a brand should be positioned in the world, to what type of audience the brand should be targeted, and how ideal the reputation of the brand should be preserved. Brand management is an example of public communication. Public communication is a purposive effort to inform or affect the behaviours of large audiences within a specific set of time using a coordinated set of communication activities (Matusitz Citation2015: 241).

There are a number of approaches that can be taken to branding an organization or country: country of origin (COO) (stereotype); product-country image (national identity); made-in country image (national characteristics); and country image effect. At its very simplest level, an organizational or country logo is an example of COO a more developed stage of branding would be to assign the name for a country or organization, for example the ‘Axis of Evil’ (which mixes branding and political marketing) (Fan Citation2006: 6–7). Terrorist organizations also make use of these communicational tools. COO by terrorist organizations has come under increasing focus, which has included efforts to systematically break down the images, colors, and typographies of logos. Such efforts have demonstrated that terrorist groups perceive themselves as brands and they use symbolic imagery in order to communicate their goals and aims (Beifuss and Bellini Citation2013). This can be seen in the various communicated branded aspects such as the name of the organization, uniforms worn, flags and logos, identified leadership of the group, and mediated acts.

It can be stated that ISIS has been quite successful in establishing and maintaining their global brand and reputation. One of the indications of this success is how well their brand symbols and logos are recognized by the global publics. This was clearly seen in 2016, when ISIS symbols and logos had a higher profile and were more widely recognized than those of the Vatican! (Leaders in Nation Branding Citation2017) This situation provides a good hint at how the organization has managed to develop the brand awareness in order to make it well-known and recognized. There are also other hints at their success in the branding and marketing of their organization, the 2017 PEW Centre global security threat perception poll that was conducted among 38 countries worldwide, the terrorist organization topped the list in 18 of those countries as the greatest perceived security risk and was the overall leading source of risk against the other seven choices offered (Poushter and Manevich Citation2017).1 It also means that ISIS have managed to position themselves as the global premier terrorist organization in a “class” of their own that is well above other competing terrorist organizations. The results of this poll provide a demonstration of a brand reputation having an impact upon operational security aspects, even though the physical capacity of the organization to effectively physically carry out threat imagined by the global publics is highly questionable. Thus the brand and reputation of significant security threat has been effectively communicated and conveyed intangibly and well beyond what is tangibly possible. The World PR Global Leadership Ranking 2018 report highlights the evident link between the tangible and intangible elements of a brand. “The Islamic State drops down both Western Perception indices (cumulative and past 12 months), reflecting its military defeat in Syria and Iraq and its resulting diminished physical presence” (World PR, Citation2018: 3). This suggests that there is a connection between brand and organizational performance, when ISIS does well on the physical and informational battlefield there is a boost to the potency of the brand and a “positive” influence of audience perception of the organization’s effectiveness. However, in a reversal of fortunes in the physical battle and the inability to sustain the informational efforts, ISIS is considered much less effective and powerful as a political brand and a terrorist organization.

Zaharna has noted that within the practice of public diplomacy political actors seek to dominate the informational battlefield through controlling and winning the narrative. Social media is one of the sites of this struggle where competitors seek to win decisively. It is argued that “narrative contests are inherently identity battles in that narratives contain intertwined elements of identity and image” (Zaharna Citation2016: 4407). The matter is how the communicating actor expresses and projects themselves and their goals and experience of living the brand identity. This is very noticeable in ISIS’s communication strategy that is employed by Dabiq, of a binary set of diametrically opposed sets of brand identities and images, of heroes (ISIS) and villains (the enemy).

Political Marketing

The focus of this particular section is on political marketing, but not from the traditional perspective of the discipline. Traditionally, when applying political marketing, the objective normally involves making a political product more attractive in the political market. As a first step though, it is necessary to recap the current state of art on objectives of political marketing and especially as it relates to the political persona. As an initial point of departure, political marketing currently assumes an active form of communication that engages communicators and a target audience in a mutually beneficial relationship. These aspects and elements are stressed in different definitions of the term and practice of political marketing.

Political marketing is a perspective from which to understand phenomena in the political sphere, and an approach that seeks to facilitate political exchanges of value through interactions in the electoral, parliamentary and governmental markets to manage relationships with stakeholders (Ormrod et al. Citation2013: 18).

[Political marketing involves] the processes of exchanges and establishing, maintaining, and enhancing relationships among objects in the political market (politicians, political parties, voters, interest groups, institutions), whose goal is to identify and satisfy their needs and develop political leadership (Cwalina Falkowski and Newman Citation2011: 17).

Scammell (Citation2014: 4) warns of an existing disconnect between the theoretical ideals and actual practice. Within the framework of a terrorist organization’s application of these goals, it is not necessarily solely about the group’s popularity, but more so about their public visibility and resulting reputational brand as a means to connect and form relationships with different constituencies. Emotions play an important role in the public’s perception and evaluation of key political figures. “Politics comes down to our gut reactions about politicians and their ideas. The emotions that we feel when we watch leaders are an integral part of how we judge politicians” (Newman Citation1999: 89). Within this emotional setting emerges the notion of a brand. “Branding is about how a political organization or individual is perceived overall. It is broader than the product; whereas a product has a functional purpose, a brand offers something additional, which is more psychological and less tangible” (Lees-Marshment Citation2009: 110). Marketing a brand helps to create and determine the niche for the object or subject within the wider environment. As has been stated on previous occasions, ISIS seeks a prominent place from the competing terrorist brands through a politically marketing strategy that positions its reputation advantageously

Strategic positioning of individual political image and brand actors within the broader political market is important in determining the success or the failure of an individual politician. “It relies principally on competition as the ultimate driver of action at all levels of the ‘market’” (Johansen Citation2012: 40). The value and resonance of that brand and image of a political actor’s effectiveness and popularity is influenced not only by their individual projected qualities, but also the perceived qualities of their competitors. Cwalina et al. (Citation2011: 158–159) “consider emotions as a separate element not only influencing voters’ behaviors, but also shaping the way of perceiving a candidate’s agenda and receiving political information broadcast by the media.” Thus the aspects of emotion, communication and perception act on and influence each other in a contextual relationship. “In covering the prevailing power struggle, there is typically an increased emphasis on the actors’ appearance, autobiography, and leadership qualities, as well as their policies. This personality-based coverage has both been a response to and an encouraged the use of a coterie of media specialists” (Stanyer and Wring Citation2004: 2). ISIS as an organization has managed this aspect quite well, by rather rapidly becoming recognized globally as being the world’s “premiere” terrorist organization, but with multiple types of political relationships formed with opponents and supporters simultaneously.

The above mentioned quote demonstrates the importance of a projected communication-based perception to shape the quality of an actor’s intangible qualities (and implied tangible qualities and abilities). Castells notes that politics is largely based upon socialized communication and its capacity to influence peoples’ minds. In this regard, the distribution of political power is being determined by the media. “In our society, politics is primarily media politics. The workings of the political system are staged for the media so as to obtain the support, or at least lesser hostility, of citizens who become the consumers in the political market” (Castells Citation2007: 240). However, the same may also be feasible too, where elements of the political system are staged in the media to create the greatest amount of hostility and resistance to a political system and their policies. There also needs to be an understanding how the marketing aspect is operationalized.

When referring to the marketing revolution in politics, Bruce Newman states that a number of observable lessons can be drawn from the Obama election campaign. One of these was the use of technology strategically. Technological leaps in the means of communications have permitted political relationships to be created and maintained with stakeholders, which can make the conversation seem to be more authentic and meaningful for those following it (Newman Citation2016: 62–76). Modern Information Communication Technology is also the key to Newman’s fourth lesson, which concerns the development of a unique brand identity. This concerns the problematic issue of how to present all of the products and services as a single and unified brand. “This also called for the careful development of campaign slogans, logos, and colors that were coordinated strategically” (Newman Citation2016: 91). Certainly, ISIS has been very adept to using the internet as a means to rapidly and effectively disseminate their message and brand, which has been noted by numerous observers (Holbrook Citation2014; Melki and Jabado Citation2016; Simons Citation2016, Citation2017; Spencer Citation2017).

These help to define emotionally resonant symbols that can be used to attract an audience into a political relationship with the communicator. There are also other political mechanisms that can be deployed in order to increase political attractiveness and legitimacy. Within the subject framework and the context of this article, one of the aspects that need some consideration is the role and marketing of ideology. Understanding the word “ideology” to be a loaded and contested term, Savigny (Citation2008: 65) understands it as “systems of shared beliefs and internally consistent sets of ideas.” Ideology is understood as being a self-legitimating function that excludes other systems and sets of beliefs. Although in the wake of the end of the Cold War, the role of ideology in politics was played down and became a rather neglected consideration, others saw its gradual re-emergence. Schwarzmantel (Citation2008) challenged the notion of the world having arrived at a “post-ideological consensus.” One of the reasons for his assessment is the newly emerging movements that have positioned themselves as challengers to the dominant neo-liberal political system. Ideology also plays the role of an organizational philosophy and principle for guiding the activities and brand of an organization to both internal and external audiences (Savigny Citation2008: 66). Holbrook (Citation2014: 141) identifies three core components to terrorist communications: (1) communicative aspects of the act of terrorism, (2) relaying ideological tenets, and (3) counter-narrative messages. This is the means for identifying and understanding the contextual positioning of the organization in the wider marketplace of competing organizations.

Although it may appear to be abhorrent to use political marketing as a means with which to make sense of the different types of political relationships between terrorist organizations as ISIS and targeted publics, it does make sense. The process of the creation of the relationships between the various individuals and groups is not necessarily created through reasoned logic, but through emotional resonance that connects with the needs and wants. A lot of focus is on the “negative” relationships between ISIS and individuals and groups that are centered on the emotion of fear and the desire for aversion, which relates to the enemy and no allied segments of the stakeholders. However, another part of the stakeholders focus on creating and maintaining “positive” relationships, which are driven by emotions such as pride, a sense of belonging and therefore related to a feeling of attraction to the group. When ISIS began and quickly expanded and seemed to grow stronger, the primary emphasis was to create communications and a brand that would demoralize their opponents and those they sought to overthrow. At the same time they needed to attract sponsors, people to populate those newly conquered territories, to run the administration and to fight for them. This required a relationship that inspired positive perception and to motivate those individuals to voluntarily engage in what was being asked of them. This simultaneous communication to segmented audiences was achieved through the coordinated use of communications that included slogans, logos, symbols, and actions.

Creating and Managing the ISIS Brand

Method

In addition to analyzing existing literature in terms of academic articles and media products (such as news articles, opinion articles and reports) in order to understand and form a basis of understanding the current knowledge of how ISIS attempts to brand and market itself to different stakeholders, a review of the material communicated by ISIS was conducted. There are some 57 different media content production units within the ISIS organization (Clarke Citation2017), each of which is contributing to developing its brand and reputation, and connecting it to individuals and groups across the planet. This article intends to delve into one of those media units, which will give an indicative result that has been derived by qualitative means. More specifically a qualitative analysis of the content of the ISIS flagship on-line magazine Dabiq was done in order to deconstruct and understand the basis of their political marketing and branding strategy and how the communication focus and style changed with the fortunes of the physical battlefield. Dabiq was specifically selected because it has both a clear beginning and a clear end date, and therefore provides a good test case to witness how the tangible and intangible elements of war interact and affect each other.

Bergström and Boréus (Citation2017) understand texts as a study of power and other social phenomena as the text is considered to be a crucial artefact in making sense of the power relations present. The analysis to follow employs a qualitative analysis of ideas and ideological content. This has a long history within history, philosophy, and political science, where ideologies and ideas are analyzed as a guide to actions and interactions “that make up society with its institutions, social relations and power relations” (Bergström and Boréus Citation2017: 7). This reflects an actor’s intention to either preserve or to change an existing social order. The value of this qualitative approach over a quantitative approach can be understood through the following perspective. Marshall (Citation2002: 68) likened qualitative analysis to painting. A qualitative approach permits the researcher to “constantly change their viewing distance as they work” and as they works towards closer examination and detail patterns are observed and decisions can be made. In total, there were 15 issues of Dabiq published. A list of the issues and their topics discussed are below in . The first issue of Dabiq came out in July 2014. At one stage, Dabiq was even sold by Amazon, until June 2015, when it was withdrawn (Islamic State Magazine Dabiq Withdrawn From Sale by Amazon 2015).

TABLE 1 Issues of Dabiq

In September 2016, ISIS Dabiq was replaced with another online magazine called Rumiyah (Rome in Arabic). The reason for changing the name was due to the liberation of the town of Dabiq from ISIS occupation. The symbolism of the location is found in a prophecy from the 7th Century that an epic apocalyptic showdown between Muslims and Christians would take place there, along with their final victory (McIntyre Citation2016). Therefore, the name of the magazine is a highly politically and culturally symbolic iconic event as defined by Leavy (Citation2007). Thus the tangible loss was insignificant, but the intangible symbolic value of the loss could damage the credibility, reputation and brand of ISIS.

The first issue of Rumiyah appeared in September 2016, the name is a reference to a hadith when Muhammad stated that Muslims would first take Constantinople and then they would take Rome. Information from the Clarion Project website suggests that by August 2017 a total of 12 issues had been published.2 However, this magazine will not be studied or analyzed in this particular study. Attention shall now shift to understanding why and how branding is used by terrorist organizations.

ISIS: Creating and Communicating a Brand

Terrorist organizations are highly adept at making use of slick communication to create and maintain awareness of consolidation of their reputation and brand, and in order to form mutual relationships with target groups (Simons Citation2017). One of the successful and dynamically evolving terrorist brands is ISIS. It has an iconic black flag, which bears the Shahada (Muslim declaration of faith) in white, the infamous black uniforms and balaclavas,3 spectacles involving the use of swords as a traditional symbol of Islam (Beifuss and Bellini Citation2013), and the use of various spokespeople via social media communication that is also carried in mainstream media.

The effect of Islamic State penetration on a country’s standing also warrants close attention. Islamic State currently stands at 107 on the Western Perception Index (interest over the past year), which is up 56 from 2015, when we began collecting data on the extremist sect. […] This is undoubtedly due to the media attention focused on the conflict and the terrorist atrocities committed in those countries (Leaders in Nation Branding Citation2017).

ISIS is skilled at communication management practice, its ability to synchronize terrorism tactics with communication strategies to gain access and exposure in mass media serves to strengthen its reputation and brand that in practice means attracting recruits and supporters via resonating cultural values and to repel/deter its enemies (Melki and Jabado Citation2016). ISIS has captured the attention of the mass media, which has in turn drawn some criticism of the result. There is no doubting the skilled ability of ISIS to communicate its message with carefully considered and produced messaging, plus their won 24 h TV-channel (Withnall Citation2015) and merchandise, which has resulted in the creation of a brand that large corporations or governments do. The format in terms of clickbait and attractive material in terms of sensationalism attracts media through the media’s appetite for sensationalistic stories and headlines. This attracting media coverage, which in turns drives public perception and opinion to the point where 90% of Americans polled believe that ISIS poses a threat to the United States (Norton 2015). Thus, media hype that uses the coverage of ISIS propaganda and informational products drives public paranoia. Media begin to fulfill the role of an amplifier and an echo chamber for ISIS messaging. Attention and coverage by mass media tends to help with the stages of branding, especially the first step of building awareness and the second stage of positioning the terrorist brand. This enables the third and final stage of establishing a brand much easier for ISIS. Journalists and mass media pay a lot of attention to the issue of the ISIS brand, which has generated much news content.

One of the ways of viewing and narrating the ISIS brand is to see it as spreading worldwide with no apparent means of stopping the spread. The spread of ISIS is seen not only as something tangible in terms of the territory seized in Iraq, Libya and Syria, but also intangible in terms of the power and influence people and groups through its propaganda efforts (Khalaf Citation2016; Moutot Citation2016). At other times and instances, the ISIS brand is presented within the framework of some kind of competition, such as a competition between the Al Qaeda brand versus the ISIS brand (a battle of terrorist brands) (Clarke and Metz Citation2016). Other articles tend to question and try and how ISIS is so successful in its brand communication, and especially through the means of social media (Koerner Citation2016). Other stories tend to frame brand within a hierarchy of competition between different brands of terrorism, where ISIS is considered to be a leading and successful brand (Petroff Citation2015; Windrem Citation2014). Other articles appear to try and understand the very nature (Olidort Citation2016; Qureshi Citation2015) and the construction of the appeal (Kirkpatrick Citation2014; Rosenfeld Citation2015) of the ISIS brand and how it is communicated (Mustafa Citation2015; Sheffield Citation2015). Another line of argument and questioning concerns whether the power of influence in ISIS communications is about branding or inspiring people and groups (Juergensmeyer Citation2017). In evaluating the strength of the ISIS brand, the three aspects of differentiation, credibility and authenticity as outlined by Matusitz (Citation2015: 241) appear to have been well developed and thereby creating a strong COO-like approach as defined by Fan (Citation2006: 6–7). But branding is not only about product, placement, promotion, pricing, it is very much about creating a sense of belonging and a relationship between the messenger and the receiver.

Changes in the information space and Information Communication Technologies have permitted organizations, such as ISIS, to bypass the traditional gatekeepers of information and knowledge. There are three significant shifts to note: (1) international affairs is no longer the monopoly of state actors, but also individuals and organizations; (2) power through the communication with and mobilization of stakeholders has shifted more from real world to virtual world; and (3) old media interaction is being superseded by new media, which means a shift from monologic to dialogic forms of interaction (Simons Citation2016). Cwalina et al. (Citation2011: 17) define the process of political marketing as involving the processes of exchanges and building relationships in the political market. This is done through identifying and satisfying the needs of the constituency, which generates and develops political leadership. This is achieved via what Newman (Citation1999: 46) terms as having a gut feeling about political movements, branding and marketing nurture the gut feeling by emphasizing the psychological and intangible aspects described by Less-Marshment (Citation2009: 110).

On-line magazines have been used by terrorist groups as a means of communicating to their stakeholders in an increasingly crowded marketplace of competing terror groups, each seeking to have their cause and voice heard above the rest. There have been similarities noted in the approach and style of some of the publications, such as Al Qaeda’s Inspire and Islamic State’s Dabiq. A mixture of negative and positive messaging is used to capture the attention and minds of consumers (Simons Citation2016; Simons and Sillanpaa Citation2016). A means of creating awareness and consolidating the ISIS brand is through the production of propaganda materials, such as Dabiq magazine. The magazine functioned in a two-fold function, it extolled the virtues and triumphs of ISIS and it attempted to promote a common sense of identity. Dabiq made a lot of use from visuals, such as images of the ISIS flag being superimposed over different scenes. The content of the magazine was intended to provoke some sort of response from different target groups. The magazine tries an approach of contrasting opposites, where the West is assigned the role as the “Other.” Interesting, some recent research reveals that while the number of ISIS sympathizers that were proactively trying to disseminate the magazine was relatively small, non-sympathizer accounts in social media (especially Twitter) that posted or reposted material related to the content of Issue 15 of Dabiq in discussions were twice as many (Grinnell, MacDonald, and Mair Citation2017: 8). The effect was to increase the awareness of the cause and ISIS brand.

In spite of the similarities between Inspire and Dabiq, one of the noticeable differences is that Dabiq was almost entirely free of author bylines. This is intended to convey the sense that the writings represent the view of the ISIS brand, rather than of individual authors. In addition, the magazine relied heavily on excerpts from Islamic texts, which was a mechanism to try and present itself as a legitimate religious authority (Robins-Early Citation2016). The magazine Dabiq has been analyzed and found to have three main narratives that support the identity and reputation of ISIS. (1) Muslims have been subjugated by the West, which necessitated the founding of a Caliphate in order to protect Muslims and to fight back. (2) The ISIS interpretation of Islam is “evidence” of its religious superiority and legitimacy, therefore other interpretations are not authentic. (3) A narrative concerning the desire for global dominance by ISIS as a result of the stated religious supremacy of Salafi-Jihadist Sunnis (Heck Citation2017). One observer noted “the common elements of a typically romantic narrative found in many of our classical literary stories in which the heroic righteous ISIS underdog fighter is struggling against an unjust and evil western adversary for a sacred Islamic ideal and a better future in the form of a Caliphate” (Spencer Citation2017: 263).

Dabiq: Creating and managing brands and political relationships

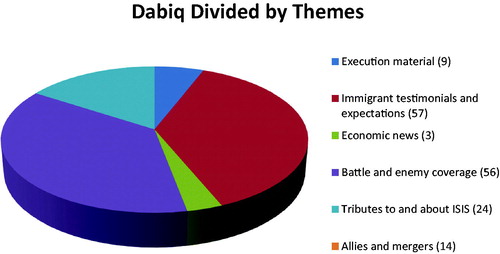

In terms of quantity of genre production, the gruesome trademark of ISIS execution videos only make up a very small percentage of the organizations total media output. These videos are the most attention catching product of ISIS communication output and are directed at different audiences. One audience is the enemy, with the intention and striking fear and weakening their will to fight. Another audience are possible recruits (fighters and sympathisers) by demonstrating ISIS as dispensing ‘justice’ against perceived political, economic, social and other forms of injustices. Other genres include: immigrant testimonials (those who have moved to the Islamic State’s territory); economic news (depicting economic life and progress); battle footage (scenes of fighting and their military power and prowess); tributes to the State (endorsements and testimonials by people concerning living under the rule of ISIS); mergers and acquisitions (other terrorist organizations pledging their allegiance to ISIS) (Koerner Citation2016). This fits with Stanyer and Wring’s (Citation2004: 2) observation of the relevance and importance of creating a contextual relationship when addressing the prevailing power struggle, although this article concerns an organization as opposed to an individual political actor.

The 15 issues of Dabiq shall now be broken down in to the articles of these issues conforming to the six different categorizations observed by Koerner in the above paragraph. These categories are: (1) execution material; (2) immigrant testimonials and expectations of ‘citizens’; (3) economic news; (4) battle and enemy coverage; (5) tributes to the Islamic State; and (6) allies and mergers. After the materials of all of the articles of the 15 issues have been assigned to these categories, some examples of each category shall be evaluated in terms of the branding and political marketing approach taken.

The issues of Dabiq are formatted and organized in a standard manner. Above the table of contents of the issues is a quote from Abu Musab az-Zarqawi—“the spark has been lit here in Iraq, and its heat will continue to intensify—by Allah’s permission—until it burns the crusader armies in Dabiq.” This very short bit of text is highly symbolic and politically/culturally charged. The quote is from the founder of Islamic State, using rhetoric that gives religious “legitimacy,” a prophecy or forecast, and a sense of inevitability or destiny. Every issue of the magazine begins with a foreword, which is intended to set the tone and agenda of that particular issue. There were a total of 159 different forewords, articles, features, and so forth across the 15 issues. Forewords were excluded from the count as they did not fit in to any one of the above mentioned categories.

The results are given in further below, which visibly shows the divide among the different topics engaged in. Economic news and execution related materials were the least covered aspects in the copies of Dabiq. The economic news centered on the positive and innovative aspects of economic life under the Islamic State, such as the bringing back of the golden Dinar. Execution stories were written in the style of justification for the act, that is, explaining and trying to legitimatize the “good” side committing a bad action (issue 12 on Just Terror is a good example). This seemed to be an effort to shore up the connection and lessons of the communicated words and actions. The category of allies and mergers formed the third least covered topic, which revolved around different allies of ISIS and terrorist organizations that had joined into the ISIS brand. This gives an impression of an expanding brand that is attracting other external groups and therefore accentuating the “attractive” nature of the political/religious movement that ISIS tries to present. The projection of ISIS as an attractive political and religious movement and authority is found in the material concerning tributes to and about the organization. The two most commonly occurring themes in Dabiq were the coverage of ISIS in battle and the portrayal of its named enemies. Immigrant testimonials and the expectations that ISIS has of its new “citizens” was the largest category numerically that appeared (see issue 6, for example). It concerned the act of demonstrating how individuals could find a place and a meaning in life, and the expected behavior and values of those new “citizens.”

There is a distinct change in the nature and tone of the issues of Dabiq, the turning point is after Issue 11 (please refer to ), where the content and rhetoric concerned the use of symbolic culture and history as a means of political legitimacy and social capital that was directed at the building and expansion of the Islamic State in its transformation from a “normal” terrorist organization into a more state-like entity. From Issue 12, when the fortunes of war turn and ISIS begins losing territory and battles, the tone and the rhetoric are aimed at stiffening resistance, justifying extraordinary means (such as the “legitimacy” of terrorism in issue 12) and desperate symbolic promises of an ultimate victory (issue 15, the final, and the breaking of the cross theme).

In terms of a qualitative evaluation of the material in Dabiq, it is projected in terms of sets of diametrically opposed realities. The black and white world is depicted as being a defensive war by ISIS to protect “worthy” Muslims (issue 3). Thus they are ‘forced’ to fight (issue 4), but it is done in the name of righteousness and justice against a merciless and corrupt (including in the moral and spiritual sense of the meaning – issue 7). The texts have a lot of religious references as a means to try and legitimize the ideology and the actions of the organization (issues 8, 9, and 10). There are the use of symbolic historical and cultural references intended to both prophesize the future using the past and to legitimize the aims and mission of ISIS (issues 1, 2, 3, and 4). The religiously symbolically laden text is supported by numerous color photographs that add a further sense of reality to the subject at hand.

There is a lot of use of key speakers/influencers within the category of “immigrant testimonials and expectations,” which gives a specific face and character to the advice that is being offered to the reader. However, it can act as a form of ethos in order to persuade the reader of the veracity of what is written. However, it can also be used as a means to inspire the reader through creating a sense of empathy to become a part of the community in order to build, manage, or defend the utopian vision that has been presented to them. This is intended to be the basis of establishing, maintaining and enhancing the reciprocal political relationship between messenger and audience. As Newman (Citation1999: 46) observed, success in politics is measured in the ability of a political actor to move public opinion in the direction that they desire, terrorist organizations are not different in this regard. Whether this is to create a relationship of fear and avoidance with their enemies or to create a relationship of attraction through a sense of belonging and purpose among their supporters and recruits. Emotions and intangible aspects are an important part of both sets of positive and negative relationships.

The nature of the messages definitely follow Holbrook’s (Citation2014: 141) three central messages of terrorist messaging—communicating acts of terrorism, communicating ideological foundations, and engaging in counter-narrative messages. This is done through their creation of a strong brand recognition and identity among friend and foe alike, which had enabled them to rapidly differentiate themselves from other terrorist organizations. According to Nielsen (Citation2016: 71) this recognition and recall of the ISIS brand by the public is a mark of success in the quest for identification and differentiation from among the marketplace of competing brands. The resulting associations of notoriety with ISIS has resulted in a mass media “obsession” with the group that saw the relaying of unsubstantiated claims by the group for different attacks, which has an amplifying effect through publicity that exposes a much wider audience.

From issue 11 of Dabiq (September 2015), a gradual change in the focus and emphasis is observable in terms of the message focus and content. Instead of the narrative of victory and expansion that was projected in the previous issues, a new narrative of “resolve” (against enemy forces closing in), “resistance” (to protect the Islamic State, its citizens and family members against those enemy forces) and about supporters recognizing the true and “legitimate authority” (as opposed to imposters seeking to displace ISIS). There is a clear “defensive” tone in the content that seeks to inspire and to implore people to increase their energy and will to keep the utopian dream of the Islamic State alive at a time when it was being militarily routed on the battlefield. Thus, the messages moved from stories that supported the territorial expansion to ones that stressed extraordinary means and resolve to retain the Caliphate. Less attention is given to stories to encourage immigration, but to focus on the fighting spirit and the ethical/moral dimensions of the physical battle. Originally, the information program of ISIS was intended to support the organizational objectives of the physical realization of the Caliphate, to attract supporters, sympathizers, and “citizens” and to demoralize the enemy’s will and resolve to fight. The information program is now supporting the organizational objective of the survival of the physical Caliphate.

There are different emotions that are sought to elicit, which range anywhere from a sense of pride to a sense of outrage. This follows the observations by Sobieraj and Berry (Citation2011: 20) of the use of over-generalizations, sensationalism, misleading, or inaccurate information in order to side step “the messy nuances of complex political issues” in order to influence, mobilize, and direct their target audiences. Ultimately, Dabiq became a compromised part of the greater ISIS brand, not because it was out communicated in the information war that runs parallel to the physical war, but because events on the battlefield saw a highly politically symbolic and iconic tangible part of the political myth taken by military force from ISIS.

Future Research

This article takes the case of Dabiq and how it was used to create, maintain and expand the brand and marketing efforts of ISIS to increase their intangible strength, which was used as a means to try and compensate for their tangible weaknesses and military capacity/strength. Some apparent suggestive trends have been identified in the article, but this is a relatively small part of the much larger propaganda apparatus and only one terrorist organization has been subject to scrutiny. The research knowledge situation requires a more comprehensive study in order to test the reliability and validity of these tentative results. Below in graph one is the representation and summary of the findings of this article.

Conclusion

The communications of ISIS are about creating an emotionally based associative psychological resonance and a mutually reciprocal political relationship between the organization and its target publics. Propaganda is used to create and sustain the emotionally laden foundational myths of the organization. Branding is used to raise awareness and create automatic associations with ISIS by the targeted individuals and groups. Political marketing as a tool is used as a means of creating and sustaining reciprocal relationships between ISIS and enemies based upon fear and despair, and with recruits and allies based upon expectations of justice, belonging and/or a sense of meaning or purpose in life.

An organization such as ISIS is extremely protective of their reputation and image that is created through their brand communication. This is owed in no small part to the fact that they are tangibly (in terms of military capacity and power) weaker than their opponents on an open battlefield, intangibles are used to try and balance and offset those weaknesses. Military operations are subordinated to information operations, which creates an enhanced perception of risk and threat, which can be disproportionate to the actual tangibly achievable and operationally viable military capacity and power of ISIS. This has an effect upon the intangibles of ISIS—belief in the political and military leadership of the organization, the belief, and will to fight and attempt build their utopian version of a “pure” community.

The brand is essential for creating an organizational identity and to differentiate them from other terrorist organizations that are present in the marketplace of such organizations. Not only does this have intangible implications, such as being the most recognized terrorist organization through their organizational brands and symbols, but this builds on their reputation and resonance among different target audiences. This in turn has implications for funding and other material support as well as the number of recruits they are able to raise, the number of attacks they are able to inspire. This will also affect the quantity and quality of political exchanges and relationships it is able to create, maintain, and establish with different target groups.

Global mass media coverage of ISIS and especially its brand aspects brings about extra added value to that brand. It tends to reinforce and consolidate the publics’ opinion and perception of that brand, therefore they contribute to creating and maintaining a more resonate brand among a much wider and larger audience than may otherwise be possible. Hence, public opinion may identify ISIS as being one of the greatest perceived threats and risks globally, even if they are unable to physically support that reputation. However, as recent events on the battlefield have shown, the relationship of influence between the intangible and tangible is not a one-way effect, but they are interconnected and loses or setbacks in the intangible field can affect tangible operational aspects every much as tangible loses and setbacks can affect the intangible resonance and effectiveness of ISIS communications. There was a change in the quantity and quality of information that stressed the organizational objective of the physical survival of the Caliphate; earlier messages were geared towards the physical and intangible expansion of ISIS. The credibility and ability of ISIS to retain its brand and reputation that was achieved in the rapid succession of military victories and saturation coverage in the mass media was rooted and tied to its ability to continue its tangible domination that affected its intangible resonance with different publics. This is a highly difficult task to achieve for any physical political entity.

Notes

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Greg Simons

Greg Simons, Associate Professor, is a researcher at the Institute for Russian and Eurasian Studies at Uppsala University in Sweden and a lecturer at the Department of Communication Sciences at Turiba University in Latvia. He specialises in political comunication, especially the linkages between politics and information within the context of armed conflict.

Notes

1 The sources of risk offered were ISIS; climate change; cyber-attacks from other countries; the condition of the global economy; large numbers of refugees; US power and influence; Russian power and influence; and Chinese power and influence.

2 Please see https://clarionproject.org/islamic-state-isis-isil-propaganda-magazine-dabiq-50/ in order to access the different issues of the magazine.

3 It should be noted that ISIS are far from being unique in the use of uniforms and balaclavas, for example Germany’s Red Army Faction, the Irish Republican Army and others also made use of such clothing during public appearances or at certain rituals (such as funerals).c

References

- Altheide, D. L. 2006. “Terrorism and the Politics of Fear.” Cultural Studies Critical Methodologies 6 (4):415–439. doi:10.1177/1532708605285733

- Beifuss, A., and F. T. Bellini. 2013. Branding Terror: The Logotypes and Iconography of Insurgency Groups and Terrorist Organisations. London: Merrell Publishers.

- Bellanger-McMurdo, A. 2015. “A Fight for Statehood? ISIS and its Quest for Political Domination, E-International Relations.” Accessed October 26, 2017. http://www.e-ir.info/2015/10/05/a-fight-for-statehood-isis-and-its-quest-for-political-domination.

- Bergström, G., and K. Boréus. 2017. Analysing Text and Discourse: Eight Approaches for the Social Sciences. London: Sage.

- Carafano, J. 2016. “What Makes ISIS a Global Threat, Forbes.” Accessed October 18, 2017. https://www.forbes.com/sites/jamescarafano/2016/03/16/what-makes-isis-a-global-threat/#703059283629.

- Carter, C. J., H. Alkhshali, and S. Capelouto. 2014. “Kerry Assures Iraqis of US Support if they Unite Against Militias, CNN.” Accessed October 26, 2017. http://edition.cnn.com/2014/06/23/world/meast/iraq-crisis.

- Castells, M. 2007. “Communication, Power and Counter-Power in the Network Society.” International Journal of Communication 1, 238–266. 1932-8036/20070238.

- Clarke, C. P. 2017. “Is ISIS Breaking Apart? RAND.” Accessed October 18, 2017. https://www.rand.org/blog/2017/01/is-isis-breaking-apart.html.

- Clarke, C. P., and S. Metz. 2016. “ISIS Vs, Al Qaida: Battle of the Terrorist Brands, The National Interest.” Accessed October 18, 2017. http://nationalinterest.org/blog/the-buzz/isis-vs-al-qaida-battle-the-terrorist-brands-17370.

- Coker, M., E. Schmitt, and R. Callimachi. 2017. “With the Loss of its Caliphate, ISIS May Return to Guerrilla Roots, The New York Times.” Accessed October 19, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/18/world/middleeast/islamic-state-territory-attacks.html?emc=edit_th_20171019&nl=todaysheadlines&nlid=49872781&_r=0.

- Collard, R. 2015. “What we Have Learned Since ISIS Declared a Caliphate One Year Ago, Time.” Accessed October 26, 2017. http://time.com/3933568/isis-caliphate-one-year/.

- Conserva, H. T. 2003. Propaganda techniques. Bloomington (Indiana): 1st Books Library.

- Crooke, A. 2014. “You Can’t Understand ISIS If You Don’t Know the History of Wahhabism in Saudi Arabia, Huffington Post.” Accessed October 26, 2017. https://www.huffingtonpost.com/alastair-crooke/isis-wahhabism-saudi-arabia_b_5717157.html.

- Cwalina, W., A. Falkowski, and B. I. Newman. 2011. Political Marketing: Theoretical and Strategic Foundations. New York: M. E. Sharpe.

- Dingley, J. 2010. Terrorism and the politics of social change: A Durkheimian analysis. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Fan, Y. 2006. “Branding a Nation: What is Being Branded?” Journal of Vacation Marketing, 12 (1): 5–14. doi:10.1177/1356766706056633.

- Farwell, J. P. 2012. Persuasion and Power: The Art of Strategic Communication. Washington DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Franklin, B., M. Hogan, Q. Langley, N. Mosdell, and E. Pill. 2009. Key Concepts in Public Relations. London: Sage.

- Grinnell, D., S. MacDonald, and D. Mair. 2017. The Response of, and on, Twitter to the Release of Dabiq Issue 15. The Hague: Europol.

- Heath, R. L., and D. Waymer. 2014. “Terrorism: Social Capital, Social Construction, and Constructive Reality”. Public Relations Inquiry 3 (2), 227–244. doi:10.1177/2046147X14529683.

- Heck, A. 2017. “Images, Visions and Narrative Identity Formation of ISIS.” Global Discourse 7 (2–3): 244–259. doi:10.1080/23269995.2017.1342490.

- Holbrook, D. 2014. “Approaching Terrorist Public Relations Initiatives.” Public Relations Inquiry 3 (2), 141–161. doi:10.1177/2046147X14536179.

- 2015. “Islamic State Magazine Dabiq Withdrawn From Sale by Amazon, BBC News.”. Accessed October 23, 2017. http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-33035453.

- Jayyusi, L. 2012. “Terror, War and Disjunctures in the Global Order.” In Media and Terrorism: Global Perspectives, edited by D. Freedman and D. K. Thussu, 23–46. London: Sage.

- Johansen, H. P. M. 2012. Relational Political Marketing in Party-Centred Democracies: Because we Deserve it. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Juergensmeyer, M. 2017. “ISIS Inspired – or Branded? The World Huffington Post.” Accessed October 18, 2017. https://www.huffingtonpost.com/mark-juergensmeyer/isis-inspiredor-branded_b_10515398.html.

- Kean, T. H., and L. H. Hamilton. 2018. Digital Counterterrorism: Fighting Jihadists Online. Washington DC: Bipartisan Policy Centre.

- Khalaf, R. 2016. “The Deadly Draw of the ISIS Brand Without Borders, Financial Times.” Accessed October 18, 2017. https://www.ft.com/content/eab2a104-3243-11e6-bda0-04585c31b153?mhq5j=e7.

- Kirkpatrick, D. D. 2014. “ISIS’ Harsh Brand of Islam is Rooted in Austere Saudi Creed, The New York Times.” Accessed October 18, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/25/world/middleeast/isis-abu-bakr-baghdadi-caliph-wahhabi.html?_r=0.

- Koerner, B. I. 2016. “Why ISIS is Winning the Social Media War, Wired.” Accessed October 18, 2017. https://www.wired.com/2016/03/isis-winning-social-media-war-heres-beat/.

- Kydd, A. H. and B. F. Walter. 2006. “The Strategies of Terrorism.” International Security 31 (1), 49–80. doi:10.1162/isec.2006.31.1.49.

- Leaders in Nation Branding. 2017. “World PR.” Accessed on 21 June 2017. http://www.worldpr.org/nationbranding.php.

- Leavy, P. 2007. Iconic Events: Media, Politics, and Power in Retelling History. Lanham (MD): Lexington.

- Lees-Marshment, J. 2009. Political Marketing: Principles and Applications. London: Routledge.

- Marshall, H. 2002. “What do we do When we Code Data?” Qualitative Research Journal 2 (2), 56–70.

- Matusitz, J. 2013. Terrorism and Communication: A Critical Introduction. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage.

- Matusitz, J. 2015. Symbolism in Terrorism: Motivation, Communication and Behaviour. Lanham (MD): Rowman and Littlefield.

- McIntyre, J. 2016. “ISIS Fighters Have Been Run Out of Dabiq Forcing Them to Rename Their Magazine, Washington Examiner.” Accessed October 23, 2017. http://www.washingtonexaminer.com/isis-fighters-have-been-run-out-of-dabiq-forcing-them-to-rename-their-magazine/article/2604774.

- Melki, J., and M. Jabado. 2016. Mediated Public Diplomacy of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria: The Synergistic Use of Terrorism, Social Media and Branding. Media and Communication 4 (2), 92–103. doi:10.17645/mac.v4i2.432.

- Moeller, S. D. 2009. Packaging Terrorism: Co-opting News for Politics and Profit. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Mojon, J. M. 2017. “Baghdadi ‘The Ghost’: World Jihad’s Low Profile Boss, Yahoo News.” Accessed October 26, 2017. https://nz.news.yahoo.com/baghdadi-apos-ghost-apos-world-094029691.html.

- Moutot, M. 2016. “The ISIS ‘Brand’ is Spreading Worldwide, Experts Say, Al Arabiya.” Accessed October 18, 2017. https://english.alarabiya.net/en/perspective/features/2016/01/18/The-ISIS-brand-is-spreading-worldwide-say-experts.html.

- Mustafa, N. 2015. “Brand ISIS, The Walrus.” Accessed October 18, 2017. https://thewalrus.ca/brand-isis/.

- Nacos, B. L. 2007. Mass-Mediated Terrorism: The Central Role of the Media in Terrorism and Counter-Terrorism. Lanham (MD): Rowman and Littlefield.

- Newman, B. I. 2016. The Marketing Revolution in Politics: What Recent U.S. Presidential Campaigns can Teach us About Effective Marketing. Buffalo: University of Toronto Press.

- Newman, B. I. 1999. The Mass Marketing of Politics: Democracy in an Age of Manufactured Images. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage.

- Nielsen, S. W. 2016. “Measuring Political Brands: An Art and a Science of Mapping the Mind.” Journal of Political Marketing 15 (1), 70–95. doi:10.1080/15377857.2014.959682.

- Olidort, J. 2016. “Brand Control is More Important to ISIS Than Territory, The NYT in The Washington Institute for Near East Policy.” Accessed October 18, 2017. http://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/brand-control-is-more-important-to-isis-than-territory.

- Ormrod, R. P., S. C. M. Henneberg, and N. J. O’Shaughnessy. 2013. Political Marketing: Theory and Concepts. London: Sage.

- Patrick, B. A. 2012. The Ten Commandments of Propaganda. London: Arktos.

- Petroff, A. 2015. “ISIS: The Most Successful Terrorist Brand Ever? CNN.” Accessed October 18, 2017. http://money.cnn.com/2015/05/07/media/isis-brand-media-twitter/index.html.

- Poushter, J., and D. Manevich. 2017. “Globally, People Point to ISIS and Climate Change as Leading Security Threats, PEW Centre.” Accessed November 30, 2017. http://www.pewglobal.org/2017/08/01/globally-people-point-to-isis-and-climate-change-as-leading-security-threats/.

- Pratkanis, A., and E. Aronson. 2001. Age of Propaganda: The Every Day Use and Abuse of Persuasion. Revised Edition. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company.

- Qureshi, M. W. 2015. “Questioning the ‘ISIS Brand’ of Islam, Patheos.” Accessed October 18, 2017. http://www.patheos.com/blogs/altmuslim/2015/04/questioning-the-isis-brand-of-islam/.

- Robins-Early, N. 2016. “4 Things to Know About Dabiq, ISIS’ Slick Propaganda Magazine, Huffington Post.” Accessed October 23, 2017. https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/isis-dabiq-magazine_us_56a7e6cfe4b04936c0e8938a.

- Rosenfeld, S. 2015. “6 Keys to Understanding ISIS’ Barbaric Brand of Nihilism, Alternet.” Accessed October 18, 2017. https://www.alternet.org/election-2016/6-keys-understanding-isis-barbarism-apocalyptic-vision-and-desire-end-times-battle.

- Savigny, H. 2008. The Problem of Political Marketing. London: Continuum.

- Scammell, M. 2014. Consumer Democracy: The Marketing of Politics. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Schwarzmantel, J. 2008. Ideology and Politics. London: Sage.

- Shabo, M. E. 2008. Techniques of Propaganda and Persuasion. Clayton (DE): Prestwick House.

- Sheffield, H. 2015. “ISIS has Built a Global Brand Using Nutella, Celebrity and Social Media, The Independent.” Accessed October 18, 2017. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/business/news/isis-has-built-a-global-brand-using-nutella-celebrity-and-social-media-10095915.html.

- Simons, G. 2016. “Islamic Extremism and the War for Hearts and Minds.” Global Affairs 2 (1), 91–99.

- Simons, G. 2017. “Analysing Terrorist Use of Public Relations: ISIS and Al Qaeda.” In Experiencing Public Relations: International Voices, edited by E. Bridgen and D. Verčič, 194–208. London: Routledge.

- Simons, G. 2016. “Fatal Attraction: The Lure of the Islamic State, Sustainable Security.” Accessed October 23, 2017. https://sustainablesecurity.org/2016/09/16/fatal-attraction-the-lure-of-islamic-state/.

- Simons, G., and A. Sillanpaa, eds. 2016. The Kremlin and DAESH Information Activities. Riga: NATO Stratcom COE.

- Sobieraj, S., and J. M. Berry. 2011. “From Incivility to Outrage: Political Discourse in Blogs, Talk Radio, and Cable News.” Political Communication 28 (1), 19–41. doi:10.1080/10584609.2010.542360.

- Spencer, A. 2017. “Images Visions, and Narrative Identity Formation of ISIS: A Reply.” Global Discourse 7 (2–3), 260–263. doi:10.1080/23269995.2017.1347853.

- Spiller, R., C. Breidenich, and U. Hilgers-Yilmaz. 2016. “Visual Rhetoric of the Islamic State (IS): Persuasion in the Field of Terror.” In Making Trans/National Contemporary Design History, edited by W. Wong, Y. Siuyi, and T. Lin, 206–213. Sao Paulo: Blucher.

- Staff Writers. 2017. “A Catalogue of IS Massacres, AFP in Space War.” Accessed October 24, 2017. http://www.spacewar.com/reports/A_catalogue_of_IS_massacres_999.html.

- Stanyer, J., and D. Wring. 2004. “Public Images, Private Lives: An Introduction.” Parliamentary Affairs 57 (1), 1–8. doi:10.1093/pa/gsh001.

- Taylor, P. M. 2003. Munitions of the Mind: A History of Propaganda From the Ancient World to the Present Day, 3rd ed. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Thorne, K. 2005. “Designing Virtual Organisations? Themes and Trends in Political and Organisational Discourses.” Journal of Management Development 24 (7), 580–607. doi:10.1108/02621710510608731.

- Tuman, J. S. 2010. Communicating Terror: The Rhetorical Dimensions of Terrorism. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage.

- Windrem, R. 2014. “Will ISIS Eclipse Al Qaeda as No. 1 Global Terrorism ‘Brand’? NBC News.” Accessed October 18, 2017. https://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/iraq-turmoil/will-isis-eclipse-al-qaeda-no-1-global-terrorism-brand-n140131.

- Withnall, A. 2015. “Isis to Launch First 24-hour Online TV Channel Featuring British Hostage John Cantlie and Flagship Show 'Time to Recruit', The Independent.” Accessed October 27, 2017. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/isis-to-launch-first-24-hour-online-tv-channel-featuring-british-hostage-john-cantlie-and-flagship-9986254.html.)

- Wood, G. 2015. “What ISIS Really Wants, The Atlantic.” Accessed October 18, 2017. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2015/03/what-isis-really-wants/384980/.

- World PR. 2018. WorldPR Global Leadership Ranking 2018: A Modern Nation Branding Tool. London: WorldPR.

- Zaharna, R. S. 2016. “Reassessing ‘Whose Story Wins’: The Trajectory of Identity Resilience in Narrative Contests.” International Journal of Communication 10, 4407–4438.