ABSTRACT

This study explores how hospitality businesses source low pesticide risk fresh produce from smallholder farmers. Stakeholder interviews across Europe, Africa, and Southeast Asia (n=19) reveal a lack of standardisation for low-pesticide fresh produce. Despite concerns about potential pesticide contamination, local, seasonal and low-carbon options are prioritized, and intermediaries are considered as providers of food safety reassurance. Collaboration with smallholder farmers is limited due to unpredictable supply and capacity. The study calls for the set-up of industry standards on low pesticide risk fresh produce and smallholder collaboration capacity building, potentially through technology, to improve food safety, sustainability, and supply chain resilience.

Introduction

Food safety represents a critical issue in hospitality and food service (HaFS) given that safe food provisioning is paramount for business longevity and management of reputational risks (Knowles, Citation2012). The importance of food safety has been recognized by the United Nations, who call for its effective management in all stages of the global food supply chain, including the HaFS sector (FAO, Citation2024). Seventy-five percent of UK customers claim they would never return to a HaFS enterprise serving unsafe food, thus showcasing how food safety determines consumer loyalty (Eversham, Citation2021). As the cases of unsafe food provisioning in the HaFS sector receive significant public attention, it may negatively influence prospective demand (Seo et al., Citation2018). This highlights the need for HaFS organizations to prioritize food safety in their business strategies and operations.

Food safety is defined as “the biological, chemical, or physical status of a food that will permit its consumption without incurring excessive risk of injury, morbidity, or mortality” (Keener, Citation2010). In HaFS enterprises, food safety is linked to quality management as quality assurance is necessitated to provide safe food (Arendt et al., Citation2013). This requires HaFS enterprises to embed food safety management systems (FSMSs) in their strategies and operations as only a robust, systematic approach to food handling, preparation, and service can guarantee safe food provisioning (Al Yousuf et al., Citation2015).

FSMSs are a set of procedures determining actions taken by the food business operator to ensure their food is safe to consume, of the required quality, and legally compliant (Swainson, Citation2018). FSMSs underscore the interplay between food safety management and food quality management, which makes it relevant for HaFS enterprises with their highly competitive customer market (Manning, Citation2018a). In this market, safe food provisioning concurs with quality food provisioning as consumers need the reassurance that the food served meets the industry and legal standards on safety and quality (Cha & Borchgrevink, Citation2019). Examples of such reassurance are set by international standards such as the ISO 9001 Quality Management System (ISO Citation9001, 2015). Business commitment to provide safe, quality food is also exemplified by the Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP) procedures (Food Standards Agency, Citation2017). Lastly, the ISO 22000 standard combines the principles of HACCP and ISO 9001, thus offering a synergistic approach to food safety (Panghal et al., Citation2018).

Implementing FSMSs in HaFS enterprises is challenging because the sector is represented by commercial and non-for-profit organizations, independent small-to-medium sized enterprises (SMEs) and large multinational chains (Al Kaabi et al., Citation2015). Given sectoral diversity, significant variations in organizational culture, management style, and the level of food safety knowledge and skills hamper the effectiveness of FSMSs within HaFS organizations, thus providing no “one size fits all” approach (Manning, Citation2018b). Empirical research is therefore necessitated to examine how food safety is implemented in different segments of the HaFS sector and in the enterprises of various size and specialism (Luning et al., Citation2013) to establish the determinants of effective implementation and identify “best practices” (Maiberger & Sunmola, Citation2023). Research should focus on SMEs as this category of HaFS enterprises do not have the necessary (human, financial, and technological) resources to embrace FSMSs which can lead to their market disadvantage (Al Khaja et al., Citation2015).

Although food safety is critical for HaFS enterprises, the related research agenda is limited. The recent systematic literature review on the determinants of FSMSs in global food supply chains by Nguyen and Li (Citation2022) has identified no empirical investigations of HaFS organizations. Another review by Maiberger and Sunmola (Citation2023) has revealed 12 studies concerned with HaFS enterprises. These studies focus on HaFS managers, considering the role of organizational culture (Wiśniewska et al., Citation2019) and organizational food safety climate (Clark et al., Citation2019) in the design and implementation of FSMSs. Studies have also examined HaFS staff knowledge and skills of food safety processes and procedures (De Andrade et al., Citation2021) outlining the needs for employees’ upskilling and training (Seaman & Eves, Citation2010).

These two reviews have highlighted the need for more research on food safety standards and procedures among organizations supplying food to HaFS enterprises, such as food producers/growers. The focus on food producers/growers is warranted because they represent a critical stakeholder for HaFS enterprises (Vasilakakis & Sdrali, Citation2023) given that food safety starts on the farm (PEW Charitable Trusts, Citation2017). This is aligned with the “farmer first” paradigm which advocates that food producers/growers should be prioritized in interventions concerned with the provision of healthy, safe, and sustainable food (Rezaei, Citation2018). This priority is justified as farmers, located in the initial stage of the food supply chain, determine quality, safety, and sustainability of food in all subsequent stages (Filimonau & Ermolaev, Citation2021). A more holistic, integrated approach to examining food safety in the HaFS sector is also called for by Julien-Javaux et al. (Citation2019) who posit that food safety strategies should be designed and implemented from the “farm to fork” perspective. This is to ensure that FSMSs remain robust and comprehensive in all stages of the food supply chain, given that these are interlinked and interdependent (Kirezieva et al., Citation2013). More research on food safety standards and procedures in HaFS organizations and their suppliers is therefore warranted as it can provide important insights into the determinants of (un)safe food provision and highlight opportunities for policy and management interventions to ensure food safety in the HaFS sector (Rebouçrebouças et al., Citation2017).

This study explores the opportunities and challenges of the provision of safe farm produce to HaFS organizations. More specifically, it examines how/if low pesticide risk fresh fruits and vegetables can be provided to HaFS organizations by smallholder farmers. The focus on low pesticide risk produce is deliberate because pesticides represent the leading causes of mortality and morbidity from food consumption (WHO, Citation2022). The focus on smallholder farmers is because they have fewer opportunities to engage with FSMSs (Phiri et al., Citation2019) and supply fresh produce directly to HaFS enterprises as the global food supply is dominated by large multinational corporations (ETC Group, Citation2022). The geographical scope of the study is Africa and South-East Asia because these regions represent large source markets of fresh fruits and vegetables for HaFS organizations located in Europe. Lastly, the sectoral focus on fresh fruits and vegetables is because (1) these are often sourced from the above-referenced regions while being (2) subjected to excessive use of pesticides (Van Boxstael et al., Citation2013). The next section presents further background to this study.

Literature review

Food supply chain management in HaFS organizations

Food supply chain management plays a critical role in HaFS strategies and operations by ensuring the efficient and effective distribution of food from the point of its production/growing to the point of consumption (Ku et al., Citation2020). HaFS enterprises should strive for transparent and lean food supply chains as these advocate a systematic approach to the design of streamlined and reliable supply operations (Al-Aomar & Hussain, Citation2018). Lean food supply chains support elimination of waste which can be physical, such as lost and wasted food, as well as nonphysical, such as the time wasted or the economic value lost in the result of operational inefficiencies (Gładysz et al., Citation2020). Lean food supply chain management is directly related to the challenge of food safety as unsafe food delivered to the consumer implies strategic and operational inefficiency which, if undetected, can have major detrimental implications, including business extinction (Vlachos, Citation2015).

It is important to note however that, when striving for more lean food supply chains, there is a risk of marginalizing smallholder farmers in favor of suppliers who can provide the economies of scale demanded by large HaFS enterprises or intermediaries. The limited resources of smallholders restrict their ability to embrace the lean principles which disadvantages them in favor of large, multinational corporations (Perdana & Citation2012). Research on how to integrate the lean principles in smallholder farming more effectively is needed, especially from the perspective of safe food provisioning (Roop et al., Citation2022). This is because lean food supply chains present an example of a management system where food safety is critical and poses operational challenges that need resolving based on the contextual limitations of small-scale food production/growing, such as restricted knowledge, skills, and finance (Aworh, Citation2021).

Actors of the HaFS food supply chain

Multiple actors are engaged in the HaFS food supply chain (Baert et al., Citation2012). They are represented by food producers/growers, such as (smallholder) farmers, any intermediaries involved in the delivery/distribution of food from farms to HaFS enterprises, such as catering supply companies or fresh food markets, and the HaFS organizations themselves. The actors also incorporate any regulatory and/or monitoring bodies determining how the HaFS sector operates, such as local, regional, and national governments, but also various non-governmental organizations, industry associations, and trade unions. The relationships between these actors are complex and require careful examination, especially from the perspective of safe food provisioning (Van Boxstael et al., Citation2013).

Research on the relationships between such stakeholders as HaFS organizations and smallholder farmers from the perspective of safe food provisioning is limited. Studies have considered how smallholder farmers can be integrated into agrotourism (Khanal & Mishra, Citation2014) and agri-food tourism networks (Liu et al., Citation2017). Studies have also examined tourism as a vehicle of regional and rural (re-)development (Hjalager & Johansen, Citation2013; Knowd, Citation2006), especially from the perspective of smallholder farmers whose engagement with tourist activities, such as during food festivals, can aid in revitalization (Sanches-Pereira et al., Citation2017). Although this research line offers valuable insights into the drivers of tourist engagement with fresh farm produce (Garner & Ayala, Citation2019), it does not examine the determinants of food supply by smallholder farmers to HaFS organizations. Further, this research is not concerned with the issue of food safety in the HaFS food supply chains as the food served on an agrotourism farm or at a food festival is considered safe by default (Garner & Ayala, Citation2019).

A related line of research has been concerned with the phenomenon of local food, i.e., food produced/grown by local farmers, in the HaFS context (Roy et al., Citation2017). Studies have considered the determinants of embracing local food by HaFS providers (Duarte Alonso & O’Neill, Citation2010) and customers (Filimonau & Krivcova, Citation2017). Safety has been indirectly mentioned in such studies because knowledge on the food origin is often associated with its safety (Roy, Citation2022).

Very little research has considered the issue of pesticide contamination in the food served in HaFS organizations. Ridderstaat and Okumus (Citation2019) examine the standards and procedures of sanitation inspection in restaurants where pesticides are featured as one of the inspected categories. They do not however investigate the source of pesticide contamination, thus excluding food supply chain management from analysis. Lee and Liu (Citation2020) report the results of health safety inspection in public foodservice operations with pesticide contamination being one of the items scrutinized. However, similar to Ridderstaat and Okumus (Citation2019), this study does not examine where the food contaminated with pesticides comes from and how it is procured. To our knowledge, there is no further research dealing with low pesticide risk farm produce in the HaFS sector, let alone its provisioning by smallholder farmers. The lack of studies on the relationships between HaFS organizations and smallholders, especially from the perspective of the provision of safe farm produce, such as low pesticide risk fruits and vegetables, calls for more nuanced, empirical investigations.

Inter-actor collaboration in HaFS food supply chains

Stakeholder theory can explain the relationships between different actors in HaFS food supply chains, including those between HaFS organizations and smallholder farmers (Govindan, Citation2018). This theory has been used extensively to examine how the inter-actor relationships emerge and evolve, including the perspective of trust building and potential (im)balance of power in global food supply chains (O’Donovan et al., Citation2012). Stakeholder theory can aid in understanding the issues of food safety by examining how and why HaFS enterprises (do not) collaborate with smallholder farmers for safe food provisioning (Minnens et al., Citation2019).

Stakeholder theory calls for inter-actor collaboration as it is considered key for effective management of HaFS food supply chains, especially from the standpoint of safety and sustainability (Bhattacharya & Fayezi, Citation2021). Collaboration enhances the social and network capital of HaFS enterprises and other actors of their food supply chain, thus improving resilience and business value ecosystems (Cho et al., Citation2017). Collaboration can also drive the design of food quality standards, including those related to safety, and ensure adherence to these standards by all actors of the food supply chain (Shin & Cho, Citation2022). The importance of inter-actor collaboration has been recognized at the highest levels of global decision-making: for example, it is featured in the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 17 “Partnerships for the goals” (United Nations, Citation2024). This goal calls for multiple actors representing various economic sectors and markets to work together to enable progress of the global food supply chains toward equality, safety, and sustainability (Djekic et al., Citation2021).

Collaboration is especially important in the context of direct, farm-to-fork supply chain relationships (Meneguel et al., Citation2022) as it enhances trust between food producers/growers and HaFS enterprises (O’Donovan et al., Citation2012). This holds implications for food safety as trust can prompt HaFS organizations to procure food directly from food producers/growers, including those of smaller scale (Dania et al., Citation2018). This has been evidenced in research concerned with halal food provisioning, for example (Ali et al., Citation2017).

The level of trust in HaFS food supply chains correlates with their size (Roy et al., Citation2017) i.e., short(er) food supply chains are more trustworthy (Roy & Ballantine, Citation2020). Short(er) food supply chains facilitate direct interactions between food producers/growers and HaFS enterprises (Renting et al., Citation2003), thus increasing chances for trust-building, especially in the context of food safety (DeLind & Howard, Citation2008). Few studies have however examined how/if HaFS enterprises work with food producers/growers directly to build trust and ensure safe food provisioning (Roy, Citation2022).

Alternative approaches to management of HaFS food supply chains

Inter-actor collaboration underpins novel/unconventional business models aiming to promote transparency, sustainability, and resilience, such as short food supply chains (SFSCs) and alternative food networks (AFNs) (Filimonau & Ermolaev, Citation2022). The European Commission defines SFSCs as the chains involving operators committed to collaboration, local economic development and close geographical and social relations between food producers and consumers (Kneafsey et al., Citation2013). SFSCs are beneficial for rural re-development as they allow for the integration of often disadvantaged actors of the food supply chain, such as smallholder farmers (Renting et al., Citation2003). SFSCs are also beneficial for safe food provisioning given that geographical proximity and inter-dependence can build trusting relationships between food producers/growers and consumers (Giampietri et al., Citation2016). All in all, SFSCs represent an interesting alternative to conventional food supply chains (Thomé et al., Citation2021). Research on SFSCs is particularly needed in developing economies where the number of smallholder farmers is high, but they do not have access to international food markets (Benedek et al., Citation2018). Research on developing economies is further necessitated because extant studies on SFSCs have focused on developed countries with their dramatically different political and socio-economic settings (Bui et al., Citation2021).

Likewise, AFNs are defined by such elements as local food production and consumption, but also involvement of SFSCs, thus integrating spatial and social proximity (Gori & Castellini, Citation2023). AFNs aim to build fairer, more sustainable relationships between food supply chain actors (Goodman et al., Citation2012). Thus, both SFSCs and AFNs promote inter-actor collaboration to build trust and improve value for food producers/growers and their customers, such as HaFS enterprises.

SFSCs and AFNs are not without limitations. Compared to conventional business models, they have been criticized for high(er) costs of implementation and more extensive labor requirements which may negatively influence performance of the stakeholders involved, especially farmers (Chiaverina et al., Citation2023). The critique has also pinpointed the origin of SFSCs and AFNs in western societies, thus making them more suitable and/or reflective of local economic realities (Chiaverina et al., Citation2024). The need to better understand the overall sustainability of SFSCs and AFNs has also been called for, especially from the perspective of multiple, negative and positive, effects, including those attributed to indirect impacts which can be delayed in time (Michel-Villarreal et al., Citation2019). Despite these limitations, the potential of SFSCs and AFNs for HaFS food supply chains has been recognized (Paciarotti et al., Citation2022), but empirical investigations on their role and the determinants of their adoption by HaFS stakeholders remain limited (Paciarotti & Torregiani, Citation2018), especially from the perspective of safe food provisioning.

Summary and the research gap

Although food safety represents a critical issue for HaFS organizations, the related research agenda is under-developed. Little is known about the extent to which food safety considerations, as part of organizational FSMSs, play a role in how HaFS enterprises choose their food suppliers. This especially concerns fresh farm produce, such as fruits and vegetables, which is prone to excessive use of pesticides.

Little is also known about how/if HaFS enterprises, especially in developing countries, collaborate with smallholder farmers for safe food provisioning, particularly relating to low pesticide risk. Such collaboration is necessary as it can aid in building the HaFS food supply chains that are more transparent, resilient, and sustainable in the longer term. The level of knowledge and the extent of engagement of HaFS organizations in such novel/unconventional models of food supply chains as SFSCs and AFNs are also unknown.

Using the stakeholder theory as a guide, this study will explore how/if HaFS organizations collaborate with smallholder farmers in Africa and South-East Asia for the provision of low pesticide risk fresh farm produce. The next section presents this study’s methodology.

Methodology

Limited research on the topic in question positioned this study as exploratory, and the methodology of qualitative research, i.e., in-depth, semi-structured stakeholder interviews, was therefore used for primary data collection and analysis. Qualitative research produces detailed accounts of people’s experiences and enables them to explain their true opinions through interactive discussions facilitated by the research team (Hennink et al., Citation2020). The design of qualitative research, such as interviews, is flexible and offers scope for clarifying and probing questions, thus facilitating the extraction of more detailed information and enabling its more accurate interpretation (Marshall & Rossman, Citation2014).

Nineteen semi-structured interviews were conducted with stakeholders who were purposefully selected because they represented what Suri (Citation2011) described as the “information-rich cases,” i.e., the individuals who possessed first-hand knowledge and profound experience of working on the topic under scrutiny. Purposeful sampling is justified when expert knowledge on a very particular topic is required (Moser & Korstjens, Citation2018), such as in the case of the current study. To this end, interviews were undertaken with: 1) senior managers of HaFS enterprises who have the experience of sourcing fresh fruits and vegetables from smallholder farmers (at the level of a Chief Executive Officer or an Executive Chef); 2) international tourism certification organizations whose certification criteria deal with sustainable food procurement; 3) representatives of the national HaFS industry associations specializing in procurement of safe and sustainable food; 4) representatives of the national farming associations knowledgeable about food safety in smallholder food production; 5) representatives of the national food safety/organic food certification bodies; and 6) senior academics majoring in food safety (at the level of a Full Professor with an established track record of publications on the topic under scrutiny). To be eligible for interviews, the non-academic stakeholders must have had at least 3 years of work experience in a senior position in their respective fields. The stakeholders were based in Europe (the UK), South East Asia (Malaysia and Indonesia), Eastern (Mauritius, Uganda, Kenya) and Southern (South Africa) Africa, .

Table 1. Study participants (n = 19).

The stakeholders were recruited using professional connections of the research team members who examined the issue in focus for a long time and developed a network of contacts which was used to reach for willing participants. The number of interviews was determined by thematic saturation. Depending on the complexity of a research topic, 5–40 interviews are necessary for saturation (Guest et al., Citation2020), and our study fits into this recommended range.

An interview guide was informed by the literature review. In particular, the findings of Al Kaabi et al. (Citation2015), Julien-Javaux et al. (Citation2019), Kirezieva et al. (Citation2013), Manning (Citation2018b), Manning (Citation2018a), Rezaei (Citation2018) and Roy (Citation2022) were used to devise a list of preliminary interview questions and identify initial interview themes. As recommended by Srivastava and Hopwood (Citation2009), the list was continuously updated after interviewing commenced following the critical reflection and iterative analysis of the findings. To ensure content and face validity, the interview guide was piloted with three individuals representing (1) a senior HaFS business professional responsible for food procurement; (2) a senior officer in the national farming association; (3) an academic majoring in sustainable food supply chain management. Supplementary material (Appendix 1) contains a copy of the main interview questions.

Interviews were conducted in October–December 2023. Given the international scope of the study, which rendered face-to-face interaction time-consuming and costly, interviewing was administered via Zoom and Microsoft Teams. Interviews were conducted in English and averaged 46 minutes in duration; they were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Participation was not incentivized.

Data were analyzed using the six-step iterative process of thematic analysis outlined by Clarke and Braun (Citation2017). To this end, familiarization with raw data was undertaken in Step 1 by means of carefully reading and re-reading interview transcripts. This enabled formation of initial codes in Step 2. These codes were refined and combined into themes in Step 3. The themes were reviewed and refined in Step 4 to ensure they accurately reflected upon and conveyed the true meanings of the codes. In Step 5 the themes were defined and named. The results of thematic analysis were written up in Step 6, and representative quotes were selected to more effectively transmit the key points emerging from interviews.

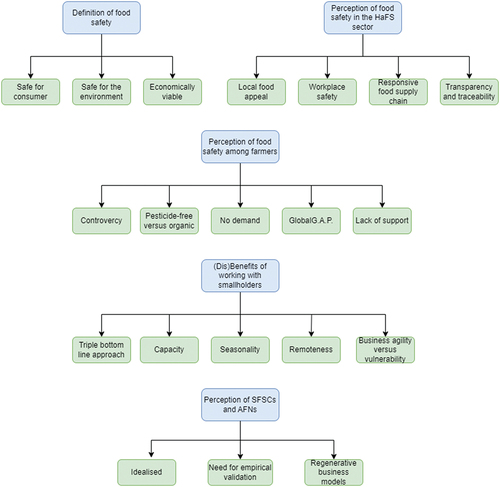

To ensure trustworthiness, as recommended by Nowell et al. (Citation2017), data were inter-coded by two members of the research team. NVivo 14 was used to facilitate coding and visualize relationships between the codes. The results of data coding were compared across the team, and any discrepancies found were discussed and corrected. The inter-coder reliability was above 90%, thus exceeding the recommended threshold of 80% (Campbell et al., Citation2013). outlines the final coding structure.

Findings

presents a summary of the key study’s findings which are explained in detail below.

Definition of fresh food safety in relation to pesticide use

The participants agreed that the issue of fresh food safety in relation to pesticide use was complex and its understanding revolved around the following three perspectives: fresh fruits and vegetables should be 1) safe to consume; 2) safe to produce/grow for the environment; 3) economically viable to produce/grow and consume from the financial perspective. The third perspective was considered most problematic as the following dilemma was mentioned here by one participant: “farmers could use no pesticides, but, in this case, the fresh produce would be too expensive [for HaFS organizations] to buy because of the limited amounts grown without the pesticides”. This was referred to as the basic law of economics i.e., low supply drove demand which, in turn, increased prices. Some HaFS segments, such as luxury hotels and fine dining restaurants, could afford fresh produce grown without pesticides, but the bulk of the sector could not. This especially applied to HaFS enterprises operating in developing countries. From the farmers’ perspective, growing fresh produce without pesticides was expensive because of the considerable effort required to preserve it from pests. The laborious nature of such growing practices was a major off-putting factor, especially for smallholders with their limited resources. The market of fruits and vegetables grown without pesticides was therefore considered niche.

Smallholders, like many larger farmers (often referred to in interviews as “commercial farmers”) had therefore no choice but to use pesticides. According to the participants, many actors of the food supply chain, such as HaFS organizations, academics, and authorities, often forget about the cost element of food production. They call for fruits and vegetables to be produced without pesticides, but they do not necessarily understand that such production cannot be cheap. There should be a balance between the use of pesticides and the cost of fresh produce. Stakeholders, especially HaFS organizations, should understand the challenge of balancing out the use of pesticides and the cost of food production/growing. The problem was not seen in the conceptualization of pesticide-free agriculture, but in its implementation. The participants considered the concept of pesticide-free agriculture idealized and not necessarily suitable for the modern world’s realities where increasing quantities of food would be required to meet the growing demand of the HaFS sector. As one participant put it: “it [pesticide-free growing] looks good on paper, but it barely works in reality”. The term “low pesticide risk fresh produce” was therefore preferred by the participants as it highlighted the use of pesticides albeit in safe quantities.

The participants considered the following types of fresh produce most vulnerable to excessive pesticide use and, therefore, being potentially unsafe: cabbage, cauliflower, broccoli, aubergine, chilies, tomato, potato, capsicum, salad, onion, leek, and garlic. Most fruits were mentioned as being at risk. The most popular fresh fruits and vegetables were seen as most problematic because they “had to be grown in large quantities to satisfy the market demand”. Not exported fruits and vegetables i.e., those used for local/domestic market, were also considered as susceptible to excessive pesticide use because these were not being scrutinized by big international brands for safety requirements. In other words, there was a clear discrepancy between fruits and vegetables served to the international (considered largely safe) versus domestic (considered to be of higher risk of being not safe enough or not passing a potential safety audit) market.

When discussing the role of food safety in HaFS strategies and operations, it was considered key for business survival. It was repeatedly emphasized that customers would not patronize a HaFS enterprise where food safety breaches occurred. Food safety was therefore perceived as linked to reputation. Once compromised, it was considered difficult, if not impossible, to restore. Food safety was also perceived as linked to quality given that “quality provision without safety provision [in HaFS operations] could not be achieved”. Safety was considered an integral element of quality management given its critical impact on customer return.

The participants recognized that safety of fresh produce would gain more prominence in the future political and management agendas because of the increasing intake of fruits and vegetables in contemporary diets, especially among Generation Y and Z consumers. HaFS customers were getting increasingly concerned with food safety because of the issue of trust (“once ruined, it cannot be restored”) and the influence of COVID-19 which raised public awareness of food safety when eating out. Lastly, growing populations in developing economies would fuel food consumption outside the home. This trend would require better scrutinizing the food served by HaFS organizations to ensure its safety, especially if/when a new food operator enters the market.

Perception of food safety among HaFS organizations

According to the participants, currently, there is no specific demand from HaFS organizations for low pesticide risk produce. Instead, there is a strong, growing demand for local food. This applies to HaFS organizations based in the established markets, such as the UK and South Africa, but, increasingly, those operating in developing countries, such as Kenya, Indonesia, and Malaysia. Although HaFS enterprises are willing to purchase local food, they do not yet pay attention to how this food is produced and if it is grown using (no or low quantities of) pesticides. HaFS enterprises assume that the local food they are buying is “safe by default”, as one participant put it. The factor of localism therefore outweighs the factor of perceived safety.

However, this perception may change as there is a growing interest among HaFS professionals in tracing the origin of the food they purchase. This is indirectly related to the issue of food safety as HaFS organizations want to know who grows their food and how they grow it. Therefore, transparency and traceability are getting increasingly important, and solutions will be required to ensure the provenance of food can be verified. The blockchain technology (BCT) and artificial intelligence (AI) can aid in tracing food origin and ensuring its safety. However, the scope of BCT and AI application is limited by the resource base of smallholder farmers and HaFS organizations, especially in developing economies. Larger, commercial farmers and multinational HaFS corporations are likely to adopt these technologies first, thus “disadvantaging smallholders and SMEs”. Further, the exact potential of BCT and AI for procurement of safe fresh produce in the HaFS sector requires an in-depth exploration documenting examples and case studies of their successful applications. This is to signal the relevance of these technological solutions to HaFS organizations, thus encouraging adoption.

Currently, the attributes of food quality (i.e., esthetics, taste, freshness) are more important for HaFS organizations than the safety attributes. Responsiveness of the food supply chain is another key factor prioritized over food safety. As one participant put it: “I need something now, it’s more important than safety as I assume food is safe by definition” highlighting that the speed of the supplier’s reaction to emerging demands is critical. Most HaFS organizations take food safety for granted and do not audit it. An analogy with halal food was given whereby the responsibility for halal food provisioning lied on the supply side (for instance, a butcher) rather than the demand side (for example, a HaFS enterprise).

Further, as most HaFS organizations rely on intermediaries to procure fresh produce, these offer an extra layer of reassurance that food is safe. In a way, using a middleman, HaFS enterprises shift responsibility for auditing food safety to another party, thus adopting the “out of sight, out of mind” approach. This reassurance can prevent HaFS organizations, especially SMEs, from sourcing fresh produce directly from smallholder farmers. However, this approach can backfire because intermediaries may, in turn, rely on other intermediaries, especially if fresh produce is procured by a Europe-based HaFS organization from an Asia-based farmer, thus making the food supply chain less transparent. This increases the opportunity for food fraud to occur, thus reinforcing the need to ensure transparency and traceability of global food supply chains, thereby emphasizing the potential of such solutions as BCT and AI.

In developed countries, such as the UK and South Africa, the industry focus is gradually shifting toward the high (carbon) emission food, such as meat and dairy. Fruits and vegetables can also fall under this category, for example, in the case of a mango sold in the UK but grown in Thailand. The focus on the high (carbon) emission food, in light of the growing global agenda to mitigate climate change, “diverts attention of [HaFS organizations] from the challenge of low pesticide risk fresh produce”, according to some participants.

Likewise, there is a growing interest among HaFS organizations in “seasonal fresh produce” which is perceived safe although it may not be the case in reality. The appeal of seasonal fresh produce is stronger than low pesticide risk fresh produce. This is, again, because the seasonal produce provided by intermediaries is considered safe. In fact, the interviews prompted some participants representing HaFS organizations to re-think safety of their food in terms of pesticide use as well as to scrutinize their food supply chains for safety, transparency, and traceability.

Many participants associated food safety with the “safety measures applied in the workplace,” such as health and hygiene practices in specific HaFS organizations. These workplace related safety practices remain important after COVID-19. For example, in Zambia, employees in some HaFS enterprises have to undergo multiple medical tests every 6 months to ensure there are no transmissible diseases. As for the aspects of food safety beyond workplace, the bulk of the HaFS sector do not pay attention to this issue yet.

When speaking about corporate FSMSs, the participants argued that most HaFS organizations did not have it in place. This particularly concerned SMEs which did not practise FSMSs due to limited resources. Some HaFS organizations had standard operating procedures (SOPs), but these were mostly discussed in the context of workplace food safety rather than procurement of fresh produce. Currently, in the HaFS sector, there are no established food safety standards on fresh produce, either related to the use of pesticides or in general. Travelife have developed some certification requirements regarding banned pesticides that are based on the Stockholm convention (Travelife, Citation2024). These requirements were not however known to the study’s participants, potentially highlighting the lack of marketing or the lack of interest. The lack of food safety standards on pesticide use, or limited stakeholder awareness of such standards, is partially because the HaFS sector is too diverse, and standardization can be problematic. For example, the standards developed for a restaurant may not be suitable for a cruise given their considerably different business models of food procurement. This is also because there are many farmers in the countries where fresh produce comes from who may not be apt for standardization.

The language was considered important when marketing low pesticide risk fresh produce to HaFS organizations. The participants preferred the claim “low pesticide risk” to the claim “organic”. This is because the former sends a powerful message about the food being safer, healthier, and making less pollution. Many participants were cynical about the term “organic” given its ambiguous meaning. Plus, organic certification was considered too expensive which immediately disadvantaged many farmers, especially smallholders, thus portraying organic produce as being inaccessible and unsustainable in the participants’ eyes. The fresh produce which has low pesticide risk does not require extra certification for now, but it highlights the issue of trust between farmers and HaFS organizations. If a farmer/grower claims that their food is low pesticide risk, HaFS organizations, especially SMEs, should trust this claim as they cannot audit its validity. Trusting relationships built between farmers and HaFS organizations are therefore important for the provision of low pesticide risk produce.

Lastly, the participants argued that the issue of pesticide use when growing fresh produce should not be overcomplicated. If low in pesticides standards are to be eventually introduced, “the bar should not be set too high”, as one participant put it, and the related certification paperwork should be easy to understand. If the pesticide use related standards are too complicated or too stringent, they are unlikely to be accepted in the marketplace.

Perception of food safety among farmers

The participants perceived fresh produce grown by farmers as generally safe. However, some issues were discussed concerning the definition of food safety in general, but also food safety standards, especially in relation to low pesticide risk fresh produce.

In terms of safety of pesticides, farmers, especially smallholders, do not always know how much pesticide is enough, thus encountering a potential risk of over-dosing. For example, the standards may suggest that “1.5 g of pesticide should be used per 1 ha; however, they do not always specify with how much water this 1.5 g should be diluted”. The standards do not equally indicate if the concentration of pesticides should change in “a dry or moist period”. This lack of guidance becomes particularly important considering the rapidly changing global climate with its hardly predictable local weather patterns.

The participants representing farmers reiterated that, in the HaFS sector, there were no established standards or even industry expectations on the use of pesticides. Smallholder farmers do not feel that HaFS organizations are interested in low pesticide risk fresh produce. The participants questioned: “who should take the lead in ensuring that food is safe, farmers or HaFS enterprises?” If there is no demand for low pesticide risk fresh produce, then there is no supply. HaFS enterprises should tell farmers how they expect them to grow fresh produce in terms of safety. Smallholders are likely to follow what the market says. As one participant put it: “if they say we want this [product] to be grown in this way, farmers will listen to that”.

Instead, according to the participants, more HaFS organizations were interested in organic produce and voiced expectations of what foodstuffs they needed to be grown following organic certification. However, such requirements were usually posed by the HaFS organizations representing large, international brands, such as Nando’s, or local HaFS enterprises catering for the luxury segment of the market, such as fine dining restaurants, or international tourists, such as hotels and restaurants located in major metropolitan areas. For the rest of the HaFS sector, especially SMEs, the cost of organic produce hindered its procurement.

From the perspective of farmers, the organic certification standards they used (such as the Kenya Organic Agriculture Network in Kenya or MyOrganic in Malaysia) were robust. However, the total number of farmers certified was cited as small, i.e., circa 200 in Kenya and approximately 150 in Malaysia, mostly represented by large, commercial farms or the enterprises producing small quantities of exclusive, niche food, such as jackfruit. Interestingly, in such countries as Kenya and South Africa, the farmers who could not afford organic certification, such as smallholders, provided informal peer review to each other to ensure their produce was close enough to organic standards. Such informal peer reviews were not however externally validated. If a HaFS organization were willing to procure food from such farmers, they had to trust this organic self-certification.

For some participants, organic as a marketing claim is losing its appeal. Many HaFS organizations do not understand what organic food means exactly. Also, farmers often make false claims of serving organic food. This hinders trust in organic produce among HaFS organizations. In Kenya, some smallholder Massai farmers have started growing organic and low pesticide risk fresh produce, thus indicating “growing awareness of the benefits associated with [such food production] methods among farmers”. However, these smallholders cannot afford external certification. Therefore, they can only grow and sell their produce hoping that their self-certification claims will be trusted by HaFS organizations.

According to the participants, in developing countries, there is no dedicated institution or an agency to engage farmers, especially smallholders, in growing low pesticide risk fresh produce or facilitate access of these farmers to the market. As examples of “best practice” in setting and reinforcing standards on low pesticide risk fresh produce, GlobalG.A.P and MauriG.A.P (a branch of GlobalG.A.P in Mauritius) were highlighted. Global (Citation2024) is a global certification standard for sustainable agriculture which is active in over 130 countries. Some participants were aware of it. Large, international HaFS brands, such as Nando’s, are looking for such certification when contracting farmers in developing countries. But smaller, local or national, HaFS organizations do not require such certification. GlobalG.A.P certification is mostly needed by those farmers exporting fresh produce to the international market. If supplying locally, such certification is not considered viable given its costs. The participants highlighted a complicated system of fees used by GlobalG.A.P and called for its streamlining and simplifying. GlobalG.A.P was considered expensive, especially for smallholders, and the cost factor forced “[some farmers] to leave the scheme after some time”. Smallholder farmers can achieve Global G.A.P certification, but “continuous maintenance is problematic due to the high costs of compliance, technical barriers and the need for a steady cash flow” in a sector that is vulnerable to problems such as seasonality, water shortages or pest infestations. According to some participants, to increase the appeal of GlobalG.A.P to farmers, especially smallholders, grants should be provided by national governments. Alternatively, HaFS organizations can pay or, at least, share the certification costs to reduce the financial burden on smallholders.

Lastly, according to the participants, HaFS industry associations can put more pressure on HaFS enterprises regarding the procurement of low pesticide risk fresh produce and the need to seek reassurance from their suppliers that this food meets safety standards. In this regard, HaFS industry associations can replicate what retailers do. For example, in Kenya, “retailers have voluntarily started checking their suppliers for residues to reduce food waste in the food supply chain”, thus adhering to the lean principles. This includes auditing and accrediting suppliers who have committed to food waste reduction. HaFS industry associations can follow a similar approach by commissioning audits and certifying farmers providing low pesticide risk fresh produce. The associations can also provide training on food safety to HaFS business owners and their employees.

The (dis)benefits of procuring fresh produce from smallholder farmers

The number of HaFS organizations procuring fresh produce from smallholder farmers directly was estimated as minimal. For example, in Kenya, only 5% of HaFS organizations were estimated to have collaborated with smallholders. These HaFS organizations were described by the participants as “entrepreneurial”; “risk takers or those willing to take risks”; “problem solvers”; “self-motivated”; “resilient”; “prepared to survive without some income for some time”. In such HaFS organizations, pro-sustainability and pro-social values of business owners were key for their engagement with smallholders. The same descriptions were used by the participants for smallholders supplying fresh produce directly to HaFS enterprises. The number of such smallholders was estimated as 5% of the total market in Kenya. The rest supplied fresh produce to intermediaries as this approach was considered more conventional and, therefore, “safer from the strategic and operational viewpoint”.

The paradox was articulated by some participants, i.e., when approaching smallholders with a question of why they did not serve HaFS organizations directly, the answer would be “where is the market?.” However, when approaching HaFS organizations with the question of why they did not procure fresh produce directly from smallholders, the answer would be “where is the product?” This highlights the scope to better link fresh food supply to demand and suggests that both HaFS organizations and smallholders should better signal their preparedness and willingness to collaborate.

Awareness raising campaigns and capacity-building events were called for by the participants. These were seen relevant given that many HaFS organizations were considered conservative. This explained their reluctance to switch to new suppliers or try new models of food supply chain management. The benefits of novel business approaches should be explicitly showed to HaFS organizations, ideally with the examples of best practices and the “results of a holistic cost benefit analysis”. Interestingly, large HaFS organizations may be more difficult to convince in the benefits of collaboration with smallholders. This is because of their established business models and practices. Smaller HaFS organizations may be easier to engage due to their flexibility.

Distance was seen as a major barrier to procuring fresh produce from smallholders. In the context of developing countries, where distances between production and consumption are significant, such as Indonesia and Kenya, logistical challenges prevent HaFS organizations from collaborating with smallholders. To get fresh produce from a remote location can be financially unviable and result in wastage.

The benefits of using smallholders by HaFS organizations are that “their produce is fresh and local, and easy to trace”. Some participants also perceived that smallholders had the produce of better quality because they “put their soul in its making” or since “they produce food the natural way, they still use their hands to grow”. However, contrarily, some participants claimed that commercial farmers had better or more consistent quality because of the need to follow stringent specification standards adopted within their organizations or demanded by large clients.

The disadvantage of smallholders is that their supply is unpredictable: “Once they have an abundance of things, but then nothing. Then an abundance, then nothing. Out of season they can hardly be used.” Smallholders are more vulnerable, especially in light of climatic changes. For instance, growing water scarcity is more likely to negatively affect smallholders because of the lack of organizational preparedness. Smallholders may therefore not be able to supply what they have promised, or they may not be able to commit to longer-term contracts. Commercial farmers were seen more reliable in this regard.

The key disadvantage of sourcing fresh produce from commercial farmers is that they have significant bargaining power. This can complicate collaboration, especially if a HaFS enterprise is small and needs contractual flexibility. As one participant put it: “smallholders are more agile, easier to adapt to the upcoming demand”. For instance, if a restaurant wants to change its menu to make it more seasonal or locally inspired, it may be easier to get the ’best, most authentic product from a smallholder’. Therefore, strategically, smallholders may be more challenging to work with but, operationally, they can add value to the HaFS business ecosystem.

For effective collaboration with HaFS organizations, smallholders should be organized in groups as it can be difficult to work with individual farmers due to the irregularity of supply, as discussed earlier. As one participant put it: “say, a HaFS organization wants to work with smallholders. They will ask another HaFS enterprise for recommendations, and they usually recommend a group or a cooperative of farmers rather than an individual farmer.” As a group, smallholders can beat the negative effect of seasonality by sharing their supply calendars. They can also better understand the requirements of different clients by using the word-of-mouth. Being in a group can make smallholders more accountable as they will care more about their reputation (i.e., peer pressure). A respected leader is required for groupwork to glue all smallholders together. A good leader can also obtain better contracts. In Kenya, the groupwork of smallholders was referred to by the participants as the “participatory market chain approach”. Technology, such as smartphone apps, can group smallholders and build critical mass. For example, “smart phone apps exist in South Africa that connect retailers to a pool of smallholder farmers”. The participants were not however aware of similar initiatives targeting HaFS organizations.

This suggests that smallholders require capacity building. According to the participants, capacity should be built by appropriate organizations, such as national farmer associations. When building capacity, smallholders need to develop a system of trust and reliance. As one participant described it: “The feeling of group responsibility is important to build. If one farmer cannot deliver what they have written in their contract, then they should explore alternative options such as by asking other smallholders in the group for help”. Smallholders also need training to better understand how to liaise with clients, especially represented by larger HaFS organizations, and how to meet/respond to their demands.

Importantly, from the smallholder perspective, price guarantee provided by existing clients, especially large retailers, plays an important role in deciding whether to grow more fresh produce and supply it to alternative markets. The question they face is “Why do I need to produce more, if I have a guaranteed price from a big brand to buy a certain amount? I just sell all my produce to them”. Price guarantee operated by large retailers may therefore prevent smallholders from expanding their market to HaFS enterprises.

Governments can be more actively involved in building capacity of HaFS organizations to work with smallholders. However, in such countries as Indonesia this involvement should be undertaken with caution. Such issues as corruption and distrust in public institutions can be off-putting. If distrust is not an issue, then the role of governments should be concerned with auditing and monitoring compliance with food safety standards, but also providing education and training to HaFS business owners and smallholder farmers on what fresh produce can be considered low pesticide risk.

Non-governmental organizations active in the field of agriculture and poverty alleviation can also aid in linking HaFS organizations to smallholders. Examples of small-scale and short-term projects in Malaysia were given by the participants where HaFS enterprises were connected to smallholders by not-for-profit organizations in pursuit of local community benefits, such as fresh produce provisioning. However, the funding of non-governmental organizations is limited and, once it is over, the situation often reverts to “normal whereby HaFS organizations re-start working with their intermediaries”, as one participant put it.

Lastly, referring to the triple-bottom line sustainability perspective, some participants questioned the benefits of smallholder farming arguing that the media had created a too negative image of commercial farmers. For instance, one participant asked: “what is better from holistic sustainability, a farmer who plants a limited number of fresh products in their back garden, or a farmer who employs 100 people from their local community?” A smallholder may not necessary be economically sustainable because of the issue of seasonality. Additionally, most smallholders rely on pesticides to grow enough fresh produce, so they may not be sustainable from the environmental perspective. Contrarily, the production of a commercial farmer who employs 100 local people will be more economically viable because of the larger scale which can diversify the sources of revenue depending on seasons. Moreover, commercial farmers, through employment, may be better positioned to support local communities, thus advancing the social dimension of sustainability. The participants called for a holistic assessment to examine if, from the triple bottom-line sustainability perspective, fresh, low pesticide risk, produce grown by smallholders is more beneficial compared to the commercial production.

SFSCs and AFNs

When discussing SFSCs as alternative business models enabling better collaboration between HaFS organizations and smallholders, these were well understood by the participants. SFSCs were seen positively, but idealized: “the concept is wonderful, but it’s very challenging to create and proof-test a [SFSC] business model that will work effectively and long term in practice”. The participants argued that it was only a small subset of people who would be prepared to “go against the flow and do something different, something less mainstream”, such as SFSCs. This emphasized the importance of personal values of HaFS business owners and smallholders for engaging in SFSCs.

SFSCs were considered good for building capacity of local communities, so their benefits extended beyond farming and HaFS. SFSCs could also provide empowerment to its members. However, the question frequently asked by the participants was “how to mobilise different actors [smallholder farmers and HaFS SMEs] within a SFSC?” and “how to build capacity?”

The participants argued that SFSCs could play an increasing role in the future. This was attributed to the growing sustainability awareness of HaFS organizations, especially among large international chains. Higher demand for the food supply chains that are more lean, transparent, resilient, and, therefore, sustainable was anticipated. Close relationships with suppliers facilitated by SFSCs were considered beneficial for HaFS organizations. There would be more trust in the food supply chain which could reinforce the capital of its participants, thus boosting the overall business resilience.

However, according to the participants, currently, SFSCs were largely marketed as the models of food supply chain management that were primarily concerned with the provision of local rather than low pesticide risk fresh produce. As one participant explained it: “People like the idea of local food. Customers like it too. They are willing to pay more for local food. When guests come to a hotel and read: This fruit was grown 5 km down the road, this is great. Customers want to know they support local communities, and this is what this concept [SFSC] promotes”. This highlights the potential for low pesticide risk fresh produce to be integrated in the marketing of SFSCs. By positioning themselves as the business models provisioning local and safe food, SFSCs can enhance their appeal to multiple actors, thus encouraging collaboration.

Climate change was one of the reasons why SFSCs could become more popular in the future. The increasingly vulnerable nature of global food supply may require the alternatives located closer to where HaFS organizations are based. Such alternatives should be more responsive and responsible. Climate change may even require HaFS enterprises to grow their own fresh produce. However, such practices will be insufficient in terms of “the volume and variety of the food grown”. This notwithstanding, examples and case studies of HaFS organizations either growing their own food or working with local smallholders were deemed important for “ … educating people and winning their custom … but also showcasing the business commitment to sustainability and local community values”.

As for AFNs, these were less understood by the participants with only a few being familiar with this concept. Most participants asked for explanations to better understand how AFNs functioned. When explained, many agreed it would be an interesting business model to test although the majority highlighted the same limitation as applied to SFSCs, namely, “great conceptualisation but lacking examples of the practical application”.

Lastly, some participants discussed SFSCs and AFNs in the context of regenerative tourism, regenerative agriculture, and regenerative hospitality which were referred to as the novel concepts with the potential to reshape the future of food supply chain in the HaFS sector. These paradigms emphasize the benefits provided by HaFS organizations and smallholders to local communities that extend beyond profit-making. For example, employment of disadvantaged individuals or responsible use of pesticides can facilitate the regeneration of local communities and conserve the environment. The participants highlighted how such stakeholders as national farmer associations and academics encouraged farmers to grow food considering local soil characteristics i.e., without exceeding soil capacity to produce a certain amount of food per time. Protecting soil, restoring and maintaining its fertile capacity was considered paramount for the economic well-being of smallholders and environmental conservation of the area in which they operated: “you need to give back to nature what you’ve taken from it. This will sustain your ability to produce, to stay competitive.” The future of regenerative business models was considered bright, and HaFS organizations were urged to carefully watch this trend as it could become a potential market disruptor.

Discussion and concluding remarks

This study explored the opportunities and challenges of the provision of low pesticide risk fresh produce by smallholder farmers to HaFS organizations. Stakeholder theory was used to guide the study’s design and analysis given that collaboration is critical to ensure that HaFS enterprises can work directly with smallholders. The study’s findings shed light on the impediments of stakeholder collaboration and highlighted the scope for increasing its effectiveness.

The findings indicate that HaFS organizations do not consider low pesticide risk fresh produce as an operational or strategic priority and such attributes of food as local, seasonal, and low carbon hold stronger appeal. The food procured is considered safe by definition, and intermediaries are assumed to take responsibility for ensuring that fresh produce is safe from the perspective of pesticide use. As a result, there are no industry standards or even business expectations on the procurement of low pesticide risk fresh produce in the HaFS sector. Importantly, this finding applies to all HaFS markets considered in the current study i.e., in developed and developing countries, thus indicating that a lack of industry attention paid to the issue of low pesticide risk fresh produce prevails across borders.

The study contributes to knowledge by revealing potential risks of serving fresh produce to HaFS customers containing excessive concentrations of pesticides. Ridderstaat and Okumus (Citation2019) and Lee and Liu (Citation2020) report on the results of safety audits in HaFS enterprises and highlight pesticides as a critical issue to watch in the future. These two studies are however concerned with the “ex post” assessment of food safety. No research has been undertaken to understand if/how HaFS organizations apply proactive, “ex ante,” measures to ensure the products they serve are low pesticide risk.

This current study underscores the need to oversee the HaFS market regarding pesticide use in fresh produce served to customers. This need exists in the HaFS markets in both developed and developing countries where, despite potential differences in how food is provisioned to HaFS organizations, the issue of low pesticide risk fresh produce is paid insufficient attention to. The overreliance of HaFS organizations on intermediaries and ex post safety assessments creates the opportunities for high pesticide risk fresh produce to appear on customer plates, thus undermining quality management. The introduction of industry standards or, at least, voluntary agreements and business commitments, on the use of pesticides in fresh produce supplied to HaFS organizations can reduce the risk of mortality and morbidity, thus ensuring consumer safety and contributing to business longevity. These industry standards should be designed in HaFS markets of both developed and developing countries as provision of low pesticide risk fresh produce is equally vital for consumer safety in national as well as international markets. It is important to codesign these standards/agreements/commitments with the industry needs and resources in mind. For example, the varied resource base of SMEs and large international chains should be considered. HaFS industry associations can lead on this codesign by engaging various actors of the HaFS food supply chain, understanding their needs and expectations, and disseminating standards to the industry.

The study shows that most HaFS organizations, either in developed or developing countries, do not engage in practices of sourcing fresh produce directly from smallholder farmers. The lack of bargaining power among smallholders, their low critical mass resulting in the insufficient capacity to satisfy demand, contractual obligations toward major retailers, logistical issues, and the negative effect of seasonality represent the main determinants of disengagement. Literature has highlighted the restricted scope of collaborative work between smallholders and other actors of the food supply chain, especially from the perspective of safe farm produce provisioning (Duarte Alonso & O’Neill, Citation2010; Roy et al., Citation2017). The contribution of the current study is in underscoring the key factors which hinder collaboration between HaFS organizations and smallholders, thus paving the way for the design of interventions to enable collaborative work between these actors. These interventions can be co-designed by engaging multiple stakeholders accounting for their variable interests and resources availability.

For example, the current study demonstrates that capacity-building initiatives are required for better engagement of smallholders and HaFS organizations in the provision of low pesticide risk fresh produce. National HaFS industry and farmer associations are instrumental for organizing such initiatives, especially in developing countries where other stakeholders, such as governments, may have gained limited public trust. The study also highlights the potential of technology, such as smartphone apps, but also BCT and AI, to be harnessed for building the critical mass of smallholders, connecting them to HaFS organizations and increasing transparency and traceability. The literature has recognized that technological innovations can make global food supply chains more sustainable and build trust among their actors, especially those in disadvantaged positions, such as smallholders (Kumarathunga et al., Citation2022). This current study offers further empirical evidence calling for the design of tailor-made technological interventions to engage smallholders and HaFS organizations. This engagement can benefit the provision of local and seasonal food as well as low pesticide risk fresh produce. This engagement can make food supply chains more resilient which is critical in light of the ongoing environmental changes which can disrupt the traditional models of food supply chain management.

This study indicates that alternative models of food supply chain management that can make food systems more lean, resilient and sustainable, such as SFSCs and AFNs, have limited industry appeal. Although the demand for such models can increase in the future, currently, there is a need for testing the feasibility of engaging multiple actors in SFSCs and AFNs, potentially with the aid of technology. Examples and case studies of the effectively designed and implemented models in developed but, especially, developing countries can help HaFS organizations and smallholders understand their (dis)benefits. Models that have proven feasible in specific localities will need to be carefully examined to ensure their adoption for upscaling and application in other political and socio-economic contexts. Therefore, this current study contributes to the growing body of literature on the role of SFSCs and AFNs in the future food systems (Giampietri et al., Citation2016; Gori & Castellini, Citation2023). The current study highlights that these models are currently too idealized and need empirical validation to become mainstream.

The study also outlines the potential of other, more sustainable, business model alternatives, such as regenerative agriculture, tourism and hospitality, to be tested through empirical research. Given the growing interest among HaFS organizations and their customers in reducing the environmental impact of operations and benefitting host communities, it is necessary to examine how various, regeneration-driven, business innovations can contribute to the design of more resilient, sustainable and safer food supply chains. The potential of regenerative business models should especially be investigated in the HaFS markets of developing countries. This is because extant research on regenerative business models has focused on developed nations (Konietzko et al., Citation2023). Yet, developing countries need an urgent shift toward (more) sustainable and circular business practices given the extensive levels of environmental pollution and degradation experienced within (Goyal et al., Citation2018). Studies of regenerative business models in the sectors of HaFS, tourism and agriculture of developing economies can outline the determinants of their adoption and support by relevant stakeholders, including owners/managers of HaFS enterprises, employees, policymakers, and consumers.

Lastly, this study had limitations that should be addressed in future research. First, the findings were derived from a limited number of interviews conducted with different actors of HaFS food supply chains. Further, the geographical scope of analysis was limited to selected countries in Europe, Africa and South East Asia. Lastly, the focus was on fresh farm produce and pesticide use while other types of agricultural products and polluting substances that could contribute to morbidity and mortality were excluded from analysis. Future studies should extend the scale of examination to make it more comprehensive, thus adding novel insights and enabling more generalizable conclusions to be drawn.

Supplementary material Pesticide low risk produce.docx

Download MS Word (16.8 KB)Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the CABI-led PlantwisePlus programme, which is financially supported by Directorate-General for International Cooperation (DGIS), Netherlands; European Commission Directorate General for International Partnerships (INTPA, EU); the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO), United Kingdom; and the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/15378020.2024.2372483

Additional information

Funding

References

- Al-Aomar, R., & Hussain, M. (2018). An assessment of adopting lean techniques in the construct of hotel supply chain. Tourism Management, 69, 553–565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.06.030

- Ali, M. H., Tan, K. H., & Ismail, M. D. (2017). A supply chain integrity framework for halal food. British Food Journal, 119(1), 20–38. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-07-2016-0345

- Al Kaabi, A., Al Mazrouei, A., Al Hamadi, S., Al Yousuf, M., & Taylor, E. (2015). Knowing the status: Gathering baseline data on food safety management across the Abu Dhabi hospitality industry. Worldwide Hospitality & Tourism Themes, 7(1), 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1108/WHATT-12-2014-0038

- Al Khaja, M., Al Muhairi, M., Al Yousuf, M., Al Mazrouei, A., Ali, M. I., Taylor, E., & Eunice Taylor, D. (2015). Developing a solution for small businesses: The creation of Salamt Zadna, a unique food safety management system for small businesses in Abu Dhabi. Worldwide Hospitality & Tourism Themes, 7(1), 63–77. https://doi.org/10.1108/WHATT-12-2014-0043

- Al Yousuf, M., Bin Salem, S., Abdi Ali, B., Saleib, M., Juwaihan, H., Taylor, E., & Eunice Taylor, D. (2015). Setting the standard: The development of bespoke guides for HACCP-based food safety management systems for different sectors of the hospitality industry. Worldwide Hospitality & Tourism Themes, 7(1), 33–49. https://doi.org/10.1108/WHATT-12-2014-0039

- Arendt, S. W., Paez, P., & Strohbehn, C. (2013). Food safety practices and managers’ perceptions: A qualitative study in hospitality. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 25(1), 124–139. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596111311290255

- Aworh, O. C. (2021). Food safety issues in fresh produce supply chain with particular reference to sub-Saharan Africa. Food Control, 123, 107737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2020.107737

- Baert, K., Van Huffel, X., Jacxsens, L., Berkvens, D., Diricks, H., Huyghebaert, A., & Uyttendaele, M. (2012). Measuring the perceived pressure and stakeholders’ response that may impact the status of the safety of the food chain in Belgium. Food Research International, 48(1), 257–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2012.04.005

- Benedek, Z., Fertő, I., & Molnár, A. (2018). Off to market: But which one? Understanding the participation of small-scale farmers in short food supply chains—A Hungarian case study. Agriculture and Human Values, 35(2), 383–398. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-017-9834-4

- Bhattacharya, A., & Fayezi, S. (2021). Ameliorating food loss and waste in the supply chain through multi-stakeholder collaboration. Industrial Marketing Management, 93, 328–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2021.01.009

- Bui, T. N., Nguyen, A. H., Le, T. T. H., Nguyen, V. P., Le, T. T. H., Tran, T. T. H., Nguyen, N. M., Le, T. K. O., Nguyen, T. K. O., Nguyen, T. T. T., Dao, H. V., Doan, T. N. T., Vu, T. H. N., Bui, V. H., Hoa, H. C., & Lebailly, P. (2021). Can a short food supply chain create sustainable benefits for small farmers in developing countries? An exploratory study of Vietnam. Sustainability, 13(5), 2443. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052443

- Campbell, J. L., Quincy, C., Osserman, J., & Pedersen, O. K. (2013). Coding in-depth semistructured interviews: Problems of unitization and intercoder reliability and agreement. Sociological Methods & Research, 42(3), 294–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124113500475

- Cha, J., & Borchgrevink, C. P. (2019). Customers’ perceptions in value and food safety on customer satisfaction and loyalty in restaurant environments: Moderating roles of gender and restaurant types. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 20(2), 143–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/1528008X.2018.1512934

- Chiaverina, P., Drogué, S., & Jacquet, F. (2024). Do farmers participating in short food supply chains use less pesticides? Evidence from France. Ecological Economics, 216, 108034. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2023.108034

- Chiaverina, P., Drogué, S., Jacquet, F., Lev, L., & King, R. (2023). Does short food supply chain participation improve farm economic performance? A meta‐analysis. Agricultural Economics, 54(3), 400–413. https://doi.org/10.1111/agec.12764

- Cho, M., Bonn, M. A., Giunipero, L., & Jaggi, J. S. (2017). Contingent effects of close relationships with suppliers upon independent restaurant product development: A social capital perspective. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 67, 154–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.08.009

- Clark, J., Crandall, P., & Reynolds, J. (2019). Exploring the influence of food safety climate indicators on handwashing practices of restaurant food handlers. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 77, 187–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.06.029

- Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2017). Thematic analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(3), 297–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1262613

- Dania, W. A. P., Xing, K., & Amer, Y. (2018). Collaboration behavioural factors for sustainable agri-food supply chains: A systematic review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 186, 851–864. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.03.148

- De Andrade, M. L., Stedefeldt, E., Zanin, L. M., Zanetta, L. D., & Da Cunha, D. T. (2021). Unveiling the food safety climate’s paths to adequate food handling in the hospitality industry in Brazil. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 33(3), 873–892. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-09-2020-1030

- DeLind, L. B., & Howard, P. H. (2008). Safe at any scale? Food scares, food regulation, and scaled alternatives. Agriculture and Human Values, 25(3), 301–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-007-9112-y

- Djekic, I., Batlle-Bayer, L., Bala, A., Fullana-I-Palmer, P., & Jambrak, A. R. (2021). Role of the food supply chain stakeholders in achieving UN SDGs. Sustainability, 13(16), 9095. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169095

- Duarte Alonso, A., & O’Neill, M. (2010). Small hospitality enterprises and local produce: A case study. British Food Journal, 112(11), 1175–1189. https://doi.org/10.1108/00070701011088179

- ETC Group. (2022). Food Barons 2022. Crisis profiteering, digitalization and shifting power. Retrieved from March 9, 2024. https://etcgroup.org/content/food-barons-2022

- Eversham, E. (2021). Restaurant cleanliness more important than customer service, finds report. Retrieved January 13, 2024, from https://www.restaurantonline.co.uk/Article/2016/09/12/Restaurant-cleanliness-more-important-than-customer-service-finds-report

- FAO. (2024). Food safety and quality. Retrieved June 11, 2024, from https://www.fao.org/food-safety/en/

- Filimonau, V., & Ermolaev, V. A. (2021). Mitigation of food loss and waste in primary production of a transition economy via stakeholder collaboration: A perspective of independent farmers in Russia. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 28, 359–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2021.06.002

- Filimonau, V., & Ermolaev, V. A. (2022). Exploring the potential of industrial symbiosis to recover food waste from the foodservice sector in Russia. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 29, 467–478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2021.10.028

- Filimonau, V., & Krivcova, M. (2017). Restaurant menu design and more responsible consumer food choice: An exploratory study of managerial perceptions. Journal of Cleaner Production, 143, 516–527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.12.080

- Food Standards Agency. (2017). Hazard analysis and critical control point (HACCP). Retrieved January 13, 2024, from https://www.food.gov.uk/business-guidance/hazard-analysis-and-critical-control-point-haccp

- Garner, B., & Ayala, C. (2019). Regional tourism at the farmers’ market: Consumers’ preferences for local food products. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 13(1), 37–54.