Abstract

Background

PrEP has the potential to combat HIV epidemic among Adolescent Girls Young Women (AGYW) in sub-Saharan Africa. This study aimed to review research focusing on AGYW experiences and challenges related to PrEP use to promote prevention programmes.

Methods

The PRISMA guidelines were used to direct the search, data collection, synthesis and review. PubMed and Embase databases were searched to identify recent studies that used qualitative approaches to report on the experiences of AGYW in using PrEP.

Results

The use of PrEP was associated with a believe that AGYW were having multiple sexual partners. These misconceptions made it difficult for AGYW to disclose the use of PrEP to sexual partner and families and compelled them to conceal it. The use of PrEP enacted agency, empowerment and self-worth among AGYW.

Conclusion

AGYW ability to exercise decision on the initiation of PrEP and adherence to the course required convenient and supportive context.

Background

Recent data from UNAIDS showed that Adolescent Girls and Young Women (AGYW) in sub–Saharan Africa are at increased risk of acquiring HIV infection, accounting for 63% of all new infections in the region (UNAIDS, Citation2023). Eastern and Southern Africa and West and Central Africa regions reported higher rates of new HIV infection among AGYW. According to UNAIDS, the estimated new HIV in AGYW were 70%-80% of the total HIV infection in this age category (UNAIDS, Citation2023). These rates reflect multiple societal, economic and cultural biases around HIV and excessive vulnerability of AGYW in the African context. Different gender and power dynamics impacted AGYW ability to take decision on their bodies and sexual life. Research reported that AGYW are less likely to imply safe sex by using protection (Chabata et al., Citation2020; Chapman et al., Citation2019; Duby et al., Citation2021).

In effort to reduce the burden of HIV on AGYW, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for the prevention of HIV was promoted to protect a generation from the devastating effect of HIV and AIDs. PrEP is considered as a scientific breakthrough, and it was recommended by World Health Organization to be provided to all persons at substantial risk of HIV infection (Grant et al., Citation2010; Smith et al., Citation2012; U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Citation2012; World Health Organization, Citation2012, Citation2015). PrEP is increasingly considered as a critical component of comprehensive HIV preventive programmes. The oral type of PrEP requires regular intake to provide protection against HIV. Many African countries with high rates of new HIV infection among AGYW established programmes to provide PrEP to this age group. However, after years of availability, AGYW still carry the extensive burden of new HIV infection (UNAIDS, Citation2023). This low impact could have been related to different contextual factors related to PrEP settings including access and convenience. Reports outlined challenges facing AGYW in disclosing PrEP to sexual partners, family and peers because of different misconceptions and judgmental behaviors related to PrEP. AGYW experienced barriers which seemed to outweigh their ability to prioritize their health and protection. A recent study from Kenya reported that PrEP continuation among high risk population including AGYW was 29–32% in month 1 and dropped to 6–8% in month 3 (Were et al., Citation2020). A systematic review by Sidebottom et al., reported an adherence rate ranging between 29 and 76% in most African countries (Sidebottom et al., Citation2018). Clear understanding to the complex factors that affect the uptake and adherence of AGYW to PrEP remain essential to enhancing the service delivery this preventive treatment. This study aims to review empirical research focusing on AGYW experiences and challenges related to PrEP in sub-Saharan Africa to promote best practices in prevention programmes.

Methods

This systematic review has considered studies that used qualitative approaches to report on the experiences and challenges related to PrEP in AGYW in sub-Saharan Africa. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines were used to direct the search, data collection, synthesis and review of findings (Page et al., Citation2021).

Inclusion criteria

Qualitative studies were eligible if they have been performed in the sub-Saharan Africa. All qualitative research that reported on the experiences and challenges of AGYW related to PrEP were included. Studies which presented qualitative data analysis as a part of other data collection were also considered for inclusion. The phenomena of interest were experiences and challenges related to PrEP for the prevention of HIV. This included studies performed on AGYW who were enrolled in the PrEP programmes or thinking to enroll. It also included AGYW who declined PrEP or interrupted the course. Eligible studies must have used in-depth interviews, focus groups or both. Studies from Jan 2020 until August 2023 were included to report on the most recent experiences with PrEP. During the preliminary search, no studies before 2020 were found. Therefore, the inclusion timeframe was set to include this year and beyond. Lacking research before 2020 might be influenced by delays in scaling up PrEP use in AGYW age category in sub-Saharan Africa.

Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded if they examined experiences of African women outside of the sub-Saharan Africa. Studies were excluded if they were assessing the opinion of different stakeholders including healthcare providers, families and peers. Studies were excluded if they were examining selective groups including sex workers, transgender women, drug users, homeless or incarcerated women because of different context. Only original articles published in peer-review journal were included and results from grey literature were excluded. demonstrates the final inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Search strategy

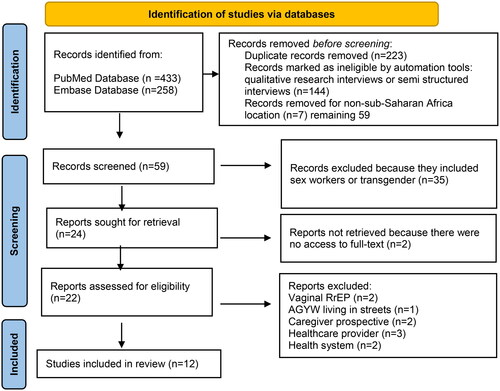

The literature search was conducted in August 2023 using PubMed and Embase databases. Details of search strategy are included in textbox 1. The initial search retrieved a total of 691 published records. Out of them, 433 were from PubMed and 258 were from Embase. By eliminating 223 duplicates, the remaining 210 records were screened by selecting qualitative studies or interview/semi-structured interviews and removing non-qualitative studies. This resulted in eliminating 144 records. The remaining 59 records were screened by reviewing the titles and abstracts to verify their eligibility. Further 35 studies were excluded based on ineligible study participants. Additional 2 records were not retrieved because there was no access to full text. After reading the full text for the remining 22 records, an exclusion of another 10 studies was done. Reasons for exclusion included: assessing the healthcare system/providers, assessing caregivers, or assessing vaginal ring modality of PrEP. Last study was excluded because AGYW which were included were on the streets/homeless. The rationale for exclusion was based on differences in social and economic context. Search was performed by the two researchers independently and was cross-checked before finalizing it. There was inconsistency between the 2 researchers in 2 studies, which required reviewing the full text of these 2 studies to take final decision. Both studies were excluded based on the exclusion criteria and no changes has been applied.

Textbox 1. Details of search strategy

Risk of bias assessment

The risk of publication bias was assessed by using Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool for qualitative studies (Long et al., Citation2020). After reading the full text of all selected articles, the quality of the methodology of each article was evaluated as ‘yes’, ‘cannot tell’ or ‘no’. Studies were considered for inclusion if they pass 8 out of 10 assessment criteria. After extracting the relevant information, all studies showed high quality and satisfied the criteria. However, most studies provided no clarification on the relationships between the researcher and participants. Details on the quality assessment are listed in .

Table 2. Assessment of risk of bias and quality of included studies by CASP tool (Long et al., Citation2020).

Data extraction and analysis

The data from each study was extracted and collated into Microsoft Excel spreadsheets. Domains used to organize data included study title, place, and design, participant age, sample size, study context, and findings on experiences and challenges related to PrEP. Analysis was guided by grouping the narrative into categories on key themes related to experiences and challenges reported by AGYW. These were on three areas of challenges including: disclosure related, enablers and barriers and healthcare- related experiences. A table was used to summarize the findings including quotes from the original articles.

Results

Characteristics of the included studies

There were 12 studies included in the current review. As seen in , all the studies researched AGYW experiences with PrEP in sub-Saharan Africa context. A PRISMA flowchart describing the systematic search is included in . Among the studies, there were 3 from South Africa (Giovenco et al., Citation2021; Haribhai et al., Citation2023; O’Rourke et al., Citation2021), two from Namibia (Barnabee et al., Citation2022; Vasco & Crowley, Citation2022), one from each of the following countries; Malawi (Maseko et al., Citation2020), Kenya (Pintye et al., Citation2021), Uganda (Kayesu et al., Citation2022), Eswatini (Bjertrup et al., Citation2021), Tanzania (Jani et al., Citation2021) and Zimbabwe (Velloza et al., Citation2020). Final study has reported on two centers; South Africa and Kenya (Rousseau et al., Citation2021). Most studies included AGYW of the age group 15–25 years. However, Kayesu et al., in Uganda included even the age of 14 years (Kayesu et al., Citation2022). On the other hand, Vasco and Crowley from Namibia reported on young women 21–24 only (Vasco & Crowley, Citation2022). All studies covered AGYW alone except of Jani et al., who included opinion of male partners as well (Jani et al., Citation2021). Generally, the included studies were based in a mix of clinical and community settings. Most studies recruited AGYW who were enrolled in different PrEP initiatives. Out of all studies, Haribhai et al., and Pintye et al., included AGYW in settings related to maternal and child healthcare (Haribhai et al., Citation2023; Pintye et al., Citation2021). All studies followed qualitative methodology, except of Barnabee et al., which was mixed methods (Barnabee et al., Citation2022). Data analysis used in the included studies was thematic analysis or narrative synthesis.

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart for the selection process (Page et al., Citation2021).

Table 3. Findings related to challenges to PrEP use in AGYW in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Challenges related to disclosure of PrEP use

Stigma associated with PrEP use was reported by AGYW interviewed in the included studies. The perceived stigma originated from tendency of others to believe that PrEP was a treatment for HIV infection rather than a preventive measure. Furthermore, using PrEP prevention in AGYW was linked to suspicion of having multiple sexual partners among these women. Most AGYW experienced difficulties in disclosing PrEP use to partners for fears of assumption of sexual infidelity (Jani et al., Citation2021; Kayesu et al., Citation2022; Maseko et al., Citation2020; Rousseau et al., Citation2021; Velloza et al., Citation2020). A participant from Namibia, quoted “I didn’t tell him, I was just scared he would question me a lot. He might think that I am only using it because I want to sleep around with men or I don’t trust him or something.” (Vasco & Crowley, Citation2022).

AGYW applied different strategies to disclose the use of PrEP including selecting who they trust and felt comfortable sharing with (Rousseau et al., Citation2021). Many AGYW reported arguments with sexual partners leading sometimes to violence or ending the relationship (Bjertrup et al., Citation2021; Giovenco et al., Citation2021; Haribhai et al., Citation2023; Jani et al., Citation2021; Kayesu et al., Citation2022; Velloza et al., Citation2020). Fears of sexual partner reactions led to decision to conceal PrEP, (Rousseau et al., Citation2021), sometimes using strategies such as exchanging the container (Pintye et al., Citation2021). On the other hand, AGYW felt assured when parents supported them and motivated them to adhere (Bjertrup et al., Citation2021; Haribhai et al., Citation2023; Pintye et al., Citation2021). In some cases, AGYW preferred to disclose PrEP treatment to female members of their families but not a male one (Vasco & Crowley, Citation2022). Mother’s support was encouraging (Rousseau et al., Citation2021). Disclosing the use of PrEP to fathers was less common but brought supportive reaction from them (Giovenco et al., Citation2021). One AGYW participated in Haribhai et al., study mentioned “[My mother] said I should take [PrEP]. and I should not mind anyone who says I have HIV [stigmatization]. [She said that PrEP] should not leave our home.” Age 21 (Haribhai et al., Citation2023).

Conversely, parental rejection and fears of promiscuous status of AGYW prevented them from disclosing PrEP to parents (Jani et al., Citation2021; Maseko et al., Citation2020; Vasco & Crowley, Citation2022). Furthermore, pressure from family members seemed to affect the uptake and adherence of PrEP (Bjertrup et al., Citation2021; Kayesu et al., Citation2022; O’Rourke et al., Citation2021; Velloza et al., Citation2020). Peer support facilitated by ‘adherence clubs’ was appreciated and increased adherence (Barnabee et al., Citation2022; O’Rourke et al., Citation2021). Disclosure to a friend who believes in the value of PrEP brought supportive reactions (Giovenco et al., Citation2021). However, peers with inaccurate knowledge of PrEP discouraged AGYW by spreading misconceptions about this treatment (Barnabee et al., Citation2022).

Challenges related to motivators and barriers of PrEP use

AGYW viewed PrEP utilization as a personal value associated with a happy feeling of HIV negative status (Bjertrup et al., Citation2021; Haribhai et al., Citation2023; Jani et al., Citation2021; O’Rourke et al., Citation2021; Vasco & Crowley, Citation2022). PrEP enacted agency, empowerment, and self-worth among AGYW (Bjertrup et al., Citation2021; Rousseau et al., Citation2021). Being aware of the risk of acquiring HIV and perception of vulnerability acted as motivators to use PrEP (Rousseau et al., Citation2021; Vasco & Crowley, Citation2022). AGYW who were adherent to PrEP reported greater agency and dynamics around sex (Jani et al., Citation2021; Rousseau et al., Citation2021). PrEP was perceived as a protective tool to reduce the control of the sexual partner who may dislike condoms (O’Rourke et al., Citation2021). Rousseau et al., quoted “I feel relaxed because that risk of getting HIV I have controlled.” Age 19 (Rousseau et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, results shows that AGYW perceived PrEP as a safeguard to incidents of non-consensual sex with someone of unknown HIV status or in situations where AGYW found difficulties in persuading sexual partner to use condom (Haribhai et al., Citation2023; Pintye et al., Citation2021). Jani et al., reported that AGYW who distrust their sexual partners’ faithfulness to the sexual relationships were interested in PrEP (Jani et al., Citation2021). AWYG commented “my husband moves to different places and I can’t know if he has other partners.” Age 21 (Jani et al., Citation2021). Pregnant AGYW who used PrEP perceived the adherence as a protective strategy to save their infants where a boyfriend might be having multiple sexual partners (Haribhai et al., Citation2023). Results highlighted different challenges originating from wrong information regarding PrEP including a misconception that PrEP causes infertility (Kayesu et al., Citation2022; Vasco & Crowley, Citation2022) or affect productivity (Maseko et al., Citation2020), or causes resistance to ART if contracted HIV at any stage (Pintye et al., Citation2021).

Challenges related to healthcare providers, information and pill taking

Initiation of PrEP depends on the ease of access to the programme (Maseko et al., Citation2020). Most programmes were perceived as accessible and employed supportive healthcare teams (Barnabee et al., Citation2022; Haribhai et al., Citation2023; Rousseau et al., Citation2021; Vasco & Crowley, Citation2022; Velloza et al., Citation2020). AGYW suggested PrEP services to be offered in youth-friendly settings or clinics set aside from the main facility serving adult patients (Maseko et al., Citation2020). AGYW who received PrEP in the centers offering ART had to endure being seen as HIV-positive (Vasco & Crowley, Citation2022). Taking lifelong PrEP pill was perceived by AGYW as a cognitive burden (Rousseau et al., Citation2021). Pintye et al., quoted “Taking PrEP [pills daily], in fact it is a burden, it is not easy. I prefer you inject me instead of giving me pills.” Age 23 (Pintye et al., Citation2021). AGYW favored packaging PrEP in the appearance of medications for common ailments to help them conceal the use (Maseko et al., Citation2020). Velloza et al., reported that PrEP which used discreet pill carrying cases that looked like cosmetics bags was appreciated by AGYW (Velloza et al., Citation2020). The size of PrEP pills made them difficult to swallow (Pintye et al., Citation2021; Rousseau et al., Citation2021). Some AGYW preferred alternative form of PrEP administration such as injections (Pintye et al., Citation2021). Side effects were challenging for AGYW and were associated with a decision to interrupt PrEP (Kayesu et al., Citation2022; Maseko et al., Citation2020; O’Rourke et al., Citation2021; Rousseau et al., Citation2021). Strategies to deal with side effects included adjusting the time of taking the pill or seeking help from clinic staff (O’Rourke et al., Citation2021). Judgment and stigma from the healthcare providers was reported by AGYW (Barnabee et al., Citation2022). A participant interviewed by Barnabee et al., mentioned “Then I said, “I’m taking PrEP because I don’t want to get HIV.’ Then he said, “why… are you not like having one partner?’ Then I said, “I’m having.” “And is your partner having HIV?” Then I said no, then he said, “oh, so why are you taking it? PrEP is for only people that they are in a relationship whereby one partner is [living with] HIV.” Then I said, “you never know, maybe your partner is lying to you.” Then he said ok, then he gave me, then I went home.” Age 24 (Barnabee et al., Citation2022). AGYW valued community services which offered flexibility of getting PrEP refills (Barnabee et al., Citation2022).

Discussion

This systematic review sought to examine challenges facing AGYW in relation to using PrEP for the prevention of HIV in a high incidence setting. The provision of PrEP to AGYW is fundamental to control HIV epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa. The number of PrEP initiatives in the region was scaling up over the last few years especially where a government approval was processed (PrEPWatch, Citation2023). Nonetheless, local policies still affect the ability of AGYW to access PrEP and changes such as widening the eligibility and lowering age of consent have positive impact on uptake of PrEP (Irungu & Baeten, Citation2020; Patel et al., Citation2022; Tailor et al., Citation2022). Despite the importance of PrEP, there are many countries in sub-Saharan Africa, with no report on uptake of this preventive strategy (Irungu & Baeten, Citation2020; PrEPWatch, Citation2023). The current review reported on 8 sub-Saharan Africa countries, highlighting the scarcity of information from the remaining African nations. According to UNAIDS, only 42% of districts with very high HIV incidence in sub-Saharan Africa were covered with dedicated prevention programmes for AGYW (UNAIDS, Citation2023). Therefore, future research should explore challenges to implementation of PrEP programmes in these African nations.

This review has shown a general state of fear among AGYW interviewed in the included studies. The fears seemed to originate from gender inequality and misconceptions around PrEP. Patriarchal patterns of social disempowerment manifested in men’s control over AGYW lives and access to PrEP treatment. Fears were drivers to prevent AGYW from seeking PrEP or declining it when offered the treatment (Giovenco et al., Citation2021; Pintye et al., Citation2021; Velloza et al., Citation2020). AGYW feared men’s rejection to their decision to use PrEP. This rejection was paired with verbal and emotional abuses as well as violence against AGYW who decided to use PrEP. Patriarchal trends in sub-Saharan Africa, were reported to disadvantage AGYW in different aspects of HIV testing, prevention and treatment services (Crowley et al., Citation2022; Murewanhema et al., Citation2022; Ninsiima et al., Citation2018).

The results of the current review demonstrated a common misconception between sexual partners, families and communities that PrEP was a treatment for HIV infection rather than a prevention against the infection. This confusion flared the stigmatizing attitudes and hindered AGYW ability to access PrEP. Typically, misconceptions are supposed to be addressed at the commence of the new HIV preventive strategy by offering clear and effective information to the public. The results of the current review suggest that AGYW were invited to use PrEP in communities deficient in accurate information. Delays in tackling these misconceptions impede the progress of PrEP initiatives and urgent interventions to address the prevailing concepts are necessary.

Results of the current review reflected the presence of social control mechanisms impacting AGYW decision to disclose the use of PrEP to inner and outer social circles. Disclosing the use of PrEP to sexual partner, family and peers known to increase adherence (Beesham et al., Citation2022; Ojeda et al., Citation2019). The results of the current review highlighted different experiences with disclosure of PrEP to family and peers, ranging from support to rejection. The experience with disclosure reflected the intensity of circulating misconceptions. Seeking to generate support, AGYW used very selective strategy in disclosing (Campbell & Mannell, Citation2016; Daniels et al., Citation2023; Giovenco et al., Citation2021; Mannell et al., Citation2019). Obtaining a permission to use PrEP, from sexual partner was challenging in most cases. Many AGYW struggled to share PrEP use with their sexual partners for fears of reflecting an image of sexual misbehavior and infidelity. Findings from the current review came in accordance with Skovdal et al., in Zimbabwe, who reported that AGYW perceived seeking permission from sexual partner as practically difficult and potentially dangerous (Skovdal et al., Citation2022). Concealing the use of daily tablets was challenging for AGYW, especially in circumstances of poverty and lack of privacy.

Improving gender equality in sub-Saharan Africa is a longstanding challenge and the findings of the current review urge the need for women empowerment in decision making. It is crucial to escalate effective public communication about PrEP and normalize their use to help AGYW access the treatment to protect themselves against HIV. Intensive campaigns to dismantle misconceptions regarding the association of PrEP with unfaithfulness and promiscuity in sexual relations are vital. Teaching AGYW about the best disclosure strategies would help them be ready for sharing the information without implicating a dramatic reaction from sexual partners, family members, peers and the wider community. Agot et al., in Western Kenya, engaged uncooperative partners in support club to improve understanding of PrEP, and reported that information sessions helped changing the opinion of these partners (Agot et al., Citation2022). Similarly, interventions involving male sensitization sessions reported to have a positive effect in creating a supportive partner (Hartmann et al., Citation2021).

In the current review, AGYW perceived PrEP utilization as a proactive health habit that enabled them to take control on their sexual lives. Many AGYW felt that using PrEP was easier than negotiating a condom use with partner. In many sub-Saharan Africa settings, condom use reported to be very low despite the high rates of STI (Maticka-Tyndale, Citation2012).

Healthcare providers are key to the uptake and adherence of PrEP among AGYW. Experiences of AGYW, highlighted good quality of healthcare service related to PrEP in most programmes. AGYW valued the provision of adequate information in supporting their decision to enroll and persist. Moreover, the convenience of access to PrEP was highly appreciated by AGYW. Services such as text reminders and extending pill-refilling services to community setting were perceived to improve convenience (Barnabee et al., Citation2022). In general, results demonstrated that supportive healthcare providers improved AGYW experience and increased their adherence. On the contrary, unsupportive healthcare providers acted as a barrier to accessing PrEP. Research reported similar observation from healthcare providers (O'Malley et al., Citation2021; Skovdal et al., Citation2022). To avert negative attitudes from healthcare providers toward AGYW, special training on supporting this age category is essential.

The results of the current review outlined some negative experiences associated with PrEP pills. AGYW expressed preference for more discreet options like an injection. This would solve a few of their challenges including home storage, refusal from family and sexual partners and less frequent visits to the clinic (Irungu et al., Citation2021). A feminine appearance of the pills could improve the uptake and adherence (Maseko et al., Citation2020). Proper management of side-effects by adequate medical care, counseling and supportive treatment can improve the adherence among AGYW (Chebet et al., Citation2023; Duby et al., Citation2023; Jackson-Gibson et al., Citation2021).

Limitation

The wide range of PrEP initiatives in this context offers a breath of views around AGYW experiences and challenges related to this treatment. However, recruiting participants who were already been enrolled in different PrEP initiatives might not be reflective of AGYW in general. The purposive selection of study participants within the included studies might potentially be associated with bias to the generalizability of the findings. In sub-Saharan Africa, full autonomy of AGYW to voluntarily participate in studies is challenging. In the included qualitative studies, social desirability could have affected AGYW answers. Furthermore, interpretation of qualitative research findings could be associated with inaccuracies as different studies applied different approach to analysis.

Conclusion

The findings of the current review highlighted the detrimental effect of stigma about PrEP use on AGYW. It is essential to leverage the window of opportunity to alleviate the burden on AGYW in sub-Saharan Africa by intensive campaigns to normalize the use of PrEP. Widening the visibility of PrEP helps reducing stigma and enhances adherence. More research into enablers of AGYW to access and adhere to PrEP is essential.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agot, K., Hartmann, M., Otticha, S., Minnis, A., Onyango, J., Ochillo, M., & Roberts, S. T. (2022). “I didn’t support PrEP because I didn’t know what it was”: Inadequate information undermines male partner support for young women’s pre-exposure prophylaxis use in western Kenya. African Journal of AIDS Research: AJAR, 21(3), 221–230. https://doi.org/10.2989/16085906.2022.2049831

- Barnabee, G., O'Bryan, G., Ndeikemona, L., Billah, I., Silas, L., Morgan, K. L., Shulock, K., Mawire, S., MacLachlan, E., Nghipangelwa, J., Muremi, E., Ensminger, A., Forster, N., & O'Malley, G. (2022). Improving HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis persistence among adolescent girls and young women: Insights from a mixed-methods evaluation of community, hybrid, and facility service delivery models in Namibia. Frontiers in Reproductive Health, 4, 1048702. https://doi.org/10.3389/frph.2022.1048702

- Beesham, I., Dovel, K., Mashele, N., Bekker, L.-G., Gorbach, P., Coates, T. J., Myer, L., & Joseph Davey, D. L. (2022). Barriers to oral HIV pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) adherence among pregnant and post-partum women from Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS and Behavior, 26(9), 3079–3087. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-022-03652-2

- Bjertrup, P. J., Mmema, N., Dlamini, V., Ciglenecki, I., Mpala, Q., Matse, S., Kerschberger, B., & Wringe, A. (2021). PrEP reminds me that I am the one to take responsibility of my life: A qualitative study exploring experiences of and attitudes towards pre-exposure prophylaxis use by women in Eswatini. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 727. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10766-0

- Campbell, C., & Mannell, J. (2016). Conceptualising the agency of highly marginalised women: Intimate partner violence in extreme settings. Global Public Health, 11(1–2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2015.1109694

- Chabata, S. T., Hensen, B., Chiyaka, T., Mushati, P., Busza, J., Floyd, S., Birdthistle, I., Hargreaves, J. R., & Cowan, F. M. (2020). Condom use among young women who sell sex in Zimbabwe: A prevention cascade analysis to identify gaps in HIV prevention programming. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 23(Suppl 3), e25512. https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25512

- Chapman, J., do Nascimento, N., & Mandal, M. (2019). Role of male sex partners in HIV risk of adolescent girls and young women in Mozambique. Global Health: Science and Practice, 7(3), 435–446. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-19-00117

- Chebet, J. J., McMahon, S. A., Tarumbiswa, T., Hlalele, H., Maponga, C., Mandara, E., Ernst, K., Alaofe, H., Baernighausen, T., Ehiri, J. E., Geldsetzer, P., & Nichter, M. (2023). Motivations for pre-exposure prophylaxis uptake and decline in an HIV-hyperendemic setting: Findings from a qualitative implementation study in Lesotho. AIDS Research and Therapy, 20(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12981-023-00535-x

- Crowley, K., Dugas, M., Gao, G., Burn, L., Igumbor, K., Njapha, D., Piper, J., Veronese, F., & Agarwal, R. (2022). Market segmentation of South African adolescent girls and young women to inform HIV prevention product marketing strategy: A mixed methods study. Health Marketing Quarterly, 39(2), 159–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/07359683.2021.2007587

- Daniels, J., De Vos, L., Bezuidenhout, D., Atujuna, M., Celum, C., Hosek, S., Bekker, L.-G., & Medina-Marino, A. (2023). “I know why I am taking this pill”: Young women navigation of disclosure and support for PrEP uptake and adherence in Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. PLOS Global Public Health, 3(1), e0000636. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000636

- Duby, Z., Bunce, B., Fowler, C., Jonas, K., Bergh, K., Govindasamy, D., Wagner, C., & Mathews, C. (2023). “These girls have a chance to be the future generation of HIV negative”: Experiences of implementing a PrEP programme for adolescent girls and young women in South Africa. AIDS and Behavior, 27(1), 134–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-022-03750-1

- Duby, Z., Jonas, K., McClinton Appollis, T., Maruping, K., Dietrich, J., & Mathews, C. (2021). “Condoms are boring”: Navigating relationship dynamics, gendered power, and motivations for condomless sex amongst adolescents and young people in South Africa. International Journal of Sexual Health, 33(1), 40–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317611.2020.1851334

- Giovenco, D., Gill, K., Fynn, L., Duyver, M., O'Rourke, S., van der Straten, A., Morton, J. F., Celum, C. L., & Bekker, L.-G. (2021). Experiences of oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use disclosure among South African adolescent girls and young women and its perceived impact on adherence. PloS One, 16(3), e0248307. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248307

- Grant, R. M., Lama, J. R., Anderson, P. L., McMahan, V., Liu, A. Y., Vargas, L., Goicochea, P., Casapía, M., Guanira-Carranza, J. V., Ramirez-Cardich, M. E., Montoya-Herrera, O., Fernández, T., Veloso, V. G., Buchbinder, S. P., Chariyalertsak, S., Schechter, M., Bekker, L.-G., Mayer, K. H., Kallás, E. G., … Glidden, D. V. (2010). Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. The New England Journal of Medicine, 363(27), 2587–2599. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1011205

- Haribhai, S., Khadka, N., Mvududu, R., Mashele, N., Bekker, L.-G., Gorbach, P., Coates, T. J., Myer, L., & Joseph Davey, D. L. (2023). Psychosocial determinants of pre-exposure prophylaxis use among pregnant adolescent girls and young women in Cape Town, South Africa: A qualitative study. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 34(8), 548–556. https://doi.org/10.1177/09564624231152776

- Hartmann, M., Otticha, S., Agot, K., Minnis, A. M., Montgomery, E. T., & Roberts, S. T. (2021). Tu’Washindi na PrEP: Working with young women and service providers to design an intervention for PREP uptake and adherence in the context of gender-based violence. AIDS Education and Prevention: Official Publication of the International Society for AIDS Education, 33(2), 103–119. https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2021.33.2.103

- Irungu, E. M., & Baeten, J. M. (2020). PrEP rollout in Africa: Status and opportunity. Nature Medicine, 26(5), 655–664. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0872-x

- Irungu, E., Khoza, N., & Velloza, J. (2021). Multi-level interventions to promote oral pre-exposure prophylaxis use among adolescent girls and young women: A review of recent research. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 18(6), 490–499. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-021-00576-9

- Jackson-Gibson, M., Ezema, A. U., Orero, W., Were, I., Ohiomoba, R. O., Mbullo, P. O., & Hirschhorn, L. R. (2021). Facilitators and barriers to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) uptake through a community-based intervention strategy among adolescent girls and young women in Seme Sub-County, Kisumu, Kenya. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1284. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11335-1

- Jani, N., Mathur, S., Kahabuka, C., Makyao, N., & Pilgrim, N. (2021). Relationship dynamics and anticipated stigma: Key considerations for PrEP use among Tanzanian adolescent girls and young women and male partners. PloS One, 16(2), e0246717. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246717

- Kayesu, I., Mayanja, Y., Nakirijja, C., Machira, Y. W., Price, M., Seeley, J., & Siu, G. (2022). Uptake of and adherence to oral pre-exposure prophylaxis among adolescent girls and young women at high risk of HIV-infection in Kampala, Uganda: A qualitative study of experiences, facilitators and barriers. BMC Women’s Health, 22(1), 440. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-02018-z

- Long, H. A., French, D. P., & Brooks, J. M. (2020). Optimising the value of the critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) tool for quality appraisal in qualitative evidence synthesis. Research Methods in Medicine & Health Sciences, 1(1), 31–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/2632084320947559

- Mannell, J., Willan, S., Shahmanesh, M., Seeley, J., Sherr, L., & Gibbs, A. (2019). Why interventions to prevent intimate partner violence and HIV have failed young women in southern Africa. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 22(8), e25380. https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25380

- Maseko, B., Hill, L. M., Phanga, T., Bhushan, N., Vansia, D., Kamtsendero, L., Pettifor, A. E., Bekker, L.-G., Hosseinipour, M. C., & Rosenberg, N. E. (2020). Perceptions of and interest in HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis use among adolescent girls and young women in Lilongwe, Malawi. PloS One, 15(1), e0226062. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0226062

- Maticka-Tyndale, E. (2012). Condoms in sub-Saharan Africa. Sexual Health, 9(1), 59–72. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH11033

- Murewanhema, G., Musuka, G., Moyo, P., Moyo, E., & Dzinamarira, T. (2022). HIV and adolescent girls and young women in Sub‐Saharan Africa: A call for expedited action to reduce new infections. IJID Regions, 5, 30–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijregi.2022.08.009

- Ninsiima, A. B., Leye, E., Michielsen, K., Kemigisha, E., Nyakato, V. N., & Coene, G. (2018). “Girls have more challenges; they need to be locked up”: A qualitative study of gender norms and the sexuality of young adolescents in Uganda. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(2), 193. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15020193

- O’Rourke, S., Hartmann, M., Myers, L., Lawrence, N., Gill, K., Morton, J. F., Celum, C. L., Bekker, L.-G., & van der Straten, A. (2021). The PrEP journey: Understanding how internal drivers and external circumstances impact the PrEP trajectory of adolescent girls and young women in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS and Behavior, 25(7), 2154–2165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-03145-0

- Ojeda, V. D., Amico, K. R., Hughes, J. P., Wilson, E., Li, M., Holtz, T. H., Chitwarakorn, A., Grant, R. M., Dye, B. J., Bekker, L.-G., Mannheimer, S., Marzinke, M., & Hendrix, C. W. (2019). Low Disclosure of PrEP nonadherence and HIV risk behaviors associated with poor HIV PrEP adherence in the HPTN 067/ADAPT study. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999), 82(1), 34–40. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000002103

- O'Malley, G., Beima-Sofie, K. M., Roche, S. D., Rousseau, E., Travill, D., Omollo, V., Delany-Moretlwe, S., Bekker, L.-G., Bukusi, E. A., Kinuthia, J., Barnabee, G., Dettinger, J. C., Wagner, A. D., Pintye, J., Morton, J. F., Johnson, R. E., Baeten, J. M., John-Stewart, G., & Celum, C. L. (2021). Health care providers as agents of change: Integrating PrEP with other sexual and reproductive health services for adolescent girls and young women. Frontiers in Reproductive Health, 3, 668672. https://doi.org/10.3389/frph.2021.668672

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. International Journal of Surgery (London, England), 88, 105906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906

- Patel, P., Sato, K., Bhandari, N., Kanagasabai, U., Schelar, E., Cooney, C., Eakle, R., Klucking, S., Toiv, N., & Saul, J. (2022). From policy to practice: Uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis among adolescent girls and young women in United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief-supported countries, 2017–2020. AIDS (London, England), 36(Suppl 1), S15–S26. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000003103

- Pintye, J., O'Malley, G., Kinuthia, J., Abuna, F., Escudero, J. N., Mugambi, M., Awuor, M., Dollah, A., Dettinger, J. C., Kohler, P., John-Stewart, G., & Beima-Sofie, K. (2021). Influences on early discontinuation and persistence of daily oral PrEP use among Kenyan adolescent girls and young women: A qualitative evaluation from a PrEP implementation program. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999), 86(4), e83–e89. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000002587

- PrEPWatch. (2023). AVAC global PrEP tracker. AVAC. Retrieved August, from https://www.prepwatch.org/country-updates/

- Rousseau, E., Katz, A. W. K., O'Rourke, S., Bekker, L.-G., Delany-Moretlwe, S., Bukusi, E., Travill, D., Omollo, V., Morton, J. F., O'Malley, G., Haberer, J. E., Heffron, R., Johnson, R., Celum, C., Baeten, J. M., & van der Straten, A. (2021). Adolescent girls and young women’s PrEP-user journey during an implementation science study in South Africa and Kenya. PloS One, 16(10), e0258542. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258542

- Sidebottom, D., Ekström, A. M., & Strömdahl, S. (2018). A systematic review of adherence to oral pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV–how can we improve uptake and adherence? BMC Infectious Diseases, 18(1), 581. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3463-4

- Skovdal, M., Clausen, C. L., Magoge-Mandizvidza, P., Dzamatira, F., Maswera, R., Nyamwanza, R. P., Nyamukapa, C., Thomas, R., & Gregson, S. (2022). How gender norms and ‘good girl’notions prevent adolescent girls and young women from engaging with PrEP: Qualitative insights from Zimbabwe. BMC Women’s Health, 22(1), 344. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01928-2

- Smith, D. K., Thigpen, M. C., Nesheim, S. R., Lampe, M. A., Paxton, L. A., Samandari, T., Lansky, A., Mermin, J., & Fenton, K. A. (2012). Interim guidance for clinicians considering the use of preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in heterosexually active adults. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 61(31), 586–589.

- Tailor, J., Rodrigues, J., Meade, J., Segal, K., & Benjamin Mwakyosi, L. (2022). Correlations between oral Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) initiations and policies that enable the use of PrEP to address HIV globally. PLOS Global Public Health, 2(12), e0001202. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001202

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2012). FDA approves first drug for reducing the risk of sexually acquired HIV infection.

- UNAIDS. (2023). The path that ends AIDS: UNAIDS Global AIDS Update 2023 (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.). https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2023-unaids-global-aids-update_en.pdf

- Vasco, E., & Crowley, T. (2022). Young women’s lived experiences of using PrEP in Namibia: A qualitative phenomenological study. International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences, 17, 100481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijans.2022.100481

- Velloza, J., Khoza, N., Scorgie, F., Chitukuta, M., Mutero, P., Mutiti, K., Mangxilana, N., Nobula, L., Bulterys, M. A., Atujuna, M., Hosek, S., Heffron, R., Bekker, L.-G., Mgodi, N., Chirenje, M., Celum, C., & Delany-Moretlwe, S. (2020). The influence of HIV‐related stigma on PrEP disclosure and adherence among adolescent girls and young women in HPTN 082: A qualitative study. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 23(3), e25463. https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25463

- Were, D., Musau, A., Mutegi, J., Ongwen, P., Manguro, G., Kamau, M., Marwa, T., Gwaro, H., Mukui, I., Plotkin, M., & Reed, J. (2020). Using a HIV prevention cascade for identifying missed opportunities in PrEP delivery in Kenya: Results from a programmatic surveillance study. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 23(Suppl 3), e25537. https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25537

- World Health Organization. (2012). Guidance on pre-exposure oral prophylaxis (PrEP) for serodiscordant couples, men who have sex with men and transgender women at high risk of HIV in implementation research, Annexes.

- World Health Organization. (2015). Policy brief: Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP): WHO expands recommendation on oral pre-exposure prophylaxis of HIV infection (PrEP).