ABSTRACT

A 65-year-old Caucasian female presented with abdominal symptoms and obstructive jaundice. She reported a significant pancreatic cancer history in her family. Her CT of the abdomen and pelvis showed 3.9 × 3.5 cm centrally necrotic mass within the pancreatic head, occluding the superior mesenteric and splenic veins; peripancreatic lymph nodes were enlarged, and there were many hepatic lesions. She underwent biopsy of the hepatic lesions showing metastatic tumor cells, arranged in the form of nests, with enlarged and hyperchromatic irregular nuclei with some nucleoli and moderate eosinophilic cytoplasm. Immunohistochemical staining on cancer cells was positive for CK7, P40, GATA3. These findings were concerning for poorly differentiated metastatic squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). PET-CT showed no other hypermetabolic lesions, suggestive of another primary except pancreatic head with SUV of 17.8, hepatic metastasis and 1 cm right retroperitoneal lymph node. The patient was diagnosed with metastatic SCC of the pancreas. Contrary to the well-known genetic mutations of pancreatic adenocarcinoma, the data on pancreatic SCC-related mutations is limited; however, one such mutation is BRCA-2 exon 15 germline mutation reported in a locally advanced SCC of the pancreas. The index patient is one of those rare cases in which a significant family history of pancreatic cancer was reported. We believe that some familial mutation could be responsible for this finding, i.e., occurrence of pancreatic cancer in multiple family members. Further research is necessary to explore such association.

Introduction

Pancreatic neoplasm is the fourth commonest gastrointestinal (GI) malignancies in the United States. Among several types of pancreatic neoplasms, adenocarcinoma (ADC) of the pancreas is the commonest subtype. Other less common subtypes of pancreatic neoplasms include endocrine tumors, cystic neoplasms of the pancreas, intraductal papillary mucinous tumors, solid pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas, acinar cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the pancreas, adenosquamous carcinoma (ASC), primary lymphoma of the pancreas and metastatic lesions of the pancreas.Citation1 Of these uncommon subtypes, pancreatic SCC is of scarce variety, accounted for an incidence of 0.5 to 2% of all cases of pancreatic cancers.Citation2–Citation4 Though this histologic subtype is exceptionally uncommon, there has been a publication of sporadic case reports on this rare entity.Citation4–Citation6 To our knowledge, the occurrence of this rare subtype creates a diagnostic dilemma due to its rareness, and therefore, warrants an adequate literature search. Therefore, we present a rare case of pancreatic SCC. This article focuses on its presentation, pathogenesis, diagnosis and management, and provides a comprehensive but relevant overview of the previous literature.

Case report

A 65-year-old Caucasian female without significant medical history presented to the emergency department (ED) with a one-month history of anorexia, weight loss, generalized abdominal pain and back pain. The pain had a poor response to over the counter analgesics and was of progressive and continuous nature. Few days before her ED visit, she started noticing yellowish discoloration of skin in addition to dark yellow colored urine and pale colored stools. Her other symptoms included frequent abdominal bloating and belching. She denied nausea, vomiting, changes in urinary/bowel habits, confusion, hematemesis and melena. She denied a history of travel, hepatitis, pancreatitis, or drug abuse. She had a ten pack-year smoking history but quit 35 years ago. She denied alcohol use. Her family history was significant for malignancy; mother and a maternal uncle had pancreatic cancer while father had lung cancer. On arrival, her vitals were stable. She appeared pale on examination but no distress. Sclera was icteric. Oral cavity was moist without lesions. Head and neck exam showed no thyromegaly or lymphadenopathy. Cardiopulmonary examination was unremarkable. Abdomen was non-tender without organomegaly or palpable masses. Extremities were negative for pedal edema or asterixis. Laboratory data was positive for mild normocytic, normochromic anemia (Hemoglobin-11.8 mg/dl, range:12–15.7), hyperbilirubinemia (Total bilirubin: 5.6 mg/dl, range: 0.2–1.3; direct bilirubin: 3 mg/dl, range; 0.0–0.3) and mildly elevated liver enzymes (AST:129 U/L, range:8–40; ALT:200 U/L, range:7–56; ALP:266 U/L, 39–117). Ultrasonography of the abdomen showed cholelithiasis, dilatation of common bile duct (CBD), multiple hypoechoic masses of the liver and mass in the head of the pancreas measuring up to 4.2 cm in maximum dimension. For possible pancreatic malignancy, she underwent CT scan of abdomen and pelvis with pancreatic protocol which confirmed 3.9 × 3.5 cm centrally necrotic mass within the pancreatic head, occluding the superior mesenteric and splenic veins (). Peripancreatic lymph nodes were also enlarged. CBD and pancreatic ducts both were dilated, and there were multiple hepatic lesions of metastatic nature involving segments II to VIII. The largest hepatic lesion was 3.3 × 3 cm present in segment VII. Tumor markers including carcinoembryonic agent (75.6 ng/ml, range:0.0–4.9), cancer antigen 125 (436.9 U/ml, range:0.0–30.1) and carbohydrate 19.9 (390.8 U/ml, range: 0.0–34.9) were elevated.

Figure 1. CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis showing large mass in the head of pancreas with multiple hypodense lesions in the liver in (a) axial view and (b) coronal view (arrows).

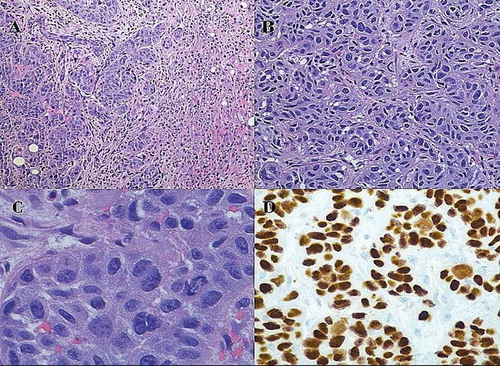

The patient was admitted for cholestatic jaundice due to obstruction of biliary tree from cancer involving the head of the pancreas. She had distal segmental stenosis of CBD on endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for which sphincterotomy and biliary stent placement was performed. She underwent laparoscopy with laparoscopic ultrasound for evaluation of the pancreatic and liver masses and tissue biopsy. Intraoperative findings included a 4-cm mass in the head of the pancreas and multiple hepatic masses. Multiple biopsies were obtained from lesions in segment III and segment V. No mass was noted in the small and large bowel, ovaries or any other intraabdominal organ. The patient tolerated the procedure well and required oral narcotics for pain control. She was discharged home in stable condition. The plan was to follow-up on outpatient with pathology results. Though the patient was thought to be a case of pancreatic ADC on a preliminary assessment, the histopathology of liver biopsy was suggestive of pancreatic SCC ().

Figure 2. Histochemical findings of metastatic lesions of the liver: (a) low power view (H and E stain, original magnification of 100X) of showing tumor clusters on the left and hepatic tissue on the right with no evidence of glandular differentiation (b) high power view (H and E stain, original magnification of 400x) showing nests of tumor cells. (c) very high-power view (H and E stain, original magnification of 600x) showing tumor cells with intercellular bridges (a sign of squamous differentiation), variably sized hyperchromatic nuclei and small nucleoli. (d) high power view (Immunohistochemical staining, original magnification of 400x) showing positive nuclear staining with p40 showing squamous differentiation.

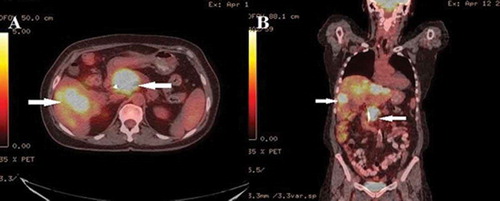

Biopsy specimens showed metastatic tumor cells with enlarged and hyperchromatic irregular nuclei with some nucleoli and moderate eosinophilic cytoplasm. The tumor cells were arranged in the form of nests. Immunohistochemical staining on cancer cells was positive for CK7, P40, GATA3 (patchy pattern). Staining with CK20, HAS, glypican-3, vimentin, BRST1, CDX2 and TTF1 was negative. The PET-CT showed no other hypermetabolic lesions except pancreatic head with SUV of 17.8, hepatic metastasis and 1 cm right retroperitoneal lymph node ().

Figure 3. PET-CT scan showing large hypermetabolic lesion in the head of pancreas, multiple hypermetabolic hepatic lesions and one hypermetabolic right retroperitoneal lymph node in (a) axial view and (b) coronal view (arrows).

Based on biopsy results, intraoperative findings and PET-CT report, a diagnosis of stage IV (T2, N0, M1, G3) poorly differentiated pancreatic SCC with hepatic metastases was made. Palliative chemotherapy with protein-bound paclitaxel and gemcitabine was recommended. However, given the patient’s experience of her mother’s prognosis, she declined palliative chemotherapy and opted for hospice care. She presented with gastric outlet obstruction three months following diagnosis and underwent decompressive percutaneous gastrostomy tube for symptomatic relief.

Discussion

The pancreas contains dual-function structure with both endocrine (islet of Langerhans) and exocrine (ducts, acini, connective tissue) elements. Among exocrine pancreatic cancers, both pancreatic ADC and SCC arise from the ductal tissue. Furthermore, both subtypes coexisting in the form of ASC has been reported.Citation7 As the normal pancreatic tissue contains no squamous cells in a non-diseased state, the primary pancreatic SCC has been postulated to develop because of many reasons. One such mechanism includes the squamous metaplasia of ductules of the pancreas in the presence of chronic inflammation, causing the origination of SCC via tissue differentiation.Citation8 The evidence of squamous metaplasia as a common finding among patients with chronic pancreatitis also favors this theory.Citation9 On the other hand, though the squamous cell metaplasia is relatively commonly seen, pancreatic SCC has been uncommonly reported. This means there could be a potential role of other Pathogenic Factors for this cancer subtype or more than one mechanisms are possible. Therefore, proposed mechanisms for the development of this entity include 1) malignant differentiation of multipotent stem cells to SCC, 2) malignant transformation of aberrant or ectopic squamous cells to SCC 3) transdifferentiation of pre-existing ADC to SCC and 4) collision tumor theory.Citation8

Pancreatic SCC has also been speculated as a variant of pancreatic ASC in which the glandular component of cancer has disappeared whereas the squamous component has persisted.Citation10 ASC subtype, though rarer than pancreatic ADC, is relatively common than SCC variety. It is critically important to exclude SCC from primaries located in other organs before the diagnosis of primary pancreatic SCC can be been made. In any given case of pancreatic SCC, the odds of this lesion being from organs other than pancreas is many folds when compared with the odds of this lesion being from a primary SCC originating in the pancreas itself. SCC, metastatic to the pancreas, could arise from head and neck, lung, cervix or esophagus.

Regarding the anatomic location of pancreatic SCC, one study reported more than 50% cases in the head region followed by 21.6% cases in the tail of the pancreas, 19.5% cases in multiple locations and 5.9% cases in the body of the pancreas.Citation11 Though the conventional risk factors for pancreatic ADC have been reported in pancreatic SCC patients as well, no specific risk factors for the development of SCC have been established. Among them, chronic pancreatitis has been speculated as a risk factor for SCC as it has been reported to coexist in many biopsy specimens of SCC. Contrary to the well-known genetic mutations of pancreatic ADC, the data on pancreatic SCC-related mutations is limited.Citation12 One such example includes BRCA-2 exon 15 germline mutation in a patient with locally advanced pancreatic SCC reported by Schultheis et al.Citation13 BRCA-2 germline mutation was detected in her case given ovarian and breast cancer history in her first-degree relatives. The patient had no other cancers at the time of presentation except pancreatic SCC. This example means there could be a potential role of familial or inherited mutations in pathogenesis of pancreatic SCC. Beyond the aforementioned case, family history of pancreatic cancer has rarely been reported.Citation11

The index patient is one of those rare cases in which a significant family history of pancreatic cancer was identified. Our limitation, however, is the unavailability of pathologic reports in deceased family members. BRCA-2 germline mutation was not tested in our patient as it was not clinically warranted. Furthermore, it had no impact on patient’s medical management.

The presentation of pancreatic SCC is no different from pancreatic ADC. Mean age of presentation is 61.9 years with predominant involvement being in males.Citation11 In the literature, commonly reported symptoms include anorexia, weight loss, abdominal pain and back pain.Citation4 Based on anatomic location, obstructive jaundice or gastric outlet obstruction could also be other presenting features.Citation14 Uncommon presentation includes fever, fatigue, epigastric mass, hyperglycemia or diabetes. Rarely, pancreatic SCC has presented with upper GI bleeding (acute anemia, hematemesis or melena) due to local invasion into stomach or duodenum.Citation15,Citation16 The current patient presented with vague GI symptoms and obstructive jaundice.

No specific blood tests are available to detect pancreatic SCC. Erica et al. have reported leukemoid reaction in pancreatic SCC as a paraneoplastic syndrome.Citation14 However, like pancreatic ADC, tumor markers (CA-19.9 and CEA) can aid in diagnosis. Less commonly, SCC antigen has been reported to monitor response to the treatment or for the detection of recurrence of treatment.Citation16 Hypercalcemia can concomitantly exist with SCC. Pancreatic imaging, especially CT scan, has a tremendous role in diagnosis or staging. On CT with contrast, pancreatic SCC might exhibit two features different from pancreatic ADC because of hypervascularity of SCC; these include 1) contrast enhancement of tumor and 2) angiographic blush pattern.Citation8 The role of PET/CT could be the detection of metastases and exclusion of another primary site. Tissue diagnosis via histology and immunostaining can be achieved with CT-guided biopsy, EUS-FNA, FNA-core needle biopsy or laparoscopic biopsy. Pancreatic SCC is usually advanced at the time of presentation. Therefore, the curative resection is possible only in less than one-third of patients.Citation11 On the other hand, palliative chemotherapy, radiotherapy or their combination is used in most of the non-resectable diseases. Pancreatic SCC is more aggressive than pancreatic ADC and has a poorer prognosis.Citation17 The survival is significantly better in cases with curative resection than cases with no resection (Median overall survival of 10 months versus 4 months respectively).Citation11 The index patient had a non-resectable disease and therefore poor prognosis at the time of diagnosis. She opted for no therapy, and therefore, ended up with gastric outlet obstruction. This implies a grave prognosis.

Conclusion

Pancreatic SSC, though rare, could occur. The accurate diagnosis requires ruling out of other SCC primaries. Overall prognosis is poor in cases which are not resectable. A familial mutation could be responsible for the occurrence of pancreatic cancer in multiple family members. Further research is necessary to establish a mutational etiology in cases with suspected familial cases.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgements

None

Additional information

Funding

References

- Mulkeen AL, Yoo PS, Cha C. Less common neoplasms of the pancreas. W J Gastroenterol: WJG. 2006 May 28;12(20):3180. doi:10.3748/wjg.v12.i20.3180.

- Baylor SM, Berg JW. Cross‐classification and survival characteristics of 5,000 cases of cancer of the pancreas. J Surg Oncol. 1973 Jan 1;5(4):335–358.

- Miller JR, Baggenstoss AH, Comfort MW. Carcinoma of the pancreas. Effect of histological type and grade of malignancy on its behavior. Cancer. 1951 Mar;4(2):233–241.

- Brown HA, Dotto J, Robert M, Salem RR. Squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005 Nov 1;39(10):915–919.

- Alajlan BA, Bernadt CT, Kushnir VM. Primary squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas: a case report and literature review. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2017 Jun;29:1–4.

- Thomas D, Shah N, Shaaban H, Maroules M. An interesting clinical entity of squamous cell cancer of the pancreas with liver and bone metastases: a case report and review of the literature. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2014 Dec 1;45(1):88–90. doi:10.1007/s12029-013-9560-0.

- Borazanci E, Millis SZ, Korn R, Han H, Whatcott CJ, Gatalica Z, Barrett MT, Cridebring D, Von Hoff DD. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the pancreas: molecular characterization of 23 patients along with a literature review. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2015 Sep 15;7(9):132. doi:10.4251/wjgo.v7.i9.132.

- Al-Shehri A, Silverman S, Km K. Squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas. Curr Oncology. 2008 Dec;15(6):293.

- Layfield LJ, Cramer H, Madden J, Gopez EV, Liu K. Atypical squamous epithelium in cytologic specimens from the pancreas: cytological differential diagnosis and clinical implications. Diagn Cytopathol. 2001 Jul 1;25(1):38–42.

- Bralet MP, Terris B, Brégeaud L, Ruszniewski P, Bernades P, Belghiti J, Fléjou JF. Squamous cell carcinoma and lipomatous pseudohypertrophy of the pancreas. Virchows Archiv. 1999 Jun 1;434(6):569–572.

- Ntanasis-Stathopoulos I, Tsilimigras DI, Georgiadou D, Kanavidis P, Riccioni O, Salla C, Psaltopoulou T, Sergentanis TN. Squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas: a systematic review and pooled survival analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2017 Jul;1(79):193–204. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2017.04.006.

- Notta F, Hahn SA, Real FX. A genetic roadmap of pancreatic cancer: still evolving.. Gut. 2017 Oct 9;gutjnl-2016:2170-2178.

- Schultheis AM, Nguyen GP, Ortmann M, Kruis W, Büttner R, Schildhaus HU, Markiefka B. Squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas in a patient with germline BRCA2 mutation-response to neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy. Case Rep Oncol Med. 2014;2014:1–5. doi:10.1155/2014/860532.

- Lin E, Veeramachaneni H, Addissie B, Arora A. squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas. Am J Med Sci. 2018 Jan 1;355(1):94–96. doi:10.1016/j.amjms.2017.01.014.

- Petrucciani N, Pulcini F, Nigri GR, Ramacciato G. Squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas presenting with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Am Surg. 2012 May 1;78(5):E284.

- Minami T, Fukui K, Morita Y, Kondo S, Ohmori Y, Kanayama S, Taenaka N, Yoshikawa K, Tsujimura T. A case of squamous cell carcinoma of the pancreas with an initial symptom of tarry stool. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001 Sep;16(9):1077–1079.

- Makarova-Rusher OV, Ulahannan S, Greten TF, Duffy A. Pancreatic squamous cell carcinoma: a population-based study of epidemiology, clinicopathologic characteristics and outcomes. Pancreas. 2016 Nov;45(10):1432. doi:10.1097/MPA.0000000000000658.