ABSTRACT

Giant cell hepatitis (GCH) is a rare diagnosis in adults that is found in 0.25% of liver biopsies. GCH has been associated with multiple causes including drugs (6-mercaptopurine, methotrexate), toxins, viruses and autoimmune. GCH has been described in few patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Here we describe three patients diagnosed with GCH thought to be related to underlying CLL and its management. All of our patients were treated with a combination of immunosuppression as well as CLL-directed therapy to address CLL and concomitant liver disease. GCH is a rare manifestation of active CLL and should be ruled out with prompt liver biopsy in patients with CLL with persistent transaminitis without another attributable cause. Prompt treatment of GCH with immunosuppression is required to prevent long-term liver toxicity. If transaminitis does not improve with immunosuppression alone, the addition of CLL directed therapy should be considered in patients who carry this diagnosis to prevent long-term liver toxicity.

Introduction

Giant cell hepatitis (GCH) is a rare diagnosis in adults, found in approximately 0.25% of liver biopsies.Citation1 Histopathologically, it is characterized by the presence of multinucleated cells in the liver as a result of nonspecific tissue reaction to a number of different stimuli.Citation2 In adults, it can progress quickly from acute hepatitis to cirrhosis and can lead to hepatic failure and death. The exact pathogenesis remains unknown, but it is speculated to be due to hepatocyte nuclear proliferation without associated cell division.Citation2,Citation3 Previously described causes include exposure to drugs such as methotrexate, 6-mercaptopurine, and amitriptyline, toxins, viruses, and autoimmune hepatitis.Citation1,Citation2,Citation4-Citation8 Recently, there have been four individual case reports of GCH associated with chronic lymphocytic leukemia.Citation9-Citation12 Here, we describe three cases of GCH attributed to CLL treated at a single institution to attain oncologic and hepatic disease control.

Table 1. Summary of liver-specific laboratory testing performed for each patient including infectious and autoimmune causes of liver disease.

Case 1

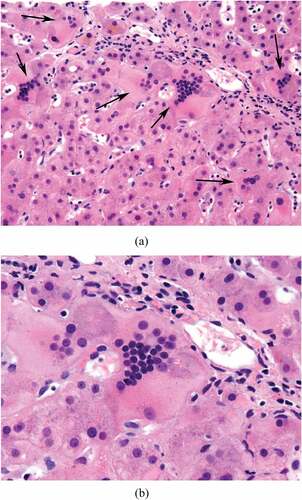

Case 1 is a 75-year-old female previously diagnosed with Rai Stage I CLL in 2013 which harbored deletion 11q and ATM deletion by next-generation sequencing (NGS). She was under active observation for two years when she developed grade 3 transaminitis with ALT 340 U/L and AST 283 U/L. At the time, she was taking 12 mg methotrexate weekly for rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and her transaminitis was attributed to methotrexate and statin use. Her statin was discontinued. Her methotrexate dose was increased to 20 mg once per week to control her RA. Approximately 1 month later, she developed CTCAE grade 4 transaminitis (ALT 2158 U/L and AST 1329 U/L) with grade 1 elevated bilirubin (2.0 mg/dL). She underwent CT imaging which demonstrated bulky mesenteric adenopathy and enlarged porta hepatis lymphadenopathy. Her transaminitis was presumed to be related to a combination of methotrexate therapy and CLL liver infiltration. Liver biopsy was deferred, methotrexate was discontinued, and she was initiated on 40 mg prednisone daily, which was increased to 100 mg daily. One week later, her transaminitis improved to grade 1 (ALT 254 U/L and ALT 68 U/L) and rituximab 500 mg/m2 for four weekly doses was added for treatment of CLL. Her AST and ALT improved but remained elevated at 2–5x the upper limit of normal despite treatment with rituximab/prednisone and cessation of methotrexate. Further workup was negative for cytolomegavirus (CMV), Epstein Barr virus (EBV), hepatitis B, C, and E. Her anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) was positive 1:1280 with diffuse pattern that was attributed to underling RA (CitationTable 1). Autoimmune serologies including Liver Kidney Microsomal (LKM) antibody, anti-smooth muscle antibody, SLA antibody, and anti-mitochondrial were negative. She underwent transjugular core liver biopsy for persistent liver transaminitis that demonstrated lymphocyte infiltration consistent with involvement by CLL, cholestasis with syncytial giant cell hepatocyte formation with giant cell hepatitis pattern of injury, mild portal perivenular and space of disease fibrosis and mild hemophagocytosis (). There was no evidence of viral inclusions. She was next treated with 600 mg/m2 cyclophosphamide every 3 weeks with rituximab 375 mg/m2. She initiated ibrutinib at a dose of 280 mg daily for treatment of her CLL concurrently with cyclophosphamide/rituximab. Her liver function normalized after two cycles of cyclophosphamide/rituximab and ibrutinib. Prednisone was tapered, and azathioprine 50 mg daily was added as a steroid-sparing agent to treat GCH. Her liver function has remained normal for >3 years since her diagnosis.

Case 2

Case 2 is a 66-year-old male diagnosed with Rai Stage 0 CLL in 2010. He was noted to have deletion 11q by fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH) without deletion 17p or TP53 mutation. He was under active observation for 5 years when he ultimately required treatment for increasing lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, and new ascites. His AST and ALT were elevated for 5 months prior to biopsy (peak 145 U/L and 468 U/L, respectively). He underwent a laparoscopic liver biopsy that demonstrated massive portal infiltration with small mature CD5+, CD10- CD23+, CD20 + B cell consistent with involvement with CLL. A peritoneal drain was placed for management of malignant ascites. PET/CT demonstrated significant adenopathy without significant FDG-avidity consistent with CLL without evidence of transformed disease. He initiated CLL-directed therapy with bendamustine and rituximab and received three cycles with improvement in adenopathy and lymphocytosis but persistent ascites. His AST and ALT also normalized. Hepatitis A, B,and C serologies were negative. Right upper quadrant sonogram did not demonstrate portal or hepatic vein thrombosis. ANA, anti-mitochondrial antibody and anti-smooth muscle antibody were also negative. Alpha-1 anti-trypsin levels were within normal limits. In the setting of persistent ascites, a transjugular liver biopsy was performed which demonstrated giant cell hepatitis with cirrhosis without evidence of CLL infiltration. He was treated with 60 mg prednisone with improvement of his ascites. He started the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody ofatumumab on a maintenance scheduleCitation13 for treatment of CLL with IVIG for hypogammaglobulinemia. His ascites continued to improve. Azathioprine was added to allow for slow prednisone taper over 5 months. Azathioprine was well tolerated and he continued without evidence of recurrent GCH for >2 years.

Case 3

Case 3 is a 58-year-old male diagnosed with Rai Stage 0 CLL with deletion 11q and deletion 13q present at diagnosis and a NOTCH1 mutation by NGS. He was followed for a year when he was noted to have anemia with elevated LDH, undetectable haptoglobin and positive DAT consistent with autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA). His AST was 159 U/L (grade1), ALT 383 U/L (grade 2), and bilirubin was 1.6. (grade 1). Hepatitis B and C serologies were negative, and blood quantitative CMV PCR was negative. His AIHA was treated with prednisone 50 mg daily, rituximab 375 mg/m2 weekly and supportive red blood cell transfusions. Transjugular liver biopsy was performed prior to starting rituximab for transaminitis that demonstrated chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma involving liver with associated giant cell hepatitis, with moderate periportal fibrosis including septae formation. His AST and ALT partially improved (45 U/L and 147 U/L) with rituximab/prednisone and then 420 mg of ibrutinib was added 4 weeks after initiating treatment. Subsequently, his AST/ALT increased (73 U/L and 330 U/L) and he was evaluated by hepatology. Workup for infectious causes, including CMV, EBV and hepatitis E, and autoimmune hepatitis was negative. He had a normal alpha-1 antitrypsin level. Right upper quadrant sonogram did not reveal hepatic or portal vein thrombosis. Prednisone 40 mg was continued, and he started azathioprine for presumed GCH flare with improvement in his transaminases (AST 31 U/L ALT 50 U/L). His azathioprine was increased to 100 mg daily as prednisone was tapered without further flare of his transaminitis. IVIG was initiated two months after start azathioprine for management of hypogammaglobulinemia. At >2 years of follow up, his CLL remains under control and he has not had a flare of his GCH.

Discussion

GCH is a rare, but clinically significant diagnosis which can present as fulminant hepatitis.Citation14 Four cases of GCH associated with CLL have previously been reported. The first case, reported by Fimmel et al., was diagnosed in a patient with CLL and concomitant paramyxo-like virus. The patient’s GCH resolved spontaneously though he ultimately developed cirrhosis.Citation9 A second case, reported by Alexopolou et al., a patient with CLL was admitted for acute liver failure and was treated for presumed EBV reactivation. On post-mortem examination, the patient was subsequently found to have GCH.Citation10 Neither patient was receiving active treatment for CLL at the time of diagnosis. In a third case reported by Gupta et al., biopsy-proven GCH was diagnosed in a patient with CLL who was receiving treatment with chlorambucil, rituximab and prednisone. She was treated with hydrocortisone and intravenous immunoglobulin with resolution of her transaminitis and symptoms.Citation11 The most recent case reported by Gupta et al., GCH was diagnosed in a patient with CLL who had started allopurinol for a rising leukocytosis.Citation12 She was initially treated with prednisone with improvement in her transaminases and bilirubin but had a recurrence of transaminitis several months later during prednisone taper. Repeat biopsy demonstrated GCH and CLL. Her prednisone was increased, but she ultimately required therapy with rituximab due to persistent transaminitis. Several important points are demonstrated by each of the above patients: the prompt recognition of this rare entity in patients with CLL is important, and the clinical impact is varied from spontaneous resolution to death due to multisystem organ failure. Early recognition and treatment appears to be necessary to prevent liver-related complications including cirrhosis.

In our case series, all patients received treatment for GCH with steroids and a steroid-sparing agent, as well as CLL-directed treatment with anti-CD20 antibody, chemotherapy and/or ibrutinib. In Case 1, immunosuppression alone did not control the patient’s transaminitis. She ultimately required a combination of immunosuppression with cyclophosphamide/rituximab with ibrutinib for CLL-directed therapy. In Case 2, CLL-directed therapy with bendamustine-rituximab was not sufficient and he ultimately required long-term immunosuppression with azathioprine. In Case 3, the patient was treated with immunosuppression upfront with rituximab/prednisone but his transaminases did not normalize until the addition of the BTK inhibitor ibrutinib. Additionally, when his prednisone was tapered, his GCH flared and only improved with the addition of azathioprine for long-term immunosuppression. From our experience with GCH in CLL patients, we suggest that combinations of both immunosuppression (prednisone, anti-CD20 antibodies, and/or azathioprine) and CLL-directed therapy may be required to adequately control GCH and CLL as a potential stimulus for giant cell formation. GCH is not limited to advanced, heavily pretreated patients with CLL. Two patients in our series were diagnosed with GCH under active observation for CLL and untreated.

There is no consensus on the management of GCH in patients without CLL. Immunosuppression with corticosteroids and intravenous immunoglobulin has been utilized as first-line therapy.Citation15 The use of other modalities of immunosuppression including azathioprine has previously been reported in patients who are considered steroid-refractory. Rituximab has also been used in pediatric GCH with concomitant autoimmune hemolytic anemia (GCA-AHA), but to our knowledge has not been reported for use in adults.Citation16 In our series, corticosteroids were utilized upfront, and all three patients received anti-CD-20 antibodies as either monotherapy or in combination with other therapies, including cytotoxic therapies or ibrutinib. All patients also required azathioprine for long-term immunosuppression. Treatment with azathioprine has been described in pediatric cases as well as a case report of GCH in an elderly man.Citation17

In our cases, all patients received treatment with prednisone and an anti-CD20 antibody, though responses were varied. Ultimately, all patients received treatment with a CLL-directed agent as well as azathioprine for long-term immunosuppression. This combination was successful in all patients in this small case series, and importantly, no patients have evidence of long-term liver sequelae several years after treatment. As GCH has been associated with multiple etiologies, it may be present concomitantly with another cause of liver injury and should remain a concern in the setting of persistently elevated transaminases despite appropriate treatment of other causes (infection, cessation of offending medications, autoimmune hepatitis). Liver biopsy is required to distinguish GCH from other causes of transaminitis, including infectious, medication induced or related to CLL infiltration.

Hypogammaglobulinemia was present in two of our three cases, and these patients ultimately received IVIG replacement therapy. As IVIG has previously been used to treat autoimmune hepatitis, and it is unknown what role this may have played in their treatment. In our series, treatment of both CLL and GCH were required to improve liver dysfunction and inflammation. Unlike other published reports of CLL and GCH, all three patients (with a median follow up of 23 to 44 months) have not suffered long-term liver sequelae from GCH demonstrating that prompt recognition and early management of both CLL and GCH can prevent permanent liver dysfunction and death.

In conclusion, GCH is a rare clinical entity with variable presentations and responses to treatment. While rare, the diagnosis should be considered in patients with CLL with transaminitis without another attributable cause. Diagnosis requires liver biopsy and prompt intervention with a combination of immunosuppression (corticosteroids and consideration of steroid-sparing agents) and CLL directed therapy. In addition, these cases are an important reminder that the differential for liver dysfunction in CLL is broad and that liver biopsy should be considered in all unexplained cases, rather than assuming direct leukemic liver infiltration.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- Protzer U, Dienes HP, Bianchi L, Lohse AW, Helmreich-Becker I, Gerken G, Büschenfelde KHM. Post-infantile giant cell hepatitis in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis and autoimmune hepatitis. Liver. 1996;16(4):274–282. Epub 1996/08/01.PubMed PMID: 8878001. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0676.1996.tb00743.x.

- Torbenson M, Hart J, Westerhoff M, Azzam RK, Elgendi A, Mziray-Andrew HC, Kim GE, Scheimann A. Neonatal giant cell hepatitis: histological and etiological findings. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34(10):1498–1503. Epub 2010/ 09/28. PubMed PMID: 20871223. doi:10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181f069ab.

- Fang JW, Gonzalez-Peralta RP, Chong SK, Lau GM, Lau GM, Lau JY. Hepatic expression of cell proliferation markers and growth factors in giant cell hepatitis: implications for the pathogenetic mechanisms involved. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;52(1):65–72. Epub 2010/ 12/02. PubMed PMID: 21119537. doi:10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181f85a87.

- Phillips MJ, Blendis LM, Poucell S, Offterson J, Petric M, Roberts E, Levy GA, Superina RA, Greig PD, Cameron R. Syncytial giant-cell hepatitis. Sporadic hepatitis with distinctive pathological features, a severe clinical course, and paramyxoviral features. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(7):455–460. Epub 1991/02/14. PubMed PMID: 1988831. doi:10.1056/NEJM199102143240705.

- Tordjmann T, Grimbert S, Genestie C, Freymuth F, Guettier C, Callard P, Trinchet JC, Beaugrand M. [Adult multi-nuclear cell hepatitis. A study in 17 patients]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1998;22(3):305–310. Epub 1998/10/08.PubMed PMID: 9762216.

- Ben-Ari Z, Broida E, Monselise Y, Kazatsker A, Baruch J, Pappo O, Skappa E, Tur-Kaspa R. Syncytial giant-cell hepatitis due to autoimmune hepatitis type II (LKM1+) presenting as subfulminant hepatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(3):799–801. Epub 2000/03/10. PubMed PMID: 10710079. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01863.x.

- Micchelli ST, Thomas D, Boitnott JK, Torbenson M. Hepatic giant cells in hepatitis C virus (HCV) mono-infection and HCV/HIV co-infection. J Clin Pathol. 2008;61(9):1058–1061. Epub 2008/ 08/07. PubMed PMID: 18682418. doi:10.1136/jcp.2008.058560.

- Potenza L, Luppi M, Barozzi P, Rossi G, Cocchi S, Codeluppi M, Pecorari M, Masetti M, Di Benedetto F, Gennari W, et al. HHV-6A in syncytial giant-cell hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(6):593–602. Epub 2008/08/09. PubMed PMID: 18687640. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa074479.

- Fimmel CJ, Guo L, Compans RW, Brunt EM, Hickman S, Perrillo RR, Mason AL. A case of syncytial giant cell hepatitis with features of a paramyxoviral infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93(10):1931–1937. Epub 1998/10/15. PubMed PMID: 9772058. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00548.x.

- Alexopoulou A, Deutsch M, Ageletopoulou J, Delladetsima JK, Marinos E, Kapranos N, Dourakis SP. A fatal case of postinfantile giant cell hepatitis in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15(5):551–555. Epub 2003/04/19. PubMed PMID: 12702915. doi:10.1097/01.meg.0000050026.34359.7c.

- Gupta E, Yacoub M, Higgins M, Al-Katib AM. Syncytial giant cell hepatitis associated with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a case report. BMC Blood Disord. 2012;12:8. Epub 2012/07/21. PubMed PMID: 22812631; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3502519. doi:10.1186/1471-2326-12-8.

- Gupta N, Njei B. Syncytial giant cell hepatitis in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Dig Dis. 2015;16(11):683–688. Epub 2015/07/07. PubMed PMID: 26147671; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4824312. doi:10.1111/1751-2980.12273.

- van Oers MH, Kuliczkowski K, Smolej L, Petrini M, Offner F, Grosicki S, Levin M-D, Gupta I, Phillips J, Williams V, et al. Ofatumumab maintenance versus observation in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (PROLONG): an open-label, multicentre, randomised phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(13):1370–1379. Epub 2015/ 09/18. PubMed PMID: 26377300. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00143-6.

- Hartl J, Buettner R, Rockmann F, Farkas S, Holstege A, Vogel C, Schnitzbauer A, Schlitt HJ, Schoelmerich J, Kirchner G. Giant cell hepatitis: an unusual cause of fulminant liver failure. Z Gastroenterol. 2010;48(11):1293–1296. Epub 2010/ 11/03. PubMed PMID: 21043007. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1245476.

- Zachou K, Arvaniti P, Azariadis K, Lygoura V, Gatselis NK, Lyberopoulou A, Koukoulis GK, Dalekos GN. Prompt initiation of high-dose intravenous corticosteroids seems to prevent progression to liver failure in patients with original acute severe autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatol Res. 2018. Epub 2018/ 09/25. PubMed PMID: 30248210. doi:10.1111/hepr.13252.

- Paganelli M, Patey N, Bass LM, Alvarez F. Anti-CD20 treatment of giant cell hepatitis with autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Pediatrics. 2014;134(4):e1206–10. Epub 2014/09/10. PubMed PMID: 25201797. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-0032.

- Tajiri K, Shimizu Y, Tokimitsu Y, Tsuneyama K, Sugiyama T. An elderly man with syncytial giant cell hepatitis successfully treated by immunosuppressants. Internal Medicine. 2012;51(16):2141–2144. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.51.7870.