?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Follicular lymphoma (FL) accounts for approximately 35% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas and can progress to diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) at a rate of 2% per year. Here, we present a 56-year-old female patient who was diagnosed with grade 3a FL. Further pathological investigation revealed that the lymphoma had transformed into DLBCL following six courses of R-CHOP regimen, and further disease progression was observed after two courses of R2-GemOx. We ultimately failed to collect hematopoietic stem cells after two courses of R2-ICE. CD-22 CAR-T cell therapy salvaged the patient; however, a new soft tissue mass of 4.8 × 4.1 cm rapidly emerged in the patient’s right lung. Following the observation of strong tissue staining of PD-L1 (90%), the patient was administered PD-1 inhibitor and 26 Gy of radiotherapy and has maintained progression-free survival at more than 15 months of follow-up. Transformed FL with strong PD-L1 expression showed a poor response to standard immunochemotherapy. Our findings support the potential benefit of PD-1 inhibitor and combination therapies in this type of transformed FL.

Introduction

Follicular lymphoma (FL) accounts for ~20-25% of all new non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) diagnoses in western countriesCitation1 and is characterized by the occurrence of t(14;18) translocation, resulting in the over-expression of anti-apoptotic BCL2 protein.Citation2 Early recurrence after first-line chemotherapy occurs in about 20% of FL patients.Citation3 FLs in general do not express PD-L1, which may explain the poor efficacy of PD-1 inhibitors observed in this patient population. In a phase 2 study of nivolumab for relapsed/refractory FL followed up for 12 months, an overall response rate (ORR) of 4% (4/92) and median progression-free survival (PFS) of 2.2 months was reported.Citation4 Anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody therapy may therefore be associated with very limited activity in patients with relapsed or refractory (R/R) FL. Furthermore, approximately 28% of FL will transform into diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) within 10 years,Citation5 with a risk of 2% per year.Citation2 The curative effect of advanced-stage follicular lymphoma undergoing histologic transformation is not satisfactory. The present case report describes a meaningful alternative treatment strategy for patients with refractory tFL treated with an anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody and combination therapies.

Case presentation

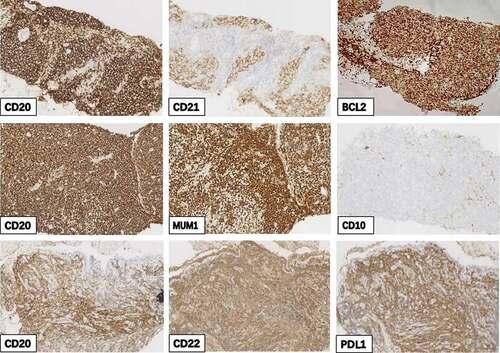

A 56-year-old woman presented with aggravated abdominal pain and night sweats with a duration of 3 days in September 2018. Laboratory test results revealed elevated 2-MG of 4

g/mL and extremely elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase at a level of 684 U/L. Epstein Barr virus (EBV)-DNA in whole blood was 8371 copies/mL and lymphocyte subsets showed that B-cell counts were extremely low at 5/μL. Computed tomography (CT) scanning of the abdomen revealed multiple enlarged lymph nodes. Subsequent positron emission tomography (PET)/CT scanning revealed the presence of multiple enlarged abdominopelvic cavities and retroperitoneal lymph nodes, the largest of which was 40 × 57 mm in the peripancreatic region with a high standardized uptake value of 41.9 (). PET/CT scanning has also indicated hepatosplenomegaly, with fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake significantly increased in multiple bone lesions. Histologic analysis of a core needle aspiration biopsy of the lymph node with the highest FDG uptake resulted in the following: CD20+ (), CD10-, BCL6+, Ki67 (70%+), C-MYC (40%+), MUM1+, CD21+ (), BCL2+ (), CD38-, CD5-, CD3-, EBER-, and CKpan-. Fluorescence in situ hybridization indicated a negative rearrangement of BCL2 and MYC. Bone marrow smear was normal. In consideration of the patient’s symptoms and immunohistochemistry findings, a diagnosis of FL grade 3a (stage IV, group B) with a high risk of FLIPI 3 points was made.

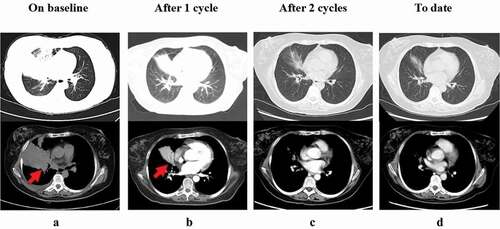

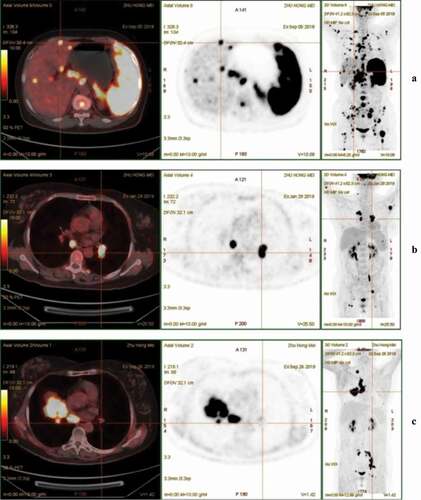

Figure 1. Whole-body PET/CT scan prior to treatment initiation (a). PET/CT imaging showed several enlarged or new lesions after six cycles of R-CHOP (b) and following CAR-T cell therapy (c)

Figure 2. Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining of three tissue biopsy samples. IHC staining of CD20 (a), CD21 (b), and BCL2 (c) in the first tissue biopsy samples. Positive IHC staining of CD20 (d) and MUM-1 (e) and negative staining of CD10 (f) in the second tissue biopsy samples. Positive staining of CD20 (g), CD22 (h), and PD-L1 (i) in the third tissue biopsy samples. (original magnification, 200×)

PET/CT after six courses of R-CHOP showed a clear response with metabolic normalization of multiple bone lesions; however, several new lesions appeared. A new left axillary lymph node was 14 × 15 mm with a high FDG uptake value of 37.8 (). Immunohistochemistry of the second pathological tissue in the left axillary lymph node revealed that FL had transformed into DLBCL (). Fluorescence in situ hybridization indicated a negative rearrangement of BCL2 and MYC and a positive rearrangement of BCL6. The patient was subsequently diagnosed with DLBCL of non-germinal center B-cell type (stage III, group B), age-adjusted IPI score 2, high-intermediate risk. Disease progression was observed after two courses of R2-GemOx. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) was considered as the patient had achieved partial remission (PR) after two courses of R2-ICE; however, this treatment strategy was not pursued due to failure of hematopoietic stem cell mobilization. After fludarabine and cyclophosphamide as lymphodepleting chemotherapy, the patient received approximately 5 × 106/kg of anti-CD22–4-1BB–CD3ζ chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR-T) cells. We used flow cytometry to detect the CD22-CAR. CAR-T cells expression in peripheral blood CD3+ cells increased to 30% in the first 10 days after infusion, then decreased gradually. On day 30 after CAR-T cell infusion, whole-abdomen enhanced CT scanning showed the patient developed progressive disease (PD) according to the Lugano classification. PET/CT evaluation on day 43 after CAR-T cell infusion discovered a significant increase in the emerging lesions, especially the right pulmonary hilum lymph node where a lesion of 4.8 × 4.1 cm in size with maximum standard unit value (SUVmax) of 32.4 was observed (). And at this time, we measured that the expression of CAR-T cells was decreased significantly. Given the expression of BCL2, the patient was administered venetoclax, but no response was observed. Core needle lung puncture on day 55 after CAR-T cell infusion revealed that the expression of PD-L1 was extremely high (90%) (). No significant mutations were discovered in second-generation sequencing. Considering the PD-L1 expression level, the PD-1 inhibitor sintilimab (200 mg) was administered on day 76 after the infusion and CAR-T cells were almost undetected at that time. Fortunately, the patient achieved partial remission (PR) after the first cycle of PD-1 inhibitor. Ten days later, 27 times radiotherapy (2 Gy each time) was carried out but was subsequently stopped because of grade 4 hematologic toxicity when the patient completed 26 Gy. Encouragingly, the patient has achieved sustained complete response (CR) with only PD-1 inhibitor treatment with about 15 months after cessation of radiotherapy (). PD-1 inhibitor and concurrent radiotherapy may mutually promote the efficacy in the treatment of this case, and the complete response might be considered as a result of combination therapies.

Discussion

FL can progress to aggressive lymphoma at an estimated rate of 2% per year, with the most common type of transformed lymphoma is DLBCL.Citation6 The majority of tFL cases (80%) have been shown to derive from the germinal-center B-cell–like subtype, while a considerable proportion (approximately 16%) derive from the activated B-cell–like (ABC) subtype. Of note, ABC subtype cases typically originate from FLs without BCL2 translocation,Citation7 which may in part contribute to the over-expression of ABC-like and late GCB cell phenotype signatures in t(14;18)-negative FL.Citation8 Previous studies have demonstrated that a key difference between patients with and without BCL2 rearrangement is that in t(14;18)-negative FL, new immunoglobulin N-glycosylation sites within the variable region of surface immunoglobulin (sIg) are rarely acquired during the somatic mutation of FL, which plays an important role in activating B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling bypass antigen presentation but interact with mannose-binding lectins expressed by macrophages and dendritic cells.Citation9,Citation10 Such a mechanism may result in activating BCR signaling by classical antigen presentation in t(14;18)-negative FL. Furthermore, anomalous signaling originating from tumor microenvironment or NFkB-associated genes, leading to the significant augmentation of gene mutations associated with immune response (IR) /inflammation or NFkB-signaling may also be an important mechanism driving pathogenesis of t(14;18)-negative FL.Citation10 Moreover, FL without BCL2 rearrangement is characterized by high expression of Ki67 and MUM1 and significant downregulation of CD10, with the latter event known to be associated with the absence of BCL2 expression in advanced-stage FL (p = .016).Citation11 These subtle but significant differences, including significant reduction in CD10 expression, enrichment of NF-kB signaling, and down-regulation of distinct microRNA profiles (e.g. miR-16, miR-26a, miR-101, miR-29 c and miR138), have been reported in t(14;18)-negative FL and are indicative of a “late” germinal center B-cell molecular phenotype in t(14;18)-negative FL.Citation10–12 This finding is consistent with the observation that t(14;18)-negative FL typically transforms into ABC-DLBCL.Citation7 Although t(14; 18)-negative FL has some specific molecular characteristics, in terms of initial therapeutic efficacy, no difference has been observed in survival duration or overall survival between FL patients with and without BCL2-break/t(14;18).Citation11 However, another study considered CD10-MUM1+ FL to be different from typical FL in molecular features and prognosis. CD10-MUM1+ FL were almost negative for BCL2 rearrangement, showed poor prognosis compared with CD10+ MUM1- FL, and 88% were accompanied by translocation or amplification of BCL6 gene.Citation13

FL patients with histological transformation (HT) have poor prognosis and short survival.Citation14 In the present case report, the patient with transformed DLBCL demonstrated an unsatisfactory response to various chemotherapy regimens. A previous study has reported that the CR rate of tFL patients after salvage chemotherapy was lower (50.3% vs 67.4%) and the disease progression rate was higher (28.2% vs 9.6%) compared with patients without transformation, and the median overall survival was 3.8 years.Citation15 Other studies have reported a 3-year overall survival (OS) rate of 44% among patients with early-stage FL undergoing HT, while those treated with R-CHOP at transformation had a 5-year OS rate of 66%.Citation6,Citation16 A poor curative effect was observed in our patient following multiple immunochemotherapy, and PD-1 inhibitor was subsequently initiated on the basis of high PD-L1 expression in the patient’s first tumor tissue biopsy.

Several studies have shown that PD-L1 is rarely expressed in FL tumor cells.Citation17,Citation18 In terms of therapeutic effect, in a phase 1 study of 10 R/R FL patients who were treated with nivolumab and had different levels of PD-L1 expression in nonmalignant immune cells within the tumor microenvironment, 1 CR (10%) and 3 partial responses (30%) were observed.Citation19 In a phase 2 trial of 29 relapsed FL patients, 19 (66%) obtained an objective response with a CR in 15/29 (52%) patients and a PR in 4/29 (14%) patients following treatment with pidilizumab combined with rituximab.Citation20 The efficacy of PD-1 inhibitor treatment in DLBCL remains unsatisfactory. In a phase 2 study, 121 R/R DLBCL patients who were unsuitable for or had failed with autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (auto-HCT) received nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks. ORR was 10% in the auto-HCT-failed cohort and 3% in the auto-HCT-ineligible cohort, while median PFS was 1.9 and 1.4 months and OS was 12.2 and 5.8 months, respectively.Citation21 A few clinical trials of PD-1/PD-L1 blockade as monotherapy or combination therapy in FL, tFL, or DLBCL patients are currently underway (). We observed strong expression of PD-L1 in the patient’s first tumor tissue, and inferred from this finding that immune evasion might play a decisive role in tFL disease progression. We propose several factors which may have contributed to the high expression of PD-L1 in this case. First, tumor cells, antigen-presenting cells (APC), and myeloid suppressor cells (MDSC) in the tumor microenvironment can upregulate PD-L1 expression when stimulated by inflammatory cytokines during antitumor immune responses, leading to adaptive immune resistance.Citation22,Citation23 Furthermore, EBV-related FL has a higher rate of transformation to DLBCL; however, the relationship between EBV and FL remains poorly understood.Citation24 EBV infection may also play an important role in the development and/or progression of some FLs, and several studies have demonstrated elevated PD-L1 expression in EBV-infected lymphomas such as CHL and DLBCL.Citation25,Citation26 In this case, the EBV-DNA was significantly increased when the patient was diagnosed with follicular lymphoma for the first time. And at that time, lymphocyte subsets showed that B-cell counts were extremely low at 5/μL. Therefore, we doubted that EBV may have a disfunction effect on the immune system. However, the correlation between EBV and the type of lymphoma in this patient remains unclear.

Table 1. Ongoing clinical trials of PD-1/PD-L1 blockade as monotherapy or combination therapy in FL, tFL, or DLBCL

Immunosuppressive checkpoint inhibitors and CAR-T cell therapy are approved treatments for a variety of hematological malignancies. Several studies have reported the efficacy of CAR-T cell therapy in patients with FL and tFL. Among 14 patients with R/R FL and 14 with R/R DLBCL receiving anti-CD19 CAR-T cell therapy, CR occurred in 71% of patients in the FL cohort and in 43% in the DLBCL cohort. Moreover, 89% of responding FL patients and 86% of responding DLBCL patients had sustained remission at a median follow-up of 28.6 months.Citation27 A phase 1/2 clinical trial in 8 R/R FL and 13 tFL patients demonstrated CR of 88% with FL and 46% with tFL following the infusion of 2 × 106 CD19-CAR-T cells/kg.Citation28 However, few reports to date have evaluated the clinical outcome of CAR-T cell therapy combined with anti-PD-1 antibody therapy in B-NHL. In a single-center study among 11 R/R B-NHL patients who received a single dose of 3 mg/kg nivolumab on the third day after receiving a median of 8 × 106/kg CD19 CAR-T cells infusion, ORR of 81.8% was observed, with CR and PR of 45.5% and 36.3%, respectively.Citation29 More importantly, all reported toxicities were evaluated as manageable and temporary. In another case of refractory FL treated by CD19 CAR-T cell infusion combined with a reduced dose of nivolumab (1.5 mg/kg), complete remission for 16 months was reported at the time of publication.Citation30 After CAR-T cell therapy failure, we determined that CD22 expression remained positive, ruling out antigen loss as a contributing factor. Given the strong expression of PD-L1 in this unique tFL patient, we speculate that PD-L1 over-expression may lead to T cell dysfunction, in line with findings from a previous study.Citation31 Furthermore, CAR-T cells may produce pro-inflammatory cytokines which can contribute to increased expression of PD-L1.Citation32 Taken together with the observations from our present case study, these earlier findings support the efficacy of therapeutic strategies which block the inhibitory interaction of PD-1/PD-L1 to enhance anti-tumor CAR-T cells efficacy in this patient population. A phase 1/2 study of pembrolizumab in patients who failed to respond to or relapsed after anti-CD19 CAR-T cell therapy for R/R CD19+ lymphomas including FL is in progress (NCT02650999). Recently, modified CAR-T cells which secrete PD-1-blocking single-chain variable fragments (scFv) have been shown to improve the anti-tumor activity of CAR-T cells and bystander tumor-specific T cells with low toxicity, as secreted scFvs remained localized to the tumor.Citation33 This CAR-T modification appears to be more effective than combination therapy. However, further clinical studies are needed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of combination therapy or ‘armored’ CAR-T cell therapy in transformed FL.

In conclusion, we report successful PD-1 inhibitor treatment in a patient with refractory tFL who failed to respond to CAR-T cell therapy. Standard tFL therapies are characterized by aggressive clinical courses and poor outcomes which may be attributable to immune evasion. The findings of the present case report indicate that clinical benefit in this type of FL may depend on the synergistic effect of PD-1 inhibitors and combination therapies instead of traditional multi-protocol chemotherapy, and highlight the potential activity of monotherapy PD-1 inhibitors in FL with high expression of PD-L1. However, further studies are required to confirm whether PD-1 inhibitors alone and in combination therapy are more effective for the treatment of FL compared with existing treatments, and whether the level of PD-L1 expression affects the treatment response and survival rate.

Informed consent statement

Informed written consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this report and any accompanying images.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (707 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website

Additional information

Funding

References

- Carbone A, Roulland S, Gloghini A, Younes A, von Keudell G, López-Guillermo A, Fitzgibbon J. 2019. Follicular lymphoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 5(1):83. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-019-0132-x.

- Freedman A, Jacobsen E. 2020. Follicular lymphoma: 2020 update on diagnosis and management. Am J Hematol. 95(3):316–327. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.25696.

- Casulo C, Byrtek M, Dawson KL, Zhou X, Farber CM, Flowers CR, Hainsworth JD, Maurer MJ, Cerhan JR, Link BK, et al. 2015. Early relapse of follicular lymphoma after rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone defines patients at high risk for death: an analysis from the national lymphocare study. J Clin Oncol. 33(23):2516–2522. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2014.59.7534.

- Armand P, Janssens A, Gritti G, Radford J, Timmerman J, Pinto A, Mercadal Vilchez S, Johnson P, Cunningham D, Leonard JP, et al. 2021. Efficacy and safety results from CheckMate 140, a phase 2 study of nivolumab for relapsed/refractory follicular lymphoma. Blood. 137(5):637–645. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2019004753.

- Montoto S, Davies AJ, Matthews J, Calaminici M, Norton AJ, Amess J, Vinnicombe S, Waters R, Rohatiner AZ, Lister TA. 2007. Risk and clinical implications of transformation of follicular lymphoma to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 25(17):2426–2433. doi:https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2006.09.3260.

- Link BK, Maurer MJ, Nowakowski GS, Ansell SM, Macon WR, Syrbu SI, Slager SL, Thompson CA, Inwards DJ, Johnston PB, et al. 2013. Rates and outcomes of follicular lymphoma transformation in the immunochemotherapy era: a report from the University of Iowa/MayoClinic specialized program of research excellence molecular epidemiology resource. J Clin Oncol. 31(26):3272–3278. doi:https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2012.48.3990.

- Kridel R, Mottok A, Farinha P, Ben-Neriah S, Ennishi D, Zheng Y, Chavez EA, Shulha HP, Tan K, Chan FC, et al. 2015. Cell of origin of transformed follicular lymphoma. Blood. 126(18):2118–2127. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2015-06-649905.

- Leich E, Salaverria I, Bea S, Zettl A, Wright G, Moreno V, Gascoyne RD, Chan WC, Braziel RM, Rimsza LM, et al. 2009. Follicular lymphomas with and without translocation t(14;18) differ in gene expression profiles and genetic alterations. Blood. 114(4):826–834. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2009-01-198580.

- Strout MP. 2015. Sugar-coated signaling in follicular lymphoma. Blood. 126(16):1871–1872. doi:https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2015-08-665141.

- Zamò A, Pischimarov J, Schlesner M, Rosenstiel P, Bomben R, Horn H, Grieb T, Nedeva T, López C, Haake A, et al. 2018. Differences between BCL2-break positive and negative follicular lymphoma unraveled by whole-exome sequencing. Leukemia. 32(3):685–693. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2017.270.

- Leich E, Hoster E, Wartenberg M, Unterhalt M, Siebert R, Koch K, Klapper W, Engelhard M, Puppe B, Horn H, et al. 2016. Similar clinical features in follicular lymphomas with and without breaks in the BCL2 locus. Leukemia. 30(4):854–860. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2015.330.

- Leich E, Zamo A, Horn H, Haralambieva E, Puppe B, Gascoyne RD, Chan WC, Braziel RM, Rimsza LM, Weisenburger DD, et al. 2011. MicroRNA profiles of t(14;18)-negative follicular lymphoma support a late germinal center B-cell phenotype. Blood. 118(20):5550–5558. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2011-06-361972.

- Karube K, Guo Y, Suzumiya J, Sugita Y, Nomura Y, Yamamoto K, Shimizu K, Yoshida S, Komatani H, Takeshita M, et al. 2007. CD10-MUM1+ follicular lymphoma lacks BCL2 gene translocation and shows characteristic biologic and clinical features. Blood. 109(7):3076–3079. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2006-09-045989.

- Sarkozy C, Maurer MJ, Link BK, Ghesquieres H, Nicolas E, Thompson CA, Traverse-Glehen A, Feldman AL, Allmer C, Slager SL, et al. 2019. Cause of death in follicular lymphoma in the first decade of the rituximab era: a pooled analysis of French and US cohorts. J Clin Oncol. 37(2):144–152. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.18.00400.

- Sarkozy C, Trneny M, Xerri L, Wickham N, Feugier P, Leppa S, Brice P, Soubeyran P, Gomes Da Silva M, Mounier C, et al. 2016. Risk factors and outcomes for patients with follicular lymphoma who had histologic transformation after response to first-line immunochemotherapy in the PRIMA trial. J Clin Oncol. 34(22):2575–2582. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2015.65.7163.

- Bains P, Al Tourah A, Campbell BA, Pickles T, Gascoyne RD, Connors JM, Savage KJ. 2013. Incidence of transformation to aggressive lymphoma in limited-stage follicular lymphoma treated with radiotherapy. Ann Oncol. 24(2):428–432. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mds433.

- Dorfman DM, Brown JA, Shahsafaei A, Freeman GJ. 2006. Programmed death-1 (PD-1) is a marker of germinal center-associated T cells and angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 30(7):802–810. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/01.pas.0000209855.28282.ce.

- Andorsky DJ, Yamada RE, Said J, Pinkus GS, Betting DJ, Timmerman JM. 2011. Programmed death ligand 1 is expressed by non-hodgkin lymphomas and inhibits the activity of tumor-associated T cells. Clin Cancer Res. 17(13):4232–4244. doi:https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-10-2660.

- Lesokhin AM, Ansell SM, Armand P, Scott EC, Halwani A, Gutierrez M, Millenson MM, Cohen AD, Schuster SJ, Lebovic D, et al. 2016. Nivolumab in patients with relapsed or refractory hematologic malignancy: preliminary results of a phase Ib study. J Clin Oncol. 34(23):2698–2704. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2015.65.9789.

- Westin JR, Chu F, Zhang M, Fayad LE, Kwak LW, Fowler N, Romaguera J, Hagemeister F, Fanale M, Samaniego F, et al. 2014. Safety and activity of PD1 blockade by pidilizumab in combination with rituximab in patients with relapsed follicular lymphoma: a single group, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 15(1):69–77. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(13)70551-5.

- Ansell SM, Minnema MC, Johnson P, Timmerman JM, Armand P, Shipp MA, Rodig SJ, Ligon AH, Roemer MGM, Reddy N, et al. 2019. Nivolumab for relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in patients ineligible for or having failed autologous transplantation: a single-arm, phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 37(6):481–489. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.18.00766.

- Zolov SN, Rietberg SP, Bonifant CL. 2018. Programmed cell death protein 1 activation preferentially inhibits CD28.CAR-T cells. Cytotherapy. 20(10):1259–1266. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcyt.2018.07.005.

- Chen S, Crabill GA, Pritchard TS, McMiller TL, Wei P, Pardoll DM, Pan F, Topalian SL. 2019. Mechanisms regulating PD-L1 expression on tumor and immune cells. J Immunother Cancer. 7(1):305. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s40425-019-0770-2.

- Mackrides N, Campuzano-Zuluaga G, Maque-Acosta Y, Moul A, Hijazi N, Ikpatt FO, Levy R, Verdun RE, Kunkalla K, Natkunam Y, et al. 2017. Epstein-Barr virus-positive follicular lymphoma. Mod Pathol. 30(4):519–529. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2016.214.

- Green MR, Rodig S, Juszczynski P, Ouyang J, Sinha P, O’Donnell E, Neuberg D, Shipp MA, Constitutive AP-1. 2012. activity and EBV infection induce PD-L1 in Hodgkin lymphomas and posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders: implications for targeted therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 18(6):1611–1618. doi:https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-11-1942.

- Chen BJ, Chapuy B, Ouyang J, Sun HH, Roemer MG, Xu ML, Yu H, Fletcher CD, Freeman GJ, Shipp MA, et al. 2013. PD-L1 expression is characteristic of a subset of aggressive B-cell lymphomas and virus-associated malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 19(13):3462–3473. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-13-0855.

- Schuster SJ, Svoboda J, Chong EA, Nasta SD, Mato AR, Anak Ö, Brogdon JL, Pruteanu-Malinici I, Bhoj V, Landsburg D, et al. 2017. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells in refractory B-cell lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 377(26):2545–2554. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1708566.

- Hirayama AV, Gauthier J, Hay KA, Voutsinas JM, Wu Q, Pender BS, Hawkins RM, Vakil A, Steinmetz RN, Riddell SR, et al. 2019. High rate of durable complete remission in follicular lymphoma after CD19 CAR-T cell immunotherapy. Blood. 134(7):636–640. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2019000905.

- Cao Y, Lu W, Sun R, Jin X, Cheng L, He X, Wang L, Yuan T, Lyu C, Zhao M. 2019. Anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T cells in combination with nivolumab are safe and effective against relapsed/refractory B-cell non-hodgkin lymphoma. Front Oncol. 9:767. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2019.00767.

- Wang J, Deng Q, Jiang YY, Zhang R, Zhu HB, Meng JX, Li YM. 2019. CAR-T 19 combined with reduced-dose PD-1 blockade therapy for treatment of refractory follicular lymphoma: a case report. Oncol Lett. 18(5):4415–4420. doi:https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2019.10783.

- Fry TJ, Shah NN, Orentas RJ, Stetler-Stevenson M, Yuan CM, Ramakrishna S, Wolters P, Martin S, Delbrook C, Yates B, et al. 2018. CD22-targeted CAR T cells induce remission in B-ALL that is naive or resistant to CD19-targeted CAR immunotherapy. Nat Med. 24(1):20–28. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.4441.

- Tanoue K, Rosewell Shaw A, Watanabe N, Porter C, Rana B, Gottschalk S, Brenner M, Suzuki M. 2017. Armed oncolytic adenovirus-expressing PD-L1 mini-body enhances antitumor effects of chimeric antigen receptor T cells in solid tumors. Cancer Res. 77(8):2040–2051. doi:https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.Can-16-1577.

- Rafiq S, Yeku OO, Jackson HJ, Purdon TJ, van Leeuwen DG, Drakes DJ, Song M, Miele MM, Li Z, Wang P, et al. 2018. Targeted delivery of a PD-1-blocking scFv by CAR-T cells enhances anti-tumor efficacy in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 36(9):847–856. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.4195.