ABSTRACT

What opportunities and trade-offs do de facto states encounter in developing economic ties with the outside world? This article explores the complex relationship between trade and trust in the context of contested statehood. Most de facto states are heavily dependent on an external patron for economic aid and investment. However, we challenge the widespread assumption that de facto states are merely hapless pawns in the power-play of their patrons. Such an approach fails to capture the conflict dynamics involved. Drawing on a case study of Abkhazia, we explore how this de facto state navigates between its “patron”Russia, its “parent state”Georgia, and the EU. The conflict transformation literature has highlighted the interrelationship between trust and trade – but how does this unfold in the context of continued nonrecognition and contested statehood? Does trade serve to facilitate trust and hence prospects for conflict transformation? With Abkhazia, we find scant correlation between trust and trade: in the absence of formal recognition, trade does not necessarily facilitate trust. However, the interrelationship between trade, trust, and recognition proves more complex than expected: we find less trust in the patron and more trade with the parent than might have been anticipated.

The past decade has seen a surge in scholarship on the “contested neighborhood” between Russia and the EU, in particular regarding Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia (see, e.g., Averre Citation2009; Ademmer, Delcour, and Wolczuk Citation2016; Delcour Citation2017). However, there has been less systematic research on how the neighborhood’s de facto statesFootnote1 – the unrecognized secessionist entities existing on the territories of these three states – navigate between Russia, the EU, and the states they seek to break away from (for notable exceptions, see Cooley and Mitchell Citation2010; Frear Citation2014; Comai Citation2018; Jaksa Citation2019).

In most cases, a de facto state will be heavily dependent on an external patron for economic aid and investment (Blakkisrud and Kolstø Citation2012; Kolstø Citation2020). This dependency is usually exacerbated by the actions of the parent state – the state from which the de facto state seeks to break away – which often responds to the secessionist bid by imposing sanctions or economic blockades (Ker-Lindsay Citation2012). In light of continued nonrecognition, economic interaction with the world beyond patron and parent remains severely restricted, with the de facto states barred from joining international trade regimes or engaging in formalized trade (Kemoklidze and Wolff Citation2020). However, we argue, treating de facto states as hapless pawns in the patron’s power-play detracts from our understanding of conflict dynamics: de facto states do enjoy (bounded) agency.

Here we examine how Abkhazia, one of the de facto states of this “contested neighborhood”, navigates between Russia as “patron,” the Georgian “parent state,” and the EU in the sphere of trade and economic interaction. As such processes are complex, multi-faceted, and interdependent, we adopt both an inside–out perspective (from the viewpoint of the de facto state) and an outside–in one (presenting the approaches of Brussels, Moscow, and Tbilisi).Footnote2 What opportunities and trade-offs do the de facto state authorities encounter in developing economic ties with the patron, parent, and other external actors (here: the EU)? Can trade under conditions of continued nonrecognition facilitate trust, and hence prospects for conflict transformation? And can the de facto state change policy along one vector, without this negatively affecting the other two? In short, what room for independent economic agency does Abkhazia have within the triangular relationship involving Russia, Georgia proper, and the EU?

We start by examining the role played by trust (and distrust) in fostering economic relations in a postwar context. Then we briefly outline Abkhazia’s postwar quest for consolidating de facto statehood and developing ties with the outside world, before exploring the development of economic interaction with Russia, Georgia proper, and the EU. In conclusion, we argue that the Abkhaz case demonstrates that, in the absence of formal recognition, trade does not necessarily facilitate trust. However, the interrelations between trade, trust, and recognition prove more complex than one might have expected.

Trust and economic relations across borders

All de facto states that survive for some time must engage in trade with the outside world. Their economies are normally small, and autarchy is not an option – de facto states simply cannot produce the necessary range of goods themselves. However, lack of international recognition prevents them from joining international trade regimes, pushing their economic interactions with the outside world into the “gray zones” of semi-legal international trade. In the absence of formal regulatory frameworks, trust becomes an important factor (see Nordstrom Citation2000).

Scholars generally agree that “trust refers to an attitude involving a willingness to place the fate of one’s interests under the control of others” (Hoffman Citation2002, 377; see also Kydd Citation2005; Hoffman Citation2006; Wheeler Citation2018). In “communal relationships” (like marriage or friendship), trust may be taken for granted. In “exchange relationships,” however, trust “must be built and tested over time” (Kelman Citation2005, 640; see also Evensky Citation2011; Anomaly Citation2017). Here each party is seen as primarily acting out of self-interest, but it is also assumed that other parties are interested in making the relationship work and will therefore “act in a trustworthy fashion” (Kelman Citation2005, 646).

In a post-secession context, as with de facto states, mutual trust is at low ebb. The “exchange relationship” is characterized by mutual distrust: “Both parties believe – usually with a long history of supporting evidence – that the other is bent on frustrating their needs, on undermining their welfare, and on causing them harm” (Kelman Citation2005, 640; see also Hoffman Citation2006, 8).

How to re-build trust where there is little or none? The conflict transformation literature has highlighted the role of trade in fostering trust/confidence-building (see Kelman Citation2005; Hegre, Oneal, and Russett Citation2010; Rohner, Thoenig, and Zilibotti Citation2013; Kemoklidze and Wolff Citation2020). Increased trust will in turn facilitate further trade by lowering the transaction costs.

When the actors are trustworthy, transaction costs shrink because they can be counted on to keep their commitments, even when both parties understand that there are opportunities to capture material rewards by violating them (Anomaly Citation2017, 99). Of course, trade can take place also without trust, but then usually on a smaller scale and less advantageous terms (Evensky Citation2011, 250–251), as extra transaction costs must be calculated into the price of the commodity/service. Less-trusted partners will have to sell their goods at a lower price and pay more for what they buy.

In the case of “regular” inter- or intrastate conflicts, domestic legislation or international legal frameworks can facilitate the process of re-building trust through trade: any defecting partner may be taken to court. Finding themselves outside the purview of the international court system and legal framework for transnational commerce, de facto states face a structural challenge: the lack of formal recognition creates a massive commitment problem in business transactions. In the absence of formal institutions and regimes regulating trade, trust becomes particularly important – but there is also a potential negative spiral involved: low levels of trust in a post-secessionist context may obstruct the further development of trade, and what limited trade there is fails to translate into increased trust.

Here we focus primarily on trust between state actors. Drawing on insights from the conflict transformation literature, however, we will in the case of the conflicting sides (Abkhazia and Georgia) also explore whether an increase in trade and trust among ordinary people contributes to an increase in trust on the state level. From Abkhazia’s recent history and contested formal status, we expect to find variations in trust and hence opportunities for trade along our three vectors:

Patron: Russia was the first country to officially recognize Abkhazia’s independence in 2008; since then, Russia has provided security guarantees and generous economic assistance. From this, we would expect high levels of trust and extensive trade and economic interaction with Russia.

Parent state (Georgia): Abkhazia fought a bitter war of secession 1992–1993. Distrust of Georgia based on war-time experiences has been exacerbated by the Georgian economic blockade and, since 2008, Georgian legislation defining all economic activity on Abkhaz territory – unless explicitly approved by Tbilisi – as illegal. We would therefore expect mutual trust to be very low, and economic interaction likewise limited.

The EU: On paper, trade and economic interaction with the EU seems attractive – a huge market and a potential for FDI without historical baggage in the form of repression and domination (unlike in Abkhazia’s relations with both parent and patron). However, given the EU’s political backing of Tbilisi and its policy of “engagement without recognition,” we nevertheless expect trade and trust to be low.

Overcoming postwar economic dislocation: Abkhazia’s relations with the outside world

In Soviet times, Abkhazia was seen as an affluent part of the USSR, a coveted tourist destination with a pleasant climate and well-developed infrastructure – but war-time destruction, isolation, and lack of international recognition took their toll on the economy. According to one estimate, the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the subsequent war of secession brought damages costing between 11 and 13 billion USD to the Abkhaz economy (Kolossov and O’Loughlin Citation2011, 637). In the immediate postwar years, the economy regressed to subsistence level, with the urban population dependent on supplies from relatives living in the countryside, and government officials being paid in loaves of bread (Kolstø and Blakkisrud Citation2008, 494).

Only very gradually was the massive economic dislocation overcome. With Abkhazia subjected to political and economic isolation, reconstruction was slow. The lack of international recognition meant that trade as well as foreign investment and loans were basically off the table. To survive, the Abkhaz had to resort to informal solutions and practices (Prelz Oltramonti Citation2017). SukhumiFootnote3 also tried to mobilize the sizable Abkhaz diaspora; in the 1990s, the ethnic Abkhaz in Turkey provided one of very few trade links with the outside world,Footnote4 as well as some limited investment in the economy (Punsmann Citation2009). Only after the turn of the millennium were the Abkhaz authorities able to make a dent in the blockade, with Moscow finally responding more favorably to Sukhumi’s overtures.

This gradual easing of the economic blockade on the northern border culminated in 2008 when, in the aftermath of the August Russo–Georgian War, Moscow became the first country to officially recognize Abkhazia’s independence, assuming full patronship over the de facto state. Since then, the Abkhaz economy has grown rapidly. According to Minister of Economy Adgur Ardzinba (2015–2020), Abkhazia’s GDP almost doubled between 2008 and 2018 (Sputnik Citation2018).Footnote5 But this has come at a price: strong unilateral, asymmetric dependence on the patron.

Whereas some Abkhaz do not object to their republic becoming an economic appendage of Russia as long as the patron continues to provide security and ensure Abkhazia’s material well-being, others see independence as a “historical responsibility” (Inal-Ipa and Shakryl Citation2011). The latter argue that the massive economic dependence on Russia detracts from the goal of realizing full-fledged sovereignty and thus threatens Abkhaz identity and sovereignty (Kolossov and O’Loughlin Citation2011, 640).Footnote6

To balance the dependence on the patron, Abkhaz politicians have long discussed how to develop mnogovektornost’ (multi-vectoralism): developing Abkhazia’s political and economic relations along other lines, not only toward the northern neighbor (see e.g. Regnum Citation2008; Shariya Citation2013). This means a delicate balancing act: while seeking to break the international isolation, the authorities must also assure their patron of Sukhumi’s continued loyalty. Already in December 2008, President Sergei Bagapsh (2005–2011) lamented that whenever he mentioned mnogovektornost’ in relation to Abkhazia’s foreign policy, opinions would appear in the Abkhaz press claiming that

“Bagapsh has turned his back on Russia and is turning toward the West.” But our policy ought to be mnogovektornyi (multi-vector). However, in politics there is also another concept, prioritetnost’ (prioritization). Our priority is first and foremost the Russian Federation. Russia has recognized us; it has assumed great responsibility. But I repeat–we are ready to talk with any state who wants to talk with us as an equal with an equal (Regnum Citation2008).

In the ensuing years, Abkhazia signed several bilateral agreements providing for closer political and economic integration with the Russian Federation (see below). However, developments after the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014 have re-activated the mnogovektornost’–prioritetnost’ question: In an increasingly polarized international context, what room does Abkhazia have for developing alternatives that can balance its economic dependency on the patron for trade and investment?

Trade and economic relations with the patron state

Today, when Russian patronhood is taken for granted, the complicated history of early postwar relations between Abkhazia and Russia is often forgotten. During the war of secession, locally stationed Russian troops helped turn the tide in favor of the Abkhaz. However, Moscow was not ready to back an Abkhaz bid for full independence. The involvement on the Abkhaz side of irregular fighters from the North Caucasus, as well as Russia’s own problems with the brewing secessionist conflict in Chechnya, meant that Moscow initially kept the de facto state authorities at arm’s length. Seen from Moscow, getting Georgia back into the fold was a bigger prize; when Tbilisi in December 1993 agreed to join the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), the Kremlin switched its priorities.

Already in September 1993, Russia had closed its border with the breakaway republic and cut off the supply of electricity and telecommunications (Akaba and Gitsba Citation2011, 8–9). In December 1994, from the onset of the war in Chechnya onwards, all males aged 16–60 were banned from crossing the border. In 1996, Russia joined a CIS blockade that virtually isolated Abkhazia from the outside world. Sukhumi did look to Moscow – and not least to the neighboring Russian regions – for support; but Moscow did not actively seek the role of a patron. Abkhazia was left to its own devices, cut off from its northern neighbor, with trade restricted to whatever goods women and children could carry across the border-point at Psou (Punsmann Citation2009).

From the turn of the millennium, however, Moscow gradually began to cooperate more closely with the de facto authorities in Sukhumi. The travel ban was lifted in September 1999, and, from 2000, the economic blockade was gradually eased. The major turnabout came with the 2008 war. Shortly prior to the armed conflict, Russia had abandoned the last remaining restrictions related to the 1996 CIS embargo. With the 2008 Russian recognition of Abkhazia as an independent state, economic cooperation shifted to a new level.

Recognition was followed by generous economic support, giving a much-needed impetus to the Abkhaz economy. Since 2008, Moscow has poured funding into Abkhazia, in the initial years covering up to 75% of the de facto state’s budget, gradually dropping to around 50% (RIA Novosti Citation2018). Russian financial assistance partly covers regular budget expenditures (including education, health, and police), and partly funds a bilateral investment program directed mainly toward infrastructure development (ICG Citation2018, 31–33; Gaprindashvili et al. Citation2019, 12). This program has been running in three-year cycles since 2013. Gradually, with some major infrastructure projects completed, focus has shifted to include the real economy (the flow of goods and services), introducing, among other things, a program for cheap loans to medium-sized (and in the Abkhaz context) large enterprises, to boost exports and tax revenues (RIA Novosti Citation2018).

The Abkhaz authorities have also concluded a range of bilateral agreements facilitating closer integration with Russia (Ambrosio and Lange Citation2016). Important milestones are the 2008 Agreement on Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance and the 2014 Agreement on Alliance and Strategic Partnership. According to the latter, “The main directions of the development of the alliance and strategic partnership are: (…) the formation of a common social and economic space” between Abkhazia and Russia (Dogovor Citation2014). Economic interaction with Russia is further regulated by additional treaties, including the 2009 Agreement on the Promotion and Reciprocal Protection of Investments and the 2012 Agreement on the Regime of Trade in Goods (Aleksandrov and Papaskiri Citation2017). These agreements foresee close integration of the two economies. For example, the preamble to the 2012 agreement states that the goal is to create “a single market of goods, services, capital, and labor” (Soglashenie Citation2012). Among specific steps for reaching this goal, it lists the elimination of customs duties on bilateral trade.

Unsurprisingly, Russia has become Abkhazia’s most important trading partner by far – it was already the principal partner prior to Russian recognition. Today it is for all practical purposes the only country with which Abkhazia can engage in legalized trade, as none of the few other states that have recognized Abkhazia are located nearby or are natural trading partners.Footnote7 As a result of the trade agreements and harmonization of rules and regulations, trade has soared. According to Abkhaz Minister of Economy Adgur Ardzinba, in the first ten years after recognition, Abkhazia’s foreign trade turnover tripled, with exports growing six-fold (Sputnik Citation2018). While the Russian economy has struggled to adapt to the sanctions and counter-sanctions imposed in 2014 in connection with the conflict in eastern Ukraine, the Abkhaz Ministry of Economy has seen these sanctions as a window of opportunity:

The current foreign economic situation (…) opens up good opportunities for promoting Abkhaz goods to the largest market in the region with the possibility of developing a significant share in sectors where Abkhazia has strong traditions (agriculture, including agricultural processing, production of food, alcoholic beverages, fish and seafood, etc.) (Ministerstvo ekonomiki Respubliki Abkhaziya Citation2017).

According to Abkhaz official statistics, in 2019 Russia stood for 70% of all Abkhaz trade (76% of Abkhaz exports, and 68% of Abkhazia’s imports) (Sputnik Citation2020).Footnote8 Trade turnover of the two countries amounted to 280.4 million USD (ibid.). However, trade is extremely lopsided, with the Abkhaz side running a huge deficit: in 2019, the value of Russian exports to Abkhazia was 210.9 million USD, while that of Abkhazia to Russia was only 69.5 million USD. Given the extensive trade and economic interaction between Abkhazia and its patron, mutual trust could be expected to be high. Closer examination of the Abkhaz tourism industry, a traditional economic mainstay, as well as Russian direct investments, reveals that this is not necessarily the case.

Before 1991, the number of tourists from Russia and other parts of the former USSR to the “Soviet Cote d’Azur” stood at around 2.5–3 million per year. The war and subsequent embargo brought this flourishing industry to a virtual standstill, but in recent years, the sector has seen a revitalization, with approx. 90% of all visitors arriving from Russia (Agumova Citation2018). For Russian tourists, the Abkhaz Black Sea Coast represents a popular low-cost alternative to Turkey or destinations in the Middle East, with the further advantages of being Russian-speaking and within the ruble zone.Footnote9

Abkhaz tourist industry has benefitted when the Russian authorities, for various reasons, have temporarily denied their nationals travel to, for example, Turkey or Egypt. However, Abkhazia’s reliance on a single market makes it vulnerable to the political whims of Moscow, and the industry has been hard hit by Russian campaigns promoting Crimea as a now-domestic alternative. Moreover, these campaigns have been accompanied by media reports of Abkhaz resorts offering poor service and, even worse, plagued with rampant crime (Chablin and Skakov Citation2019). The Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued a travel advice warning potential tourists:

the level of criminality in Abkhazia is extremely high. Most common are theft (mostly smaller belongings), robbery, hooliganism, and swindle. Theft of money (often also with documents) takes place on beaches, in private apartments, and from parked cars (Konsul’skiy informatsionnyy portal Citationn.d.).

The negative PR has had an impact: the tourist inflow peaked in 2015 with 1.5 million annual visitors; since, the figure has hovered around 1 million (Esiava Citation2019).Footnote10

As for FDI, although Abkhazia has officially given priority to Russian investment,Footnote11 Russian businesspeople often find Abkhazia a difficult place to work.Footnote12 Even a major Russian corporation like Rosneft, which enjoys full Kremlin backing, has struggled. In 2010, Rosneft established a joint company with the Abkhaz government, RN-Abkhaziya, to explore the Abkhaz shelf. In 2015, however, the parliamentary majority raised objections to the deal, citing ecological concerns (Stateynov Citation2019). This was widely perceived as an excuse aimed at favoring business interests with connections to the new power-holders in Sukhumi (Dzhopua Citation2015).Footnote13 Rosneft pointed out that the plans for exploration of the shelf had been agreed during Putin’s visit to Abkhazia in 2009 and hence enjoyed support at the highest political level in Russia (Stateynov Citation2019), but to no avail. The case dragged on for years: not until 2019 did the Abkhaz government finally reconfirm the validity of the license. Back in 2015, the opposition had duly noted, “such actions would negatively affect the repute of Abkhazia in the eyes of Russian business circles, as well as the investment attractiveness of the republic as a whole” (Dzhopua Citation2015). Despite the government’s belated volte face, the opposition was probably proven right: the handling of the Rosneft affair undoubtedly did considerable damage to Abkhazia’s reputation as a reliable business partner and to trust between Russian and Abkhaz business circles.

Overall, the legal framework protecting Russian investments is said to be faulty (for instance, the two countries do not recognize decisions made in the other county’s arbitration courts) (Aleksandrov and Papaskiri Citation2017). A major damper on investment has also been the Abkhaz refusal to allow foreigners to buy real estate in Abkhazia. Russians are free to invest in commercial enterprises, but the Abkhaz authorities have remained – to great Russian frustration – unswerving as regards real estate (Kolossov and O’Loughlin Citation2011, 640). This legal barrier can be circumvented by going through local frontmen, but that may prove risky (Kolstø Citation2020).

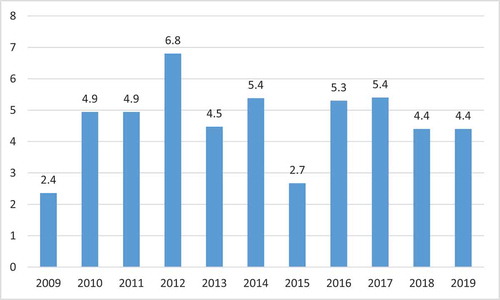

Thus, economic relations and mutual trust have not developed as might have been expected. According to one Russian view, “Russia’s main interest is to create and establish a sovereign, self-sufficient, and self-developing economy in Abkhazia that is receptive to Russian economic initiatives and focuses primarily on Russian markets” (Belyakov Citation2016). In Moscow, however, there is a growing feeling that Sukhumi is unwilling to adhere to the basic rules of business cooperation and that the Abkhaz show lack of gratitude for Russia’s recognition, security guarantees, and economic support.Footnote14 In addition, there have been numerous accusations of misappropriation, corruption, and nepotism in connection with the disbursement of Russian assistance (see, e.g., Kozlovskii Citation2017). Combined with Russia’s own post-2014 economic problems – sanctions, oil prices, the de facto devaluation of the ruble, and now the Covid-19 pandemic – this has made Russia less keen on bankrolling Sukhumi. Direct transfers to the Abkhaz state budget have been reduced (see ), and Russian authorities have essentially advised Russian businesses to look for opportunities elsewhere.Footnote15

Figure 1. Russian assistance to Abkhazia (in billion rubles)

The Abkhaz authorities face a difficult dilemma: on the one hand, Russia represents an enormous market, virtually the only possibility for engaging in official trade, and a source of potential investment in the Abkhaz economy. However, contrary to what we might have expected, this economic interaction does not necessarily translate into high levels of trust. From Sukhumi’s perspective, the asymmetry in size and economic power means that there is always the risk that the Abkhaz economy – and the state itself – may simply be absorbed into Russia, or at the very minimum, that Russian firms might monopolize large swaths of the most lucrative businesses. Sukhumi sees no real alternative to Russia today, but it still tries to keep the patron at arm’s length, even if to the detriment of its own economic and socio-economic development.

Trade and economic relations with the parent state

The starting point for Abkhazia’s postwar economic interaction with Georgia proper was hardly the best: the war had fanned animosity and ethnic hatred across the de facto border (also referred to as the “administrative boundary line,” ABL) and severed long-standing networks of trade and economic interaction. Both the Abkhaz and Georgian economies were in shambles – and the level of trust among old neighbors at a low point.Footnote16

Despite the desperate economic situation during the early postwar years, the de facto state authorities were not ready to resume official trade or economic cooperation with Georgia proper.Footnote17 The tense situation was exacerbated by the de facto state authorities’ tenuous control over the Gali District bordering the ABL and populated almost exclusively by ethnic Georgians. Here paramilitary forces operated with Georgian backing up until the early 2000s, openly challenging the authority of Sukhumi. Due to lack of state capacity, the de facto state authorities opted for isolating rather than integrating this region into the rest of Abkhazia, in practice quietly accepting their inability to control the flows of goods and people across the ABL (Prelz Oltramonti Citation2016, 248).

From around the turn of the millennium, the economic and security situation began to improve. Greater state capacity did not soften the official Abkhaz stance on trade with Georgia, however: if anything, Sukhumi became even more intransigent. After the 2008 Russo–Georgian War, the Abkhaz were, with the assistance of Russian border guards, able to introduce better control along the ABL. With the border with Russia opening up for increased economic interaction, Sukhumi had both the opportunity and the means to clamp down on trade across the ABL. According to a presidential decree adopted in 2007 and still in effect, all commercial goods crossing the ABL into Abkhazia are officially considered contraband (Mirimanova Citation2013, 3–4). Similarly, Sukhumi does not allow Abkhaz businesses to trade with Georgia proper – the only exception being hazelnuts, a major Abkhaz cash crop, legalized in 2015 (Zavodskaya Citation2016). Moreover, the de facto state authorities in 2017 closed down all but two of the border crossings with Georgia proper – and also the remaining ones have been temporarily suspended for extended periods.Footnote18

The restrictive Abkhaz attitude was paralleled in the Georgian approach. To be sure, given Tbilisi’s understanding of Abkhazia as being an integral part of Georgian territory, temporarily outside the central government’s control, cross-ABL trade is in principle understood as internal trade (Mirimanova Citation2013, 3). From a security perspective, however, trade and other economic interaction with the de facto state are seen as helping to bolster the Abkhaz authorities’ grip on power. Tbilisi therefore lobbied for the introduction of the CIS embargo implemented in 1996, banning all economic, financial, transport, and other state-level interactions with Abkhazia without prior authorization from the Georgian government. According to a former Georgian official, the dominant view in Tbilisi was to “squeeze the Abkhaz till they capitulate and crawl back to Georgia” (quoted in de Waal Citation2018, 23).

In 2003, the Rose Revolution brought regime change in Tbilisi, and with it, a new take on relations with the breakaway entities. The new president, Mikheil Saakashvili (2004–2013), sought to step up the pressure on the de facto state authorities. Believing that if the economic sources were to dry up, Sukhumi would be forced to negotiate, Saakashvili tried to stem the smuggling and reduce the overall trade volumes with Abkhazia (Gotsiridze Citation2004; Prelz Oltramonti Citation2017).

However, the watershed in cross-ABL economic interaction came in the wake of the 2008 Russo–Georgian war. In response to Russian recognition of Abkhaz independence, Tbilisi officially declared the territory as “occupied by Russia.” In October 2008, the Georgian Parliament adopted a law “On Occupied Territories,” introducing a “special legal regime” which, inter alia, prohibited

any economic (entrepreneurial or non-entrepreneurial) activity, irrespective of whether it is carried out to gain profit, income or compensation, if an appropriate license or a permit, authorization or registration is required to conduct this activity under the Laws of Georgia (Legislative Herald of Georgia Citation2008).

Georgia does not recognize any paperwork issued by the Abkhaz de facto authorities – therefore, no goods produced in Abkhazia can legally access the Georgian market. The law also specifies that any actor wishing to invest in Abkhazia or to transport goods through Abkhazia to Russia must first obtain approval from the Georgian government. However, since the adoption of this law, no company engaged in trade has applied for such a permit (ICG Citation2018, 10). In cases where international companies have tried to circumvent the law, Georgia has responded with sanctions. One instance concerned the Italian fashion company Benetton, whose Turkish subsidiary in 2009 wanted to open a local store in Sukhumi. After protests in front of the Turkish Embassy in Georgia and the Georgian Ministry of Foreign Affairs summoning the Turkish ambassador, calling the plans to open the shop “outrageous,” Benetton abandoned the idea (Ó Beacháin, Comai, and Tsurtsumia-Zurabashvili Citation2016, 454). Four years later, it was McDonald’s turn, forced by “aggressive diplomatic measures” (ibid.) to drop its plans for a restaurant in Sukhumi.

However, this policy of applying sticks against international businesses has since 2010 been accompanied by offering some carrots to the Abkhaz. The 2010 State Strategy on Occupied Territories declares Georgia’s aim to be “engagement through cooperation” (Office of the State Minister … Citation2010). The strategy aims at winning the hearts and minds of the Abkhaz population – and thereby its trust – by giving them access to services and benefits in Georgia proper.Footnote19 One suggested measure involved finding “legal solutions to enable and encourage the sale of products from Abkhazia and the Tskhinvali region/South Ossetia to domestic, regional, and international markets” (ibid., 9). Due to Georgia’s firm stance on the status issue, however, this initiative was not welcomed by the Abkhaz side (Kereselidze Citation2015, 316) and thus gained little traction.

In 2018 the Georgian Dream government unveiled an ambitious new initiative, “A Step to a Better Future.” Also this policy initiative was based on the idea of building trust through engagement, focusing on enhanced opportunities for education and economic interaction. The Georgian authorities pledge to “facilitate trade across dividing lines with the aim of improving the humanitarian and socio-economic conditions of the population living in Abkhazia,” including new access to internal (Georgian) and external markets (Office of the State Minister … Citation2018). Again, Sukhumi’s official reaction has been lukewarm.Footnote20 Abkhazia’s Minister of Foreign Affairs Daur Kove declared:

The Republic of Abkhazia is an independent, sovereign state. The only step in [sic] a better future is Georgia’s recognition of the independence of the Republic of Abkhazia and the construction of a full-fledged interstate dialogue between our countries in order to [foster] stability and prosperity for future generations. There is no alternative to this process (Ministry of Foreign Affairs … Citation2018).

Given the profound distrust between Georgian and Abkhaz authorities and the legal restrictions on trade, limited economic interaction was to be expected. However, as noted in a recent ICG report on the Georgian–Abkhaz conflict, “laws do not stop trade across the conflict divides; they simply shove it into the shadows” (ICG Citation2018, 11). Despite the deep mistrust between Sukhumi and Tbilisi and the various attempts by both parties to introduce tighter controls over the flow of commercial goods, informal cross-ABL trade has been a constant feature ever since the conclusion of the 1994 ceasefire agreement. During the embargo years, this cross-ABL trade offered an important lifeline, enabling the much-needed supply of essential goods to the Abkhaz market (Prelz Oltramonti Citation2015, 299) – with scrap-metal, counterfeit brand-name cigarettes, and fuel flowing in the opposite direction (Gotsiridze Citation2004). Until the 2008 war, corruption and lack of physical control rendered the ABL porous to small-scale trade, as it was relatively easy to cross the river on foot or by car (Prelz Oltramonti Citation2016, 255).

Even after 2008, despite the new legislation introduced by Tbilisi and Sukhumi, as well as better Abkhaz capacity to control the ABL, the informal trade continued. While hazelnuts are officially the only product the Abkhaz allow to be exported, and the Georgian side formally accepts only merchandise in compliance with the Law on Occupied Territories, unregulated cross-ABL trade has thrived: according to a recent ICG report, Abkhaz authorities reported an estimated 150 tons of commercial cargo moving in and out across the ABL every day, with an annual value of 7 to 15 million USD (ICG Citation2018, 8).Footnote21

This trade is asymmetric, the flow going mostly from Georgia to Abkhazia. According to a 2012–2013 survey, informal trade was largely centered on foodstuffs and furniture (Mirimanova Citation2013, 5). At the time, an estimated 25–40% of certain types of basic agricultural products and household goods on the Abkhaz market came from Georgia proper (ibid.). From the Abkhaz side, the informal trade has mainly involved hazelnuts, citruses, and fruit sold on the Georgian market or (re-)exported to Armenia and Azerbaijan and beyond (ibid., 4; ICG Citation2018, 8).

Despite Abkhaz households’ dependence on imported Georgian goods,Footnote22 as well as widespread acceptance in Georgia proper for doing business with Abkhazia (in recent years, approval has hovered above 70%) (CRRC Citation2019), the vibrant informal trade has not led to public pressure to change the restrictive policies in both entities. In other words, even if informal trade contributes to trust on the societal level, it does not necessarily contribute to trust at the state level.Footnote23 The various overtures made by official Tbilisi as to economic engagement have gained little traction. Sukhumi has denounced these initiatives as being one-sided and not to the benefit of Abkhazia.Footnote24 Thus, even though we find more economic interaction than expected, political sensitivities reign supreme and mutual trust remains low. The Georgian and Abkhaz authorities are cautious about taking any step that could be perceived as a compromise on the status issue, since this is highly likely to backfire at home, triggering protests from the opposition and the general public alike. In these relations, status and lack of trust trump trade, even if trade would be mutually advantageous.

Trade and economic relations with the outside world: the EU

Due to its lack of international recognition, Abkhazia’s possibilities for developing trade relations with the outside world beyond the patron and, potentially, the parent state are severely circumscribed. Still, given Sukhumi’s wariness of ending up too deep in the Russian economic embrace as well as its unwillingness to realize the possible benefits of formalizing trade with Georgia proper, the Abkhaz authorities have been looking for ways to diversify trade and economic relations beyond patron and parent. Thus far, most success has been achieved with Turkey. Officially, Turkey still adheres to the 1996 embargo (Zabanova Citation2016), but members of the Abkhaz diaspora in Turkey have been active in their advocacy of Abkhaz interests, and have engaged in business operations with their ethnic kin (Punsmann Citation2009; Frear Citation2014). However, this unofficial trade has proved vulnerable to the ups and downs in Turko–Russian relations. In 2015, Moscow forced Abkhazia to introduce temporary sanctions in its trade with Turkey after the latter had downed a Russian jet in Syria (Zabanova Citation2016, 12).Footnote25 Hence, diversifying trade and gaining access to other markets and suppliers in Europe and beyond have now become more of a priority.

That has not always been the case. Abkhaz authorities have long been distrustful of the EU, seeing it as openly pro-Georgian and with scant sympathy for the Abkhaz cause. As for the EU, prior to 2008, it did not seriously engage in the South Caucasian secessionist conflicts, limiting itself largely to declaratory statements (Kereselidze Citation2015, 312).Footnote26 However, the 2008 war and Russia’s subsequent recognition of Abkhazia changed EU priorities in the region, prompting a new focus on the geopolitical realities around the secessionist conflicts.

During the active phase of the war, the EU chairmanship was instrumental in brokering a ceasefire. After the cessation of hostilities, Brussels assisted in setting up the Geneva International Discussions (the main forum for dealing with the outcome of the August war) and dispatched an official EU Monitoring Mission (EUMM) to Georgia. As for trade, in December 2009, the EU adopted a “Non-Recognition and Engagement Policy” (NREP) with a new strategy for engaging with the secessionist entities, including “economic interaction across conflict lines” (Fischer Citation2010, 1). The EU’s new approach was “premised on the understanding that isolation only pushes the breakaway entities closer to Russia and solidifies their negative attitudes towards Georgia and the West” (Weiss and Zabanova Citation2016, 9). The NREP was intended to open “a political and legal space in which the EU can interact with the separatist regions without compromising its adherence to Georgia’s territorial integrity” (Fischer Citation2010, 1). While seeking to facilitate the de-isolation of Abkhazia, the EU took care to reassure the Georgian authorities that international engagement with Abkhazia was not a step toward “creeping recognition” or the “de facto sovereignty” of this territory.

Although the EU’s post-2008 approach has been described as “modestly successful” (de Waal Citation2017a), it has arguably fared better as regards nonrecognition than meaningful engagement. Within the NREP framework, the EU has contributed nearly 50 million Euros to projects involving Abkhaz partners (de Waal Citation2017b).Footnote27 Overall, however, the results have fallen short of expectations. One reason is that the Abkhaz side has not demonstrated a capacity to capitalize on the EU initiatives:Footnote28 indeed, the Abkhaz authorities have been accused of being passive recipients. According to an analytical report published on the website of the Abkhaz Ministry for Foreign Affairs:

the Abkhaz side itself does not show any initiative, does not come up with concrete ideas for cooperation, does not sufficiently inform EU officials about its problems and aspirations or engage in promoting Abkhazia’s interests in the West (Ministry of Foreign Affairs … Citation2012).

Another reason is Georgian skepticism. Georgia’s Law on Occupied Territories severely circumscribes the range of avenues available for engaging the de facto state authorities. Moreover, despite Georgia’s own official engagement policy, Tbilisi has tended to distrust the motivation of any international engagement efforts, interpreting these as playing into the hands of Moscow. This was especially true during the heyday of the United National Movement rule and Mikheil Saakashvili’s presidency, whereas the Georgian Dream government (in power since 2012) has adopted a somewhat more permissive attitude toward international engagement (de Waal Citation2017a).

Finally, any EU initiatives have been dwarfed by Moscow’s growing assertiveness. The Russian presence is ubiquitous throughout the republic, and investments have been generous. According to some estimates, Russia has spent more than ten times as much on pensions alone as the whole contribution from the EU (de Waal Citation2018, 26). The EU has become basically invisible on the ground.

Most ordinary Abkhaz remain unaware of the EU’s investments. Whereas in Georgia proper, the EU is perceived as a neutral mediator, in Abkhazia the deep-rooted discourse about Abkhazia as the undeserving victim of an EU policy of isolation remains dominant. However, Delcour and Wolczuk (Citation2018, 58–59) note a certain shift in public attitudes:

even though suspicious about an increased EU involvement in conflict resolution, citizens of Abkhazia (…) regard the development of ties with the EU as highly desirable for their region. This is because they view the EU as (…) an important partner to balance Russia.

Indeed, observers have pointed out that official Abkhaz resentment toward the EU’s “engagement without recognition” seems to have softened, due to the growing resistance among some segments of the public and the political elite alike to “Russia’s over-dominance” (Gaprindashvili et al. Citation2019, 7). Lacking trust in Moscow’s designs, many Abkhaz fear that the de facto state may ultimately succumb to what some refer to as “Ossetianization” – de facto absorption into Russia (de Waal Citation2018, 24).Footnote29 Looking for alternatives and expanding Abkhazia’s economic options have thus become “a necessity rather than a luxury” (Gaprindashvili et al. Citation2019, 15; see also ICG Citation2018, 10).

Given the formal legal constraints related to status, the only feasible way for Abkhaz businesses to access European markets directly would be through being included in Georgia’s Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (DCFTA) with the EU. For obvious reasons, this agreement, which entered into force in 2016, did not include economic activity on the territory under Sukhumi’s control.Footnote30 In 2017, however, the EU started exploring possibilities for extending the DCFTA to include Abkhaz businesses.Footnote31 Over the next months, Brussels engaged in a cautious, “quiet” diplomacy, with EU representatives visiting Abkhazia twice to discuss the details of the DCFTA, and the EU expressing its readiness to facilitate direct talks between the Abkhaz and Georgian sides (ICG Citation2018, 17). The EU initiative gave an impetus to discussions about the prospects for resuming formal trade links between Sukhumi and Tbilisi. As yet, however, this has failed to move beyond the exploratory phase. Again, the stumbling block is status. Sukhumi welcomed the EU proposal to extend DCFTA benefits to Abkhazia – but, for this to happen, Georgia would first, according to the head of Abkhazia’s Chamber of Commerce, former Prime Minister Gennadii Gagulia, have to recognize Abkhazia’s independence (de Waal Citation2018, 30).

In the absence of formal access, Abkhaz businesses have had to rely on Russian and Georgian middlemen – a practice said to double, even triple, the cost of doing business (ICG Citation2018, 10). According to the ICG, Abkhaz businesses “have quietly sought partnerships with European companies ready to accept either Georgian or Russian customs codes for shipping”; companies in more than a dozen EU states are said to be involved in such trade (ibid.). According to official Abkhaz trade statistics, the most important partner among the EU countries is currently Italy (Sputnik Citation2020). This trade is potentially highly profitable. Imported goods from Europe tend to be cheaper; as for exports, Abkhaz hazelnuts reportedly may fetch a price five times higher than on the Russian market (ICG Citation2018, 11). However, the reliance on middlemen complicates matters. According to a local economic analyst, “Trade with the West is possible, but with too many headaches” (quoted in ICG Citation2018, 10).

In addition, Russia as a patron has not necessarily welcomed Abkhaz attempts to branch out and seek investment and technologies from EU-based companies rather than from Russian counterparts. One example is the 2016 attempt of the Sukhumi city government to explore possibilities for developing a “smart city” scheme in the Abkhaz capital. To that end, they concluded a contract with a Czech supplier. Moscow did not approve, however. In the words of Russian economist Sergei Belyakov (Citation2016), in choosing a key partner among several possibilities, “Russia and Abkhazia should give preference to each other”. In the end, plans for a “smart city” never got off the drawing board. However, the resentment expressed toward the idea of bringing in a Czech partner is illustrative. Given the indispensable political and economic support it gives to Abkhazia, Moscow believes it is entitled to a certain droit de regard in Abkhazia’s relations with the outside world (Kolstø Citation2020).

Ultimately, though, it is the status question, not Russian interference, that acts as the main restraint on developing trade with the EU. In Sukhumi, the authorities are guided by “stubborn pride,” insisting that what they need is “international recognition – and nothing else” (de Waal Citation2017b); they are not ready to compromise in order to get access to the EU market. And in Brussels, the failure to get discussions started on a potential extension of the DCFTA to Abkhaz businesses has allegedly led to a certain Abkhazia fatigue (Gaprindashvili et al. Citation2019, 10). The status question continues to block a major breakthrough in direct trade as well as investment in the Abkhaz economy. Levels of trade (Sputnik Citation2020) as well as trust (Delcour and Wolczuk Citation2018) remain low.

Conclusions

The 2008 Russian recognition settled some of the most pressing issues related to the immediate survival of the Abkhaz de facto state. However, in return for this important international breakthrough, Sukhumi saw its room for independent maneuver shrink even further. The price for Russian recognition has been “greater international isolation and de facto integration with Russia” (de Waal Citation2018, 20). The Abkhaz authorities declare themselves guided by two principles in their foreign relations: mnogovektornost’ (multi-vectoralism) and prioritetnost’ (prioritization). However, whenever these two principles have clashed, attempts to diversify along multiple vectors have proven secondary to the “Russia first” policy. This was clearly illustrated by the way Sukhumi responded to Russia’s demands for introducing sanctions on trade with Turkey in 2015. The Abkhaz authorities would not risk their relationship with the patron even if this meant potentially jeopardizing economic ties with their second-largest trading partner, Turkey.

As for the Georgian vector, thus far the Abkhaz authorities have chosen to forfeit the opportunity to diversify through formalizing the existing trade across the ABL. Russian patronhood has led to a certain hubris in Sukhumi. For example, Abkhazia’s Minister of Foreign Affairs Daur Kove bluntly dismissed the idea of engaging with Tbilisi, claiming that “Georgians don’t understand one simple thing. We don’t need them. We have survived 25 years without them’” (quoted in de Waal Citation2017b). Even so, according to the ICG (Citation2018), the volume of informal trade between Abkhazia and Georgia proper has been growing.Footnote32 And despite extreme wariness as to taking any steps that might be interpreted as undermining Abkhazia’s bid for independence, there seems, at least from 2014 onwards, to be a growing realization of the advantages of diversifying.Footnote33 According to the ICG, “In a departure from the past, [Abkhaz] stakeholders are quietly considering options for formalising aspects of trade” (ibid., i). In 2018 President Raul Khajimba (2014–2020) even aired the possibility of legalizing trade across the ABL (Abkhazia-Inform Citation2018), arguing the need to protect local businesses by introducing tariffs (although a new stream of revenues to the state coffers would undoubtedly be a welcome side-effect). Aslan Bzhania (Citation2020), Khajimba’s successor, in an interview with Georgian media (in itself a first in recent Abkhaz–Georgian relations) called for dialog between Sukhumi and Tbilisi and building trust through trade and economic interaction (InterPressNews Citation2020). As yet, however, nothing concrete has come of these overtures.

Trade with countries outside the region, including the EU, has been growing, but volumes remain limited (ICG Citation2018). While the main obstacle to formalizing trade along the Georgian vector has been the lack of political will, it is primarily legal constraints that prevent development along the EU vector, with Brussels standing firm on the principle of nonrecognition. In the coming years, trade with the EU – mainly imports – is likely to continue to increase, but this growth will require working with middlemen in Russia or Georgia proper.

To what extent could Abkhazia change its policy along one of the latter two vectors without risking accusations of turning its back on Russia? In fact, it might be in Moscow’s interest to encourage Abkhazia to develop trade and economic interaction with the outside world, as this would ease Russia’s financial burden – the dependence on Russian security guarantees would anyway ensure that Abkhazia remained safely in the fold. Moscow has, however, not necessarily welcomed Sukhumi’s attempts to diversify. The main obstacle to more diversified trade nevertheless seems to be the Abkhaz “obsession” with the status issue. For the Abkhaz, independence is non-negotiable. Status trumps trade.

How does trust factor in? While the conflict transformation literature highlights the interrelationship between trust and trade, the discussion above shows that in the case of Abkhazia there seems to be little correlation between the two: trust is surprisingly low between Abkhazia and its patron Russia – Abkhazia’s largest trading partner by far. Why is this so? Many Abkhaz feel that Russia is exploiting political patronage to dominate Abkhazia economically and push integration on Russian terms. They see Moscow as expecting a degree of gratitude and deference that they are not necessarily willing to extend. Some also recall when Russia turned its back on Abkhazia in the 1990s, as well as the brutal treatment of the Abkhaz by the Russian Empire (see Kolstø Citation2020) and ask whether Russia can be trusted if push comes to shove. As Thomas de Waal (Citation2010) observes, the Abkhaz “are pro-Russian much more by necessity than by natural enthusiasm”. Moreover, the fundamental asymmetry in size and power that characterize Russo–Abkhaz interactions, combined with the Abkhaz self-understanding of the nation as balancing on the brink of physical extinction (Kolstø and Blakkisrud Citation2008), contribute to Abkhaz insecurity and thus lack of trust. While Moscow may interpret Sukhumi’s stubborn defense of various symbolic aspects of statehood as an expression of disloyalty, Sukhumi feels squeezed in Moscow’s increasingly tight embrace. Despite the close economic integration, there is a strong undercurrent of mutual suspicion as to motivations and intensions.

As for Georgia proper, official relations are, as expected, marked by profound distrust. However, despite all the grievances and suspicion that permeate relations between Sukhumi and Tbilisi, we find far more economic interaction than expected: ever since the war of secession, the ABL has seen a steady flow of (illegal) trade. However, as long as this trade remains a shadowy affair, any societal trust that might exist in the immediate cross-border region does not contribute to greater trust at state level. Official distrust does not prevent local trade, but there is no feedback loop influencing trust at the state level.

Finally, as regards the EU, the picture is basically as we expected: trust and trade remain low. Trade is expected to evolve, but the need to work through middlemen is not conducive to developing trust: producers and their markets do not interact directly.

Our findings indicate that, with de facto states, the correlation between trade and trust, and thereby between trade and conflict transformation, may be more complex than often assumed. In the absence of formal recognition, trade does not necessarily promote trust. In the case of Abkhazia, we have observed how not only rational economic and political facts, but also emotional aspects related to memory and self-understanding factor in. The unresolved status issue combined with an acute sense of uncertainty about the nation’s future have led Abkhazia’s trade relations along all three vectors to be characterized by deep distrust. Trade is not followed by trust. There is a recognized need to diversify, but little appetite for the compromises needed to achieve this.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. To distinguish such unrecognized secessionist entities from more short-lived separatist conflicts, we, drawing on Pål Kolstø’s definition (Citation2006, 749–50) define a de facto state as an entity that 1) is in control of a substantial part of the territory it lays claim to; 2) has sought international recognition as an independent state; 3) has achieved recognition by less than ten UN member-states; and 4) has existed for at least two years.

2. This article draws on fieldwork and more than 25 in-depth, semi-structured interviews on Abkhaz foreign trade relations/trust with politicians, diplomats, bureaucrats, journalists, NGO representatives and academics in Brussels (June 2016), Moscow (December 2017), Sukhumi (August 2018), and Tbilisi (November 2018 and January–February 2019). Interviews lasted from 45 minutes to one hour and were conducted in English, Russian, or Georgian. The selection of interviewees was based partly on potential interlocutors being identified and approached prior to the fieldwork, partly on “snowballing” on location.

3. Abkhazian toponyms are contested. We have opted for the versions generally accepted as standard in English usage.

4. After two failed rebellions against Czarist Russia in 1866 and 1877, several hundred thousand ethnic Abkhaz fled/were deported to the Ottoman Empire. Today there are an estimated 500,000 Abkhaz in Turkey (Zabanova Citation2016). In the early 1990s, these members of the diaspora were among the very few to trade with Abkhazia.

5. Given the nature of Abkhaz trade, all such figures should be treated cautiously. As noted by Giulia Prelz Oltramonti, analyzing the Abkhaz economy entails many challenges: “little literature exists, official statistics are unreliable and controversies are always a few steps away” (Prelz Oltramonti, 2015, 291).

6. During the Soviet period, ethnic Abkhaz became a minority within their own “national republic” (by 1991, they constituted only 17.8% of the population). This experience has engendered considerable ethnic sensitivity around questions like citizenship, return of IDPs, and migration.

7. Abkhazia is currently recognized by five UN members: the Russian Federation, Nauru, Nicaragua, Syria, and Venezuela.

8. Russia is followed by Turkey with 8%. The remaining 22% is made up by trade with over 40 other countries (see Sputnik Citation2020).

9. While Abkhazia has introduced an official currency, apsar, this move is mainly symbolic: all transactions are conducted in Russian rubles.

10. In 2020, due to Covid-19, the Abkhaz–Russian border was closed throughout much of the summer, re-opening on August 1. The number of tourists was therefore expected to drop 30–50% (Ryzhkov Citation2020).

11. According to the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, as of 2017, there were 241 joint ventures and 237 enterprises with 100% Russian capital operating in Abkhazia (Konsul’skiy informatsionnyy portal Citationn.d.).

12. Authors’ interviews, Sukhumi, August 2018.

13. The forced resignation of President Aleksandr Ankvab (2011–2014) the previous year had paved the way for a redistribution of assets, with Ankvab being replaced by opposition leader Raul Khajimba (2014–2020).

14. Authors’ interviews, Moscow, December 2017.

15. Authors’ interviews, Sukhumi, August 2018.

16. In addition, the ethnic cleansing in the last phase of the war resulted in a large IDP community in Georgia proper – according to some estimates, 190,000–240,000 ethnic Georgians fled Abkhazia (Kolossov and O’Loughlin Citation2011, 633). This had negative impacts on the Abkhaz economy (workforce drain) and the prospects of a negotiated solution, with the IDP population serving as a constant reminder of injustice.

17. The exception is the Inguri Power Plant, straddling the ABL (the dam is located in Georgia proper; the generators are situated on the Abkhaz side). Here the Abkhaz authorities have cooperated with Tbilisi in generating hydroelectric power ever since the end of the 1992–1993 war; the power plant supplies Western Georgia and Abkhazia alike.

18. In 2020, due to the Covid-19 pandemic, Abkhaz authorities closed the border. Since then, the crossing point at Inguri has been open for only a few days every month.

19. Authors’ interview with Georgian official, Tbilisi, January 2019.

20. Authors’ interviews, Sukhumi, August 2018.

21. These are rough estimates, as Abkhaz trade statistics are frequently unreliable – and it is even more difficult to produce precise estimates on the informal trade across the ABL.

22. With the depreciation of the Russian ruble, the purchasing power of ordinary Abkhaz has decreased, and the demand for cheap Georgian products has risen (authors’ interviews, Sukhumi, August 2018).

23. Although we lack data on popular trust in parent-state authorities, John O’Loughlin and colleagues find that close to 40% of the ethnic Abkhaz harbor “very good” or “good” feelings toward the parent-state population (O’Loughlin, Kolossov, and Toal Citation2014, 447). This stands in stark contrast to the official attitudes espoused by the de facto state authorities.

24. Authors’ interviews, Sukhumi, August 2018.

25. Whereas such sanctions would have no effect on Turkey, they would have very negative consequences for the Abkhaz economy: at the time, Turkey accounted for some 18% of Abkhazia’s total trade turnover, making it Abkhazia’s second biggest trading partner after Russia (Weiss and Zabanova Citation2016, 2). In the end, however, the sanctions regime was so designed as to minimize its negative impact on Abkhaz economy.

26. In 2003, the EU had appointed a Special Representative to assist Georgia in its economic and political reform as well as in resolving the secessionist conflicts – but the appointment “received little political attention in both Brussels and Tbilisi” (Kereselidze Citation2015, 312).

27. EU-funded projects include supporting local NGOs, improving healthcare and education, repairing water facilities, rebuilding houses in the Gali District, and locating and exhuming victims of the 1992–1993 war for reburial.

28. In Brussels, our interlocutors also mentioned lack of knowledge as a reason for why the Abkhaz were not able to utilize the available opportunities fully (interview, Brussels, June 2016).

29. Whereas the Abkhaz elite fight fiercely for official recognition of independence, the main goal for the South Ossetian elite has been reunification with ethnic brethren in North Ossetia, and it therefore pushes for joining the Russian Federation.

30. Interview with EU official, Brussels, June 2016.

31. A precedent had been set in another post-Soviet secessionist conflict, that between Moldova and Transnistria, where the two conflicting sides agreed in 2015 to trade with the EU being regulated by Moldova’s DCFTA. However, experts in Brussels and Tbilisi noted that this experience was not necessarily transferable to the very different case of Abkhazia (interview with EU official, Brussels, June 2016, see also Delcour and Wolczuk Citation2018; Kemoklidze and Wolff Citation2020).

32. This trade was temporary suspended when in 2020 the border was closed due to Covid-19. Tightened control on the Abkhaz side may, however, have a negative effect on the prospects for continued growth in a post-pandemic setting.

33. Authors’ interviews, Sukhumi, August 2018.

References

- Abkhazia-Inform. 2018. “Prezident Raul’ Khadzhimba Vystupayet za Legalizatsiyu Torgovli na Granitses Gruziei” [President Raul Khajimba Promotes Legalization of Trade at the Border with Georgia]. August 30. Accessed February 5, 2020. http://abkhazinform.com/item/7746-prezident-raul-khadzhimba-vystupaet-za-legalizatsiyu-torgovli-na-granitse-s-gruziej

- Ademmer, E., L. Delcour, and K. Wolczuk. 2016. “Beyond Geopolitics: Exploring the Impact of the EU and Russia in the “contested Neighborhood”.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 57 (1): 1–18.

- Agumova, F. 2018. “Abkhaziya, Eto Russkaya Gavana” [Abkhazia—that Is Russian Havana!]. Parlamentskaya gazeta, August 28. Accessed October 23, 2019. https://www.pnp.ru/politics/abkhaziya-eto-russkaya-gavana.html

- Akaba, N., and I. Gitsba. 2011. “Abkhazia’s Isolation/de-isolation and the Transformation of the Georgian–Abkhaz Conflict: A Historical Political Analysis.” In The De-isolation of Abkhazia. London: International Alert.

- Aleksandrov, I., and O. Papaskiri. 2017. “Problemy Pravovogo Regulirovaniya Abkhazo-rossiyskikh Otnosheniy vInvestitsionnom Kontekste” [The Problems of Legal Regulation of Abkhaz–Russian Relations in the Context of Investments]. Accessed October 20, 2019. https://zakon.ru/blog/2017/5/10/problemy_pravovogo_regulirovaniyaabhazo-rossijskih_otnoshenijv_investicionnom_kontekste

- Ambrosio, T., and W. Lange. 2016. “The Architecture of Annexation? Russia’s Bilateral Agreements with South Ossetia and Abkhazia.” Nationalities Papers 44 (5): 673–693.

- Anomaly, J. 2017. “Trust, Trade and Moral Progress: How Market Exchange Promotes Trustworthiness.” Social Philosophy & Policy 2: 89–107.

- Averre, D. 2009. “Competing Rationalities: Russia, the EU and the ‘Shared Neighbourhood’.” Europe–Asia Studies 61 (10): 1689–1713.

- ÓBeacháin, D., G. Comai, and A. Tsurtsumia-Zurabashvili. 2016. “The Secret Lives of Unrecognised States: Internal Dynamics, External Relations, and Counter-recognition Strategies.” Small Wars & Insurgencies 27 (3): 440–466.

- Belyakov, S. 2016. “Abkhazskiy Spros iRossiyskoe Predlozhenie” [Abkhaz Demand and Russian Supply]. Sputnik, October 27. Accessed October 21, 2019. https://sputnik-abkhazia.ru/analytics/20161027/1019751020/abxazskij-spros-i-rossijskoe-predlozhenie.html

- Blakkisrud, H., and P. Kolstø. 2012. “Dynamics of De Facto Statehood: The South Caucasian De Facto States between Secession and Sovereignty.” Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 12 (2): 281–298.

- Chablin, A., and A. Skakov. 2019. “Leto-2019: Rossiyanam Zapretyat Otdykhat’ vAbkhazii Iz-za Razgula Prestupnosti” [Summer of 2019: Russians Will Not Be Allowed to Vacation in Abkhazia Due to Rampant Crime]. Svobodnaya pressa, June 11. Accessed October 21, 2019. https://svpressa.ru/travel/article/235238/

- Comai, G. 2018. What Is the Effect of Non-Recognition? The External Relations of De Facto States in the Post-Soviet Space. PhD thesis, Dublin City University.

- Cooley, A., and L.A. Mitchell. 2010. “Engagement without Recognition: A New Strategy toward Abkhazia and Eurasia’s Unrecognized States.” The Washington Quarterly 33 (4): 59–73.

- CRRC. 2019. “Approval of Doing Business with Abkhazians.” Caucasus Barometer, October. Accessed November 23, 2020. https://caucasusbarometer.org/en/cb-ge/BUSINABK/

- de Waal, T. 2010. “The Ghosts of Abkhazia.” The National Interest, December 8. Accessed February 5, 2020. http://nationalinterest.org/commentary/the-ghosts-abkhazia-4531

- de Waal, T. 2017a. “Enhancing the EU’s Engagement with Separatist Territories.” Carnegie Europe, January 17. Accessed October 21, 2019. https://carnegieeurope.eu/2017/01/17/enhancing-eu-s-engagement-with-separatist-territories-pub-67694

- de Waal, T. 2017b. “Abkhazia: Still Isolated, Still Proud,” Carnegie Europe, October 30. Accessed January 16, 2020. https://carnegieeurope.eu/strategiceurope/73579

- de Waal, T. 2018. “Uncertain Future: Engaging with Europe’s De Facto States and Breakaway Territories.” Carnegie Europe. Accessed October 21, 2019. https://carnegieendowment.org/files/deWaal_UncertainGround_final.pdf

- Delcour, L. 2017. The EU and Russia in Their “Contested Neighbourhood”. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Delcour, L., and K. Wolczuk. 2018. “Well-Meaning but Ineffective? Perceptions of the EU’s Role as a Security Actor in the South Caucasus.” European Foreign Affairs Review 23 (1): 41–60.

- Dogovor. 2014. “Dogovor Mezhdu Rossiiskoi Federatsii Respublikoi Abkhaziya o Soyuznichestvei Strategicheskom Partnerstve” [Agreement between the Russian Federation and the Republic of Abkhazia on Alliance and Strategic Partnership]. Kremlin.ru, November 24. Accessed January 16, 2020. http://kremlin.ru/supplement/4783

- Dzhopua, R. 2015. “Blok Oppozitsionnykh Sil Abkhazii: Otkaz ot Dobychi Nefti ne Opravdan” [Block of Opposition Forces of Abkhazia: Cancellation of Oil Production Is Not Justified]. Sputnik, August 5. Accessed January 16, 2020. https://sputnik-abkhazia.ru/Abkhazia/20150805/1015383765.html

- Esiava, B. 2019. “Za Million: Chislo Turistov Abkhaziyu Vyroslo po Sravneniyus 2018 Godom” [Over a Million: The Number of Tourists to Abkhazia Has Increased Compared to 2018]. Sputnik, October 19. Accessed January 20, 2020. https://sputnik-abkhazia.ru/Abkhazia/20191021/1028660636/Perevalit-za-million-chislo-turistov-v-Abkhaziyu-vyroslo-na-10-v-2019-godu.html

- Evensky, J. 2011. “Adam Smith’s Essentials: On Trust, Faith, and Free Markets.” Journal of the History of Economic Thought 33 (2): 249–267.

- Fischer, S. 2010. “The EU’s Non-Recognition and Engagement Policy Towards Abkhazia and South Ossetia.” EUISS Seminar Reports. Accessed October 21, 2019. https://www.iss.europa.eu/sites/default/files/EUISSFiles/NREP_report.pdf

- Frear, T. 2014. “The Foreign Policy Options of a Small Unrecognised State: The Case of Abkhazia.” Caucasus Survey 1 (2): 83–107.

- Gaprindashvili, P., M. Tsitsikashvili, G. Zoidze, and V. Charaia. 2019. One Step Closer—Georgia, EU-Integration, and the Settlement of the Frozen Conflicts? Tbilisi: GRASS. Accessed October 25, 2019. https://www.ecfr.eu/page/-/GRASS_Research_Draft_19.02.2019.pdf.

- Gotsiridze, R. 2004. “Georgia: Conflict Regions and the Economy.” Central Asia and the Caucasus 1: 144–152.

- Hegre, H., J.R. Oneal, and B. Russett. 2010. “Trade Does Promote Peace: New Simultaneous Estimates of the Reciprocal Effects of Trade and Conflict.” Journal of Peace Research 47 (6): 763–774.

- Hoffman, A.M. 2002. “A Conceptualization of Trust in International Relations.” European Journal of International Relations 8 (3): 375–401.

- Hoffman, A.M. 2006. Building Trust: Overcoming Suspicion in International Conflict. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

- ICG. 2018. “Abkhazia and South Ossetia: Time to Talk Trade.” ICG Europe Report 249. Accessed October 21, 2019. https://d2071andvip0wj.cloudfront.net/249-abkhazia-and-south-ossetia-time-to-talk-trade (1).pdf

- Inal-Ipa, A., and A. Shakryl. 2011. “Ekspertnoe Mnenieo Perspektivakh Mezhdunarodnogo Priznaniya Abkhazii Roli Gruzii” [Expert Opinion on the Prospects for International Recognition of Abkhazia and Georgia’s Role]. In Politika Nepriznaniya vKontekste Gruzino-abkhazskogo Konflikta, 22–29. London: International Alert.

- InterPressNews. 2020. “Aslan Bzhania: There Should Be Dialogue between Sokhumi and Tbilisi.” January 16. Accessed November 18, 2020. https://www.interpressnews.ge/en/article/105387-aslan-bzhania-there-should-be-dialogue-between-sokhumi-and-tbilisi

- Jaksa, U. 2019. Interpreting Non-Recognition in De Facto States Engagement: The Case of Abkhazia’s Foreign Relations. PhD thesis, University of York.

- Kelman, H.C. 2005. “Building Trust among Enemies: The Central Challenge for International Conflict Resolution.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 29 (6): 639–650.

- Kemoklidze, N., and S. Wolff. 2020. “Trade as a Confidence-building Measure: Cases of Georgia and Moldova.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 61 (3): 305–332.

- Kereselidze, N. 2015. “The Engagement Policies of the European Union, Georgia and Russia Towards Abkhazia.” Caucasus Survey 3 (3): 309–322.

- Ker-Lindsay, J. 2012. The Foreign Policy of Counter Secession: Preventing the Recognition of Contested States. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kolossov, V., and J. O’Loughlin. 2011. “After the Wars in the South Caucasus State of Georgia: Economic Insecurities and Migration in the ‘De Facto’ States of Abkhazia and South Ossetia.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 52 (5): 631–654.

- Kolstø, P. 2006. “The Sustainability and Future of Unrecognized Quasi-states.” Journal of Peace Research 43 (6): 723–740.

- Kolstø, P. 2020. “Biting the Hand that Feeds Them? Abkhazia–Russia Client–Patron Relations.” Post-Soviet Affairs 36 (2): 140–158.

- Kolstø, P., and H. Blakkisrud. 2008. “Living with Non-recognition: State- and Nation-building in South Caucasian Quasi-states.” Europe–Asia Studies 60 (3): 483–509.

- Konsul’skiy informatsionnyy portal. n.d. “Abkhaziya.” [Abkhazia]. Accessed October 21, 2019. https://bit.ly/2BzKGmP

- Kozlovskii, S. 2017. “Skol’ko Deneg Rossiya Vydelyaet Abkhazii Kak ikh Tratyat” [How Much Money Does Russia Allocate to Abkhazia and How Do They Spend It]. BBC News,August 8. Accessed January 25, 2020. https://www.bbc.com/russian/features-40862115

- Kydd, A. H. 2005. Trust and Mistrust in International Relations. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Legislative Herald of Georgia. 2008. “Law of Georgia on Occupied Territories.” Accessed October 23, 2019. https://matsne.gov.ge/en/document/view/19132

- Ministerstvo Ekonomiki Respubliki Abkhaziya. 2017. “Podderzhka Eksportav Respublike Abhaziya na 2017–2019 Gody” [Export Support in the Republic in Abkhazia for 2017–2019]. Accessed October 21, 2019. http://mineconom-ra.org/ru/programmy/?ELEMENT_ID=635

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Abkhazia. 2012. Perceptions of the EU in Abkhazia and Prospects for the EU–Abkhazia Engagement: Analytical Report. Accessed January 13, 2020. http://old.mfaapsny.org/en/news_en/detail.php?ELEMENT_ID=1369

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Abkhazia. 2018. “The Commentary of Daur Kove on the New Peace Initiative of the Georgian Government ‘A Step to a Better Future’.” April 15. Accessed January 16, 2020. https://bit.ly/2Nyvqxd

- Mirimanova, N. 2013. Trans-Ingur/i Economic Relations: A Case for Regulation. London: International Alert. Accessed October 24, 2019. https://www.international-alert.org/sites/default/files/Caucasus_TransInguri_EconRelationsRegulation_EN_2013.pdf.

- Nordstrom, C. 2000. “Shadows and Sovereigns.” Theory, Culture & Society 17 (4): 35–54.

- O’Loughlin, J., V. Kolossov, and G. Toal. 2014. “Inside the Post-Soviet De Facto States: A Comparison of Attitudes in Abkhazia, Nagorny Karabakh, South Ossetia, and Transnistria.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 55 (5): 423–456.

- Office of the State Minister of Georgia for Reconciliation and Civic Equality. 2010. “State Strategy on Occupied Territories: Engagement through Cooperation.” Tbilisi. Accessed October 22, 2019. https://bit.ly/38IDPH4

- Office of the State Minister of Georgia for Reconciliation and Civic Equality. 2018. “‘A Step to a Better Future’: Peace Initiative. Facilitation of Trade across Dividing Lines.” Tbilisi. Accessed October 22, 2019. https://smr.gov.ge/uploads/prev/Concept_EN_0eaaac2e.pdf

- Prelz Oltramonti, G. 2015. “The Political Economy of a De Facto State: The Importance of Local Stakeholders in the Case of Abkhazia.” Caucasus Survey 3 (3): 291–308.

- Prelz Oltramonti, G. 2016. “Securing Disenfranchisement through Violence and Isolation: The Case of Georgians/Mingrelians in the District of Gali.” Conflict, Security and Development 16 (3): 245–262.

- Prelz Oltramonti, G. 2017. “Trajectories of Illegality and Informality in Conflict Protraction: The Abkhaz-Georgian Case.” Caucasus Survey 5 (1): 85–101.

- Punsmann, B. G. 2009. “Questioning the Embargo on Abkhazia: Turkey’s Role in Integrating into the Black Sea Region.” Turkish Policy Quarterly 8 (4): 77–78.

- Regnum. 2008. “‘Mnogovektornost” protiv ‘Prioritetnosti’: Abkhaziya za Nedelyu” [“Multi-vector” vs “Prioritization”: Abkhazia over the Week]. December 19. Accessed October 22, 2019. https://regnum.ru/news/polit/1101699.html

- RIA Novosti. 2018. “Adgur Ardzinba: Abkhazii Vse Tyazhelee Borot’sya za Turista” [Adgur Ardzinba: The Fight for Tourists Is Getting Harder for Abkhazia]. August 6. Accessed January 25, 2020. https://ria.ru/20180805/1525963428.html

- Rohner, D., M. Thoenig, and F. Zilibotti. 2013. “War Signals: A Theory of Trade, Trust, and Conflict.” Review of Economic Studies 80 (3): 1114–1147.

- Ryzhkov, L. 2020. “Turistov ne Ostanovit’” [Tourists Cannot Be Stopped]. Sputnik Abkhaziya, August 7. Accessed October 15, 2020. https://sputnik-abkhazia.ru/tourism/20200807/1030706509/Turistov-ne-ostanovit-chem-privlekaet-otdykh-v-Abkhazii.html

- Shariya, V. 2013. “Abkhaziyai Mnogovektornost’” [Abkhazia and Multi-vector Policy].Ekho Kavkaza, October 16. Accessed October 22, 2019. https://www.ekhokavkaza.com/a/25139088.html

- Soglashenie. 2012. Soglashenie mezhdu Pravitel’stvom Respubliki Abkhaziya i Pravitel’stvom Rossiiskoi Federatsii o Rezhime Torgovli Tovarami [Agreement between the Government of the Republic of Abkhazia and the Government of the Russian Federation on the Regime of Trade in Goods]. Accessed January 27, 2020. https://presidentofabkhazia.org/upload/iblock/9b9/z1.pdf

- Sputnik. 2018. “V Sukhume Podveli Itogi 10-letnego Sotrudnichestva Rossii Abkhazii” [Sukhumi Summed up the Results of 10 Years of Cooperation between Russia and Abkhazia]. October 12. Accessed January 22, 2020. https://sputnik-abkhazia.ru/press_release/20181012/1025275578/itogi-10-letnego-sotrudnichestva-rossii-abxazii.html

- Sputnik. 2020. “Plyus na Minus: Vneshnyaya Torgovlya Abkhaziiv 2019 Godu” [Plus to Minus: Foreign Trade of Abkhazia in 2019]. March 10. Accessed November 8, 2020. https://sputnik-abkhazia.ru/infographics/20200310/1029610168/Plyus-na-minus-vneshnyaya-torgovlya-Abkhazii-v-2019-godu.html

- Stateynov, D. 2019. “Yest' liv Abkhazii Neft’—i Pochemu Stol’ko Sporov Vokrug Proyekta ee Razvedki?” [Is There Oil in Abkhazia—and Why are There so Many Disagreements around Exploration?]. JAM news, February 3. Accessed October 22, 2019. https://bit.ly/2N4HRzE

- Weiss, A., and Y. Zabanova. 2016. “Georgia and Abkhazia Caught between Turkey and Russia: Turkey’s Changing Relations with Russia and the West in 2015–2016 and Their Impact on Georgia and Abkhazia.” SWP Comment 54/2016. Berlin: Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik.

- Wheeler, N.J. 2018. Trusting Enemies: Interpersonal Relationships in International Conflict. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Zabanova, Y. 2016. “Turkey’s Abkhaz Diaspora as an Intermediary between Turkish and Abkhaz Societies.” Caucasus Analytical Digest 86: 9–12.

- Zavodskaya, Y. 2016. “Nuzhna Inventarizatsiya Orekhovykh Plantatsiy” [An Inventory of Nut Plantations Is Needed]. Ekho Kavkaza, September 23. Accessed December 8, 2019. https://www.ekhokavkaza.com/a/28009471.html