ABSTRACT

The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) is a mega-project of primarily infrastructure-related loans and investments in Pakistan. Recently, the official discourse has increasingly shifted to the agricultural sector. For the region of Gilgit-Baltistan bordering China, academic and policy debates highlight the potential boost of fruit exports to China as the most promising opportunity to be leveraged through the CPEC. This paper scrutinizes these promises from a locally grounded perspective, investigating potential benefits and risks for local farmers. To make sense of the complex interplay between external and local actors, interests, markets and (infra)structures, the paper follows an assemblage-inspired approach to map out local trajectories. Contrary to the CPEC narrative, agricultural exports from Gilgit-Baltistan recently came to a halt, due to increasing trade barriers and seemingly competing agricultural developments in neighboring Xinjiang, China. Moreover, the economically most promising local crop for export to China, namely cherries, does not seem too promising for the majority of small farmers. There are other commodities with export potential, but overall, prospects appear to be limited. There is a need for a deeper engagement with the inherent complexities of CPEC trajectories, particularly in regards to local farming contexts in Pakistan and relevant developments in China.

Introduction

The mountain region of Gilgit-Baltistan is of key strategic importance for the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a collection of mainly infrastructure-related projects in Pakistan totaling about US$60 billion during the period 2015–2030 (McCartney Citation2020a; Wolf Citation2020). Bordering China’s western Xinjiang region, it serves as Pakistan’s northern gateway to the transport and investment corridor connecting Kashgar in Xinjiang to the deep-water seaport of Gwadar in Pakistan. However, concerns have been raised by local communities in Gilgit-Baltistan, who fear that CPEC investments primarily favor Pakistan’s economic centers in the Punjab, while the mountain area will merely serve as a transit region largely excluded from the promised benefits of intensified economic cooperation between the two countries (International Crisis Group Citation2018; Karrar Citation2019; Kreutzmann Citation2020).

Discussions about the CPEC’s prospects for the diverse regions of Pakistan have largely focused on infrastructure and industrial development. Meanwhile, a new sector has been announced as a new spotlight for upcoming CPEC investments: agriculture (CPEC Secretariat Citation2017; Husain Citation2017; State Bank of Pakistan Citation2018). As the official long-term plan reads, new CPEC projects shall “promote the transition from traditional agriculture to modern agriculture in the regions along the CPEC, to effectively boost the development of local agricultural economy and help local people get rid of poverty […]” (CPEC Secretariat Citation2017, 18). While no funds have officially been allocated to agricultural projects so far (Ahmad Citation2020), various policy papers and scholarly articles have outlined opportunities and proposed priorities for the CPEC in order to modernize production systems in Pakistan and to export a diversity of agricultural products to China (CDPR Citation2018; State Bank of Pakistan Citation2018; Ahmad Citation2017, Citation2020; Shafqat and Shahid Citation2018; Sher et al. Citation2019; Zulfiqar et al. Citation2019). Gilgit-Baltistan has received some special attention in this literature, with authors drawing a generally optimistic picture and highlighting the potential of the CPEC to boost the export of local fruits and fruit products to China (Ahmad Citation2017; Zulfiqar et al. Citation2019; Khalique, Ramayah, and Farooq Citation2020). Yet, there is little acknowledgment of the complexities of local farming systems and little consideration of actual developments on the ground to put these expectations into perspective. As illustrated herein, for local border communities, the transboundary trade of agricultural products has a long history but – contrary to the CPEC narrative – has recently declined. Moreover, the current literature neglects the local dynamics of farming systems. Consequently, a more nuanced knowledge of the local context is needed to evaluate not only opportunities, but also possible risks, for instance related to unequal market access and potential competition with agricultural imports from China.

This paper scrutinizes the promises of the CPEC in terms of agricultural development in Gilgit-Baltistan from a local perspective, focusing on the prospects of agricultural trade. Specifically, it asks: In what way will farming communities in Gilgit-Baltistan likely benefit from increased market access to China facilitated through CPEC-related activities? What are the opportunities and risks for local farmers, and who are the most probable beneficiaries?

To address these questions, I draw primarily on recent field research in Nagar District, located along the Karakoram Highway that connects Pakistan to China. Sometimes called the Pak-China Friendship Highway, this road crosses through the steep mountain environment of the Karakoram, thereby constituting the northern bottleneck of the CPEC transport corridor. While clear predictions on how the CPEC will shape local agrarian developments are impossible to make, I draw on assemblage thinking to sketch out and scrutinize possible trajectories based on past and present developments. For this purpose, I aim to map out the dynamic and complex assemblages of practices, actors, interests, markets and infrastructure that come into play and produce the local “possibility spaces” (Dittmer Citation2014) of future trajectories. I then argue that despite the multiple contingencies involved that make reliable predictions of future agrarian developments impossible, it is nevertheless possible to identify and sketch out probable tendencies based on the particularities of the dynamic context in which these changes take place.

In the following, I begin with a literature-based introduction to the CPEC-agriculture nexus, before presenting my conceptual approach and research methods. In the next section, I provide some contextual background on the study area in Gilgit-Baltistan, with a focus on recent developments in the farming sector. In the main part of the paper, I then conduct a critical analysis of the opportunities, risks and possible development trajectories of agricultural export for Gilgit-Gilgit-Baltistan through the CPEC, focusing on fruit production. The concluding section summarizes the most probable tendencies, addresses critical questions relating to market access and inclusive benefits and discusses the conceptual implications.

CPEC, agriculture and Gilgit-Baltistan

The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor can be regarded as the South Asian “flagship” project of China’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI): through a network of roads, railways and pipelines, western China will be connected to the newly constructed deep-water seaport of Gwadar in Pakistan’s Balochistan province – itself a central component of the CPEC (Lim Citation2019, 491). For China, the CPEC offers a new transport corridor to the Arabian Sea and thus an alternative to the long sea route via the Strait of Malacca (Lim Citation2019, 491). Moreover, through deepening the strategic partnership with Pakistan, an important motivation behind the CPEC appears to be the geostrategic positioning of China in South Asia vis-à-vis India (Garlick Citation2018). Apart from geopolitical goals in the context of the BRI, the CPEC is about intensifying economic relations between China and Pakistan; the former has clear economic interests in the latter as a major export market, and the Corridor offers business opportunities for Chinese companies in Pakistan’s construction, energy and other economic sectors (Wolf Citation2020; Syed and Ying Citation2020a). For Pakistan, in turn, the CPEC offers a major opportunity for much-needed investments in infrastructure and domestic industries, as well as access to new export markets. Promises are high, and the Pakistani government frames the CPEC as a “game changer” to boost economic growth (CPEC Secretariat Citation2017; International Crisis Group Citation2018).

The CPEC has been framed in terms of three different time scales: a short-term phase from 2015 to 2020, a mid-term plan until 2025 and a long-term plan until 2030 (CPEC Secretariat Citation2017). In the first phase, a number of “early harvest” projects were launched that primarily focused on the energy and transportation sectors, aiming to lay out the infrastructural foundations for economic cooperation and growth. According to Syed and Ying (Citation2020b, 3), “[b]y late 2018, seven early harvest projects (US$4.6 billion) had been completed and 12 projects (US$16.7 billion) were under construction,” with around 60% of the funds allocated to the energy sector, and the remainder mainly for transportation infrastructure (roads, railways and the Gwadar port). As of 17 March 2021, the official CPEC website (cpec.gov.pk) listed a total 14 projects as having been completed, with one of them implemented in Gilgit-Baltistan: a US$37 million project finished in 2018 (cpec.gov.pk, accessed 17 March 2021) to connect Rawalpindi with Khunjerab through fiber optic cable, thereby significantly improving local internet access along the CPEC route in Gilgit-Baltistan. In the second and third phases, in turn, the focus of the CPEC has been announced to shift toward other investments and projects, in order to foster economic development and bilateral cooperation. This includes the creation of Special Economic Zones throughout the country that offer tax exemptions and relaxed business regulations to foreign (not exclusively Chinese) investors across a wide range of industries, including textiles, pharmaceuticals, agro-based industries and food processing (Jahangir, Haroon, and Mirza Citation2020). One of these Special Economic Zones is foreseen for Gilgit-Baltistan: as stated on the official CPEC website (cpec.gov.pk, accessed 30 March 2021), among other industries related to marble and mineral processing, “fruit processing and value addition” enterprises will be encouraged to settle in a proposed area of 250 acres in Moqpondass, about 35 km from the regional capital Gilgit.

While a few details of other mid- or long-term projects have been revealed so far, the official CPEC long-term plan outlines the envisioned fields of Pakistan-China cooperation in various sectors and industries (CPEC Secretariat Citation2017). Before the publication of this 38-page document in late 2017, a 231-page draft, prepared by the China Development Bank and National Development Reform Commission of the People’s Republic of China, was “leaked” to the Pakistani newspaper Dawn (Husain Citation2017). Apparently, the draft described in great detail concrete projects involving economic cooperation, and “acquire[d] its greatest specificity, and [laid] out the largest number of projects and plans for their facilitation” (ibid.) in a sector that had played no role in the official CPEC narrative until that point, namely agriculture. These proposed projects and plans included, for instance, the introduction of drip irrigation technology from China to Pakistan, the establishment of demonstration plots by Chinese farm enterprises in Pakistan and the creation of fertilizer and food-processing plants through Chinese investments (ibid.). The draft also triggered some foreboding about possible “land grabbing” by Chinese agribusinesses (Khawar Citation2017; GRAIN Citation2021), albeit no such investments have become publicly known so far. The official long-term plan, however, dedicated only one page to outlining “agricultural development and poverty alleviation” as one of seven “key cooperation areas” (CPEC Secretariat Citation2017). Nevertheless, it can be expected that Pakistan’s agricultural sector will play a significant role in the second and third phases of the CPEC, as frequently stated by public officials (Suleri and Ramay Citation2020; The News Citation2021; Ahmed Citation2021). No tangible projects have been officially announced to date, but a new Joint Working Group on agriculture has been formed by the agricultural ministries of the two countries, which periodically meets to discuss priorities and prepare projects for agricultural cooperation and investment (Ahmad Citation2020; APP Citation2020; Chitral Times Citation2019). In total, ten Joint Working Groups have been formed under the CPEC umbrella (The Nation Citation2020), including one on socio-economic development that partly deals with agriculture. Formed by the Pakistan Ministry of Planning and the China International Development & Cooperation Agency, this working group is responsible for preparing and coordinating projects for the “Socio-economic Development under CPEC Framework”, for which the Chinese government recently pledged a grant of US$1 billion for “key areas of agriculture, education, health, poverty alleviation and vocational training” (Yousafzai Citation2020). Apparently, some early (probably rather small-scale) projects, including “agriculture technology laboratories” and the “provision of equipment & tools and demonstration stations in the agriculture sector,” have already been initiated (Planning Commission Citation2020), but no further information on these projects is available. It can be expected that a significant part of the US$1 billion grant will be used for agricultural projects, and the initiative promises to focus “on less developed parts of the country,” including Gilgit-Baltistan (Kiani Citation2019).

Since 2017, the nexus of the CPEC and agriculture has gained increased attention in academic and public policy debates in Pakistan. For instance, the Annual Report 2017–2018 of the State Bank of Pakistan dedicates a special section to agricultural opportunities for the nation through the CPEC, highlighting export opportunities to China and investment potential to address (infra-)structural constraints to agricultural growth and modernization (State Bank of Pakistan Citation2018). Moreover, CPEC plans have already been incorporated into the recently formulated National Food Security Policy of Pakistan. The policy outlines a plan to establish “CPEC Agricultural Development Zones” in all agro-ecological zones of the country to make use of opportunities to export “high-tech value- added agricultural products” to China (Government of Pakistan Citation2018b, 15):

The corridor crosses through the nine agro-ecologies [or defined agro-ecological zones of Pakistan]. On the basis of these agro-ecologies, the corridor is divided into 9 [sic] sections, each of which possesses distinct opportunities for establishing diverse agro-based businesses. Overall the establishment of agricultural economic zones along CPEC in collaboration with Chinese counterparts can help to achieve: a) food sovereignty; b) benefitting farmers and rural communities; c) smarter food production and yields; d) biodiversity conservation; e) sustainable soil health and cleaner water; f) ecological pest management; and g) resilient food systems.

In the various articles and policy reports that lay out and analyze the opportunities the CPEC offers to the agricultural sector, a common theme is that they highlight a significant export potential for agricultural produce to China (Ahmad Citation2017, Citation2020; CDPR Citation2018; Shafqat and Shahid Citation2018; Sher et al. Citation2019; Zulfiqar et al. Citation2019). Potential export crops are identified for various agro-ecological zones along the CPEC route(s), such as rice and mangoes in Sindh and Punjab, and temperate fruit crops in mountain areas (Ahmad Citation2020; CDPR Citation2018). For Gilgit-Baltistan, Shafqat and Shahid (Citation2018, 81) write:

In order to truly build export competitiveness policy makers will need to pay attention to building on the several local markets in which Pakistan has comparative advantage and negotiating more supportive tariff rates. For example, trade in goods that the Northern Pakistan [sic] has advantage in such as fresh and dry fruits in Gilgit-Baltistan do not show up as a major exporting good to China, despite the geographic proximity and the presence of the KKH [Karakoram Highway] to facilitate landbased trade.

Other authors share similar viewpoints, identifying great potentials of CPEC to boost the export of fruit or fruit products from Gilgit-Baltistan to China (Ahmad Citation2017; Zulfiqar et al. Citation2019; Khalique, Ramayah, and Farooq Citation2020). Indeed, in 2019, a delegation of Chinese fruit quarantine experts and government officials visited the area to lay the ground for importing fresh cherries from Gilgit-Baltistan via the CPEC route (Nation Citation2019).

The current policy and academic discourse on the CPEC and agriculture in Pakistan is predominantly optimistic, highlighting the potential to boost agricultural growth and open up new export markets. However, there are also concerns. As will be discussed more in detail below, unfavorable tariff rates and trade policies currently pose major barriers to exporting goods to China (Shafqat and Shahid Citation2018; Ahmad Citation2020). Moreover, as McCartney (Citation2020b, 13) has recently pointed out, several of the industrial- and agriculture-based products highlighted by the Pakistani government for export to China are “uncomfortably close” to what is produced in neighboring Xinjiang. This particularly applies to Pakistan’s prominent cotton and textile sector, as similar industries “are being promoted for domestic production and export from Xinjiang” (ibid.). McCartney also argues, albeit without providing specific examples, that fruits and vegetables suggested in CPEC literature for export to China seemingly compete with those promoted by China for domestic production in Xinjiang (ibid.). As I shall discuss, this may constitute a major risk for the fruit and nuts sector in Gilgit-Baltistan. More generally, current discussions on CPEC prospects suffer from a “near exclusive inward-looking focus on Pakistan” (McCartney Citation2020b, 1), and there is a need to better take into account development trajectories in western China.

Generally, the CPEC has received significant scholarly critique for its seemingly unrealistic and exaggerated promises to boost economic growth in Pakistan, its lack of transparency in planning and political decision-making, the risk of a “debt trap” (Lai, Lin, and Sidaway Citation2020) for Pakistan and the unequal distribution of its benefits in favor of China (see e.g. Lim Citation2019; McCartney Citation2020b; Wolf Citation2020). Furthermore, criticism has risen regarding the distribution of CPEC benefits within Pakistan, as infrastructural investments to date have favored the economic centers of the country, especially in the Punjab (International Crisis Group Citation2018; Karrar Citation2019; Kreutzmann Citation2020). The CPEC is framed by policymakers as a “highly inclusive” endeavor to provide “high-quality life” to the citizens of Pakistan (CPEC Secretariat Citation2017, 6). However, especially communities in the two “gateway” regions of the CPEC – Balochistan and Gilgit-Baltistan – fear that they merely serve as transit regions while being politically marginalized by the central government and deprived of the economic benefits of the CPEC (Wolf Citation2020; Kreutzmann Citation2020). Nonetheless, critical research on the exclusion of “in-between places” in Gilgit-Baltistan from CPEC benefits (Karrar Citation2019, 400; see also Rippa Citation2020b; Kreutzmann Citation2020) has paid little attention to the agricultural sector, where emerging opportunities and benefits may be distributed differently compared to infrastructure investments made to date.

CPEC, agriculture and assemblage trajectories

To make sense of the multiple dimensions, scales and mechanisms through which megaprojects operate, I take the CPEC as a complex assemblage involving infrastructure, geopolitical and economic interests, financial flows, contracts, agreements, discourses and numerous actors with different degrees of influence operating on various spatial and temporal scales. Assemblage thinking has been found to be a fruitful lens through which to investigate the complex social-spatial dynamics shaping the identities and everyday lives of borderland communities (Karrar and Mostowlansky Citation2018; Dean Citation2020) or the multi-scalar relationships and negotiation processes of BRI-related infrastructure projects (Alff Citation2020; Han and Webber Citation2020). Similarly, farming systems and agricultural markets can be conceptualized as complex social-material assemblages (Dwiartama, Rosin, and Campbell Citation2016; Dressler et al. Citation2018; Sharp Citation2018; Spies Citation2019), which can be regarded as a temporary arrangement of heterogeneous “parts” to form a sometimes stable, sometimes uneasy “whole” (DeLanda Citation2006). The components of an assemblage can be human and non-human, and they may be material (e.g. infrastructure, environmental constraints) and expressive (policies, discourses, etc.) (Spies and Alff Citation2020). Components are themselves assemblages and can be part of multiple assemblages at the same time, such as a road financed through the CPEC becoming an element of agricultural market assemblages by reducing transportation time. Moreover, there is no clear boundary between the CPEC and other forms of binational collaboration such as the China-Pakistan Free Trade Agreement, as they mutually affect each other and are partially driven by the same actors and interests. Hence, I regard the CPEC as an assemblage with very fuzzy boundaries that may reach far beyond its formalized scope of concrete investment projects, in both material and discursive terms (see also Lim Citation2019). Scrutinizing the CPEC through an assemblage lens also helps to avoid top-down or state-centric perspectives that are sometimes criticized as being dominant in BRI-related research (Hofman Citation2016; Jones and Zeng Citation2019): while some elements (e.g. Chinese and Pakistani state actors) are much more powerful than others, the outcomes of an assemblage are always co-produced by multiple other (human and non-human) actors through complex negotiation processes (Bennett Citation2005; DeLanda Citation2006).

The trajectories of an assemblage or its effects can never be fully predicted, as there are always contingencies involved. However, this does not mean that trajectories are entirely random, since assemblages always exhibit a certain degree of stability over time, and their trajectories are always context-dependent, i.e. they are restricted by other assemblages with which they have to engage (see e.g. Dittmer Citation2014). This makes it feasible to identify and evaluate possible – and probable – trajectories based on an inquiry of past and current developments, on the one hand, and on mapping out the complex social-material (and political-economic) assemblages that narrow down the possibility spaces, on the other. In the words of Dittmer, the aim is to “encounter tendencies” by “mapping the structure of a multidimensional ‘possibility space’” (Dittmer Citation2014, 392) – which can only be achieved on the basis of empirical observations.

To scrutinize on-the-ground practices and developments in Gilgit-Baltistan’s farming sector, and to relate them to the developments and policy debates around the CPEC and agriculture, I partially draw on long-term field research primarily focusing on the district of Nagar. During 11 months of field research in 2014–2016, I aimed at gaining a holistic understanding of the complex farming assemblages and their changes in recent decades in the context of various infrastructural, political, socioeconomic and environmental developments (Spies Citation2019). Data were primarily collected through qualitative interviews and numerous discussions with farmers and other local experts, and then triangulated with observations, transect walks and analyses of available gray literature. Most of the empirical data used for this paper were collected in 2019, when I re-visited the region during a two-month field trip to Pakistan that aimed at gaining a better understanding of the CPEC’s prospects for the agricultural sector of Gilgit-Baltistan and the province of Punjab (not addressed in this paper). The data from 2019 used for this paper were collected through expert interviews and discussions with around 25 key informants – mainly transboundary traders from Nagar, members of CPEC-related think-tanks, government officials and other key informants in Nagar, Sost, Gilgit (the capital of Gilgit-Baltistan), Islamabad and Rawalpindi. News articles, official trade data and policy documents served as important secondary sources of information.

Farming practices and dynamics of change in Gilgit-Baltistan

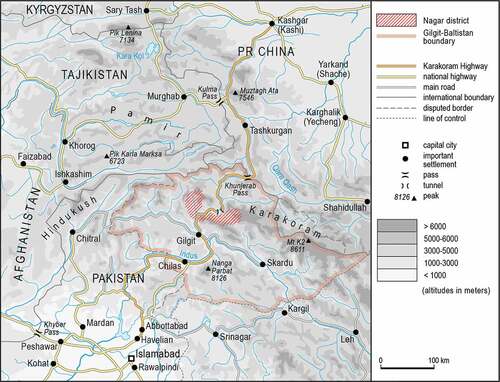

Bordering Afghanistan to the north, China to the northeast and India to the east, Gilgit-Baltistan covers some of the highest mountain terrains in the world (see ). The region has been administered by Pakistan for more than 70 years, but it is claimed by India as part of the wider Kashmir region (Kreutzmann Citation2015a). The status of Gilgit-Baltistan as a semi-autonomous region means that, among others, its approximately 1.3 million citizens (Government of Gilgit-Baltistan Citation2013) have no vote in national elections but only in electing the Gilgit-Baltistan Assembly, whose decision-making and legislation can be overruled by the prime minister of Pakistan (Kreutzmann Citation2020, 208; Government of Pakistan Citation2018a). While being disenfranchised of their national voting rights, the population enjoys a number of privileges compared to people in lowland Pakistan, such as tax exemptions and supplies of wheat, sugar and other basic consumption items at highly subsidized rates. Moreover, the region’s inhabitants can relatively easily obtain a “Pak-China Border Pass” that allows them to cross the border to Xinjiang multiple times a year for stays of up to one month (see Rippa Citation2020a, 62). The border pass has been extensively used for small-scale transboundary trade (Karrar Citation2019; Rippa Citation2019, Citation2020a), and some local traders managed to establish large and successful trade enterprises. Interestingly, transboundary trade via this routeFootnote1 is dominated by traders from the community and district of Nagar, on which this paper focuses, even though the district does not share a boundary with China (). The wealthiest men in Nagar have made their fortunes through transboundary trade since the 1990s, which enabled them to invest in various side businesses and to pursue political careers (Spies Citation2019). Moreover, many young men from Nagar work as porters at the dry port of Sost () on the Pakistani side of the border, where goods are inspected by customs officers and reloaded from Chinese to Pakistani trucks, or vice versa.

Figure 1. Gilgit-Baltistan and Nagar District (source: Kreutzmann Citation2015b, 13, reproduced and modified with permission from the original author).

Gilgit-Baltistan is a highly diverse region of currently 14 districts (Pamir Times Citation2019) that largely correspond to distinct socio-spatial entities based on shared historical, ethnolinguistic and denominational identities. For centuries, Nagar District was one of several autonomous princely states governed by a hereditary autocratic ruler. After the dissolution of the various microstates in today’s Gilgit-Baltistan in the early 1970s, and the opening of the Karakoram Highway in 1978, far-reaching societal changes occurred. Livelihoods used to be dominated by subsistence-oriented agriculture, but education, work migration to lowland Pakistan and other factors opened up new income opportunities in the off-farm sector. Today, Nagar has a population of approximately 60–70,000 people. While it is sometimes claimed that the economy of Gilgit-Baltistan is “largely based on agriculture” (Wolf Citation2020, 154; see also Ahmad Citation2017), at least in Nagar, farming has become a secondary source of income for most of the population. According to a survey in 2014–2015, only about one quarter of the average household income was derived from agriculture (Spies Citation2019, 150–52), with the main sources being off-farm work in the army, in education and the NGO sector, as well as various private enterprises, including trade. Since 2015, a boom in domestic tourism (Kreutzmann Citation2020) has generated new local income opportunities. A strong shift in livelihood priorities away from farming is also evident in other – if not all – parts of Gilgit-Baltistan (Kreutzmann Citation2006, Citation2020; Poerting Citation2017; Dittrich Citation1998; Pilardeaux Citation1997). In this regard, a decrease in farm sizes, due to population growth and partible inheritance, has played an important role as well; as a result, most farmers have very small landholdings, which barely allows for making a living solely based on agriculture. In Nagar, for instance, the median area of farmland per household is 0.25 ha, with only around 12% owning more than one hectare. In addition, land is unevenly distributed: approximately half of agricultural land is owned by around 15% of land owners, with some of the largest land holdings being in the hands of former ruling classes (Spies Citation2019, 151, 160). Nevertheless, the majority of households still own some agricultural land, and farming remains an important livelihood component for most households in Gilgit-Baltistan (AKRSP Citation2017).

Farming practices in this arid to semi-arid high-mountain environment combine irrigated crop production (mainly wheat, potatoes, maize and fodder crops) on village lands with animal husbandry (mainly cattle and small ruminants) that takes advantage of summer pastures at higher elevations. Moreover, fruit and nut production (mainly apricots, apples, cherries and walnuts) on irrigated orchards provides important additions to local diets. In correlation with infrastructural, socioeconomic and political developments, recent decades have seen major changes in the farming assemblages of Nagar (cf. Spies Citation2019). On the one hand, a certain degree of modernization is evident through the introduction of chemical fertilizers and agricultural machinery, among others. On the other, because of changing livelihood priorities households tend to simplify cultivation techniques and have given up particularly time-consuming practices such as herding livestock and cultivating remote fields in summer settlements.

At the same time, there has been a considerable shift from subsistence farming to commercial crop production. The staple crop wheat has been replaced by potatoes as the dominant field crop, produced since around the early 2000s as a cash crop for lowland Pakistan. Moreover, farmers increasingly plant fruit trees on agricultural land for commercial production, mainly apricots, apples, walnuts and cherries, usually sold fresh (apples, cherries) and dried (apricots, walnuts) through local or regional agents to markets in lowland Pakistan. A small share of the dried fruits is occasionally exported to Europe, North America, Japan and, until recently, China (see below). Among others, due to improved transport infrastructure for this highly perishable fruit, cherries have become the most profitable cash crop for domestic markets in recent years. Cherry trees have thus increasingly gained popularity among farmers, not only for their high income potential, but also because they require less labor than arable crops, as most farmers sell their production for a lump sum to local traders who take care of the harvest themselves (Spies Citation2019). Local cherry traders report that cherry production in Nagar has more than doubled over the past 10 years, and the trend continues, with many new cherry trees being planted every year. These ongoing dynamics and local specifics of farming systems need to be taken into account when evaluating the possibility spaces of CPEC-related developments.

Export prospects and trajectories for local farming communities

As previously mentioned, academic and policy discussions on the CPEC and agriculture in Gilgit-Baltistan emphasize the need to unlock export potentials to China, in particular for fruits. In this sense, the CPEC is regarded as a larger policy assemblage that covers much more than investment projects, namely bilateral negotiations, trade deals and an overall intensification of economic exchange and collaboration between Chinese and Pakistani state and non-state actors. This assemblage needs to be leveraged in order to get the best out of it for local farmers, not only through concrete CPEC-financed measures such as improving logistical trade infrastructure, but also by creating an enabling policy framework, attracting Chinese (trade) companies and establishing reliable partnerships (see e.g. Ahmad and Khan Citation2018; Ahmad Citation2020; CDPR Citation2018). Thus, while little can be said about concrete investment projects in the agricultural sector of Gilgit-Baltistan to date, it does make sense to take a closer look at actual developments related to agricultural exports and to conduct a more locally grounded, critical investigation of the opportunities, risks and probable tendencies involved. As such, I now focus on the fruit production sector as the seemingly most promising area for export-oriented agriculture, before discussing other potential farm-related export commodities.

Cherries for China?

In summer 2019, a delegation of Chinese fruit quarantine experts and government officials visited Gilgit-Baltistan to investigate opportunities to import fresh cherries into China. They visited cherry orchards, checked for fruit quality and pests and diseases and took samples for laboratory analysis. The event was well-covered in the media, and the outcome was promising: the delegation was satisfied with fruit quality, packaging and the absence of pests, and it promised to officially recommend imports to China (Kamani Citation2019; The Nation Citation2019). When I discussed the matter a few months later with traders from Nagar, some were very optimistic that cherry export would be beginning in summer 2020. One well-connected trader and local politician enthusiastically predicted an export volume of 50 containers (or 1500 tons) of cherries from Gilgit, Hunza and Nagar Districts, which would be a major share of the total production estimated at 4,000 tons annually for Gilgit-Baltistan (Ebrahim Citation2016; The Nation Citation2019).Footnote2 Apparently, some “high level officials” and committed Chinese businessmen were present, which made some of the traders confident that cherry export would be realized soon (field note, Sost, Nov. 2019). The traders had been promoting cherry export for several years,Footnote3 and now it seemed their efforts were coming to fruition.

Given the huge amounts of cherries that China imports primarily from Chile and the US every year, a strong demand for this fruit is evident (DCCC Citation2020). To facilitate cherry export via the Khunjerab Pass, an effective fruit quarantine system would be set up at the dry port of Sost, to ensure the required sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) standards, fruit quality and packaging. As my informants explained, the main concern voiced by the experts from China was fruit flies, but cherries in this mountain region have so far been free of this pest (see also Kamani Citation2019; The Nation Citation2019).

Considering the strict border closures and severe trade interruptions during the Covid-19 pandemic, it is perhaps not surprising that no cherries were exported to China in 2020. However, in 2019, the majority of traders and other informants I talked to were already highly skeptical about trade prospects. As one interlocutor put it during a discussion at the Sost dry port, “They [Chinese officials/businessmen] make commitments in winter, but nothing happens in summer” (field note, Sost, Nov. 2019). Located at 4,600 m asl, the border at Khunjerab Pass () is closed during the winter months. What made the traders particularly skeptical is that exporting agricultural produce to China has become very difficult in recent years. In particular, for many years, they exported Pakistani dry fruits and nuts – mainly apricots and walnuts – via the Karakoram Highway, but recently they had to give up this business, due to severe restrictions enforced by Chinese authorities.

Barriers to fruit export

Transboundary trade with dry fruits from Pakistan has existed since at least the 1980s, when haj pilgrims from Xinjiang traveled to Mecca via Pakistan and the Karakoram Highway and carried Pakistani goods with them on their return journey (Kreutzmann Citation2020, 192). Most of the interviewed traders from Nagar started their business in the 1990s. Dry fruits (mainly apricots) and nuts (mainly walnuts) were among the few goods they exported to China, while the main profit was usually made by importing Chinese items into Pakistan (field notes, Sost, Nov. 2019). Trade has always been a one-sided affair: over the last decade, the total annual value of goods exported to China via the Khunjerab Pass has been about 0.7–7% of the goods crossing the border into Pakistan (Khan Citation2019; Kreutzmann Citation2020, 209). Moreover, as the traders explain, in recent years it has become virtually impossible to export food items, due to increasingly restrictive import policies instigated by China. Rippa, for instance, describes the case of a trader from Nagar who had to give up on his dry fruit export business to China due to a heavy tariff increase in 2016, just before they were lowered again (Rippa Citation2019, 11–12). More generally, trade in both directions has become much more difficult, due to increasingly complex customs regulations, unpredictable and seemingly prohibitive tariff policies as well as tight security measures enforced by Chinese authorities – all of which has made transport and personal exchange between traders more difficult (Rippa Citation2019, Citation2020a; Karrar Citation2019).

It appears that more recently, increasingly prohibitive SPS requirements rather than tariff policies have become the main export barrier. According to the traders I talked to in 2019, the last shipment of dry fruits they successfully exported was in 2016. Furthermore, the business has become too risky: once the shipment reaches Tashkurgan Dry Port, it is subject to lengthy and increasingly strict quarantine protocols, and it can be sent back if it fails to meet a set of strict requirements. This happened to one interviewed trader who made a last attempt in 2018: after sending several containers of dry fruits (apricots and cherries) across the Khunjerab Pass, the shipment did not pass inspections at Tashkurgan Dry Port, and it took several months until the decision was made that all fruits must be returned to Pakistan. As a result, he made a “huge loss”, due to large expenses for storing the goods in Tashkurgan during that period (field note, Sost, Nov. 2019). Based on such experiences, the traders are highly skeptical that exporting fresh cherries would be worth the risk, given that the fruits spoil quickly and that a very effective and reliable system of SPS measures, packaging and cold chain management needs to be set up. According to a government officer from Gilgit, plans to establish a special facility for this purpose at Sost Dry Port have existed for many years, but they have not been realized so far. As an interviewed senior member of a CPEC think-tank emphasized, the lack of effective systems and protocols in Pakistan to meet the SPS requirements of China is seemingly the main barrier for exporting fresh fruits – not only cherries from Gilgit-Baltistan, but also mangoes from the Punjab that have a considerable demand in China as well. In his opinion, it is ironic that in the second phase of the China-Pakistan Free Trade Agreement that became effective in January 2020, import tariffs by China were eliminated for dozens of agricultural products from Pakistan that can de facto not be imported due to strict SPS requirements (field note, Islamabad, Dec. 2019). In the amended free trade agreement, a total of 313 food items were added to the list of duty-free imports to China, including fresh cherries and 63 other items categorized as processed or unprocessed food (Government of the People’s Republic of China and Government of Pakistan Citation2019).

Given that transboundary trade with dry fruits was possible for decades, traders from Nagar perceive the increasing export barriers as part of a presumed protectionist agenda by China to promote its own production. This assumption can be supported by the fact that neighboring Xinjiang has seen a stark trend of policy-driven agricultural diversification toward fruit and nut production over the last 10–15 years. As Spoor, Shi, and Chunling (Citation2015) describe, since the mid-2000s, agricultural policies in Xinjiang have heavily focused on planting fruit and nut trees – mainly apricots, jujube, almonds and walnuts. Provided with “massive technical assistance, seeds and credit facilities”, farmers have been “strongly ‘advised’ to practice intercropping of cotton or wheat with fruit and/or nut trees” (Spoor, Shi, and Chunling Citation2015, 145). Moreover, significant investments have been made in marketing and processing facilities and fruit tree research and development. As a result, the planting area for fruit trees in Xinjiang officially increased from about 667,000 ha to around 1.13 million ha between 2000 and 2010 (ibid.). For instance, in Aksu, the main cotton-producing prefecture of Xinjiang, the area allocated to apricot trees increased from 13,300 ha in 2001 to around 33,800 ha in 2009, and production output increased more than fivefold. Similar trends also occurred “in the production of other fruits, as well as in the more traditional almond and walnut crops” (ibid., 146).

Thus, there appears to be competition with at least two crops that are widely produced in Nagar and other parts of Gilgit-Baltistan and which used to be exported to China, namely apricots and walnuts. Discussions with traders and shopkeepers in Nagar revealed a noteworthy development in this regard. Until a few years ago, walnuts from Gilgit-Baltistan were exported to China via the Khunjerab Pass, albeit on a rather small scale, but due to reduced demand (and probably export barriers), it is no longer profitable to do so. According to official trade data reported by China, the last shipments of walnuts (in shell, fresh or dried) were imported from Pakistan in 2014 (ITC Trade Map Citationn d). Since 2016, the opposite has occurred, in that China has exported walnuts to Pakistan at steadily increasing volumes, reaching 10,600 tons or a total trade value of US$41 million in 2019. In contrast, annual walnut imports from Pakistan into China reached an exceptional maximum of 696 tons worth US$1.4 million in 2013, followed by a sharp decline to 218 tons with a trade value of only US$ 202 million (ibid.) in 2014.Footnote4 China is the leading walnut producer worldwide, and Xinjiang has recently replaced Yunnan as the main walnut-producing region of the country (Produce Report Citation2019). As a shopkeeper in Nagar showed me, the imported walnut varieties are larger than the local ones, and their smooth and bright shells are much easier to crack open, thereby making the imported walnuts more popular among consumers compared to local walnuts, despite their higher prices and, as my informants from Nagar assure me, inferior taste and nutritional value. This development was reason for concern among my interview partners in Nagar, who feared that local production could not compete with the imported walnuts and that farmers would see a significant drop in prices. Moreover, this development was often perceived as a general pattern of agricultural trade with China, as a trader in Sost explained when asked about his thoughts on prospective cherry export:

If cherries start to get exported, it might be similar as with walnuts: first, export from Pakistan, then they make allegations in China and stop the trade. After two years, they will produce the fruits themselves and export them to Pakistan! (field note, Sost, Nov. 2019)

Indeed, domestic cherry production in China is increasing steadily, with Xinjiang being among the more recently emerged growing regions (Courtney Citation2020; GAIN Citation2020). Thus, there is a need to be cautious. Cherry export could indeed be very profitable for farmers in Gilgit-Baltistan, since, according to cherry traders in Nagar, farmers get paid around PKR 50–70 per 700 g box of cherries (field note, Minapin, Nov. 2019), while reported farm gate prices in China during the harvest season in May/June are approximately 5–10 times higher (around US$2.90–5.80 or ¥20–40 per kg; GAIN Citation2020). In the long term, however, this may change with the expansion of large-scale cherry orchards in China and with emerging imports from Central Asian countries (GAIN Citation2020). Nonetheless, given the high cherry demand in China and the recent abolishment of import duties, at least in the upcoming years, if not decade, exporting cherries to China should be economically worthwhile.

Limited prospects for local farmers

While cherries could indeed be a very profitable export commodity in the coming years, I have already pointed out that export barriers are currently very high. Moreover, there are also rather local constraints that have not been mentioned so far. In addition to lacking fruit inspection and quarantine facilities at the dry port of Sost, current production, packaging and transportation systems will unlikely satisfy China’s SPS requirements. As existing deals with other cherry-exporting countries indicate, requirements may include specialized packaging facilities and certain production standards (e.g. single-crop orchards) with regular orchard inspections and full traceability of producer origin, among others.Footnote5 Most likely, it will be primarily larger-scale cherry farmers who benefit from this export opportunity, while the vast majority of farmers may not be able to access Chinese markets at all: with median landholdings of only 0.25 ha per household, individual production is likely too small to make the licensing procedure worthwhile – if small farmers are able to fulfill the required production standards at all. Here, we can draw on recent insights from the emerging cherry export market from Central Asia to China since 2015, where small land holdings and a lack of “financial and knowledge resources” of the majority of farmers have been identified as principal barriers for entering the Chinese marketplace (World Bank Citation2020, 10). In Kyrgyzstan, for instance, deals are concluded directly between local producers and Chinese importers (usually small- to medium-sized enterprises). As described in a recent World Bank report, “[o]nly cherries produced in the orchards that passed the inspection by the Chinese counterparts [were] allowed for export”, and by 2018, a total of 14 cherry producers exported 68.7 tons of cherries worth US$217,800 to China (ibid., 32–33). Based on a cherry yield estimated at 5 t/ha for Kyrgyzstan (ibid., 35), this would mean that farmers with an average of one hectare of cherry orchard were able to export their produce. While one hectare may not seem particularly large, in Gilgit-Baltistan the vast majority of farmers would not be able to produce cherries on such a scale, because not only are cherry orchards – and total landholdings of most households – significantly smaller, but they are also often fragmented into several pieces of land located in different places. Thus, at least for this commodity, there is reason for skepticism about the promised “highly inclusive” character of the CPEC (CPEC Secretariat Citation2017, 7) when it comes to export opportunities in the agricultural sector. Much will depend on the SPS agreements made between China and Pakistan: if the defined production and licensing standards allow for the small-scale, decentralized cherry production prevalent in the region, farmers may be able to cooperatively sell their produce to Chinese buyers. In recent years, similar arrangements have been made between apple farmers and major supermarkets in lowland Pakistan through “Local Support Organizations”, i.e. registered NGOs that usually act as brokers or partner organizations for external donors and government agencies (Spies Citation2019). However, considering that agricultural policies in Pakistan are often narrowly technocratic and productivity-oriented, thus neglecting the specific needs of small farmers (Alff and Spies Citation2020), it remains to be seen whether such arrangements will be a priority in bilateral negotiations with their Chinese counterparts.

Moreover, there are other risks as well. As previously mentioned, market demand in China might decrease in the long term, and the emergence of new pests could suddenly stop export arrangements completely. While cherries in the region are currently pest-free, there is always a risk of cherry fruit flies emerging in Gilgit-Baltistan, as a senior government employee related to pest management in Gilgit explained (field note, Nagar, Nov. 2019), so naturally, relying on a single crop when investing in export-oriented production would not be wise. Given recent trade barriers and agricultural developments in Xinjiang, dried apricots and walnuts are seemingly not an option, but what other possibilities exist for Gilgit-Baltistan?

Other export potentials?

While food exports to China via the Khunjerab Pass have largely come to a halt in recent years, there is one exception: pine nuts. Due to an export boom of the product to China, domestic prices have recently surged (see Saeed Citation2019). Some of the traders I interviewed were themselves involved in export and argued that it is currently a very profitable business due to the high demand in China. Most of the exported pine nuts, however, are collected in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa or smuggled into Pakistan from Afghanistan, while pine forests only exist in small parts of Gilgit-Baltistan.

Other important crops currently produced in Gilgit-Baltistan for domestic markets are potatoes and apples, but there is already a major production surplus in China for both crops that are exported to other countries on a large scale (ITC Trade Map, n.d.). Ahmad (Citation2017, Citation2020) identifies trout farming as a priority to be promoted in Gilgit-Baltistan through the CPEC, in order to cater to both domestic and export markets. Producing trout for export to China could indeed be a profitable business, and the Government of Pakistan seems willing to leverage the CPEC for expanding this industry. For instance, in collaboration with a Chinese research institution, the Pakistan Agricultural Research Council (PARC) recently established a trout research station and farm near Gilgit to promote the expansion in the region (Irfan Citation2019). As a local informant involved in trout farming told me, there are future plans to export trout across the border to China, and “technical issues related to food licensing” have already been discussed (phone conversation, Feb. 2021). China is already a major importer of Pakistani seafood transported by ship or air, and export volumes from Pakistan are increasing steadily (ITC Trade Map Citationn d). Trout, in turn, are currently imported into China mainly in frozen form from Norway, Chile and a few other countries, none of which borders China (ibid.). Trout could therefore be a suitable niche market in China for producers from Gilgit-Baltistan, where production may be branded as more healthy and “natural” compared to the highly industrialized aquacultures of major trout-producing countries. However, exporting trout from the region would require setting up an entirely new food safety and sanitation scheme and a reliable cold chain transportation system, which makes this endeavor relatively unlikely on a significant scale anytime soon. In any case, trout farming will remain an economic niche for a small number of local entrepreneurs, much more so than cherry production: it is limited to a few locations with abundant and reliable all-year freshwater supply, and it requires significant investment in setting up the required infrastructure, among other issues.

Ahmad (Citation2017, Citation2020) notes that agriculture in Gilgit-Baltistan could potentially address another niche market, namely organic food. Fruits, in particular, are mainly produced without the use of pesticides and with little or no chemical fertilizer, which means that organic standards can be easily achieved. There is indeed a relatively small but nonetheless growing market for organic food in China, with middle- and upper-class consumers increasingly demanding healthy, often imported products, while mistrusting food safety standards of conventional domestic production (Hasimu, Marchesini, and Canavari Citation2017; Wu et al. Citation2014). However, in order to access such markets with fruits (fresh or dried) and nuts from Gilgit-Baltistan, barriers related to SPS requirements will probably be similar to – if not higher than – those mentioned above, in addition to the expenses involved in organic certification. Especially for small farmers, these barriers are probably higher than those to exporting “conventional” fruits.

This may be different in the long term, if proposed CPEC investments in Gilgit-Baltistan are realized. As previously mentioned, one aim of the planned Special Economic Zone (SEZ) in Moqpondass near Gilgit is to establish a fruit-processing industry by attracting foreign (especially Chinese) and domestic investors to set up their businesses in the zone. According to a businessman currently establishing a Chinese-Pakistani joint venture in an already existing SEZ in Pakistan, not only the promised tax holiday of 10 years and other economic benefits, but also a much smoother and less arduous bureaucratic procedure than usually found in Pakistan will be attractive features of these CPEC-financed SEZs (field note, Lahore, Dec. 2019). Thus, if Chinese fruit-processing companies settle in Moqpondass to produce packaged (organic or conventional) fruit juices or jams for Chinese markets, barriers to selling fruits may be lower for local farmers compared to export schemes for fresh fruit. Moreover, as a Nagar trader somewhat polemically explained, trade barriers are generally lower for Chinese than for Pakistani entrepreneurs:

If some Chinese investor wants to [import agricultural products to China], they [Chinese customs officers] allow him to import; they do not even check the containers. If Nagarkuts [people from Nagar] or Pakistani want to trade, they make hurdles! Even if they [Chinese businesspersons] wanted to import cow manure to China, they could do it! (field note, Sost, Nov. 2019).

However, it remains to be seen whether the SEZ or other CPEC-related means will really create a new food-processing and value addition industry at a reasonable scale from which the farmers will benefit. The food-processing sector in Pakistan is already dominated by Western multinational corporations, in particular PepsiCo and Nestlé, with the latter being the leading brand for fruit juices, with several production facilities operating in the country (see the official website www.nestle.pk). According to my informants, Nestlé is currently becoming increasingly active in the region: in 2019, for instance, the company purchased 40 tons of apples through a Local Support Organization in Nagar, and it was planning to expand its purchasing activities in subsequent seasons (field note, Nagar, Nov. 2019). Thus, it may not be considered economically worthwhile for Chinese companies to enter this sector – but maybe other international and domestic investors could take advantage of the SEZ to expand their fruit-processing business to Gilgit-Baltistan. At this point, however, it is too speculative to outline tendencies in this regard. There are many open questions, among others regarding contractual arrangements, prices offered to farmers as well as the energy and water needs of a food-processing factory in this area where both resources are scarce.

In sum, there are indeed potential opportunities for farmers from Gilgit-Baltistan to benefit from emerging export opportunities facilitated through the CPEC, but one should not expect miracles. Considering recently increased trade barriers and the resulting export decline of local products, such arrangements are unlikely to emerge on a significant scale anytime soon. Moreover, local benefits are unlikely to be inclusive: only larger-scale farmers may be able to meet the required production standards, while the vast majority of small farmers may not be able to access Chinese markets at all.

Conclusion

This paper has revealed two main contradictions between promises made in relation to the CPEC for agricultural export in Gilgit-Baltistan and empirical tendencies observed on the ground. First, recent developments oppose rather than support the CPEC narrative of boosting the export of agricultural produce, particularly mountain fruits. Overall, with the exception of pine nuts, food exports to China via the Khunjerab Pass have largely come to a halt, the main reasons for which include increasing SPS restrictions enforced by Chinese authorities, as well as growing competition in terms of fruit and nut production with Xinjiang. Second, the CPEC’s long-term plan promises inclusive development and benefits for all citizens, but local farming structures, the nature of export barriers and experiences of Chinese fruit imports from other countries indicate that seemingly, only a minority of better-off farmers with larger landholdings will be able to sell products to Chinese markets. This is particularly the case for fresh cherries, the most promising agricultural commodity from Gilgit-Baltistan for export via the Khunjerab Pass.

Recent developments suggest that cherry export to China is not likely to take off in the upcoming years. Apart from cherries, however, there is little potential in other local (agricultural) crops, due to competition with producers in Xinjiang and other parts of China. Trout farming, catering to niche markets in China, could be an option for a number of local entrepreneurs with suitable land resources and sufficient financial means, but technical barriers are high. Producing organic fruits and nuts for emerging organic food markets in China may have potential as well, but again, the vast majority of small farmers may not be able to fulfill – or afford – the required SPS measures and organic certification standards. This may be different when CPEC plans are implemented to establish the proposed food-processing industry in the planned SEZ at Moqpondass. So far, however, this proposal exists only on paper. As an interviewed businessman stated regarding the announced SEZs, “What is written on the websites is just written there; it does not mean much. This is Pakistan” (field note, Lahore, Dec. 2019).

Nevertheless, if infrastructural and resource conditions allow, establishing a fruit-processing industry in Moqpondass (or any other place in the region) could provide benefits for small farmers by offering a new market for their agricultural produce and potentially driving selling prices. However, the Government of Gilgit-Baltistan, the future managing authority of the Special Economic Zone, will need to consider carefully the types and aims of companies seeking to settle there, their proposed forms of collaboration with local farmers and the sustainability of their local resource needs, among others. My informants argued that the Special Economic Zones will be open to all foreign and domestic investors (see also Haider Citation2020), but given the lack of transparency in CPEC negotiations and agreements, it remains to be seen to what extent Chinese investors will be given preference. However, what matters most to local farmers are reasonable prices as well as reliable and uncomplicated selling arrangements for their relatively small quantities of produce. Likewise, to ensure that not only local elite farmers have a chance to benefit from emerging export opportunities for cherries, trade arrangements and SPS measures need to allow for cooperative marketing schemes or involve local middlemen to enable small-scale producers to access markets in China. At least in Nagar District, mutually beneficial arrangements between small farmers and local cherry traders from the same community are already in place, and producers often do not have the time or resources available that direct marketing would require. Trade deals that allow for such arrangements for cherry export may be very difficult to achieve, but they would be a precondition for making this endeavor an inclusive one.

This study has demonstrated that making reasonable judgments on CPEC prospects for local farmers requires a sound understanding of both local realities and translocal developments shaped by a diverse range of actors and interests on various scales. Market developments in China, along with bi-national deals, will play important roles – but so will structural conditions, local negotiation processes between farmers, traders, enterprises and various other actors, as well as infrastructural developments and investments related to transport logistics and food inspection and quarantine, among others. To bring together and make sense of these heterogeneous factors and actors, who are commonly analyzed in isolation from each other, I followed an assemblage-inspired approach combining empirical insights and a variety of secondary data. On the one hand, conceiving local developments as assemblage trajectories offers a fruitful way of identifying probable tendencies based on particular empirical realities while acknowledging the multiple contingencies involved. On the other hand, this approach offers a flexible way to make use of diverse research methods and data and to avoid getting trapped in disciplinary boundaries. This is particularly useful for scrutinizing complex subject matter such as the CPEC-agriculture nexus, which cannot be understood by narrowly looking at production potentials while neglecting both local farming contexts in Pakistan and dynamics in China – as currently the case in much of the literature.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The largest share of goods traded between Pakistan and China is currently transported via sea, and only an estimated 1–4% travels via the CPEC route (Shafqat and Shahid Citation2018; Rippa Citation2019). The significantly lower costs of sea transport and the infrastructural constraints of transporting goods along the Karakoram Highway make it unlikely that this share will significantly increase in the future (McCartney Citation2020a).

2. Based on interviews with local cherry traders, I would estimate the total production in Nagar District in 2019 at around 600–1200 tons.

3. Discussions about the export potential of fresh cherries to China seemingly predate the CPEC: Around 2014 or 2015, the chairman of Sinotrans Xinjiang, a Chinese state-owned enterprise managing the dry port at Sost until 2016, proposed in a speech in Hunza to export local cherries to China (Karrar Citation2021).

4. Pakistan, however, reports very different numbers: only 66 tons of exported walnuts (fresh or dried, in shell) worth 136,000 US$, and imports of 3,000 tons with a trade value of 6,300,000 US$ in 2019 (UN Comtrade Database, n.d.). While the reasons for this stark discrepancy remain unclear, the overall trends are similar. Generally, it appears that the bilateral trade data reported by China are more comprehensive.

5. See, for instance, the phytosanitary agreements for cherry import to China between China and Turkey (https://www.tarimorman.gov.tr/GKGM/Belgeler/DB_Bitki_Sinir/Son_Kiraz_Protokolu_EN.pdf) and China and Australia (https://micor.agriculture.gov.au/Plants/Protocols%20%20Workplans/China%20-%20Cherries%20Protocol.pdf)

References

- Ahmad, Mahmood. 2017. “China Pakistan Economic Corridor: Trade and Agriculture.” In The State of the Economy. China Pakistan Economic Corridor. Review and Analysis, edited by BIPP, 86101. BIPP 10th Annual Report 2017. Lahore: Shahid Jeved Burki Institute of Public Policy at NetSol.

- Ahmad, Mahmood. 2020. “Developing a Competitive Agriculture and Agro-Based Industry under CPEC.” In China’s Belt and Road Initiative in a Global Context: Volume II: The China Pakistan Economic Corridor and Its Implications for Business, edited by Jawad Syed and Yung-Hsiang Ying, 227–270. Springer International Publishing. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan Asian Business Series. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-18959-4.

- Ahmad, Mahmood, and Mahira Khan. 2018. “Agriculture and Trade Policies under CPEC with Focus on China.” In The State of the Economy. Pakistan’s New Political Paradigm – an Opportunity to Make the Most of CPEC, edited by BIPP, 58–69. BIPP 11th Annual Report 2018. Lahore: Shahid Jeved Burki Institute of Public Policy at NetSol.

- Ahmed, Amin. 2021. “Call for Exploiting Agriculture Potential under CPEC.” Dawn, January 7.

- AKRSP. 2017. “Horizons of CPEC in Gilgit-Baltistan: A Prospective Study.” Technical report. Gilgit: Aga Khan Rural Support Programme (AKRSP), retrieved 21 January 2021. http://akrsp.org.pk/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Horizons-of-CPEC-in-Gilgit-Baltistan.pdf.

- Alff, Henryk. 2020. “Belts and Roads Every- and Nowhere: Conceptualizing Infrastructural Corridorization in the Indian Ocean.” Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space. Special Issue on “Politics and Spaces of China’s Belt and Road Initiative,” 21–25. doi:10.1177/2399654420911410.

- Alff, Henryk, and Michael Spies. 2020. “Pfadabhängigkeiten in der Bioökonomie überwinden? Landwirtschaftliche Intensivierungsprozesse aus sozial-ökologischer Perspektive.” PERIPHERIE 159/160 (40): 334–359. doi:10.3224/peripherie.v40i3-4.06.

- APP. 2020. ”Pak-China Joint Working Group Holds Second Meeting on Agriculture.” Associated Press of Pakistan (APP), April 27.

- Bennett, Jane. 2005. “The Agency of Assemblages and the North American Blackout.” Public Culture 17 (3): 445. doi:10.1215/08992363-17-3-445.

- CDPR. 2018. “Agriculture Sector Opportunities in the Context of China-Pakistan Economic Corridor.” In Agriculture Sector Opportunities in the Context of China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. Lahore: Consortium for Development Policy Research (CDPR) & International Growth Center (IGC).

- Chitral Times. 2019. “China–Pakistan Joint Working Group (JWG) Meeting between the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of China and Held.” Chitral Times, November 1.

- Courtney, Ross. 2020. “Chinese Cherries: A Growing Industry.” Good Fruit Grower, accessed 26 January 2021. https://www.goodfruit.com/chinese-cherries-a-growing-industry/.

- CPEC Secretariat. 2017. “Long Term Plan for China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (2017-2030).” Retrieved 6 November 2020. http://cpec.gov.pk/brain/public/uploads/documents/CPEC-LTP.pdf .

- DCCC. 2020. “Cherry Chinese Importers are Looking for Seasonal Suppliers.” Direct China Chamber of Commerce (DCCC), accessed October 7, 2020. https://www.dccchina.org/news/cherry-chinese-importers-are-looking-for-seasonal-suppliers/ .

- Dean, Karin. 2020. “Assembling the Sino-Myanmar Borderworld.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 61 (1): 34–54. doi:10.1080/15387216.2020.1725587.

- DeLanda, Manuel. 2006. A New Philosophy of Society: Assemblage Theory and Social Complexity. London and New York: Continuum.

- Dittmer, Jason. 2014. “Geopolitical Assemblages and Complexity.” Progress in Human Geography 38 (3): 385–401. doi:10.1177/0309132513501405.

- Dittrich, Christoph. 1998. “High-Mountain Food Systems in Transition: Food Security, Social Vulnerability and Development in Northern Pakistan.” In Transformation of Social and Economic Relationships in Northern Pakistan, edited by Irmtraud Stellrecht and H.-G Bohle, 231–254. Köln: Köppe.

- Dressler, Wolfram H., Will Smith, J.F. Marvin, and Montefrio. 2018. “Ungovernable? the Vital Natures of Swidden Assemblages in an Upland Frontier.” Journal of Rural Studies 61: 343–354. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.12.007.

- Dwiartama, Angga, Christopher Rosin, and Hugh Campbell. 2016. “Understanding Agri-Food Systems as Assemblages: Worlds of Rice in Indonesia.” In Biological Economies: Experimentation and the Politics of Agri-Food Frontiers, edited by Le Heron Richard, Hugh Campbell, Nick Lewis, and Michael Carolan, 82–94. London and New York: Routledge.

- Ebrahim, Fofeen T. 2016. “The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor Winds through Gilgit-Baltistan.” Thethirdpole.Net,accessed 25 January 2021 . https://www.thethirdpole.net/2016/01/28/the-China-Pakistan-economic-corridor-winds-through-gilgit-baltistan/.

- GAIN. 2020. “Stone Fruit Annual - People’s Republic of China.” Annual Report CH2020-0095. Global Agricultural Information Network (GAIN), accessed 1 March 2021. https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/Report/DownloadReportByFileName?fileName=Stone%20Fruit%20Annual_Beijing_China%20-%20Peoples%20Republic%20of_07-01-2020.

- Garlick, Jeremy. 2018. “Deconstructing the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor: Pipe Dreams versus Geopolitical Realities.” Journal of Contemporary China 27 (112): 519–533. doi:10.1080/10670564.2018.1433483.

- Government of Gilgit-Baltistan. 2013. “Gilgit-Baltistan at a Glance 2013.” Statistical report by Statistical Cell, Planning and Development Department, Government of Gilgit-Baltistan. Gilgit. retrieved 15 March 2015. http://www.gilgitbaltistan.gov.pk/DownloadFiles/GBFinancilCurve.pdf.

- Government of Pakistan. 2018a. An Order to Provide for Political Empowerment and Good Governance in Gilgit-Baltistan. Islamabad: Government of Pakistan, Ministry of Kashmir Affairs and Gilgit Baltistan.

- Government of Pakistan. 2018b. National Food Security Policy. Islamabad: Government of Pakistan, Ministry of National Food Security and Research.

- Government of the People’s Republic of China and Government of Pakistan. 2019. Protocol to Amend the Free Trade Agreement between the Government of the People’s Republic of China and the Government of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. Accessed 19 March 2021. https://www.commerce.gov.pk/protocol-on-phase-ii-China-Pakistan-fta/.

- GRAIN. 2021. “Unmasking the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor.” GRAIN, accessed 16 July 2021. https://grain.org/en/article/6669-unmasking-the-China-Pakistan-economic-corridor#sdfootnote7sym .

- Haider, Mehtab. 2020. “China Has No Objection to Foreign Investment in SEZs under CPEC: Envoy.” The News, March 11.

- Han, Xiao, and Michael Webber. 2020. “From Chinese Dam Building in Africa to the Belt and Road Initiative: Assembling Infrastructure Projects and Their Linkages.” Political Geography 77: 102102. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2019.102102.

- Hasimu, Huliyeti, Sergio Marchesini, and Maurizio Canavari. 2017. “A Concept Mapping Study on Organic Food Consumers in Shanghai, China.” Appetite 108: 191–202. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2016.09.019.

- Hofman, Irna. 2016. “Politics or Profits along the ‘Silk Road’: What Drives Chinese Farms in Tajikistan and Helps Them Thrive?” Eurasian Geography and Economics 57 (3): 457–481. doi:10.1080/15387216.2016.1238313.

- Husain, Khurram. 2017. “Exclusive: CPEC Master Plan Revealed.” Dawn, June 21.

- International Crisis Group. 2018. “China-Pakistan Economic Corridor: Opportunities and Risks.” Asia Report N°297. Brussels. doi:10.1163/2210-7975_HRD-9812-20180031.

- Irfan, Muhammad. 2019. ”PARC, GFRI China arranges training programme of trout fish farming business.” UrduPoint,accessed 19 January 2021. https://www.urdupoint.com/en/agriculture/parc-gfri-china-arranges-training-programme-713207.html

- ITC Trade Map. n d. Database Compiling Data from Pakistan Bureau of Statistics and UN Comtrade. Accessed 21 January 2021. https://www.trademap.org .

- Jahangir, Asifa, Omair Haroon, and Arif Masud Mirza. 2020. “Special Economic Zones under the CPEC and the Belt and Road Initiative: Parameters, Challenges and Prospects.” In China’s Belt and Road Initiative in a Global Context: Volume II: The China Pakistan Economic Corridor and Its Implications for Business, edited by Jawad Syed and Yung-Hsiang Ying, 289–328. Palgrave Macmillan Asian Business Series. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-18959-4.

- Jones, Lee, and Jinghan Zeng. 2019. “Understanding China’s ‘Belt and Road Initiative’: Beyond ‘Grand Strategy’ to a State Transformation Analysis.” Third World Quarterly 40 (8): 1415–1439. doi:10.1080/01436597.2018.1559046.

- Kamani, Sumaiya. 2019. “Cherry Export to China – Just One Step Away.” The Express Tribune, July 5.

- Karrar, Hasan H., and Till Mostowlansky. 2018. “Assembling Marginality in Northern Pakistan.” Political Geography 63: 65–74. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2018.01.005.

- Karrar, Hasan H. 2019. “In the Shadow of the Silk Road: Border Regimes and Economic Corridor Development through an Unremarkable Pakistan-China Border Market.” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 39 (3): 389–406. doi:10.1215/1089201X-7885345.

- Karrar, Hasan H. 2021. “The Power of Money: Chinese Investments and Financialization in an Asian Hinterland.” American Behavioral Scientist 000276422110200. doi:10.1177/00027642211020062.

- Khalique, Muhammad, T., Khushbakht Hina Ramayah, and Abdullah Farooq. 2020. “CPEC and Its Potential Benefits to the Economy of Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan.” In China’s Belt and Road Initiative in a Global Context: Volume II: The China Pakistan Economic Corridor and Its Implications for Business, edited by Jawad Syed and Yung-Hsiang Ying, 117–130. Palgrave Macmillan Asian Business Series. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-18959-4.

- Khan, Zulfiqar Ali. 2019. “Gilgit-Baltistan at the Crossroad of CPEC: Part I.” Pamir Times, June 24.

- Khawar, Hasaan. 2017. “The Real CPEC Plan.” Daily Times, May 27.

- Kiani, Khaleeq. 2019. “China Commits $1bn for 20 Social Sector Projects.” Dawn, March 8.

- Kreutzmann, Hermann. 2015a. “Boundaries and Space in Gilgit-Baltistan.” Contemporary South Asia 23 (3): 276–291. doi:10.1080/09584935.2015.1040733.

- Kreutzmann, Hermann. 2015b. Pamirian Crossroads: Kirghiz and Wakhi of High Asia. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Kreutzmann, Hermann. 2020. Hunza Matters: Bordering and Ordering between Ancient and New Silk Roads. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Kreutzmann, Hermann. 2006. “High Mountain Agriculture and Its Transformation in a Changing Socio-Economic Environment.” In Karakoram in Transition: Culture, Development, and Ecology in the Hunza Valley, edited by Hermann Kreutzmann, 329–358, Karachi: Oxford University Press.

- Lai, Karen P.Y., Shaun Lin, and James D. Sidaway. 2020. “Financing the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI): Research Agendas beyond the ‘Debt-trap’ Discourse.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 61 (2): 109–124. doi:10.1080/15387216.2020.1726787.

- Lim, Alvin Cheng-Hin. 2019. “The Moving Border of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor.” Geopolitics 24 (2): 487–502. doi:10.1080/14650045.2017.1379009.

- McCartney, Matthew. 2020a. “The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC): Infrastructure, Social Savings, Spillovers, and Economic Growth in Pakistan.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 1–32. doi:10.1080/15387216.2020.1836986.

- McCartney, Matthew. 2020b. “The Prospects of the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC): The Importance of Understanding Western China.” Contemporary South Asia 19. doi:10.1080/09584935.2020.1855112.

- Pamir Times. 2019. “Administrative Reforms: Gilgit-Baltistan Govt Issues Notification of Four New Districts.” Pamir Times, June 18.

- Pilardeaux, Benno. 1997. “Agrarian Transformation in Northern Pakistan and the Political Economy of Highland-Lowland Interaction.” In Perspectives on History and Change in the Karakorum, Hindukush, and Himalaya, edited by Irmtraud Stellrecht and Matthias Winiger, 43–56. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe.

- Planning Commission. 2020. A 2nd Meeting of Joint Working Group (JWG) on Socio-Economic Development under CPEC Framework. Islamabad: Press Release of the Planning Commission of Pakistan. November 4.

- Poerting, Julia. 2017. “Soziale Innovation Oder Business as Usual? Zertifizierte Bio-Landwirtschaft in Nordpakistan.” Geographische Zeitschrift 105 (2): 104–124.

- Produce Report. 2019. “Analysis and Forecast for China’s Tree Nut Sector in 2019/20.” Produce Report, accessed 29 January 2021. https://www.producereport.com/article/analysis-forecast-chinas-tree-nut-sector-201920 .

- Rippa, Alessandro. 2019. “Cross-Border Trade and ‘The Market’ between Xinjiang (China) and Pakistan.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 49 (2): 254–271. doi:10.1080/00472336.2018.1540721.

- Rippa, Alessandro. 2020a. Borderland Infrastructures: Trade, Development, and Control in Western China. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Rippa, Alessandro. 2020b. “Mapping the Margins of China’s Global Ambitions: Economic Corridors, Silk Roads, and the End of Proximity in the Borderlands.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 61 (1): 55–76. doi:10.1080/15387216.2020.1717363.

- Saeed, Aamir. 2019. “Chilgoza Prices in Pakistan Go Nuts as Exports Soar.” Arab News Pakistan, November 17.

- Shafqat, Saeed, and Saba Shahid. 2018. China Pakistan Economic Corridor: Demands, Dividends and Directions. Lahore: Centre for Public Policy and Governance, Forman Christian College.

- Sharp, Emma Louise. 2018. “(Re)assembling Foodscapes with the Crowd Grown Feast.” Area 50 (2): 266–273. doi:10.1111/area.12376.

- Sher, Ali, Saman Mazhar, Azhar Abbas, Muhammad Iqbal, and Li. Xiangmei. 2019. “Linking Entrepreneurial Skills and Opportunity Recognition with Improved Food Distribution in the Context of the CPEC: A Case of Pakistan.” Sustainability 11 (7): 1838. doi:10.3390/su11071838.

- Spies, Michael. 2019. Northern Pakistan: High Mountain Farming and Changing Socionatures. Lahore: Vanguard Books.

- Spies, Michael, and Henryk Alff. 2020. “Assemblages and Complex Adaptive Systems: A Conceptual Crossroads for Integrative Research?” Geography Compass 14 (10): e12534. doi:10.1111/gec3.12534.

- Spoor, Max, Xiaoping Shi, and Pu. Chunling. 2015. “Small Cotton Farmers, Livelihood Diversification and Policy Interventions in Southern Xinjiang.” In Rural Livelihoods in China: Political Economy in Transition, edited by Heather Xiaoquan Zhang, 131–150. Oxon and New York: Routledge.