ABSTRACT

There is a cyclical nature to the dilemmas confronting international donors willing to operate in Myanmar. Brief periods of relative openness led to rapid surges in development assistance, regularly interrupted by long phases of military rule and disengagement by donors. Amidst all this, many predicaments remain. This article engages with one of them: the inequality between regions. How have international donors reacted to the issue of domestic regional inequality? Recent studies suggest that official development assistance (ODA) does not target poor regions very well, but it is not always clear why this is the case. Myanmar’s sudden, yet uneven and unequal liberalization from 2011 to 2021 catalyzed huge inflows of ODA, while it also confronted donors with new policy dilemmas. The article shows that aid providers struggle with the problem of rising regional inequality, especially for political reasons. Donor and recipient interests often do not align well on this issue. In the case of Myanmar, donors who press for regional inequality to sit prominently on the agenda might fare less successfully than those who address the issue indirectly. The article concludes that regional inequality and the politics of targeting deserve a more central role in the political economy of ODA.

Introduction

Inequality between the regions of a country (“domestic regional inequality”) can have tremendous political consequences. It reinforces and exacerbates divides along “urban” vs “rural” or “central” and “peripheral” lines, especially in developing countries. Regional divides can be regarded as “meta-divides” since they often contain differences in income, culture, and social structures. Scholars have shown that regional inequality has significant implications for grievances, conflicts, and political contestation (Alesina et al. Citation2016; Cederman et al. Citation2011; Østby et al., Citation2009) and where there are conflicts over territory and the exploitation of resources (Bates Citation1983; Berkowitz Citation1997).

Against this background, the role of Official Development Assistance (ODA)Footnote1 in mitigating or exacerbating regional inequality is a topic of growing importance. While traditionally the academic literature has focused on the relationship between ODA and growth and poverty (Sumner and Glennie Citation2015), in recent years more fine-grained data have allowed scholars to delve into the domestic distribution of ODA (Bluhm et al. Citation2018; Briggs Citation2017; Nunnenkamp et al., Citation2017). One finding of this literature is that for many countries ODA tends to flow to relatively richer regions and hence shows problems in targeting poorer ones (Manuel et al. Citation2019). Overall, a better understanding of when and why aid agencies struggle with addressing regional inequality is necessary.

In this article, we use MyanmarFootnote2 as a case study to investigate these questions. Myanmar is a particularly instructive case because of the fast political changes between 2011 and 2021 and their implications for the aid sector. Although generally presented as a “transition”, the process was contested, uneven, unequal, and so was its labeling (Stokke and Soe Myint Aung Citation2020).Footnote3 An assessment of what happened needs to be situated as this was deeply racialized and gendered, with hierarchies and violent exclusions apparent even within the dominant Buddhist-Bamar core (Campbell and Prasse-Freeman 2022; Stokke and Soe Myint Aung Citation2020; Hedström and Olivius, Citation2022). This “transition” triggered both a dramatic socio-economic transformation and a substantial inflow of ODA as sanctions were lifted and debt forgiven (Bissinger Citation2017; Holliday and Zaw Htet Citation2017; Fumagalli Citation2022b). Reversing the relatively long and strong isolation from the world markets created a time-lapsed version of processes that are usually much slower and more difficult to observe. Myanmar is also a notoriously difficult case for rolling out aid to the periphery, with its long heritage of resisting centralization (Carr Citation2018; International Crisis Group [ICG] Citation2002, Citation2004; Meehan and Sadan Citation2018; Scott Citation2009), its decades-long ethnic armed insurgencies (Callahan Citation2003; Parks et al. Citation2013; South Citation2008) and a model of “ceasefire capitalism” modeled around resource extraction (Hardaker Citation2020; Kramer Citation2021; Woods Citation2011, Citation2019).Footnote4

Our findings contribute to the existing literature on the domestic distribution of ODA and the politics of aid targeting. While most studies focus on project aid, we also look at the overall balance of aid flows, as project aid is often dwarfed by other forms of assistance. We also explore the ways in which major donors interact with the recipient government. Given that it is the main gateway for aid in a contested political territory, international donors need the consent of the recipient government.Footnote5 Thus, explicit forms of targeting might backfire if they were to be perceived by the central authorities as politically motivated. In our research we draw on quantitative and qualitative methods to explore both the evolution of aid flows to the country, paying attention to both traditional and new donors (Japan, South Korea, the United Kingdom and Germany). We complement this analysis with a case study on higher education reform lead by a non-state donor in which we were also involved and about which we conducted interviews between 2013 and 2022.

The article’s main contention is that international donors struggle with regional divergence not only for logistical but also for political reasons. Donor and recipient interests often do not align well on this issue. In the case of Myanmar, donors who press for regional inequality to sit prominently on the agenda might fare less successfully than those who address the issue indirectly. While donors alone hardly account for the rising inequality, the substantial aggregate aid flows do little to mitigate it. Only in recent years have we seen efforts to counter this imbalance. One of the problems lies with conflicting donor motives. While most donors now have rural development as one of their priority areas, rolling aid out to the “periphery” remains challenging and not always advantageous for these regions in practical as well as political terms (Carr Citation2018; International Crisis Group (ICG), Citation2002). The second and related reason lies in the recipient’s interests: in the context of a highly centralized government, large portions of international aid gravitate toward central regions. Where donors explicitly try to target others, they will face resistance from the recipient’s side.

The period we focus on in this article covers the decade of sudden and short-lived and partial political opening between 2011 and 2021. We will not cover the period from 1 February 2021 onwards, when a coup by the Myanmar military brought an end to the changes introduced over the previous decade (Fumagalli Citation2022a; Loong Citation2021). The coup itself might have been partly – among other things – the consequence of regional polarization and contestation, but it represents a clear break as most western donors have stopped providing ODA to Myanmar.

The article proceeds as follows. First, we discuss our methodology and positionality in doing research in Myanmar. Next, we survey the scholarly literature on regional inequality and the role of ODA. Subsequently, we look at the Myanmar case and discuss important contextual factors. In the remainder of the article we examine the quantitative evidence for the relationship between aid flows and regional inequality, before delving in greater depth into the examples of a select number of donors. The final section concludes with some general implications of our findings.

Positionality, methods, and data

Research in authoritarian and conflict settings confronts scholars with a particular set of challenges and responsibilities. In our work we are followed best practices as discussed in anthropology (Chattopadhyay Citation2013), sociology (Wackenhut Citation2018) and geography (England Citation1994; Koch, Citation2013), as well as political science (Knott Citation2019; Malejacq and Mukhopadhyay Citation2016; Fumagalli and Rymarenko Citation2022; Fumagalli Citation2023). The Burmese Studies scholarship has been particularly attentive to issues of decolonization and neo-coloniality in the study of Burma/Myanmar, including in relation to sources, methods and collaboration with local scholars (Brooten and Metro Citation2014; Metro Citation2019; Tharaphi Than Citation2021; Chu Main Paing and Than Toe Aung, Citation2021; Hedström Citation2019; Décobert Citation2014), cautioning against “white saviourism” (Calabrese and Cao, Citation2021; Maung Zarni, Citation2021) and neo-coloniality in research (Chu May Paing and Than Soe Aung Citation2021; Phyo Win Latt Citation2011; Tharaphi Than Citation2021). This important strand of the literature also advised against a casual engagement with local authors, scholarship and sources (Charney, Citation2021a, Citation2021b).

As white male scholars from Global North institutions, we are aware that our position in Myanmar came with considerable privilege. Privilege, “a matter of social power and political differentiation” (Kappler, Citation2021, 422), is a condition that international researchers – especially white, especially from the Global North – often enjoy (McCorkel and Myers Citation2003). For a start, entry and exit were reasonably unproblematic for us, as we could rely on the support of local academic institutions and the Ministry of Education for relevant visa support. This was the case both during the Thein Sein administration (our visits began in 2013) and during the NLD government (our last visit was in 2019). Exit or even intra-country mobility were privileges not afforded to our local academic colleagues, who had to apply to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to release their passports for international visits to our former institution in Europe (which had a large institutional agreement with Myanmar’s universities). Another issue was that of the status attached to our role. Although our research on international aid was supported by other institutions, especially during the 2015–2022 period, our initial access to the country and engagement with local universities was facilitated, indeed enabled, by a large non-state donor, which from 2013 onwards became a major source of support for higher education reform in the country. This carried a high risk of being identified as donors ourselves or being able to influence the donor’s funding decisions (both assumptions were incorrect). We were very clear at all times that this was not the case, being conscious of the serious and unethical risk of mis-identification (Tewksbury and Gagné Citation1997). We see our own stance as one of “positioned interpretation” (Mosse Citation2006, 941 and Décobert Citation2020). We position ourselves as part of the project we designed and helped implement and are responsible for its contributions and its failings.

To examine how aid agencies address the issue of regional inequality, we draw on three different empirical sources. Quantitatively, we compiled a data set on aid flows to Myanmar’s regions,Footnote6 geocoding ODA flows regionally over some 20 years. We briefly compare these data with the data on regional inequality based on satellite images to see whether aid flows have responded to the skyrocketing levels of regional inequality in recent years (see Appendix C). Next, we review the rhetoric and practices of four other bilateral donors (Germany, South Korea, Japan and the UK) to understand the degree to which donors respond to regional inequality and whether different donors respond differently. We decided not to include two other major bilateral donors (US, Australia) as they are somewhere in the middle of the pack when we look at regional shares, giving clearly more to regions than a donor like South Korea, and decidedly less compared to Japan or Germany (see Appendix A, below). Consequently, they would not add much variation to our comparison. An exception might be China, but it has been extensively discussed in the literature including in relation to Myanmar (Reilly Citation2013; Steinberg and Fan Citation2012; Kiik, Citation2016; Rippa Citation2020; Calabrese and Cao, Citation2021). Data on Chinese aid flows are also challenging to compare to those of western donors. Third, we also rely on our own observations and interviews carried out during multiple visits to Myanmar between 2013 and 2019 for periods between two and eight weeks a year, to highlight the limits of donor agency and to tease out the role and agenda of the Myanmar government. Additional visits were made by Fumagalli to Bangladesh (Cox’s Bazar) in 2020 and Thailand (Chiang Mai) in 2022, as he has been involved in research on refugees, conflict and cross-border aid in the educational sector on both sides of the Myanmar border. Altogether, we conducted 24 interviews with representatives of international donors, local academics and experts (see Appendix B).

An additional note on terminology and data is also in order, as we see honesty and transparency with data limitations as crucial to the process of knowledge production. While in our paper we appear to rely on “hard (statistical) data” also, we do so with the awareness that data are never neutral nor speak for themselves. This is nowhere more evident than in Myanmar. Our units of analysis are the administrative units in Myanmar (seven States, seven Regions, and the capital Nay Pyi Taw). The challenge in this regard is thus two-fold: one, getting “precise numbers”, because the Myanmar government does not reveal census data on ethnicity in each state and division. And two, problematizing those numbers given that ethnonyms such as “Karen” mean different things to different people at different times in different locations (Décobert Citation2020; Décobert and Wells Citation2020; on other groups and the historical context behind classification see Ikeya Citation2020 and Candier Citation2019). The same point of course applies to the case of the Kachins (Sadan Citation2013), as there are Kachins outside of Myanmar’s Kachin State, and outside Myanmar for that matter. Furthermore, ethnic Bamars live in Kachin state too, especially in the relatively larger urban centers (Sadan Citation2013). The Kachin war itself is less about Kachin State as such, as much fighting takes place in Northern Shan State. Last, but not least, the terms “nation” and, concomitantly, “subnational” to refer to domestic regional inequality, while common in the aid literature, are controversial and contested in the Myanmar context. It is therefore important to use terms such as “periphery” with extreme caution. Our intention is not to reify politically loaded concepts in a geographic or ethnic dimension. To the contrary, the idea of a “Bamar centre” roughly consistent with the Irrawaddy basin and a “non-Bamar periphery” is itself a historical construct (Charney Citation2009, especially chapters 1&2) to a large extent created by British colonialism and then perpetuated after independence.Footnote7

The problem of regional inequality and the role of ODA

The regional dispersion and distribution of aid is a long-standing topic of academic and practical relevance. A considerable portion of the economics (Mekasha and Tarp Citation2013; Sumner and Glennie Citation2015) and politico-economic literature (Bueno de Mesquita and Smith Citation2009; Neumayer Citation2003) has traditionally focused on the international distribution of aid. Recently, the better availability of geocoded information on ODA has allowed academics also to investigate the internal distribution of ODA within countries (Bluhm et al Citation2018; Briggs Citation2017).Footnote8

A strikingly consistent finding in this literature is that ODA flows to richer rather than poorer regions within a country. For instance, Öhler and Nunnenkamp (Citation2014) have looked at the geographic distribution of World Bank and African Development Bank projects. For a set of 27 recipient countries they found that measured “needs”, such as high infant mortality, matter little in the distribution of project aid (Öhler and Nunnenkamp, Citation2014). Other studies concur (Briggs Citation2018).

Hence, within-country regional inequality is politically very salient, but project aid flows, it seems, do little to reduce inequality. This contrast motivates our research interest. How do aid agencies respond to regional divergence? Do they actively try to counterbalance regional polarization, or perhaps rather unknowingly reinforce it? To the best of our knowledge, scholarly research directly contributing to this is scant in number, but can make use of an extensive literature on “aid flows” between countries and domestic aid flows within countries.

First, bi- and multilateral donor initiatives have focused on poverty reduction in recent years. This should mean that aid flows to both the poorest people and the poorest regions. Yet for political reasons, the effectiveness and salience of poverty orientation in ODA has varied over the last decades (Bodenstein and Kemmerling Citation2015; Briggs Citation2017). For instance, a poverty orientation in ODA was very prominent in the 1950s and 1960s, but it only really came back in the early 2000s. In other decades, the focus on economic growth often prioritized economic hotspots while neglecting remoter, less productive regions.

There are well-known trade-offs in targeting the poor and poor regions (Besley and Kanbur Citation1990; Sumner Citation2012). Drawing on the literature about the determinants for the international distribution of aid, poverty and need are rarely the only or even the major concerns (Alesina and Dollar Citation2000; Bueno de Mesquita and Smith Citation2009). We do find similar results for the role of domestic or supranational forms of regional policy and aid (Kemmerling and Bodenstein 2006; Bodenstein and Kemmerling Citation2012; Arulampalam et al Citation2009). This literature discusses the role of internal inequality in the distribution of aid flows. For instance, De la Fuente and Vives (Citation1995) examine the importance of equity vs efficiency criteria for the distribution of regional transfers and find that equity concerns matter relatively little. Even when donors emphasize the necessity of targeting poor regions and address the problem of regional inequality, the recipient’s motives also need to be aligned. Otherwise, donors face a dilemma: if they focus explicitly on regional imbalances of aid and try to target specific regions, the recipient might reject the intervention. Hence, there is a convoluted bargaining regarding what is acceptable for both sides, especially if the recipient is confronted with political problems of regional polarization. An extreme example is the problem of aid interventions in countries with ongoing violent conflicts. If donors press hard and explicitly against regional imbalances, this could increase the recipient’s resistance (Swedlund Citation2017) to let the donor channel money into “sensitive” regions.Footnote9

In this article, we show that the politics of targeting and the dilemmas associated with it are major reasons for when and how ODA will respond effectively to regional inequality. Donors have to balance the focus on poverty reduction and rural development with issues of practicality and the strategic interests that donors and recipients have. This prompts the empirical question of how donors react to regional inequality and difficulties in delivering aid to particularly poor domestic regions. Do donors perceive regional inequality to be a major concern? How do they even define or see regional inequality? And do they shift their aid strategy to specific topics (such as human rights, agriculture), specific sectors (basic assistance), or specific forms (project aid or humanitarian aid) to respond to regional inequality?

Myanmar as a case study of regional inequality

Myanmar is a particularly instructive case study to answer these questions because of its internal variation: some regions are harder to access than others, conflict areas shift over time, and there are long-standing politicized ethnic cleavages. Moreover, the drastic economic and – to some degree – political opening came suddenly in 2011 and ushered in a time-lapsed socio-economic transformation of the country (Asian Development Bank Citation2017; David and Holliday Citation2018; Thant Myint-U, Citation2019), while the political change itself proved to be superficial and short-lived (Campbell and Prasse-Freeman Citation2022). Nonetheless, such dynamics allowed for an enormous inflow of ODA from both Western and Asian donors (Carr Citation2018; Reiffel and Fox Citation2013). The abrupt and rapid pace of these changes allows us to investigate the mutual relationship of ODA and regional inequality more clearly than in countries where such processes happen much more gradually.

To understand how ODA relates to regional inequality today, we need to briefly consider the country’s historical context. Regional inequality and tensions between different regions run throughout Myanmar’s history. The agriculturally productive zones along the Ayeyarwady River have always been an attractive resource for local rulers and powerful neighbors (Harvey Citation2000; Scott Citation2009).Footnote10 British colonial rule and the immediate aftermath of World War II reinforced regional divisions and cemented the idea of two Burmas: a predominantly Bamar mainland under direct British control (“Ministerial Burma”) and the “Frontier Areas” endowed with greater autonomy (Charney Citation2009; Prasse-Freeman and Phyo Win Latt Citation2017; Thant Myint-U, Citation2001). Though intuitive and appealing in many respects views based on binaries (core versus borderlands) need some serious historical contextualization. Myanmar is home to several competing nation-building projects, but also several competing state-making ones, and there are multiple differences among the country’s many peripheries (Meehan and Sadan Citation2018). Crucially, there are also significant differences and hierarchies (racial, gender, class, ideological) in the core (Jordt, Than, and Lin 2021; Htet Min Lwin Citation2021). Actually, some of the divisions were and continue to be less regional than they are ethnic.Footnote11 The Karens, the Mons and the inhabitants of Rakhine were not under the Frontier Areas, but were governed as part of Ministerial Burma. The highly centralized military governments after World War II governed the Bamar mainland and some remoter areas, while other areas such as Rakhine and Kachin states, among others, remained contested, home to alternative, non-state forms of governance. Even the decade from 2011 to 2021 did not bring the country any closer to peace. To a large degree, the political change exacerbated inequalities in wealth and the extraction of rents in an already highly unequal country (Campbell and Prasse-Freeman Citation2022; Calabrese and Cao, Citation2021). Thus, a nuanced understanding of Myanmar needs to refrain from excessively state-centric perspectives.

Some these binaries have tended to endure and have been even reinforced by the aid industry itself: a case in point is the dilemma in aid provision, because, by and large, donors need to pass through the gateway of the “dominant” nation-building project run by the internationally recognized sovereign government of Myanmar and its regime. In the Myanmar context, as examined by Décobert (Citation2020 and 2021), Nilsen (Citation2020), and Jung (Citation2020), there has been a divide between development and humanitarian aid, with the latter going to community organizations in border and cross-border regions. State- and nation-building remain Myanmar’s long-standing and unresolved challenges. Such adversities also left their mark on the massive and increasing regional inequality.

Bearing all these caveats in mind, even brief experiences of traveling outside the largest cities reveals huge gaps in infrastructure and the provision of public services. Yet, even with all the cautioning against simplified dichotomies mentioned above, lends some support to this notion of “two Burmas” in which (economic) activity seems concentrated in the Bamar mainland, with other regions seeing hardly any of it.Footnote12

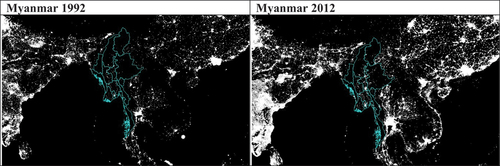

Figure 1. Change in nighttime luminosity between 1992 and 2012.

The maps above show data on nighttime luminosity in Myanmar for two years, 1992 and 2012.Footnote13 The blue boundaries demarcate the states and divisions in the country. Even a cursory glance reveals three basic facts. First, Myanmar shows very low levels of nocturnal electricity consumption. This is true even when comparing its consumption levels to other poor countries in its neighborhood. Second, there are big differences between the Bamar mainland along the Ayeryarwady River (especially in the three main cities Yangon, Nay Pyi Taw and Mandalay) and the border regions. Third, these differences between the core and the periphery have increased over time: growing consumption mainly happens in the mainland, and specifically in the big cities.

While nighttime satellite data primarily show electricity consumption, it is also a valid proxy for measuring economic activity, especially for poor countries with unreliable administrative statistics (Henderson et al. Citation2012). Prospering economic regions, in turn, attract internal migration, and thus further exacerbate regional inequality. Based on these luminosity data, we can construct an index of regional inequality, measured as the standard deviation of average luminosity in each of the 15 regions. In Appendix A (Figure A2), we show some simple validity tests of the luminosity data with other sources of information. We also illustrate that Myanmar’s level of regional inequality is clearly severe but still not the extreme cases worldwide. This would suggest that the Myanmar case study holds interesting lessons also for other countries.

It is difficult to underestimate the growing salience of the regional differences in Myanmar, especially in terms of conflicts between a Bamar-dominated center and the horseshoe-shaped borderlands in which ethnic minorities predominantly live. As Jones (Citation2014) aptly put it, in Myanmar “the periphery is central”. What follows is that regional inequality has three dimensions that overlap to a significant degree. First, the difference between capital and periphery. Historically the capital has shifted around between Yangon, Mandalay and Nay Pyi Taw, but there is a clear difference between these places and the rest of the country. Second, the difference between urban and rural areas: the Ayeyarwady River area including the three main cities is much more densely populated than the rest of the country. Third, the difference between Bamar and non-Bamar regions with all the ethnic conflicts this entails. It is clear that these distinctions are not totally clear-cut, but they are politically salient and hard to disentangle from one other. The question remains how donors, or even the recipient government, responds to this complex domestic regional inequality in the context of ODA flows.

ODA in Myanmar

Aid flows did not just (re-)start with the political reforms of 2011. Some donors never really aligned themselves with the US (and EU) sanctions imposed following the military takeover of 1988 and the crackdown after the 1990 elections. In addition, Cyclone Nargis in 2008 provoked considerable inflows of humanitarian aid over a short period. Nevertheless, it is clear that the opening after 2010 paved the way for a dramatic increase in the number of donors, the size of the aid flows, and the number of interventions (Reiffel and Fox Citation2013). The most drastic change came in 2012 to 2013 when, according to the OECD Creditor Reporting System, aid commitments to Myanmar increased from less than one to almost seven billion USD (Carr Citation2018, 5).

To assess the role of ODA in mitigating or accelerating regional inequality, we mainly rely on OECD/DAC data. We extracted information for the largest bilateral donorsFootnote14 as well as the major multilateral ones.Footnote15 We also extracted information for Chinese aid flows from the website aiddata.org, but given its limited reliability and comparability, we used these data only as a memorandum item.Footnote16 We selected states and divisions and the capital as union territory as the level of geographic disaggregation mainly for pragmatic reasons of data availability, but also because the power balance between these units is a politically salient topic for the federalism of the country.

Putting all this information together yielded around 9,000 aid interventions between 1995 and 2015. We used the descriptions to code the geographic target destination in each intervention. Initially, we relied on human coding. In less than 15% of all cases, this yielded clear information about whether the intervention targeted one of the states and divisions or the central government. Therefore, we computer coded all those remaining interventions for which we did not have information with a battery of search strings. For instance, we coded rural projects where we found such terms in the project descriptions. We added to this category interventions that had the official Creditor Reporting System sectoral code for the primary sector (see Appendix A for details).

In total, we found reliable geographic information for almost 70% of all projects. As for the remaining cases for which no information was available, several possibilities remain. Either we could not allocate these projects according to any geographic criteria, or the criteria were not applicable (for example when money was dispersed to Burmese student scholarships abroad). A third possibility was that of multiple destinations of aid flows. We coded such projects with multiple destinations separately, but they resulted in a small fraction of the overall codings. Most of those projects for which we had no direct information arguably were destined for central government purposes. In this sense, our estimates of the regional share of ODA projects are an upper bound on the real (direct) regional share of all ODA projects and they (still) underestimate the share flowing to the central government.

To validate our results, we compared them with other sources. We used the official donor reports by the large donors and the Myanmar government for that purpose. Another important source for triangulation comes from a recent comprehensive survey of aid activities in Myanmar (Carr Citation2018). This detailed and meticulous survey computes the share of aid projects going to regions for one year only (2016), but the results for this year are very similar to results from our much simpler approach.

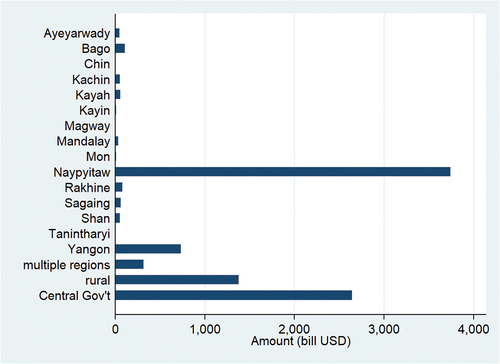

shows the dominance of the central government and capital city Nay Pyi Taw in receiving aid. Each bar represents the total sum of ODA inflow for the 20 years for which we had information. Out of a grand total of c.US$11 billion, the central government and the capital received about U$6.6 billion. Because Nay Pyi Taw is just the capital city of Myanmar, without much hinterland, it seems reasonable to lump ODA projects for the central government and for Nay Pyi Taw together. The region with the second largest aid inflows is Yangon, already below one billion USD. Rural development projects make up some US$1.4 billion.

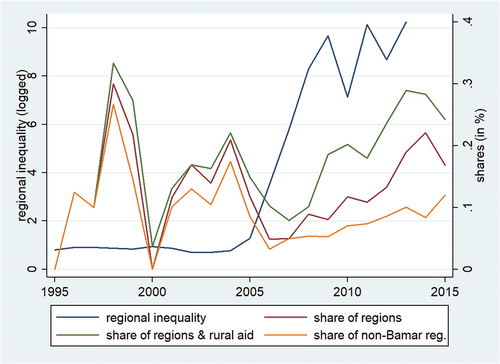

With these data, we have calculated three measures for the regional share of ODA for the 20 years between 1995 and 2015, focusing on the three dimensions of regional inequality mentioned earlier. shows the results for the regional shares. If we count only the share of all regions excluding the capital (“political center vs periphery”), the regional share spiked in the late 1990s, then fell and subsequently recovered to some 18% of all ODA in 2015. Adding all rural development projects (“urban vs rural”) which do not mention specific regions, we find similar movements ending in 2015 on a level of roughly 24% of all ODA. Finally, the share of money flowing to non-Bamar regions is much lower, hovering between 5 and 15% for most of the period.

It is clear that inequality in Myanmar has several causes (Prasse-Freeman and Phyo Win Latt Citation2017, 409) and has many dimensions – from gender (Hedström and Olivius, Citation2022) to settlement types and ethnicity. To measure the impact of aid on inequality does not deliver results with our, rather coarse data, but it arguably falls behind other forms of capital inflows (Bissinger Citation2017). But, we are mainly interested in the opposite direction: It seems clear that donor agencies reacted to regional inequality. The combined share increased once regional inequality exploded. And yet we also see that, on an absolute level, the share that went to regions was still dwarfed by the sums allocated to the central government, and that there were differences between Bamar and non-Bamar regions. In the next section, we zoom in further on some of the donor interventions to examine in more detail how these agencies have responded to rising inequality.

We included all (major) types of aid flows in the analysis. This means that financial aid, especially in the form of debt relief is counted as aid to the central government. While this is not always accurate, the lion’s share of debt relief is channeled to the central government. In Appendix A, , we see that for some donors debt and emergency relief are, indeed, the largest forms of aid giving. Hence, the spikes account for large forms of debt forgiveness in 2012 and 2013, which made subsequent increases in aid possible, as detailed in Carr (Citation2018). If we exclude debt relief from our analysis, the peaks are much smaller (they still happen because these years also showed big inflows of program and project aid), but the qualitative assessment of aid to regions vs. aid to the center remains.

How do donors respond to rising regional inequality?

In this section, we add qualitative evidence about whether and how aid agencies respond to regional inequality. To guide our reasoning, we explore three sets of questions. First, do donors talk about regional inequality, and, if so, how salient is it in the donor rhetoric? Second, does the money follow donor rhetoric (i.e. do flows also target more remote regions)? And, thirdly, what problems do donors confront when addressing regional imbalances? To answer these questions, we mainly used the donors’ official publications and complemented this information with (background) semi-structured interviews with representatives of donor agencies and Myanmar academics and experts.

We looked at different types of donors. Several authors have noted that aid giving in Asia differs in some ways from other regions. Stallings, (Citation2017), for instance, have argued that Eastern Asian donors, such as Japan, are very different from their Western counterparts (see also Arase Citation2005; Carr Citation2018; Dreher et al Citation2011). For instance, Japan never really severed ties with Myanmar despite the US-led sanctions (Strefford Citation2016, 489) so they could quickly reopen aid channels once the sanctions were lifted. Also, Asian donors, such as South Korea and Singapore, are more interested in fostering regional economic exchange and a model of the developmental state compared to “Western” donors (Stallings, Citation2017, 16). Thus, we selected donors representing such different types: an old donor with a relatively new interest in the country (Germany); a new, rising Asian donor (South Korea); a donor with a long history with the country (Japan); and a donor with a long history of involvement interrupted by the sanctions (the UK).

An analysis of the donors’ country strategy papers revealed that very few among them refer to inequality explicitly, but most mention problems of specific, remote, and rural regions, as well as poverty in such regions. Germany is a case in point. Its major development agency GIZ (Gesellschaft für interationale Zusammenarbeit) returned to Myanmar after a 20-year break imposed by the sanctions. GIZ mainly implemented Germany’s development initiatives, backed by the local embassy and commissioned by the Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development. GIZ’s priority areas were in the fields of education, sustainable economic development, and rural development.Footnote17 To help reduce poverty, GIZ primarily focused on developing the private sector, promoting the financial sector, and providing vocational training. The agency’s flagship projects were in aquaculture and electrification in rural areas. It is not always easy to break down aid data by a regional logic. When we look at our data, however, we do see that Germany’s share of aid going to regions was above average, hovering around 30% (see Appendix A, ). We also see that German donors often targeted aid to NGOs in aid flowing to the regions, arguably trying to bypass the central government (Appendix A, ).

While representatives of other donors noted the difficulty with disbursing funds and the low capacity of implementing projects, GIZ was more optimistic in this regard. GIZ deemed the local capacity in Myanmar to deal with aid relatively high.Footnote18 Neither did GIZ report any particular challenge when rolling aid to the periphery. In part, this could be the consequence of Germany’s aid not necessarily targeting borderlands per se and mainly focusing on relatively technical issues.Footnote19 The exception here was Shan state, where GIZ runs several aid interventions, such as investments in rural infrastructure.

Compared to Germany, the relatively new donor South Korea looked much less into the issue of regional inequality. South Korea’s development assistance to Myanmar was relatively small when compared to that of other East Asian countries but rapidly increasing (Fumagalli, Citation2017). The involvement of the Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA) in the country was wide-ranging, including support ($20 million) of the Myanmar Development Institute in Nay Pyi Taw to higher education projects with the University of Yangon as well as a $22 million-worth attempt to “export” Korea’s rural development experience through the New Village Movement (Saemaul Undong). Myanmar moved up in the priority list for aid recipient countries from being outside the top 20 in 2011 to number four in 2014.

KOICA cursorily mentioned the issue of inequalities among regions in its 2016 country strategy (KOICA Citation2017), but that was merely a short reference to the Myanmar government’s own economic policy document of 2016 (Government of Myanmar Citation2016). Meetings in both Seoul and YangonFootnote20 suggested that Korea was keener to follow other donors’ priorities than to promote an agenda of its own.Footnote21 In addition, the interviewees also emphasized that what matters to Seoul was to be aligned with the recipient’s interest. This was consistent with current donor practices that emphasized local ownership and coordination, and it effectively shifts the agenda setting to the recipient. A look at KOICA’s aid flows reflects this regional “indifference”, with most of the projects assigned to nationwide priorities (see Appendix A, ).

Saemaul Undong was a rather short-lived exception to the rule. It drew on and referenced Korea’s rhetoric of “sharing” its own development experience, which has become a mantra of Korea’s foreign economic and aid policies (Fumagalli Citation2017; D’Costa Citation2015; Heo and Roehrig Citation2014). Some of the more generous contributions in the sector of rural development in Myanmar drew on former President Park Geun-hye’s own “obsession” with restoring the legacy of her father – dictator Park Chung-Hee – by promoting Korea’s own rural village development model across Southeast Asia. Its applicability and relevance to the Myanmar context were disputed both by Myanmar’s authorities and Korea’s own development agency officials,Footnote22 and were abandoned after the influence-peddling scandals of 2016—which incidentally also had a Myanmar dimension (Kim, Citation2018)—and Park’s impeachment in 2017.

The two long-standing donors, Japan and the UK, seemed to be more clearly concerned with the geographic distribution of ODA but in very different ways. Japan has been present in Myanmar for several decades, beginning with reparation payments after World War II and leading to massive inflows of Japanese aid (Reilly Citation2013; Steinberg Citation1991). The Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) ran projects throughout the country, from Kayah to Kachin state (Carr Citation2018). Footnote23 As a consequence, the share of aid targeting regions and the rural sector was higher for Japan than for all other bi- and multilateral donors in the country (see Appendix A, ).

This high share going to regions seemed due to the high and uninterrupted levels of trust that Japan cultivated across all Myanmar authorities, which enabled JICA to operate in the borderlands. A review of the projects shows that – consistent with the broader aims and focus of Japan’s ODA policy (Arase Citation2005; Shimomura et al Citation2016)—the focus was on the promotion of local economic development through the support of infrastructural and energy projects. This focus seemed to make Japanese aid less politically sensitive for the Myanmar government. The regional focus, however, did not imply that money really benefitted the regions. The Baluchaung hydropower plants in Kayah state are a case in point. Kayah state is certainly in one of Myanmar’s poorest states; however, the projects employed very few locals, and the benefits for local communities and vulnerable people were unclear (Carr Citation2018, 12).

Compared to Japan, the UK – Myanmar’s second-largest bilateral donor – took a more explicit stance on the matter. The UK’s top priorities were comparable to those of other donors and included issues such as promoting good governance, inclusive growth, as well as peace building and national reconciliation. In addition, the UK also explicitly targeted “areas and groups affected by conflict which are deliberately disadvantaged” (DfID 2018, 2). The Department for International Development (DfID) further specified that this entailed “a geographical focus on the ethnic/border states” (DfID 2018, 2). Such an approach was unusual among larger donors, and it constituted a clear break with the British approach to Burma in colonial times. In practice, this meant that DfID closely monitored the situation in conflict-ridden Rakhine, Kachin, and Shan states.

The question, however, is whether DfID was successful in targeting poorer and conflict-ridden ethnic regions in Myanmar. Between 1995 and 2015, the majority of DfID money mainly benefited central destinations (see Appendix A, ). Nonetheless, within the relatively small regional share, DfID did target mainly non-Bamar regions. For instance, some of the largest UK aid projects target emergency help in Rakhine state. Before the coup, the UK had 27 active projects with a specific or even exclusive focus on the borderlands. Only the “supporting peace-building in Burma” (identifier GB-1 -204,661, total budget just under £32.5 m)—the UK’s efforts to build the capacity of civil society, women, youth, and religious and ethnic communities through the Paung Sie Facility – was an exception, as the organization has worked across the country.

Of course, the overall low share to regions might be due to other reasons. For instance, the UK might have simply place more emphasis on the central government’s ownership or try to indirectly reach remoter regions by other means such as targeting sectors rather than regions. Nonetheless, the discrepancy between donor intentions and donor aid allocations suggests that donor rhetoric might sometimes create obstacles to targeting poor regions. Donors face issues in openly tackling regional inequality if they are confronted with a recipient for whom this interference is a political challenge. Donors using an indirect approach targeting specific sectors, such as Germany or Japan, might have more impact than donors that have an explicit approach. However, this comes with further costs such as relying on “non-political” aid and without control over where benefits of interventions eventual accrue. To illustrate this political dilemma further, we now switch to the perspective of the Myanmar government.

The recipient’s role: The case of reforming higher education in Myanmar

Given the politically sensitive nature of the topic, we could not directly interview government officials. What we instead use as empirical evidence comes from an aid intervention on a much smaller scale. We participated in a project of the Open Society Foundations’ (OSF) International Higher Education Support Programme (HESP). The project began in 2013 and ended in 2016.

The OSF project was the response, first, to the invitation of the U Thein Sein administration (Farrar (Citation2013; IIE Citation2013) and, later on, the government led by the National League for Democracy (Government of Myanmar Citation2016). In this respect, the “opening of educational space” (IIE Citation2013, 5) was a fragile policy window for reform in the country (see Lall Citation2020: 16). The higher education system was derelict, underfunded, and poorly managed under the previous military regime (Esson and Wang Citation2018).

The curtailing in size and autonomy of higher education institutions was a deliberate reaction of the military regime to the student uprising of 1988 (Lall Citation2020, 132). The 1988 uprising led to the dismembering of the University of Yangon, with the opening of campuses in more remote parts of the city. The programmes most affected were all in the social sciences, an area the military government deemed to be breeding social unrest. It seemed a key priority for the National League of Democracy to reestablish the status of Yangon University as one of Southeast Asia’s gems of higher education.

The project’s focus was threefold: first to assist university and departmental leadership with curriculum reform and development and to work alongside individual staff on course development and issues pertaining to pedagogy through the introduction of new approaches to teaching and learning. This led to the reopening of undergraduate programmes in international relations at the University of Yangon after a hiatus of 25 years (since 1988) and later at the University of Mandalay, as well as the launch of new undergraduate programmes in political science at both universities.Footnote24

Given that the highly centralized Myanmar government was mainly interested in creating national champions, the issue of regional inequality (between universities in Yangon/Mandalay and the rest of the country) featured neither in the project nor in the country’s general higher education reform. Stepping up the capacity of other universities, especially those in the borderlands, was neither a consideration for the government (Sadan Citation2014), nor for the donor as a consequence. In fact, the project was representative of broader international involvement in the country from 2011 onwards in that it was very much Yangon-centric, with the University of Yangon receiving most of the attention (Esson and Wang Citation2018; Phyu Thin Zaw Citation2017).

Spill-over effects only happened indirectly and unintendedly. One key feature of Myanmar’s highly centralized system in higher education helped the project’s “regional balance”. The central administration uses a policy of staff rotation, whereby faculty members are reassigned to different universities every four years or so. Such a turnover in staff allows the ministry to control universities to a large degree, but it also effectively means that potential investments in human capital will also be spread throughout the country. Due to this staff rotation policy, there were minor trickle-down effects of the OSF intervention to less-renowned institutions in Yangon, Mandalay, and beyond. Over time, and actually thanks more to word of mouth than a strategic approach on anyone’s side, faculty from other neighboring universities were invited to the workshops and began introducing some of the changes discussed during those events.

To summarize this rather small case, the Myanmar government did not have much interest in countrywide engagements that would actively seek the participation of universities beyond the Bamar heartland of Yangon and Mandalay (Sadan Citation2014). The ministry of higher education had other priorities, as evidenced by its statements, education reviews, and development plans for the higher education sectors. The University of Yangon, and to a somewhat lesser degree the University of Mandalay, were to be the priority. The donor, in turn, largely wanted to ensure the government’s ownership of the project. This was consistent with the emphasis in the aid industry on “local ownership” but also with the fear that otherwise the Myanmar government would have stopped the project.

Drawing on this brief qualitative exploration, we can now also see the donors’ dilemma in problematizing regional inequality. Against the background of a highly centralized recipient acting as gatekeeper, very few donors explicitly mention politically sensitive topics. Many do try to shift money into disadvantaged regions, either directly or indirectly. The exception here may be Korea, which maps most closely to the recipient’s interests. However, there are clear trade-offs. For instance, the Japanese (and perhaps German) route of focusing on relatively technical issues made it easier for them to reach remoter areas. This also often implies that the concrete benefits for the regions are unclear. In contrast, the UK exhibited a more explicit donor rhetoric, with a specific focus on non-Bamar regions, but then it faced problems in actually rolling out the money to the regions. A large part of the issue hence lies on the recipient’s side. Despite the political opening till 2021, Myanmar’s authorities still heavily guarded the regional redistribution of aid in the country.

Conclusion

Through a discussion of how both the national government and a select number of donors dealt with the question of regional inequality we contribute to the scholarly and policy discussions on the role of development assistance in addressing this issue. While regional inequality is an increasingly salient topic in many developing countries, international donors still need to pay more attention to it.

We used the case study of Myanmar to illustrate how the rapidly increasing regional disparity within the country puts the industry of development assistance under severe pressure. On the one hand, vulnerable target communities often live in the most peripheral regions; on the other, donor and recipient’s motives do not always align well enough to ensure an accurate targeting of this population.

An analysis of the geocoded aid interventions of major donor agencies in Myanmar over twenty years shows no strong trend toward poorer regions. There is some evidence that ODA donors have reacted to increased regional inequality in the most recent years, but aid flows still largely benefited central regions, especially if we look at all types of aid and not only project aid. Looking more closely at the discourse and practices of several donors, we identified some reasons why this is the case. Contrasting the UK experience with Germany and, in particular, Japan on the one hand and the South Korean experience on the other, we found that indirect ways of targeting (for example through specific sectors) can be more effective than explicitly targeting the periphery, where most of the ethnic minority groups are concentrated. Japan mainly relies on technical forms of aid and reaches more of the remoter areas, although it is not clear to whom the benefits really accrue. The experience of OSF’s involvement in Myanmar’s higher education reform confirms how difficult it is to address regional imbalances if the recipient’s motives do not align with the donor’s.

The military coup of February 2021 confronted donors with new dilemmas as to how best to continue to support the population without indirectly strengthening or even recognizing the military’s actions (Fumagalli Citation2022b). Just like in previous instances of military interventions, some countries and donors, controversially, sought to remain engaged, while others withdrew. Perhaps the pendulum will swing again from development to humanitarian aid, as it has before (Décobert Citation2020; Jung Citation2020).

To be clear, this study has a number of limitations. Geocoding aid interventions still confront researchers with several problems of geographic attribution and measurement errors. In this sense, our best guess is that the regional shares we produce are an upper boundary to the actual benefit for these regions. We acknowledge that our efforts are only a first and preliminary attempt and that with better data our picture will become more accurate. Second, we have relied on qualitative information, such as interviews and direct process observations. This revealed our own situated interpretation, and also meant that we depended on the responsiveness and transparency of donor agencies. Third, as discussed at the outset, we are fully aware that using preexisting categories such as “states & divisions”, “center vs. periphery” or “Bamar vs. non-Bamar”, no matter how commonly used, also in the aid sector, is problematic. A fully de-colonial approach will need to not just critique but replace those categories (Sadan Citation2020), so that the production of knowledge in the field of development assistance no longer relies on categories produced and reproduced in pre-colonial, colonial and post-colonial times. Furthermore, it is obvious that there are also many people in Bamar regions in dire need of support and that they are victims of the dominant classes in Myanmar themselves (Campbell and Prasse-Freeman Citation2022).

Given these caveats, the study’s main aim was to start a conversation about the relationship between ODA and regional inequality. We suggest that the Myanmar case holds valuable lessons for other developing countries in Asia and beyond. As we argued above, Myanmar is not necessarily an extreme case in galloping regional inequality and the political polarization this produces. Hence, it will be interesting to see whether and to what extent the findings from the Myanmar case carry over to other countries. Ensuring the “no harm principle” of international aid interventions is very difficult in such regionally polarized cases. From a policy perspective, we increasingly see that better regional targeting of aid within countries also shows beneficial impact on outcomes, such as lower infant mortality and perhaps even on emigration patterns (Kotsadam et al Citation2018b). Thus, there is still a lot to learn about the politics of targeting ODA effectively.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. In this article, we use ODA and (international) aid interchangeably.

2. We use Burma to refer to the country before 1989 and Myanmar for the period after that, as this (formally, the Republic of the Union of Myanmar) is now the official name of the country. We use the term ‘Bamar’ to refer to the majority ethnic group. We use ‘Myanmar’ and ‘Burmese’ interchangeably as adjectives.

3. The transition was contested, its drivers manifold, its evolution uneven and unequal, in many ways reinforcing preexisting inequalities. While change was in many ways real, equally real were the polarization and inequalities that accompanied the process. It was a form of political liberalization and an instance of neoliberal capitalism for some in either the elites or dominant groups, and a multi-faceted form of structural violence for many others. What happened was an example of authoritarian resilience and non-pacted transition from above, with the final destination of that transition being less open-ended than some of the literature was ready to acknowledge.

4. If anything, the most recent Rohingya refugee crisis (Fumagalli Citation2022a) has exacerbated the situation. Parts of Myanmar have become among the least accessible territories for aid agencies (Carr Citation2018; Meehan Citation2015; Meehan and Sadan 2017).

5. We are aware that this is far from the only way for assistance to be provided. Humanitarian aid to Myanmar, for example, has focused on cross-border regions, particularly in the sectors of health and education (Décobert, Citation2020).

6. Administratively Myanmar is divided into 15 units: seven ethnically-defined ‘States’ (Chin, Kachin, Kayah, Kayin, Mon, Rahkine, and Shan), seven Regions (Ayeyarwady, Bago, Magway, Mandalay, Sagaing, Yangon, and Tanintharyi), and one union territory (the capital city, Nay Pyi Taw).

7. With reference to the Kachin experience Sadan (Citation2013) complements the focus on the process of knowledge production in colonial times with a discussion of pre- and post-colonial periods.

8. There is some literature on ODA’s effects on household inequality (Castells-Quintana and Larru 2015; Herzer and Nunnenkamp Citation2012) but often with contradictory findings (Chong et al Citation2009).

9. Of course there are obvious administrative and logistical reasons why it is difficult to roll out aid to the periphery. Fragile states and polities with low state capacity are confronted with challenges in reaching all regions equally even if they wanted to. A pertinent example is provided by intra-state conflicts in which some regions are cut off from aid flows (Duffield Citation2012).

10. Clearly, there are also differences within the Bamar mainland, and the river delta, but these differences are still small compared to the ‘hinterland’.

11. We are grateful to one of the reviewers for focusing our attention on this aspect.

12. The very poor also live in the largely ethnically Bamar areas of the Dry zone and the Delta. We are grateful to one of the reviewers for pointing this out. Also, this is not to say that the borderlands do not experience any form of economic activity. Woods’s and Tharaphi Than' work on ‘ceasefire capitalism’ and borderland politics (Woods, Citation2011; Tharaphi Than, Citation2016), Sarma’s on the resource frontiers (Sarma et al. Citation2022), Aung (Citation2018)'s and Prasse-Freeman’s research on the peripheries as sites of neoliberal capitalism and resource extraction (Mostafanehzad et al. Citation2022) offer important insights and multi-scalar perspectives on capitalism in the borderlands.

13. The data come from the meteorological service of the United States https://ngdc.noaa.gov/eog/index.html (for details see Appendix C).

14. Key bilateral donors include DAC countries such as Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, South Korea, Norway, Sweden, the UK, and the US and non-DAC donors, such as Singapore, India, and Thailand.

15. Multilateral donors include the Asian Development Bank, the European Union, the Global Fund, the United Nations Development Programme, and the World Bank.

16. There are well-known definitional and operational questions concerning what China regards as aid that deserve separate analysis (see for example Dreher, Nunnenkamp and Thiele 2011; Stallings and Kim Citation2017).

17. As shown in https://www.giz.de/en/worldwide/11988.html.

18. Interview, GIZ, Yangon, 17 May, 2019.

19. Interview, GIZ, Yangon, 17 May, 2019.

20. Interviews in Seoul (January 2017) and Yangon (June 2018).

21. Interview with the senior representative of a Western donor agency, Yangon (May 2019).

22. Interviews in Yangon (June 2018) and Seoul (June 2018).

23. See also the map published by JICA (https://libportal.jica.go.jp/library/Data/PlanInOperation-e/SoutheastAsia/030_Myanmar-e.pdf).

24. OSF was not the only international agency involved in higher education reform. There were previous initiatives that helped to prepare the groundwork for launching the new programmes (see Lall Citation2020: 133; IIE Citation2013). Yet OSF’s presence was quite encompassing, and the organization quickly became the government’s main interlocutor in the higher education sector.

References

- Alesina, A., and D. Dollar. 2000. “Who Gives Foreign Aid to Whom and Why?” Journal of Economic Growth 5 (1): 33–63. doi:10.1023/A:1009874203400.

- Alesina, A., S. Michalopoulos, and E. Papioannou. 2016. “Ethnic Inequality.” The Journal of Political Economy 124: 428–488.

- Arase, D, edited by. 2005. Japan’s Foreign Aid: Old Continuities and New Directions. London: Routledge.

- Arulampalam, W., S. Dasgupta, A. Dhillon, and B. Dutta. 2009. “Electoral Goals and Center-State Transfers: A Theoretical Model and Empirical Evidence from India.” Journal of Development Economics 88 (1): 103–119. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2008.01.001.

- Asian Development Bank. 2017. Myanmar 2017–2021. Building the Foundations for Inclusive Growth. Manila: ADB.

- Aung, G. 2018. “Postcolonial Capitalism and the Politics of Dispossession Political Trajectories in Southern Myanmar.” European Journal of East Asian Studies 17 (2): 193–227. doi:10.1163/15700615-01702006.

- Bates, R. 1983. “Modernization, Ethnic Competition, and the Rationality of Politics in Contemporary Africa.” In State versus Ethnic Claims: African Policy Dilemmas, edited by D. Rothchild and V. A. Olorunsola, 152–171. Boulder, CO: Westview.

- Berkowitz, D. 1997. “Regional Income and Secession: Center-Periphery Relations in Emerging Market Economies.” Regional Science and Urban Economics 27 (1): 17–45. doi:10.1016/S0166-0462(96)02143-6.

- Besley, T., and R. Kanbur 1990. The Principles of Targeting. World Bank Working Papers-Poverty March, WPS 385.

- Bissinger, J. 2017. “Foreign Direct Investment and Trade.” In Routledge Handbook of Contemporary Myanmar, edited by A. Simpson, N. Farrelly, and I. Holliday, 212–223. London: Routledge.

- Bluhm, R., A. Dreher, A. Fuchs, B. Parks, A. Strange, and M. Tierney 2018. Connective Financing: Chinese Infrastructure Projects and the Diffusion of Economic Activity in Developing Countries. Aiddata Working Paper Series 64.

- Bodenstein, T., and A. Kemmerling. 2012. “Ripples in a Rising Tide: Why Some EU Regions Receive More Structural Funds Than Others Do.” European Integration Online Papers 16. http://www.people.fas.harvard.edu/ ces/publications/docs/pdfs/CES_157.pdf.

- Bodenstein, Thilo, and Achim Kemmerling. 2015. “A Paradox of Redistribution in International Aid? The Determinants of Poverty-Oriented Development Assistance.” World Development 76 (Supplement C): 359–369. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.08.001.

- Briggs, R.C. 2017. “Does Aid Target the Poorest?” International Organization 71: 187–206.

- Briggs, R.C. 2018. “Poor Targeting: A Gridded Spatial Analysis of the Degree to Which Aid Reaches the Poor in Africa.” World Development 103: 133–148. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.10.020.

- Brooten, L., and R. Metro. 2014. “Thinking About Ethics in Burma Research.” The Journal of Burma Studies 18: 1–22.

- Bueno de Mesquita, B., and A. Smith. 2009. “A Political Economy of Aid.” International Organization 63: 309–340.

- Calabrese, L., and Y. Cao. 2021. “Managing the Belt and Road: Agency and Development in Cambodia and Myanmar.” World Development 141: 105297. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105297.

- Callahan, M.P. 2003. Making Enemies: War and State Building in Burma. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Campbell, S., and E. Prasse-Freeman. 2022. “Revisiting the Wages of Burman-Ness: Contradictions of Privilege in Myanmar.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 52 (2): 175–199. doi:10.1080/00472336.2021.1962390.

- Candier, A. 2019. “Mapping Ethnicity in Nineteen-Century Burma: When ‘Categories of People’ (Lumyo) Became ‘Nations’.” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 50: 347–364.

- Carr, Th. 2018. Supporting the Transition. Understanding Aid to Myanmar Since 2011. Asia Foundation, February.

- Cederman, L-E., N.B. Weidmann, and K.S. Gleditsch. 2011. “Horizontal Inequalities and Ethnonationalist Civil War: A Global Comparison.” The American Political Science Review 105 (3): 478–495. doi:10.1017/S0003055411000207.

- Charney, M.W. 2009. A History of Modern Burma. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Charney, M.W. 2021a. “Decolonizing History in ‘Myanmar’: Bringing Rohingya Back into Their Own History.” Independent Journal of Burmese Scholarship 1: 54–72.

- Charney, M.W. 2021b. “How Racist is Your Engagement with Burma Studies?” FORSEA Forces of Renewal Southeast Asia, 10 June, available at https://forsea.co/how-racist-is-your-engagement-with-burma-studies/

- Chattopadhyay, S. 2013. “Getting Personal While Narrating ‘The Field’: A Researcher’s Journey to the Villages of the Narmada Valley.” Gender, Place and Culture 20: 137–159.

- Chong, A., M. Gradstein, and C. Calderon. 2009. “Can Foreign Aid Reduce Income Inequality and Poverty?” Public Choice 140 (1–2): 59–84. doi:10.1007/s11127-009-9412-4.

- Chu May Paing and Than Toe Aung. 2021. ”Talking Back to White ‘Burma Experts’.” Agitate! August 14.

- David, R., and I. Holliday. 2018. Liberalism and Democracy in Myanmar. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- D’Costa, A.P., edited by. 2015. After-Development Dynamics: South Korea’s Contemporary Engagement with Asia. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Décobert, A. 2014. “Sitting on the Fence? Politics and Ethics of Research into Cross-Border Aid on the Thailand-Myanmar Border.” The Journal of Burma Studies 18: 33–58.

- Décobert, A. 2020. “‘The Struggle Isn’t Over: Shifting Aid Paradigm and Redefining ‘Development’ in Eastern Myanmar.” World Development 127: 104768.

- Décobert, A. 2021. “Health as a Bridge to Peace in Myanmar’s Kayin State: ‘Working Encounters’ for Community Development.” Third World Quarterly 42 (2): 402–420. doi:10.1080/01436597.2020.1829970.

- Décobert, A., and T. Wells. 2020. “Interpretive Complexity and Crisis: The History of International Aid to Myanmar.” European Journal of Development Research 32: 294–315.

- De la Fuente, A., X. Vives, J J. Dolado, and R. Faini. 1995. “Infrastructure and Education as Instruments of Regional Policy: Evidence from Spain.” Economic Policy 10: 13–51. doi:10.2307/1344537.

- Department for International Development (UK) (DfID). 2018 July. Burma. Country Profile (London).

- Dreher, A., P. Nunnekamp, and R. Thiele. 2011. “Are ‘New’ Donors Different? Comparing the Allocation of Bilateral Aid Between nonDac and DAC Donor Countries.” World Development 39: 1950–1968.

- Duffield, M. 2012. “Challenging Environments: Danger, Resilience and the Aid Industry.” Security Dialogue 43: 475–492.

- England, K. V. L. 1994. “Getting Personal: Reflexivity, Positionality, and Feminist Research.” Professional Geographer 46: 80–89.

- Esson, J., and K. Wang. 2018. “Reforming a University During Political Transformation: A Case Study of Yangon University in Myanmar.” Studies in Higher Education 43 (7): 1184–1195. doi:10.1080/03075079.2016.1239250.

- Farrar, L. 2013. “Myanmar’s Educators Reach Out to the World.” New York Times 5 May.

- Fumagalli, M. 2017. ”The Making of a Global Economic Player? An Appraisal of South Korea’s Role in Myanmar.” Academic Papers on Korea 11 (1): 1–8. ( Washington: Korea Economic Institute of America).

- Fumagalli, M. 2022a. “Myanmar’s Muslim Communities Unbound: The Rohingya and Beyond.” In The Rohingya Crisis: Human Rights Issues, Policy Concerns and Burden Sharing, edited by N. Uddin, 228–254. New Delhi: Sage.

- Fumagalli, M. 2022b. The Next Swing of the Pendulum? Cross-Border Aid and Shifting Aid Paradigms in Post-Coup Myanmar. Florence: European University Institute Robert Schuman Centre Policy Papers no. 08.

- Fumagalli, M. 2023. ”Entry, Access, Bans and Returns: Reflections on Positionality in Field Research in Central Asia.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Social Fieldwork, edited by N. Uddin and A. Paul Cham: Springer.

- Fumagalli, M., and M. Rymarenko. 2022. “Krym. Rossiya … Navsegda? Critical Junctures, Critical Antecedents and the Paths Not Taken in the Making of Crimea’s Annexation.” Nationalities Papers, doi:10.1017/nps.2021.75

- Government of Myanmar 2016. Economic policy of the Union of Myanmar. Nay Pyi Taw, August. Available at: https://themimu.info/sites/themimu.info/files/documents/Statement_Economic_Policy_Aug2016.pdf (accessed 19 February, 2020).

- Hardaker, S. 2020. “‘Embedded Enclaves? Implications for Development of Special Economic Zones in Myanmar’.” European Journal of Development Research 32: 404–430.

- Harvey, G. E. 2000. History of Burma: From the Earliest Times to 10 March, 1824: The Beginning of the English Conquest. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services.

- Hedström, J. 2019. “Confusion, Seduction, Failure: Emotions and Reflexive Knowledge in Conflict Settings.” International Studies Review 21: 662–677.

- Hedström, J., and E. Olivius, edited by. 2022. Waves of Upheaval in Myanmar. Gendered Transformations and Political Transitions. Copenhagen: NIAS Press.

- Henderson, J.V., A. Storeygard, and D.N. Weil. 2012. “Measuring Economic Growth from Outer Space.” The American Economic Review 102 (2): 994–1028. doi:10.1257/aer.102.2.994.

- Heo, U., and T. Roehrig. 2014. South Korea’s Rise. Economic Development, Power, and Foreign Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Herzer, D., and P. Nunnenkamp. 2012. “The Effect of Foreign Aid on Income Inequality: Evidence from Panel Cointegration.” Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 23: 245–255.

- Holliday, I., and Zaw Htet. 2017. “International Assistance.” In Routledge Handbook of Contemporary Myanmar, edited by A. Simpson, N. Farrelly, and I. Holliday, 347–354. London: Routledge.

- Htet, Min Lwin. 2021. ”Federalism at the Forefront of Myanmar’s Revolution.” Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia 31 available at https://kyotoreview.org/issue-31/federalism-at-the-forefront-of-myanmars-revolution/

- Ikeya, C. 2020. “Belonging Across Religion, Race, and Nation in Burma-Myanmar.” In The Palgrave International Handbook of Mixed Racial and Ethnic Classification, edited by Z.L. Rocha and P.J. Aspinall, 757–778. Cham: Springer.

- Institute of International Education (IIE). 2013. Investing in the Future: Rebuilding Higher Education in Myanmar. New York: IIE.

- International Crisis Group (ICG) 2002. The Politics of Humanitarian Aid. Asia Report 32, Bangkok/Brussels, April 2.

- International Crisis Group (ICG) 2004. Myanmar: Aid to the Border Areas. Asia Report 82, Yangon/Brussels, September 9.

- Jones, L. 2014. “Explaining Myanmar’s Regime Transition: The Periphery is Central.” Democratization 21: 780–802.

- Jung, W. 2020. “Two Models of Community-Centred Development in Myanmar.” World Development 136: 105081.

- Kappler, S. 2021. “Privilege.” In The Companion to Peace and Conflict Fieldwork, edited by Roger Mac Ginty, Roddy Brett, and Birte Vogel, 421–432. Cham: Springer.

- Kiik, L. 2016. “Nationalism and Anti-Ethno-Politics: Why ‘Chinese Development’ Failed at Myanmar’s Myitsone Dam.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 57 (3): 374–402. doi:10.1080/15387216.2016.1198265.

- Kim, H-S. 2018. “The Political Drivers of South Korea’s Official Development Assistance to Myanmar.” Contemporary Southeast Asia 40: 475–502.

- Knott, E. 2019. “Beyond the Field: Ethics After Fieldwork in Politically Dynamic Contexts.” Perspectives on Politics 17 (1): 140–153. doi:10.1017/S1537592718002116.

- Koch, N. 2013. “Introduction - Field Methods in ‘Closed Contexts’: Undertaking Research in Authoritarian States and Places.” Area 45 (4): 390–395. doi:10.1111/area.12044.

- Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA). 2017. The Republic of Korea’s Country Partnership Strategy for the Republic of the Union of Myanmar. Seoul: KOICA.

- Kotsadam, A., G. Østby, S.A. Rustad, A.F. Tollefsen, and H. Urdal. 2018b. “Development Aid and Infant Mortality. Micro-Level Evidence from Nigeria.” World Development 105: 59–69. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.12.022.

- Kramer, T. 2021. “‘Neither War nor Peace’: Failed Ceasefires and Dispossession in Myanmar’s Ethnic Borderlands.” Journal of Peasant Studies 48 (3): 476–496. doi:10.1080/03066150.2020.1834386.

- Lall, M. 2020. Myanmar’s Education Reforms: A Pathway to Social Justice?. London: UCL Press.

- Loong, S. 2021. Centre-Periphery Relations in Myanmar: Leverage and Solidarity After the 1 February Coup. ISEAS: Singapore.

- Malejacq, R., and D. Mukhopadhyay. 2016. “The ‘Tribal Politics’ of Field Research: A Reflection on Power and Partiality in 21st-Century Warzones.” Perspectives on Politics 14 (4): 1011–1028. doi:10.1017/S1537592716002899.

- Manuel, M., D. Coppard, A. Dodd, H. Desai, R. Watts, Z. Christensen, and S. Manea 2019 Subnational Investment in Human Capital, ODI and DI Report. https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/resource-documents/12663.pdf (accessed 19 January, 2021)

- Maung, Zarni 2021. “Transnational Activism Vs White Saviourism in Myanmar Affairs.” Zarni’s Blog, 4 September, available at https://www.maungzarni.net/en/news/transnational-activism-vs-white-saviourism-myanmar-affairs

- McCorkel, Jill A., and K. Myers. 2003. “What Difference Does Difference Make? Position and Privilege in the Field.” Qualitative Sociology 26: 199–231.

- Meehan, P. 2015. “Fortifying or Fragmenting the State? The Political Economy of Opium/Heroin Trade in Shan State, Myanmar, 1988-2013.” Critical Asian Studies 47 (2): 253–282.

- Meehan, P., and M Sadan. 2018. “Borderlands.” In Routledge Handbook of Contemporary Myanmar, edited by A. Simpson, N. Farrelly, and I. Holliday, 83–91. London: Routledge.

- Mekasha, T.J., and F. Tarp. 2013. “Aid and Growth: What Meta-Analysis Reveals.” The Journal of Development Studies 49: 564–583.

- Metro, R. 2019. ”We Need to Talk About the Consultancy Industry in Educational Development.” Comparative and International Education Society Perspectives Summer :39–40.

- Mosse, D. 2006. “Anti-Social Anthropology? Objectivity, Objection and the Ethnography of Public Policy and Professional Communities.” The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 12: 935–956.

- Mostafanezhad, M., T. Sebro, E. Prasse-Freeman, and R. Norum. 2022. “Surplus Precaritization: Supply Chain Capitalism and the Geoeconomics of Hope in Myanmar’s Borderlands.” Political Geography 95: 102561.

- Neumayer, E. 2003. “The Determinants of Aid Allocation by Regional Multilateral Development Banks and United Nations Agencies.” International Studies Quarterly 47: 101–122.

- Nilsen, M. 2020. “Perceptions of Rights and the Politics of Humanitarian Aid in Myanmar.” European Journal of Development Research 32: 338–358.

- Nunnenkamp, P., H. Öhler, and M. S. Andrés. 2017. “Need, Merit and Politics in Multilateral Aid Allocation: A District‐level Analysis of World Bank Projects in India.” Review of Development Economics 21: 126–156.

- Öhler, H., and P. Nunnenkamp. 2014. “Needs‐based Targeting or Favoritism? The Regional Allocation of Multilateral Aid Within Recipient Countries.” Kyklos 67 (3): 420–446. doi:10.1111/kykl.12061.

- Østby, G., R. Nordas, and J.K. Rød. 2009. “Regional Inequalities and Civil Conflict in Sub-Saharan Africa.” International Studies Quarterly 53 (2): 301–324. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2478.2009.00535.x.

- Parks, Th., N. Colletta, and B. Oppenheim. 2013. The Contested Corners of Asia: Subnational Conflict and International Development Assistance. San Francisco, CA: Asia Foundation.

- Phyo, Win Latt. 2011. “Postcolonial and Subaltern Studies in Asian Context and Its Prospects.” Scholar Research and Development Journal 3: 229–244.

- Prasse-Freeman, E., and Phyo Win Latt. 2017. “Class and Inequality.” In Routledge Handbook of Contemporary Myanmar, edited by A. Simpson, N. Farrelly, and I. Holliday, 404–416. London: Routledge.

- Reiffel, L., and J.W. Fox. 2013. Too Much, Too Soon? The Dilemma of Foreign Aid to Myanmar/Burma. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

- Reilly, J. 2013. “China and Japan in Myanmar: Aid, Natural Resources and Influence.” Asian Studies Review 37 (2): 141–157. doi:10.1080/10357823.2013.767310.

- Rippa, A. 2020. “Mapping the Margins of China’s Global Ambitions: Economic Corridors, Silk Roads, and the End of Proximity in the Borderlands.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 61 (1): 55–76. doi:10.1080/15387216.2020.1717363.

- Sadan, M. 2013. Being and becoming Kachin: Histories beyond the state in the borderworlds of Burma. British Academy scholarship online.

- Sadan, M. 2014. ”Reflections on Building an Inclusive Higher Education System in Myanmar.” available at. British Academy Review 24: 68–71. https://eprints.soas.ac.uk/18900/1/Building%20an%20Inclusive%20Higher%20Education%20System%20in%20Myanmar.pdf

- Sadan, M. 2020. “Why Decolonising Area Studies is Not Enough: A Case Study of the Complex Legacies of Colonial Knowledge-Making in the Indo-Myanmar Borderlands.” New Area Studies 1 (1): 180–220. doi:http://doi.org/10.37975/NAS.34.

- Sarma, J., H.O. Faxon, and K.B. Roberts. 2022. “Remaking and Living with Resource Frontiers: Insights from Myanmar and Beyond.” Geopolitics 1–22. doi:10.1080/14650045.2022.2041220.

- Scott, J.C. 2009. The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Shimomura, Y., J. Page, and H. Kato. 2016. Japan’s Development Assistance: Foreign Aid and the Post-2015 Agenda. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- South, A. 2008. Ethnic Politics in Burma. London: Routledge.

- Stallings, B.and E.M. Kim. 2017. “Japan, Korea and China: Styles of ODA in East Asia.” In Promoting Development: The Political Economy of East Asian Aid, edited by B. Stallings and E. M. Kim, 120–134. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Steinberg, D.I. 1991. “Democracy, Power, and the Economy in Myanmar: Donor Dilemmas.” Asian Survey 31: 729–742.

- Steinberg, D.I., and H. W. Fan, edited by. 2012. Modern China-Myanmar Relations: Dilemmas of Mutual Dependence. Copenhagen: NIAS Press.

- Stokke, K., and Soe Myint Aung. 2020. “The Transition to Democracy or Hybrid Regime? The Dynamics and Outcomes of Democratization in Myanmar.” European Journal of Development Research 32: 274–293.

- Strefford, P. 2016. “Japan’s Bounty in Myanmar.” Asian Survey 56: 488–511.