ABSTRACT

When the popularity of the populist radical right increases, questions arise. Where are these parties successful? Does the geographic distribution of their support change along with changes in their primary issues? This article analyzes spatial aspects in the support of populist radical right parties in Slovakia and Czechia and their change over time. The spatial distribution was examined using spatial autocorrelation.The results showed that these parties have strong support in “left-behind” regions and peripheral rural regions and weak support in the surroundings of largest cities. The distribution of support for parties also changed more significantly when the parties changed the presented main issues. In Slovakia there was visible spatial competition between the traditional populist radical right party, the Slovak National Party (SNS), and newer and adaptable party, the People’s Party Our Slovakia (ĽSNS). ĽSNS succeeded in areas with traditionally strong support for SNS thanks to changes in its main electoral themes. In Czechia, the distribution of support between Dawn and Freedom and Direct Democracy (SPD) has changed. Dawn had a support distribution similar to the populist party Public Affairs, which shared ideas of direct democracy. SPD’s support distribution was closer to areas traditionally supporting the populist radical right.

Introduction

The electoral success of the populist radical right (PRR) has increased in Europe over the last decade. Its achievements include advancement to the second round of Marine Le Pen in the French presidential election, third place for Alternative für Deutschland in the German federal election, and second place for Partij voor de Vrijheid in the Dutch parliamentary elections. All these successes took place in 2017. PRR parties have also been successful in the European Parliament election despite their criticism of this institution. The PRR has also found success in Slovakia and Czechia. Its electoral support there has increased in the last ten years, and new PRR parties have been successful in parliamentary elections.

Several questions arise as regards the growing popularity of the PRR in Europe: In which areas does it have strong or weak electoral support? Do these regions have anything in common? Has the distribution of electoral support for the PRR changed over time, or has it remained stable over the long term?

This article offers a spatial analysis of support for PRR parties in Slovakia and Czechia. The countries have been chosen because they have historical and political similarities. Situated in Central and Eastern Europe, they are both post-socialist countries which together had, until 1993, formed one state. Still, the long-term popularity of the populist radical right differs in these countries. Thus, it is possible to analyze whether the spatial distribution of the PRR differs or whether, despite the differences, there is a similar trend of support for the PRR in the post-socialist countries of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE).

The article contributes to the geographic study of the PRR in several ways. First, I show which areas have strong or weak support for this type of party family. I further demonstrate how the global, local, and historical specificities or regions are important to the spatial distribution of the PRR. I also show how the distribution of support has changed over time, and how that change is connected to a shift in these parties’ ideological focus. I further reveal whether PRR parties are competing geographically. And finally, this study is unique in that it analyses the electoral results of support for the PRR at the municipal level.

In the following section, I will present the evolution and research of the PRR. Then I will analyze geographical literature, and its understanding of the PRR. In the next section, I will present a brief history of the PRR in Slovakia and Czechia. The methodological section will describe the spatial techniques used in the ensuing section. The paper then concludes with a summary of the ways in which the PRR is spatiotemporally stable in both countries.

Evolution and research of the populist radical right

Since the end of World War II, political scientists have identified three waves of support for PRR parties in Western Europe (Mudde Citation1996). The first wave is the rise of neo-fascist and neo-Nazi parties in Germany and Italy shortly after the war. Scientists describe the second wave as the spread of radical right parties in the 1950s and 1970s in France and the Scandinavian countries, which protested high taxes. The third wave of radical right party expansion occurred in the 1980s with the dawn of radical and markedly xenophobic parties (Mudde Citation1996). However, the populist radical right parties in the third wave differ from their predecessors. Several authors therefore divide PRR parties into an old and new radical right (Mikuš and Gurňák Citation2019).

According to Rydgren (Citation2007), the new PRR is less aggressive and strives for ethnic purity within the state rather than global neo-fascist or neo-Nazi racial purity. Therefore, these parties recognize other ethnic groups, but only within their national borders. The new PRR also looks more closely at historical events.

The popularity of the PRR grew between 2007 and 2009 during the economic crisis. The resolution of the migration crisis in 2015 and 2016, dissatisfaction with the functioning of the European Union (Vasilopoulou Citation2018), and the increase in Islamophobia (Kallis Citation2018) related to terrorist attacks in Europe also contributed to this rise in popularity. Bornschier (Citation2018) points out that global processes like the globalization of trade or the influence of multinational companies on the functioning of the state economy also help to increase PRR popularity.

Unlike in Western Europe, where authors have analyzed the PRR since the 1980s, interest in the populist radical right in CEE did not begin until the turn of the twenty-first century. The first works dealing with this issue include papers by Mudde (Citation2000, Citation2005) and Minkenberg (Citation2002). Mudde (Citation2005) describes the populist radical right in CEE as racist and extremist. According to him, the study of subcultures and the issues of are essential for understanding the PRR in this area.

Bustiková (Citation2018) states that three specifics characterize the populist radical right in CEE as compared to that of Western Europe. The first is that, from an economic point of view, the parties of the PRR have more ideas characteristic of left-wing parties than parties on the right. The second specificity is that they combine democratization with granting rights to minorities and thus their favoring over that of the majority society. Thirdly, there has been a radicalization of mainstream political parties, which then coexist with PRR parties.

Authors from the studied countries have also dealt with the issue of the populist radical right in CEE, analyzing the PRR in a specific state (Mareš Citation2003; Sum Citation2010; Mikuš and Gurňák Citation2012; Gregor Citation2015; Kasprowicz Citation2015; Krekó and Mayer Citation2015; Kluknavská and Smolík Citation2016) or across several countries (Kupka, Laryš, and Smolík Citation2009; Mikuš and Gurňák Citation2016, Citation2019). Their research shows that the populist radical parties initially strongly emphasized the Roma issue and the poor economic situation in selected regions. In recent years, however, the migration crisis, fear of Islam, protection of Christian values, and Euroscepticism have been popular themes for these parties. This brings them closer to PRR parties in Western Europe (Polyakova Citation2015; Pytlas Citation2018).

But what criteria must a party fulfill to be called a populist radical right party? According to Mudde (Citation2007), these include nativism, authoritarianism, and populism. Nativism is a combination of nationalism and xenophobia. Therefore, nativist political parties are characterized on the one hand by anti-immigrant attitudes; xenophobia toward national, religious, or other minorities; and warnings of external threats to the state, and on the other hand by highlighting the nation and economic protectionism.

As regards the second criterion of authoritarianism, Mudde (Citation2007) does not necessarily consider only the anti-democratic attitudes of the parties to be a sign of this. He also takes authoritarianism to be faith in a strictly organized society in which violations of this arrangement are strictly punished. Thus, the parties emphasize the issues of crime, security, severe penalties for criminals, and the establishment of order in the state.

The third criterion is populism. According to Mudde (Citation2007), populist parties are characterized by dividing society into people and a corrupt elite as well as strongly supporting the people’s will, for example, by trying to push for referendums. Populist parties also glorify the people as a source of morality and virtue, and this glorification contrasts sharply with criticism of the elite (Stanley Citation2011).

Electoral geography and the populist radical right

The topic of the populist radical right is not as common in geographical works as in political science and sociological works. However, as the popularity of these parties increases, so does interest among geographers. These works are important because they point to the importance of spatial aspects in understanding the popularity of PRR parties.

Geography has long been working with how voters are influenced in their political choices by the environment in which they live or work (Taylor Citation1985). This includes interaction with people around them and the various specifics of a region. These specifics can be divided between global specifics, local specifics, and historical specifics (Giordano Citation1999, Citation2001; Flint Citation2001; Johnston and Pattie Citation2006; Mikešová Citation2019).

The global specifics of a region can be those that cause a region to have some economic or cultural characteristics associated with the impact of globalization. In support of the PRR in Europe, the most important cultural factor of globalization is people’s fear of migrants and an increase in crime caused by them (Shuermans and De Maesschalck Citation2010). Research shows that this fear produces an increase in the popularity of the PRR, especially in rural areas with little contact with migrants (van Gent, Jansen, and Smits Citation2014; Steinmayr Citation2016). The global economic factor is the inability of these regions to adapt to new global economic trends and their greater difficulty in managing global economic crises. Such regions are commonly referred to as “left-behind” regions (Furlong Citation2019; Greve, Fritsch, and Wyrwich Citation2021). Essletzbichler, Disslbacher, and Moser (Citation2018) claim these regions, which include old industrial regions, regions with higher unemployment, and regions with labor markets affected by the economic crisis, have a greater tendency to support PRR parties.

Several local specifics also influence local election behavior. One important aspect, as per Giordano (Citation1999, Citation2000) is a region’s location within the state. If a region’s people feel overlooked by the central government, it increases their willingness to vote for parties critical of the government. For this reason, PRR parties have more significant support in the peripheral areas of the state (Giordano Citation2000; Mikuš and Gurňák Citation2019). Another local specific is natural conditions. Bernard and Kostelecký (Citation2014) report that issues such as floods, clean air, and energy self-sufficiency can make the inhabitants of these regions who have a problem with these natural conditions more likely to make political choices based on these topics. Forchtner (Citation2019) points out that PRR parties often highlight the traditional landscape, the countryside, and nature conservation when criticizing or denying climate change (global warming, Green Deal), and this may also increase voter interest in the PRR in rural areas. Local community problems and the local activities of political parties is yet a third local specificity (Bernard and Kostelecký Citation2014). If voters in the region have a problem with the local Roma community, they are more likely to vote for PRR parties that draw attention to this type of problem (Maškarinec and Bláha Citation2014; Mikuš and Gurňák Citation2019). Another local specificity is the “friends and neighbors” effect. PRR candidates receive more votes in their area of residence or political activity, and this support decreases as the distance from this area increases (Taylor Citation1985). This effect is more evident in rural areas than in larger cities (Gimpel et al. Citation2008). The last local specificity is the dissatisfaction of inhabitants with their regional development. Suppose the population sees socioeconomic development declining in their region and, at the same time, according to inhabitants, the regional development policy of the central government and the European Union in their region is not working. Thus, voters are more likely to vote for parties that criticize the functioning of the state and are Euroskeptic (Buček and Plešivčák Citation2017). Relatedly, research by Schulte-Cloos and Leininger (Citation2022) points to the important role of localized political disaffection in explaining the success of the PRR but leaves open the question as to the sources of this local disaffection.

The last group of specifics of region that influence electoral behavior is historical specifics. Giordano (Citation1999) notes that regions with similar global and local specificities, but different historical development also have different electoral results. Greve, Fritsch, and Wyrwich (Citation2021) refer to this phenomenon as place-based collective memory. It describes the fact that voters are also influenced by the position of their region in the past when choosing a party in the elections. So, if the region has been affected by socioeconomic problems that are no longer relevant, voters are still more likely to vote for PRR parties that point to these problems (Greve, Fritsch, and Wyrwich Citation2021; Kevický Citation2021). Šimon (Citation2015) works with the concept of “phantom borders” in connection with the historical specifics of the region. The idea is based on the fact that in elections, historical borders that no longer exist are visible on electoral maps.

The global, local, and historical specificities of regions influence where support for the PRR is stronger, but the populist radical right can change ideologically and thematically over time. Thus, their regional distribution can change as well. A typical example is Germany’s Alternative für Deutschland. This economically and culturally conservative and decidedly Euroskeptic party changed into a widely successful PRR party (Arzheimer and Berning Citation2019). In 2013, the party was successful across Germany. Now, however, the party is much more successful in eastern Germany than in the west of the country (Weisskircher Citation2020) and has been remarkably successful in regions that experienced long-term economic decline (Greve, Fritsch, and Wyrwich Citation2021). Mikuš and Gurňák (Citation2016) also show that when Slovak (People’s Party Our Slovakia) and Hungarian (Jobbik) PRR parties changed their electoral program, the spatial distribution of their popularity changed with it.

Populist radical right in Slovakia and Czechia

The oldest and longest running PRR party in Slovakia is the Slovak National Party (SNS). From its founding in 1990, SNS was one of the few political entities that demanded Slovakia’s independence from Czechoslovakia (Žatkuliak Citation2004). The party became much more radicalized in 1994 when Ján Slota became the party’s chair. He promoted patriotic, nationalistic, and chauvinistic views and was particularly critical of the Hungarian minority in Slovakia (see Kupka, Laryš, and Smolík Citation2009). A split in the party occurred in 1999 when Anna Malíková was elected as the party’s new chair. This caused Slota to leave the party and found the True Slovak National Party (PSNS). However, the failure of SNS and PSNS in the 2002 parliamentary elections led to the parties’ reunification, with Slota once again as leader. He led the party until 2012 when SNS failed to enter parliament (see appendix A). He was replaced as party leader by Andrej Danko. The party also abandoned its anti-Hungarian rhetoric and began to focus more on anti-Roma issues, adopted an anti-migrant stance, positioned itself as a defender of the traditional family, and displayed antagonistic attitudes toward NATO (Gurňák and Mikuš Citation2012; Mikuš and Gurňák Citation2019). Thanks to the change in party chair and rhetoric, SNS managed to return to the Slovak parliament in 2016 but was unsuccessful again in the 2020 elections. Interestingly, SNS is the only PRR party in either Czechia or Slovakia that has been part of the government. The party has long-term support in the north of the country and, by contrast, has weak electoral support in the south, a region with a higher share of ethnic Hungarians.

The People’s Party Our Slovakia (ĽSNS), another PRR party, also managed to enter the Slovak parliament. In 2010, Marian Kotleba became the party’s chairman, after which the party began to take a strongly chauvinist orientation. In its early days, the party glorified the wartime Slovak state and made racist statements about the Roma. Party members even went to regions with higher levels of Roma crime, thus gaining the sympathy of the local population. This was also reflected in the party’s electoral support: in the 2010 and 2012 elections, ĽSNS had the strongest support in regions with a higher proportion of Roma residents (Mikuš and Gurňák Citation2019). The party’s first success was the victory of Marian Kotleba for the president of the Banská Bystrica region in the 2013 regional elections. However, ĽSNS did not win a single seat in the regional assembly, and Kotleba thus remained politically completely isolated in the regional council. The party also changed the issues it was highlighting. ĽSNS began to criticize the government’s regional development policy, the functioning of European Union subsidies, and the functioning of the globalized economy. Thanks to this, the party was also able to gain votes in regions that were suffering the consequences of the economic crisis and dysfunctional regional development (Buček and Plešivčák Citation2017). Thanks to its anti-migrant attitudes, criticism of Islam, and accent on the importance of traditional families and values, ĽSNS succeeded in the 2016 and 2020 parliamentary elections. And with these themes, the party managed to succeed mainly in peripheral rural areas and regions with higher unemployment (Mikuš and Gurňák Citation2019). However, in the autumn of 2020, the party’s leader Marian Kotleba was convicted of extremism, and, the following year, six members of the Slovak parliament left the party. In 2022, Marian Kotleba lost his parliamentary mandate because he was given a definitive suspended sentence for promoting and supporting extremism.

The situation in Czechia was different. In the 1990s, the Association for the Republic – Republican Party of Czechoslovakia was a successful PRR party. Its chair was the former Communist censor, Miroslav Sládek. The party was characterized by its strongly anti-Roma rhetoric, opposition to the Czech entry into the European Union and NATO, and demand for the annexation of Carpathian Ruthenia to Czechoslovakia, and respectively to Czechia. Economically, the party opposed the privatization of state companies and supported investment in rural development and housing construction (Mareš Citation2003). However, after the party failed in the 1998 elections, no PRR party entered the parliament again until 2013.

The most notable PRR party in this second period was the Workers’ Party, which continued the policies of the Republican Party because its chair was former Republican Party member Tomáš Vandas. Under his leadership, the party proclaimed that it was against corruption and political elites, demanded leaving the European Union and NATO, fitted itself as a defender of the traditional family, and had strong anti-Roma and anti-migrant rhetoric (Mareš Citation2012). Because of its extremist views, the party was banned, but Tomáš Vandas founded its successor, the Workers’ Party of Social Justice (DSSS).

Interestingly, the composition of electoral support for the populist radical Right remained stable throughout the period, until 2013. The PRR had high support in the northwestern part of Czechia, where there are regions with a higher Roma population, a lower proportion of believers, and a lower level of education. PRR parties had weak support in Prague and around the capital (Mareš Citation2012; Pink and Voda Citation2012).

In the 2010 election, for the first time in Czech political history, a successful centrist populist party, Public Affairs (VV), entered parliament and the government. The party was registered in 2002, but VV became better known in 2009. At that time, the party announced that its electoral leader was former writer and investigative journalist, Radek John. However, the de facto leader of VV was businessperson Vít Bárta. The party criticized political corruption in its program and emphasized various elements of direct democracy (Havlík and Hloušek Citation2014). VV’s success in the 2010 parliamentary elections was mainly in the eastern part of the country (Havlík and Voda Citation2016; Maškarinec Citation2017). In 2011, Bárta, as minister of transport, was accused of bribery by his party colleagues, and he resigned. A year later, Bárta was convicted of corruption, after which some of VV’s MPs left the party.

Several VV representatives, like Bárta, ran in the 2013 elections as candidates for Dawn of Direct Democracy. The party chair was Tomio Okamura, a Czech politician and entrepreneur of Czech, Japanese and Korean ethnicity. This new Czech PRR party was successful in the elections and entered parliament. Dawn, similar to VV, sought to promote the principles of direct democracy and criticized corruption in politics. Dawn also criticized the functioning of the government and the European Union. The party’s success was mainly in Moravia and eastern Bohemia (Havlík and Voda Citation2016; Maškarinec Citation2017). Later, after disagreements with other party members, party chair Tomio Okamura would leave the party to establish a new political party, Freedom and Direct Democracy (SPD). SPD has a similar program to Dawn but is more concerned with immigration and Islamization. These political attitudes were also reflected in a change in the party’s popularity, as it gained more votes in old industrial regions and peripheral rural areas in the northwestern part of Bohemia and northern Moravia (Maškarinec Citation2019).

Based on the development of the Slovak and Czech PRR and the analysis of previous results, I have created the following hypotheses:

H1:

The populist radical right has strong support in “left-behind,” peripheral rural regions and regions experiencing long-term economic decline.

H2:

When the thematic focus of the PRR changes, the distribution of its electoral support will also change.

The first hypothesis shows that global, local, and historical specificities of region are important to the distribution of the PRR. The second reflects spatial changes related to changes in PRR party programs.

Data and methods

I have used several spatial techniques to control for the influence of spatial effects and analyze the dynamics of Slovak and Czech PRR parties. First, my exploration of the spatial structure of electoral support began with the formal detection of spatial autocorrelation using Moran’s I statistic (Cliff and Ord Citation1981). However, Moran’s I is an overall measure of linear association, whose single value is valid for the entire study area. Since this study aims to identify potentially different patterns of voting behavior within larger units and their transformation between elections, a local indicator of spatial association (LISA) was used to obtain more detailed insight into how electoral support was clustered throughout the Slovak and Czech territories.

As I wanted to compare differences across several elections and PRR parties, I used univariate LISA indicators, which show clustering of support for one party in one election, and bivariate LISA indicators, which can compare spatial differences between pairs of elections or between pairs of parties (Anselin Citation1995). The univariate LISA is calculated for each observation. It provides information about the degree and nature of clustering around each observation by determining the contribution each observation makes to the overall global statistic (Shim and Agnew Citation2007). LISA values can identify positive spatial dependence (high values surrounded by similarly high values or low values surrounded by similarly low values) or spatial outliers (high values surrounded by low values or low values surrounded by high values). The bivariate LISA is calculated similarly to the univariate LISA, but a different variable is used for the spatial lag component (Shim and Agnew Citation2007). This allows for comparison of clustering between pairs of elections or between pairs of political parties.

In this paper, I analyzed data on the Slovak National Council elections from 2010 to 2020 and the Czech Chamber of Deputies elections from 2010 to 2021Footnote1. The choice of 2010 as the starting point of analysis was because it was the first time ĽSNS candidates participated in the Slovakian national elections. That year also the first exclusively populist party, Public Affairs, successfully entered the Chamber of Deputies. My primary indicator for political preference was the percentage of votes achieved by the parties at the municipal level. I worked with 2,889 municipalities in Slovakia and 6,258 municipalities in Czechia. I analyzed the distribution of political support for SNS and ĽSNS in Slovakia and Dawn, SPD, VV, and DSSS in Czechia.

Spatial analysis of populist radical right parties in Slovakia and Czechia

Where is the PRR successful?

Although Slovak and Czech PRR parties had slightly different positions in the analyzed period, similar global spatial clustering of electoral support patterns is visible among the countries (appendix B). In both Slovakia and Czechia, the value of the Moran’s I scores slightly increased over time. That suggests that the global spatial clustering of electoral support for these parties has also slightly grown over time. An exception was SNS’s Moran’s I score in 2020, which achieved a significant decrease in electoral support that year. From this, it can be assumed that PRR parties have a higher spatial clustering when they are more established on the political scene and, at the same time, do not significantly lose electoral support. An increase in clustering could be explained by strengthening the regionalization of the party’s support in certain territories.

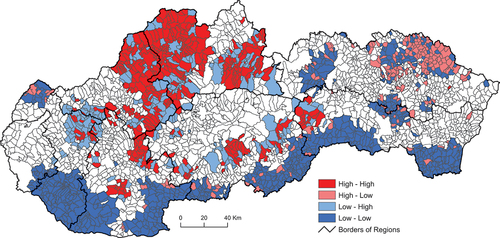

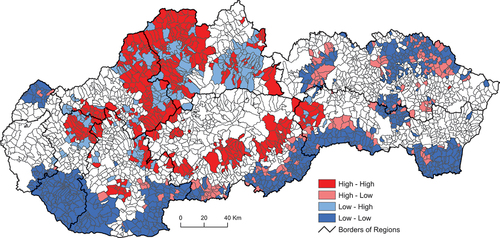

SNS had no major transformation in the spatial patterns of its electoral support between 2010 and 2016. Clusters of strong support for the party were mainly in part of central and western Slovakia (the Žilina, Trenčín, and Banská Bystrica regions) - municipalities with a largely Slovak population. This part of Slovakia is the traditional core of SNS’s popularity, in part because Slota, the party leader, was mayor of Žilina for a long time. Clusters of weak support were concentrated in southern parts of Slovakia, where there is a larger population of ethnic Hungarians; around the two largest Slovak cities, Bratislava and Košice; and in some municipalities of eastern Slovakia. However, the loss of more than five percentage points between the 2016 and 2020 elections brought about change. The clusters of weak support remained concentrated in southern Slovakia and around the two largest Slovak cities; however, clusters of weak support in eastern Slovakia almost disappeared. More importantly, the party suffered a significant drop in a large part of its traditional core constituencies in part of central and western Slovakia. New clusters of strong support were instead created in rural peripheral areas in eastern parts of Slovakia near the borders of Poland and Ukraine, paradoxically, in regions where traditionally there were more successful left-wing parties (Pink and Voda Citation2012).

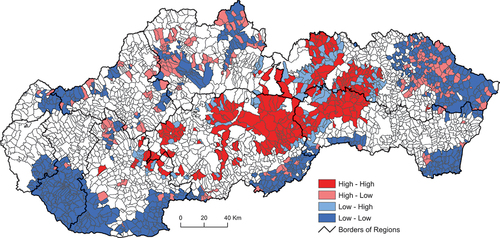

ĽSNS had clusters of strong support in regions of central and eastern Slovakia with a larger Roma minority population in the 2010 and 2012 elections. Clusters of weak support were in the south of Slovakia, in regions with a larger Hungarian minority population; in the traditional core of SNS in the Žilina Region; and in the northeastern parts of Slovakia, where left-wing parties are traditionally rather popular (Pink and Voda Citation2012). The party’s success in the following 2016 elections, when ĽSNS gained more than six percentage points, changed the distribution of the party’s support. The clusters of weak support in southern Slovakia remained. Still, the cluster of weak support in northeastern parts of Slovakia shrank, whereas those in the Žilina region disappeared. On the contrary, new clusters of strong support appeared in Žilina. Other larger clusters of strong support were in Banská Bystrica, where Marian Kotleba was at that time leader of the regional government. Four years later, in the 2020 elections, the changes in electoral support were not as significant. ĽSNS had larger clusters of strong support in Banská Bystrica. Other clusters of strong support were in the western part of east Slovakia and in traditional regions of strong support for SNS in western and central Slovakia. The clusters of weak support remained in southern Slovakia. The cluster of weak support in the northeast parts of Slovakia on the other hand disappeared and a new cluster of weak support emerged in the middle part of eastern Slovakia, from Košice to the borders with Poland.

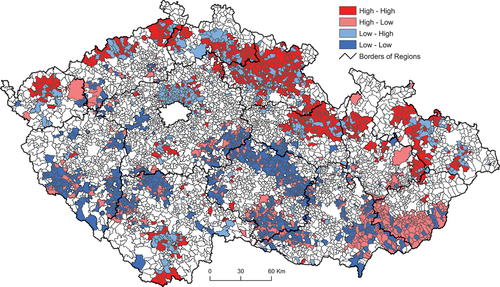

In the 2010 elections, the traditional Czech PRR party, DSSS, had clusters of strong support in the old industrial regions of northern Bohemia with high unemployment and larger Roma minority populations, as well as in some rural peripheral regions in Moravia. Clusters of weak support were found around big cities and regions with a higher proportion of believers. The distribution of support for DSSS in 2010 is thus located in traditional regions with longstanding support for the PRR (Mareš Citation2012; Pink and Voda Citation2012). Meanwhile, the populist VV had clusters of strong support in the east of Czechia in the 2010 elections (Maškarinec Citation2017).

In the 2013 elections, Dawn had clusters of strong support mainly in Moravia and the eastern part of Bohemia and weak support clusters in Prague, its surroundings, and the western part of Czechia. One of the reasons for the higher popularity of Dawn in Moravia was that Tomio Okamura, the leader of Dawn, was, at that time, a senator from Zlín. When Tomio Okamura ran as a candidate with his new political party, SPD, in the 2017 election, there were some spatial changes in the distribution of electoral support. The main clusters of strong support in Moravia remained, but those in eastern Bohemia disappeared. SPD had new clusters of strong support in peripheral rural areas in southern and northern Moravia as well as the old industrial regions in northwest BohemiaFootnote2. The clusters of weak support stayed in similar places. In the 2021 election clusters of strong and weak support for SPD were very similar to the 2017 elections: noticeable differences included a shrinking of the clusters of strong support in south Moravia, new clusters of strong support in the old industrial and mining region near Ostrava in northern Moravia, and clusters of strong support in northwest Bohemia expanded into other peripheral and old industrial regions.

Spatiotemporal (In)stability of populist radical right parties?

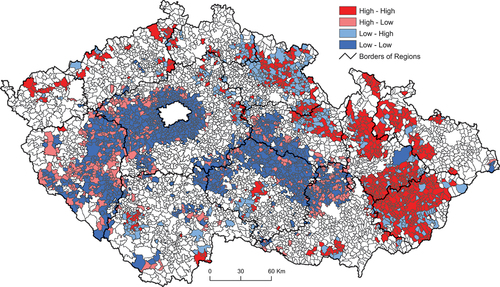

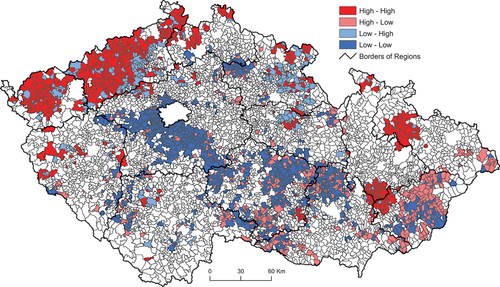

The second hypothesis suggests that when the thematic focus of a PRR party changes, the distribution of its electoral support will also change. My results indicate that spatial support for the PRR in Slovakia has changed over time (). In the 2010 and 2016 elections, electoral support for the traditionally Slovak PRR party, SNS, was in areas characterized by long-term support for the party (Mikuš and Gurňák Citation2019). This was mainly due to its traditional themes, such as protecting the Slovak nation against external threats (typically from Hungary; Mikuš and Gurňák Citation2019). However, the party’s inability to adapt to new issues typical of the PRR in Western Europe and the party’s participation in government, which meant that the party could not criticize the central government and EU policy, led the party to lose much of its electoral support in the 2020 elections. That also led to a change in the distribution of electoral support for SNS when the party lost its traditional regions in central and western Slovakia to ĽSNS. Their electoral support instead moved to peripheral municipalities in northwestern Slovakia ().

Table 1. Bivariate Moran’s I score for analyzed parties in Slovakia, 2010–2020.

The second Slovak PRR party, ĽSNS, also changed its distribution of electoral support. This party had in the 2010 and 2012 elections strong support in municipalities in regions with a larger Roma minority population (Gurňák and Mikuš Citation2012) - in line with the fact that the party focused on this topic. Contrarywise, it failed to succeed in regions where its main competitor, SNS, had been successful. After the party changed its themes and began to criticize the government’s regional development policy, the functioning of EU subsidies, and the functioning of the globalized economy, ĽSNS became more popular in municipalities in the Banská Bystrica region that were suffering the consequences of the economic crisis and dysfunctional regional development (Buček and Plešivčák Citation2017). This, together with the promotion of topics, such as the migration crisis, Islamophobia, or threats to traditional families, moved ĽSNS more toward Western Europe’s PRR (Mikuš and Gurňák Citation2019). These changes in topics were also reflected in changes in the distribution of electoral support for ĽSNS (). The party was successful in regions that were traditionally regions of strong support for SNS ().

There has also been a change in the distribution of electoral support for the PRR over time in Czechia (). Dawn was successful in the 2013 election in eastern Bohemia and northern Moravi – a similar spatial distribution to VV in the 2010 elections (). This was due to an overlap of topics among these two political parties – establishment criticism and support for direct democracy and referendums – as well as a change in party affiliation among some VV candidates, who became regional leaders of Dawn (Havlík and Voda Citation2016; Maškarinec Citation2017). However, when SPD was formed, it began to promote more PRR issues (e.g. the migration crisis, criticism of globalism, criticism of the European Union). This led to a loss in support for SPD in eastern Bohemia; however, its support increased throughout Moravia in old industrial and peripheral rural regions (). In the 2021 elections, SPD was also successful in northwest Bohemia, where the old industrial regions and peripheral rural regions there were suffering through a bad economic situation caused by the state of the global economy (Essletzbichler, Disslbacher, and Moser Citation2018; Kevický Citation2021). Over time, SPD gained more electoral support in regions that traditionally voted for the PRR () while still maintaining its success in some regions of Moravia where Dawn had been successful.

Table 2. Bivariate Moran’s I score for analyzed parties in Czechia, 2010–2021.

Conclusion

This article attempts to analyze the spatiotemporal (in)stability of the populist radical right in Slovakia and in Czechia. The PRR in Slovakia has strong support in regions with a predominantly Slovak population, regions with a larger Roma minority population, and some peripheral rural regions in eastern Slovakia. Areas of weak support for the PRR are those with a higher share of Hungarians. The PRR in Czechia has strong support in left-behind regions, old industrial regions with higher unemployment, as well as some peripheral rural regions. Conversely, it has weak support in the surroundings of the largest cities.

These findings are consistent with the first hypothesis, suggesting that the PRR in both countries is affected by the regions’ global, local, and historical specificities. The PRR in Czechia was successful in the country’s left-behind regions, whereas its Slovak counterpart was successful in regions with a largely Slovak population. That suggests that the PRR in Slovakia and Czechia is affected by the global specificities of regions (Essletzbichler, Disslbacher, and Moser Citation2018; Furlong Citation2019). Some local specificities of regions also affect the popularity distribution of the PRR. The first is the popularity of the PRR in peripheral rural areas. This could be because these parties celebrate the traditional rural countryside in their election programs (Forchtner Citation2019). The electoral support of ĽSNS in the 2010 and 2012 elections was strong in regions with a higher representation of the Roma minority, which agrees with the findings of Maškarinec and Bláha (Citation2014) and Mikuš and Gurňák (Citation2019).

ĽSNS also had higher support in the Banská Bystrica region, which corresponds with areas that are suffering the consequences of the economic crisis and dysfunctional regional development. The paradoxical thing is that the region’s president for some time was Marian Kotleba, whose politics contributed to the deterioration of the situation in the region (Buček and Plešivčák Citation2017). The other local specificities of regions that affect the popularity distribution of the PPR could be the friends and neighbors effect. This effect is visible in the higher popularity of SNS in the Žilina region, where the party leader, Ján Slota, was mayor of Žilina; in the higher popularity of ĽSNS in the Banská Bystrica region, where party leader Marian Kotleba was the president of the regional government; and in the higher popularity of Dawn/SPD in Moravia, where party leader Tomio Okamura was a senator from Zlín. The high popularity of the PPR in the old industrial regions suggests that the historical specificities of regions also affect the popularity of the PRR (Greve, Fritsch, and Wyrwich Citation2021).

An interesting finding is that the PPR in both countries has recently found success in areas that have traditionally had strong support for left-wing parties. This trend is visible in Slovakia’s stronger support for SNS and ĽSNS in northeastern Slovakia. In Czechia, it is visible in the stronger support for SPD around Ostrava in northern Moravia, in the old industrial regions where was concentrated coal mining and heavy industry. However, further research is needed to confirm the increasing success of the PRR in areas with traditionally strong support for left-wing parties in Slovakia and Czechia and potentially in other European countries as well.

The second hypothesis suggests that when the thematic focus of the PRR changes, the distribution of its electoral support will also change. My analysis of the spatiotemporal stability of SNS, ĽSNS, and Dawn/SPD confirmed this hypothesis. However, each of the analyzed parties had a different pattern of change in the distribution of electoral support. The traditional Slovak PRR party, SNS, had a change in the distribution of electoral support between 2016 and 2020. Between these elections the party lost its traditional centers of popularity. The main reason for the failure was the party’s inability to adapt to new issues typical of the PRR in Western Europe and the party’s participation in government, which meant that the party could not criticize the central government or EU policy. That made the party less attractive to typical PRR voters than their rival, ĽSNS. In contrast, SNS was able to succeed in regions with strong support for left-wing parties.

ĽSNS was successful in the 2010 and 2012 elections, mainly in regions with a large Roma minority population. This was because anti-Roma politics was a central party theme during that period. However, after the success of the party leader in regional elections and a shift in the critical themes of the party program to ones typical of the PRR in Western Europe, the party was more successful in other regions. Due to this, ĽSNS managed to push SNS out of its traditional regions while maintaining its popularity in regions it had had previous success in during the 2010 and 2012 elections. Like the Hungarian party Jobbik (Mikuš and Gurňák Citation2016), ĽSNS can be considered a successful example of a party that has shifted from the traditional themes of Central and Eastern Europe’s PRR to those of Western Europe’s PRR (Polyakova Citation2015; Pytlas Citation2018).

In Czechia the distribution change between Dawn and SPD is a visible transformation from a populist Euroskeptic party to a typical PRR party, similar to that of Alternative für Deutschland in Germany (Arzheimer and Berning Citation2019). In the 2013 elections, Dawn’s distribution of electoral support was more similar to that of the populist party VV than the populist radical right party DSSS. However, with the thematic change of the party, SPD has been successful in traditional regions that strongly support the PRR. At the same time, it has been able to maintain high support in some areas where Dawn had been successful, as well as areas that had traditionally shown strong support for left-wing parties.

Based on my findings, it seems that the hypotheses analyzed are valid. However, spatial analysis methods have a limiting explanatory capability. Thus, it is worthwhile in the future to further test the hypotheses with additional statistical methods to fully confirm the proposed hypotheses.

My findings may be relevant for scholars of other post-socialist countries in CEE. The rise of PRR parties in this area as well as their opinions and spatial shifts suggest that the populist radical Right in CEE is becoming more like the PRR in Western Europe. The results from Slovakia and Czechia show that spatial patterns of electoral support and the geographical dynamics of electoral change may indicate changes in the opinions and popularity of the populist radical Right. This is why studying the spatiotemporal (in)stability of PRR parties is crucial.

Acknowledgement

This work was created with the support of specific research carried out within the project MUNI/A/1393/2021 “Integrovaný geografický výzkum dynamiky přírodních a společenských procesů”. The author would also like to thank Peter Daněk and the anonymous reviewers for their inspiring comments on previous versions of this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1. The data were obtained from the Czech Statistical Office Election Server, available at: https://volby.cz/, accessed 24 January 2022, and from the Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic Election Server, available at: https://volby.statistics.sk/, accessed 24 January 2022.

2. For more information about peripheral areas in Czechia see Bernard and Šimon (Citation2017), or Jeřábek et al. (Citation2021).

References

- Anselin, L. 1995. “Local Indicators of Spatial Association - LISA.” Geographical Analysis 27 (2): 93–115. doi:10.1111/j.1538-4632.1995.tb00338.x.

- Arzheimer, K., and C. C. Berning. 2019. “How the Alternative for Germany (AfD) and Their Voters Veered to the Radical Right, 2013–2017.” Electoral studies 60: 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2019.04.004.

- Bernard, J., and M. Šimon. 2017. “Vnitřní periferie v Česku: Multidimenzionalita sociálního vyloučení ve venkovských oblastech (Inner Peripheries in the Czech Republic: The Multidimensional Nature of Social Exclusion in Rural Areas).” Sociologický časopis/Czech Sociological Review 53 (1): 3–28. doi:10.13060/00380288.2017.53.1.299.

- Bernard, J., and T. Kostelecký. 2014. “Prostorový kontext volebního chování – jak působí lokální a regionální prostředí na rozhodování voličů (The Spatial Context of Voter Behaviour: How Do Local and Regional Factors Impact Voter Decisions.).” Sociologický časopis/Czech Sociological Review 50 (1): 3–28. doi:10.13060/00380288.2014.50.1.30.

- Bornschier, S. 2018. “Globalization, Cleavages and the Radical Right.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Radical Right, edited by J. Rydgren, 311–347. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Buček, J., and M. Plešivčák. 2017. “Self-Government, Development and Political Extremism at the Regional Level: A Case Study from the Banská Bystrica Region in Slovakia.” Sociológia - Slovak Sociological Review 49: 599–635.

- Bustiková, L. 2018. “The Radical Right in Eastern Europe.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Radical Right, edited by J. Rydgren, 799–821. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Cliff, A. D., and J. K. Ord. 1981. Spatial Processes: Models and Applications. London: Pion.

- Essletzbichler, J., F. Disslbacher, and M. Moser. 2018. “The Victims of Neoliberal Globalisation and the Rise of the Populist Vote: A Comparative Analysis of Three Recent Electoral Decisions.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 11 (1): 73–94. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsx025.

- Flint, C. 2001. “A TimeSpace for Electoral Geography: Economic Restructuring, Political Agency and the Rise of the Nazi Party.” Political Geography 20 (3): 301–329. doi:10.1016/S0962-6298(00)00066-4.

- Forchtner, B. 2019. “Looking Back, Looking Forward. Some Preliminary Conclusions on the Far Right and Its Natural Environment(s).” In The Far Right and the Environment. Politics, Discourse and Communication, edited by B. Forchtner, 310–320. London: Routledge.

- Furlong, J. 2019. “The Changing Electoral Geography of England and Wales: Varieties of “Left-Behindedness”.” Political Geography 75: 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2019.102061.

- Gimpel, J. G., K. A. Karnes, J. McTague, and S. Pearson-Merkowitz. 2008. “Distance-Decay in the Political Geography of Friends-And-Neighbors Voting.” Political Geography 27 (2): 231–252. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2007.10.005.

- Giordano, B. 1999. “A Place Called Padania? The Lega Nord and the Political Representation of Northern Italy.” European urban and regional studies 6 (3): 215–230. doi:10.1177/096977649900600303.

- Giordano, B. 2000. “Italian Regionalism or ‘Padanian’ Nationalism — the Political Project of the Lega Nord in Italian Politics.” Political Geography 19 (4): 445–471. doi:10.1016/S0962-6298(99)00088-8.

- Giordano, B. 2001. “The Contrasting Geographies of ‘Padania’: The Case of the Lega Nord in Northern Italy.” Area 33 (1): 27–37. doi:10.1111/1475-4762.00005.

- Gregor, K. 2015. “Who are Kotleba’s Voters? Voters’ Transitions in the Banská Bystrica Region in 2009 – 2014.” Sociológia - Slovak Sociological Review 47: 235–252.

- Greve, M., M. Fritsch, and M. Wyrwich. 2021. Long-Term Decline of Regions and the Rise of Populism: The Case of Germany. Jena: Friedrich Schiller University Jena.

- Gurňák, D., and R. Mikuš. 2012. “Odraz rómskej otázky vo volebnom správaní Slovenska – politicko-geografická analýza (Reflection of the Roma Issues in the Electoral Behaviour in Slovakia – Political-Geographical Analysis).” Geographia Cassioviensis 6: 18–27.

- Havlík, V., and P. Voda. 2016. “The Rise of New Political Parties and Re-Alignment of Party Politics in the Czech Republic.” Acta Politologica 8: 119–144.

- Havlík, V., and V. Hloušek. 2014. “Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde: The Story of the Populist Public Affairs Party in the Czech Republic.” Perspectives on European Politics and Society 15 (4): 552–570. doi:10.1080/15705854.2014.945254.

- Jeřábek, M., J. Dokoupil, D. Fiedor, N. Krečová, P. Šimáček, R. Wokoun, and F. Zich. 2021. “Nové vymezení periferií Česka (The new delimitation of peripheries in Czechia).” Geografie 126 (4): 419–443. doi:10.37040/geografie2021126040419.

- Johnston, R. J., and C. Pattie. 2006. Putting Voters in Their Place: Geography and Elections in Great Britain. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Kallis, A. 2018. “The Radical Right and Islamophobia.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Radical Right, edited by J. Rydgren, 76–101. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Kasprowicz, D. 2015. “The Radical Right in Poland – from the Mainstream to the Margins. A Case of Interconnectivity.” In Transforming the Transformation? The East European Radical Right in the Political Process, edited by M. Minkenberg, 157–182. Londýn: Routledge.

- Kevický, D. 2021. “Prečo ľudia volia populistickú radikálnu pravicu? Geografická analýza volebnej podpory populistickej radikálnej pravice v Česku a na Slovensku (Why do People Vote for a Populist Radical Right? Geographical Analysis of Populist Radical Right Support in Czechia and Slovakia).” Sociológia - Slovak Sociological Review 53: 577–598. doi:10.31577/sociologia.2021.53.6.22.

- Kluknavská, A., and J. Smolík. 2016. “We Hate Them All? Issue Adaptation of Extreme Right Parties in Slovakia 1993 – 2016.” Communist and post-communist studies 49 (4): 335–344. doi:10.1016/j.postcomstud.2016.09.002.

- Krekó, P., and G. Mayer. 2015. “Transforming Hungary – Together? An Analysis of the Fidesz-Jobbik Relationship.” In Transforming the Transformation? The East European Radical Right in the Political Process, edited by M. Minkenberg, 183–205. Londýn: Routledge.

- Kupka, P., M. Laryš, and J. Smolík. 2009. Krajní pravice ve vybraných zemích střední a východní Evropy: Slovensko, Polsko, Ukrajina, Bělorusko, Rusko (Far right in selected Central and Eastern European countries. Slovakia, Poland, Ukraine, Belarus, Russia). Brno: Masarykova univerzita.

- Mareš, M. 2003. Pravicový Extremismus a Radikalismus V ČR (Right-Wing Extremism and Radicalism in the Czech Republic). Brno: Barrister a Principal.

- Mareš, M. 2012. Right-Wing Extremism in the Czech Republic. Berlin: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.

- Maškarinec, P. 2017. “A Spatial Analysis of Czech Parliamentary Elections.” Europe-Asia Studies 69: 426–457. doi: 10.1080/09668136.2017.1313962

- Maškarinec, P. 2019. “The Rise of New Populist Political Parties in Czech Parliamentary Elections Between 2010 and 2017: The Geography of Party Replacement.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 60 (5): 511–547. doi:10.1080/15387216.2019.1691928.

- Maškarinec, P., and P. Bláha. 2014. “For Whom the Bell Tolls: Grievance Theory and the Rise of New Political Parties in the 2010 and 2013 Czech Parliamentary Elections.” Sociológia - Slovak Sociological Review 46: 706–731.

- Mikešová, R. 2019. “Vliv lokálního prostředí na volební chování v Česku (Influence of the local context on voting behavior in Czechia).” Geografie 124 (4): 411–432. doi:10.37040/geografie2019124040411.

- Mikuš, R., and D. Gurňák. 2012. “Vývoj pozícií politického extrémizmu, radikalizmu a nacionalizmu v rôznych úrovniach volieb na Slovensku (Development of Position of Political Extremism, Radicalism, Nationalism in Different Stages of Elections in Slovakia).” Geografické informácie 16 (2): 38–49. doi:10.17846/GI.2012.16.2.38-49.

- Mikuš, R., and D. Gurňák. 2016. “Rómska otázka ako jeden z mobilizačných faktorov volebnej podpory krajnej pravice na Slovensku a v Maďarsku (Roma issue as one of the mobilization factors of voter support for the far right political parties in Slovakia and Hungary).” Geographia Cassioviensis 10: 29–46.

- Mikuš, R., and D. Gurňák. 2019. Demokraticky k autokracii? Analýza volebnej podpory krajnej pravice na Slovensku, v Maďarsku a Rumunsku (Democratically to autocracy? Analysis of electoral support of the far right in Slovakia, Hungary, and Romania). Bratislava: Univerzita Komenského.

- Minkenberg, M. 2002. “The Radical Right in Postsocialist Central and Eastern Europe: Comparative Observations and Interpretations.” East European Politics and Societies 16 (2): 335–362. doi:10.1177/088832540201600201.

- Mudde, C. 1996. “The War of Words Defining the Extreme Right Party Family.” West European Politics 19 (2): 225–248. doi:10.1080/01402389608425132.

- Mudde, C. 2000. “Extreme-Rights Parties in Eastern Europe.” Patterns of Prejudice 34 (1): 5–27. doi:10.1080/00313220008559132.

- Mudde, C. 2005. Racist Extremism in Central and Eastern Europe. London: Routledge.

- Mudde, C. 2007. Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Pink, M., and P. Voda. 2012. “Vysvětlení prostorových vzorců volebního chovaní v parlamentních volbách v České republice a na Slovensku v letech 1996 – 2010 (Explaining spatial patterns of voting behavior in parliamentary elections in the Czech Republic and Slovakia, 1996-2010).” In Volební mapy České a Slovenské republiky po roce 1993: vzorce, trendy, proměny (Electoral maps of the Czech and Slovak Republics after 1993: patterns, trends, changes), edited by M. Pink, O. Eibl, V. Havlík, T. Madleňák, P. Spáč, and P. Voda, 201–242. Brno: Centrum pro studium demokracie a kultury.

- Polyakova, A. 2015. “The Backward East? Explaining Differences in Support for Radical Right Parties in Western and Eastern Europe.” Journal of Comparative Politics 8: 49–74.

- Pytlas, B. 2018. “Radical Right Politics in East and West: Distinctive Yet Equivalent.” Sociology Compass 12 (11): 1–15. doi:10.1111/soc4.12632.

- Rydgren, J. 2007. “The Sociology of the Radical Right.” Annual Review of Sociology 33 (1): 241–262. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.33.040406.131752.

- Schulte-Cloos, J., and A. Leininger. 2022. “Electoral Participation, Political Disaffection, and the Rise of the Populist Radical Right.” Party Politics 28 (3): 431–443. doi:10.1177/1354068820985186.

- Shim, M. E., and J. Agnew. 2007. “The Geographical Dynamics of Italian Electoral Change, 1987–2001.” Electoral studies 26 (2): 287–302. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2006.05.002.

- Shuermans, N., and F. De Maesschalck. 2010. “Fear of Crime as a Political Weapon: Explaining the Rise of Extreme Right Politics in the Flemish Countryside.” Social & Cultural Geography 11 (3): 247–262. doi:10.1080/14649361003637190.

- Šimon, M. 2015. “Measuring Phantom Borders: The Case of Czech/Czechoslovakian Electoral Geography.” Erdkunde 69 (2): 139–150. doi:10.3112/erdkunde.2015.02.04.

- Stanley, B. 2011. “Populism, Nationalism, or National Populism? An Analysis of Slovak Voting Behaviour at the 2010 Parliamentary Election.” Communist and post-communist studies 44 (4): 257–270. doi:10.1016/j.postcomstud.2011.10.005.

- Steinmayr, A. 2016. Exposure to Refugees and Voting for the Far-Right: (Unexpected) Results from Austria. Bohn: IZA.

- Sum, P. 2010. “The Radical Right in Romania: Political Party Evolution and the Distancing of Romania from Europe.” Communist and post-communist studies 43 (1): 19–29. doi:10.1016/j.postcomstud.2010.01.005.

- Taylor, P. 1985. Political Geography: World-Economy, Nation-State and Locality. Harlow: Long-man.

- van Gent, W.P.C., E. F. Jansen, and J. H. F. Smits. 2014. “Right-Wing Radical Populism in City and Suburbs: An Electoral Geography of the Partij Voor de Vrijheid in the Netherlands.” Urban Studies 51 (9): 1775–1794. doi:10.1177/004209801.

- Vasilopoulou, S. 2018. “The Radical Right and Euroskepticism.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Radical Right, edited by J. Rydgren, 189–212. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Weisskircher, M. 2020. “The Strength of Far-Right AfD in Eastern Germany: The East-West Divide and the Multiple Causes Behind ‘Populism’.” The Political Quarterly 91 (3): 614–622. doi:10.1111/1467-923X.12859.

- Žatkuliak, J. 2004. “Štátopravné usporiadanie česko-slovenského štátu v rokoch 1989-1992 v kontexte jeho predchádzajúceho vývoja (The Czech-Slovak State in the years 1989-1992 in the context of its previous development).” In Desat̕ročie Slovenskej Republiky: venované jubileu štátnej samostatnosti (The tenth anniversary of the Slovak Republic: dedicated to the jubilee of state independence), edited by N. Rolková, 14–28. Martin: Matica slovenská.