?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This paper discusses intercity networks within the former Soviet Union (FSU), a semi-periphery of the global economic system of interactions. Intercity networks are constructed following an assumption that interaction between offices of the same corporation indicates connectivity between cities. In the FSU global corporations operate against a backdrop of continuous uncertainty. Consequently, it is possible to estimate temporal dynamics and spatial distribution of uncertainty by looking at the evolving structures of global companies with the example of global advanced producer service (APS) companies. These companies are regarded as brokers, integrating the region into the global business activities. The dataset comprises structures of the APS firms within the region in 2015 and 2018. A comparative analysis of networks in 2015 and 2018 demonstrates temporal dynamics of network reconfiguration and unequal spatial distribution of corporate offices in uncertain conditions. Through the lens of the network transformation, we reveal the continuous restructuring and peripheralization of the region.

Introduction

Globalization is considered by some scholars to be a manageable, unifying planetary process (Robinson Citation2002; Stiglitz Citation2018). It is not homogeneous in either time or space, however, geographical conditions, cultural contexts, and legacies play a strong role in structuring patterns of globalization (Brenner and Schmid Citation2015; Di Clemente et al. Citation2022). Considered through the prism of global information exchange (Castells Citation1997), the shifting dynamics of power and capital define cores and peripheries in the global spatial order (Kuhn Citation2015). The peripheries are to different degrees excluded from global flows and characterized by specific patterns of representation on a global scale (Saxer and Andersson Citation2019). Furthermore, outside the so-called Global North globalization is strongly structured by economic, social, and political uncertainty, resulting in unique conditions for transnational businesses (Kabiraj and Arijit Citation2019; Redl Citation2018).

Flows of capital, goods, people, and information construct globalization (Castells Citation1997), including the inequality patterns within it. The level and character of inclusion in global flows signify cores of globalization: cities and states that attract and provide the highest number of flows (Taylor, Derudder, and Liu Citation2021). However, instead of focusing on the centers here we highlight global peripheries and uncertainty, which could be considered one of the defining features of peripheral regions. We assume that exclusion from global information flows and uncertainty are mutually reproduced, leading to an increasing gap between cores and peripheries (Jimu Citation2016). The primary objective of the current study is to explore uncertainty through the (re)shaping of interurban networks in the countries of the former Soviet Union (FSU).

In this study we use data depicting the structures of the global advanced producer service (APS) companies. In a great number of globalization studies, these companies are regarded as facilitators of globalization processes, providing conditions for other global corporations to penetrate regions and states (Ben and Taylor Citation2018; Hanssens, Derudder, and Witlox Citation2013; Jacobs, Koster, and Hall Citation2011; Neal Citation2017; Taylor et al. Citation2014; Taylor Citation2001). Within each APS company, all offices are to exchange information and share common corporate values (Taylor Citation2001; Taylor et al. Citation2014). Consequently, the APS corporate structures can be considered networks of information flows, in which information exchange depicts globalization. Next, we take a step from flows between corporate offices to flows between cities, constructing the intercity network from the data on APS offices’ locations. We merge the flows of information between offices and assume that they construct flows of information between cities. As a result, we are able to introduce a spatial dimension to the virtual flows and geographically estimate globalization patterns.

Uncertainty as a condition imposes chaos and unpredictability on strategies of global businesses, and consequently on economic globalization itself. The “peaks” of uncertainty are observed in global peripheries, where unstable political regimes, social conflicts, and relatively low efficient economic performance coexist (Jimu Citation2016). These are regions of both high profit and high risk for global service companies. In this paper, we shed light on how APS firms’ structures reveal uncertainty in the FSU states, where a high level of uncertainty has been observed since the dissolution of the USSR (Muller and Trubina Citation2020b). We employ interurban networks as frameworks that mirror the uncertainty within the region. The APS companies adjust their structures to local conditions by actions such as leaving some countries, decreasing the number of functions in some offices, creating separate branches to operate simultaneously in two countries. The patterns of interurban networks are assessed based on 2015 and 2018 data on the office locations of APS companies.

The paper consists of seven sections. First, we present the theoretical background for studying interurban networks. Second, we discuss the regional context. Third, we indicate the data, and fourth, the methodological approach. The remaining sections provide the results, discussion, and conclusions.

Theoretical background

To reveal the structure of the uncertainty within the FSU, we adopt the World City Network (WCN) approach, which is rooted in the idea of globalization itself. Globalization and new technologies that boost it are viewed as weakening the “national as a spatial unit” and intensifying cross-border economic interaction, whereby cities become the focus of activities (Sassen Citation2005). The flows of goods and information continuously increase, creating new formats of global networks and calling for new approaches to research methodology in globalization studies (Coe and Wai-Chung Yeung Citation2015; Ben and Taylor Citation2018). Against this background, researchers are paying increasing attention to various types of flows that can be isolated within interurban networks (Derudder, Devrient, and Witlox Citation2007; Neal Citation2018; Sigler and Martinus Citation2017; Taylor Citation2013; Yang et al. Citation2018; Zook Citation2018). A broad variety of researched intercity flows can be divided into two groups: material and virtual. Material flows involve the relocation of physical objects: goods and people. Virtual flows are defined as flows of information and capital (Ben and Taylor Citation2018). In globalization studies both material and virtual flows can be employed in order to construct intercity networks (ibid).

The WCN approach, widely known in the study of global urban networks, focuses on virtual intercity flows created by the offices of global service companies. It aims to uncover the unique ability of globalization to shape and restructure intercity connections, emphasizing inequality and imbalance among cities in their attractiveness to global companies (Ben and Taylor Citation2018; Taylor and Derudder Citation2015; Taylor Citation2013). It highlights “how rather than if cities are global” (Sigler and Martinus Citation2017, 2916). As a research model, WCN is designed to compare the level of inclusion of cities in the pre- and post-production stages of the global value chain. The networks are principally structured as relative, being defined as both structure and process, built based on the relative significance of each office in the corporate network, and researched through the lens of hierarchy and interaction (Dicken et al. Citation2001; Sigler and Martinus Citation2017; Taylor and Derudder Citation2015; van der Knaap Citation2007).

Existing research on global interurban networks is predominantly focused on the most connected elements on the global scale: cities of the Global North. Unfortunately, cities in the Global South and those in-between ones (e.g. the Global East) remain understudied (Muller and Trubina Citation2020a; Robinson Citation2002; Roy Citation2009). Thus, the focus on the cores of global interaction has influenced the perception of globalization as a process worldwide. The new pattern of interaction, provided by the global market, was expected to overcome state borders and level off path dependencies. This assumption is based mostly on the researched cases from the Global North, where globalization seems to be less impacted by uncertainty and where the political and economic situation seems relatively stable (Beck Citation2016; Friedman Citation2005; Ohmae Citation1990, Citation2000; Kobrin Citation2001). Thus, the perceived core globalization outposts, like New York and London, are expected to break off their hinterland and become the centers of decision-making for global businesses (Hoyler Citation2011; Massey Citation2007; Sassen Citation1991).

Leo Tolstoy said “happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way”, and countries outside the Global North demonstrate high diversity in globalization patterns. We cannot claim that some regions or states are excluded from globalization, rather, they are differently connected. And this involves not only illegal practices of international crime (Saxer and Andersson Citation2019) but also specified inclusion in the structures of global APS corporations. Even the cores of WCNs experience diverse patterns of involvement in the structures of the APS firms, depending on their specialization (Ben and Taylor Citation2020). For the peripheries, the character of embeddedness of places in globalization is significantly more turbulent, corresponding to the theoretical framework of “space of flows” as a constantly changing structure (Rantanen Citation2005). The demand for the pluralistic and critical research of globalization is becoming more pronounced (Ben and Taylor Citation2020), accompanied by a general perspective of stepping beyond the “Northern gaze” and overcoming the dichotomy of the developed and the developing world (McEwan Citation2019; Peck and Theodore Citation2007).

Contemporary research emphasizes the multiplication of borders and the historical approach to the individual tracks of regions and cities (Ceglowski Citation2000; Kobrin Citation2017; Loginova et al. Citation2022; O’Dowd Citation2010; Paasi Citation2019). Regional studies observe cultural similarities/differences, the influence of politics, and path dependencies in globalization (Antoine, Sillig, and Ghiara Citation2016; Derudder and Witlox Citation2008; Hoyler Citation2011; Pan et al. Citation2017; Wall Citation2011). Addressing simultaneous globalization and localization, researchers consider the complicated structure of globalization in which the cores and peripheries are relative and dynamic (Ben and Taylor Citation2020). The theoretical dichotomy of global and local is transformed into a mutual embeddedness of scales (Ben and Taylor Citation2020). Consequently, the local and regional perspectives construct not only the patterns of globalization within regions but also the general process of globalization, contradicting the perception of globalization as a unified and unifying condition. The image of globalization as intricate and turbulent becomes more relevant. And uncertainty, being a distinct feature of the global peripheries, determines the complexity of globalization worldwide.

The current paper considers uncertainty as a result of the complicated interplay of economic, political, and societal factors and as an important feature of the Global South and Global East. In political studies, uncertainty is typically referred to as a characteristic of a certain political regime, where the work of institutions and policy-making processes are barely predictable (Kenyon and Naoi Citation2010; Lupu and Beatty Readl Citation2012). In sociology, uncertainty is defined as the random environment, where events cannot be logically interpreted or foreseen and societies are accustomed to fear and unpredictability (Simon Noah Etkind et al. Citation2017; Goode, Paul, and Stroup Citation2022). The sprawl of urban legends and rumors, for example, highlights the need to make sense of the situation and overcome anxiety during the senseless condition of uncertainty (Arkhipova and Kirziuk Citation2020; DiFonzo and Prashant Citation2011). In economics, uncertainty is considered an obstacle to prognosis and modeling. In the condition of uncertainty, probabilities of diverse outcomes cannot be estimated based on facts. As Davidson puts it, “uncertainty about future relationships can be defined in terms of the absence of governing ergodic processes” (Davidson Citation1988, 332). He also distinguishes between uncertainty and risk, regarding uncertainty as stochastic and unpredictable (ibid). In business studies, uncertainty is addressed as the array of separate unpredictable conditions, concerning local cultures of doing business and consuming, politics and legislation, currency rates, and macroeconomic vulnerabilities (Ahsan and Musteen Citation2011).

Aggregating the four approaches from different disciplines, we can describe uncertainty as a sense of continuous emergency when legal, political, social, and economic conditions can change quickly and in a disorderly manner. Unlike shock, uncertainty is a lasting process; this is why it is capable of reproducing itself. However, uncertainty differs from path dependence as it is based on disorder and unpredictability. Uncertainty is widely discussed in the fields of economics, sociology, mathematics, and political science (Amin Citation2011; Carmignani Citation2003; Davidson Citation1988; Jost Citation2017; Wensheng, Ratti, and Vespignani Citation2020; Kenyon and Naoi Citation2010; Lupu and Beatty Readl Citation2012; Mainwaring and Zoco Citation2007; Muller and Trubina Citation2020b; Redl Citation2018; van der Knaap Citation2007) but has not yet been studied as a complex interdisciplinary concept.

When addressing globalization through the lens of uncertainty, we question the unified character of global interaction. In this regard, the WCN approach offers a path toward revealing how uncertainty in states and regions makes global networks intricate and turbulent. Social tensions, political decisions, and economic shocks transform the structure of cores and peripheries at a regional level and shape the unique patterns of global flows. “The last shall be the first and the first last” in the network reconfiguration, and it can be chaotic and unpredictable. The obstacles to the flows in the conditions of uncertainty lead to a reconfiguration of entire networks. Uncertainty empowers the representation of borders and the spatial aspect of globalization in networks, as institutions, societies, and companies are regulated locally, and during uncertainty this regulation is unbound from the customary business practices of global corporations (Ahsan and Musteen Citation2011; Gurkov Citation2020).

Uncertainty in relation to the FSU is predominantly studied as an outcome of the state socialism collapse. Guillermo and Schmitter (Citation2013) define this situation as “extraordinary uncertainty”, when the future is completely unpredictable – one order is gone while another is not yet defined. As argued by Jost (Citation2017), experiencing this kind of uncertainty leads to an increase in conservative views among citizens. For the FSU, conservatism inevitably appeals to the Soviet past, and promotes nationalism, local conflicts, and military unrest (Chen Citation2020; Solt Citation2011). The post-Soviet period is also characterized by the rise of economic inequality (Aghion and Commander Citation1999). Taken together, nationalism and economic inequality continue to fuel local conflicts, creating even more uncertainty and further sprawl of conservative ideas. As a result, uncertainty in the FSU becomes a proliferating condition, reinforced in a vicious circle.

Applying the WCN approach in research on both globalization and uncertainty is rooted in Manuel Castells’s idea of space of flows (Castells Citation2020). Talking about the intensification of flows in the Information Age, Castells highlights the dynamic and non-linear character of globalization. Consequently, the networks depicting globalization are also expected to be turbulent and diverse (Rantanen Citation2005). Meanwhile, contemporary network studies are largely determined by the idea of preferential attachment, which involves an increasing connectivity of central nodes, while the network is expanding. The networks determined by preferential attachment are highly predictable, and demonstrate a distinct division of cores and peripheries (Gao, Zhang, and Zhou Citation2019; Barabási Citation2010). In the situation of “rational” choices, when economic benefits are the leading power in every political decision (Polanyi Citation1945), interurban network structures should be determined by preferential attachment. However, the existence of preferential attachment in networks created by global trade has been repeatedly tested with diverse outcomes (Xiang, Ying Jin, and Chen Citation2003; Linqing Liu, Shen, and Tan Citation2021; Linqing Liu et al. Citation2022; Serrano and Boguná Citation2003). The contradiction between mathematical rationality and “real-world” structures in global networks can be addressed through the prism of uncertainty. It is typically uncertainty that is employed as the factor of unpredictability in economic modeling (Gao, Zhang, and Zhou Citation2019), but it has not been studied particularly as a spatially and temporally specific process.

Obscurity of urban hierarchies, spatial fragmentation of economic interactions, and lingering conflicts around unrecognized states (South Ossetia, Nagorno-Karabakh, Abkhazia, Transnistria) (Souleimanov, Abrahamyan, and Aliyev Citation2018) underpin the uncertainty that exists in the FSU, with chaotic restructuring being one of the basic characteristics of the network we observe here. Following the collapse of the USSR, a large share of the FSU states grew their autocratic regimes, with some facing military unrest, further collapse, aggression, and irredentism. Autocracy and hypercentralization define the concentration of the governing functions in capitals and the superiority of top-down mechanisms. The conservatism and nationalism that emerged in the 1990s are reproduced in contemporary politics (Beacháin and Polese Citation2010; Kuzio Citation2001).

Regional scope

This study adopts the World City Network (WCN) methodology to uncover the internal structure of intercity networks within the FSU. From the viewpoint of both globalization studies and interurban network research, the FSU is a geographical region subjected to double exclusion: “neither center nor periphery, neither mainstream nor part of the critique” (Tuvikene Citation2016, 1). A strive for control over space, estrangement and dispossession, inequality, and top-down decision-making are emblematic of most of the post-Soviet region, being in part pre-defined by Soviet urbanization and industrialization patterns.

Rapid industrialization in the USSR, regulated by centralized planning, led to a fast-paced rise in urbanization. The share of urban population in the USSR rose from 17% in 1926 to 66% in 1989 (Gosudarstvennii Komitet SSSR po Statistike Citation1990; Khoziaystvennogo Ucheta Gosplana SSSR [Central Office of National Economic Accounting of the State Planning Committee of the USSR] Citation1934). However, urbanization was underpinned by mass rural–urban migration, which brought the rural way of life into cities, defining the course of modernization policies that lacked the imposition of an urban lifestyle and urban self-governance (Frost Citation2018; Zubarevich Citation2012).

Soviet urbanization was strongly shaped by ideology. During the Soviet period, cities were an essential part of space production. The idea of industrialization, exceeding capitalist countries, and global communism defined Soviet city-building (Gerlach and Kinossian Citation2016; Golubchikov Citation2017). Simultaneously, the idea of overcoming geographical conditions and a disregard to distance pushed Soviet urbanization to the margins of the country and supported the growth of state company towns (Zubarevich Citation2012). The illusory control over space remains in the post-Soviet discourse, repeatedly employed in planning and investment programs (Batunova and Gunko Citation2018). Concentration of production, control over internal migration, and unification of urban space caused an “atomization” of cities, making them “small islands or archipelagoes in the ocean of the Russian periphery” (Nefedova and Treivish Citation2003, 80; Frost Citation2018). A low density of cities led to estrangement during the post-Soviet period, both between and within the states.

During the Soviet period, equality in supply and distribution of all goods was declared but was not achieved in reality; it greatly depended on the “strategic significance” to the state of a location or social group. “Departmental distribution” legitimized social inequality despite ideological conditions and forced the shadow schemes of distribution at all levels of supply chains (Osokina Citation2008; Pervushina Citation2012; Truschenko Citation1995). The inequality, that currently exists in the FSU, has been partly inherited from the Soviet system of “planned inequality”. It is the least pronounced in the Baltic states, which spent the shortest period in the USSR and the most explicit in Central Asia, which was industrialized during the USSR period.

The conditions of Soviet urbanization, unique to some extent, lay the ground for the post-Soviet urban transformation. Economic restructuring, changing political institutions, and social interactions have made urban issues into a special dimension of the post-Soviet transition (Golubchikov Citation2017). The Soviet economic interaction, determined by industrial planning and state-led hierarchy, witnessed a rapid and radical transformation, just like the political regime and society’s constitution did after the USSR’s collapse (Golubchikov Citation2017; Hirt, Ferencuhova, and Tuvikene Citation2016). During the Soviet period interurban ties were affected by the planned economy. Since the collapse of the USSR, most of these ties have been ruptured or significantly reshaped by the market transition and violent conflicts. New interurban connections have been established by the global corporations, yet they partly replicate the Soviet model (Golubchikov Citation2017; Loginova et al. Citation2020). A diversity of political regimes and a significant number of conflicts within the space have impacted the post-Soviet urban hierarchy and networking, making it extremely complicated. Scholars argue that, in the last three decades, post-socialist cities and their networks have faced uncertain conditions more than most others have (Muller and Trubina Citation2020b). Adopting a market economy, transforming political regimes and waging wars with one another, countries of the former USSR constitute a unique environment for the performance of global corporations that is both attractive and unpredictable (Rogov and Rozenblat Citation2022).

In the current research, we estimate the extent to which the FSU cities are connected by the globalized flows of information and trace the dynamics of this connection. By comparing the existing urban networks to quasi-random ones, we consider and classify the ongoing trend between integration and dissolution. Estrangement, inequality, illusory control over space, and a supremacy of top-down decision-making are the characteristics of the FSU, shaping the pattern of uncertainty as a condition and a process. During uncertainty, the cross-border operations of global companies become more complex. Simultaneously, global corporations might grow into mediators, overcoming uncertainty through economic ties. These actions are expected to transform the unique and complicated political environment into a more unified, controlled area within the global system.

Research method

As part of this research, a database of global APS companies in FSU was created; with the delimitation of the region being the first step of the data collection. The EU and NATO membership of the Baltic states serves as a considerable reason to exclude them from the analysis, as an aversion to the Soviet legacy must be a condition for the region delimitation. However, as Holland and Derrick (Citation2016) highlight, the antagonism to the Soviet legacy is a product of the post-Soviet experience. Consequently, relying on the context of the study (Agnew Citation2012), the former USSR region is observed as a whole; thus, the data covers 15 countries.

The data merges the structures of global advanced producer service (APS) companies operating in the FSU. As one of the research aims was to discuss the performance of the global actors at the local level, the global APS companies were chosen as the actors that were clearly addressing, employing, and representing globality as not just a condition but a goal. Being considered as brokers of globalization, these companies also exploit their international character to attract employees and clients (Baldwin Citation2016). Mazzucato and Collington (Citation2023) highlight the interface between consultancy service companies and the idea of contemporary capitalism and neoliberal development. Observing the clients of global consulting companies, they reveal that not only private businesses but also governments and intergovernmental organizations are among the major clients of these companies. Being usually involved in the design of neoliberal transformations, global consulting companies are among the constructors of the unified global market (Mazzucato and Collington Citation2023). Global APS companies are also deeply involved in shaping the pattern of globality through supporting the cross-border flows of information, capital, values, goods, and labor (Baldwin Citation2016; Taylor Citation2001). The current paper critically addresses APS companies as brokers of globalization, revealing the impact of local conditions on their localization patterns and questioning their position in-between global and local scopes. Overall, it was the globality of the companies’ operations that shaped the pattern of the data collection and analysis. To be included in the database, a company had to meet three requirements:

operate in the sphere of business-to-business services;

operate globally (be included on the Forbes List or other specialized list of global companies); and

have at least one office physically located in the FSU.

Data on the location of each corporate office of each company meeting the requirements was collected from the corporate websites. Addresses of the offices, providing contacts for corporate clients, were used to construct the database. We assumed that global APS companies, being interested in interaction with their clients, keep their contacts up to date. The data was collected for two time periods, 2015 and 2018, and the collection was done in relation to APS firms operating in six sectors: accountancy, advertising, banking, insurance, law, and management. These sectors create conditions for the inclusion of corporations with other specializations in regions and their immersion in the process of globalization (Taylor Citation2001). The vast majority of the selected companies did not originate in the FSU or other post-socialist states. One particular exception to this is Sberbank, with its headquarters in Moscow. During data collection, its offices were classified based on their specialization, and only those operating both internationally and with corporate clients were included in the network. One originally Polish insurance company is also represented in the network (headquarters in Warsaw).

The number of companies in each sector was limited to 16, making it easy to compare the sectors. Unfortunately, due to a number of corporate mergers in 2018, only 14 companies were present in the advertising sector, distorting the general research design. The companies were chosen primarily from the Forbes Global 2000 List. In 2015, some other sector-specific rates were also employed in the data collection (Frost and Podkorytova Citation2018). The research design, similar to that suggested by P. Taylor and the GaWC Group (Taylor Citation2001; Taylor et al. Citation2014), is based on a limited list of cities. Obviously, at a global scale, it is not possible to consider the entire variety of cities worldwide. However, in a territory that is involved in the globalization process only to a limited degree, it is feasible to restrict the number of companies. The list of cities in this paper was formed according to where the corporate offices were located. If at least two offices of different global APS firms happened to be in the same city, this city was included in the dataset.

Following Taylor’s (Citation2001) approach, the significance of every office within the corporate structure was rated from 1 to 5. However, the scoring system was adjusted to both regional scale and unique characteristics of each sector within the region. A rating of 5 was applied if the office served as regional headquarters, and 1 was used for offices with a limited number of functions, while the other scores described intermediate situations. The results were shaped into a city-APS firm matrix. Next, the regional network connectivity (RNC) was calculated and analyzed using a stochastic degree sequence model (SDSM).

The research adopts an interlocking network model (INM), created by P. Taylor (Citation2001) and widely applied by scholars in order to provide a detailed structure of interurban cooperation and competition in globalization (Ben and Taylor Citation2018; Hoyler Citation2011; Luthi, Thierstein, and Hoyler Citation2018). The INM was adjusted to the regional scale of the FSU in 2015 as an RNC measure (Frost and Podkorytova Citation2018). The RNC for the city-firm matrix is calculated as follows:

where j is a company, a is a specific location, for which the connectivity is calculated, and i is a set of the cities in the matrix. From a graph point of view, RNC is similar to the node degree centrality measure.

Each pair of connected cities is labeled an edge or a dyad. The dyad connectivity for each pair of cities was counted as the sum of connectivities for all firms present in both cities. In the current approach, the existence of an interconnection between two offices of the same company was assumed. The uncertain conditions were regarded as implicitly forcing actors (in our case, offices of the global companies) to cooperate and exchange information while facing the challenges of a volatile and somewhat hostile environment.

As Neal (Citation2017) justly highlights, the observed measure of connectivity itself does not provide enough information to draw conclusions as to the intensity of interaction between cities. Consequently, Neal proposed the stochastic degree sequence model (SDSM) to emphasize the comparative framework of the urban network research and substantiate analytical opportunities of research in WCN. In general, the SDSM answers the following questions: “How well are cities in the network connected? Is their performance better or worse than in the random graph in similar conditions?” (Neal Citation2017) When applying the SDSM, we compare the actual networks to hypothetical environments, in which each company chooses its office localization based only on the localization structures of other companies.

In order to ensure that the SDSM was employed accurately, we calculated the number of corporate offices of each type for each firm and each city. Based on these measures, we built an ordered logistic regression model to compute the probability of each company opening an office in each city. The ordered logistic regression is a generalization of traditional logistic regression, which allows the outcome to be ordinal rather than binary. In our case, the ordinal outcome is an observed size of firm j in the city a and ranges from 0 (no office) to 5 (regional headquarters). An ordered logistic regression model was estimated using the polar function of the MASS R package. The set of counted probabilities was used to construct a thousand quasi-random networks for each of the 2015 and 2018 datasets. After this, the interlocking WCN approach was applied to each of the two thousand matrixes. The RNC and dyad connectivity were calculated in each of the quasi-random networks (Neal Citation2017).

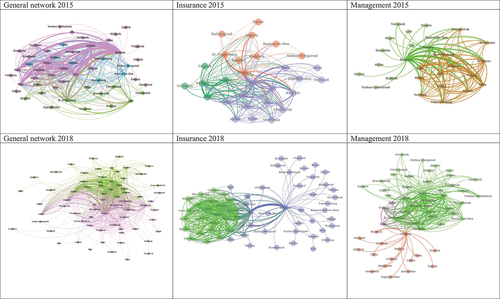

The network approach is structured and employed as a relative and subjective methodology. It is up to the researcher to delineate the network, divide data between edges and nodes, choose the focus of analysis and way of visualization. This predefines diverse and complex outcomes for the readers. The relativity, subjectivity, and technical focus of the network approach are both a strength a matter of critique (Knox, Savage, and Harvey Citation2006; Neal Citation2017; Neal, Domagalski, and Sagan Citation2022). In the current paper, we employ modeling and probabilities applied to the entire network structure and focus on visualizing networks through mapping the node degree centralities (or RNC) (see ). Thus, we reveal the spatiality and consistency of the analysis and representation highlighting the dynamics of network structures. However, in the Appendix (see Appendix 1) we also employ a more widespread approach to network representation, which complements the research design and emphasizes the inequality existing in the networks.

Networks of global APS companies in the former USSR

As long as the approach to the data collection does not restrict the number of cities within the network, the size of network is a significant outcome in itself. The network included 61 cities and 96 APS firms in 2015, and 102 cities and 94 APS firms in 2018. A considerable increase in the number of cities in 2018 was observed in the largest FSU countries: Kazakhstan, Russia, and Ukraine. Additionally, significant sprawl was noted in Lithuania. The number of dyads within the datasets increased from 1,298 in 2015 to 2,993 in 2018. The network became denser in 2018, with the average number of edges per node increasing from 21 to 29. Nonetheless, the average connectivity of nodes and dyads decreased. illustrates the spatial distribution of node connectivity in the FSU in 2015 and 2018.

Despite the growth of the network between 2015 and 2018, the patterns of involvement became more diverse for different states and different sectors. Also, the subregional diversity and the significance of state borders became more pronounced. During the analysis of the 2015 network, varied patterns of involvement in different sectors were noted. The studied sectors were divided, based on the configuration of the involvement of cities, into three groups: strategic (advertising and law), ubiquitous (accountancy and management), and hybrid (banking and insurance) presence. Companies with strategic presence tend to have a small number of offices, predominantly in capital cities. The dominance of Moscow in this sector is overwhelming. The offices of these companies are spatially concentrated even within the city. On the other hand, as many companies are represented only in the Russian capital, they do not provide connectivity, and the networks for these sectors are quite small. Meanwhile, companies with ubiquitous presence provide the most dense and broad networks. The size of economy and population are the most significant features for the localization of these companies, and some of them tend to incorporate successful local firms into their structures. Both companies with strategic and with ubiquitous presence operate in sectors with hybrid presence (Frost and Podkorytova Citation2018). The witnessed trends in 2018 strongly correspond to the classification above. demonstrate node connectivity sector by sector in 2015 and 2018.

Figure 2. Spatial distribution of the regional network connectivity for companies with strategic presence in 2015 and 2018.

For companies with strategic presence, the network essentially shrank or became fragmented (see ). The most striking change was observed in the network of law companies, with the number of cities in the set having halved by 2018. In the advertising sector, the number of cities increased, although the average connectivity of a node plunged from over 400 to 247. The companies with ubiquitous presence demonstrated a negligible increase in the number of cities and a marginal decrease in average node connectivity (see ). The major network sprawl in 2018 was caused by the soar in the number of cities in sectors with a hybrid presence (see ). The average node connectivity also rocketed in the banking sector, while in insurance it remained relatively stable. Both in networks with ubiquitous and with hybrid presence, the significance of borders is more pronounced in 2018 compared to 2015. The unbound nature of Ukrainian cities is observed in the banking sector, while in insurance and management the Russian cities tend to grow more connected to one another. The increasing interaction within the state, accompanied by decreasing cross-border interaction, contradicts the general perception of globalization as overcoming borders and empowering a unified business environment (Allen Citation2003; Fukuyama Citation2006; Kobrin Citation2017; Sassen Citation1991, Citation2005). This can be regarded as an outcome of uncertainty, which complicates and distorts the cross-border business processes.

Figure 3. Spatial distribution of the regional network connectivity for companies with ubiquitous presence in 2015 and 2018.

Figure 4. Spatial distribution of the regional network connectivity for companies with hybrid presence in 2015 and 2018.

We consider the revealed trends to be aspects of a reconfiguration of APS firms’ presence in the FSU. The key features of this reconfiguration are its spatial and sectoral patterns. The remarkable expansion in the sectors with hybrid presence is a peculiar outcome of an actual network reconstruction. The hybrid presence includes both companies with ubiquitous and with strategic patterns of localization. Consequently, if global leaders within a certain specialization leave a space, the share of corporations focusing on ubiquitous presence increases and network sprawl is observed. Namely, the shortage of world-leading insurance companies with strategic presence transformed the regional balance. With regional branches of EU insurance companies with ubiquitous presence in Ukraine and Moldova included in the data instead, the positions of local cities strongly improvedFootnote1.

As for spatial reconfiguration, this was observed in the three largest economies of the region: Russia, Ukraine, and Kazakhstan. Against the backdrop of the conflict between Russia and Ukraine, international companies are forced to either increase their presence in the region or leave it, since cross-border interaction between the leading locations, Moscow and Kiev, is complicated. The growth in the number of Chinese companies and their activity in Central Asia led to an increase in the role of Kazakhstan in the intercity network. Generally, we observe spatial fragmentation, reflecting the uncertainty within the region. Due to uncertain conditions, leading APS firms with strategic presence leave the former USSR space, while companies with ubiquitous presence mirror the division of FSU into separate subregions. As a result, the FSU is growing into a more peripheral region for global businesses and the new fractal peripheries are shaped within it.

The network graphs, provided in the Appendix (see Appendix 1), demonstrate how both the general network and the networks for management and insurance are becoming fragmented, creating a diverse and turbulent image of the space. The graphs represent cores of the networks, where cities are assumed to be densely connected to each other and connectivity should be increasing. However, the internal borders of the region are becoming more pronounced by 2018, and the estrangement between Russia and other countries of the region is observed.

Also, some intrastate borders are reflected in the network graphs. For example, Almaty and Astana are usually located in different clusters within the graph, reflecting not only competition between the former and current capitals of Kazakhstan but also discord between the north and south of the country (Thomas Citation2015). The major authorities, located in Astana, empower Moscow-based companies with strategic presence to interlace the city in their corporate networks. While the entire project of Astana was designed to promote Kazakhstan globally (Fauve Citation2015), Almaty still occupies the core position in the networks of the global APS companies. This highlights the fact that Kazakhstan predominantly attracts global APS firms with ubiquitous presence, which favor local private clients to local authorities and Almaty to Astana.

Our further observation will be devoted to the SDSM’s implementation, which has been mostly focused on localizing the extreme cases of over- and underconnected nodes and edges. In this part of the analysis, we compare the actual networks with the thousand quasi-random ones, provided for each of the 2015 and 2018 datasets. We estimate the efficiency of nodes and edges as the share of quasi-random networks, in which the connectivity of the studied nodes and edges is lower than in the actual networks. First of all, we consider the edges that stand out as most and least effectively connected in 2015. As for 2015, only 4% of edges (49 of 1,298) demonstrated higher connectivity in the actual dataset than in 95% quasi-random networks. The number of dyads with connectivity lower in the actual graph than in 95% of the quasi-random networks was 12, or 1% of 1,298. Therefore, the number of strongly overconnected dyads is four times higher than that of strongly underconnected ones. Second, we similarly estimate the connectivity of nodes in 2015. Surprisingly, only Tashkent demonstrated the highest efficiency with actual node connectivity, higher than in 94% of the modeled networks. Meanwhile, for Moscow, Sumi, and Ternopil, the node connectivity in 95% of the modeled networks was higher than in reality. The cases of Sumi and Ternopil seem natural, as these cities have low connectivity and are poorly integrated in the network, forming a periphery within the FSU. However, the case of Moscow which in the vast majority of the modeled networks had higher node connectivity than in the actual one is especially significant. It turns out that the most connected node within the network does not perform efficiently at all; in most of the random cases it showed better results.

In the 2018 network, the share of dyads with connectivity that was higher in the actual graph than in 95% of the quasi-random networks increased to 5% (144 out of 2,993). Likewise, the share of edges with connectivity that was lower in the actual graph than in 95% of the quasi-random networks reached 2% (58 out of 2,993). The balance between strongly overconnected and underconnected dyads shifted in favor of the latter. Among the nodes, the most efficient performance in 2018 was demonstrated by Chisinau instead of Tashkent (higher in actual network than in 93% of the quasi-random networks). Moscow performed slightly better than in 2015, although only 6% of the quasi-random networks had lower connectivity than its actual index. This increase is regarded to be a result of Russian cities’ greater involvement in networks in 2018. Riga, Vilnius, Almaty, and Yerevan had node connectivity in 95% of the quasi-random cases higher than in the actual network. The number of inefficient nodes increased; most of them were rated high in total connectivity, and most of them are capital cities. In general, in 2018 the network became more polarized, with a higher share of extreme cases as well as a higher number of edges and nodes. We consider this to be an argument in favor of a growing space fragmentation due to the complexity of interstate relations. In general, we can see how the network transformed between 2015 and 2018, and the efficiencies were redistributed. The only stable trend is the outstandingly low efficiency of Moscow as a node. This finding highlights the fact that the network is not only becoming more fragmented but is also chaotically falling apart, illustrating that uncertainty is a characteristic of the region.

Further sophisticated analysis of a set of dyads with high efficiency (better connected than in 95% of the quasi-random networks) was performed. Among these dyads, the following specific types were noted. First, dyads connecting capital cities were studied. It is widely assumed that capital cities detach themselves from their surroundings and interact mostly with other capitals (Hoyler Citation2011; Massey Citation2007; Sassen Citation1991). Then, the dyads connecting cities of the same countries were considered in order to verify the hypothesis of post-Soviet space fragmentation. If the share of such dyads among the most efficient ones is significantly higher than in a random sample, this could be assumed to be an argument in favor of space fragmentation. Comparing a real network with our random model, we acted on the presumption that the two are equal if the numbers of edges and nodes in them are the same. It must be said that it was our plan that all the nodes within the studied groups (capitals and cities within the same countries) would be connected. Then, we estimated the expected value for each group of dyads and its share within the sample. demonstrates the results. The actual share of capital-to-capital dyads and dyads between Ukrainian cities strongly exceeds the expectation in both 2015 and 2018. Meanwhile, for Russian cities as well as all the cities within the same country, this happens only in 2018.

Table 1. Expected and real shares among the most efficiently connected dyads.

In 2018, the share of dyads between cities in the same country exceeds the expectation, demonstrating another scope of spatial fragmentation. The real share of capital-to-capital dyads is five times higher than expected in both 2015 and 2018. While the expected increase in the gap between capitals and their surroundings is not observed, the network fragmentation by country is significant and increasing. So, this is not simply an illustration of the borders not being erased by globalization; in the region of the former USSR, the significance of state borders is increasing and the local is prevailing over the global.

Unfortunately, the precise pattern of fragmentation cannot be traced in the FSU. However, the analysis of cases has been performed to shed light on the fragmentation patterns. The exclusion of Ukrainian cities from the FSU intercity networks is visible in the precise analysis. The case of Kharkiv is a distinct illustration of this process: In 2015, Kharkiv was listed among the low-efficient nodes with real connectivity higher than in the modeled ones in only 6% of cases. It was also repeatedly represented in the least efficient dyads with FSU capitals (Almaty, Baku, Yerevan, Riga, Vilnius, Tallinn, and Astana). It was represented in the most efficient dyads twice, with Lviv and Odesa. In 2018, however, the Kharkiv’s position in the network changed dramatically. Its efficiency as a node increased, and in 50% of cases was higher than in the quasi-random networks. It was involved in only one of the least efficient dyads (Kharkiv-Tashkent) and in 10 of the most efficient ones, all with Ukrainian cities (Lviv, Kyiv, Odesa, Dnipro, Zaporizhzhia, Vinnytsia, Zhytomir, Uzhhorod, Ivano-Frankivsk, and Poltava). Like many other Ukrainian cities, it witnessed a breaking of connections with Russia and a rise of a local interurban network. In this case, the mechanics of uncertainty shaping the network are visible: Political decisions make cross-border interaction too complex, and companies are forced to choose between Russia and Ukraine. Having a smaller market, Ukraine is less attractive to the global APS firms, which aim to operate for the entire region. As a result, Ukraine engages corporations with more local ambitions that are more interested in the intrastate market than in the entire FSU.

The positions of capitals in the network have also transformed. Further, we observe a traditional subregional division for USSR peripheries including Baltic states, eastern European states, the Caucasus, and Central Asia. These groups of countries demonstrate diverse trends in connectivity. We performed a micro-analysis of node centrality through the SDSM for the capitals, and it turned out that there are two subregions with highly similar trends in the measure and two with significant diversity (see ).

Table 2. Efficiency of connection compared to the same dyads in quasi-random networks, percent (0 – all quasi-random dyads had higher connectivity, than the actual one, 100 - all quasi-random dyads had lower connectivity, than the actual one).

For Caucasian and Central Asian capital cities, the trends are mostly similar. The efficiency of inclusion in global flows for these states decreases dramatically, and they are constructing new “peripheries within peripheries”. Conflicts and political disturbances in each subregion (see the website of the Uppsala Conflict Data Program) bring about the increase of uncertainty and the decrease of inclusion in the global flows. In Eastern European and Baltic capital cities, the trends are more diverse. Among Eastern European cities, Kyiv and Chisinau demonstrate the same pattern, while Minsk goes the opposite way. However, the entire analysis experience does not reveal a sustainable similarity between Kyiv and Chisinau’s connectivity, which might be a result of the significant difference in their size. Among Baltic capitals, Riga and Vilnius always show highly similar results by any measure, while the results for Tallinn are slightly different each time. We can assume that Tallinn has been growing into a hub between the EU and the FSU. Generally, rapid and largely chaotic network reconfiguration and low efficiency in Moscow reiterate the uncertainty currently present within the FSU.

Discussion

Evaluating intercity networks reveals the fragmentation of the FSU as an ongoing process. Along with a growing gap between cores and peripheries within each country, found in several globalization studies (Hoyler Citation2011; Massey Citation2007; Sassen Citation1991), we also observe an increasing gap between countries. Late-1990s and early-2000s studies in globalization considered state borders to be in the process of being erased by global flows (Allen Citation2003; Beck Citation2016; Clapham Citation2002; Friedman Citation2005; Kobrin Citation2001; Ohmae Citation1990, Citation2000) or disaffected by them (Kobrin Citation2017). In the current research, we observe an extension of the physical state borders into the virtual global flows. This reflection is strongly rooted in the idea of uncertainty as a defining condition for patterns of globalization. Uncertainty forces global APS firms to divide their operations in each country and withdraw their strategic presence from the region. Consequently, despite the significant growth of the network size, the efficiency of connections between capital cities does not increase, and Moscow does not perform efficiently despite being the most connected node.

Globalization patterns in the FSU are notably shaped by patterns of Soviet central planning and its demolition. A low density of cities and the supremacy of top-down decision-making in the states support dominant positions of capital cities within the network. But inequality between and within the states, and a concentration of wealth in the largest cities (Zubarevich Citation2012), limit the sprawl of the networks and the intensity of connections between cores and peripheries. Consequently, the efficiency of capitals as central nodes decreases. Illusory control over space reinforces intraregional conflicts, in which disputed territories become symbolic gains, possessed by politicians (O’Loughlin and Toal Citation2019; Yacoubian and George Citation2022). Conflicts ruin the interaction between states and decrease the strategic significance of the region as a whole for global businesses. As a result, global isolation is partly reproduced through external market mechanisms.

Globalization within the FSU – which some scholars consider to be a decolonizing power and a way to overcome the Soviet heritage (Alexander Etkind Citation2022; Petsinis Citation2019) – has proven to be determined by the Soviet past. Global APS firms, which are expected to provide conditions for doing business worldwide, are strongly impacted in their localization by the effects of the Soviet heritage and the dissolution of the USSR. Generally speaking, in the FSU the global is shaped by the local rather than the opposite. The high level of uncertainty serves as an argument for this. In a risky environment, companies are less likely to invest in interstate networks and strategic offices. The fragmentation of the space is observed in the region through the lens of the corporate structures of APS firms. Considering the increasing localization of corporate networks within the state borders, we can also assume that the space fragmentation is strengthened by the global actors adjusting their business strategies to uncertainty.

Conclusion

The illusion of a relatively peaceful dissolution of the USSR was constructed during the 1990s (Tolz Citation1998) following the idea of neoliberal transformation (Golubchikov, Badyina, and Makhrova Citation2014). Discussion devoted to post-socialism questioned the term itself, claiming that since the collapse of the USSR was over, socialism had become the “zombie” of the scientific discourse (Chelcea and Druţǎ Citation2016). In this paper, we argue that the dissolution of the USSR is an ongoing process rather than an accomplished fact. Consequently, FSU is a space of high uncertainty. Being intertwined with the traumatic past, they are trying to redeem, reconsider, recycle, or refuse their connection to the Soviet legacy (Alexander Etkind Citation2022; Gerlach and Kinossian Citation2016). The introduction of uncertainty as a term offers an opportunity to study the space in a flexible way, taking the past into account but not being oppressed by it. We believe that understanding uncertainty as a harsh and continuous but reducible condition can be productive for any instable and insecure region of the world, widening the postcolonial lens of regional studies.

The localization of the global APS companies, driven by market logics, highlights the intricate character of the space and depicts the process of its dissolution. Addressing structures of the global APS companies through the lens of the WCN approach makes it possible to observe how the regional pattern of uncertainty grasps the trend of globalization. The networks of the global APS companies in the FSU are not just fragmenting; they are fragmenting quickly and in a disorderly way, following the current milieu of political, social, and economic conditions. Space fragmentation differs from the other trends reported from the network analysis, being the only sustainable trend described. The considerable lack of overconnection between capital cities, the improving connectivity between cities of the same country, the decreasing average node connectivity, and Moscow featuring as a strongly underconnected node are the attributes of the continued uncertainty within the post-Soviet region.

In the research we assume that global APS companies follow the logics of the market and their corporate strategies when making decisions about the location of their offices. But when the market is unpredictable, and the local actors are accustomed to this unpredictability, global companies have to provide coping strategies and adjust their decision-making to the regional specificity. Constructing a more complex network of subsidiaries, splitting the businesses into different countries, and focusing on precise subregions are among such strategies. An unpredictability of the space forces companies to make swift decisions, creating the chaotic dynamics within the networks. And when this dynamic is observed, it depicts uncertainty. We believe it would be fruitful for future research to apply the same data collection method to a developed country or group of countries and verify whether the networks of APS companies are sustainable there. Meanwhile, the studies of world cities by Peter J. Taylor and coauthors depict sustainable structures of networks in the Global North (Taylor Citation2001, Citation2013; Taylor and Derudder Citation2015; Taylor et al. Citation2014; Taylor, Derudder, and Liu Citation2021).

Despite strong claims about globalization being a universal condition, some regions, such as parts of the FSU, are growing less and less connected, bypassed by the global flows of information represented by the APS firms. In the current research, we were able to track the uncertainty using the modeling of quasi-random networks. The employment of open data and modeling provides a body of unified data, available for all the countries of the region despite diverse approaches to the collection and publication of the local statistical data. This is specifically significant for the uncertain regions, which typically lack assets for collecting precise data or have politically driven reasons not to publish it.

Indeed, relying on open corporate data limits research into the service occupation: Industrial and extraction companies are less likely to share the current locations of their offices and plants. Furthermore, the shift from flows of information between offices to flows of information between cities may be questionable. However, the perception of global service companies as brokers, empowering the spread of globalization worldwide (Baldwin Citation2016; Dicken Citation2007; Taylor Citation2001), makes studying them relevant in the broad context of the inclusion of the regional scope in the global. The research is based on the critical role global APS companies play in spreading globalization and providing unique and unified conditions for global businesses worldwide. All things considered, this assumption is highly questionable. If global APS companies reflect the uncertainty rather than overcome it, their role as the brokers of globalization should be reconsidered and studied in detail. Future research, in our opinion, should focus on revealing how global companies operate within the space compared to local actors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. Our interdisciplinary team has studied post-socialist cities over a long period of time. We marvel at the unique character of our research object and hope that the uncertainty and violence in the former USSR will not be endless. We quite literally reflect the intricate connections in post-Soviet space. Artem was born in Kazakhstan, Oleksandra is Ukrainian, Maria P. is half Russian and half Armenian, and Maria G. is partly Ukrainian and partly Russian. Wars and violence in the post-Soviet space deeply shock and devastate us.

References

- Aghion, Philippe, and Simon Commander. 1999. “On the Dynamics of Inequality in the Transition.” The Economics of Transition 7 (2): 275–298. doi:10.1111/1468-0351.00015.

- Agnew, John A. 2012. “Arguing with Regions.” Regional Studies 47 (1): 6–17. doi:10.1080/00343404.2012.676738.

- Ahsan, Mujtaba, and Martina Musteen. 2011. “Multinational Enterprises’ Entry Mode Strategies and Uncertainty: A Review and Extension.” International Journal of Management Reviews 13 (4): 376–392. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2370.2010.00296.x.

- Allen, John. 2003. Lost Geographies of Power. London: Blackwell. doi:10.1002/9780470773321.

- Amin, Ash. 2011. “Urban Planning in an Uncertain World.” In The New Blackwell Companion to the City, edited by Gary Bridge and Sophie Watson, 631–643. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. doi:10.1002/9781444395105.ch55.

- Antoine, Sebastien, Cecile Sillig, and Hilda Ghiara. 2016. “Advanced Logistics in Italy: A City Network Analysis.” Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie 108 (6): 753–767. doi:10.1111/tesg.12215.

- Arkhipova, Aleksandra, and Anna Kirziuk. 2020. Opasnye Sovetskie Veschi: Gorodskie Legendy i Strakhi v SSSR [Dangerous Soviet Things: Urban Legends and Fears in USSR]. Moscow: Novoe Literaturnoe Obozrenie.

- Baldwin, Richard. 2016. The Great Convergence: Information Technology and New Globalization. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Barabási, Albert-László. 2010. Bursts: The Hidden Patterns Behind Everything We Do, from Your E-Mail to Bloody Crusades. New York: Penguin.

- Batunova, Elena, and Maria Gunko. 2018. “Urban Shrinkage: An Unspoken Challenge of Spatial Planning in Russian Small and Medium-Sized Cities.” European Planning Studies 26 (8): 1580–1597. doi:10.1080/09654313.2018.1484891.

- Beacháin, Donnacha Ó., and Abel Polese, eds. 2010. The Colour Revolutions in the Former Soviet Republics: Successes and Failures. 1st ed. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203848951.

- Beck, Ulrich. 2016. The Metamorphosis of the World: How Climate Change is Transforming Our Concept of the World. Malden, MA: Polity Press.

- Ben, Derudder, and Peter J. Taylor. 2018. “Central Flow Theory: Comparative Connectivities in the World-City Network.” Regional Studies 52 (8): 1029–1040. doi:10.1080/00343404.2017.1330538.

- Ben, Derudder, and Peter J. Taylor. 2020. “Three Globalizations Shaping the Twenty-First Century: Understanding the New World Geography Through Its Cities.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 110 (6): 1831–1854. doi:10.1080/24694452.2020.1727308.

- Blondel, Vincent D., Jean-Loup Guillaume, Renaud Lambiotte, and Etienne Lefebvre. 2008. “Fast Unfolding of Communities in Large Networks.” Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory & Experiment, no. 10: 10008. doi:10.1088/1742-5468/2008/10/P10008.

- Brenner, Neil, and Christian Schmid. 2015. “Towards the New Epistemology of the Urban?” City 19 (2–3): 151–182. doi:10.1080/13604813.2015.1014712.

- Carmignani, Fabrizio. 2003. “Political Instability, Uncertainty and Economics.” Journal of Economic Surveys 17 (1): 1–54. doi:10.1111/1467-6419.00187.

- Castells, Manuel. 1997. “An Introduction to the Information Age.” City 2 (7): 6–16. doi:10.1080/13604819708900050.

- Castells, Manuel. 2020. “Space of Flows, Space of Places: Materials for a Theory of Urbanism in the Information Age.” In The City Reader, 7th edited by, Richard T. Le Gates, and Frederic Stout, 240–251. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780429261732-30

- Ceglowski, Janet. 2000. “Has Globalization Created a Borderless World?” In Globalization and the Challenges, edited by Patrick O’Meara, Howard D. Mehlinger Matthew Krain, and Roxana Ma Newman, 101–112. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt2005tk7.13.

- Chelcea, Liviu, and Oana Druţǎ. 2016. “Zombie Socialism and the Rise of Neoliberalism in Post-Socialist Central and Eastern Europe.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 57 (4–5): 521–544. doi:10.1080/15387216.2016.1266273.

- Chen, Rou-Lan. 2020. “Trends in Economic Inequality and Its Impact on Chinese Nationalism.” Journal of Contemporary China 29 (121): 75–91. doi:10.1080/10670564.2019.1621531.

- Clapham, Christopher. 2002. “The Challenge to the State in a Globalized World.” Development & Change 33 (5): 775–795. doi:10.1111/1467-7660.t01-1-00248.

- Coe, Neil M., and Henry Wai-Chung Yeung. 2015. Global Production Networks: Theorizing Economic Development in an Interconnected World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198703907.001.0001.

- Davidson, Paul. 1988. “A Technical Definition of Uncertainty and the Long-Run Non-Neutrality of Money.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 12 (3): 329–337.

- Derudder, Ben, Lomme Devrient, and Frank Witlox. 2007. “An Empirical Analysis of Former Soviet Cities in Transnational Airline Networks.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 48 (1): 95–110. doi:10.2747/1538-7216.48.1.95.

- Derudder, Ben, and Frank Witlox. 2008. “Mapping World City Networks Through Airline Flows: Context, Relevance, and Problems.” Journal of Transport Geography 16 (5): 305–312. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2007.12.005.

- Dicken, Peter. 2007. Global Shift: Mapping the Changing Contours of the World Economy. London: SAGE.

- Dicken, Peter, Philip F. Kelly, Kris Olds, and Henry Wai-Chung Yeung. 2001. “Chains and Networks, Territories and Scales: Towards a Relational Framework for Analysing the Global Economy.” Global Networks 1 (2): 89–112. doi:10.1111/1471-0374.00007.

- Di Clemente, Riccardo, Balázs Lengyel, Lars F. Andersson, and Rikard Eriksson. 2022. “Understanding European Integration with Bipartite Networks of Comparative Advantage.” PNAS Nexus 1 (5): 1–10. doi:10.1093/pnasnexus/pgac262.

- DiFonzo, Nicholas, and Bordia. Prashant. 2011. “Rumors Influence: Toward a Dynamic Social Impact Theory of Rumor.” In The Science of Social Influence, edited by Anthony R. Pratkanis, 271–295. New York: Psychology Press. doi:10.4324/9780203818565-11.

- Etkind, Alexander. 2022. Vnutrennyaya Kolonizatsiya: Imperskiy Opyt Rossii [Internal Colonization: Russian Imperial Experience]. Moscow: Novoe Literaturnoe Obozrenie.

- Etkind, Simon Noah, Katherine Bristowe, Katharine Bailey, Lucy Ellen Selman, and Fliss EM Murtagh. 2017. “How Does Uncertainty Shape Patient Experience in Advanced Illness? A Secondary Analysis of Qualitative Data.” Palliative Medicine 31 (2): 171–180. doi:10.1177/0269216316647610.

- Fauve, Adrien. 2015. “Global Astana: Nation Branding as a Legitimization Tool for Authoritarian Regimes.” Central Asian Survey 34 (1): 110–124. doi:10.1080/02634937.2015.1016799.

- Friedman, Thomas L. 2005. The World is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-First Century. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Frost, Irina. 2018. “Exploring Varieties of (Post)soviet Urbanization: Reconciling the General and Particular in Post-Socialist Urban Studies.” Europa Regional 25 , no. 2: 2–14.

- Frost, Irina, and Maria Podkorytova. 2018. “Former Soviet Cities in Globalization: An Intraregional Perspective on Interurban Relations Through Networks of Global Service Firms.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 59 (1): 98–125. doi:10.1080/15387216.2018.1506995.

- Fukuyama, Francis. 2006. The End of History and the Last Man. London: Free Press.

- Gao, Jian, Yi-Cheng Zhang, and Tao Zhou. 2019. “Computational Socioeconomics.” Physics Reports, no. 817: 1–104. doi:10.1016/j.physrep.2019.05.002.

- Gerlach, Julia, and Nadir Kinossian. 2016. “Cultural Landscape of the Arctic: ‘Recycling’ of Soviet Imagery in the Russian Settlement of Barentsburg, Svalbard (Norway).” Polar Geography 39 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1080/1088937X.2016.1151959.

- Golubchikov, Oleg. 2017. “The Post-Socialist City: Insights from the Spaces of Radical Societal Change.” In A Research Agenda for Cities, edited by John Rennie Short, 266–281. Cheltenham, MA: Edward Elgar. doi:10.4337/9781785363429.00030.

- Golubchikov, Oleg, Anna Badyina, and Alla Makhrova. 2014. “The Hybrid Spatialities of Transition: Capitalism, Legacy and Uneven Urban Economic Restructuring.” Urban Studies 51 (4): 617–633. doi:10.1177/0042098013493022.

- Goode, J., David Paul, and R. Stroup. 2022. “Everyday Nationalism in Unsettled Times: In Search of Normality During Pandemic.” Nationalities Papers 50 (1): 61–85. doi:10.1017/nps.2020.40.

- Gosudarstvennyy Komitet SSSR po Statistike [State Committee of Statistics of the USSR]. 1990. SSSR V Tsyfrakh V 1989 Godu (Kratkiy Statisticheskiy Sbornik). Moscow: Finansy i Statistika. [USSR in Numbers in 1989 (Brief Statistical Digest). http://istmat.info/node/19967.

- Guillermo, O’Donnell, and Philippe C. Schmitter. 2013. Transitions from Authoritarian Rule: Tentative Conclusions About Uncertain Democracies. Baltimore: JHU Press.

- Gurkov, Igor B. 2020. “Location of Russian Enterprises of Foreign Corporations Opened in 2012–2018.” Regional Research of Russia 10 (1): 29–37. doi:10.1134/S2079970520010049.

- Hanssens, Heidi, Ben Derudder, and Frank Witlox. 2013. “Are Advanced Producer Services Connectors for Regional Economies? An Exploration of the Geographies of Advanced Producer Service Procurement in Belgium.” Geoforum, no. 47: 12–21. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.02.004.

- Hirt, Sonia, Slavomira Ferencuhova, and Tauri Tuvikene. 2016. “Conceptual Forum: The ‘Post-Socialist’ City.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 57 (4–5): 497–520. doi:10.1080/15387216.2016.1271345.

- Holland, Edward C., and Matthew Derrick. 2016. “Introduction.” In Questioning Post-Soviet, edited by Edward C. Holland and Matthew Derrick, 5–19. Washington, DC: Wilson Center.

- Hoyler, Michael. 2011. “External Relations of German Cities Through Intra-Firm Networks - a Global Perspective.” Raumforschung und Raumordnung 69 (3): 147–159. doi:10.1007/s13147-011-0100-8.

- Jacobs, Wouter, Hans Koster, and Peter Hall. 2011. “The Location and Global Network Structure of Maritime Advanced Producer Services.” Urban Studies 48 (13): 2749–2769. doi:10.1177/0042098010391294.

- Jimu, Ignasio Malizani. 2016. Moving in Circles: Underdevelopment and the Narrative of Uncertainty in the Global Periphery. Mankon: Langaa RPCIG.

- Jost, John T. 2017. “Ideological Asymmetries and the Essence of Political Psychology.” Political Psychology 38 (2): 167–208. doi:10.1111/pops.12407.

- Kabiraj, Tarun, and Mukherjee. Arijit. 2019. “International Joint Ventures in Developing Countries: The Implications of Policy Uncertainty and Information Asymmetry.” In Opportunities and Challenges in Development. Essays for Sarmila Banerjee, edited by Simanti Bandyopadhyay and Mousumi Dutta, 331–355. Singapore: Springer Nature. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-9981-7_15.

- Kenyon, Thomas, and Megumi Naoi. 2010. “Policy Uncertainty in Hybrid Regimes: Evidence from Firm-Level Surveys.” Comparative Political Studies 43 (4): 486–510. doi:10.1177/0010414009355267.

- Knox, Hannah, Mike Savage, and Penny Harvey. 2006. “Social Networks and the Study of Relations: Networks as Method, Metaphor and Form.” Economy and Society 35 (1): 113–140. doi:10.1080/03085140500465899.

- Kobrin, Stephen J. 2001. “Soverignity@bay: Globalization, Multinational Enterprise and the International Political System.” In Oxford Handbook of International Business, edited by Alan M. Rugman, 181–205. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/0199241821.003.0007.

- Kobrin, Stephen J. 2017. “Bricks and Mortar in a Borderless World: Globalization, the Backlash, and the Multinational Enterprise.” Global Strategy Journal 7 (2): 159–171. doi:10.1002/gsj.1158.

- Kuhn, Manfred. 2015. “Peripheralization: Theoretical Concepts Explaining Socio-Spatial Inequalities.” European Planning Studies 23 (2): 367–378. doi:10.1080/09654313.2013.862518.

- Kuzio, Taras. 2001. “Transition in Post-Communist States: Triple or Quadruple?” Politics 21 (3): 168–177. doi:10.1111/1467-9256.00148.

- Liu, Linqing, Mengyun Shen, Da Sun, Xiaofei Yan, and Hu. Shi. 2022. “Preferential Attachment, R&D Expenditure and the Evolution of International Trade Networks from the Perspective of Complex Networks.” Physica A Statistical Mechanics & Its Applications 603: 127579. doi:10.1016/j.physa.2022.127579.

- Liu, Linqing, Mengyun Shen, and Chang Tan. 2021. “Scale Free is Not Rare in International Trade Networks.” Scientific Reports 11 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-92764-1.

- Loginova, Julia, Thomas Sigler, Kirsten Martinus, and Matthew Tonts. 2020. “Spatial Differentiation of Variegated Capitalisms: A Comparative Analysis of Russian and Australian Oil and Gas Corporate City Networks.” Economic Geography 96 (5): 422–448. doi:10.1080/00130095.2020.1833713.

- Loginova, Julia, Thomas Sigler, Glen Searle, and Kevin O’Connor. 2022. “The Distribution of National Urban Hierarchies of Connectivity within Global City Networks.” Global Networks 22 (2): 274–291. doi:10.1111/glob.12344.

- Lupu, Noam, and Rachel Beatty Readl. 2012. “Political Parties and Uncertainty in Developing Democracies.” Comparative Political Studies 46 (11): 1339–1365. doi:10.1177/0010414012453445.

- Luthi, Stefan, Alain Thierstein, and Michael Hoyler. 2018. “The World City Network: Evaluating Top-Down versus Bottom-Up Approaches.” Cities, no. 72: 287–294. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2017.09.006.

- Mainwaring, Scott, and Edurne Zoco. 2007. “Political Sequences and the Stabilization of Interparty Competition: Electoral Volatility in Old and New Democracies.” Party Politics 13 (2): 155–178. doi:10.1177/1354068807073852.

- Massey, Doreen. 2007. World City. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Mazzucato, Mariana, and Rosie Collington. 2023. The Big Con. How the Consulting Industry Weakens Our Businesses, Infantilizes Our Governments and Warps Our Economies. Milton Keynes: Allen Lane.

- McEwan, Cheryl 2019 Postcolonialism, Decoloniality and Development 2 (London: Routledge)

- Muller, Martin, and Elena Trubina. 2020a. “The Global Easts in Global Urbanism: Views from Beyond North and South.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 61 (6): 627–635. doi:10.1080/15387216.2020.1777443.

- Muller, Martin, and Elena Trubina. 2020b. “Improvising Urban Spaces, Inhabiting the In-Between.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 38 (4): 1–19. doi:10.1177/0263775820922235.

- Neal, Zachary P. 2017. “Well Connected Compared to What? Rethinking Frames of Reference in World City Network Research.” Environment & Planning A 49 (12): 2859–2877. doi:10.1177/0308518X16631339.

- Neal, Zachary P. 2018. “Is the Urban World Small? The Evidence for Small World Structure in Urban Networks.” Networks and Spatial Economics 18 (3): 615–631. doi:10.1007/s11067-018-9417-y.

- Neal, Zachary P., Rachel Domagalski, and Bruce Sagan. 2022. “Analysis of Spatial Networks from Bipartite Projections Using the R Backbone Package.” Geographical Analysis 54 (3): 623–647. doi:10.1111/gean.12275.

- Nefedova, Tatyana, and Andrei Treivish. 2003. “Differential Urbanisation in Russia.” Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie 94 (1): 75–88. doi:10.1111/1467-9663.00238.

- O’Dowd, Liam. 2010. “From a ‘Borderless World’ to a ‘World of Borders’: ‘Bringing History Back in’.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 28 (6): 1031–1050. doi:10.1068/d2009.

- Ohmae, Kenichi. 1990. The Borderless World: Power and Strategy in the Interlinked Economy. New York: Harper Business.

- Ohmae, Kenichi. 2000. The Invisible Continent: Global Strategy in the New Economy. New York: Harper Business.

- O’Loughlin, John, and Gerard Toal. 2019. “The Crimea Conundrum: Legitimacy and Public Opinion After Annexation.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 60 (1): 6–27. doi:10.1080/15387216.2019.1593873.

- Osokina, Elena. 2008. Za Fasadom ”Stalinskogo Izobiliia”: Raspredelenie i Rynok v Snabzhenii Naseleniia v Gody Industrializatsii, 1927-1941[Behind the Facade of “Stalinist Abundance”: Distribution and Market in Supplying the Population During the Years of Industrialization, 1927-1941]. Moscow: ROSSPEN.

- Paasi, Anssi. 2019. “Borderless Worlds and Beyond: Challenging the State-Centric Cartographies.” In Borderless Worlds for Whom? Ethics, Moralities and Mobilities, edited by Anssi Paasi, Eeva-Kaisa Prokkola, Jarkko Saarinen, and Kaj Zimmerbauer, 2–16. Abingdon: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780429427817.

- Pan, Fenghua, Bi Wenkai, James Lenzer, and Simon Zhao. 2017. “Mapping Urban Networks Through Inter-Firm Service Relationships: The Case of China.” Urban Studies 54 (16): 3639–3654. doi:10.1177/0042098016685511.

- Peck, Jamie, and Nik Theodore. 2007. “Variegated Capitalism.” Progress in Human Geography 31 (6): 731–772. doi:10.1177/0309132507083505.

- Pervushina, Elena. 2012. Leningradskaia Utopiia: Avangard v Arkhitekture Severnoy Stolitsy [Leningrad Utopia: Avant-Garde in the Architecture of the Northern Capital]. Moscow: Tsentrpoligraf.

- Petsinis, Vassilis. 2019. “Identity Politics and Right-Wing Populism in Estonia: The Case of EKRE.” Nationalism & Ethnic Politics 25 (2): 211–230. doi:10.1080/13537113.2019.1602374.

- Polanyi, Karl. 1945. “Universal Capitalism or Regional Planning?” The London Quarterly of World Affairs 10 (3): 86–91.

- Rantanen, Terhi. 2005. “The Message is the Medium: An Interview with Manuel Castells.” Global Media and Communication 1 (2): 135–147. doi:10.1177/1742766505054629.

- Redl, Chris. 2018. “Macroeconomic Uncertainty in South Africa.” South African Journal of Economics 86 (3): 361–380. doi:10.1111/saje.12198.

- Robinson, Jennifer. 2002. “Global and World Cities: A View from off the Map.” International Journal of Urban & Regional Research 26 (3): 531–554. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.00397.

- Rogov, Mikhail, and Celine Rozenblat. 2022. “Intercity Economic Networks Under Recession: Counterintuitive Results on the Evolution of Russian Cities in Multinational Firm Networks from 2010 to 2019.” Journal of Urban Affairs 1–29. doi:10.1080/07352166.2022.2041987.

- Roy, Ananya. 2009. “The 21st-Century Metropolis: New Geographies of Theory.” Regional Studies 43 (6): 819–830. doi:10.1080/00343400701809665.

- Sassen, Saskia. 1991. The Global City. New York, London, Tokyo. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Sassen, Saskia. 2005. “The Global City: Introducing a Concept.” The Brown Journal of World Affairs 11 (2): 27–43.

- Saxer, Martin, and Ruben Andersson. 2019. “The Return of Remoteness: Insecurity, Isolation and Connectivity in the New World Disorder.” Social Anthropology 27 (2): 140–155. doi:10.1111/1469-8676.12652.

- Serrano, Ma Angeles, and Marián Boguná. 2003. “Topology of the World Trade Web.” Physical Review E 68 (1): 015101. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.68.015101.