ABSTRACT

Over the past three decades, rural places along China’s land borders have faced interconnected processes of socio-political, economic, and ecological change. These changes, along with an increase in transboundary investment by actors from China in infrastructure on the one hand, and in agriculture and resource extraction on the other, are locally met with a combination of suspicion, fear, and desire for future prosperity. This special issue scrutinizes these dynamics in extractive sectors, particularly agriculture, the plantation industry, and mining, in the context of transboundary processes that can be conceptualized as “neighboring”. With an array of qualitative and ethnographic methods and case studies from borderlands in North, Central, South and Southeast Asia that are rarely thought of together, the six articles of this special issue provide a unique perspective on “China’s rise” in Asia that goes beyond schematical geopolitical and macro-economic accounts of the ‘Belt and Road Initiative.‘ This introduction to the special issue discusses the key insights and arguments it brings forward and calls for (a) more comparative research on transboundary natural resource use in China’s neighborhood and (b) more holistic and multi-scalar research perspectives to make sense of the complex dynamics on the ground.

Introduction

The warm autumn sun was disappearing behind the snowy mountain ranges of Zhungar Alatau and attached long shadows to the two gigantic grain elevators on the outskirts of the rural town of Sarkan in Southeastern Kazakhstan. As soybean had re-appeared in that region on the Kazakhstan-China border as a promising and highly profitable cash crop in the 2010s, most smallholders and many larger farmers had shifted toward its cultivation, side-lining sugar beet as the dominant crop in the area. Vast soybean monocultures and relatively stable annual harvests had attracted the construction of domestic soybean storage and processing facilities, particularly for the production of animal feed. Foreign investors, particularly from China next door, also entered the scene to benefit from the commodification of local farmers’ soybean resources and the competitive wholesale prices on this side of the border. The high metal fences around the grain elevators, shielding them from curious glimpses, elucidated the secretive character of Chinese business activities in transborder agricultural production and trade or more generally in natural resource exploration. Only hesitantly did the gatekeeper of the otherwise deserted elevator complex, a Kazakh of Chinese origin, provide information on the proprietors of the object, Chinese business people with good connections to regional-level state officials in Kazakhstan. He however pointed out that the enduring closure of the border since the start of the global COVID-19 pandemic and the lack of adequate local transport infrastructure somewhat questioned the economic feasibility of the elevators, each with a storage capacity of 12,000 tons.

This situation as observed by one of the authors in fall 2021 illustrates the nontransparent and sometimes seemingly contradictory nature of Chinese investments in neighboring countries that have officially been declared as partners of the so-called Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) since 2013. Through the BRI, Chinese actors have played a critical and very visible role in the revitalization of road and rail construction and improvement across Asia over the past decade (Woodworth and Joniak-Lüthi Citation2020). Much public and scholarly attention has been given to these infrastructure projects on roads and railways and other BRI-related infrastructure such as dry ports and special economic zones in border regions of China (Garlick Citation2018; Joniak-Lüthi Citation2016; Murton and Lord Citation2020; Rippa Citation2020b). These projects have been found to create and support, but also often disrupt, visions of economic opportunities and often fail to generate win-win situations between foreign investors and rural populations.

This special issue highlights a less commonly researched but no less important sector: initiatives by Chinese actors in food, agriculture and natural resource extraction in its Asian neighborhood. Such initiatives have variously been related to the BRI (Tortajada and Zhang Citation2021) and to China’s policies of “Going Out” and “Good Neighbor” (Liao Citation2019), while increasingly being framed as “greening” efforts in official state discourse (CCICED Citation2019; Ho Citation2006; Yeh Citation2009, Citation2013). Apart from geopolitics, scholars have also highlighted strategies to secure the increasing demand for agricultural and other natural resources for China’s growing economy (Wesz Junior, Escher, and Fares Citation2021). While much has been written about driving forces, questions remain concerning the social-ecological implications of state and corporate interventions on rural places and people in the borderlands, also demonstrating considerable power imbalances between the involved actors. Earlier Chinese interventions into resource exploitation (including what has often been termed as land- (and ocean-) grabbing in other parts of the world) and the increasing demand for commodities such as oil, jade, timber, cotton or rare animal products have led to the overuse of natural resources along with ecosystem degradation and substantial changes in livelihood systems (Jackson and Dear Citation2016; Nyíri and Breidenbach Citation2008; Rippa and Yang Citation2017).

The contributions to this special issue scrutinize recent and ongoing developments related to natural resource use close to China’s land borders, and investigate how they are affected or implicated by transboundary dynamics of trade and investment, infrastructural “improvement”, the Chinese presence and related discourses, and power relations, among other factors. The articles take, first and foremost, an empirically grounded and case study-based perspective, providing new and original insights from remote borderlands, several of which have received very little attention by geographers so far. Moreover, the complexity of local developments requires a holistic perspective that regards Chinese interventions in the context of several other co-occurring, often interrelated processes of change. As several contributions highlight, Chinese initiatives in the natural resource sector are often prominently driven by Beijing in official policy visions of development, but when closely examined at the local level, they often materialize to a rather limited degree or in unexpected ways. Another important point throughout this special issue is the fact that Chinese actors are not necessarily the most influential ones in the dynamics observed, among others due to strict regulations of respective state authorities, their sheer physical absence, or the dominance of other actors. Inspired by research approaches like assemblage (Spies Citation2023) and actor-network theory (Ryzhova and Ivanov Citation2023) and critical socio-spatial concepts such as “ruination” (Ahearn and Sternberg Citation2023) and “plantation” (Sarma, Rippa, and Dean Citation2023), the contributions explore and conceptualize the multi-scalar social negotiations between different (human and non-human) actors (state officials, enterprises, (trans-) border groups, various local land users, technical infrastructures among others) in shaping present and future rural transformations in China’s neighborhood. Given the decreasing availability of and increasing competition for resources (agricultural commodities, mineral resources among others), this special issue brings together insights from diverse geographical settings to sketch out the complexity of local trajectories and the closely interrelated roles of Chinese and other actors therein.

Geographical and topical scope

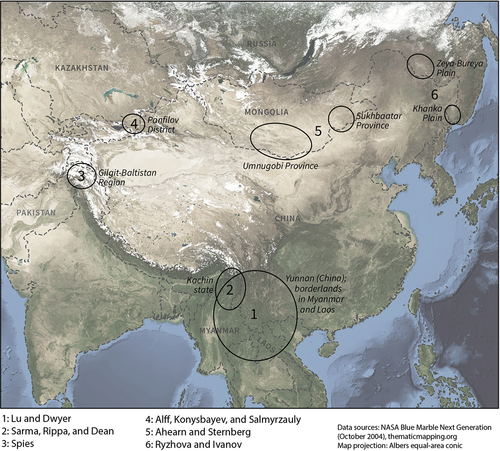

This special issue brings together case studies from places that have seldom been thought of together due to their geographical, political and socio-cultural differences: China’s borderlands in Central, North, Southeast and South Asia (). Despite their differences, they share some intriguing similarities. First, conceptualized as China‘s “borderlands”, these places are sites of historically (in imperial and colonial contexts) sedimented practices of social inter- and transaction between different sets of actors, be it (il)licit trade, migration or mobility and including negotiations about resource extraction and commodification. Due to the particularities of China’s history, many of the borders until the mid-20th century existed as zones (rather than territorial lines or planes) and only more recently have been demarcated and consolidated, which sets them in contrast to the local population’s often rather arbitrary sense-making. We hence acknowledge the specific role of these Asian borderlands, in which (state, ethnic communities and other actors‘) interests meet each other, often at the same time (and in complex ways) overlap, conflict and (re-) align (Van Schendel and de Maaker Citation2014).

Second, over the past three decades, many rural places along China’s land borders have faced cataclysmic and largely interconnected processes of socio-political, economic, and ecological change. In the post-Soviet (and post-Socialist) states bordering China, for instance, the dismantling of collective and state farms since 1991 has led to deterioration of infrastructure and low performance among emerging smallholder farmers concerning sustainable resource management. An increase in rural precariousness overlapped with and facilitated the political marginalization of village communities, and rural households often shifted their livelihood strategies toward the off-farm sector, with petty trade, outmigration, and construction and transportation services playing an important role as means of income generation (Alff Citation2016a; Dörre Citation2014; Parham Citation2017). At the same time, similar livelihood shifts have been evident in the mountain regions of South and Southeast Asia bordering China: through transborder infrastructural developments and political-economic integration, an increased mobility of people, goods, and ideas has affected the formerly remote mountain communities in manifold ways (Karrar Citation2021; Lu Citation2017; Spies Citation2018). In Northern Asia, too, the post-Socialist decline affected particularly remote border zones, which shifted livelihood priorities and fostered many people to leave for employment and income generation. At the same time, there has been a rapidly increasing demand for natural resources from mining, forestry, and animal husbandry, and the upgrade of (transport) infrastructures put pressure on vulnerable social and environmental systems in the region.

These changes have to be scrutinized also considering the various development processes and visions since the beginning of the reform era under Deng Xiaoping in the early 1980s, which led to an opening of China’s economy. Since that time, China’s border regions in the South, West, and North of the country, which are often inhabited by similar ethno-linguistic groups as across the border (Alff Citation2016b; Grant Citation2020; Rippa Citation2020b), have been subject to far-reaching transformations. As these processes and visions increasingly follow an outward-looking perspective, many experts would agree that investments across the border for a large part reflect political strategies to trigger domestic economic development in China’s Western regions (Rippa Citation2020b, Citation2020a; Woodworth and Joniak-Lüthi Citation2020). The language of “bridgeheads” in relation particularly to the (South-) Western border regions in the official discourse demonstrates this intention of the Chinese leadership under Xi Jinping (Summers Citation2016, Citation2019). However, borderlands not only provide analytical lenses to scrutinize the impact of Chinese official economic policies in the margins of states. In fact, borderlands in general serve as rather complex arenas or critical junctions to observe patterns of persistence (or even resistance) and socio-economic and -political change at the same time. The concept of neighboring, coined by Saxer and Zhang (Citation2016), provides a notion to make sense of the ambivalent and unpredictable, localized social, socioeconomic and political processes overlapping in China’s borderlands. “Neighboring” according to Saxer and Zhang (Citation2016, 15) refers to geographically fixed, but also often surprisingly fluid, encounters of actors at border crossings, in border zones and in market places. Neighboring, however, can occur also removed from borders and “still remain functionally linked to particular opportunities and risks presented by [border] locations” in China and across the border from there (Saxer and Zhang Citation2016, 15). “Closeness” or “proximity”, in Zhang’s and Saxer’s opinion, cannot be measured in kilometers or miles. Rather, “neighboring” as a set of social interactions refers to a condition or a state of connectedness with others, with certain socio-political consequences for those being connected (Saxer and Zhang Citation2016, 15). Thus, as some contributions to this special issue show, understanding Chinese actors’ engagements with other “borderlanders” in neighboring countries requires taking a close look at the complex developments near, but sometimes also far beyond, the border. In the case of China, this means that central state policies obviously matter for what is happening in its borderlands, but also that China’s borderlands provide a space from which to view the center with more clarity (Oakes Citation2012). However, as Lu and Dwyer (Citation2023) and Spies point out in their respective contributions to this special issue, actors and processes in China’s border regions play also a critical role in shaping development trajectories in the areas across the border.

In the border regions scrutinized in this special issue, recent years have generated a massive influx of investment by various stakeholders from China into transboundary infrastructures on the one hand (Heslop and Murton Citation2021; Joniak-Lüthi Citation2020) but also into agriculture and resource extraction (mining and (agro-) forestry) in the regions across the border (Dong and Jun Citation2018; Hofman Citation2022; Toktomushev Citation2021). These overall processes and individual projects are often put under the label of win-win development, people-to-people exchanges, and transborder harmonization (Lin, Shimazu, and Sidaway Citation2021; Sidaway and Woon Citation2017). However, locally they are often met with a combination of suspicion, fear, and desire for future prosperity (Karrar Citation2022; Nyíri and Tan Citation2016; Saxer and Zhang Citation2016).

Zooming into different localities in Laos, Myanmar, Pakistan, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, and Russia (), the contributions to this special issue adopt various conceptual and methodological perspectives in their analysis of resource use and extraction in China’s borderlands and the role of Chinese actors therein. Taken together, they contribute to the international research community at the intersection of Asian borderlands studies (Woodworth and Joniak-Lüthi Citation2020), BRI research (Panibratov et al. Citation2022), and resource geographies (Bakker and Bridge Citation2006; Huber Citation2019) with fresh and original material to shed light on a number of critical questions. In what way and to what extent is natural resource use and extraction in these places shaped by Chinese presence and investments and how has this changed over time? What are the drivers of these developments and what are the consequences? How are these developments complicated by a multitude of other local and external actors and processes, which may even be more influential than Chinese actors? What are the particularities of the borderland context in these transformation processes, especially the changing role of border zones in the era of China’s rise? And how do communities perceive and engage with these developments and become involved in the dynamics of “neighboring”?

Articles in this special issue

In the first article of this special issue, Juliet Lu and Mike Dwyer focus on the Chinese side of the border to investigate the changing drivers and dynamics of Chinese agribusiness investments in Laos and Myanmar as part of the Opium Replacement Program (ORP), one of China’s first cross-border development programs in the region, over the last two decades. Drawing on public company-level data on agribusiness investments from Yunnan in the borderlands of “neighboring” regions of Laos and Myanmar, they reveal how regulatory activities of the ORP have shifted from an outward focus concerned with local impacts in the investment countries to a more inward focus dealing with the diverse (business) interests of Chinese actors, particularly in Yunnan. Their findings reveal the important role of borderland authorities and businesses in shaping the ORP’s implementation and outcomes by adapting, modifying, and challenging central-level directives of transborder development cooperation. Using the concept of vertical politics, Lu and Dwyer contribute to a growing literature that challenges the notions of China’s central power having full control of its going-out activities and paint a more nuanced picture of the complex “assemblage” of actors, institutions and interests shaping China’s cross-border agricultural investments.

Focusing on the same region of Southeast Asia but zooming into the borderland state of Kachin, Myanmar, Jasnea Sarma, Alessandro Rippa, and Karin Dean complement the previous article well by investigating the local consequences of Chinese transboundary agribusiness investments in banana and other plantations from an empirically grounded ethnographic perspective. Based on in-depth field research on both sides of the border, they explore the complex roles of plantations as both sites of contestation as well as the cause and consequence of far-reaching socio-political change. Taking a comprehensive perspective on the actors and processes involved, Sarma, Rippa, and Dean show how Chinese-funded plantations have (a) led to irreversible social-ecological transformations that (b) trap many local people into a cycle of dispossession, labor exploitation, and health and welfare risks, while (c) being shaped by and reshaping local power relations through collaboration with individual landholders and armed groups who appear to gradually lose control over this foreign presence for the sake of short-term economic gains. Local communities, in turn, are increasingly marginalized by this development, with some even perceiving plantations as a bigger threat than the ongoing civil war.

In his contribution about agriculture and export prospects in Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan, Michael Spies focuses on a border region with China that has been subject to much academic and media debate in relation to the BRI, as it is home to its flagship megaproject China-Pakistan-Economic Corridor (CPEC). In contrast to Myanmar and Laos, however, no publicly known agribusiness investments have materialized in this region despite big policy announcements about making agricultural development a priority sector of CPEC. Spies looks behind these policy announcements, scrutinizing in particular the promise of CPEC policy makers to boost the export of fresh cherries from Gilgit-Baltistan to satisfy a growing market in China. Drawing on interviews with traders, cherry farmers, and other actors in the region, he investigates the prospects and risks of cherry export by examining the interplay of CPEC and the complex farming assemblages in the region. He finds that policy negotiations between Pakistan and China and agricultural developments across the border in Xinjiang are among the key determinants for making this endeavor a success or failure for local cherry farmers.

Similar to Spies’ case, Henryk Alff, Talgarbay Konysbayev, and Ruslan Salmyrzauly highlight the promises as well as the realities of China’s impact on agricultural development with a focus on the agrarian border district of Panfilov in the Kazakhstan-China borderlands. Like Gilgit-Baltistan in the CPEC context, this section of the Chinese border has become a hotspot of massive infrastructural upgrades in the form of the Khorgos dry port, a transborder small-scale trade special economic zone with China, and transboundary transport schemes. Drawing on recent field research and taking a holistic and historically informed perspective, the authors investigate how the transformed border regimes since the early 1990s determine the permeability of the border for knowledge exchange, actor mobility, and the trade in agricultural commodities and assets. Looking particularly at local perceptions, Alff, Konysbayev, and Salmyrzauly (Citation2023) emphasize China’s often weak presence in the agricultural sector of the region. Yet, they also picture the persistent role of institutional path-dependencies still shaping many local people’s mind-sets and economic activities through the post-Soviet past and present, despite the oft-felt neglect by the local state administration.

Somewhat in contrast to the rather stagnant condition of the state in the Kazakhstan case, Ariell Ahearn and Troy Sternberg in their contribution on the Sino-Mongolian case put into the center of analysis the extensive negotiating power of the Mongolian government and of local communities in regulating the exploitation of the Gobi Desert’s mineral riches. At the same time, they scrutinize local conflicts arising from the over-extraction in and export of minerals from the borderlands, particularly at mining projects in Mongolia where Chinese investors have a stake. To scrutinize the complex intermingling of “contestations over land, territory and development”, Ahearn and Sternberg draw on extensive fieldwork and theoretically relate their investigation to the concept of “ruination” to better grasp the dynamics and consequences of mining in these localities. “Ruination” conceptually connects to other authors’ approaches to disruptive environmental (or landscape) change, especially to the plantation economy in Sarma, Rippa, and Dean’s case in Southeast Asia.

In another study from a post-Socialist setting, Natalia Ryzhova and Sergei Ivanov investigate what the “Chinese presence,” characterized by much more direct and personified contact than in Alff, Konybayev, and Salmyrzauly’s case, in the agricultural sector of the Russian Far East means in terms of capitalist and non-capitalist economic interrelations. The authors analyze how Chinese actors (farmers and agribusinesses) by way of their presence shape agricultural transformation in the region in multifaceted and often unexpected ways. In doing so, Ryzhova and Ivanov look at the complexity of Chinese and Russian actors and interests in local agriculture and how they have often co-evolved rather than being independent from each other. Thus, Ryzhova and Ivanov adopt rather explicitly the “neighboring” lens to scrutinize farming actors’ inter- and transactions. Similar to other authors in this issue, they show that both the presence and absence of Chinese actors have much to do with social embeddedness and simultaneously shape, through perceptions and imaginaries, the farming strategies of local actors and the post-Soviet institutional farming “landscapes” of the Russian Far East as a whole.

Conclusion

Bringing into relation multilevel aspects of natural resource use on and across China’s inland borders, particularly the local population’s position within and perceptions of resource extraction shaped by Chinese actors, this special issue reveals intriguing findings from the ground. The authors present nuanced actor-centered accounts of processes of natural resource use in China’s borderlands in North, Central, South, and Southeast Asia against the often overwhelmingly enthusiastic developmental rhetoric of BRI planning documents and leading politicians. A key argument brought forward by the contributions to this special issue is that Chinese initiatives in the natural resource sector are often heavily pushed forward by Beijing in official development policies, but become manifest to a rather limited degree or in unexpected ways when thoroughly looked at from the ground of borderlands. A second critical point made explicit in this collection of articles is the fact that Chinese actors often do not wield as much power in resource use dynamics in the borderlands of neighboring countries as popular perceptions and academic discourses sometimes suggest. Rather, they have to navigate through a difficult regulatory environment, negotiate compromises with influential state or non-state actors, and sometimes, they may not be present at all.

This special issue hence provides a critical, empirically based, and in some ways soberer assessment of Chinese resource extraction across inland Asia than the more prominent macro-economic or geopolitical accounts of China’s rise in Asia. The concept of “neighboring” (Saxer and Zhang Citation2016) grasps the complexities of actor interaction in the field of resource extraction highlighted in all contributions well: it puts its focus on the interactions between actors in contact zones of borderlands, which are often ambivalent or fraught with tension. By doing so, “neighboring” refers to the messiness rather than orderliness of the borderland condition, which challenges the outcome of resource sector development policies in the margins of state. Thus, the reality of resource extraction is often much more complex than state policies suggest, with key actors often being side-lined, access to land resources restricted, and (transboundary) resource commodification being hindered by customs regulations. Moreover, the very different dynamics of Chinese investments and their drivers, the diverse perceptions thereof, and the variety of local consequences point to the importance of local agency that is always shaped by a unique local context and history.

Going through the themes assessed by the contributions of this special issue, ranging from mining issues vis-à-vis national development in the Sino-Mongolian borderlands to questions of agricultural transformation in the Golden Triangle, two important analytical directions for future research in this field, bringing together borderlands studies, resource geographies, and BRI research, can be identified. First, the commonalities and differences found in the six case studies call for more comparative research perspectives, which could provide new insights on drivers and consequences by taking into account, for instance, the role of different agro-ecologies or political-institutional path dependencies when tracing the very different dynamics of Chinese agribusiness investments in Southeast vs. Central and South Asia.

Second, the articles have demonstrated how critical it is to take a holistic and multi-scalar perspective to make sense of the complex dynamics shaping transboundary resource use, which should be the main methodological direction for future research on these themes. It makes little sense, for instance, to look at economic and geopolitical drivers of transboundary agricultural investments in isolation from the strategic partnerships with local actors as well as processes of confrontation and cooperation, as the outcomes are ultimately always co-produced by many actors and processes operating at different levels of scale. Therefore, holistic research concepts and analytical lenses such as assemblage or “neighboring” that allow for incorporating the flexibilities of empirical processes rather than trying to isolate them should be the way forward.

While the contributions to this special issue have shed light on some important topics of transboundary development in natural resource use in China’s neighborhood, emerging future research themes will require similar analytical lenses. Growing demand for natural resources in a time of increasing scarcity due to climate change will likely lead to more land use issues and conflict, affecting Asian borderlands considerably. Moreover, new avenues of innovative processes will likely reshape natural resource use in Asian borderlands and beyond, with transboundary flows of technology, knowledge and ideas, especially in the field of agriculture, already playing an increasing role in BRI-related policies and developments. These are important fields of research that require locally grounded, holistic research approaches, not only in the context of China’s neighborhood but also more generally for questions of transboundary resource use involving resource-rich places and more powerful actors from abroad.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahearn, Ariell, and Troy Sternberg. 2023. “Ruins in the Making: Socio-Spatial Struggles Over Extraction and Export in the Sino-Mongolian Borderlands.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 64 (7–8): 919–942. https://doi.org/10.1080/15387216.2022.2132971.

- Alff, Henryk. 2016a. “Getting Stuck within Flows: Limited Interaction and Peripheralization at the Kazakhstan–China Border.” Central Asian Survey 35 (3): 369–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/02634937.2016.1210860.

- Alff, Henryk. 2016b. “Introduction – Special Issue ‘Beyond Silkroadism: Contextualizing Social Interaction Along Xinjiang’s Borders’.” Central Asian Survey 35 (3): 327–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/02634937.2016.1216496.

- Alff, Henryk, Talgarbay Konysbayev, and Ruslan Salmyrzauly. 2023. “Old Stereotypes and New Openness: Discourses and Practices of Trans-Border Re- and Disconnection in South-Eastern Kazakhstan’s Agricultural Sector.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 64 (7–8): 896–918. https://doi.org/10.1080/15387216.2023.2169184.

- Bakker, Karen, and Gavin Bridge. 2006. “Material Worlds? Resource Geographies and the ‘Matter of Nature’.” Progress in Human Geography 30 (1): 5–27. https://doi.org/10.1191/0309132506ph588oa.

- CCICED. 2019. “Green Belt & Road Initiative and 2030 SDGs. Special Policy Study Report.” China Council for International Cooperation on Environment & Development, Accessed July 6, 2020. http://www.cciced.net/cciceden/POLICY/rr/prr/2019/201908/P020190830114510806593.pdf.

- Dong, Min, and He Jun. 2018. “Linking the Past to the Future: A Reality Check on Cross-Border Timber Trade from Myanmar (Burma) to China.” Forest Policy and Economics 87:11–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2017.11.002.

- Dörre, Andrei. 2014. Naturressourcennutzung im Kontext struktureller Unsicherheiten. Eine Politische Ökologie der Weideländer Kirgisistans in Zeiten gesellschaftlicher Umbrüche. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag. https://doi.org/10.25162/9783515107662.

- Garlick, Jeremy. 2018. “Deconstructing the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor: Pipe Dreams versus Geopolitical Realities.” Journal of Contemporary China 27 (112): 519–533. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2018.1433483.

- Grant, Andrew. 2020. “Crossing Khorgos: Soft Power, Security, and Suspect Loyalties at the Sino-Kazakh Boundary.” Political Geography 76:102070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2019.102070.

- Heslop, Luke, and Galen Murton, eds. 2021. Highways and Hierarchies: Ethnographies of Mobility from the Himalaya to the Indian Ocean. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Ho, Peter. 2006. “Trajectories for Greening in China: Theory and Practice.” Development and Change 37 (1): 3–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0012-155X.2006.00467.x.

- Hofman, Irna. 2022. “Tajikistan”. The People’s Map of Global China (Blog), Accessed July 10, 2023. https://thepeoplesmap.net/country/tajikistan/.

- Huber, Matt. 2019. “Resource Geography II: What Makes Resources Political?” Progress in Human Geography 43 (3): 553–564. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132518768604.

- Jackson, Sarah, and Devon Dear. 2016. “Resource Extraction and National Anxieties: China’s Economic Presence in Mongolia.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 57 (3): 343–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/15387216.2016.1243065.

- Joniak-Lüthi, Agnieszka. 2016. “Roads in China’s Borderlands: Interfaces of Spatial Representations, Perceptions, Practices, and Knowledges.” Modern Asian Studies 50 (1): 118–140. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X1500013X.

- Joniak-Lüthi, Agnieszka. 2020. “A Road, a Disappearing River and Fragile Connectivity in Sino-Inner Asian Borderlands.” Political Geography 78:102122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2019.102122.

- Karrar, Hasan. 2021. “Caravan Trade to Neoliberal Spaces: Fifty Years of Pakistan-China Connectivity Across the Karakoram Mountains.” Modern Asian Studies 55 (3): 867–901. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X20000050.

- Karrar, Hasan. 2022. “Just Add Infrastructure? Ambivalence Towards BRI in Unremarkable Places.” Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy, Accessed July 11, 2023. https://munkschool.utoronto.ca/beltandroad/article/just-add-infrastructure-ambivalence-towards-bri-in-unremarkable-places/.

- Liao, Jessica. 2019. “A Good Neighbor of Bad Governance? China’s Energy and Mining Development in Southeast Asia.” Journal of Contemporary China 28 (118): 575–591. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2018.1557947.

- Lin, Shaun, Naoko Shimazu, and James Sidaway. 2021. “Theorising from the Belt and Road Initiative (一带一路).” Pacific Viewpoint 62 (3): 261–269. https://doi.org/10.1111/apv.12322.

- Lu, Juliet. 2017. “Tapping into Rubber: China’s Opium Replacement Program and Rubber Production in Laos.” Journal of Peasant Studies 44 (10): 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2017.1314268.

- Lu, Juliet, and Mike Dwyer. 2023. “Peripheral Centers: Vertical Politics and the Geography of Chinese Cross-Border Opium Replacement in Southeast Asia’s New Golden Triangle.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 64 (7–8): 811–841.

- Murton, Galen, and Austin Lord. 2020. “Trans-Himalayan Power Corridors: Infrastructural Politics and Chi-Na’s Belt and Road Initiative in Nepal.” Political Geography 77:102100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2019.102100.

- Nyíri, Pal, and Joana Breidenbach. 2008. “The Altai Road: Visions of Development Across the Russian–Chinese Border.” Development and Change 39 (1): 123–145. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2008.00471.x.

- Nyíri, Pal, and Danielle Tan. 2016. Chinese Encounters in Southeast Asia: How People, Money, and Ideas from China are Changing a Region. Seattle: Washington University Press.

- Oakes, Timothy. 2012. “Looking Out to Look In: The Use of the Periphery in China’s Geopolitical Narratives.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 53 (3): 315–326. https://doi.org/10.2747/1539-7216.53.3.315.

- Panibratov, Andrei, Alexey Kalinin, Yugui Zhang, Liubov Ermolaeva, Vladimir Korovkin, Konstantin Nefedov, and Louisa Selivanovskikh. 2022. “The Belt and Road Initiative: A Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Agenda.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 63 (1): 82–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/15387216.2020.1857288.

- Parham, Steven. 2017. China’s Borderlands: The Faultline of Central Asia. London: IB Tauris.

- Rippa, Alessandro. 2020a. Borderland Infrastructures: Trade, Development, and Control in Western China. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Rippa, Alessandro. 2020b. “Mapping the Margins of China’s Global Ambitions: Economic Corridors, Silk Roads, and the End of Proximity in the Borderlands.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 61 (1): 55–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/15387216.2020.1717363.

- Rippa, Alessandro, and Yang. Yang. 2017. “The Amber Road: Cross-Border Trade and the Regulation of the Burmite Market in Tengchong, Yunnan.” TRaNs: Trans-Regional and -National Studies of Southeast Asia 5 (2): 243–267. https://doi.org/10.1017/trn.2017.7.

- Ryzhova, Natalia, and Sergei Ivanov. 2023. “Post-Soviet Agrarian Transformations in the Russian Far East. Does China Matter?” Eurasian Geography and Economics 64 (7–8): 943–969. https://doi.org/10.1080/15387216.2022.2064892.

- Sarma, Jasnea, Alessandro Rippa, and Karin Dean. 2023. “‘We Don’t Eat Those Bananas’: Chinese Plantation Expansions and Bordering on Northern Myanmar’s Kachin Borderlands.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 64 (7–8): 842–868. https://doi.org/10.1080/15387216.2023.2215802.

- Saxer, Martin, and Juan Zhang, eds. 2016. The Art of Neighbouring: Mediating Borders Along China’s Frontiers. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Sidaway, James, and Chikh Yuan Woon. 2017. “Chinese Narratives on ‘One Belt, One Road’ (一带一路) in Geopolitical and Imperial Contexts.” The Professional Geographer 69 (4): 591–603. https://doi.org/10.1080/00330124.2017.1288576.

- Spies, Michael. 2018. “Changing Food Systems and Their Resilience in the Karakoram Mountains of Northern Pakistan: A Case Study of Nagar.” Mountain Research and Development 38 (4): 299–310. https://doi.org/10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-18-00013.1.

- Spies, Michael. 2023. “Promises and Perils of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor: Agriculture and Export Prospects in Northern Pakistan.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 64 (7–8): 869–895. https://doi.org/10.1080/15387216.2021.2016456.

- Summers, Tim. 2016. “China’s ‘New Silk Roads’: Sub-National Regions and Networks of Global Political Economy.” Third World Quarterly 37 (9): 1628–1643. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2016.1153415.

- Summers, Tim. 2019. “The Belt and Road Initiative in Southwest China: Responses from Yunnan Province.” The Pacific Review 34 (2): 206–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/09512748.2019.1653956.

- Toktomushev, Kemel. 2021. “A Pesky Story of Chinese Mining in Kyrgyzstan.” In The Impact of Mining Lifecycles in Mongolia and Kyrgyzstan, edited by Troy Sternberg, Kemel Toktomushev, and Byambabaatar Ichinkhorloo, 15–32. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003097341-3.

- Tortajada, Cecilia, and Hongzhou Zhang. 2021. “When Food Meets BRI: China’s Emerging Food Silk Road.” Global Food Security 29:100518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2021.100518.

- Van Schendel, Willem, and Erik de Maaker. 2014. “Asian Borderlands: Introducing Their Permeability, Strategic Uses and Meanings.” Journal of Borderlands Studies 29 (1): 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2014.892689.

- Wesz Junior, Valdemar João, Fabiano Escher, and Tomaz Mefano Fares. 2021. “Why and How is China Reordering the Food Regime? The Brazil-China Soy-Meat Complex and Cofco’s Global Strategy in the Southern Cone.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 50 (4): 1376–1404. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2021.1986012.

- Woodworth, Max D., and Agnieszka Joniak-Lüthi. 2020. “Exploring China’s Borderlands in an Era of BRI-Induced Change.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 61 (1): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/15387216.2020.1727758.

- Yeh, Emily Ting. 2009. “Greening Western China: A Critical View.” Geoforum 40 (5): 884–894. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2009.06.004.

- Yeh, Emily Ting. 2013. Taming Tibet: Landscape Transformation and the Gift of Chinese Development. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.