ABSTRACT

Following the dissolution of the USSR, the restructuring of borders reshaped a space previously characterized by territorial continuity. While many of these borders gained international recognition, others, like those of Abkhazia and Transnistria, remained de facto, lacking acknowledgement from most sovereign states. Despite scholarly recognition that de facto statehood is detrimental to social welfare, the impact of contested borders on welfare provisions remains underexplored. this article analyses how this multiplication of contested (in)tangible borders impacts the activities of Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) as crucial actors in the provision of social services in Transnistria and Abkhazia. The complex geopolitical dynamics of these borderlands necessitate an examination of border-making practices, considering the interplay between Transnistrian and Abkhazian CSOs, Moldovan and Georgian authorities, and Transnistrian and Abkhazian authorities. International organizations, donors, and Russia also play substantial roles. The analysis reveals that each actor controls critical resources such as access, funding, know-how, and symbolic capital. Consequently, CSOs exhibit agency both locally, when interacting with de facto authorities, and at regional and international levels when engaging with external donors and organizations.

Introduction

In 1991, the end of the USSR resulted in the formation of 15 independent countries, leading to substantial changes concerning the presence and location of borders across the region (Anderson Citation2013). Several territorial entities claimed an independent status, yet they were peacefully (e.g. the Republic of Tatarstan) or forcibly (e.g. Chechenia) reintegrated into a fully-fledged state or remained de facto independent, as the conflict in which they were involved froze (De Tinguy Citation2009; Óbeacháin, Comai, and Tsurtsumia-Zurabashvili Citation2016). In this second scenario, these entities became de facto states whose territories are marked by de facto borders – also labeled as “Administrative Boundary Lines” (ABL) by international organizationsFootnote1 (European Union External Action Citation2017; UNICEF Georgia Citation2020). These political and administrative divisions translate into contested territorial boundaries, which create a series of effects on the everyday lives of those living on both sides of these frontiers (Blakkisrud and Kolstø Citation2011; O’Loughlin et al. Citation2011). Despite the knowledge that de facto statehood has a major impact on redistributive policies (Blakkisrud and Kolstø Citation2011), the impact that the establishment and functioning of these contested borders generate on social welfare realities have received only marginal attention (Kolossov and O’Loughlin Citation2011). Importantly, Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) play a significant role as providers and/or mediators of social welfare in the post-Soviet spatial area, including in its de facto state entities. Yet, the impact produced by de facto borders, and the many bordering practices related to the functioning of CSOs, and how these organizations navigate the complex geopolitical landscape, has never been addressed in the academic literature.

For these reasons, this article presents an exploratory study (Elman, Gerring, and Mahoney Citation2020) of how de facto borders can serve to (re)produce other borders and, with them, a series of related bordering practices at different scales, namely local, regional and international. The article analyses how such proliferation of borders impacts the activities of CSOs as crucial actors providing social services in Transnistria and Abkhazia. With social welfare provision, we refer to efforts made to meet societal needs through the provision of, or the mediation of access to, concrete resources and services (Cammett and MacLean Citation2011). Although several de facto states are located across former Soviet countries, Abkhazia and Transnistria were selected because of their relative accessibility – e.g. in terms of them being not militarizedFootnote2 – and because their partition through the establishment of de facto borders happened more than 30 years ago. This period did not only allow CSOs to develop activities within this context, but it also meant that de facto border-making and the resulting bordering practices emerged strongly to impact locals’ daily lives – being thus more visible to the researcher’s eyes. Moreover, Abkhazia and Transnistria feature interesting variations in terms of citizenship policies, (geo)political dynamics, and geographical positioning (Eastern Europe and the Caucasus region), making them particularly suitable to study how border-making and the connected bordering practices function and how they are generated from the establishment and management of de facto borders.

In what follows, we start with an outline of the complex geopolitical environment in which de facto states evolve and explain why we consider the concepts of border-making and bordering practices as valid analytical frameworks between the many available within the broad field of border studies, to analyze the interactions between geopolitics and social welfare provision at different scales. Next, we explore how such bordering practices can be investigated within a triangular relation of relevant actors.

De facto states from a border lens: border making and everyday bordering

De facto states are characterized as entities having a permanent population, a defined territory and a government (Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States Citation1933). Importantly, however, a de facto state is not in a (full) capacity to enter into relations with other states because it lacks (full) international recognition of its territorial borders and, thus, of its sovereign status (Pegg Citation1998). Seen from such perspective, a de facto state remains an emanation of the state from which it parted and claims its reintegration. De facto states’ disputed borders reflect this complex geopolitical macro-landscape, turning these contested territories into quintessential borderlands where every day social life is strongly impacted by the regional and international power struggles.

Both for Transnistria and Abkhazia, the strained geopolitical relations between the European Union (EU) and Russia have a clear local impact (Kolossov Citation2005). The EU follows a strict nonrecognition policy, yet it still engages with de facto states’ authorities in stabilization processes to avoid flare-ups of conflicts and to balance Russia’s involvement in the region (Harzl Citation2018). Since 2009, this interaction is framed by the Non-Recognition and Engagement Policy in the case of Abkhazia and the Confidence Building Measures (CBM) in the case of Transnistria. These two frameworks include support to CSOs providing social welfare services, which indicates the geopolitical salience for the EU in this area. In the case of Abkhazia, the EU is also closely present through the EU monitoring mission (EUMM) set up in September 2008 in the aftermath of the conflict over South Ossetia also spanning in Georgia and Abkhazia. However, EUMM’s mandate is limited to observations on the Georgian-controlled side. In contrast, Russia’s recognition of Abkhazia as a state facilitates Russia’s engagement not only in political and strategic areas but also in economic and social aspects. Russia also engages with Transnistria although it does not recognize it as a state. One influential tactic is “passportization”, which entails the distribution of Russian passports to Abkhazia and Transnistria’s inhabitants, yet these passports are not accepted by many countries including the EU and Schengen countries which deny visas to their holders. Russia also provides direct budgetary support and financial benefits, which significantly affect social welfare provision in both Abkhazia and Transnistria.

As their de facto borders were established and their functioning institutionalized, both Transnistria and Abkhazia came to have features of a state, with a president acting as head of the state, a government, and a parliament. Over their 30 years of existence, the physical de facto border translated into full-fledged state-like system with less tangible boundaries (re)produced in increasingly diverse legislative corpus, including a constitution and laws, and modes of administrations operating on the two sides of the frontier, telecommunication systems, banking systems and currencies. In a mutual and multidirectional relation, de facto states thus (re)produce a variety of tangible and less tangible de facto borders (Blakkisrud and Kolstø Citation2011).

However, due to the international pressures shaping local socio-economic, political and cultural life as well as everyday exchanges across the de facto border, we expect also bordering practices to be highly visible and impactful in these geopolitically loaded borderlands. As we understand de facto borders as social, political and discursive constructs (Newman and Paasi Citation1998), they are also reproduced in everyday encounters through “discourses, political institutions, attitudes and everyday forms of transnationalism” (Yuval-Davis Citation2013a, 10). Everyday practices of inclusions and exclusions experienced by local CSOs (i.e. everyday bordering) trying to navigate this borderland, are understood here as both reproducing the and reproduced by de facto borders in a circular/recursive relation (e.g. where the de facto border and everyday bordering practices feed on each other).

Bordering practices operate both within and outside the territorial boundaries of (de facto) states, and therefore have profound social implications for those crossing them and those living away from the frontier (Yuval-Davis, Wemyss, and Cassidy Citation2017, 2). This brings in the concept of borderland, by which we mean two (or more) spaces socio-economically interconnected but separated by a border, here a de facto one, where everyday life is strongly impacted by the border and its interconnected bordering practices, both symbolically and in very real experienced terms (Orsini et al. Citation2019). Like most borderlands, due to the geopolitical centrality of these marginal(ized) territories (Orsini, Canessa, and Martínez Citation2018) at the local level, the establishment of de facto borders and the interconnected bordering practices (Blakkisrud et al. Citation2021) – both as a precondition for, and consequent to, the establishment of the de facto statehood – strongly impact the everyday lives of inhabitants and the (cross-border) provision of social services by CSOs. CSOs in Transnistria and Abkhazia, as in different former Soviet countries (Babajanian, Freizer, and Stevens Citation2005) or less wealthy or weaker states (Batley and Rose Citation2011; Cammett and MacLean Citation2011), are crucial actors interacting with the (de facto) state in social welfare provision. In this research, the term CSO designates all forms of civil self-organization focusing on social services, comprising both formalized structures, non-governmental organizations (NGO) or as part of a larger regional or international organization (international NGO) and more informal associations (Bürkner and Scott Citation2019). By local CSO, we mean a CSO, which is founded and operates in Transnistria or Abkhazia, which is registered according to the local regulation and that is mostly operated by local staff – i.e. people from Transnistria or Abkhazia.

In sum, this research applies the analytical tool of “everyday bordering” developed by (Yuval-Davis Citation2013b) to reveal the impact of legal and political dynamics on shaping the availability and accessibility of social welfare provisions, which, in the selected borderlands, are mediated by CSOs at both the local and regional scales. As such, this study aligns with (Mezzadra and Neilson Citation2013) recommendations to give centrality to the (re)production and operation of tangible and intangible borders to (de)construct the contemporary socio-political and economic world.

Interaction and bordered mediation at different scales in a triangular relationship

(Geo)political relations and the bordering practices that they generate are thus essential in shaping social welfare provision by local CSOs in Abkhazia and Transnistria. Research by Batley and Rose (Citation2011) that investigated the interactions between states and CSOs in social welfare provision argued that this relation is essentially shaped by what they categorized as (1) macro-institutional factors, such as state regime type, authority structure, law constitution and history of state/NGO relations; and (2) meso-institutional factors, such as technical and economic features, power of principals and agents, ideologies or values and political salience, resource dependency, lines of accountability, affiliations and networks, regulations and policies (Batley and Rose Citation2011). More so, it is argued that such interactions are constantly evolving in a loop of engagement, feedback and reengagement. By concentrating on this loop, it becomes possible to show how border making and bordering practices are negotiated in interaction between the above-mentioned actors engaging at different scales, which in fine shape the provision of and access to social services in Abkhazia and Transnistria. From this perspective, de facto state regime with its geopolitically loaded border making and interconnected bordering practices constitute favorite fields to make visible how exclusion/inclusion is (re)produced through de facto borders, and how the actors involved develop strategies to navigate these constellations of (in)tangible boundaries.

Batley and Rose (Citation2011) also point to the importance of CSO/state history of relations and existing resource dependences. In the geopolitical context of de facto states, however, CSOs in Transnistria and Abkhazia are also strongly dependent on resources of international organizations (e.g. UN agencies and offices such as UNDP, UNHCR, UN Women) and donors (EU, Russia, USAID). Our data show that the EU and the UN are perceived in both Transnistria and Abkhazia as “Western”, although both encompass member states not positioned as part of “the West”. INGOs are non-governmental and nonprofit organizations, situated outside the de facto state jurisdiction and employ international and local staff. Donors are (financial) resource providers, who can be institutional, such as the EU and its member states, the US – operating via their embassy or cooperation agency (e.g. USAID, SIDA) – or non-institutional, such as businesses or individuals. In the context of Abkhazia and Transnistria, donors are primarily institutional ones. As international organizations are made of sovereign states, de facto states have no membership and are not part of their collective decision-making process (Caspersen Citation2009). Importantly, international organizations and donors operating in Abkhazia and Transnistria work most of the time from Georgia and Moldova respectively, thus across the de facto border, which has a major impact on their perceptions and actions, in particular in Abkhazia. Hence, the relation between on the one hand, Abkhazia/Georgia and on the other hand, Transnistria/Moldova makes it crucial to investigate borderlands dynamics. Thus, the de facto border divides two interconnected spaces and results in and is the result of a series of local and regional everyday (in)formal strategies of adaptation and resistance to international (geo)political transformations. Moreover, in the context of Transnistria and Abkhazia, the connection between CSOs and Western-(perceived) donors and international organizations triggers in some cases negative public perceptions toward CSOs as donors and international organizations are perceived to diffuse and even impose Western-(perceived) norms and standards (Babajanian, Freizer, and Stevens Citation2005).

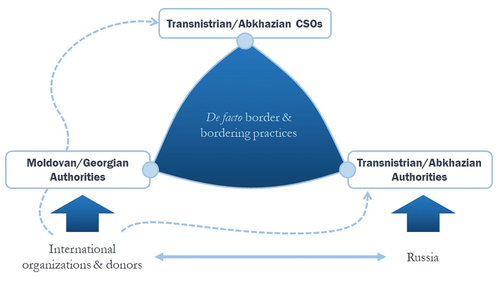

Thus, this complex environment requires a multi-scalar approach where we consider the local scale with Transnistrian and Abkhazian authorities and, across the de facto border, the Moldovan and Georgian authorities. We then transcend the de facto border and move the focus to the regional and international scales, to assess the role of international organizations and donors. Hence, we look at bordering practices arising and negotiated in the provision of social welfare services in the triangular relations between 1) Transnistrian and Abkhazian CSOs, 2) Transnistrian and Abkhazian authorities and 3) Moldovan and Georgian authorities, with a major role played by international organizations and donors on one side and Russia on the other side.

Methodology

The primary data discussed in this article consist of 23 semi-structured online interviews conducted by the first author and a research assistant between March and June 2021, and 12 in-person interviews conducted by the first author in October 2021 with Abkhazian and Transnistrian CSOs leaders and staff, (former) international organization and donor representatives operating in Transnistria, and Abkhazian and Transnistrian authorities’ representatives. All the interviews are indicated in .

Table 1. Interviews.

Sixteen interviews were conducted in English and thirteen in Russian, the main communication language in Transnistria and Abkhazia. Besides interviews, the first author also conducted observations between October 2021 and November 2022 in the cities of Bender, Tiraspol and Ribnitsa for Transnistria, and in Zugdidi, villages such as Rukhi and at the Ingur/Enguri bridge linking the Georgian-controlled territory to Abkhazia. The in-person interviews took place in those places and additionally in Chisinau and Tbilisi. The researchers’ physical access to Abkhazia was denied by the Abkhazian authorities, officially due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

For CSOs leaders and staff members, the questions focused on the interactions that they usually had with donors and international organizations, with an emphasis on the conditionality and constraints they experience. For representatives of donors and international organizations, questions focused on their relations with local CSOs, de facto authorities, Georgia or Moldova’s authorities and the role of Russia. Questions also tackled how the programs and projects were shaped and financed and the main hindrances to their implementation with a focus on border making and bordering practices impacting access to social services in both settings. All the interviews in Russian were translated into English by the first author and the research assistant, and subsequently all the material was coded with the software NVivo. Secondary data such as laws, policies, and practices regarding CSOs in each de facto state were also analyzed, paying particular attention to the relationship between Abkhazian and Transnistrian authorities and local CSOs, in particular those providing social services.

We acknowledge that the authors’ Western positioning. Being affiliated with a university from the Global North might have aroused some suspicion, in particular among the CSOs, as the main researcher could be perceived as an emanation of the Western-(perceived) donors. Yet, not being from any of the parties involved in the geopolitical struggle(s), and knowing Russian, also facilitated access to local CSOs leaders and representatives. The former became evident as the Georgian research assistant – unlike the main researcher – was not granted access to interviews with Abkhazian CSO representatives. Acknowledging our age, gender, and experiences of access to social welfare, we paid a lot of attention to our use of terminology (e.g. “de facto”, “occupied”) and refrained from taking any side. The terms used to name Abkhazia and Transnistria are debated and vary significantly depending on the actors’ positionality to the geopolitical and local conflicts and tensions. Thus, we chose inclusive denominations, being aware of the limitations that this entails.

In the following section, we present the exploration of de facto border making and the resulting bordering practices, as they develop and operate, and impact the social services provision by local CSOs along the triangulated relationship connecting the different local, regional and international actors advancing their agendas in these borderlands as exemplified in the scheme below (see ). The chart illustrates the triangulated connections between the main actors involved in social welfare provision and how their relationship is shaped and contribute to shaping border making and bordering practices in a recursive dynamic.

Local CSOs and de facto authorities: oscillating between defiance and cooperation

In both de facto states, civil society initiatives began mainly after the end of the USSR. While there are differences between the two de facto state entities, in more recent times CSOs providing social services have experienced increasing tensions and limitations in their ability to operate. The analyses revealed that such limitations are enforced within the CSO – de facto state relation through the deployment of legal boundaries and a series of practices of surveillance by the de facto authorities, accompanied by a range of bordering practices constraining CSOs’ activities and their access to (financial) resources. Yet, CSOs engage with the de facto authorities from one side and with representatives of donors and international organizations from the other side, provide feedback on their engagement mainly to mitigate bordering practices and reengage on different terms.

Transnistrian CSOs – Transnistrian authorities

In Transnistria, most CSOs were created after the USSR ended, with local willingness and external (i.e. Western) incentives that entered. De facto authorities’ control over CSOs was extremely tight in the beginning. Yet, this evolved, enabling limited cooperation between the Transnistrian authorities and CSOs providing services in areas such as HIV prevention, tuberculosis treatment, support for survivors of domestic violence and human trafficking, or in advocating for accessibility for persons with disabilities as well as children in foster care (interviews 1 and 2). However, local CSOs’ representatives emphasized that, in recent times, they have experienced again some tightening in the de facto authorities’ control over their activities. This is especially the outcome of the introduction of new laws and practices of surveillance aiming at reducing CSOs’ reach of action and their capacity to operate.

Two laws are crucial institutional factors shaping the relationship between CSOs and Transnistrian authorities, in particular as they set up major limitations for Transnistrian CSOs. The first one is the NGO law, introduced in February 2018. This law strengthens the de facto borders and at the same time is an emanation of this de facto border, as it prohibits CSOs from receiving foreign funding to engage in any kind of ill-defined political activities.Footnote3 The second one, the law on extremist activities which was introduced in August 2020, enables the Transnistrian authorities to qualify CSOs’ activities as “extremist”, leading to potentially severe court decisions.Footnote4 Many respondents highlighted that these two laws copied to a great extent the Russian legislation on similar subjects. While this points to the influence of legal developments in Russia, the Transnistrian NGO law is not as restrictive as the Russian one since Transnistrian authorities cannot significantly curtail foreign funding to CSOs providing essential social services (interviews 1 and 18). Hence, the de facto border nevertheless remains permeable for international locally western-(perceived) support to local CSOs as Transnistrian authorities rely on such external funding and, in some cases, approach CSOs for partnerships (interviews 4 and 5).

However, the real impact of these laws on CSOs stems from their implementation, as the laws give a larger leeway to Transnistrian authorities to monitor CSOs’ activities through increased surveillance. Such control results in a range of bordering practices that tighten further CSOs activities and their ability to access external (financial) resources. CSOs’ representatives interviewed described an “illusion of choice” and an “imitation of dialogue” in their interactions with the Transnistrian authorities, as not responding to “an invitation” for meeting with authorities would have heavy consequences. What is more, Transnistrian authorities monitor the activities of CSOs and their staff by attending their events and scrutinizing the contacts of CSOs representatives especially when these contacts develop across the de facto border (e.g. attending a donors’ forum in Chisinau). All these practices make the de facto border more tangible for Transnistrian CSOs which will choose carefully their partnerships and activities, especially the ones they publicize.

When engaging across the de facto border with international donors and organizations, Transnistrian CSOs have to negotiate the choice of terminology, also because of their tense relationship with the authorities. For instance, donors favor the use of “left and right banks of the Dniester”, or speak of the “Transnistrian region” when they refer to Transnistria. This terminology erases the de facto border between Moldova (right bank) and Transnistria (left bank), being thus problematic for some Transnistrian CSOs whose leaders have to answer to the Transnistrian security services (interview 4). Examples were also mentioned about family members of CSOs representatives who were under pressure. This shows the de facto border as a tangible and challenging reality for the CSOs representatives, which drives them to (re)negotiate interactions with international donors and organizations to meet their terms of engagement.

To discourage CSOs to engage across the de facto border with international donors and organizations to seek external funding, Transnistrian authorities have also set up a presidential grant. Such a grant is modeled on a very similar dispositive available in Russia, where CSOs receiving foreign donations cannot apply for the presidential grant.Footnote5 However, paradoxically, at the same time, the de facto authorities encourage CSOs to apply for international funding to upgrade social services, as their de facto statehood excludes them from receiving external (financial) support. Nevertheless, Transnistrian authorities still actively prevent CSOs from seeking external resources including when they intend to use them in social fields, which according to Transnistrian authorities, could undermine de facto states’ political legitimacy. Transnistrian authorities have issued a list of foreign bodies with whom CSOs are advised not to collaborate under the threat of liquidation, installing a contradictory policy environment when it comes to CSOs’ cross-de facto borders interactions (interviews 6, 14 and 16).

Hence, legal boundaries, restrictive practices and opaque policies result in a hostile environment for CSOs to develop (Cole Citation2020), implement and report on their activities, especially those involving international donors and organizations. Different bordering practices make the de facto border a tangible reality in the everyday functioning of CSOs. As prosecutions occurred in the past, CSOs are careful in choosing their partnerships across the de facto border, or in framing their activities. They will only openly implement those activities, which will be tolerated or even encouraged by the Transnistrian authorities, while they will keep a low profile or even refuse to engage with activities and partnerships, which may trigger suspicion and lead to further surveillance, interrogation and even liquidation. However, despite the constrains, there remains room for Transnistrian CSOs to negotiate firstly at the local level with Transnistrian authorities and, secondly, across the de facto border with donors and international organizations. They thus challenge, resist and, to some extent, shape those very bordering practices, which impact their everyday activities.

Abkhazian CSOs – Abkhazian authorities

In Abkhazia, CSOs started emerging during the Perestroika era in the mid-1980s. Their activities have evolved from the humanitarian assistance that they delivered in the 1990s to foster political dialogue within Abkhazia and with Georgia, as well as by offering education and social services (Popescu Citation2010; Le Pavic et al. Citation2022).

Contrary to Transnistria, CSOs’ activities are not constrained by any legal boundary. However, interviewees from local CSOs and international organizations emphasized ongoing discussions pushed by Russia to pass a law that will approximate the restrictive Russian law on foreign agents, reshaped in 2022 as the law on the control of activities of persons under foreign influence.Footnote6 The law would give increased leeway to the Abkhazian authorities to constrain Abkhazian CSOs’ access to (financial) resources across the de facto border and restrict their activities.Footnote7 Although this law has not been passed yet, many interviewees from international organizations, donors and local CSOs alike, expressed their concerns and hope that Abkhazian authorities will not be in a position to set this legal boundary, due to their lack of (financial) resources and strong resistance from well-respected Abkhazian civil society actors (interviews 7, 8 and 9). However, as Transnistrian authorities, the Abkhazian ones are well aware that CSOs provide essential social services and thus engage with local CSOs to create loopholes for CSOs to still receive external funding (interview 21), hence keeping the de facto border porous. The interactions in this multi-layered borderland are shaped by financial and (geo)political realities as Russia supports 50% of the Abkhazian’s budget and even 80% of regalian functions performed by the de facto Abkhazian ministries of defense and internal affairs (Esiava Citation2019). This cross-de facto border influence is negotiated within Abkhazia, at the local scale, by the tight kin-linkage resulting from the small size of Abkhazia and even more of the Abkhaz ethnic group. These links shape the connection between Abkhazian authorities and Abkhazian CSOs giving the latter a leeway in the negotiation loop, including to keep engaging across the de facto border with Georgia.

However, even without this new law, legal boundaries in Abkhazia are already impacting CSOs’ activities in particular those providing support to survivors of domestic and gender-based violence. The issue of gender-based violence must be seen as framed within a geopolitical struggle between the facially western-oriented Georgia – where a law on domestic violence was passed despite strong internal opposition as part of the EU approximation conditionalityFootnote8 (Shevtsova Citation2022) – and a Russia-oriented Abkhazia – where gender-based and domestic violence are denied or seen as a private matter (interview 8). The Abkhazian legal environment restricts CSOs from providing services to survivors of gender-based and domestic violence, for example by limiting services to working hours, preventing a hotline from operating 24/7, or a shelter from being opened. This distinct Abkhazian legal environment makes the de facto border tangible in the provision of a specific service which is challenged via informal practices of CSOs staff (e.g. using their private mobile phone and hosting survivors in their private places) (interview 21).

However, as in the case of Transnistria, the consequences of (pending) legal boundaries are fluctuating, depending on the de facto authorities’ tolerance or level of enforced surveillance. Personal preferences of the person in charge are often key as indicated by several respondents in the case of a former head of administration in Gal(i) – the district where most of the Georgian population in Abkhazia reside – who was hostile toward CSOs’ presence to one supporting them. This change enabled CSOs to expand their activities, including those carried out across the de facto border for which CSOs rely on the support of international organizations and donors, as well as INGOs. In opposite direction, respondents indicated that the current Abkhazian de facto Minister of foreign affairs is using his leverage to prevent CSOs from engaging across the de facto border, in particular with Georgian counterparts, and he acts to seal off Abkhazia from the international western-(perceived) presence, restricting access across the Georgian-Abkhazian de facto border and declaring a UN official persona non grata.Footnote9 This shows the high politicization of access to Abkhazia in a regional context that became even more volatile as Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine results in an indirect confrontation with the EU and the US at a more international scale. Such a tense climate impacts international access to Abkhazia where de facto authorities scrutinize even closer CSOs activities. Surveillance is implemented through regular interviews of CSOs representatives and Abkhazian staff working for international organizations, by the Abkhazian State Security Service (the so-called “triple S”). However, Abkhazian CSOs keep engaging with de facto authorities, using their interpersonal linkage to negotiate legal boundaries and practices of surveillance, to mitigate the impediments to CSOs’ activities in an increasingly constrained environment at the regional and more international scale. In the Abkhazian context, interpersonal ties seem to be more prevalent in the engagement than in the Transnistrian one, as Abkhazia is a smaller de facto state where ethnic and kin ties remain prevalent through affiliations and networks. This informs the loop of engagement, feedback and reengagement allowing to some extent Abkhazian CSOs to influence through feedback, the Abkhazian political agenda, including to amend the making of legal boundaries and bordering practices shaping their activities and their access to international (financial) resources.

De facto authorities and the state they parted from: a limited engagement guided by a nonrecognition policy

Moldovan and Transnistrian authorities on the one side, and Georgian and Abkhazian authorities on the other, have no official relations. This is because Moldovan and Georgian authorities consider Transnistria and Abkhazia respectively as part of their territories, thus granting no legitimacy to the Transnistrian and Abkhazian authorities as part of a nonrecognition policy. In the case of Moldova and Transnistria, the Confidence Building Measures framework (CBM) regulates the cooperation “between both banks of the Diester River”. The Georgian-Abkhazian relationship is tenser and, apart from the Geneva negotiations process on conflict settlement, both authorities have little contact in the framework of the engagement without a recognition strategy. This section analyses how these frameworks of cooperation are used to negotiate legal boundaries and bordering practices making the de facto border tangible and impacting CSOs providing social services.

Transnistrian – Moldovan authorities

The Confidence Building Measures (CBM), enforced since 2009 and currently in its fifth phase, is a holistic framework for the Moldovan-Transnistrian cross-de facto border cooperation. This program, funded by the EU, is implemented by UNDP. According to one interviewee, UNDP has “the knowledge, the capacity to implement projects in Transnistria and on the right bank and the necessary impartiality” (interview 11). The CBM is conceived as a multi-dimensional approach, aiming at supporting “business links and entrepreneurship, social infrastructures, civil society development, healthcare and environmental protection” (UNDP Citation2018). In other words, with the consent of the Moldovan authorities, international donors and organizations are allowed to navigate the de facto border and cooperate with Transnistria on social services provision, yet operating from the Moldovan-controlled territory. To some extent, this gives the Moldovan authorities leverage to influence the development of social services in Transnistria through activities such as training and best practices sharing with practitioners “from the right bank” (UNDP Citation2016). This although some in Moldova think that social services in Transnistria should remain underdeveloped so that the Transnistrian population would have to go further to Moldova (e.g. to Chisinau) to access social services and ultimately aspire to be united with Moldova (interview 1).

Yet, also the Transnistrian authorities aim to keep control over external funding and interventions. Donors and international organizations operating from Moldova and willing to work in Transnistria, have first to register at the “Transnistrian Ministry of Foreign Affairs”. Donors are aware that this process gives the Transnistrian authorities a leeway to control their action but accept it, emphasizing their “transparency” vis-à-vis the Transnistrian authorities, and keeping in mind the interest of the local CSOs they collaborate with (interview 11). Second, donors and international organizations have to get the approval of the Transnistrian Coordination Council for Technical Cooperation. The agency’s contact person first needs to be notified of the project (e.g. the budget, timeframe, and benefits for Transnistria), of which (s)he “makes sure there are no political activities intended to be conducted by the donor” (interview 11). The project is then presented to the council members and, if approved, can be implemented in Transnistria. This again shows how interpersonal relations are crucial, “with a major role played by the contact person of the coordination council” (interviews 11 and 18).

International organizations and donors’ representatives, all operating in Transnistria from the Moldovan-controlled territory, described an evolution in their relationship with the Transnistrian authorities toward more openness and trust. The Coordination Council for Technical Cooperation which used to be “a filter, rejecting about 80% of projects except for infrastructural ones, is now more conducive” (interview 11). This is probably the case since the Transnistrian authorities and international donors and organizations have engaged multiple times over 30 years. Donors know the conditions, which enable cooperation and the activities that will be vetoed by the Transnistrian authorities.

The personal preferences of the person in charge on the Transnistrian side can vary from complete refusal to openness for collaboration, which translates into bringing in international expertise and applying their recommendations (e.g. UNICEF being involved in the activities of a school for children with special needs managed by the de facto Ministry of Interior in Transnistria). In some cases, Transnistrian representatives take part in activities organized by international donors and organizations such as round tables and study visits to EU countries (e.g. to Sweden to see how the services provided by CSOs are contracted by local authorities). To avoid fluctuations based on personal preferences, international donors and organizations are advocating signing a Memorandum of Understanding with the de facto authorities (interview 17). This would institutionalize further their relations across the de facto border.

To some extent, the protracted conflict between Moldova and Transnistria is also attracting more resources from donors and international organizations, as highlighted by a representative of the Transnistrian authorities (interview 3):

The conflict we are having with Moldova is nothing more than an administrative conflict, we argue over the language, we don’t want to speak Romanian (…) apart from that nothing is opposing us. However, Moldova is taking advantage of it to attract international attention (…) as a result Moldova receives more funds from the EU, from the US so it’s advantageous.

This may result in more (financial) resources being made available for CSOs’ activities, yet access to these resources remains constrained by differences in languages, phone dials, banking systems and currencies; a series of gaps, all consequent to the de facto nation-state building and the operation of the de facto border between Moldova and Transnistria.

The difference in languages is one of the most prominent, as Romanian is the only official language in Moldova since 2010, although Russian remains largely spoken, all the administrative documents are now issued in Romanian only and Russian is “a dying skill in Moldova” (interview 17). Whereas in Transnistria, Russian remains the main spoken language and is an official language alongside Ukrainian and Moldovan. As Russian knowledge is decreasing in Moldova and Romanian was never a prominent language in Transnistria, communication is likely to be further hampered in the near future, not only for authorities but also in people-to-people contacts, thus making the de facto border an even more tangible reality.

Last but not least, the passportization policy fostered by the de facto statehood has a strong impact on the possibility to navigate (de facto) borders not only at the local level (e.g. de facto border of Transnistria with Moldova and Ukraine) but also at the regional level, to enter Russia and the Schengen space. Many Transnistrian inhabitants hold several passports, as the Transnistrian authorities allow multiple citizenships on top of the Transnistrian one and the Transnistrian passport is not recognized anywhere. Transnistria never gained any international recognition nor did it unite with the Russian Federation, despite a referendum, which was held in 2006 where 97.2% of the voters supported joining Russia.Footnote10 However, many Transnistrian inhabitants hold a Russian passport enabling them to travel to Russia including to access healthcare, although not always free of charge, and to receive pension supplements (interviews 7 and 9, see also Ganohariti Citation2020).

Although, there is no official relation between Moldovan and Transnistrian authorities, both engage informally, impacting access for international donors and organizations to Transnistria. Over the years, the interactions between Transnistrian authorities and international organizations and donors have made the de facto border more porous, resulting in an increase international support for social services provision by local CSOs.

Abkhazian – Georgian authorities

The UN-led Confidence Building Programme (COBERM) and the “engagement without recognition strategy” framed the cooperation between Abkhazian and Georgian authorities. Our data show that COBERM is mostly rejected by Abkhaz actors aiming at an independent development from Georgia and was initially thought to be the vehicle for the distribution of the so-called neutral passport largely rejected by Abkhaz as it was issued in and by Georgia. Both Abkhazian authorities and CSOs tend to relinquish (financial) support coming from Georgia and favor a direct relationship with international donors and organizations, which is further complicated by the de facto statehood. Since the end of the UN mission in 2008, no mandate is in place for the UN and its agencies to operate in Abkhazia and all the cooperation relies on a “Gentleman’s agreement”. This results in strong variations according to the person in charge, as exemplified by the change in the de facto Abkhazian Minister of foreign affairs from Daur Kove to Inal Ardzinba in November 2021.

Yet, still, together with some INGOs and a few EU representatives, the UN is one of the only international actors entering Abkhazia and having offices in Sukhum(i) for 7 out of 18 of its agencies. The EU monitoring mission (EUMM) can only operate on Georgian-controlled territory. Yet, contrary to Transnistria, the relations between international donors and organizations and Abkhazian authorities remain informal, with no institutionalization, thus giving a large room for maneuver to the Abkhazian authorities, which can restrict access to international donors and organizations instrumentalizing their partial control of the de facto border.

The relationship between both Abkhazian and Georgian authorities remains tense as the Georgian authorities consider Abkhazia “a part of Georgia occupied by Russia” (Bakradze Citation2018) and have set a Government of the Autonomous Republic of Abkhazia based in Tbilisi and which is the official interlocutor of the Georgian authorities on Abkhazian matters. Since 2008, the Georgian Law on Occupied Territories imposes that all activities of international donors and organizations in Abkhazia should be humanitarian only, prohibiting any economic and financial interventions.Footnote11 What is at stake is avoiding the consolidation of the de facto statehood (e.g. payment of taxes by businesses started by grants aiming at supporting social and economic entrepreneurship). Thus, before crossing the de facto borders, international donors and organizations have to negotiate not only with the Abkhazian authorities but also with the Georgian ones. The Georgian law on Occupied Territories acts as a legal boundary to their activities in Abkhazia and gives the Georgian authorities the power to control their activities across the de facto border as all projects implemented in Abkhazia must receive “a non-objection order” from the Georgian State Ministry for Reconciliation and Civic Equity (SMRCE). Donors interviewed describe that they provide a broad description of the project and are sometimes called “for talks”, also with the Georgian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (interview 7). Interviewees mentioned that it is important to frame their activities as “humanitarian” even 30 years after the end of the Georgian-Abkhazian war and although they are expanding further than humanitarian relief.

The de facto border existence and selective closure steer the type of interventions CSOs are doing, it shapes access to services and social issues and hence interventions to address social needs. Family separation is one of the main consequences of these closures, leading to frequent elderly isolation (an issue occurring also across Abkhazia) since families remain the first care providers in the area. To tackle this issue, a retirement home was built with the support of international donors and organizations and is operated by a local CSO in Rukhi, the last village on the Georgian-controlled side of the de facto border. In 2011, a hospital was built and is today providing methadone to drug users. As methadone is forbidden in Abkhazia, dozens of beneficiaries are crossing the de facto border daily, resulting in a very high transportation cost, time spent and increased social stigma among their communities. Thus, Georgian authorities have set up medico-social facilities with the support of international donors and organizations in the borderland of the Zugdidi (on the Georgian-controlled side) – Gal(i) districts. The two cities separated by the de facto border, are 20 km away from each other and they are strongly interconnected when it comes to economic and social ties. These ties are severely disrupted when selective closures of the de facto border occur at the main controlled crossing point located at Ingur/Enguri. It is there where the Georgian police operate by checking and registering anyone crossing into Abkhazia, giving thus more saliency to the de facto border which became more difficult to navigate as the number of controlled-crossing points decreased since 2016–2017. Nowadays, Phakhulani/Saberio remains the only other controlled crossing point between the Georgian-controlled territory and Abkhazia where no controls are implemented by the Georgian authorities. Three other crossing points (Khurcha/Nabakevi, Shamgona/Tagiloni and Orsantia/Otobaia) have been closed from Abkhazia to redirect the crossing to Ingur/Enguri where the Russian FSB operates. As the Georgian-Abkhazian de facto border is becoming less porous, illegalized crossings increased, including to access social services on the Georgian-controlled side, in some cases with tragic consequences (State Security Service of Georgia Citation2021).

Lastly and as is the case of Transnistria/Moldova, differences in languages, banking systems and currencies resulting from the Abkhazian de facto state building over 30 years are making the de facto border tangible in everyday life. The language gap is widening as Russian remains the main language spoken in Abkhazia but since 2008, Russian is less taught in Georgia and Georgian is almost not taught anymore in Abkhazia, including in the Gal(i) district where the majority of the Georgian and Megrelian (a sub-ethnic group of Georgians) population is living (Kotova and Partzvania Citation2021). Megrelian language tends to be the main communication language in the Gal(i)-Zugdidi borderland but is not spoken across Abkhazia and Georgia.

Hence, the tense Abkhazian – Georgian authorities relation results in a reduced margin of actions for Abkhazian CSOs and challenges their access to (financial) resources from Western-(perceived) donors and organizations. Yet, in some cases, the position of Abkhazian authorities and CSOs aligned, in particular in stressing their distinctiveness from Georgia and their willingness to make Abkhazia at least facially recognized as a fully-fledge state.

Local CSOs and Moldovan/Georgian authorities: negotiating border making and bordering practices

There is no cooperation between Moldovan authorities and Transnistrian CSOs, or Georgian authorities and Abkhazian CSOs. Instead, cooperation happens at the CSO level, with Moldovan and Georgian CSOs engaging with Transnistrian and Abkhazian CSOs, respectively. This cooperation at the CSO level is instrumental for the donors’ confidence-building strategy to ease the prevalence of the de facto borders through people-to-people contacts, social support and technical cooperation. Despite this, Transnistrian and Abkhazian CSOs tend to prefer direct relationships with international organizations and donors. However, international donors and organizations remain tied to the nonrecognition policy aligning with the Moldovan and Georgian authorities. As a result of the nonrecognition policy of Georgia and Moldova toward Abkhazia and Transnistria, Abkhazian and Transnistrian CSOs are one of the main vehicles of engagement across the de facto border. Border-making results in bordering practices that significantly impact CSOs’ activities, including those aiming at providing social services, yet Transnistrian and Abkhazian CSOs retain agency to overcome these bordering practices in their feedback and reengagement with international donors and organizations. These negotiations happen mostly at the international scale, directly with representatives of international donors and organizations, which remain the main (financial) resources provider to Transnistrian and Abkhazian CSOs across the de facto borderlines.

Transnistrian CSOs – Moldovan authorities

Our data show no direct relations between Transnistrian CSOs and Moldova authorities, yet as all international donors and organizations operate from the Moldovan-controlled territory, all their international and local staff are based there. The cooperation with Transnistrian CSOs providing social services is negotiated via Moldovan (non)governmental entities as part of the CBM process to mitigate the effects of the different political, administrative and monetary systems.

International donors and organizations are in the position to set the conditionality of (financial) support to Transnistrian CSOs. In some cases, cross- de facto border cooperation through a partnership between a Transnistrian and a Moldovan CSO is mandatory to push the confidence building “between both banks of the Diester River”. This cooperation has some clear benefits, as it enhances the interpersonal links between CSOs representatives, and enables knowledge exchange not only at the local scale but also at the more international scale (e.g. study visits in third countries). However, there are also some drawbacks, as the Moldovan-based CSO is often instrumental for the Transnistrian one to get funds. Some Transnistrian CSOs having the resources and knowledge to navigate the de facto border, create a mirror entity registered in the Moldovan-controlled territory to mitigate the different currency and banking systems between Transnistria and the Moldovan-controlled territory. As no direct banking transfer is possible from Chisinau-based donors to Transnistrian CSOs, the de facto border constitutes a hard obstacle to financial flows. In the transfer process, CSOs lose the exchange rate between the Moldovan Lei and the Transnistrian Rubble and have to pay a “management fee” to the Moldova-registered CSO processing the transfer (interview 2). This decreases their resources to provide social services and makes some Transnistrian CSOs leaders feel like “second-class citizens” (interview 22). Some CSOs representatives argue that international donors and organizations favor a double-standard approach and see such discrimination as contradicting the equal treatment and universal values that international donors and organizations are meant to promote. However, donors argue that for accountability reasons they are unable to transfer directly funds to a Transnistrian entity (interview 17).

Another result of the de facto border making is the existence of roaming fees for calls between the Moldovan-controlled territory and Transnistria as a result of different phone dials on both sides of the de facto border. This impacts, for example, the operation of hotlines supporting (potential) victims of domestic violence and human trafficking. It was also the object of negotiations between donors and a Transnistrian CSO operating the hotline. In the loop of engagement, feedback and reengagement (Batley and Rose Citation2011) to overcome the effect of the de facto border in service provision, eventually a hotline was established with the Transnistrian phone dial. This example shows the agency that CSOs retain in their feedback and reengagement with international donors to address the de facto border’s impact on social services provision.

Abkhazian CSOs – Georgian authorities

As in the case of Transnistrian CSOs, Abkhazian CSOs have no direct collaboration with Georgian authorities and the collaboration is mediated through Georgian CSOs. Despite a certain defiance toward Georgia, partnerships between Georgian and Abkhazian CSOs exist and technical cooperation and people-to-people contacts occur. This is often the case within the framework of initiatives such as COBERM supported by international donors and organizations. In these cross-border engagements, particular attention is paid to the wording of the project and its implementation framework, not only to obtain the participation of the Abkhazian CSOs but also to not endanger the Abkhazian CSOs vis-à-vis local authorities.

In some cases, Abkhazian CSOs prefer to relinquish international donors’ funds rather than to compromise on what they perceive as their core values and raison d’être (e.g. not being named as “a Georgian NGO”, or “part of Georgia”). What is more, as expressed by a staff member of an Abkhazian CSO, several Abkhazian CSO representatives interviewed favor a direct relationship with representatives of international donors and organizations, rejecting the mediation of Georgian authorities and CSOs:

Quite often international organisations want to put their activities under the prism of conflict transformation and confidence building where some kind of collaboration with Georgian NGOs is needed. Our position is the following: we believe that dialogue is important, and we are involved in it, but we think that it’s a different format and that there are things that should not be attached to the confidence building with Georgia. We also have the right to the democratic development of society. [International organisations] are doing a lot, but this approach causes a negative reaction and suspicion among the society.

The firm position of Abkhazian CSOs reduces to some extent their access to (financial) resources across the de facto border, but it enables these CSOs to maintain trust with their constituency vis-à-vis the Abkhazian authorities. As in the case of Transnistria, the de facto border is a strong obstacle to the financial flows from international donors to Abkhazian CSOs. The Russian Ruble is used in Abkhazia and Abkhazian CSOs used to receive international funds through Russian banks, but the EU sanctions on Russia following Russia’s full-scale war in Ukraine impact financial flows to Abkhazia and CSOs in particular. Banking transfers from international donors and organizations based in Georgia are now sent to Abkhazian CSOs through Armenia, resulting in greater losses with the exchange and transfer fee. It remains to be seen how the EU-Russia confrontation over Ukraine will impact the trajectory of European funds allocated to Abkhazian and Transnistrian CSOs, in particular to those providing social services. Already, this confrontation shapes the feedback and reengagement between all the actors involved in social services provision in Abkhazia and Transnistria.

Conclusion

This article has explored how in the field of social services provision by CSOs in Transnistria and Abkhazia, de facto borders and bordering practices are materializing and negotiated in a triangulated relationship of relevant actors. The impact of the de facto borders and bordering practices on the activities of CSOs as crucial actors providing social services in the de facto states is tangible across the different scales. At the local scale, legal boundaries shape the space available and the margin of action for CSOs providing social services in Transnistria and Abkhazia. The most tangible impact of these legal boundaries results in the (in)capacity of Abkhazian and Transnistrian CSOs to navigate across the de facto border, especially to mobilize (financial) resources from international donors and organizations. Besides the impact of these legal boundaries, the external contacts of CSOs raise suspicion from the de facto authorities, making the de facto borders and bordering practices more tangible and shaping the space where CSOs can provide social services. At the local scale, CSOs keep engaging with the de facto authorities in a loop of engagement, feedback, and reengagement, to make the de facto border more porous to international (financial) resources and address societal taboos, such as gender-based and domestic violence. This negotiation is facilitated in the Abkhazian context by the tied kin-linkage in a small-sized society. Yet, the cooperation between the Moldovan and Transnistrian authorities is more fluid than the one between the Georgian and Abkhazian ones. This leads to a more porous de facto border, including for international donors and organizations, and easier provision of social services. In both contexts, Abkhazian and Transnistrian authorities need local CSOs to provide and upgrade social services and are thus to some extent more lenient in their approach, allowing passages of the de facto border and mitigation of bordering practices.

At the regional scale, Georgia and Moldova keep denying the existence of a de facto border, although their national police forces make it more tangible by checking documents (Georgia) and as their customs officers stand at the de facto border (Moldova). Both authorities have set up strategies of Confidence Building Measure (Moldova/Transnistria) and COBERM (Georgia/Abkhazia) with the impulse of international donors and organizations. The latter is balancing between the willingness to engage with Transnistria and Abkhazia and the constraints of nonrecognition policies adopted by Moldova and Georgia. Transnistrian and Abkhazian CSOs remain the main vehicles of international donors and organizations’ engagement, as no official relationship is possible with both de facto authorities even when it comes to social services provision.

At an international scale, Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has reactivated the geopolitical saliency of the Abkhazian and Transnistrian de facto borders. Illegalized crossings to the Georgian-controlled territory have increased following Putin’s declaration of a “partial mobilisation” across Russia on 21 September 2022. International donors and organizations keep engaging with both Abkhazia and Transnistria through CSOs in the field of social services provision, as they are well aware that disengagement will strengthen the isolation of both de facto states, giving Russia more leeway, including via support to social services. The current pro-European orientation of the governments in Moldova and at least facially in Georgia has further impacted cross-border interactions, with Moldova granted candidate status by the EU in 2022 and Georgia in 2023.

Given the exploratory nature of this research, it is only a first step in the study of the de facto borders’ impact on the functioning of CSOs in de facto states, and how these organizations navigate the complex geopolitical landscape. Our findings offer an important basis for more theoretically driven and methodologically different research into how de facto border making and border practices affect the activities of CSOs as crucial actors providing social services, not only in Transnistria and Abkhazia, but also in other de facto states in the post-socialist region and beyond.

This research also offers interesting research avenues into the dynamics of the Zugdidi-Gal(i) borderland in social services provision, in particular for social services, such as support to survivors of gender-based and domestic violence, as this service is rooted in the geopolitical confrontation between Russia and the “West”. If de facto borders hamper social services provision in Abkhazia and Transnistria, they may also foster it on the Georgian and Moldovan-controlled side as closely as possible to the Transnistrian and Abkhazian-controlled territory, in a willingness to keep social ties with Abkhazia and Transnistrian inhabitants. Studying the impact of de facto borders on social service provision could also be enriched by focusing on the perspectives of social services’ beneficiaries to analyze how they navigate across the de facto borders to access social services, which constraints they face and which strategies they put in place.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Tamar Zviadadze, intern at the United Nations University (CRIS), for her valuable support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. In this paper, international organizations are understood as a legal body created by treaties between states and operating within the framework of international law.

2. The choice was made before 24 February 2022 when Russia’s large-scale war in Ukraine started and changed the situation regarding safety in Transnistria and, to some extent, in Abkhazia.

3. Закон о некоммерческих организациях (НКО) accessible in Russian at http://president.gospmr.org/pravovye-akty/zakoni/zakon-pridnestrovskoy-moldavskoy-respubliki-o-nekommercheskih-organizatsiyah-.html Article 2, paragraph 7: “Некоммерческой организации, получающей денежные средства и иное имущество от иностранных государств, (…) зарегистрированных на территории Приднестровской Молдавской Республики, (…), запрещается участвовать, в том числе в интересах иностранных источников, в политической деятельности, осуществляемой на территории Приднестровской Молдавской Республики”. Own translation: “A non-profit organisation receiving funds and other property from foreign countries, (…) registered in the territory of the Transnistrian Moldovan Republic, (…) shall be prohibited from participating, including for the benefit of foreign sources, in political activities carried out in the territory of the Transnistrian Moldovan Republic”.

4. Закон Приднестровской Молдавской Республики «О противодействии экстремистской деятельности» accessible in Russian here http://www.vspmr.org/legislation/laws/zakonodateljnie-akti-pridnestrovskoy-moldavskoy-respubliki-v-sfere-obrazovaniya-kuljturi-sporta-molodejnoy-politiki-sredstv-massovoy-informatsii-a-takje-v-sfere-realizatsii-politicheskih-prav-i-svobod-grajdan/zakon-pridnestrovskoy-moldavskoy-respubliki-o-protivodeystvii-ekstremistskoy-deyateljnosti.html.

5. Official information agency of Transnistria – Информационное агентство “новостеи Приднестровья” С 15 февраля по 31 марта в ПМР пройдёт конкурс на президентские гранты – From 15 February to 31 March, Transnistria will hold a competition for presidential grants published February 03, 2021. – Accessed January 21, 2022 https://novostipmr.com/ru/news/21-02-03/s-15-fevralya-po-31-marta-v-pmr-proydyot-konkurs-na-prezidentskie.

6. Федеральный закон от 20.07.2012 N 121-ФЗ (ред. от 04.06.2014) “О внесении изменений в отдельные законодательные акты Российской Федерации в части регулирования деятельности некоммерческих организаций, выполняющих функции иностранного агента” – Federal Law of July 20, 2012 N 121-FZ (revised on June 4, 2014) “On Amendments to Certain Legislative Acts of the Russian Federation Regarding Regulation of Activities of Non-Profit Organisations Performing the Functions of a Foreign Agent. (All English versions are our own translations).

Федеральный закон от 14 июля 2022 г. N 255-ФЗ “О контроле за деятельностью лиц, находящихся под иностранным влиянием” (с изменениями и дополнениями) “On control over the activities of persons under foreign influence” (as amended and supplemented), accessible here: https://base.garant.ru/404991865/.

7. See in particular point 37, accessible in Russian here http://presidentofabkhazia.org/upload/iblock/dc5/programma-_1_.pdf – Разработка и подписание меморандума и планаграфика приведения законодательства Республики Абхазия в соответствие с законодательством Российской Федерации, регулирующим деятельность некоммерческих организаций и иностранных агентов” – “Develop and sign a memorandum and timeline to bring the legislation of the Republic of Abkhazia regulating non-profit organisations and foreign agents in line with the legislation in force in the Russian Federation.”

8. See Law of Georgia On Elimination of Domestic Violence, Protection and Support of Victims of Domestic Violence (May 26, 2006) accessible here: https://matsne.gov.ge/en/document/view/26422?publication=18.

9. See Russian press agencies Interfax: https://www.interfax.ru/world/861812 and TASS https://tass.ru/mezhdunarodnaya-panorama/15729691?utm_source=google.com&utm_medium=organic&utm_campaign=google.com&utm_referrer=google.com.

10. Верховный Cовет Приднестровской Молдавской Республики/Supreme Council of the Transdniestrian Moldovan Republic: http://www.vspmr.org/news/supreme-council/15-let-referendumu-o-nezavisimosti-pridnestrovjya-i-vhojdenii-v-sostav-rf.html − 15 лет референдуму о независимости Приднестровья и вхождении в состав РФ/15 years of the referendum on Transnistrian independence and accession to the Russian Federation – Published September 17, 2021 – Accessed September 10, 2022.

11. Law accessible in English here: https://matsne.gov.ge/en/document/view/19132?publication=6 – see article 6.

References

- Anderson, Malcolm. 2013. Frontiers: Territory and State Formation in the Modern World. Routledge.

- Babajanian, Babken, Sabine Freizer, and Daniel Stevens. 2005. “Introduction: Civil Society in Central Asia and the Caucasus.” Central Asian Survey 24 (3): 209–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/02634930500310287.

- Bakradze, David.2018. “Russia’s Occupation of Georgia and the Erosion of the International Order.” https://www.csce.gov/international-impact/events/russias-occupation-georgia-and-erosion-international-order.

- Batley, Richard, and Pauline Rose. 2011. “Analysing Collaboration Between Non‐Governmental Service Providers and Governments.” Public Administration and Development 31 (4): 230–239. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.613.

- Blakkisrud, Helge, Nino Kemoklidze, Tamta Gelashvili, and Pål Kolstø. 2021. “Navigating de Facto Statehood: Trade, Trust, and Agency in Abkhazia’s External Economic Relations.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 62 (3): 347–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/15387216.2020.1861957.

- Blakkisrud, Helge, and Pål Kolstø. 2011. “From Secessionist Conflict Toward a Functioning State: Processes of State-and Nation-Building in Transnistria.” Post-Soviet Affairs 27 (2): 178–210. https://doi.org/10.2747/1060-586X.27.2.178.

- Bürkner, Hans-Joachim, and James W. Scott. 2019. “Spatial Imaginaries and Selective In/Visibility: Mediterranean Neighbourhood and the European Union’s Engagement with Civil Society After the ‘Arab Spring’.” European Urban and Regional Studies 26 (1): 22–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776418771435.

- Cammett, Melani Claire, and Lauren M. MacLean. 2011. “Introduction: The Political Consequences of Non-State Social Welfare in the Global South.” Studies in Comparative International Development 46 (1): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-010-9083-7.

- Caspersen, Nina. 2009. “Playing the Recognition Game: External Actors and de Facto States.” The International Spectator 44 (4): 47–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/03932720903351146.

- Cole, Mike. 2020. Theresa May, the Hostile Environment and Public Pedagogies of Hate and Threat. London: Routledge.

- De Tinguy, Anne. 2009. “La Russie et Ses Frontières, Vingt Ans Après l’éclatement de l’empire Soviétique.” Dossiers Du CERI, 1–9.

- Elman, Colin, John Gerring, and James Mahoney. 2020. The Production of Knowledge: Enhancing Progress in Social Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Esiava, B. 2019. “Первые рубежи: как борются с туберкулезом в Абхазии.” Sputnik/abkhaz, March 22, 2019. https://sputnik-abkhazia.ru/Abkhazia/20190322/1026930432/Pervyerubezhi-kak-boryutsya-s-tuberkulezom-v-Abkhazii-.html.

- European Union External Action. 2017. “Statement on the Latest Developments Along the Administrative Boundary Line of Georgia’s Breakaway Region of Abkhazia.” February 25. https://www.eeas.europa.eu/node/21406_en.

- Ganohariti, Ramesh. 2020. “Dual Citizenship in ‘de Facto’ States: Comparative Case Study of Abkhazia and Transnistria.” Nationalities Papers 48 (1): 175–192. https://doi.org/10.1017/nps.2018.80.

- Harzl, Benedikt. 2018. The Law and Politics of Engaging ‘de Facto’ States: Injecting New Ideas for an Enhanced EU Role. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

- Kolossov, Vladimir. 2005. “Border Studies: Changing Perspectives and Theoretical Approaches.” Geopolitics 10 (4): 606–632. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650040500318415.

- Kolossov, Vladimir, and John O’Loughlin. 2011. “After the Wars in the South Caucasus State of Georgia: Economic Insecurities and Migration in the” ‘de Facto’ ”States of Abkhazia and South Ossetia.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 52 (5): 631–654.

- Kotova, Marianna, and Salome Partzvania. 2021. “Is Georgian Language Banned in Abkhaz Schools?” May 11. https://jam-news.net/is-georgian-language-banned-in-abkhaz-schools/.

- Le Pavic, Gaëlle, Tamar Zviadaze, Giacomo Orsini, and Ine Lietaert. 2022. Providing Welfare Service within and Across Contested Borders: The Activities of Civil Society Organisations in Transnistria and Abkhazia. Bruges: United Nation University (CRIS) – Working Paper Series UNU-CRIS.

- Mezzadra, Sandro, and Brett Neilson. 2013. “Border as Method, Or, the Multiplication of Labor.” In Border as Method, Or, the Multiplication of Labor. Duke: Duke University Press.

- “Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States.” 1933. https://www.ilsa.org/Jessup/Jessup15/Montevideo%20Convention.pdf.

- Newman, David, and Anssi Paasi. 1998. “Fences and Neighbours in the Postmodern World: Boundary Narratives in Political Geography.” Progress in Human Geography 22 (2): 186–207. https://doi.org/10.1191/030913298666039113.

- Óbeacháin, Donnacha, Giorgio Comai, and Ann Tsurtsumia-Zurabashvili. 2016. “The Secret Lives of Unrecognised States: Internal Dynamics, External Relations, and Counter-Recognition Strategies.” Small Wars & Insurgencies 27 (3): 440–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/09592318.2016.1151654.

- O’Loughlin, John, Vladimir Kolossov, Gerard Toal, and Gearóid Tuathail. 2011. “Inside Abkhazia: Survey of Attitudes in a de Facto State.” Post-Soviet Affairs 27 (1): 1–36. https://doi.org/10.2747/1060-586X.27.1.1.

- Orsini, Giacomo, Andrew Canessa, and Luís Martínez. 2018. Barrier and Bridge: Spanish and Gibraltarian Perspectives on Their Border, edited by Andrew. Canessa, 22–43. Canñada Blanch/Sussex Academic studies on contemporary Spain. Brighton: Sussex Academic Press.

- Orsini, Giacomo, Andrew Canessa, Luis Gonzaga Martínez del Campo, and Jennifer Ballantine Pereira. 2019. “Fixed Lines, Permanent Transitions. International Borders, Cross-Border Communities and the Transforming Experience of Otherness.” Journal of Borderlands Studies 34 (3): 361–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2017.1344105.

- Pegg, Scott. 1998. International Society and the ‘de Facto’ State. New edition 2021. Routledge.

- Popescu, Nicu. 2010. EU Foreign Policy and Post-Soviet Conflicts: Stealth Intervention. Routledge.

- Shevtsova, Maryna. 2022. “Religion, Nation, State, and Anti-Gender Politics in Georgia and Ukraine.” Problems of Post-Communism 70 (2): 163–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/10758216.2022.2085581.

- State Security Service of Georgia. 2021. “Statement of the State Security Service of Georgia.” https://ssg.gov.ge/en/news/677/saxelmtsifo-usafrtxoebis-samsaxuris-gancxadeba.

- UNDP. 2016. “[Closed] Contribution to the Confidence Building Measures Programme in Transnistria Region – Health Sector (Phase 2).” Activity Report. https://www.undp.org/moldova/projects/closed-contribution-confidence-building-measures-programme-transnistria-region-health-sector-phase-2.

- UNDP. 2018. “European Union Confidence Building Measures Programme V.” https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/migration/md/b554bb353ca0750604cd4b8dda7c83dcaa2ef2f2c21c21fe4dbc2dd925075ace.pdf.

- UNICEF Georgia. 2020. “UNICEF Georgia COVID-19 Situation Report.” July 3. https://www.unicef.org/media/81691/file/Georgia-COVID19-SitRep-3-July-2020.pdf.

- Yuval-Davis, Nira. 2013a. “A Situated Intersectional Everyday Approach to the Study of Bordering.” Euborder-Scapes Working Paper, no. 2.

- Yuval-Davis, Nira. 2013b. “A Situated Intersectional Everyday Approach to the Study of Bordering.” Euborder-Scapes Working Paper 2.

- Yuval-Davis, Nira, Georgie Wemyss, and Kathryn Cassidy. 2017. “Introduction to the Special Issue: Racialized Bordering Discourses on European Roma.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 40 (7): 1047–1057. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2017.1267382.