ABSTRACT

A growing body of research focuses on individual environmental consciousness as an alternative and complement to regulatory and economic policy strategies for sustainable development. However, existing studies failed to explain the complex associations between individual environmental consciousness and conservation practices. This study constructs a framework of environmental prefigurative politics - technologies of the self (EPP-TS) to investigate how the mobilization of technologies of the self can lead to the subjectivization of individual environmental consciousness, thus enabling environmental prefigurative politics to shape specific conservation practices. First, this study argues that a range of technologies of the self, including discursive, incentive, and disciplinary technologies, are mobilized to subjectivize individual environmental consciousness. Second, the subjectivization of individual environmental consciousness prompts and institutionalizes the improvisation of environmental prefigurations, embodying the political imaginaries and power structures that environmental prefigurative politics aspire to realize in society. Third, environmental prefigurative politics also influence the development pathways and situated agency of nature conservation, thereby shaping specific conservation practices. Finally, this study also critiques the environmental prefigurative politics under authoritarian environmentalism, as it also reinforces authoritarian power in subjectivizing individual environmental consciousness.

Introduction

A growing body of research focuses on individual environmental consciousness as an alternative and complement to regulatory and economic policy strategies for sustainable development (Bell Citation2005). Environmental consciousness means that individuals will consciously and voluntarily adopt pro-environmental behaviors “by which men not only set themselves rules of conduct, but also seek to transform themselves” (Foucault Citation1990, 10). However, how does individual environmental consciousness arise? What unites many individuals at a deeper level in support of nature conservation? And how do individual environmental consciousnesses shape specific conservation practices? Surprisingly, these complexly entangled questions of environmental consciousness and conservation practices have received relatively little attention among critical geographers and political ecologists, especially compared to their large and rich body of research on neoliberal environmentality (Fletcher Citation2010). In searching for answers to these questions, recent research suggests that the reconceptualization of individual environmental consciousness involves a series of environmental prefigurative politics (Mason Citation2014). These prefigurative politics stimulate the imagination as it reconfigures lived social relations and the exercise of power in the search to realize desired visions (Monticelli Citation2021).

Despite the rapid rise of research on prefigurative politics (Jeffrey and Dyson Citation2021), there is a paucity of research into people’s environmental efforts to imagine different futures. Most studies have focused on defining the concept of prefigurative politics, applying it to specific cases, or categorizing various types of prefigurative strategies (Törnberg Citation2021). Research on prefigurative politics has largely come from actual studies of movements that engage in, and to some extent consciously identify with, prefigurative practices (Swain Citation2019). Especially in recent years, prefigurative politics has been widely used in the study of alternative globalization and the Occupy movement (Gordon Citation2008). For instance, the feminist movement, which has proliferated in recent years, has sought to use prefigurative action to effect change (Jeffrey and Dyson Citation2021). While these empirical studies have revealed much about the practical dilemmas and problems involved in such movements, critical analysis of environmental issues has received little attention. Only limited literature has focused on the impact of anticipatory politics on conservation practices (Han and Sheng Citation2023). However, existing research on anticipatory politics fails to explain the rationality of individuals taking conservation actions in the present for the sake of future environmental visions.

This study seeks to advance the understanding of the complex linkages between environmental consciousness and conservation practices in order to contribute theoretically and empirically to a deeper understanding of the role of environmental prefigurative politics in shaping individual conservation practices. Environmental prefigurative politics is essentially the way in which environmental activists and environmental movements attempt to create and embody the ecological values and conservation practices they advocate in their daily lives and actions. It is based on the idea that the means of social change should be aligned with the desired ends, and that by living according to alternative ecological principles, activists can challenge the dominant environmental paradigm and inspire others to join them. Therefore, this study argues that tracing the notion of “technologies of the self” in Foucaultian thought can fruitfully illuminate the complexity of environmental prefigurative practices in shaping individual conservation practices. This requires a focus on the rationality and strategy of individuals’ adoption of conservation practices, as well as the spatial and temporal complexity of their behavior within environmental prefigurative practices. Therefore, this study builds on the progressively growing body of research on technologies of the self (Elshimi Citation2015; Hanna Citation2013) by substantively focusing on the ways in which environmental prefigurative politics mobilizes technologies of the self for the subjectivization of individual environmental consciousness. The process of subjectivization is the categorization of specific behaviors, or in this study, typical behaviors of an individual self’s environmental protection practices. Individuals will have subjectivity due to performing the process of subjectivization on themselves (Foucault Citation2017). Subjectivity is a permanent relationship between an individual and his or her self, which is then internalized and projected as others (Foucault Citation2017). By calling for a shift in critical studies from subjection to active subjectivization (Foucault Citation1988b), this study advances the understanding of how environmental prefigurative politics shapes conservation practices.

This study aims to scrutinize the processes by which environmental prefigurative politics shape conservation practices through the lens of technologies of the self. As such, this study correlates existing research on prefigurative politics (Gordon Citation2018; Jeffrey and Dyson Citation2021; Swain Citation2019) with Foucaultian literature on technologies of the self (Foucault Citation1988b, Citation1990; Foucault et al. Citation1991) to develop a framework of environmental prefigurative politics – technologies of the self (EPP-TS). This study then employs this framework to examine the case of China’s Qingshan Village to explore how individual environmental consciousness can be subjectivized by mobilizing technologies of the self so that environmental prefigurative politics can shape concrete conservation practices. Through a combination of content analysis, semi-structured interviews, and participant observation, this study first argues that a range of technologies of the self, including discursive, incentive, and disciplinary technologies, are mobilized to subjectivize individual environmental consciousness. Second, the subjectivization of individual environmental consciousness prompts and institutionalizes the improvisation of environmental prefigurations, embodying the political imaginaries and power structures that environmental prefigurative politics aspire to realize in society. Third, environmental prefigurative politics also influence the development pathways and situated agency of nature conservation, thereby shaping specific conservation practices. Finally, this study also critiques the environmental prefigurative politics under authoritarian environmentalism, as it also reinforces authoritarian power in subjectivizing individual environmental consciousness.

Empirically, as one of the first investigations of Qingshan Village, this study adds to the limited research on prefigurative politics in China’s socio-economic context (Fu Citation2019). In addition, this study also contributes more empirical analysis and evidence to the limited research on environmental prefigurative politics (Han and Sheng Citation2023). Theoretically, by exploring the complex associations between individual environmental consciousness and conservation practices in China’s Qingshan Village, this study contributes to the literature examining environmental prefigurative politics from a perspective of technologies of the self. Although there has been a rich body of research on either prefigurative politics or technologies of the self, no study has yet paid attention to the possible connection between the two. The EPP-TS analytical framework proposed in this study combines research on the environmental prefigurative politics with analysis of technologies of the self, providing a viable conceptual framework for examining the subjectivization of individual environmental consciousness and the process by which environmental prefigurative politics shapes conservation practice from the perspective of technologies of the self.

Environmental prefigurative politics and technologies of the self: an analytical framework

As noted in the previous section, it is problematic to characterize or explain individual environmental consciousness and the dynamics of conservation practices through a traditional framework of prefigurative politics. This section will combine environmental prefigurative politics and technologies of the self to develop an analytical framework for examining the complex connections between individual environmental consciousness and conservation practices.

Environmental prefigurative politics

Environmental prefigurative politics attempts to realize political ideas and power structures in nature conservation. Derived from the Latin word “praefigurare”, which itself literally means something that will happen in the future, Boggs (Citation1977) used the term to describe the forms of social relations, decision-making, culture, and human experience that embody the ultimate goals in the movement’s ongoing political practices. Environmental prefigurative politics reflects the ways in which people organize, design, and practice to formulate visions of nature conservation and promote them as the imminent or more distant future. Thus, environmental prefigurative politics is the most fundamental politics that would seek to realize an ideal vision of nature conservation by stimulating the imagination while reconfiguring social relations and exercising power (Brissette Citation2016). In contrast to anticipatory politics, which advocates focusing on present conservation rather than intervening in dangerous futures, environmental prefigurative politics seeks to simultaneously transform the present to address existing environmental crises as well as manage possible future environmental threats (Jeffrey and Dyson Citation2021). These environmental prefigurative politics can consciously channel individuals into action for nature conservation and be generalized in a future characterized by power, hierarchy, and conflict.

Environmental prefigurative politics seeks to open up space for visions of nature conservation in the present. This means that environmental prefigurative politics abstracts temporal meanings from it in order to theorize goals in terms of current values rather than potential future social states (Gordon Citation2018). As Milstein (Citation2000) argued, rather than deferring the ideal society to the distant future, environmental prefigurative politics seeks to directly connect current conservation practices to possible futures in order to carve out space in the present. Thus, environmental prefigurative politics tends to build on the idea that the future will be different from the present, making the future more sustainable and inclusive through spatial processes, material engagements, and concrete conservation practices in the present.

Improvisation aimed at pursuing current conservation actions constitutes a critical element of environmental prefigurative politics. Prefigurative politics typically emphasizes concrete actions, as these actions, which bring about change by actively engaging with the world, represent utopian visions in themselves (Graeber Citation2009). Similarly, environmental prefigurative politics also emphasizes immediately implemented direct actions that enable groups or individuals to use their power to prevent environmental degradation or provide ecological goods without resorting to external agents (Gordon Citation2018). Thus, utopian visions of nature conservation correspond not to fantasies, but to hopes and actions, which allow individuals to act in the present along with their hopes (Gordon Citation2018). These actions for nature conservation are usually practices that are inconsistent with the individual’s environment or prior experience. If anticipatory politics is an instance of individuals devoting their energies to shaping a desired future, environmental prefigurative politics is a stark contrast between anticipated and existing nature through bold and forward-thinking conservation practices (Jeffrey and Dyson Citation2021).

Another critical element in environmental prefigurative politics is the institutionalization of conservation actions in the present. Environmental prefigurative politics embodies alternative forms of social relations, decision-making, culture, belief systems, and direct experience in nature conservation (Monticelli Citation2021). These alternative forms reinforce and perpetuate the prefigurative politics of conservation action through institutionalization. A range of institutions and technologies emerge from this institutionalization that aims to integrate current conservation action into broader thought processes through alternative futures (Jeffrey and Dyson Citation2021). For instance, Han and Sheng (Citation2023), in their study of China’s Great Yangtze River Protection Programme, describe China’s institutionalization of an ecological civilization imaginary for the future into the country’s environmental policy framework and official ideology. This institutionalization of environmental prefigurative politics provides legitimacy to the regime’s conservation actions in the present and allows the regime to derive authority to exercise power from it (Sheng, Ding, and Han Citation2022).

Ultimately, environmental prefigurative politics can change the development pathways and situated agency of nature conservation, thereby shaping the specific conservation practice. Jeffrey and Dyson (Citation2021) argued that prefigurative politics could have an impact in four ways: (i) by leading to the expansion of initiatives; (ii) by creating enduring skills, knowledge, or resources; (iii) by eliciting attitudinal changes; and (iv) by generating emotional importance. Similar impacts occur in environmental prefigurative politics, which can alter the development pathways and situated agency of nature conservation (Shapiro-Garza et al. Citation2020). Development pathways that include economic, environmental, and political contexts, as well as local institutional, social, and cultural norms, can explicitly shape specific forms of conservation practice (Bétrisey, Bastiaensen, and Mager Citation2018). Local actors consciously or unconsciously reshape existing and create new situated agencies, including institutional arrangements, norms, and power relations in response to new knowledge and changing influences of environmental prefigurative politics (Kolinjivadi et al. Citation2019). Thus, the influence of environmental prefigurative politics determines conservation practices.

However, the theory of environmental prefigurative politics does not clearly explain why and how individuals take conservation action in the present for the sake of future visions. Jeffrey and Dyson (Citation2021) argued that prefigurative politics would be carried out through an intensive commitment to improvising existing ideas, materials, spaces, bodies, and emotional states. However, why individuals in prefigurative politics act on these improvisations or utopian visions remains unclear. To this end, this study draws on the Foucaultian notion of “technologies of the self” to understand this transformation of the individual, which focuses on the practice of subjectivization, i.e. the subject’s practice of the self and the other (Asiyanbi, Ogar, and Akintoye Citation2019). This study seeks to integrate the theories of environmental prefigurative politics and technologies of the self into a new analytical framework that can be used to explain how environmental prefigurative politics, through technologies of the self, can effect a transformation of the individual into one who is willing to take conservation action in the present for the sake of an environmental vision of the future.

Technologies of the self

The focus on technologies of power obscures the role of technologies of the self. Spinoza divided power into potestas and potentia: the former separates something from what it can do through domination or exploitation, while the latter is an inherent capacity to act (Ruddick Citation2010). In the Foucaultian framework, these two kinds of power are expressed as “technologies of power” and “technologies of the self”. The former is conceptualized by Foucault as governmentality, reflecting the engagement between technologies of domination over others and technologies of self-rule (Foucault et al. Citation1991). Its reflection of the relationship between people concerns the governance of “conduct of conducts” (Huxley Citation2008). However, a great deal of existing research on governmentality prioritizes technologies of power and pays insufficient attention to techniques of the self. This is a common flaw in many applications of the ideas on governmentality, largely due to the disjointed integration of Foucault’s ideas on governmentality with his earlier work on the concepts of power and obedience (Singh Citation2013). Foucault himself recognized that his early work insisted too much on the technologies of domination and power, and that his later work dealt more with the technologies of the self (Foucault Citation1988b).

Technologies of the self are related to subjectivization and focus on moving from obedience to subjectivity. Foucault (Citation1988b) defined technologies of the self as a certain amount of manipulation of one’s body, soul, thoughts, behaviors, and ways of being by the individual, either on his or her own or with the help of others, in order to change him or her. This suggests that the realization of technologies of the self is the process of shaping the self through what one believes to be the truth (Milchman and Alan Citation2009). Thus, the key to technologies of the self lies in the shift from passive obedience to active subjectivization and how the subject resolves strategic decisions and localized antagonisms in the pursuit of diverse new relationships (Foucault Citation1988b). Foucault (Citation1990) argued that technologies of the self aimed at subjectivization are co-constituted by four elements: ethical substance, modes of subjection, forms of elaboration, and telos. Ethical substance is the part of one’s self that is identified as the focal point of one’s moral behavior. Modes of subjection are the relationships that a person establishes between himself or herself and the rules of behavior. Forms of elaboration are changes in behavior or thought in order to bring one’s self into compliance with the rules. Finally, telos involves integrating this behavior into a broader pattern of behavior. Technologies of the self, therefore, require multiple practices and different goals – body, soul, mind, behavior, and ways of being (Asiyanbi, Ogar, and Akintoye Citation2019).

Environmental prefigurative politics needs to motivate and institutionalize the transformation of individuals into subjects pursuing current conservation actions, thus subjectivizing individual environmental consciousness. Realizing political ideologies and power structures in nature conservation relies on individuals identifying with visions of the future and seeing them as truths, thereby transforming the subject into the self (Foucault Citation1988b). The transformation of the passive individual into a subject is the result of power effects, where the power-producing subject is not merely fictionalized by theory and law, but genuinely created by human activity (Elshimi Citation2015). In environmental prefigurative politics, the subjectivization of environmental consciousness relies on various technologies that shape the self in the current society. As Rose (Citation2011) argued, the human experience of the self – the creation of freedom, personal power, and self-actualization – results from various human technologies that take the human model as their object. These human technologies have led the subject to think and realize that the vision of nature conservation has become truthful by its recognition, and this has led to the birth of environmental consciousness (Levinas Citation2000). This environmental consciousness allows the subject to embody responsibility for nature conservation in limiting itself while making itself the object of understanding and attention (Bergen and Verbeek Citation2021). In this sense, environmental consciousness has been internalized as truth in subjectivization and has become the medium and object through which individuals deal with their relationships with themselves, with others, and with the environment (Legg Citation2016).

Environmental prefigurative politics relies on a combination of technologies of the self. In environmental prefigurative politics, technologies of the self that are transformed from the individual to the subject are derived from analyses of techniques of self-formation, i.e. specific techniques that humans use to make sense of themselves (Foucault Citation1988b). Elshimi (Citation2015), in the study of de-radicalization interventions, understands de-radicalization as a technology of the self and further discusses the interplay between the three main technologies of the self: discursive, disciplinary, and confessional. In addition, incentives also drive the process of individuals moving from obedience to subjectivity in nature conservation (Asiyanbi, Ogar, and Akintoye Citation2019), reflecting a particular kind of neoliberal environmentality (McGregor et al. Citation2015). Given the importance of incentives in Foucaultian technologies of the self, this study enumerates the technologies of the self in nature conservation in three domains, including discoursive, disciplinary, and incentive technologies. Discursive technologies are able to shape future visions of nature conservation into concrete discourses, creating a desired regularity for the subject and making the discourse intelligible within environmental prefigurative politics. Incentive technologies are designed to channel individual subjectivization within environmental prefigurative politics by creating external incentives for individuals as rational actors to exhibit appropriate behaviors. Disciplinary technologies are ways in which institutions, interventions, and programmatic rationality work and operate together to create obedient subjects in environmental prefigurative politics.

It is worth noting that incentive technologies may also exist outside the neoliberal context. As a typical incentive technology, payments for ecosystem services (PES) in neoliberal systems use economic incentives to manage ecosystems (Farley and Costanza Citation2010). However, this incentive technology is not unique to neoliberal contexts and is also found in authoritarian systems. As demonstrated by Sheng and Han (Citation2022a), to promote the application of PES in China, the central government used an incentive technology called cadre promotion tournaments to encourage local officials to pay more attention to ecosystem conservation. Specifically, as the performance of ecosystem conservation is included in officials’ performance appraisal, officials will shift from obedience to subjectivity in such cadre promotion tournaments in order to gain promotions in their positions (Sheng, Webber, and Han Citation2018). However, cadre promotion tournaments as incentive technologies also contain elements of disciplinary technologies. These are also internalized by officials in bidding tournaments in the form of self-regulation because they are aware of being appraised and observed, and control their own behavior based on normative appraisals (Foucault Citation2023). Promotion tournaments targeting ecosystem conservation combine a centralized personnel control system with decentralized local administrative power, reflecting the typical characteristics of authoritarian regimes (Sheng, Webber, and Han Citation2018).

However, subjectivization, especially under authoritarian environmentalism, has been widely criticized from a moral perspective. As Y. Li and Shapiro (Citation2020) observed, rather than viewing environmentalism as a goal for action, the Chinese state consolidates its power over territories and individuals by expanding its regulatory reach into the environmental sphere and incorporating non-state actors into the state’s environmental agenda. Similarly, Rodenbiker (Citation2023) argued that China’s eco-developmentalism, constructed by combining ecological and state power, has triggered displacement and inequitable outcomes in the countryside, and that its reinforcement of authoritarian power provides a cautionary tale for the rest of the world. Unlike authoritarian environmentalism, which advocates for increased regulatory power over individuals, Ostrom (Citation2015) advocates a vision of cooperative behavior that does not depend on a centralized state of power, which allows models of decentralization and incentive-based local resource governance to be replicated in different contexts. Ostrom’s perspective thus offers the prospect of solutions to the ecological damage caused by unregulated economic development (Forsyth and Johnson Citation2014).

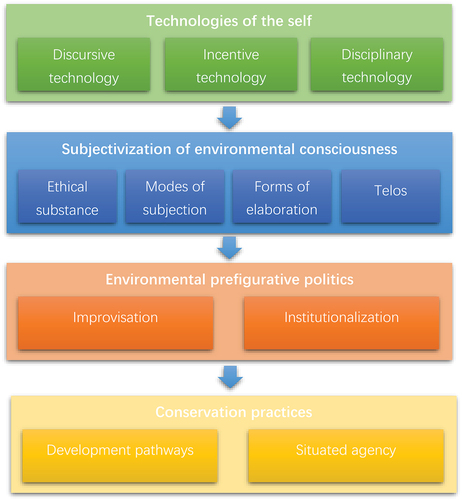

Ultimately, drawing on Jeffrey and Dyson’s (Citation2021) framework of prefigurative politics and Foucault’s idea of technologies of the self, this study develops an EPP-TS framework to explore how the mobilization of technologies of the self can be used to subjectivize individual environmental consciousness in such a way that environmental prefigurative politics shapes the concrete conservation practices (see ). This framework drives the following case study to provide an in-depth look at the complex associations between individual environmental consciousness and conservation practices.

Study area and methods

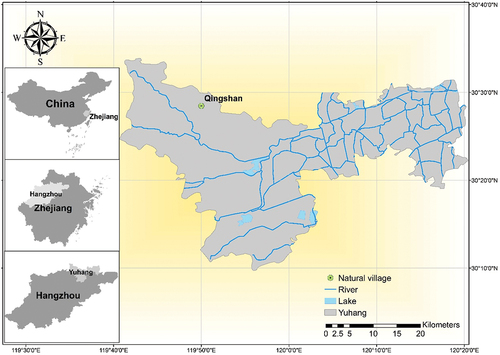

Qingshan Village, with a population of more than 2,600 people, is located in the northwestern part of Hangzhou, China, 42 kilometers from the center of the city (see ). A large number of bamboo plants are grown in the mountains around Qingshan Village, which makes the forest cover of the village close to 80%. The Longwu Reservoir, built in 1981, is located in Qingshan Village and provides drinking water for the village and the neighboring villages. When the reservoir was first built, the water quality was able to reach the highest level of drinking water. In addition, 106.67 hectares of bamboo forests are planted in the 173.33 hectares catchment area upstream of the reservoir.

The rapidly developing economy has seriously threatened the water environment of Qingshan Village. In order to promote economic growth and improve villagers’ income, many bamboo processing factories have been gradually established in Qingshan Village since the 1980s. In order to provide more bamboo to these processing factories, villagers used large amounts of chemical fertilizers and herbicides in the bamboo forests around the reservoir, which triggered widespread surface source pollution in the reservoir. Although the village committee has tried to reduce water pollution through publicity and education, the private contracting system of bamboo forests has not improved the deterioration of water quality due to the pursuit of maximizing economic returns.

In an effort to completely reverse the continuing deterioration of water quality, The Nature Conservancy (TNC), Alibaba Foundation, and Wanxiang Trust established the Longwu Water Fund (LWF) with a grant of 330,000 CNY in 2015 to protect the water source of Qingshan Village. The program reduces surface source pollution caused by chemical fertilizers and pesticides by transferring local villagers’ rights to bamboo forests, which helps improve the water quality of Longwu Reservoir. Eventually, the water quality of Longwu Reservoir rose from a level that was initially only available for industrial use to the highest drinking water level in 2018. With the gradual improvement in water quality, Qingshan Village has attracted many young urban residents to move to the area. These new residents, in turn, attempted to promote the further development of Qingshan Village by developing traditional handicrafts, environmental education, and ecotourism (Wang Citation2023). Ultimately, Qingshan Village was included in the pilot program of the “Future Village” experiment by the Zhejiang Provincial Government in 2020.

This study employs content analysis, semi-structured interviews, and participant observation to investigate how environmental prefigurative politics mobilizes technologies of the self to subjectivize individual environmental consciousness in order to shape specific conservation practices in Qingshan Village. This study first reviewed more than 20 Chinese-language academic literature and media reports on Qingshan Village conservation practices. The Chinese academic literature was obtained from China National Knowledge Network (www.cnki.net), China’s largest Chinese literature database.

I conducted fieldwork in Qingshan Village in July 2022 and April 2023. Semi-structured interviews with six government officials involved in conservation practices in Qingshan Village were conducted using convenience sampling and snowball sampling. Interviewed government officials were selected based on their familiarity and experience with involvement in nature conservation in Qingshan Village. Issues covered in the interviews included participants’ perspectives on the LWF and Future Village Experiment, as well as their specific practices. Each interview generally lasted 30 to 60 minutes and was audio-recorded.

This study adopted participant observation to understand the role of environmental prefigurative politics and technologies of the self in the conservation practices of Qingshan Village. We participated in some working meetings in Qingshan Village and interviewed some of the village’s original and newly moved villagers. Fifteen villagers were interviewed in this study using convenience sampling for an average of 10–15 minutes. Where possible, we wrote field notes for each interview and working meeting and coded these documents using qualitative thematic analysis. This study takes this survey data as background information and the previously constructed EPP-TS framework to explore how individual environmental consciousness can be subjectivized through mobilizing technologies of the self so that environmental prefigurative politics can shape concrete conservation practices.

From water source protection to futural villages: the environmental prefigurative politics in Qingshan Village

This section explores the conservation practices of Qingshan Village and the evolution from a water fund to a future village. In this process, various technologies of the self are mobilized to subjectivize individual environmental consciousness. This subjectivization facilitates the realization of environmental prefigurative politics that influences the development pathways and situated agency of nature conservation in Qingshan Village and shapes, as well as shaping specific practices.

Longwu water fund aimed at realizing water source protection

Water source protection led to the implementation of the LWF. The prefiguration of nature conservation reflects a collectively held, institutionally stable, and publicly enforceable vision of a desirable future for nature conservation (Jasanoff Citation2015). TNC, in cooperation with the local government where Qingshan Village is located, has constructed an environmental prefiguration consisting of water source protection, green industry development, and nature education. This environmental prefiguration is bluntly expressed in Qingshan Village as “clear waters and lush mountains are gold and silver,” implying that nature is the most critical asset. This metaphor derives from the Chinese state’s ecological civilization imaginary for the future. Propagated as focusing on human-nature relations, ecological civilization was created as a sustainable imaginary in the Chinese state and elevated to constitutional status in 2018 (Sheng and Cheng Citation2024). This imaginary hints at China’s attempt to realign the relationship between conservation and development, allowing for a shift from opposition to mutual realization between conservation and development (Sheng, Ding, and Han Citation2022). In 2014, prior to the LWF’s establishment, Qingshan Village was still a relatively poor village in eastern China, with an average household income of only 60,000 CNY/year and a quarter of that coming from the cultivation of moso bamboo and bamboo shoots. Bamboo cultivation has not brought prosperity to the villagers but has caused severe water pollution. TNC introduced the concept of small water source protection in Qingshan Village, which provided a vision of a better future for the village. A village official from Qingshan Village commented, “We were all aware that Qingshan Village’s strength was its favorable environment, but we didn’t have a clear idea of how to develop it. That’s when the TNC team came to Qingshan Village in 2015 and brought us the concept of small water source protection. At that time, TNC portrayed a promising model for future development, backed by talent and industry. After listening to their presentation, we were immediately impressed by the program” (Transcript QS01). Shortly thereafter, TNC, Alibaba Foundation, and Wanxiang Trust formed the LWF to support water source protection in Qingshan Village.

In order to achieve water source protection, LWF tries to mobilize discursive technology to change the villagers’ way of production and lifestyles. Discourse technology is the construction of knowledge about nature through a conscious and sustained effort to increase people’s understanding of nature conservation and discover plasticity for concrete action in non-discursive areas (Foucault Citation2023). TNC, with its expertise in nature conservation, has become an advisor to the LWF, which is responsible for promoting changes in the production and lifestyle of local villagers based on the concept of nature conservation. Every year, TNC organizes volunteers to carry out public service activities and guides farmers to weed the bamboo forests to eliminate the use of herbicides. As one of the villagers who participated in the training commented, “Before, I was not aware that the pesticides used to grow bamboo could cause such serious harm to the water quality of the reservoir. TNC organizing these activities made me realize the flaws of the original production methods” (Transcript QS13). In addition, the LWF failed to gain widespread acceptance at the beginning of its implementation due to the fact that the local community knew little about the program. For instance, one villager claimed, “At that time, the LWF staff persuaded us to transfer the right to use 13 mu (0.87 hectares) of bamboo forest, I did not believe at all that the program transferred the forest land only for the protection of the reservoir, nor did I believe that we could receive adequate compensation” (Transcript QS08). In order to construct discourse and gain villagers’ trust, the LWF brought many knowledge domains, expert institutions, and organizations into common localization. A village official commented, “Our village has held several meetings of village representatives to unify ideas. At the same time, the village also arranged for a retired village official who was familiar with the situation to work with TNC staff to do public work. This village official was the first to join the LWF program and helped convince other villagers of the LWF’s future value and their willingness to join” (Transcript QS01). This evidence suggests that the LWF’s discursive creation for nature conservation produces transformative conditions that constitute subjective regulation. The transformation of local villagers’ production and lifestyles is shaped through invisible or continuous control practices, rather than being triggered by top-down systems of power or justice (Foucault Citation2023). This discursive technology regulates individual behavior by creating a transformation network and correcting individuals who deviate from the norm.

Incentive technology is crucial for transforming individual environmental consciousness in water source protection. The LWF is essentially a specific application of Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES) in watershed management. PES is often seen as a neoliberal solution to ecological crises, advocating using external incentives to transform individuals into environmentally conscious subjects (Fletcher Citation2017). During the first trust period (2016–2021), the LWF acquired forest land use rights for over 33.33 hectares of bamboo forest from 43 farmers through forest rights transfer. Farmers participating in the LWF receive eco-compensation of no less than the income from bamboo forest operations. For instance, one farmer commented, “The LWF pays each household an average of 172 CNY/mu (2,578.71 CNY/hectare) per year in eco-compensation, which is almost 20% more than what we were previously earning from operating our own bamboo forest” (Transcript QS09). Through the bamboo forest transfer, LWF was able to centralize the management of bamboo forests, allowing it to control farmers’ use of pesticides and fertilizers. Instead of creating an actual market, the LWF’s incentive technology disseminates market value to all individuals and social actions (Fletcher and Buscher Citation2017). This dissemination of market values makes it possible to provide incentives for the transformation from individuals to subjects, so that local rational individuals, influenced by economic incentives, are willing to take nature conservation measures to maximize their utility and transform into environmentally concerned subjects.

The LWF also applies disciplinary technology to regulate the conservation behavior of local villagers. Punishment aims to evolve from retribution in the pre-modern world to the transformation of discipline violations in the modern world, thus transforming the soul to trigger behavioral change (Foucault Citation2023). Therefore, the key to disciplinary technology is discipline and control of the individual rather than physical retribution and punishment. An area of 1.9 square kilometers around Longwu Reservoir was designated as a red-line zone for ecological protection, which means it is restricted from development. The LWF and participating villagers signed covenants with clear penalties to constrain villagers’ conservation behavior. One villager commented, “We need to sign a contract with the LWF to join, which clearly states that we can no longer use pesticides and chemical fertilizers in our bamboo plantations. If we are found to have violated the rules, we will be fined or even removed from the program and unable to participate in the future” (Transcript QS11). Thus, local villagers involved in the program become aware that they are being observed and thus internalize the subject of obedience through self-regulation.

Technologies of the self contribute to the subjectivization of individual environmental consciousness in Qingshan village, making the conservation actions triggered by the LWF a practice that is completely inconsistent with the villagers’ prior experience and reflecting an important dimension of environmental prefigurative politics – improvisation (Jeffrey and Dyson Citation2021). Foucault (Citation1990, Citation1988a) argued that individuals actively form the self as a subject in the context of particular discourses, power relations, and practices. As previously demonstrated, the LWF mobilized discoursive, incentive, and disciplinary technologies to enable the villagers to first subscribe to the idea of water source protection. Afterward, driven by these technologies of the self, they submitted to prefigurative politics from the inside. They changed their behavior, thus integrating their own behavior into prefigurative politics. In 2021, more villagers transferred their bamboo forests to the LWF, increasing the 33.33 hectares of bamboo forests under its original management to 66.67 hectares. As one villager commented, “The LWF has completely changed the mindset of our villagers. Now, we all realize that our village will have a future only if we protect the environment in Qingshan Village. So now we are all willing to join the LWF program, which protects the environment of the village, and we also get income from it” (Transcript QS14). Thus, the technologies of the self mobilized by the LWF achieved the subjectivization of environmental consciousness in Qingshan village. These technologies of the self have enabled villagers to generate new reflections on their relationship with the environment (Legg Citation2016), and have made these subjects aware that present-day conservation behaviors are necessary for water source protection. These villagers internalize this environmental consciousness as truth and use it to limit their own behavior (Bergen and Verbeek Citation2021), making them willing to take conservation action in the present for the sake of water source protection.

In addition, the conservation actions triggered by the LWF were further institutionalized in order to ensure the durability of the improvisation of water source protection. In 2021, Yuhang Environment (Water) Group Co. and Huanghu Township, where Qingshan Village is located, joined LWF to co-finance a PES program for rural water source protection. A deputy general manager of the company stated, “We hope that the pilot in Qingshan Village can be further replicated to provide inspiration for water source protection in Hangzhou and even in Zhejiang, and to encourage more PES programs” (Transcript QS05). This suggests that water source protection has become more sustainable due to the institutionalization of practices involving extensive social cooperation and improvisation. Moreover, the birth of the new PES program reflects that environmental prefigurative politics are often realized in the form of new project/movement nomenclature. Ultimately, broader social collaboration and improvisation become more sustainable through institutionalization (Jeffrey and Dyson Citation2021).

Environmental prefigurative politics also reshaped the development pathways and situated agency of nature conservation in Qingshan Village, thus determining the specific conservation practices. By utilizing the experience gained in Qingshan Village, the local government developed an eco-compensation mechanism for small water sources, which in turn appeared alongside other PES elements in new water source protection projects. For example, China has since attempted to replicate the Qingshan Village experience in collaboration with TNC in the Qiandao Lake Water Fund (De Bièvre and Lorena Citation2022). The PES program for rural water source protection is thus an institutionalization of the improvisations of water source protection, which in turn provokes new improvisations in other PES programs.

Peripherality is also essential in how environmental prefigurative politics shape water conservation practices. Political-economic peripherality as a geographic concept reflects the lack of political power and economic dependence of peripheral areas on dominant areas in a network of political and economic processes (Bickerstaff, Simmons, and Pidgeon Citation2006). This strategy of peripheralization has often been adopted by the Chinese state and has led to territorial reconfiguration through the internal peripheralization of frontier and rural areas (Su and Fan Lim Citation2023). Qingshan Village is also such a peripheralized area in China. The funding and initial conception of water source protection in Qingshan Village came entirely from external NGOs. Qingshan Village has developed a culture of acceptance of water source protection, which has led to the subjectivization of individual environmental consciousness. As one village official said, “After TNC promoted and introduced the LWF policies, villagers gradually accepted and agreed with the concept of water source protection. Eventually, some villagers have joined the LWF conservation practice on their own initiative” (Transcript QS01). For Qingshan Village, which is in a peripheral area, its relationship with the core area of the country is environmentally unequal, which also leads to its lack of ability to resist external influences (Blowers and Leroy Citation1994). Ultimately, the peripheral character of Quingshan villages also makes it easy for individuals to subjectivize their environmental consciousness and ultimately accept and actively practice water source protection.

Finally, even in authoritarian contexts, transnational civil society can still actively shape the prefiguration of water source protection. Different levels of government in China often have multiple and conflicting interests in policy design and implementation, captured by fragmented authoritarianism (Lieberthal and Oksenberg Citation1988). This concept suggests that policymaking in China is often realized through incremental changes that are bargained between bureaucrats (Mertha Citation2009). Inter-bureaucratic bargaining leads them to realize that expanding civil society in the decentralization of public goods may benefit them (Teets Citation2013). In turn, international NGOs in transnational civil society may cooperate with authoritarian governments because of their dependence on the host country for material resources and political access, making the two mutually constitutive and even interdependent (H. Li, Wing‐Hung Lo, and Tang Citation2017). In the case of Qingshan Village, TNC, Alibaba Foundation, and Wanxiang Trust, as transnational civil society, co-sponsored the LWF. The emergence of the LWF led the Yuhang government to realize that the environmental prefiguration, as shaped by the former, was in line with its goal of nature conservation, which thus facilitated the government officials to get a good track record in cadre promotion tournaments. This also explains why local officials allowed the expansion of transnational civil society to emerge in an authoritarian state. Even local governments have joined the transnational civil society initiative by establishing the PES program for rural water source protection. With the help of environmental prefigurative politics, transnational civil society and authoritarian government mutually constitute each other. This formation is also known as consultative authoritarianism, i.e. the promotion of a fairly autonomous civil society alongside the development of complex and indirect instruments of state control over civil society (Teets Citation2013).

Future village experiment

Following the LWF, Qingshan Village has constructed a prefiguration of the Future Village. Forming a prefiguration involves activists working now to realize their vision of a better world (Jeffrey and Dyson Citation2021). The Future Village is an experiment constructed by the government of Zhejiang Province, where Qingshan Village is located, which includes a depiction of the future industry, landscape, culture, community, health, environment, transportation, and smart scenarios of the village (GOPGZP Citation2022). Qingshan Village has become the first pilot site for this experiment. Indeed, before implementing the LWF, Qingshan Village was an obscure hamlet. The village used to have a registered population of about 3,000, but no more than 1,500 actual residents. The young people of the village, like most people, migrated to the cities as migrant workers. With the LWF’s implementation, many young people have been attracted to Qingshan Village and have settled there temporarily. More than 80 young people between the ages of 25 and 45 have migrated from the city by 2022. While volunteering at TNC, they also began considering further nature conservation in Qingshan Village to revitalize the village. Seeing the growing prosperity of Qingshan Village driven by young people, the Zhejiang Provincial Government officially launched the Future Village, which envisions a nature-friendly and digitized rural lifestyle (Wang Citation2023). Qingshan Village was also officially chosen as a pilot area for the Future Village experiment in 2020.

Discursive technology is first mobilized to subjectivize individual environmental consciousness in the Future Village experiments. With the support of TNC, young people who moved to Qingshan Village converted the abandoned elementary school into the Qingshan Nature School in 2017 to spread conservation knowledge and provide nature education. One of the young people commented, “The main purpose of the Qingshan Nature School is to popularize conservation knowledge in the village, such as advocating villagers to protect water sources, reduce the use of disposable items and separate garbage, so as to guide original villagers to practice environmentally friendly production and lifestyles” (Transcript QS03). In addition, more than 20 designers worldwide have transformed the abandoned auditorium in Qingshan village into an art library called “Rong Design” to guide villagers to participate in the discovery and research of traditional Chinese handicrafts, and ultimately to realize a more sustainable way of life. A village official commented, “When the library first arrived, the villagers didn’t understand it and didn’t think it would be useful. After many exchanges with the library team, we were convinced and determined to introduce the program. The villagers did not accept the program at the beginning, so our village committee went door-to-door to convince them one by one. By the end of 2022, more than 200 villagers in Qingshan Villiage had joined the library program” (Transcript QS02). This evidence suggests that the nature education and sustainable lifestyles guided by the Qingshan Nature School and the Rong Design Library have been implicitly accepted by the villagers and are being used to regulate their behavior.

In addition, the discursive technology in the Future Village experiment is not only for the original villagers but also for the new villagers to achieve self-transformation. In order to establish a greater connection with nature, the new villagers are encouraged to adopt an environmentally friendly lifestyle. They try to make the best use of existing products and create designs from them, as well as organize secondhand markets and exchange things to reduce waste as a symbolic means of expressing their own narratives. As one new villager stated, “After moving to Qingshan Villiage, I fell in love with the feeling of connecting with nature. It gives me a sense of inner peace and reduces my anxiety about life” (Transcript QS04). These new villagers also interacted with the original villagers during the implementation of the Qingshan Nature School and the Rong Design Library, thus rebuilding relationships between people. By interacting with others, the new villagers also found the ethical substance of the self. As one of the new villagers said, “There are a lot of interesting people here, and we do meaningful things together. Everyone can find their own values in their own way” (Transcript QS06). Thus, the discourse of nature conservation can provide criteria for identifying problems and developing solutions, thus contributing to the subjectivization of individual environmental consciousness (Elshimi Citation2015).

In the Future Village experiment of Qingshan Village, the transformation of the villagers’ production and lifestyle also relies on incentive technology. Neoliberalism, as applied to nature conservation, creates external incentives to make individuals, as rational actors, exhibit appropriate behavior (Fletcher Citation2010). The LWF attempted to rely on selling pesticide-free ecological bamboo shoots to generate income and reward villagers for their conservation behavior. However, as many farmers stated in interviews, the high costs and low returns of operating ecological bamboo shoots have resulted in a lack of competitive advantage for the industry. Fortunately, Qingshan Village is close to the city, and local businesses (e.g. Alibaba) have a need for nature education. Consequently, the Future Village experiment in Qingshan Village has shifted the focus of industry development to ecotourism based on nature education experiences. Ecotourism is widely used as an essential strategy for nature conservation and developing communities due to its ability to generate income that can be used to manage protected areas sustainably, provide local employment opportunities, and instill a sense of community ownership (Das and Chatterjee Citation2015). This form of tourism has become a major motivation for tourists to visit Qingshan Villages due to its high relevance in promoting conservation practices. For instance, the Qingshan Nature School has developed dozens of specialty ecotourism products. It attracts tourists and students to Qingshan Village to participate in eco-experiences and nature education through partnerships with more than 50 schools and 100 businesses.

The environmental consciousness of local villagers is also gradually changing in the development of ecotourism. Qingshan Village has set up a program called “Nature’s Good Neighbors” to increase the income of local villagers by developing their unused houses into bed and breakfasts (B&Bs). A village official declared, “The village and the villagers who join the ‘Nature’s Good Neighbors’ have signed an agreement not to provide disposable goods and consciously practice ecological and environmental protection. The village will prioritize recommending B&Bs that have good results in practicing ecological and environmental protection on ‘Nature’s Good Neighbors’. More than 70 households in the village have joined the program, with an average household income of more than 30,000 CNY, driving more than 200 villagers into direct employment” (Transcript QS02). Thus, incentive technology enables individuals to internalize the fundamentals and logic of various nature conservation(Sarmiento, Landstrom, and Whatmore Citation2019), which works by seeking to shape the multiple rationalities of individuals (Soneryd and Uggla Citation2015).

Qingshan Village has also mobilized disciplinary technology to achieve the future village. Disciplinary technology is premised on the idea that behavioral change is achieved through cognitive rather than behavioral change (Elshimi Citation2015). For instance, a villager participating in “Nature’s Good Neighbors” commented, “After joining the program, I cannot use disposable paper cups and plastic bags while operating my B&Bs. Moreover, I must also give 10% of my profits to the water fund every year to protect the water source of Longwu Reservoir ”(Transcript QS11). In addition, Qingshan Village has also adopted the Future Village Council to develop village rules and regulations as a way to change villagers’ perceptions and behaviors. New villagers moving in from the city and the original villagers have different living and educational backgrounds; thus, conflicts are often compiled inevitably. For instance, introducing water tariffs in 2020 in Qingshan Village made the originally free water become paid for, which led to the original villagers being unable to accept it. An original villager recalled, “We used to use the water from Longwu Reservoir for free, so why should we be made to pay for water now?” (Transcript QS13). The new villagers, on the other hand, generally thought that paying water tariffs was a normal thing to do. Eventually, the Future Village Council, which encompassed both original and new villagers, was created and used to reconcile conflicting interests and set guidelines for behavior. In the end, the Future Village Council worked out a compromise whereby the water price was charged at 80% of the standard price, and the original villagers were each given two tons of water per month free of charge. This proposal ultimately changed the perceptions of the original villagers and, in turn, led them to self-adjust their water use behavior. Such disciplinary technology can force subjects to self-regulate by requiring them to internalize specific norms and values (Fletcher Citation2010).

Through the mobilization of various technologies of the self, individuals in Qingshan Village have accomplished the subjectivization of their environmental consciousness, making environmental prefigurative politics possible through the improvisation of available states of thought and emotion. Improvisation in environmental prefigurative politics often involves a bold attempt to move forward and establish a stark contrast between the environmental prefiguration and the current environment (Jeffrey and Dyson Citation2021). As previously analyzed, through nature education, ecotourism, and the Future Village Council, the Future Village experiment is transformed into ecological knowledge that coordinates and facilitates the subjectivization of individual environmental consciousness, thus realizing the management of the mind (Brady Citation2011). With the help of technologies of the self, villagers reflect on their living with the environment based on the ecological knowledge and internalize it as truth to regulate their behavior (Foucault Citation2017). In this sense, the subject becomes environmentally conscious by absorbing ecological knowledge, which makes him/her willing to take conservation actions in the present to realize the future village. For example, an original villager commented, “These measures in the Future Village experiment have changed our perceptions and made us realize that protecting the environment is valuable. We can also increase our income through conservation. Now our attitude towards the Future Village experiment has changed from refusal or wait-and-see at the beginning to active participation” (Transcript QS17).

In addition, the Future Village experiment in Qingshan Village further institutionalizes environmental prefigurative politics by summarizing the experimental experience. Based on the Future Village experiment in Qingshan Village, the Zhejiang Provincial Government has issued a province-wide guideline for constructing future villages in an attempt to build an ideal vision of the future: the leading industries are prosperous and developed, the natural landscape is beautiful and livable, and the thematic culture is booming and thriving (GOPGZP Citation2022). The bottom-up institutionalization from individual experimentation to full-scale rollout has made the change in environmental prefigurative politics more durable. An official from Zhejiang Province, where Qingshan Village is located, said, “At present, 567 future villages have been built in Zhejiang. By the end of 2025, the number of future villages in the province will reach 1,000” (Transcript QS07). The expansion of future villages in Zhejiang reflects the institutionalization of environmental prefigurative politics to integrate localized prefigurative organizations into broader alternative futures (Jeffrey and Dyson Citation2021).

In the subjectivization of individual environmental consciousness, environmental prefigurative politics also changed the development path and situated agency of nature conservation in Qingshan Village, ultimately shaping the conservation practices of the future village. The experience in the Future Village experiment in Qingshan Village was institutionalized as a provincial future village construction project and has triggered new improvisations in the construction of future villages in other regions. For example, Anding Village in Hangzhou recruited a professional operation team to brand the future village (Pei Citation2022). These practices further suggest that the prefigurative politics of future villages have changed the institutional, social, and cultural norms of Qingshan Village, thereby reshaping the local development path. In turn, the altered power relations and the rise of new institutional arrangements triggered by prefigurative politics also reflect that local actors will respond to changing prefigurative politics by altering the situated agency (Kolinjivadi et al. Citation2019).

The environmental prefigurative politics of the Future Village are also closely related to peripherality in promoting the subjectivization of individual environmental consciousness. The territorial configuration of internal peripherality tends to result in peripheral areas often being reduced to enclaves of dominant areas (Hong Citation2020). The development of ecotourism in Qingshan Village mainly aims to attract residents from nearby big cities. In addition, villagers joined the “Nature’s Good Neighbors” program to earn income by serving outside tourists. One village official declared that “villagers joined the ‘Nature’s Good Neighbors’ program mainly to attract tourists from downtown Hangzhou, which greatly improved their income” (Transcript QS02). These practices all point to the political and economic inequality between the peripheral village and the dominant city, which leads to the former’s economic dependence on the latter and its lack of ability to resist the latter’s influence. The resulting inequality makes villagers willing to accept and participate in the concrete practices of the Future Village experiment, which facilitates the realization of environmental prefigurative politics for the subjectivization of individual environmental consciousness.

Finally, the development of domestic civil society in the context of authoritarianism is also included in the prefiguration of the Future Village. Under China’s fragmented authoritarianism, the expansion of civil society contributes to the provision of public goods, which aligns with the interests of local officials (Teets Citation2013). Unlike the transnational civil society in LWF, the external new villagers, who embody domestic civil society, constantly try to promote environmentally sound production and lifestyles. These new villagers negotiate with local officials and original villagers through the Future Village Councils, thus jointly shaping and constructing the prefiguration of the Future Village. However, this consultation is not democratization, but a more complex form of consultative authoritarianism. In this context, the development of domestic civil society has also contributed to the enrichment of the state’s means of controlling civil society (Teets Citation2013). The government realized the positive role of domestic civil society in shaping environmental prefigurative politics, thus promoting larger-scale future village construction in Zhejiang (GOPGZP Citation2022). Through the development of domestic civil society, the government can utilize environmental prefigurative politics to manage people’s minds on a larger scale (Brady Citation2011).

Discussion

A range of technologies of the self, including discursive, incentive, and disciplinary technologies, are mobilized to subjectivize individual environmental consciousness. Foucault (Citation1982) argued that the subject contains two layers of meaning: submission to others through control and dependence, as well as being linked to one’s own identity by self-recognition. Individuals are transformed into subjects by external events and actions taken by individuals. These external events and personal actions constitute technologies of the self, i.e. specific technologies that humans use to understand themselves (Foucault Citation1988b). Since there is always a gap between the efforts of subjects to reinvent themselves and the technologies of power that institutional design seeks to consolidate, the resulting processes of context-specific subjectivization are as contingent as they are political (Agrawal Citation2005). As demonstrated in this study, the LWF adopted technologies of the self, including the construction of a discourse of nature conservation, eco-compensation based on the transfer of forest rights, and contracts with penalties, to facilitate changes in local villagers’ production and lifestyle based on the improvisation of water source protection. Since then, the Future Village experiment has further mobilized technologies of the self, including nature education, ecotourism, and the Future Village Council, to transform the improvisation of the future village into ecological knowledge, thereby coordinating and changing the subjective behaviors of individuals, including both original and new villagers. These technologies of the self can be summarized into three types: discursive technology, by shaping future visions of nature conservation into concrete discourses; incentive technology, by creating external incentives to guide individuals to exhibit appropriate behaviors; and disciplinary technology, by constraining individual behaviors through the rationality of institutions, interventions, and plans. In the change of improvisation from water source protection to the future village in Qingshan Village, various technologies of the self, including discoursive, incentive, and disciplinary technologies, are mobilized to make these environmental prefigurations recognized by the individuals, and then to take the conservation behavior of obeying and even pursuing these environmental prefigurations. Through the mobilization of multiple technologies of the self, the villagers in Qingshan Village became aware of and identified with these environmental prefigurations and internalized them as truths, thus subjectivizing their environmental consciousness. Villagers see this environmental consciousness as truth and use it to regulate their own conservation behavior. In the subjectivization of individual environmental consciousness, the individual moves from passive obedience to active subjectivization, thereby transforming the self and choosing the “right” way of life (Hanna Citation2013).

The subjectivization of individual environmental consciousness prompts and institutionalizes the improvisation of environmental prefigurations, embodying the political imaginaries and power structures that environmental prefigurative politics aspire to realize in society. Agrawal (Citation2005) argued that attention should be focused on particular social practices related to subjectivization, which helps to understand how practices of nature conservation influence ways of thinking about the world and create opportunities for the production of new subjects. The subjectivization of the individual environmental consciousness, triggered by technologies of the self, can also further enable and institutionalize individual improvisation, which in turn triggers a tension between improvisation and institutionalization. Prefigurative politics relies on the realization of an intensive commitment to improvising existing ideas, materials, spaces, bodies, and emotional states (Jeffrey and Dyson Citation2021). In the case of Qingshan Village, individuals were driven by these technologies of the self to become internally subservient to environmental prefigurations and immediately made changes in the way they behaved. The technologies of the self mobilized by the LWF made more villagers willing to join in, thus expanding the area of the transfer of forest rights. The Future Village experiment not only actively encourages the original villagers to join the ecotourism program voluntarily, but also continuously attracts new villagers to move in as well as tourists to visit through ecological experience and nature education. Moreover, institutionalization further makes the conservation practice of environmental prefigurative politics more sustainable. The improvisation of water source protection was institutionalized into the more general PES program, and the Future Village experiment in Qingshan Village was institutionalized and replicated. In the case of Qingshan Village, the improvisation of water source protection was institutionalized into a more general PES protection program. As previous evidence suggests, water source protection actions are incorporated into the PES program for rural water source protection constructed by two institutional agents: state actors and NGOs. In turn, the improvisation of the Future Village in Qingshan Village was institutionalized by state actors into the more general province-wide Future Village Construction Project. As previous analyses have shown, the institutionalization of improvisation, in turn, provokes new improvisations. The institutionalized PES program and Future Village Construction Project that resulted from the Qingshan Village experience was, in turn, applied to other regions, where it provoked new improvisations. Thus, improvisation and institutionalization are not linear (Jeffrey and Dyson Citation2021), but rather are intertwined and mutually reinforcing. Ultimately, through implementing the LWF and the Future Village experiment, environmental prefigurative politics was gradually realized in Qingshan Village. In individual subjectivization, power is also reconfigured and shaped into new power structures. As demonstrated in the previous analysis, environmental prefigurative politics has reconfigured power among the original villagers, the new villagers, the local government, and the social organizations. The power reconfiguration has contributed to the evolution of environmental prefigurative politics from the LWF, which was designed to realize water source protection, to the Future Village experiment.

Furthermore, environmental prefigurative politics also influence the development pathways and situated agency of nature conservation, thereby shaping specific conservation practices. Prefigurative politics can influence specific practices through the ways in which people seek to formulate visions of the future (Jeffrey and Dyson Citation2021). As this study demonstrates, environmental prefigurative politics first affects the development pathways of nature conservation in Qingshan Village. The LWF changed the original production mode of Qingshan Village, which was dominated by the bamboo cultivation industry, so that villagers could benefit from their conservation behaviors. The Future Village experiment transformed the abandoned elementary school and auditorium in Qingshan Village into a vehicle for ecological experience and nature education. Environmental prefigurative politics in Qingshan Village transforms water source protection and ecotourism into scarce commodities that are attempted to circulate freely among stakeholders through market or market-like mechanisms (Sheng and Han Citation2022b). In addition, environmental prefigurative politics has also changed the situated agency of Qingshan Village. The LWF, initially dominated by non-governmental organizations represented by TNC, has gradually incorporated state-owned enterprises and local governments into the conservation practices of Qingshan Village, resulting in a broader PES program for water source protection. Similarly, the subjectivization of individual environmental consciousness in the Future Village experiment makes nature conservation an ecotourism resource and reconfigures power relations by constructing the Future Village Council. The development pathways of nature conservation triggered by environmental prefigurative politics and the dynamic interplay between the situated agencies shape the pluralistic co-production of conservation practices (Shapiro-Garza et al. Citation2020).

Attention to the spatial tensions of peripherality contributes to understanding the processes by which environmental prefigurative politics shape nature conservation practices. Peripherality as a geographic concept is constituted in two interrelated ways: geographic remoteness and political-economic margins (Bickerstaff, Simmons, and Pidgeon Citation2006). The former implies remote places far from centers or metropolises where capital and infrastructure are concentrated, while the latter means that the economic lifeblood and political power of the periphery are determined by the dominant region (Blowers and Leroy Citation1994). In the case of this study, Qingshan village is clearly a peripheral area in China. From its initial bamboo origin, to its clean water source, and finally to its “natural” experience, the conservation practices of Qingshan Village were created for consumers from Hangzhou. Qingshan Village’s “Nature’s Good Neighbors” program provides B&Bs for consumers from the metropolis, thereby providing income for local villagers. However, the economic lifeblood of this program is entirely determined by external consumers, and local villagers lack the ability to resist the influence of consumers from the big city. Thus, the prefiguration of the Future Village is not set up by Qingshan Village itself. Still, the peripheral Qingshan Village is merely a test site in the environmental prefigurative politics of the Future Village. Another example of peripherality comes from the water tariff reform in QIngshan Village. The prefiguration of water source protection was also not proposed by the original villagers of Qingshan Village, but was constructed by NGOs. However, the original villagers in Qingshan Village were unable to resist this external influence and were required to pay for water conservation. PES is designed to incentivize individuals and/or collectives to align their individual and/or collective interests with those of society in managing natural resources (Muradian et al. Citation2013). Consequently, the original villagers in Qingshan Village paid for water and, at the same time, received eco-compensation or ecotourism benefits from water source protection. These pieces of evidence suggest that political tensions of peripherality in environmental prefigurative politics shape specific conservation practices. Attention to the spatial tensions of peripherality, therefore, enhances understanding of the environmental prefigurative politics, which in turn mediates the practical experience of nature conservation.

The environmental prefigurative politics under authoritarian environmentalism also strengthens authoritarian power in subjectivizing individual environmental consciousness. Ostrom (Citation2015) argued that participatory forms of resource management would contribute to realizing socially just environmentality. However, this form of participatory resource management does not exist in the case of Qingshan Village. Although the water source protection in Qingshan Village was initially initiated by NGOs represented by TNC, state and local influence on the project was omnipresent. The political imaginary of water source protection and future villages in Qingshan Village is seen as part of China’s national imaginary of ecological civilization, and as a concrete practice and typical example of this imaginary (Zhao Citation2023). In addition, as previous analyses have shown, TNC’s LWF and the launch of the “Nature’s Good Neighbors” program are also dependent on local government support and intervention. In the political imaginary of water source protection and future villages, the participation and supervision of local residents are still extremely limited. In the subjectivization of individual environmental consciousness, water source protection has become a new space of politicization in which national and local governments use ecological knowledge to consolidate power over rural lands and individuals through cooperation with TNCs (Rodenbiker Citation2023). These evidences also reflect the fact that China may only be utilizing the appearance of greenness to consolidate its power over territories and individuals, and thus authoritarianism remains the main goal, while environmentalism is only a means to that end (Y. Li and Shapiro Citation2020). In this authoritarian environmental management, coercive measures are seen as a socially just component of China’s environmental management, echoing the well-established view in political ecology that ecologies are power-laden rather than politically inert (Robbins Citation2020).

Finally, it is essential to note that the environmental subjectivization of Chinese individuals is becoming more cosmopolitan, reflecting the profound social and economic transformations that rural China is undergoing. Environmental subjectivization is an ongoing process that produces new forms of agency and new landscapes (Yeh and Coggins Citation2014). As previous analyses have demonstrated, the subjectivization of young people’s environmental consciousness plays a dominant role in environmental prefigurative politics compared to most older rural subjects. Young people are coming to see the countryside as a new production space and to regard rural landscapes as beautiful and healthy environments (Leyshon Citation2008). In addition, the more fusion-designed libraries transformed by young designers worldwide reflect young people’s more cosmopolitan environmental subjectivization than older villagers. And the old villagers, who were originally landholders, became the recipients rather than the prominent participants in environmental prefigurative politics (Wang Citation2023). All these phenomena strongly suggest that rural China is undergoing a profound social and economic transformation. However, young people’s bottom-up explorations of the future village are being exploited by the national and local governments, and instead become top-down goals for future rural development. Individuals who aspire to social change end up having to shape their own personal behavior according to the ideals they envision (Portwood-Stacer Citation2013).

Conclusion