Abstract

Objective

This research was conducted to explore the nature of multisectoral action for road safety in Brazil. In an effort to improve the implementation of complex interventions, we sought to characterize the relationships and exchange patterns within a network tied to the Bloomberg Initiative for Global Road Safety (BIGRS) in Fortaleza and São Paulo, Brazil.

Methods

We conducted an organizational social network analysis based on in-person surveys and key informant interviews with 57 individuals across the two cities from August to October 2019. Survey data included network dimensions such as the frequency of interaction, perceived value of interaction, resource sharing, coordination, data/research sharing, practical guidance, and access to decision makers. We coded and analyzed interview transcripts according to network properties of structure, governance, development, and outcomes, as well as in situ codes that emerged from the data.

Results

We found differences in all network properties between road safety networks in Fortaleza and São Paulo. Fortaleza was characterized by a centralized, dense, and relatively new network, whereas São Paulo was larger, diffuse, diverse, and established. Government agencies were central in both networks, but an international nongovernmental organization (NGO) was highly central in Fortaleza and a local NGO was highly central in São Paulo. Few actors on the periphery of both networks were connected to one another or decision makers, which revealed sectors to engage for enhancing network connectivity. Finally, politics were understood to be key in facilitating network activity, data (especially their integration and transparency) were considered to be influential for decision making, and strategic planning was acknowledged as a central concern for network expansion and fluidity.

Conclusions

Multisectoral action for road safety can be reinforced by carefully disentangling the social dynamics of implementation. Organizational social network analysis, supplemented with interview data, can provide a deeper explanation for how members behave and understand their work. In this way, research can help build a collective identity and impetus to action on road safety, contributing to a healthier and more equitable world.

Keywords:

Introduction

Governments around the world struggle to implement evidence-based interventions to address road safety (Hyder et al. Citation2012; Bachani et al. Citation2017). This is particularly worrying because road traffic injuries are the leading cause of death for children and adults aged 5 to 29, and 90% of these occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs; World Health Organization [WHO] Citation2018). The United Nations Decade(s) of Action on Road Safety has helped raise the profile of road safety as a public health and development concern (United Nations Citation2020). Networks, as sites of organizational learning, advocacy, and action, are central to this movement. For this reason, we call these networks “multisectoral action coalitions” (MACs) for road safety.

The Bloomberg Initiative for Global Road Safety (BIGRS) was a 5-year (2015–2019) project implemented by a consortium of partners with an overall goal to reduce the burden of road traffic injuries and fatalities in selected LMICs. Two of the 10 LMIC metropolitan areas in the BIGRS consortium are in Brazil. Fortaleza and São Paulo have both been successful, to varying extents, at reducing the prevalence of risk factors for road traffic injuries over the life of the project (Andreuccetti et al. Citation2019; Torres et al. Citation2020) and provide an opportunity to formally study the structure of MACs within each city and the role they played in addressing road safety.

Fortaleza and São Paulo differ in several important ways. Fortaleza, a northeastern city with a population of 2.7 million, is an important destination for cultural and environmental tourism (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística [IBGE] Citation2021a). São Paulo, a southeastern megacity with a population of 12.1 million, is a major center of commerce and industry (IBGE Citation2021b). As the largest metropolitan area in the Western and Southern Hemispheres, São Paulo’s scale is important in understanding differences with Fortaleza. In terms of area, São Paulo is approximately 5 times larger than Fortaleza (1,521,110 km2 versus 312, 00 km2). Their population densities are similar: 7,398/km2 and 7,786/km2 for São Paulo and Fortaleza, respectively. São Paulo is both sociodemographically more diverse and wealthier (gross domestic product per capita of US$11,700) than northeastern cities, such as Fortaleza (gross domestic product per capita of US$5,000; Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística [IBGE] Citation2021a, Citation2021b). Nevertheless, socioeconomic disparities are present in both cities: the Gini indexes of per capita incomes are 0.6453 and 0.6267 for São Paulo and Fortaleza, respectively (Ministry of Health [MOH] Citation2021). The rapid pace of urbanization has resulted in dense and often congested infrastructure in São Paulo, and increasingly in Fortaleza, with worrying implications for road safety.

In Brazil, approximately 41,000 people die from road traffic injuries annually (WHO Citation2018). The mortality rate of Brazil is 19.7 per 100,000 population, one of the highest in Latin America (WHO Citation2018). Fortaleza, with 1.1 million registered vehicles, has a mortality rate of 8.6 per 100,000 population (Sistema de Informação de Acidentes de Trânsito de Fortaleza [SIAT-FOR] Citation2019). São Paulo has experienced a 97% increase in the motorization rate to 61.6 vehicles per 100 people (from 2002 to 2015) and has a mortality rate of 7 per 100,000 (Vias seguras Citation2017; Sistema de Informações Gerenciais de Acidentes de Trânsito do Estado de São Paulo [INFOSIGA SP] Citation2020). Despite the relatively high burden of road traffic injuries in Brazil, these 2 cities have demonstrated improvement in drink driving, seat belt use, helmet use, and speeding (Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Citation2020a, Citation2020b).

Though MACs are not new, surprisingly little has been published about their ability to improve project implementation. It is known that road safety networks are mostly constituted by government organizations that have a central role in facilitating contacts and direct resource flow (Naumann et al. Citation2019). In addition, social network analysis (SNA) is increasingly used to understand interactions among actors in public health programs (Valente Citation2010). Recently, researchers have focused on intersectoral collaboration at the organizational level in SNAs in LMICs (Hoe et al. Citation2019). In the United States, SNA has been used to characterize and compare road safety within cities of the “Vision Zero” network (LaJeunesse et al. Citation2018; Naumann et al. Citation2019).

The overall goal of this study is to better understand multisectoral action for road safety in Brazil. Similarly, this work contributes to recent moves to leverage the power of SNA to strengthen program implementation (Valente et al. Citation2015). This research aims to address the following three basic research questions: (1) How do multisectoral action coalitions become organized? (2) How multisectoral action coalitions are perceived to emerge? (3) How does information diffuse through multisectoral action coalitions? In answering these questions, we use quantitative and qualitative data to provide a social explanation of organizational interaction in road safety.

Methods

This mixed methods study was conducted as part of multicountry case study to understand more about the structure of partnerships in BIGRS in 2019–2020. Data collection involved conducting sociometric surveys and key informant interviews with members of the MACs in Fortaleza and São Paulo in August and October of 2019, respectively. This study was determined to be non–human subjects research and, as such, was exempted from review by the Institutional Review Board at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Data collection

This study was piloted in Baltimore, Maryland, and conducted in Fortaleza and São Paulo, Brazil. A sociometric survey was developed based on established network properties (Provan et al. Citation2007; Valente Citation2010) and in collaboration with road safety experts. Similarly, a draft interview guide and codebook was developed to better interpret situated social phenomena (Marshall and Rossman Citation2011). These were loosely organized by a framework of network properties described by Provan et al. (Citation2007). Three pilot interviews were conducted with BIGRS team members (not working in the Brazilian cities). Surveys and interview guides were revised, primarily for clarity and simplicity, based on the feedback. Finally, the codebook was reorganized and amplified after 2 investigators double-coded a set of 4 key informant interviews.

A fixed-list sampling scheme was used to identify key constituents of MACs in each city (Doreian and Woodard Citation1992; Naumann et al. Citation2019). This list was constructed by triangulating responses from a BIGRS study team member managing observational data collection in each city as well the lead implementing partner, a U.S.-based nonprofit, for the BIGRS project in each city. Each identified leading road safety figures in their city and provided contact information. Potential study participants were affiliated with government, international and national nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), academia, and other civil society organizations.

Each contact was approached to participate up to 3 times, first by e-mail and then by telephone, in Portuguese and English. Each was provided with a background document in Portuguese and asked to provide oral consent to participate. For consenting participants, an in-person interview time and location were scheduled at their convenience, often their place of work. Though there were no refusals, some participants did not respond and were not pursued further. The response rate was 82% for Fortaleza and 87% for Sao Paulo.

Interviews were conducted in 2 parts, in English or in Portuguese. First, a tablet-based survey was completed that asked participants to list up to 10 of the most important members of the MAC in their city and their organizational affiliation. The survey included other network dimensions such as their frequency of interaction (0–3), perceived value of interaction (0–3), and whether the contact shares resources (y/n), coordinates the network (y/n), shares data/research findings (y/n), provides practical guidance (y/n), or provides access to decision makers (y/n). Where multiple participants from one organization were interviewed, their survey responses were averaged, similar to other organizational SNA in road safety (Naumann et al. Citation2019). This process took between 20 and 30 min to complete. No participants declined to proceed to the next phase.

Second, each study participant was asked open-ended questions related to the structure of the network and how information diffuses through various channels. Also, study participants were asked to explain how they understood the network to have changed over time. Interviews lasted approximately 30 min to 1 h and included field notes compiled by the interviewer. Audio recordings were transcribed and translated verbatim using an external service and analyzed in CitationNVivo 12.

Data analysis

For the network analysis, we used sociograms and social network measures to analyze the structure of relationships in both cities. We calculated centrality measures, weighting the connections by frequency of interaction. Centrality is a measure of a node’s overall influence in the network and is measured by (1) degree (a node’s number of connections), (2) closeness (a node’s distance to other nodes), and (3) betweenness (a node’s frequency of location in the connection between 2 other nodes). Finally, we calculated an eigenvector measure (a node’s connection to other well-connected nodes) and reach (portion of a network within 2 steps of an element) to understand key organizations for information flow (Valente Citation2010; Kumu Citation2020). Collectively, these measures locate the primary leaders within a network and the extent to which they engage and broker assets with others. All network visualizations were constructed using Kumu (Citation2020), and statistical analyses were carried out using CitationSTATA version 15.

To analyze data from the semistructured key informant interviews, we developed a codebook based on 4 properties of networks, including their structure, governance, development, and outcomes (Provan et al. Citation2007). In addition, we incorporated several in situ codes that emerged from the data. One researcher coded all interview transcripts with the support of another, using NVivo 12. Rigor was pursued through peer debriefing (with BIGRS team members), triangulation (between data sources), and reflexivity (in field notes).

Results

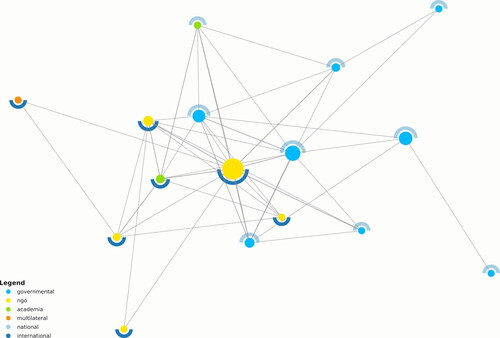

The size and distribution of organizational coalition members varied between cities (see ). In Fortaleza, 28 individuals were interviewed, which yielded a network of 84 individuals and 155 unique connections, or 16 organizations with 67 unique connections. In São Paulo, we interviewed 29 individuals, which accounted for 112 individuals with 191 unique connections, representing 32 organizations with 82 unique connections. Density scores were compared between cities, and Fortaleza had a greater degree of concentration (0.56) than Sao Paulo (0.17). describes the characteristics of the road safety networks in more detail.

Table 1. Characteristics of road safety networks.

Quantitative findings

Social network analysis was used to illustrate organizational relationships within the MACs in each city. As shown in , in Fortaleza, national government agencies were the most prevalent MAC members (8 nodes) and correspond to 50% of the network. However, government agencies are less connected (degree: 7.63) in comparison to NGOs and academia, which have networks of smaller size (5 and 2 nodes, respectively) but higher degree (9.6 and 11.5, respectively). In this closely tied network, given its high reach efficiency, each member’s connection granted them more reach and visibility within the network.

Table 2. Network metrics by type of organization.Table Footnotea

In São Paulo, NGOs were the most prevalent MAC members (22 nodes) but governmental agencies had the highest number of connections (degree: 9), can spread information to the rest of the network most easily (closeness: 0.56), and are the leaders of the network (eigenvector: 0.06). However, NGOs and academia are less connected but gain more exposure through each direct relationship (reach efficiency: 0.6).

In both cities, NGOs had the highest betweenness; hence, they enabled the flow of information across the network. In addition, multilateral agencies were not fundamental for information flow (betweenness: 0) but had the same ability as other members to spread information and being visible across the network (closeness: 0.53 and 0.44). Overall, reach was higher in Fortaleza, meaning that actors on average were able to more efficiently connect with one another than in São Paulo. Academia was not a central organization in either network but was connected to the most central organizations in both networks.

Visualizations can demonstrate how instrumental action is distributed within the network. The largest nodes are the organizations with the highest betweenness centrality, meaning that they facilitate access to decision makers. As shown in , for Fortaleza, the primary member of the MAC was an international NGO, responsible for coordinating the MAC, and in that capacity distributed financial resources and technical knowledge. As shown in Appendix (see online supplement) for São Paulo, the primary member of the MAC was a national NGO, positioned close to other central actors from the government and acting as a key bridge within the network. A network visualization for Fortaleza is shown as an example (); a visualization for São Paulo can be found in the Appendix (see online supplement) for comparison.

Qualitative findings

Our qualitative data generated insights about the nature of multisectoral action for road safety in Fortaleza and São Paulo, as described in Appendix (see online supplement). In addition, a number of differences as well as shared characteristics were identified across the 2 cities.

The data suggest that important differences exist between the MACs of both cities. Though the MAC in Fortaleza is relatively smaller and more concentrated, it is also relatively newer compared to São Paulo. In São Paulo, the more diffuse and expansive network has allowed civil society organizations to proliferate, albeit at a relative arm’s length to the core of multisectoral action. Another related phenomenon is the relative instability of road safety/transport politics in São Paulo, where public officials seek to harness its symbolic power for electoral gain. In contrast, Fortaleza has benefited from a stable, consistent, and supportive presence in high-level decision-making positions. The São Paulo MAC continues to work to integrate and democratize data, whereas actors in Fortaleza emphasize the need to develop more robust data sharing platforms. Though both networks are expanding, a larger share of civil society engagement around road safety has been catalyzed by a cycling organization in São Paulo. A final important difference is that the Fortaleza MAC understands road safety to be inextricably tied to enhancing its tourist-friendly image, whereas economic considerations in São Paulo have, at times, implicated road safety as a barrier to easing congestion.

The qualitative data point to a number of shared features of MACs in both Fortaleza and São Paulo. In both cities, the actual act of planning was seen as integral to MAC expansion and maintenance. Planning enabled actors to work toward a common goal and develop clear lines of authority, which in turn helped them to better understand their own work. Another shared theme was that both cities value data to inform decision making, as evidenced by their relative (compared to other major Brazilian cities) development of data systems such as a crash data system, centralized traffic control center, and advanced enforcement systems. Nevertheless, both struggle to deal with rapidly changing societies. The proliferation of ride-sharing services, motorcycles, shared bicycles/scooters, and new surveillance technology was seen as an opportunity for developing more sophisticated “big data”–driven approaches to data collection and analysis. Moreover, in both cities, MACs expressed a desire to move beyond aggregate risk factor data and into predictive analytics (based on geography, sociodemographic characteristics, and behavior). Both cities noted that broader cultural changes around road safety have taken place as the MACs have matured but that their cities continue to disproportionately focus on automobiles, overlooking other equity-oriented considerations such as the safety of pedestrians and cyclists. The sustainability prospects of both MACs were seen to be enhanced by the convergence of environmental and health concerns in the emerging sustainable mobility paradigm in both cities.

Discussion

This research demonstrates the utility of organizational SNA, supplemented with qualitative data, to develop a richer understanding of MACs for road safety. Moreover, by adopting a comparative approach, this research generates useful insight to inform road safety programming in both Fortaleza and São Paulo, Brazil. This is important because to date relatively little comparative organizational SNA has been conducted on road safety and, to the best of our knowledge, ours is the first in an LMIC.

Our findings underscore the importance of learning more about ways to ensure sustainability in donor-financed road safety programming. Research on Vision Zero cities in the United States found that soon after project initiation, government agencies assumed centralized roles in information and resources exchange, with other partners on the periphery (Naumann et al. Citation2019). Our data from Fortaleza and São Paulo suggest that though government agencies form the core of fluid MACs, NGOs can also be central. The maturity of the MAC may also be a factor, where an external international NGO is influential in the relatively newer/smaller Fortaleza network but not in São Paulo. In the case of São Paulo, a local cycling NGO is influential and connected to a vast array of civil society organizations. Thus, we found that though government leadership is essential for multisectoral action, it is not disproportionately represented in both cities. In the case of Fortaleza, this raises some sustainability concerns because the relatively smaller but more cohesive MAC depends on the coordination of a donor-financed international NGO.

We also found scope for improved participation by peripheral actors in both MACs. Highly centralized social networks, with strong top-down planning, run the risk of underutilizing peripheral actors (Merrill et al. Citation2008). This was observed in the denser Fortaleza MAC, with health and traffic actors located on the periphery. In São Paulo, we found that health was also peripheral but traffic agencies were better integrated. Instead, civil society in São Paulo was robustly represented compared to Fortaleza but with little connections to each other or access to decision makers. This implies that future efforts to strengthen road safety programming in Fortaleza should focus on engaging government health and traffic agencies as well as more NGOs. In São Paulo, network density could be enhanced by building linkages between many of the NGOs located on the periphery.

Our data suggest that both networks are expanding, with unclear implications for network performance. Though São Paulo was considered to be older and more established, it demonstrated weaker ties among partners. This can potentially serve as a strength because coordinated activity depends less on the presence of a centralized externally financed international actor. Moreover, networks characterized by less dense and centralized structures over time are potentially sensitive to new ideas and access to emerging resources (Granovetter Citation1973). This underscores the importance of harnessing the array of NGOs in the São Paulo MAC. Though the Fortaleza MAC is seen to be expanding, it remains unclear whether donor transitions or insular thinking will lead to stasis, or even contraction over time, an inherent risk of highly centralized, dense networks (Serri Citation2018).

In addition to network structure, governance, and development characteristics, we generated important insight into the role of data in multisectoral action for road safety. In both MACs, academic partners, particularly in São Paulo, were understood to be peripheral. This is somewhat curious because partners were insistent that data heavily inform programming and policy. A focus on academia, however, is somewhat misleading because much of the data that inform road safety programming are routine data collected by various government and private entities. In both networks, MACs simultaneously voiced support for mortality statistics as well as risk factor data on speed, drink driving, helmet use, and seat belt use, while also pointing to their limitations. Two recommendations concerned moving to more efficient forms of big data processing and focusing on predictive analytics. Equity-oriented considerations from this work would help in prioritizing interventions.

This research provided insight into the sociopolitical mechanics of multisectoral action for road safety in Brazil. Consistent with social network analysis in U.S. cities (Naumann et al. Citation2019), politics enabled MAC formation and performance, though in somewhat different ways, in each city. In Fortaleza, this involved the stability conferred by a strong advocate in the mayor’s office, whereas in São Paulo road safety features somewhat regularly in electoral party politics. Across MACs, actors used the sustainable mobility paradigm (Banister Citation2008) when explaining multisectoral action for road safety. Inherent to this is a more explicit focus on the social dimensions of planning as opposed to the technical aspects of automotive-centric safety. The role that planning plays in relationship-building and collective identity formation was vital to MAC development and is characterized in greater detail in .

Table 3. Planning as a social imperative in road safety MACs.

This research had multiple limitations. First, we did not have the time or resources to survey all relevant employees of a given organization. Instead, following other organizational SNA (Hoe et al. Citation2019; Naumann et al. Citation2019), we used a fixed list sampling scheme to determine leading experts. Second, because it was a cross-sectional study, we were limited in our ability to make claims about changes over time within MACs. Instead, evolution of MACs and their outcomes were based on perceptions of key informants as opposed to observed changes. Similarly, we were not able to adequately characterize sociocultural differences between the 2 cities, which might help explain differences in multisectoral action. Third, as with all qualitative data, much of the phenomena interpreted in this article was situated in particular contexts and may not be generalizable.

In summary, this work leveraged social network analysis to characterize multisectoral action coalitions for road safety in Brazil. More research is needed to capture dynamic processes of change over time and how power imbalances affect MAC sustainability. We argue that bringing attention to organizational processes of road safety coalitions can help ensure that technically sound interventions are better positioned to contribute to a safer and more just society.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (40.3 KB)Additional information

Funding

References

- Andreuccetti G, Leyton V, Carvalho HB, Sinagawa DM, Bombana HS, Ponce JC, Allen KA, Vecino-Ortiz AI, Hyder AA. 2019. Drink driving and speeding in Sao Paulo, Brazil: Empirical cross-sectional study (2015–2018). BMJ Open. 9(8):e030294–8. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030294

- Bachani AM, Peden M, Gururaj G, Norton R, Hyder AA. 2017. Road traffic injuries. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank. Accessed July 30, 2019. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30212112.

- Banister D. 2008. The sustainable mobility paradigm. Transp. Policy. 15(2):73–80. doi:10.1016/j.tranpol.2007.10.005

- Doreian P, Woodard KL. 1992. Fixed list versus snowball selection of social networks. Soc. Sci. Res. 21(2):216–233. doi:10.1016/0049-089X(92)90016-A

- Granovetter MS. 1973. The strength of weak ties. Am. J. Sociol. 78(6):1360–1380. doi:10.1086/225469

- Hoe C, Adhikari B, Glandon D, Das A, Kaur N, Gupta S. 2019. Using social network analysis to plan, promote and monitor intersectoral collaboration for health in rural India. PLoS One. 14(7):e0219786. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0219786

- Hyder AA, Allen KA, Di Pietro G, Adriazola CA, Sobel R, Larson K, Peden M. 2012. Addressing the implementation gap in global road safety: Exploring features of an effective response and introducing a 10-country program. Am. J. Public Health. 102(6):1061–1067. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300563

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística [IBGE]. IBGE Fortaleza Panorama. 2021a. https://cidades.ibge.gov.br/brasil/ce/fortaleza/panorama

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística [IBGE]. IBGE São Paulo Panorama. 2021b. https://cidades.ibge.gov.br/brasil/sp/sao-paulo/panorama

- Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. 2020a. Report on Status of Road Safety Risk Factors in Fortaleza, Brazil, 2019. Baltimore.

- Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. 2020b. Report on Status of Road Safety Risk Factors in São Paulo, Brazil, 2019. Baltimore.

- Kumu. 2020. Kumu help docs. Accessed December 15, 2020. https://docs.kumu.io/guides/metrics.html.

- LaJeunesse S, Heiny S, Evenson KR, Fiedler LM, Cooper JF. 2018. Diffusing innovative road safety practice: A social network approach to identifying opinion leading U.S. cities. Traffic Inj. Prev. 19(8):832–837. doi:10.1080/15389588.2018.1527031

- Marshall C, Rossman GB. 2011. Designing qualitative research. 5th ed. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Merrill J, Caldwell M, Rockoff ML, Gebbie K, Carley KM, Bakken S. 2008. Findings from an organizational network analysis to support local public health management. J Urban Health. 85(4):572–584. doi:10.1007/s11524-008-9277-8

- Ministry of Health [MOH]. 2021. Tabnet Datasus. 2021. http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/ibge/censo/cnv/ginibr.def

- Naumann RB, Heiny S, Evenson KR, LaJeunesse S, Cooper JF, Doggett S, Marshall SW. 2019. Organizational networks in road safety: Case studies of U.S. Vision Zero cities. Traffic Inj. Prev. 20(4):378–385.

- Provan KG, Fish A, Sydow J. 2007. Interorganizational networks at the network nevel: A review of the empirical literature on whole networks. J. Manage. 33(3):479–516.

- QSR International Pty Ltd. (2020) NVivo (released in March 2020), https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home

- StataCorp. 2017. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC

- Serri M. 2018. Social networks and health. Rev. Chil. Infectol. 35(6):629–630. doi:10.4067/S0716-10182018000600629

- SIAT-FOR: Sistema de Informação de Acidentes de Trânsito de Fortaleza [SIAT-FOR]. 2019. Série histórica de vítimas fatais. Fortaleza.

- Sistema de Informações Gerenciais de Acidentes de Trânsito do Estado de São Paulo [INFOSIGA SP]. 2020. Painel de Resultados de Acidentes. Acid. Fatais. Accessed December 11, 2020. http://painelderesultados.infosiga.sp.gov.br/dados.web/ViewPage.do?name=Acidentes_Fatais&contextId=8a80809939587c0901395881fc2b0004.

- Torres C, Sobreira L, Castro-Neto M, Cunto F, Vecino-Ortiz A, Allen K, Hyder A, Bachani A. 2020. Evaluation of pedestrian behavior on mid-block crosswalks: A case study in Fortaleza—Brazil. Front. Sustain. Cities. 2:3. doi:10.3389/frsc.2020.00003

- United Nations. 2020. United Nations Road Safety Collaboration. Decade of Action for Road Safety 2021–2030. Glob. Youth Statement Road Saf. Accessed December 10, 2020. http://www.youthforroadsafety.org/news-blog/news-blog-item/t/united-nations-declares-new-decade-of-action-for-road-safety-2021-2030.

- Valente TW. 2010. Social networks and health: Models, methods and applications. 1st ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Valente TW, Palinkas LA, Czaja S, Chu KH, Hendricks Brown C. 2015. Social network analysis for program implementation. PLoS One. 10(6):e0131712–18. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0131712

- Vias seguras. 2017. Estatísticas do Ministério da Saúde/Estatísticas nacionais/Estatísticas/Os acidentes/Vias Seguras – Vias Seguras. Accessed December 11, 2020. http://vias-seguras.com/os_acidentes/estatisticas/estatisticas_estaduais/estatisticas_de_acidentes_no_estado_de_sao_paulo.

- World Health Organization. 2018. Global status report on road safety. Geneva: World Health Organization.