Abstract

Students and instructors in K-12 and higher education had to quickly transition to remote or online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. This rapid shift was challenging for students, instructors, administrators, and parents across the world. One of the biggest challenges was keeping learners engaged during remote learning due to the physical separation of instructors and students that resulted due to the pandemic. Among the fourteen articles published in this special issue on online learner engagement during COVID-19, three major themes emerged, including: (1) theories and frameworks to engage online learners, (2) characteristics of learners in various educational contexts, and (3) the selection of strategies and provisions of support in the engagement of learners during this quick transition to online or remote learning.

The COVID-19 pandemic created tremendous stress on our educational systems in both K-12 and higher education settings. During this emergency period, both K-12 and higher education instructors shifted quickly from traditional classrooms to remote online teaching and students were suddenly learning in their homes. These remote learning environments and contexts were different from traditional classrooms, which significantly changed the way in which students communicated, engaged, and learned (Xie, Citation2021). Students did not have the needed technologies and resources and might have been unfamiliar with strategies they needed to engage and succeed in emergency online courses. Also, the added stress of the pandemic caused some students to disengage from overall academic activities. In addition, when rapidly moving from face-to-face to emergency remote or online learning, neither learners nor instructors, being separated at a distance, were ready for emergency online learning; therefore, engaging students became a major challenge. This situation presented a need for empirical research to address the unique features of remote and online learning environments, strategies, and support structures as well as understand the unique characteristics of learner engagement (Bolliger & Martin, Citation2018; Martin et al., Citation2018) in these contexts.

While the main focus of this special issue is on students’ perspectives of their engagement in online courses during COVID-19, studies focusing on how instructors adapted quickly to engage their students online as well as parental and family involvement are also included. Researchers use the term emergency remote learning in order to differentiate the rapid shift required by COVID-19 from traditional online teaching (Hodges et al., Citation2020). While our intention is not to choose one term over the other in this special issue, we sought to study how learners engage in rapid online learning during COVID-19. We would like to clarify that emergency remote learning is different from traditional online learning that requires a great deal of pre-planning. Overall, this special issue includes 14 articles pertaining to (1) theories and frameworks to engage online learners during the emergency transition to remote learning, (2) characteristics of learners who engaged in online learning in various contexts during this emergency period, and (3) the selection of strategies and provisions of support in the engagement of learners during this quick transition to online learning.

Emergency remote and online teaching and learning in K-12 schools

Most K-12 schools across the world deliver instruction primarily in the face-to-face format with the exception of virtual schools. However, the COVID-19 pandemic caused a majority of schools to move online rapidly. Teachers, students, and parents were not prepared for this emergency shift to remote teaching and learning. Bozkurt et al. (Citation2020) along with researchers from 30 other countries across the world concluded that though learners were growing up with technology in the 21st century, not many of them participated in online learning for instructional activities prior to the pandemic.

Most of the teacher education programs prepare teachers for face-to-face teaching but do not focus on preparing them for online teaching. While more and more schools are adopting digital resources for teaching, teachers often do not have adequate professional development on how to select and integrate them in classrooms (Bowman et al., Citation2020; Xie et al., Citation2017). During the rapid shift to online teaching, teachers had to be trained quickly and learn how to design lessons for online delivery. In addition, teachers had to be prepared for the facilitation of online courses. Because engaging K-12 learners in a classroom setting is different from engaging them online, teachers had to learn how to engage their learners in online courses. Trust and Whalen (Citation2021) who surveyed K-12 teachers found some of the challenges teachers faced included “accessing, evaluating, learning to use, designing instruction with, and supporting student and family use of technology” (p. 1). Schools had to not only prepare teachers for online teaching but also had to support students with access to digital devices and Internet providers. Some school districts checked out ChromebooksTM to every student, and some sent buses to different parts of the community to provide Internet access to students (Geiger & Dawson, Citation2020).

Parents were overburdened, and there was trauma, psychological pressure, and anxiety. While older students may have been able to adapt and adjust to online learning without parental support, younger learners needed parental involvement (Brown et al., Citation2020; Lawrence & Fakuade, Citation2021). In a survey-based study with K-12 parents in the United States (U.S.), parents reported having difficulties with balancing responsibilities, motivating their children, accessing systems, and addressing learning outcomes due to the shift to remote learning due to COVID-19 (Garbe et al., Citation2020). Lau and Lee (Citation2021) when surveying parents of kindergarten and primary school students in Hong Kong regarding children’s distance education and screen time during COVID-19 determined that children had difficulties with distance learning tasks at home due to lack of interest, home environment limitations, and the inability to participate in learning independently. The use of digital devices was high, and parents were dissatisfied with distance learning and hoped for more interactive learning.

Emergency transition to remote and online teaching and learning in higher education

In comparison to K-12 settings, online teaching and learning has been used in some countries in higher education (Martin et al., Citation2020). However, there was still a great number of instructors who had to shift to online teaching rapidly. Students found themselves facing insecurities relating to basic needs such as housing and food. Some faced financial hardships, uncertainty about the future, a lack of social connectedness and sense of belonging, and access issues that inhibited their well-being and academic performance.

Murphy et al. (Citation2020) surveyed students who transitioned to synchronous virtual classes in the U.S. Students reported their professors utilized the Learning Management System effectively. Instructors adapted quickly, and they communicated course content changes during the transition. However, students experienced negative emotions such as uncertainty, anxiety, and nervousness when they transitioned to virtual classes. Tümen Akyildiz (Citation2020) interviewed undergraduate students in Turkey and determined students had both positive and negative experiences. Negative aspects included anxiety, despair, boredom, and a lack of interaction and communication, which lead to isolation and problems with exams, educational habits, workload, and time management. Tigaa and Sonawane (Citation2020) determined that Internet issues and financial concerns were big concerns in the engagement of students in online chemistry courses. Positive aspects encompassed the flexibility of time and place and students taking responsibility for their own learning.

Some schools transitioned to an asynchronous online format, whereas others transitioned to a synchronous online format. Engaging young adult learners was a challenge in both online learning formats (Murphy et al., Citation2020). Lowenthal et al. (Citation2020) described the experiences of four instructors using asynchronous videos rather than synchronous lectures to engage and connect with their students. This strategy was recommended to avoid the overuse of synchronous tools but at the same time provide flexibility to learners.

Engagement in online teaching and learning during the COVID-19 pandemic

One of the challenges during the emergency transition to online learning was the engagement of students. In K-12, teachers were used to having most of the instruction delivered in a face-to-face format; therefore, they were familiar with strategies to engage students in person. Learner engagement is a multifaceted concept and is described as the involvement of learners in their learning (Bolliger & Martin, Citation2021). Learner engagement also describes varied learner aspects including beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors (Redmond et al., Citation2018; Rodgers, Citation2008) focusing on behavioral, cognitive, and affective dimensions. Fredricks et al. (Citation2004) initially examined engagement through behavioral, cognitive, and emotional aspects. They later included social engagement as an additional dimension.

While learner engagement has been studied for years, literature on online learner engagement is still evolving. Transactional distance with the separation of the learner and the instructor in space and time adds another hurdle to engagement, and an extra effort needs to be made to increase the amount of dialogue, structure, and autonomy between course participants (Moore, Citation1993). Martin et al. (Citation2020) in a recent synthesis of the literature on online learning created the following categories for online engagement: interaction, presence, communication, collaboration, community, and participation.

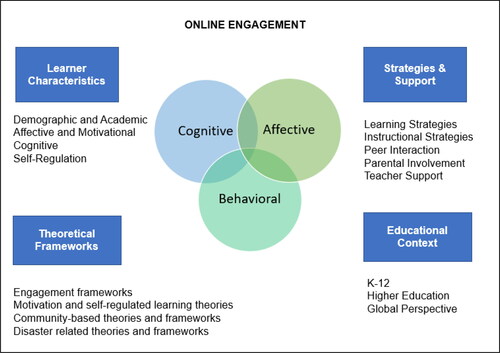

While the research on learner engagement typically centers on the key facets of engagement, the literature acknowledges that learner engagement is a complex issue and often involves multiple elements within the educational system and from different contexts. visualizes the major themes that emerged from the studies included in this special issue including theories and frameworks, learner characteristics, strategies and support, and educational context.

Theories and frameworks

One major theme that emerged from the research articles included in this special issue is related to the breadth of theoretical lenses used in these studies. While this special issue particularly calls for research focused on learner engagement, a wide range of theories and frameworks were used in guiding the investigations of learner engagement. These theories and frameworks cover four major topics representing the focus of this special issue, including engagement frameworks, motivation and self-regulated learning theories, community-based theories and frameworks, and disaster-related theories and frameworks. Some articles include multiple theories and frameworks.

Generally, engagement frameworks position engagement as a complex and multidimensional construct. Frameworks focusing on the psychological processes conceptualize engagement including behavioral, cognitive, and affective aspects (e.g., Fredricks et al., Citation2004). Behavioral engagement typically focuses on students’ learning behaviors such as effort, persistence, attention, and concentration. Cognitive engagement focuses on the cognitive processes of learning such as the applications of deep or shallow strategies during learning activities. Affective engagement, on the other hand, focuses on students’ feelings toward learning activities, such as positive or negative emotions. Later, additional dimensions such as social engagement focusing on interactions and collaborations among peers (e.g., Fredricks et al., Citation2016; Xie et al., Citation2020) and agentic engagement focusing on students’ agency and self-determination for learning tasks (e.g., Reeve, Citation2013) were included in this engagement framework. This framework has also been extended to higher education (Kahu, Citation2013) and modalities such as blended learning (Borup et al., Citation2020) and mobile learning (Xie et al., Citation2019).

In contrast, transactional distance theory (Moore, Citation1991) explains learner engagement through the mechanism in which interactions occur in distance settings. Martin and Bolliger (Citation2018) built upon the transactional distance theory to describe learner engagement in online learning. Their conceptualization was initiated using learner-to-learner interaction, learner-to-instructor interaction, and learner-to-content interaction and a factor analysis of their instrument resulted in peer engagement, instructor engagement, self-directed engagement, and multi-modal engagement as major engagement factors in online learning. While the majority of the articles in this special issue adopted the psychological dimensions of engagement (Aladsani, Citation2022; Chiu, Citation2022; Kara, Citation2022; Roman et al., Citation2022; Rutherford et al., Citation2022; Yang et al., Citation2022), few studies were based on the interactional dimensions of engagement (e.g., Hensley et al., Citation2022). A few studies treated engagement as a general construct (e.g., Kurt et al., Citation2022; Stewart & Lowenthal, Citation2022; Wagner, Citation2022).

The second group of theories and frameworks address the motivational and self-regulatory processes of learning. Motivational research focuses on reasons that drive engaged behaviors. Chiu (Citation2022) adopted Self-Determination Theory (Deci & Ryan, Citation1985) to explain students’ motivation. This theory draws the distinction between intrinsic motivation (e.g., interest and enjoyment) and extrinsic motivation (e.g., rewards and punishment). It also highlights the importance of satisfying three basic psychological needs (i.e., autonomy, competency, and relatedness). The study results support that students’ self-reported need satisfaction influences their behavioral, emotional, cognitive, and agentic engagement.

Two studies (Hilpert et al., Citation2022; Rutherford et al., Citation2022) examined academic motivation based upon the Expectancy-Value Theory (Eccles et al., Citation1983) that highlights the role of value, associated cost, and expectancy for success in driving students’ engagement. When students believe the academic tasks are interesting, useful, and important, when they expect to succeed in the tasks, and when they perceive lower costs of the tasks (e.g., effort, time, stress), then they are most likely to engage in such tasks. In addition, academic motivation is often associated with learners’ self-regulation of learning; therefore, several studies adopted both motivation theories and self-regulated learning frameworks in examining learner engagement. For example, Hilpert et al. (Citation2022) examined how motivation and self-regulation of learning influenced students’ engagement during the pandemic. Hensley et al. (Citation2022) situated motivation as a part of self-regulated learning processes (Pintrich, Citation2004) and examined the complex relationships between motivation, engagement, and self-regulation in learning through a qualitative methodology. On the other hand, Kara (Citation2022) examined similar topics in a different context in Turkey using frameworks of self-directed learning that are in the adult learning literature (e.g., Dray et al., Citation2011; Pemberton & Cooker, Citation2012).

The third group of theories and frameworks focus on communities of online learning. The Community of Inquiry framework (CoI) (Garrison et al., Citation1999) describes essential components of a meaningful and engaging learning experience including social presence, cognitive presence, and teaching presence. This framework provides fundamental guidelines for the design of distance education courses. For example, Kurt et al. (Citation2022) applied the CoI theoretical lens in guiding their qualitative interpretation. Wagner (Citation2022) also highlighted the importance of learning communities in examining online teacher inquiry. Roman et al. (Citation2022) adopted the Academic Communities of Engagement framework (Borup et al., Citation2020) in their analysis of learner engagement with learning communities. Dennen et al. (Citation2022) applied the four roles of the online instructor framework in the exploration of a team-teaching approach during the pandemic. The framework stresses the important role of instructors in supporting learners’ social needs in a community.

The last group of theories and frameworks deal with disaster related topics such as trauma and disaster management. Roman et al. (Citation2022) adopted the Trauma-Informed Teaching and Learning Principles in the discussion of supporting learner engagement during the pandemic. These principles cover seven essential topics in dealing with trauma including physical, emotional, social, and academic safety; trustworthiness and transparency; support and connection; collaboration and mutuality; empowerment, voice, and choice; social justice and resilience; and growth and change (Carello, Citation2020). In exploring a distributed team-teaching approach during the pandemic, Dennen et al. (Citation2022) applied the disaster management cycle (Alexander, Citation2002) as a framework in guiding the instructional design processes dealing with the emergency transition to remote learning. The disaster management cycle includes four phases: preparedness, response, recovery, and mitigation.

Learner characteristics

COVID-19 impacted a wide range of learners. This is reflected in the wide variety of learner characteristics that were addressed by authors in this special issue. We used the classification of Martin et al. (Citation2020) who conducted a systematic review of online teaching and learning articles to categorize these learner characteristics. These categories are: demographic and academic, affective and motivational, cognitive, and self-regulation characteristics.

Several authors (Aladsani, Citation2022; Chiu, Citation2022; Dennen et al., Citation2022; Kara, Citation2022; Killham et al., Citation2022; Rutherford et al., Citation2022; Stewart & Lowenthal, Citation2022; Wagner, Citation2022; Yang et al., Citation2022) looked at the impact of demographics and academic characteristics. Demographics are descriptive data, whereas academic characteristics can be described as skills that contribute to students’ success or relate to their academic preparation or readiness. Elements included in these categories were academic major, age, competence, digital literacy, exchange student status, first-generation college students, grade level, gender, previous online learning experience, race, socio-economic status (e.g., family income, financial burden, free or reduced lunch), second language learners, special needs, technology access, and time zones.

Affective characteristics can be described as emotions such as anxiety or fear, and motivation can center around goals or persistence. Aladsani (Citation2022), Chiu (Citation2022), Dennen et al. (Citation2022), Hensley et al. (Citation2022), Hilpert et al. (Citation2022), Kara (Citation2022), Kurt et al. (Citation2022), Luo et al. (Citation2022), Roman et al. (Citation2022), Rutherford et al. (Citation2022), Stewart and Lowenthal (Citation2022), Wagner (Citation2022), and Yang et al. (Citation2022) investigated elements in this special issue that pertained to attitudes, confidence, emotional cost (e.g., frustrations), interests, isolation, emotions (e.g., anger), emotional needs (e.g., connectedness, belonging), psychological needs (e.g., comfort and safety), relatedness, feelings of stress, social competence, and social support needs (e.g., interaction and peer learning). Five authors (Hensley et al., Citation2022; Hilpert et al., Citation2022; Kara, Citation2022; Kurt et al., Citation2022; Rutherford et al., Citation2022) addressed overall student motivation.

Cognitive characteristics refer to brain-based processes that guide the behavior of individuals such as attention, memory or logic. Dennen et al. (Citation2022), Hensley et al. (Citation2022), and Wagner (2022) focused on students’ learning needs, strategies or support.

Lastly, self-regulation characteristics—the ability to observe and manage one’s behaviors—were examined by Chiu (Citation2022), Dennen et al. (Citation2022), Hensley et al. (Citation2022), Hilpert et al. (Citation2022), Kara (Citation2022), Kurt et al. (Citation2022), and Yang et al. (Citation2022). They explored behaviors such as autonomy, cost (e.g., effort, stress, and opportunities), time spent on online coursework, responsibilities, self-efficacy, self-directed or self-regulated learning, and self-regulation of stress.

Strategies and support structures

Another research theme among the articles in this special issue is strategies used and support required to engage online learners during COVID-19. Because the pandemic impacted several aspects of learner engagement, additional strategies and support structures had to be quickly put in place for online learning. Some of the studies examined learning and instructional strategies, peer interaction, parental involvement, and teacher support. Teacher support focused on support for new instructors as well as professional development for seasoned teachers. The articles in this special issue describe several strategies and support structures, and each article highlights strategies and support structures utilized and recommended.

Wagner (2022) examined K-5 teacher perspectives on pedagogies and support structures to sustain student learning online. Six elementary school teachers in the U.S. were interviewed for this study. During COVID-19, all participating school districts provided the students with computers or tablets for remote learning. The teachers recommended a variety of pedagogies and the importance of providing choices including multiple learning structures such as incorporating song, movement, artmaking with verbal responses, and composing responses by writing in Google Docs which provides multiple ways for children to engage in learning. This was to prevent students from experiencing online burnout or remote learning fatigue and provided the mental break needed to both students and teachers. Teachers also recommended the use of a variety of synchronous and asynchronous formats, including informal spaces for community building. Synchronous spaces support community building and the formation of relationships with peers and teachers and assist with socio-emotional learning. For support structures, teachers identified policies for student engagement and performance as critical for student achievement, and they reported conflicts with their administration over student privacy issues limiting the use of technology. Teachers also discussed the importance of parental support and the need for parent training to support their children during remote learning.

In another study with young children in China, Luo et al. (Citation2022) studied young children’s peer interactions through five short video recordings on a publicly available open-access social media platform during the initial days of the pandemic. Results of the video analysis showed that play materials and tangible tools play an important role in mediating young children’s peer interactions and participation in remote learning. Children also used multimodal communication strategies such as verbal and nonverbal discourse and mediated actions through materials and tools. On studying middle school students and their parents in eight socioeconomically advantaged middle schools in China, Yang et al. (Citation2022) concluded that higher levels of parental involvement and teacher support resulted in higher levels of student affective engagement. Yang et al. also found that teacher support had the strongest relationship with student engagement. Students stated that teachers supported them by providing explicit learning objectives, presenting course materials in a thoughtful way, and encouraging students to learn. Although parent involvement was critical for student affective engagement, Yang et al. found that only a small percentage of parents were involved in their child’s online learning. Students who responded to the survey were not mentally ready for online learning, as it was new for K-12 students in China prior to the pandemic.

Dennen et al. (Citation2022) discuss how a distributed team approach was used to support four instructors who were graduate students teaching different sections of a technology course for 70 undergraduate preservice teachers. The instructors used a common syllabus and assignments, and instructors and one mentor redesigned the course quickly to include flexibility and engagement opportunities when the pandemic started. A student check-in survey was distributed to identify students’ basic needs, stress levels, technology access, comfort with online learning, time zone constraints, and instructor support at the onset of the pandemic. This feedback provided the data for the design of the course with flexibility for the students. Collaborative course development minimized pedagogical and technological tasks and reduced instructors’ stress and isolation providing them with time to focus on student engagement and meet social and administrative needs.

Roman et al. (Citation2022) explain how a professional development workshop in the summer of 2020 guided by trauma-informed teaching practices and learner engagement conceptual frameworks resulted in 11 teachers paying more attention to affective and social dimensions of learner engagement. With the onset of COVID-19, the results of a survey showed that while teachers were confident in engaging students with technology during face-to-face teaching, they experienced challenges in remote settings due to the students’ lack of access to technology and the absence of a learning platform to support interaction. While they initially prioritized behavioral engagement during COVID-19 in Spring 2020, they increased their focus on social and affective engagement indicators in Fall 2020. Teachers expressed a commitment to social justice and infused trauma-informed principles such as physical, emotional, social, and academic safety intentionally in their teaching. Strategies they valued included building rapport with students using icebreaker activities, using one-to-one virtual conferences, providing a safe learning environment, and supporting student learning and academic success.

Kurt et al. (Citation2022) interviewed 20 students in Turkey. Students perceived that teachers’ teaching style and practice; students’ academic motivation, self-regulation and attitudes; the learning environment; and policies impacted their engagement. From the analysis of interviews with 22 teachers, Kurt et al. found that sufficiency and relevancy of online materials; students’ willingness to learn; self-regulatory behaviors and emotional states; the learning environment; and policies impacted student engagement. Some of the recommendations include designing and implementing engaging tasks and activities, focusing on familiar topics, and applying interactive teaching techniques in order to enhance online student engagement.

Similarly, Aladsani (Citation2022) in a Saudi Arabian context discusses synchronous online teaching by six female instructors. Encouraging student interaction during lectures and in discussion forums, referring to students by their names, and allocating points for participation were strategies that worked well during the rapid shift to remote learning. In addition, it was important for instructors to exhibit high levels of digital empathy and provide emotional support to their students.

Stewart and Lowenthal (Citation2022) conducted a case study with 15 international exchange students who were in South Korea. They determined that some students benefited from learning online. Students enjoyed learning from home, more flexible schedules, and learning when it was most convenient. However, there were challenges that included the lack of interaction with other students and instructors, lack of uniformity in types of courses, participation in long synchronous sessions, and the use of prerecorded lectures. Students encountered cultural and language differences, and they completed courses in small dorm rooms with roommates present while struggling with loneliness, stress, and mental well-being. Killham et al. (Citation2022) identified family input, routines, and effective communication as critical factors for first-generation undergraduate Latina college students to succeed during remote learning. Family input focused on the role families played in their lives, balancing new living arrangements, stepping up to be caregivers during the pandemic. They also had to identify new routines to manage tasks and workload as it was altered by the remote learning environment. Effective communication was critical as it differed in remote learning settings, and they had to find new ways for their voices to be heard, and also explain roles other individuals played to create new lines of communication.

Global perspectives on engaging online learners during the pandemic

Seven studies in the special issue were conducted in the U.S., and another seven studies were conducted in various countries including Turkey, Mainland China, Hong Kong, South Korea, and Saudi Arabia. These studies provide a perspective on online engagement during COVID-19 from Asia and the Middle East. Most institutions in these countries made an emergency transition to remote learning in K-12 and higher education contexts.

Kurt et al. (Citation2022) studied student engagement in K-12 online education in Turkey by interviewing teachers and students. In March 2020, 16 million Turkish students and 800,000 teachers at K-12 schools shifted to online education. With the assistance of Internet- and TV-based instruction, videos of Turkish teachers lecturing were aired. Additionally, they used a nationwide Ministry of National Education system through which teachers uploaded learning materials and assignments and began teaching synchronous online classes. When the researchers interviewed 20 students and 22 teachers, they identified instructional, cognitive, and affective factors in addition to learning environment and policy as major themes.

In Saudi Arabia, Aladsani (Citation2022) examined the stories of six female university instructors using a narrative approach. The rapid transition to online learning posed a challenge for both instructors and students who were anxious because of the pandemic and a curfew that impacted teaching and learning. In addition, cultural challenges faced by female instructors from having to cover their faces in front of non-related men affected instructors in their teaching. They feared that the absence of body language and facial expressions would negatively impact student engagement. The instructors’ stories included feelings during the transition, challenges they faced, and their efforts to engage their students.

In China, Yang et al. (Citation2022) administered a cross-sectional survey to study parental involvement, teacher support, and students’ affective engagement across eight middle schools. By surveying 1550 students with a linked parental survey, they found that students on average spent 3.8 hours per day in online courses provided by their teachers, which was approximately 50% less time spent in face-to-face classes at school. They concluded when higher levels of parental involvement and teacher support exist, it will result in higher levels of student affective engagement. In another study from China, Luo et al. (Citation2022) studied young children’s peer interaction and social competence development on Douyin, a publicly available open-access platform to share videos with a vast audience. They determined that play materials and tangible tools were critical for young children’s peer interaction and participation in remote learning.

In South Korea, Stewart and Lowenthal (Citation2022) describe the experience of 15 foreign exchange students through in-person interviews but still following the safety protocol which included face masks, hand sanitizers, and lavalier microphones with a 2-meter cable connected to a smartphone to maintain physical distance between the interviewer and interviewee. Foreign exchange students were from Belgium, Brazil, Columbia, France, Mexico, Spain, and Turkey majoring in various disciplines. While seven students had a roommate, others lived alone. Their interviews revealed both positive and negative experiences and included themes of isolation and loneliness, diverse learning experiences, and limited social interaction during this experience.

In the U.S., most K-12 schools and higher education institutions shifted to remote learning in March 2020. Wagner (2022) describes how a school district supplied children with computers or tablets during remote teaching. In this study, several data sources were analyzed to identify pedagogies and support structures to engage PK-5 learners: video recordings and group chat records, facilitator field notes, teacher journals, and interview data. Hensley et al. (Citation2022) describe how a university transitioned from a traditional semester to remote teaching after spring break when students were allowed to move off campus. Instructors had to change their instructional delivery to remote education for the remainder of the semester. Instructors reported they used new instructional strategies for synchronous and asynchronous online instruction along with new university policies for grading. Killham et al. (Citation2022) examined first-generation undergraduate Latina college student’s tenacity during remote learning analyzing narratives.

provides the list of articles in this special issue including the context and the region where the study was conducted.

Table 1. Context and region of articles published in this special issue.

Implications

Research on online engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic showed how our education system is resilient and how dedicated teachers are in supporting students. Teachers adapted quickly to meet the needs of their various learners, although their workload drastically increased, particularly for those who taught online for the first time (Naidu, Citation2021). Yet, there were various challenges that students, teachers, and parents faced. It was evident that not all instructors were prepared, not all students had the resources to participate in online learning, and parents had to be involved in the education of their young children while juggling other responsibilities at home and work. K-12 teachers and university instructors had to be quickly trained to teach online (Hartshorne et al., Citation2020). They also focused on how to support students holistically. They were not only concerned about students’ learning needs but also very basic needs such as safety, food, and housing (Martel, Citation2020).

The studies in the special issue have the following implications.

Professional development is essential for teachers to engage learners.

Providing K-12 learners who may not have access to the technology with computers or tablets is critical to engage them.

Teachers and instructors need to utilize a variety of pedagogies and resources such as play materials and tangible tools to engage young learners.

Teachers and instructors should use a variety of synchronous and asynchronous formats, including informal spaces for community building during remote learning.

Parent training is important to prepare them to engage their children.

A collaborative teaching approach to course development assists novice instructors.

Trauma-informed teacher training assists instructors in focusing on affective and social dimensions of learner engagement.

Designing and implementing engaging tasks and activities, focusing on familiar topics, and applying interactive teaching techniques enhance online student engagement.

Encouraging student interaction during lectures, student participation in discussion forums, referring to students by their names, and allocating points for participation engages students.

Family input, routines and effective communication are essential for the success of first-generation college students.

While online learning has benefits such as working from home, flexibility, and a self-paced schedule, it also comes with challenges such as loneliness and stress, and a concern for mental well-being.

Future direction

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed the landscape of education forever. If and when we go back to normal, how our education system will look is a big question to which we await the answer. Sustaining the impact of COVID-19 in education can be negative yet also positive. When COVID-19 spread, educational systems were not prepared. School closures widened the learning gap especially for children of families with lower socioeconomic backgrounds who fell behind due to the lack of technology and support. Assessments were canceled (Burgess & Sievertsen, Citation2020). Schools and universities had to ramp up and struggled to support teachers, parents, and students. Now that the system is in place, we can expand on it to be prepared should another global emergency arise. COVID-19 has changed schools and educational systems, but we hope that the benefits of emergency remote or online learning outweigh its disadvantages. Perhaps the education system across all levels–even beyond the pandemic–can continue to utilize innovative approaches, strategies, and tools to provide learners of all ages with flexibility and opportunities (Nworie, Citation2021).

COVID-19 has changed how students engage in learning activities. Schools and universities have provided an online learning infrastructure, professional development for students and instructors, parent training for those with young children where parental support was critical, and international collaborations in building a sustainable educational system. Initially, instructors and students had to struggle because they did not have the skills to be successful in blended or online learning and teaching environments. It was a struggle to acquire these skills even if they were limited. Now that they have acquired some of these skills, they can build on them by participating in additional professional development workshops or training. We hope we will remember the lessons learned and continue to overcome the challenges we face.

References

*Articles included in the special issue

- *Aladsani, H. K. (2022). A narrative approach to university instructors’ stories about promoting student engagement during COVID-19 emergency remote teaching in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 54(S1), S165–S181. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2021.1922958

- Alexander, D. (2002). Principles of emergency planning and management. Oxford University Press.

- Bolliger, D. U., & Martin, F. (2018). Instructor and student perceptions of online student engagement strategies. Distance Education, 39(4), 568–583. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2018.1520041

- Bolliger, D. U., & Martin, F. (2021). Factors underlying the perceived importance of online student engagement strategies. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 13(2), 404–419. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JARHE-02-2020-0045

- Borup, J., Graham, C. R., West, R. E., Archambault, L., & Spring, K. J. (2020). Academic communities of engagement: An expansive lens for examining support structures in blended and online learning. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68(2), 807–832. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09744-x

- Bowman, M. A., Vongkulluksn, V. W., Jiang, Z., & Xie, K. (2020). Teachers’ exposure to professional development and their use of instructional technology: The mediating role of teachers’ value and ability beliefs. Journal of Research on Technology in Education. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2020.1830895

- Bozkurt, A., Jung, I., Xiao, J., Vladimirschi, V., Schuwer, R., Egorov, G., Lambert, S. R., Al-Freih, M., Pete, J., Olcott Jr., D., Rodes, V., Aranciaga, I., Bali, M., Alvarez Jr., A. V., Roberts, J., Pazurek, A., Raffaghelli, J. E., Panagiotou, N.; de Coëtlogon, P., Shahadu, S., Brown, M., Asino, T. I., Tumwesige, J., Ramirez Reyes, T., Barrios Ipenza, E., Ossiannilsson, E., Bond, M., Belhamel, K., Irvine, V., Sharma, R. C., Adam, T., Janssen, B., Sklyarova, T., Olcott, N., Ambrosino, A., Lazou, C., Mocquet, B., Mano, M., Paskevicius, M. ( 2020). A global outlook to the interruption of education due to COVID-19 pandemic: Navigating in a time of uncertainty and crisis. Asian Journal of Distance Education, 15(1), 1–126. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3878572

- Brown, S. M., Doom, J. R., Lechuga-Peña, S., Watamura, S. E., & Koppels, T. (2020). Stress and parenting during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Child Abuse & Neglect, 110(Part2), 104699. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104699

- Burgess, S., Sievertsen, H. H. (2020, April 1). Schools, skills, and learning: The impact of COVID-19 on education. VoxEU: Centre for Economic Policy Research. https://voxeu.org/article/impact-covid-19-education

- Carello, J. (2020, March). Trauma-informed teaching and learning principles. https://traumainformedteachingblog.files.wordpress.com/2020/04/titl-general-principles-3.20.pdf

- *Chiu, T. K. F. (2022). Applying the self-determination theory (SDT) to explain student engagement in online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 54(S1), S14–S30. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2021.1891998

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Springer.

- *Dennen, V. P., Bagdy, L. M., Arslan, Ö., Choi, H., & Liu, Z. (2022). Supporting new online instructors and engaging remote learners during COVID-19: A distributed team teaching approach. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 54(S1), S182–S202. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2021.1924093

- Dray, B. J., Lowenthal, P. R., Miszkiewicz, M. J., Ruiz‐Primo, M. A., & Marczynski, K. (2011). Developing an instrument to assess student readiness for online learning: A validation study. Distance Education, 32(1), 29–47. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2011.565496

- Eccles, J., Adler, T. F., Futterman, R., Goff, S. B., Kaczala, C. M., Meece, J., & Midgley, C. (1983). Expectancies, values and academic behaviors. In J. T. Spence (Ed.), Achievement and achievement motives: Psychological and sociological approaches (pp. 75–146). W. H. Freeman.

- Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59–109. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074001059

- Fredricks, J. A., Filsecker, M., & Lawson, M. A. (2016). Student engagement, context, and adjustment: Addressing definitional, measurement, and methodological issues [Editorial]. Learning and Instruction, 43, 1–4. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.02.002

- Garbe, A., Ogurlu, U., Logan, N., & Cook, P. (2020). COVID-19 and remote learning: Experiences of parents with children during the pandemic. American Journal of Qualitative Research, 4(3), 45–65. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.29333/ajqr/8471

- Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (1999). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2-3), 87–105. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00016-6

- Geiger, C., & Dawson, K. (2020). Virtually PKY - How one single-school district transitioned to emergency remote instruction. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 28(2), 251–260. https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/216187

- Hartshorne, R., Baumgartner, E., Kaplan-Rakowski, R., Mouza, C., & Ferdig, R. E. (2020). Special issue editorial: Preservice and inservice professional development during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 28(2), 137–147. https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/216910/

- *Hensley, L. C., Iaconelli, R., & Wolters, C. A. (2022). This weird time we’re in”: How a sudden change to remote education impacted college students’ self-regulated learning. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 54(S1), S203–S218. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2021.1916414

- *Hilpert, J. C., Bernacki, M. L., & Cogliano, M. (2022). Coping with the transition to remote instruction: Patterns of self-regulated engagement in a large post-secondary biology course. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 54(S1), S219–S235. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2021.1936702

- Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T., Bond, A. (2020, March 27). The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. EDUCAUSE Review. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning

- Kahu, E. R. (2013). Framing student engagement in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 38(5), 758–773. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.598505

- *Kara, M. (2022). Revisiting online learner engagement: Exploring the role of learner characteristics in an emergency period. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 54(S1), S236–S252. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2021.1891997

- *Killham, J. E., Estanga, L., Ekpe, L., & Mejia, B. (2022). The strength of a tigress: An examination of Latina first-generation college students’ tenacity during the rapid shift to remote learning. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 54(S1), S253–S272. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2021.1962450

- *Kurt, G., Atay, D., & Öztürk, H. A. (2022). Student engagement in K12 online education: The case of Turkey. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 54(S1), S31–S47. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2021.1920518

- Lau, E. Y. H., & Lee, K. (2021). Parents’ views on young children’s distance learning and screen time during COVID-19 class suspension in Hong Kong. Early Education and Development, 32(6), 863–880. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2020.1843925

- Lawrence, K. C., & Fakuade, O. V. (2021). Parental involvement, learning participation and online learning commitment of adolescent learners during the COVID-19 lockdown. Research in Learning Technology, 29, 1–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.25304/rlt.v29.2544

- *Luo, W., Berson, I. R., Berson, M. J., & Han, S. (2022). Young Chinese children’s remote peer interactions and social competence development during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 54(S1), S48–S64. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2021.1906361

- Lowenthal, P., Borup, J., West, R., & Archambault, L. (2020). Thinking beyond Zoom: Using asynchronous video to maintain connection and engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 28(2), 383–391. https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/216192

- Martel, M. (2020, May). COVID-19 effects on US higher education campuses: From emergency response to planning for future student mobility. Institute of International Education. https://www.iie.org/Research-and-Insights/Publications/COVID-19-Effects-on-US-Higher-Education-Campuses-Report-2

- Martin, F., & Bolliger, D. U. (2018). Engagement matters: Student perceptions on the importance of engagement strategies in the online learning environment. Online Learning, 22(1), 205–222. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v22i1.1092

- Martin, F., Sun, T., & Westine, C. D. (2020). A systematic review of research on online teaching and learning from 2009 to 2018. Computers & Education, 159, 104006. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2020.104009

- Martin, F., Wang, C., & Sadaf, A. (2018). Facilitation matters: Instructor perception of helpfulness of facilitation strategies in online courses. Online Learning, 24(1), 28–49. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v24i1.1980

- Moore, M. G. (1991). Distance education theory [Editorial]. American Journal of Distance Education, 5(3), 1–6. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08923649109526758

- Moore, M. G. (1993). Theory of transactional distance. In D. Keegan (Ed.), Theoretical principles of distance education (pp. 22–38). Routledge.

- Murphy, L., Eduljee, N. B., & Croteau, K. (2020). College student transition to synchronous virtual classes during the COVID-19 pandemic in northeastern United States. Pedagogical Research, 5(4), 1–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.29333/pr/8485

- Naidu, S. (2021). Building resilience in education systems post-COVID-19 [Editorial]. Distance Education, 42(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2021.1885092

- Nworie, J. (2021, May 19). Beyond COVID-19: What’s next for online teaching and learning in higher education? Educause Review. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2021/5/beyond-covid-19-whats-next-for-online-teaching-and-learning-in-higher-education

- Pemberton, R., & Cooker, L. (2012). Self-directed learning: Concepts, practice, and a novel research methodology. In S. Mercer, S. Ryan, & M. Williams (Eds.), Psychology for language learning: Insights from research, theory and practice (pp. 203–219). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Pintrich, P. R. (2004). A conceptual framework for assessing motivation and self-regulated learning in college students. Educational Psychology Review, 16(4), 385–407. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-004-0006-x

- Redmond, P., Abawi, L.-A., Brown, A., Henderson, R., & Heffernan, A. (2018). An online engagement framework for higher education. Online Learning, 22(1), 183–204. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v22i1.1175

- Reeve, J. (2013). How students create motivationally supportive learning environments for themselves: The concept of agentic engagement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(3), 579–595. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032690

- Rodgers, T. (2008). Student engagement in the e-learning process and the impact on their grades. International Journal of Cyber Society and Education, 1(2), 143–156. http://academic-pub.org/ojs/index.php/IJCSE/article/view/519/247

- *Roman, T. A., Brantley-Dias, L., Dias, M., & Edwards, B. (2022). Addressing student engagement during COVID-19: Secondary STEM teachers attend to the affective dimension of learner needs. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 54(S1), S65–S93. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2021.1920519

- *Rutherford, T., Duck, K., Rosenberg, J. M., & Patt, R. (2022). Leveraging mathematics software data to understand student learning and motivation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 54(S1), S94–S131. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2021.1920520

- *Stewart, W. H., & Lowenthal, P. R. (2022). Distance education under duress: A case study of exchange students’ experience with online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Republic of Korea. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 54(S1), S273–S287. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2021.1891996

- Tigaa, R. A., & Sonawane, S. L. (2020). An international perspective: Teaching chemistry and engaging students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Chemical Education, 97(9), 3318–3321. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00554

- Trust, T., & Whalen, J. (2021). K-12 teachers’ experiences and challenges with using technology for Emergency Remote Teaching during the Covid-19 pandemic. Italian Journal of Educational Technology, 29(2), 10–25. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17471/2499-4324/1192

- Tümen Akyildiz, S. (2020). College students’ views on the pandemic distance education: A focus group discussion. International Journal of Technology in Education and Science, 4(4), 322–334. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.46328/ijtes.v4i4.150

- *Wagner, C. J. (2022). PK-5 teacher perspectives on the design of remote teaching: Pedagogies and support structures to sustain student learning online. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 54(S1), S132–S147. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2021.1888340

- Xie, K. (2021). Projecting learner engagement in remote contexts using empathic design. Educational Technology Research and Development, 69(1), 81–85. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09898-8

- Xie, K., Heddy, B. C., & Vongkulluksn, V. W. (2019). Examining engagement in context using experience-sampling method with mobile technology. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 59, 101788. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2019.101788

- Xie, K., Kim, M. K., Cheng, S.-L., & Luthy, N C. (2017). Teacher professional development through digital content evaluation. Educational Technology Research & Development, 65(4), 1067–1103. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-017-9519-0

- Xie, K., Vongkulluksn, V W., Lu, L., & Cheng, S.-L. (2020). A person-centered approach to examining high-school students’ motivation, engagement and academic performance. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 62, 101877. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101877

- *Yang, Y., Liu, K., Li, M., & Li, S. (2022). Students’ affective engagement, parental involvement, and teacher support in emergency remote teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from a cross-sectional survey in China. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 54(S1), S148–S164. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2021.1922104