Abstract

Speaking with an artificial counterpart in simulated environments has been shown beneficial for foreign language learning. Still, few studies have explored how it is experienced by younger students. We report on a study of Swedish students (N = 22) speaking English with embodied conversational agents (ECAs) in everyday-life scenarios. Data were collected on students’ rankings, choices, and open-response items in logbooks and questionnaires. Self-reported data on experiences were analyzed through three dimensions: cognitive, emotional, and social. Findings show that students were generally satisfied with the activity and emotionally engaged with large individual differences within the social dimension. We unpack aspects regarding social relating to the ECA, analyzing the space between experiencing the ECA as a socially distant “deadpan machine” to humanizing and relating socially.

Introduction

There are recognized challenges in foreign language learning of speaking due to a lack of meaningful opportunities to practice speaking skills and receive feedback because of practical and physical constraints in class (Timpe-Laughlin et al., Citation2022). Learning speaking skills comes with unique cognitive challenges due to their complexity, which for many students, provoke anxiety (Goh & Burns, Citation2012). The issue of providing interactive language learning opportunities can be addressed through the use of conversational artificial intelligence (AI) in that they enable students to engage in authentic interaction in simulated environments with interlocutors in the target language (e.g. Bibauw et al., Citation2022; Johnson, Citation2019). The main purpose of this paper is to expand understanding of how middle school students experience that kind of speaking activity.

Conversational AI employs natural language processing and automatic speech recognition in computer-driven spoken dialogue systems (SDSs; Divekar et al., Citation2021; McTear, Citation2020). An SDS supports interaction with humans through voice-based chatbots (Huang et al., Citation2022; Masche & Le, Citation2018) or system-controlled embodied conversational agents (ECAs; Bickmore & Cassell, Citation2005; McTear, Citation2020) as interlocutors for practising speaking skills (e.g. Ayedoun et al., Citation2019). Another type of humanlike agents also referred to in alignment with their function in a system, are animated pedagogical agents for facilitating learning, mostly lecturing in one-way (Schroeder et al., Citation2013). These agents in educational technology environments also go by the name virtual humans (Burden & Savin-Baden, Citation2019; Craig & Schroeder, Citation2018; Schroeder & Craig, Citation2021). Since there is some overlap between ECAs and virtual humans in the social aspect of generating social agency, we include studies from these fields, although the employed agents in the study reported on in this paper were ECAs.

Practicing speaking with ECAs in everyday-life conversational simulations is a recognized method to facilitate the development of speaking and listening skills (Bibauw et al., Citation2022; Divekar et al., Citation2021; Golonka et al., Citation2014). Spoken interaction with ECAs occurs in a low-anxiety environment where the students feel safe while improving their willingness to communicate (Ayedoun et al., Citation2019; Huang et al., Citation2022) and boosting motivation (Anderson et al., Citation2008; Ebadi & Amini, Citation2022). Experiencing a social relationship with such systems might possibly influence students’ learning results (Walker & Ogan, Citation2016). Social cues have been explored in other fields around conversational AI and the efficacy of embodiment features of agents, such as virtual humans, on learning and performance (Craig & Schroeder, Citation2018; Schroeder & Craig, Citation2021). However, within dialogue-based computer-assisted language learning (DB-CALL), earlier research has mostly focused on measuring the effects on higher education students’ language learning when using SDSs (Bibauw et al., Citation2019, Citation2022). Comparatively, little attention has been paid to how students experience interacting with ECAs to practice speaking skills in a target language and the social elements of these agents.

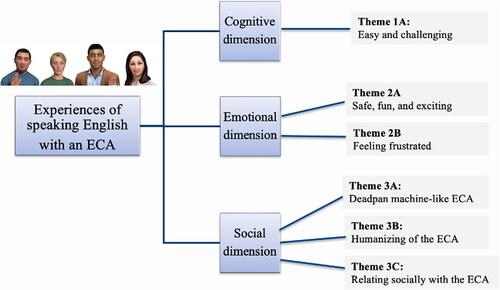

The aim of this study was to expand the understanding of how middle school students experience the use of conversational AI for spoken interaction. It explored students’ self-reported experiences when engaging in simulated spoken conversations with human-like ECA as interlocutors providing instant feedback in spontaneous dialogues in the target language in an AI-based SDS (Enskill; Alelo, Citation2022; Johnson, Citation2019). We applied dimensionalizing as a method to measure and analyze complex concepts for refined understanding (De Vaus, Citation2001), here of the students’ experiences of speaking with ECAs in cognitive, emotional, and social dimensions. The study at hand explores a novel interactive context, whereof the findings and analytical methods intended to expand on the knowledge base for handling speaking at the primary education level. Potentially, it also provides knowledge about the various student reactions that this kind of speaking activity entails. As such, our research question asks: What characterizes middle school students’ experiences when practicing speaking with ECAs in a foreign language learning context?

Related research

Foreign language speaking skills

We define speaking in this study through the work of the following authors. Speaking is a demanding, dynamic, and complex “combinatorial skill” (Johnson, Citation1996, p. 155), referring to various interplaying processes (cognitive, affective, and social) that are engaged simultaneously in speech production for fluency, accuracy, and complexity. For example, the ability to combine different linguistic elements (e.g. words and phrases) correctly in real-time is learned through extensive practice. Speaking is suggested to include the core speaking skills: pronunciation, own production of utterances and making oneself understood, and an ability to keep a conversation flowing adequately in the social context (Goh & Burns, Citation2012). When engaging in spoken conversation, there is also a receptive aspect involved, listening comprehension skills (Hodges et al., Citation2012). Recognized emotional factors (Swain, Citation2013) and varying levels of anxiety, motivation, and self-confidence regarding speaking in the target language affect students’ involvement in speaking and their willingness to speak (Goh & Burns, Citation2012). As such, speaking skills are influenced by social interaction between interlocutors.

Developing speaking skills depends on student interaction in social contexts (Loewen & Sato, Citation2018). In line with Vygotsky’s (Citation1978) idea of the Zone of proximal development, the potential to develop higher-level speaking skills in a foreign language is enhanced when the student is speaking with someone who is more capable (an expert). Supporting this concept, Gibbons (Citation2015) suggested that the student must be suitably cognitively challenged in relation to the degree of support for engagement. However, to develop those skills, the students must use their target language actively in task-based activities, where they interact orally to complete the task in everyday-life scenarios (Ellis, Citation2003). As summarized by Li (Citation2017), some established key principles that can contribute to developing speaking are an opportunity for interaction, authentic input, in-time and individualized feedback, and a low affective filter.

Developing foreign language speaking skills with ECAs in an SDS

Studies have shown that spoken interaction in simulated everyday-life scenarios with ECAs promotes speaking skills (e.g. Bibauw et al., Citation2022; Johnson, Citation2019; Wang et al., Citation2022). These agents facilitate an opportunity for exposure to a conversation in the target language (Divekar et al., Citation2021) through the students and ECAs taking turns (Huang et al., Citation2022). The students “are expected to input, feedback, and interact in a way similar to what they would experience in face-to-face interaction” (Li, Citation2017, p. 53). The complexity of interactions and how they are carried out are affected by the predetermined constraints of the SDS that balance the system’s conversational freedom (McTear, Citation2020). It is a safe low-anxiety environment (Golonka et al., Citation2014) where oral interaction can be constructed at any time, providing instant feedback and individual assessment (Bibauw et al., Citation2019; Timpe-Laughlin et al., Citation2022). The use of agents in language learning can help students feel less nervous about speaking in a foreign language and keep them motivated (Fryer et al., Citation2019). Ayedoun (et al., 2019) have revealed that practicing in an SDS has an impact on learners’ willingness to communicate, with a rise in confidence and lower anxiety levels. These benefits to spoken language learning through the use of conversational AI are relevant for application in foreign language education contexts and provide reasoning for its investigation here.

Although few SDSs with ECAs that have been investigated have moved beyond initial prototypes (Bibauw et al., Citation2019), the initial findings have been promising. SPELL, a three-dimensional virtual world in regard to which university studies have reported high user engagement and also feeling more relaxed speaking with ECAs than with their peers (Anderson et al., Citation2008). In line with these findings, Johnson (Citation2019) has shown promising results in higher education when introducing the SDS Enskill (Alelo, Citation2022). Fluency and accuracy measured with system-generated metrics showed, for instance, an increased number of conversational turns per minute. The students’ attitudes showed gained self-confidence and enjoyment of practicing speaking in the system, still with mixed voices around technical issues and constraints.

Bibauw et al. (Citation2022), in their meta-analysis, found no significant change in speaking skills development in relation to the physical embodiment of conversational agents compared with speech-only interfaces. However, the related fields of ECAs, pedagogical agents and virtual humans (Burden & Savin-Baden, Citation2019; Davis et al., Citation2021) have explored embodiment features and social cues in a manner that might be vital for the experience and learning (e.g. Craig & Schroeder, Citation2018), supposedly also for language learning and will therefore be presented briefly next.

Social interaction

Craig and Schroeder (Citation2018) have shown evidence for the impact on learning that students’ believed sense of social connection with system-controlled virtual humans has had. The researchers’ suggested design principles include virtual humans as interface elements, such as human voice, temporal contiguity considerations with speech and gestures for virtual humans as social facilitators. Using social cues such as facial expression, conversational gestures, speech, and movement to emulate human-like characteristics and behaviors (Burden & Savin-Baden, Citation2019), virtual humans can create socially immersive experiences, providing social connections similar to those that typically occur in human-to-human interaction (Divekar et al., Citation2021). This is achieved through, for instance, displaying emotions, providing feedback, and acting in a seemingly empathetic way (Craig & Schroeder, Citation2018). Lawson et al. (Citation2021) have found that pedagogical agents’ displaying positive emotions (e.g. happy) affected students’ lesson understanding positively. Socially attractive agents have more potential to be adopted as communicational partners (Davis et al., Citation2021).

Additionally, according to the social agency theory, humans interacting with computers through agents tend to ascribe human attributes to them, with the result that humans sometimes treat agents like actual humans and have human-like expectations of them, a phenomenon also known as humanizing or anthropomorphizing (Reeves & Nass, Citation1996), which might add to the sense of social interaction (Bickmore & Cassell, Citation2005).

Schroeder et al. (Citation2013) have highlighted learning success attributed to “a feeling of social interaction between the learner and the agent” (p. 20). Such interactive aspects have also recently been recognized in the context of language learning, where young students’ affection for the appearance of the humanlike ECAs positively predicted enjoyment and, in turn, also learning gains (Wang et al., Citation2022). Other studies yield evidence that users’ self-efficacy to speak and develop their foreign language increases when using a system with socially intelligent ECAs giving feedback (Wang & Johnson, Citation2008), a high social presence, high levels of human-likeness (Ebadi & Amini, Citation2022) and emotional expressiveness (Ayedoun & Tokumaru, Citation2022). Therefore, gaining insights into the students’ diverse experiences of speaking with ECAs is central to expanding our understanding of the underlying aspects of student-to-ECA interactions that make them meaningful and potentially effective for language learning.

Methods and materials

We let 22 students in a convenience sample of 13-year-old students studying English as a foreign language in a middle school (seventh grade) in Sweden practice speaking in an SDS. Background information (gained through a pretrial questionnaire) about the students revealed that they were all daily users of digital devices and that half of the students had previous experience speaking with some kind of agent. A majority was positive about speaking English and found it easy and fun. However, almost half (N = 10) of the students felt anxious or nervous about speaking English during lessons, whereof five coincided with being positively rating about speaking.

This study drew on students’ self-reported experiences for both its design and its analysis. We applied the term ‘experience’ in close connection with learning and development, integrating intellectual, affective, and social dimensions (Roth & Jornet, Citation2014). Given the novelty from the perspective of a student of the kind of educational speaking activity studied, which provides completely new forms of interaction and experiences for students, there was, to our knowledge, currently no suitable framework for studying self-reported experiences of student–ECA interaction in an SDS. Hence, the analytical framework applied was designed with inspiration from two frameworks used to study human-to-human online learning in higher education, namely, collaborative learning (Garrison et al., Citation1999) and one-to-one learning, respectively (Stenbom et al., Citation2016). The former framework has recently been explored in a study on AI presences (Wang et al., Citation2022).

In our study, to operationalize students’ diverse and complex self-reported experiences of speaking with an ECA, we delineated the speaking experience into three interrelated dimensions (cognitive, emotional, and social) to refine our understanding. The cognitive dimension focused on intellectual ability, that is, how students experience speaking with ECAs. The emotional dimension focused on personal emotions in relation to speaking with an ECA, the outcome emotion (e.g. satisfied), and emotions toward an ECA. The social dimension focused on the establishment of social relationship with ECAs, the extent to which students felt comfortable (natural) speaking with ECAs, and how they humanized the ECA during a conversation.

Considering threats to construct validity (Shadish et al., Citation2002), the selection of concepts used in the study was informed by earlier research. Speaking skills were defined in line with Goh and Burns (Citation2012) and were together with the established key principles (Li, Citation2017) applied in instruments in relation to the experience of speaking.

For the moment, at least, human-to-ECA interactions lack the mutually shared experiences that characterize human-to-human interactions. Due to this limitation, this study explored students’ self-reports of their cognitive, emotional, and social experiences, although—it should be noted—some scholars claim self-reports to be unreliable (e.g. Dunlosky & Metcalfe, Citation2008) because of various biases. Immediate and regular meta-reflection of emotions in a logbook is a way of eliminating any retrospective unreliability of emotional self-judgment, as described by Mills and D’Mello (Citation2014). However, with this method, there is a risk that incidental emotions are recorded along with non-incidental emotions.

Setup of speaking sessions in Enskill

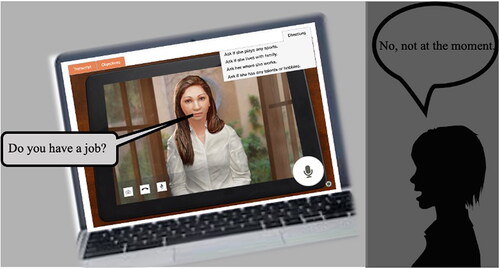

The speaking activity took place in the SDS, Enskill, in which the students while sitting in a classroom, interacted individually with one ECA at a time. The students used their laptops and were provided with headphones, including a microphone. The ECAs in this system were visually represented as human-like male or female adult characters. During the conversations, in sync with the speech, the ECAs emulated body language, conversational gestures (without conveying information), and direct eye contact. They were designed to respond to students’ input and interact like humans while being the communicational counterpart of the student, as shown in and in the following excerpt from a spoken conversation (interview) between the ECA Lily, initiating the dialogue with the student (S):

These ECAs were part of the SDS, a cloud-based platform on the cognitive services Microsoft Azure and LUIS, with data-driven development applying advanced natural language processing (Johnson, Citation2019). The students used spontaneous speech and alternative utterances that were supposed to be recognized by the system if they were within the context of the selected scenario. The ECA acted as an expert speaker and assistant. We interpret this as a relation similar to a novice-expert in terms of allowing for learning in interaction (Vygotsky, Citation1978). The ECA directed the conversation in terms of taking turns, sometimes asking the student to repeat the previous utterance, thus giving instant feedback on the student’s output (including meaning and form). The ECAs guided and instructed students in the system and also provided text-based instruction and optional displayed suggestions of utterances (direction) and objectives (see ).

Figure 1. A female ECA in Enskill (Citation2022) interacting with a student in English.

Note. Screenshot of a conversational scenario in Enskill. ©Alelo Inc. Use with permission.

The students were introduced to the ECAs through the system’s instructional video and were encouraged to act autonomously. The teacher acted as a facilitator for setting up the use of the system, and selected scenarios, integrated theme-wise as part of ordinary English classes. The included variety of ECAs was pre-selected by the system for each scenario. The levels of the scenarios were basic, corresponding to the students’ approximate beginner and elementary proficiency levels (A1 & A2, Council of Europe, Citation2020). The system was originally designed to target higher education students. Each student was supposed to maintain face-to-face dialogues in English, dealing with what is intended to be everyday-life situations, by asking questions, answering questions, and solving a practical task, such as ordering at a restaurant or interviewing someone (see excerpt of transcript). Hence, the pedagogical framework of the system was task-oriented (Ellis, Citation2003) and in line with the European communicative approach (Council of Europe, Citation2020).

The students engaged in two speaking sessions one week apart from each other. They were instructed to practice speaking in the system for 15 min per speaking session, instantly followed by five minutes of written reflection in their logbook (LoopMe, Citation2021). Ethical factors were considered, and base principles were respected (Swedish Research Council, Citation2017) in line with GDPR (Citation2018) and internet research principles (Franzke et al., Citation2019). Informed consent was obtained pretrial from the students and their caregivers.

Data production

The analyzed dataset consists of data from two sources: (i) a digital logbook and (ii) a post-task questionnaire. Such a multi-method approach (Bergman, Citation2008; Creswell & Creswell, Citation2018) allows for unpacking the students’ activities (Levy, Citation2015), considered particularly relevant for our exploration of the students’ experiences and analysis of what might influence these experiences. We constructed the logbook and the questionnaires in Swedish and let the students mainly answer in Swedish. The formulations used were adapted to the age group and tested in a pretrial pilot on the same age group.

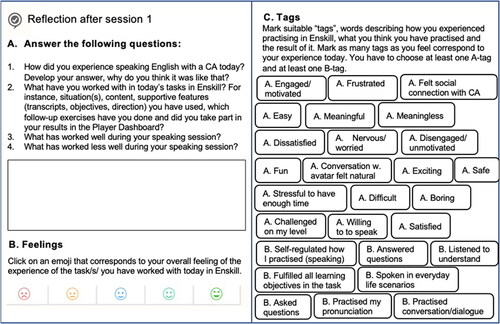

To collect immediate subjective experience after each of the two speaking sessions, the students wrote in a digital logbook, LoopMe, based on a development of Experience Sampling (Hektner et al., Citation2007; Lackéus, Citation2020). As illustrated in , the students first answered four open-ended questions about the speaking session. Second, they rated their overall experience with an eligible emoji on a five-graded Likert scale. Third, the students selected from among 27 representative tags prepared for this study, which corresponded to A) experiences of the speaking practice (e.g. “fun,” “safe,” and “frustrated”) and B) what they thought they had practiced and the result of it (e.g. “practiced conversation/dialogue”). There was no given maximum number of tags to select.

Figure 2. Reflection post in the digital logbook LoopMe (Citation2021).

Note. Translated from Swedish into English. CA was used as an acronym for the conversational agent in communication with the students.

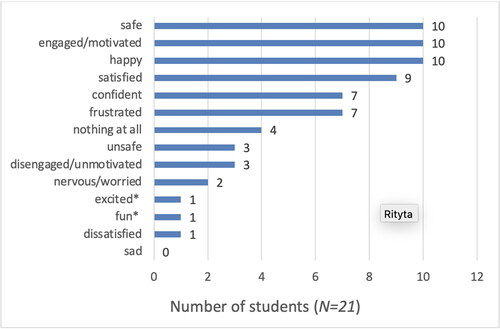

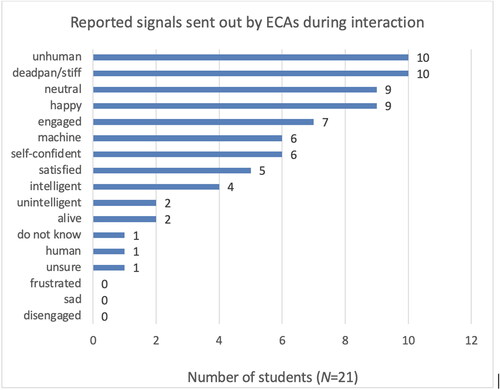

After the two sessions, the students answered a post-task questionnaire about experiences of speaking with ECAs, drawing on a questionnaire for one-to-one online learning (Stenbom et al., Citation2016) adapted to this educational context and relevant for exploring our three dimensions of experience (cognitive, emotional, and social). Items measuring user experience of conversational interfaces (here ECAs) were redesigned based on Kocaballi et al. (Citation2018) to give a nuanced understanding of the students’ speaking experience. It took approximately ten minutes to answer the 23 questions (18 ratings, 3 multiple-choice, 2 open-ended items, plus one possibility to add extra). We used a five-point Likert scale in ratings (e.g. 1 = not at all, to 5 = to a great extent) or options that were mutually exclusive (e.g. 1 = very hard, to 5 = very easy). Questions about the cognitive dimension were about how students experienced speaking with ECAs, making themselves understood by the and understanding the agents, maintaining the flow of conversation, and, finally, whether they had been individually challenged by the activity. Emotionally related questions focused on to what extent the students reacted emotionally in the conversations, how they valued speaking with ECAs as “fun,” “safe,” “exciting,” “meaningful,” but how, on the other hand, they “felt stressed when trying to keep up with the tempo of the conversations.” Concerning students’ feelings during conversation, they chose among eligible word (one or many; as presented in the Result section, see ). Questions about the social dimension concerned whether they felt comfortable/natural speaking with an ECA or connecting with them socially, how they found collaborating with ECAs to solve tasks, and to what extent they found speaking with ECAs to be like a human-to-human interaction. Also, they chose among eligible words how they experienced the ECA (one of many; as presented in the Result section, see ). All dimensions together were explored by means of the students’ ratings of “overall experience,” consisting of their interpretation of the three aggregated dimensions in the item: “How, overall, do you experience speaking English with a CA” (1 = very bad, to 5 = very good).

Data analysis

First, quantitative data produced in logbooks and post-task questionnaires (N = 21) were analyzed through descriptive statistics. A codebook was created (as suggested by Pallant, Citation2011) with items from the post-task questionnaire given variable names related to the predefined dimensions to which they connected (cognitive, emotional, and social), plus one item measuring the overall speaking experience. After the first (N = 21) and second (N = 22) sessions, aggregated data from a total of 43 logbook entries were exported into SPSS for analysis. The students’ selection of tags was understood to represent what they experienced as the most prominent experiences. Tags were balanced detachedly per session (original number of used tags divided by the total number of logbook entries per session) and overall (sum of all used tags divided by the total number of logbook entries). Likert scale data (emojis) were drawn from a 5-point rating scale ranging from −2 to 2, with negative numbers representing overall negative emotional states and positive numbers representing overall positive states, respectively. An individual mean emoji rating was calculated.

However, as our goal was to unpack students’ experiences of the interaction, the main part of the analysis drew on qualitative analysis of the post-task questionnaire comments in an open format and written reflections from logbook data. To identify and analyze themes, the qualitative dataset was read through and interpreted using a data-driven (bottom-up) approach (as described by Braun & Clarke, Citation2019) and was further reviewed and refined repeatedly through reflexive thematic analysis. These were then organized into three dimensions. A collegial review was performed throughout the analysis process, including discussions for inter-rater coding reliability between the two coders in a few cases of discrepancies. To report the study results, the first author translated student quotes, tags, and ratings from Swedish into English.

Results

Six analytical themes were developed. These are organized under the three dimensions and are consequently presented as such in this section, as visualized in . Quantitative ratings and choices (from logbooks and post-task questionnaires) are presented initially within suitable dimensions. Additionally, all dimensions were synthesized into students’ self-reported summarized (overall) experience of speaking English with an ECA (one questionnaire item and selected tags).

Cognitive dimension

The students reported finding it easy or very easy to speak with (57%) and listen to and understand” (81%) the ECA. Half of the students thought that it worked well or very well in relation to making themselves understood (48%), as demonstrated by the students’ frequent total use of the tag easy in the logbook entries (49%). Most of the students rated average on maintaining the flow of conversation with the ECA, whereas just a third rated it as good or very good. Thirty-eight percent of the students reported experiencing the selected conversation simulation as challenging to master in relation to their own level of speaking proficiency.

Easy and challenging (Theme 1A)

The students were able to separate intended and unintended challenges in the activity. While reporting on the system as relatively easy to use, they still experienced challenges in succeeding in the given tasks. They also reported on their ability to understand why the system put them in challenging situations. For example, “It feels somewhat challenging, but that’s good because I learn new words and how/in what ways you can ask questions, for example” (Student 9). Providing they found it optimally challenging, the students reported the development of their speaking skills through the active use of the foreign language. “I managed this time to start a conversation that flowed, the avatars understood what I said, and I did not have to repeat myself at all” (Student 12). Evidently, there were individual differences, as shown in the following excerpt: “Sometimes the questions are somewhat too easy; the conversations are not so challenging. However, although it does not challenge me, the project is exciting and fun to try” (Student 5).

Emotional dimension

Most of the students (62%) reported the speaking activity as meaningful with respect to the development of speaking skills. Just 12% (N = 3) of students reported it as being not meaningful at all. Most of the students rated the entire speaking activity in the system as being safe (90%) in comparison with traditional educational settings and speaking to human beings. The students generally reported that they found it fun (86%; also the most frequently used tag, as shown in ), exciting (81%), and not stressful because of the pace of exercises (90%).

Table 1. Student tags and rated emojis per session in the logbook LoopMe (Citation2021) .

A slight majority (N = 11) reported emotional reactions, whereas 10 students reported no or low emotional reactions during conversations. The words selected by students in the questionnaire to illustrate their feelings (see ) involved during the speaking activity showed somewhat more positive than negative emotional engagement, with happy (48%) and engaged/motivated (48%) being reported, more than feeling frustrated (33%) (also used in 30% of the tags). Frustration was often linked to technical issues, such as constraints in the system (see further in the section headed (de)Humanizing of the ECA). Additionally, some students reported having mixed feelings during conversations with ECAs, as shown by the feelings selected by two different students: engaged/motivated, nervous/anxious, and safe, and engaged/motivated, satisfied, frustrated, confident, and unsafe. The outcome emotion after a conversation with the ECA was satisfaction to a great or very great extent for slightly more than half of the sample (52%).

Safe, fun, and exciting (Theme 2A)

Students reported experiencing low anxiety and even feeling more confident speaking with the ECA than compared to a fellow student: “I dare to speak more than I do with a person in my class” (Student 15). The feeling of not being judged by the ECA, but rather supported, is also brought up in terms of safety: “It feels safe, since it will not assess how you pronounce, and it will not be mean but only give you a piece of advice how you can improve or what you have been good at. It also feels exciting because it is not a real person” (Student 21); or as summarized here: “It is pretty fun and exciting; it is safe too since an avatar does not care if you make mistakes or so. It does not feel stressful at all; the tempo is good” (Student 9). The same student added: “I speak much better English when I am with someone I feel safe with.” Individual differences that occur concern expressed emotions: “I do not think that it is very challenging, it is not fun, and I feel safe when I “speak” with it, if it understands what I am saying. I understand the idea, but I do not like it” (Student 8).

Feeling frustrated (Theme 2B)

The following quote gives insight into what would be required for the student’s frustration to be reduced in the interaction: “that the avatar [ECA] answers the question, even if it is reformulated. And that you should be able to answer the way you want, and not the way the avatar wants. I understand that it might be hard to make this possible, but then you would be much less frustrated” (Student 5). The problem that the ECAs did not hear or understand the students properly was commented upon frequently in relation to frustration: “It said ‘I don’t understand you’ all the time, and this is my biggest issue with this exercise” (Student 13). Some students also reported that their experiences were transformed as they got more used to the process, as expressed here: “I was somewhat frustrated, but then it became fun’ (Student 4)”.

Social dimension

More than a third (38%) of the students reported no or little social connection between themselves and the ECA. A majority (62%) reported a social connection with the ECA, recognizing human characteristics. The students reported the ECAs as happy (43%) and engaged (33%), which contrasted with other signals such as unhuman (48%) and deadpan/stiff (48%), as visualized in . The ECAs were also reported as having neutral characteristics (43%) during conversations. We noticed that no student chose the eligible alternatives disengaged, frustrated, or sad as representing the characteristics of the ECAs during the conversation. The majority reported feeling comfortable in the conversation (76%) and collaborating with the agents to solve tasks (62%). Almost half of the students experienced their interaction with the ECA as being comparable to speaking with a human being in a similar situation (48%) and were equally or more comfortable and natural online in comparison to human-to-human conversation in the classroom (67%).

Deadpan machine ECAs (Theme 3A)

Students referred to the ECA as deadpan, machine-like, and non-human in the interaction while mentioning the interlocutor as “it” or “the avatar” without using personal names or pronouns. These students experienced their interaction with the ECA as unnatural and as human–machine interaction: “Because I speak with a computer and not a human being” (Student 23) and “the avatar looks almost dead and mannered” (Student 21). Although these students experienced feelings of safety and satisfaction, they found themselves feeling unengaged/unmotivated, and frustrated.

(de)Humanizing of the ECA (Theme 3B)

The use by students of humanizing words about ECA’s actions (or expected actions) indicates that they see the agents as having human capacity. The use of personal pronouns and a sense of the ECAs as having a will of their own in descriptions of them indicate that the ECAs are experienced as counterparts: “It did not want to say their [“hen” in Swedish] name (Student 16) and “she did not want to understand what I wanted to say” (Student 5). The ECAs’ limited ability to express themselves and understand the students was often criticized: “Irl [in real life], you can say anything, but with the avatar, it is limited what you can say” (Student 22). The conversation was reported as constrained, and ECAs were seen as not being as sensitive to linguistic mistakes as humans. Some students reported similarities to speak with a human, whether in real life or online: “You speak about the same things, but you see that it is not a real human being” (Student 15). Other students reported limitations:

If you do not say exactly what the avatar [ECA] wants, you will not receive any answer. So, when I try to formulate the question differently, it does not understand, whereas when I say exactly what it wants, it answers. It is somewhat unnatural how it decides what you should answer. Real people do not do this; I understand, however, that it can be hard to program many different answers, but it is somewhat unnatural. (Student 5)

Relating socially to the ECA (Theme 3C)

Some students not only humanized the ECA but also reported relating (or at least attempting to relate) socially to the ECA: “It is like speaking with someone online” (Student 20). “I spoke with Lily [an ECA], and we interviewed each other” (Student 11). One student tried to finish the session in a personal way: “I was not allowed to say ‘Goodbye’ at the end” (Student 11). The word “conversation” signals social relating and interchange between a student and the agent, although it is less natural: “When you speak with a real human, the conversation is often more relaxed, whereas the conversation is not as natural with the avatar [ECA]” (Student 12).

Students’ ratings and tags of the overall experience of speaking with an ECA

The majority reported positive (average to very good) overall experiences of speaking with ECAs (81%). Overall, the experience was most frequently rated using the 1 (good) emoji (60%): “It was fun but somewhat nerve-racking” (Student 16). The overall experience of the students had a median emoji value of one and a mean value of 0.6 (range −2 to 2), with discrepancies between individual values. As shown in , among all tags used, the students tagged the overall experience most frequently as fun (56%) and easy (49%). The students referred to in Theme 3 A, who experienced social distance between themselves and the ECA, reported more negative experiences. In cases with the lowest reported emoji ratings (-2 and −1), common explanations related to the ECA’s inability to understand them: “It was fun but frustrating” (Student 2). Other students made suggestions as to how to make the activity more challenging: “I think that it would maybe have been somewhat more fun and exciting if more unexpected things happened in the conversation” (Student 14).

The tempo was experienced as slow, and the interaction less rich, which for some was a drawback, while it was appreciated by others since it allowed thinking before speaking. After the first session, diversity in rated emojis was maximal (-2 to 2), whereas, after the second session, the majority raised their ratings. There were indications that they felt safer, braver, and more satisfied with more speaking practice with the ECAs. Reported frustration decreased (48% to 14% of the used tags). The majority of the students raised the ratings of their overall experiences after session two. Over time, the students gradually began to feel safer and enjoyed speaking with the ECAs.

Discussion

The reflexive thematic analysis yielded six themes within the three dimensions of operationalizing experiences, presented in combination with the descriptive statistics in line with the dimensions and themes. The key results indicate that the students found it easy to speak with, listen to, and understand the ECAs. As shown in the section on the cognitive dimension of experience, in line with Bibauw et al. (Citation2022), the students experienced instant feedback from the ECA on input in the interaction since they reported being able to keep the conversation flowing. Some found themselves pushed forward and optimally challenged (Gibbons, Citation2015) while interacting with a more capable speaker of the target language (Vygotsky, Citation1978). These results are in line with earlier research indicating that technology that uses natural language processing can enhance the development of speaking and listening skills (Divekar et al., Citation2021; Golonka et al., Citation2014; Johnson, Citation2019).

Emotionally, most of the students found the speaking activity fun (Johnson, Citation2019), exciting, meaningful, and less anxious -findings in line with Ayedoun et al. (Citation2019) and did not find keeping up with the tempo stressful. We noticed that almost half the sample reported no or low emotional reactions (inner or outer). Still, almost half of the sample reported feeling happy and engaged when interacting with the ECA, representing emotions that play an important role in language learning (Swain, Citation2013). The majority felt safe, and some students found themselves feeling even safer than in a human-to-human conversation, in line with earlier research (Anderson et al., Citation2008). However, some students initially reported feeling embarrassed when surrounded by classmates simultaneously engaged in the same speaking activity. The relationship between feelings within the interaction and the interaction being part of an educational activity in a classroom is interesting and regarded as a matter for consideration in future work. Students reported being were frustrated over ECAs’ limited range of speaking and interacting (Johnson, Citation2019) including inability to deal with disturbance in turn-taking.

Regarding the social dimension of experience with the ECAs, there was a whole spectrum reported, including students seeing the agent as a deadpan machine, others describing the ECA in human terms, ascribing human attributes, feelings, and behaviors (Ebadi & Amini, Citation2022; Lawson et al., Citation2021). Finally, students reported socially relating to and collaborating with ECAs (Craig & Schroeder, Citation2018; Walker & Ogan, Citation2016) and, indeed, in some cases, seemingly striving to do so. Relating socially to ECAs is the theme with the widest range of individual variation, which can have implications when introducing these humanlike agents for interaction as an educational activity. Interaction with ECAs seems less engaging and effective for those students who do not socially relate to them. However, during the actual interaction and between different sessions, some students moved between different experiences, which is interesting and somewhat complicates how social relating, authenticity, and immersion in these interactions can be understood. Possible explanations can be the students’ emotions (Swain, Citation2013) toward the selected task to solve or the individual sensibility for technical issues or constraints in the system. The experiences of the students striving for humanizing and social relating described in their comments echoed Craig and Schroeder (Citation2018) suggested design principles for virtual humans as social facilitators (e.g. outward appearance and feedback). In line with (Ayedoun & Tokumaru, Citation2022), students experienced emotionally expressive ECAs (e.g. happy and engaged). The constraints around the ECA’s speaking abilities (c.f., Johnson, Citation2019; Wang et al., Citation2022) seemed to affect the social experience negatively, and the students commented extensively on these constraints. The students wished to have more spontaneous conversations with fewer constraints in the SDS, more like a human-to-human conversation (Davis et al., Citation2021). This result is in line with a systematic review of SDSs:

To design a dialogue-based CALL application is to find an adequate balance between constraints, which guide and focus the user production, to reduce its unpredictability and allow its automated processing, and freedom left to the learner to express their own meanings interactively. (Bibauw et al., Citation2019, p. 31)

Limitations and future work

We note that the results are valid for this modest sample size of digitally experienced middle school students’ experiences of speaking with ECAs in this SDS (originally not designed with this age group in mind). There would be low statistical power of the quantitative data on their own, therefore used in combination with the qualitative data for a deeper understanding of the students’ experiences. Applying dimensionalizing of experiences in combination with the suggested instruments can be up-scaled and conducted in other age groups, as well as longitudinally. We suggest further exploration of the impact of socializing with ECAs on students’ foreign language learning outcomes (quantitative measures) and educational experience in an SDS over time.

Conclusion

This paper has added to Schroeder and Craig (Citation2021) call to understand how students and agents interact for learning, here applied ECAs for practicing foreign language speaking skills in spoken interaction (Bibauw et al., Citation2019). Based on self-reports, the results demonstrated cognitively satisfied and emotionally and socially engaged middle school students speaking with ECAs, with experiences that aligned with established key principles promoting the development of speaking skills (Goh & Burns, Citation2012; Li, Citation2017; Swain, Citation2013) in social interaction (Loewen & Sato, Citation2018). Within all dimensions of experiences, there were individual differences, but most prominently within the social dimension, where many of these students humanized and even connected socially with the ECAs. These results align with earlier research on design principles for learning and engagement in AI-based systems (Craig & Schroeder, Citation2018; Walker & Ogan, Citation2016). Hence, this paper’s results resonate with earlier findings that student-to-ECA interaction allows efficient practice of foreign language speaking skills (e.g. Huang et al., Citation2022; Bibauw et al., Citation2022; Johnson, Citation2019), expanding evidence also for this younger age group of students. For some of them, the use of ECAs in this kind of system is less beneficial, as they do not relate socially with the agents but rather experience them as a non-humanlike deadpan machine. The speaking activity nevertheless seems to be experienced as satisfying and safe, but with frustration linked to the constraints of the ECAs’ speech abilities and the system, generally reported as playing a major role in shaping these students’ experiences.

Acknowledgments

Our study has been made possible thanks to Alelo, so major acknowledgment is due to Ph.D. Lewis Johnson, President, and CEO. Many thanks, not least to the participating students and their teacher.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Elin Ericsson

Elin Ericsson is a Ph.D. student at the University of Gothenburg in the Department of Applied IT, working in the division for Learning, Communication, and IT. She is part of two research schools: The Center for Education Science and Teacher Research and GRADE, a national graduate school that focuses on digital technologies in education. Her research project is within the field of dialogue-based computer-assisted language learning (DB-CALL) and concerns the use of spoken dialogue systems and how they can enhance and complement the teaching and learning of foreign languages, especially with regard to speaking skills.

Johan Lundin

Johan Lundin is a professor of informatics in the Department of Applied IT at the University of Gothenburg. Johan is interested in how information technology changes the conditions and possibilities for learning and knowing. He explores technology in action, conducting empirical and design-oriented studies concerned with the analysis of how IT features in social action and interaction. He researches the use of IT in educational practices and IT support for competence management at workplaces and conducts design-oriented research developing IT for learning and education.

Sylvana Sofkova Hashemi

Sylvana Sofkova Hashemi is a senior lecturer in the Department of Education, Communication, and Learning at the University of Gothenburg. The aim of her research is to advance understanding of the changed text and media landscape in a synergy between language, technology, and learning. Sylvana’s research is devoted to investigating language use and how students develop the textual and multimodal competencies that, as future citizens, they need to acquire. Using practice-oriented approaches, her research pays attention to the analysis and development of technology-mediated teaching to support the development of technology in relation to content, pedagogy, and other frames that influence design for learning.

References

- Alelo. (2022). Enskill English® Revolutionize English language teaching with AI. Alelo Inc. Retrieved April, 2023, from https://www.alelo.com/english-language-teaching/

- Anderson, J. N., Davidson, N., Morton, H., & Jack, M. A. (2008). Language learning with interactive virtual agent scenarios and speech recognition: Lessons learned. Computer Animation and Virtual Worlds, 19(5), 605–619. https://doi.org/10.1002/cav.265

- Ayedoun, E., Hayashi, Y., & Seta, K. (2019). Adding communicative and affective strategies to an embodied conversational agent to enhance second language learners’ willingness to communicate. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 29(1), 29–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-018-0171-6

- Ayedoun, E., & Tokumaru, M. (2022). Towards emotionally expressive virtual human agents to foster L2 production: Insights from a preliminary Woz experiment. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, 6(9), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti6090077

- Bergman, M. M. (2008). The straw men of the qualitative-quantitative divide and their influence on mixed methods research. In M. M. Bergman (Ed.), Advances in mixed methods research theories and applications (pp. 11–23). SAGE.

- Bibauw, S., François, T., & Desmet, P. (2019). Discussing with a computer to practice a foreign language: Research synthesis and conceptual framework of dialogue-based CALL. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 32(8), 827–877. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2018.1535508

- Bibauw, S., François, T., Van den Noortgate, W., & Desmet, P. (2022). Dialogue systems for language learning: A meta-analysis. Language Learning & Technology, 26(1), 1–24. https://hdl.handle.net/10125/73488

- Bickmore, T., & Cassell, J. (2005). Social dialogue with embodied conversational agents. In J. C. J. van Kuppevelt, L. Dybkjær, & N. O. Bernsen (Eds.), Advances in natural multimodal dialogue systems. Text, speech and language technology (Vol. 30, pp. 2–32). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-3933-6_2

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, & K. J. Sher (Eds.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol. 2: Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological (pp. 57–71). American Psychological Association.

- Burden, D., & Savin-Baden, M. (2019). Virtual humans today and tomorrow. CRC Press.

- Council of Europe. (2020). Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment – Companion volume. Council of Europe Publishing. Retrieved from www.coe.int/lang-cefr.

- Craig, S. D., & Schroeder, N. L. (2018). Design principles for virtual humans in educational technology environments. In K. Millis, D. Long, J. Magliano, & K. Wiemer (Eds.), Deep learning: Multi-disciplinary approaches (pp. 128–139). Routledge/Taylor Francis.

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage Publications, Inc.

- Davis, R. O., Park, T., & Vincent, J. (2021). A systematic narrative review of agent persona on learning outcomes and design variables to enhance personification. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 53(1), 89–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2020.1830894

- De Vaus, D. (2001). Research design in social research. SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Divekar, R., Lepp, H., Chopade, P., Albin, A., Brenner, D., & Ramanarayanan, V. (2021). Conversational agents in language education: Where they fit and their research challenges. Communications in Computer and Information Science, 1499, 272–279.

- Dunlosky, J., & Metcalfe, J. (2008). Metacognition. SAGE Publications.

- Ebadi, S., & Amini, A. (2022). Examining the roles of social presence and human-likeness on Iranian EFL learners’ motivation using artificial intelligence technology: A case of CSIEC chatbot. Interactive Learning Environments, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2022.2096638

- Ellis, R. (2003). Task-based language learning and teaching. Oxford University Press.

- Franzke, A., Bechmann, S., Zimmer, M., Ess, C. (2019). Internet research: Ethical guidelines 3.0: Association of internet researchers. https://aoir.org/reports/ethics3.pdf.

- Fryer, L. K., Nakao, K., & Thompson, A. (2019). Chatbot learning partners: Connecting learning experiences, interest and competence. Computers in Human Behavior, 93, 279–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.12.023

- Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (1999). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2–3), 87–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00016-6

- GDPR. (2018). General data protection regulation. Retrieved October 2022, from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/oj

- Gibbons, P. (2015). Teaching English language learners in the mainstream classroom. Heinemann.

- Goh, C. C. M., & Burns, A. (2012). Teaching speaking: A holistic approach. Cambridge University Press.

- Golonka, E. M., Bowles, A. R., Frank, V. M., Richardson, D. L., & Freynik, S. (2014). Technologies for foreign language learning: A review of technology types and their effectiveness. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 27(1), 70–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2012.700315

- Hektner, J. M., Schmidt, J. A., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2007). Experience sampling method -Measuring the quality of everyday life. Sage Publishing.

- Hodges, H., Steffensen, S. V., & Martin, J. E. (2012). Caring, conversing, and realizing values: New directions in language studies. Language Sciences, 34(5), 499–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langsci.2012.03.006

- Huang, W., Foon Hew, K., & Fryer, L. K. (2022). Chatbots for language learning—Are they really useful? A systematic review of chatbot-supported language learning. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 38(1), 237–257. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.1261

- Johnson, K. (1996). Language teaching and skill learning. Bert.

- Johnson, W. L. (2019). Data-driven development and evaluation of enskill English. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 29(3), 425–457. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-019-00182-2

- Kocaballi, A. B., Laranjo, L., & Coiera, E. (2018). Measuring user experience in conversational interfaces: A comparison of six questionnaires [Paper presentation]. Proceedings of the 32nd International BCS Human Computer Interaction Conference HC 2018, BCS Learning and Development Ltd. https://doi.org/10.14236/ewic/HCI2018.21

- Lackéus, M. (2020). Collecting digital research data through social media platforms: Can ‘scientific social media’ disrupt entrepreneurship research methods? In W. B. Gartner & B. Teague (Eds.), Research handbook of entrepreneurial behavior, practice, and process Cheltenham. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Lawson, A. P., Mayer, R. E., Adamo-Villani, N., Benes, B., Lei, X., & Cheng, J. (2021). Do learners recognize and relate to the emotions displayed by virtual instructors? International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 31(1), 134–153. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-021-00238-2

- Levy, M. (2015). The role of qualitative approaches to research in CALL contexts: Closing in on the learner’s experience. CALICO Journal, 32(3), 554–568. https://doi.org/10.1558/cj.v32i3.2660

- Li, L. (2017). New technologies and language learning. Palgrave.

- Loewen, S., & Sato, M. (2018). Interaction and instructed second language acquisition. Language Teaching, 51(3), 285–329. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444818000125

- LoopMe. (2021). Lead and follow learning and development. https://www.loopme.io/

- Masche, J., & Le, N. T. (2018). A review of technologies for conversational systems. In Advances in intelligent systems and computing (vol. 629, pp. 212–225). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-61911-8_19

- McTear, M. (2020). Conversational AI: Dialogue systems, conversational agents, and chatbots. Morgan & Claypool Publishers.

- Mills, C., & D’Mello, S. (2014). On the validity of the autobiographical emotional memory task for emotion induction. PLoS One, 9(4), e95837. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0095837

- Pallant, J. (2011). SPSS Survival Manual, A Step by step guide to data analysing using SPSS (4th ed.). Allen & Unwin.

- Reeves, B., & Nass, C. (1996). The media equation. Cambridge University Press.

- Roth, W.-M., & Jornet, A. (2014). Towards a theory of experience. Science Education, 98(1), 106–126. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce21085

- Schroeder, N., Adesope, O., & Gilbert, R. (2013). How effective are pedagogical agents for learning? A meta-analytic review. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 49(1), 1–39. https://doi.org/10.2190/EC.49.1.a

- Schroeder, N. L., & Craig, S. D. (2021). Learning with virtual humans: Introduction to the special issue. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 53(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2020.1863114

- Shadish, W. R., Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (2002). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Stenbom, S., Cleveland-Innes, M., & Hrastinski, S. (2016). Emotional presence in a relationship of inquiry: The case of one-to-one online math coaching. Online Learning, 20(1), 41–57. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v20i1.563

- Swain, M. (2013). The inseparability of cognition and emotion in second language learning. Language Teaching, 46(2), 195–207. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444811000486

- Swedish Research Council. (2017). Good research practice Stockholm: Vetenskapsrådet. https://www.vr.se/download/18.5639980c162791bbfe697882/1555334908942/Good-Research-Practice_VR_2017.pdf

- Timpe-Laughlin, V., Sydorenko, T., & Daurio, P. (2022). Using spoken dialogue technology for L2 speaking practice: What do teachers think? Computer Assisted Language Learning, 35(5–6), 1194–1217. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2020.1774904

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

- Walker, E., & Ogan, A. (2016). We’re in this together: Intentional design of social relationships with AIED systems. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 26(2), 713–729. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-016-0100-5

- Wang, N., & Johnson, W. L. (2008). The politeness effect in an intelligent foreign language tutoring system. In Lecture notes in computer science (including subseries lecture notes in artificial intelligence and lecture notes in bioinformatics) (Vol. 5091 LNCS, pp. 270–280). Springer Verlag. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-69132-7_31

- Wang, X., Pang, H., Wallace, M. P., Wang, Q., & Chen, W. (2022). Learners’ perceived AI presences in AI-supported language learning: A study of AI as a humanized agent from community of inquiry. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2022.2056203