Abstract

This study provides a descriptive analysis of the content and implementation of smartphone policies across 30 secondary schools in England, comparing schools that do (permissive) or do not (restrictive) allow phone use during recreational time. School policy documents were collected, along with survey data from pupil (n = 1198), teacher (n = 53), and SLT (n = 30) participants. Phones were positioned as benefitting safety, learning, and communication. However, most schools adopted restrictive policies, aiming to improve attainment, behavior, and safeguarding. Significant differences were found between pupils and teachers, and between pupils at permissive vs restrictive schools, regarding their support for the rules. Implications are discussed.

Introduction

Smartphones are one of the most-used digital technologies among children and adolescents (age 3–18: Ofcom, Citation2023). Smartphone ownership gradually increases during childhood, but rapidly accelerates in early adolescence (defined as age 10–14: Patton et al., Citation2016). In the UK, by age 12, smartphone ownership is near-universal (98%), and remains so into adulthood (Ofcom, Citation2023); a trend which is reflected in many populations (Pew Research Centre, Citation2023; Roy Morgan Research, Citation2016; UNESCO, Citation2023). This acceleration in smartphone ownership coincides with the transition from primary to secondary school. Hence, the majority of secondary school age children own a smartphone and have access to the multitude of smartphone apps that support communication, information access, organization and management tasks, tracking behaviors, navigation and engagement with entertainment (Goodyear & Armour, Citation2021; Ofcom, Citation2023; UNESCO, Citation2023; Wood et al., Citation2023).

Smartphones can be valuable educational tools when used in schools (UNESCO, Citation2023). Standard smartphone features, including access to the internet, the calculator, a compass, and calendar apps, can aid students with their learning and organizational skills (Thomas et al., Citation2014; Walker, Citation2013). More specific learning apps (e.g. mathematics apps) have been shown to positively impact student performance and engagement (Supandi et al., Citation2018). Social media, which is typically accessed through smartphones, also provides ample opportunities for interaction, collaboration, information access, and resource sharing, that can facilitate an array of learning activities in the classroom, such as: collaborative knowledge construction, relational development, peer support, and social and civic learning (Greenhow & Askari, Citation2015; Greenhow & Lewin, Citation2015). Schools and teachers are also using smartphone apps and social media to communicate with parents and students about school events, accomplishments, and homework (Rutledge et al., Citation2019). Overall, smartphones have been positioned as effective medium through which to enhance student learning and engagement, bridge formal and informal learning contexts, and connect school and home environments (Greenhow & Lewin, Citation2015; Rutledge et al., Citation2019; UNESCO, Citation2023).

There has been considerable debate about whether the positive uses of smartphones within the school setting outweigh the potential for negative impacts (UNESCO, Citation2023). Smartphones have been reported by both teachers and pupils as a source of distraction to learning in the classroom (Berry & Westfall, Citation2015; Thomas et al., Citation2014; Walker, Citation2013). These distractions, caused by going off-topic during phone-based exercises (Chen & Yan, Citation2016; Wikström et al., Citation2022), incoming notifications, and/or even just the presence of a phone (UNESCO, Citation2023), can disrupt lesson flow and cause conflict in the classroom. Smartphones have also been associated with heightened levels of bullying within the school setting (Rose et al., Citation2022; Selwyn & Aagaard, Citation2020; Walker, Citation2013), which can sometimes happen discreetly and is difficult for teachers to detect (Smale et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, smartphones have been reported as a mechanism through which cheating can occur during classes or exams (Birdsong, Citation2017; Gentina et al., Citation2018). There is some concern that smartphones in the classroom may lead to issues with safeguarding, child protection, and privacy (Selwyn & Aagaard, Citation2020; UNESCO, Citation2023). However, these latter concerns are largely reported in policy documents/guidance, and so far, there is little empirical evidence to support these claims about negative impacts.

School smartphone policies

There is no universal level of agreement on how schools should manage the presence of smartphones among students during the school day (UNESCO, Citation2023; Wikström et al., Citation2022). In the last few years, there has been a growing international trend for the use of phones to be prohibited in schools and classrooms (Selwyn & Aagaard, Citation2020). Several countries, including France, Israel, Turkey, and regions of Canada and Australia, have introduced policies that mandate public schools to prohibit smartphone use during the school day (Selwyn & Aagaard, Citation2020; UNESCO, Citation2023). Whilst a recent report by the UN highlighted that almost a quarter of countries worldwide have implemented phone bans (UNESCO, Citation2023) other countries such as the UK, have no such top-down government policy. The UK Government has recently provided guidance on how to limit phone use during the day (Department for Education, Citation2024), however prohibiting phone use in schools is not part of statutory law. Prior to this guidance, many schools had already opted to devise their own policies that restrict phone use during the school day (Department for Education, Citation2020; Science Innovation & Technology Committee, 2019; Wood et al., Citation2023). These restrictive phone use policies are based on popular assumptions that restricting phone use will improve educational attainment and wellbeing, and reduce the prevalence of addictive behaviors and cyberbullying (Goodyear & Armour, Citation2021; Selwyn & Aagaard, Citation2020). However, there is little evidence to support these assumptions, with only a small number of studies indicating positive effects on student attainment, which are primarily focussed on improving attainment in low achieving students (Beland & Murphy, Citation2016; Beneito & Vicente-Chirivella, Citation2022; Selwyn & Aagaard, Citation2020).

Whether the features of school policies are influenced by top-down (e.g. legislative rules, national standards, government guidance or curricula) or bottom up (e.g. school-driven circumstances, needs) priorities, the development and implementation of school policies and practices are highly localized (Goodyear et al., Citation2016; Wikström et al., Citation2022). From a policy enactment perspective, policy is seen as a dynamic and multi-lateral process that emerges at the interface of practices, actions, interpretations and translations across different levels and people within schools (Ball et al., Citation2011; Wikström et al., Citation2022). In relation to policy development, the content and design of school policies are influenced by a range of factors, including: schools’ values and priorities, leadership structure and style, pupil demographics and behavior, and the extent of family and community involvement with the school (Ball, Citation2017; Ball et al., Citation2011). Implementation and enactment process models identify that how a policy exists in practice is shaped by social processes, including: senior leadership support for the policy, communication of the policy, education/training about the policy, how teachers are supported to enact the policy, and whether the policy is perceived by members of the school to be reasonable and relevant (Ball, Citation2017; Ball et al., Citation2011; Maguire et al., Citation2015). Overall, the perceived level of ownership and the level of support for the school’s policy are key factors influencing the level of compliance by teachers and students (Ball, Citation2017; Maguire et al., Citation2015). Thus, policies that are developed from the ‘bottom up’ and have high levels of ‘buy in’ are more likely to be followed (Ball, Citation2017; Maguire et al., Citation2015).

At national and international levels, there have been renewed calls to provide schools with evidence-based guidance to inform the development of school policies on phone use (Science Innovation & Technology Committee, 2019). Many schools and teachers report that they are confused and uncertain about how to manage and support student phone use during the school day (Goodyear & Armour, Citation2021; Selwyn & Aagaard, Citation2020). Students have also suggested that they need better guidance on what phone use is permitted during the school day, and that there should be clarity on the role of phones in learning (Goodyear & Armour, Citation2021). In order to facilitate decisions about how to manage and support phone use within schools, better understanding is needed on the content and implementation of school phone use policies.

This paper provides a descriptive analysis of secondary school smartphone policies in England. We do this by providing a comparison of the content and implementation of school phone policies in schools that either do allow phone use during school recreational time (permissive phone policies) or that do not permit this (restrictive phone policies). The research questions were:

What is the content of restrictive and permissive school smartphone policies?

How are restrictive and permissive school smartphone policies implemented?

Methods

The data reported in this paper is part of a wider project, the SMART Schools study (Wood et al., Citation2023), which was designed to explore the impact of school daytime restrictions of smartphone and social media use on adolescent mental wellbeing, and other associated health and behavioral outcomes (e.g. sleep, physical activity, disruptive classroom behavior and attainment). Full details of the SMART Schools Study are described in the protocol (Wood et al., Citation2023). Briefly, the SMART Schools study is an observational natural experimental study using multiple methods, in which two groups of schools were compared based on whether their phone policies were restrictive or permissive. Within the study, pupil participants aged 12–13 (year 8) and 14–15 (year 10), school staff (teachers, Senior Leadership Team [SLT] and support staff), and parents from 30 secondary schools across England were recruited between October 2022 and November 2023. This paper presents an analysis of the school policy documents that were collected from the 30 participating schools and survey data from pupil, teacher, and SLT participants. Ethical approval was granted from the University of Birmingham Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics Ethics Review Committee [ERN_22-0723] and all methods were conducted with the provisions within the ethical approval. All participants consented to taking part. School and participant data were anonymised during the analysis and reporting of the findings.

Co-production methods

Adolescent (n = 19, age 11–14) and school staff advisory groups who were not part of the main study sample (n = 5, including 1 member of SLT, 3 secondary school teachers and 1 school governor), helped to design recruitment approaches and material, and co-produce the methods of data collection. All participants were external to the study population and were compensated for their participation. All adolescents were from the same school, and participated in two workshops within their school. School staff were from different schools across England, and attended two online workshops. Specifically, the advisory groups were consulted on: (a) recruitment approaches, and content of flyers and video; (b) the definition of permissive and restrictive school policy contexts; (c) school policy documents to be collected and the most appropriate method of data collection (e.g. website, email, and/or via specific school staff); and (d) survey questions. The data collection methods were also piloted with these groups. Overall, the advisory groups helped to ensure methodological rigor, by facilitating pathways of communication for recruitment and ensuring that the data collection methods could answer the study research questions, while being clear and transparent to the study’s participants.

School sample

The initial sampling frame for the SMART Schools Study consisted of 1345 secondary schools across England, which were categorized as 125 permissive schools and 1220 restrictive schools (Wood et al., Citation2023). Schools were categorized by the research team, as per the definition of permissive and restrictive schools (Wood et al., Citation2023), using publicly available information accessed from each school’s website (e.g. policy documents). During the course of recruitment, it was found that a number of schools had since changed policy, or were incorrectly classified due to outdated policies on school websites, and thus our final sampling frame consisted of 1341 eligible schools: comprising 96 permissive schools and 1245 restrictive schools. A stratified sampling approach was used, based on propensity scores (strata were defined using propensity score tercile cutpoints) (Rubin, Citation1997). Propensity scores were developed using the categorisations of restrictive or permissive school policies and this was regressed on school characteristics obtained from routine data provided by the Department for Education [DfE] (e.g. school size, school type). A sample size of 30 secondary schools (20 restrictive and 10 permissive) was determined based on effect sizes related to the wider SMART School’s Study primary outcome of mental wellbeing (Wood et al., Citation2023).

Data collection methods and analysis

School policy documents

Data collection

Data from school policy documents were collected to provide a detailed description of the content and implementation features of school smartphone policies. The parameters of the documents obtained from schools (Dalglish et al., Citation2020; Schreier, Citation2014) was set at the level of statutory and non-statutory school policies that described the rules related to smartphone use during the school day. School policies that met these criteria were downloaded from school websites or collected from the school study liaison member of staff.

Data analysis

Qualitative content analysis was used to extract and analyze the data from the school policy documents (Schreier, Citation2014). An initial coding frame was developed in a data-driven way using a sub-set of data from three randomly sampled schools (1 permissive and 2 restrictive) (Schreier, Citation2014), and by employing the strategy of comparing and contrasting (Boyatzis, Citation1998). The coding frame was then piloted and modified (Schreier, Citation2014). In the process of piloting, the authors refined the descriptions of the codes and merged some of the categories. Following this, reliability tests were completed. In this process, the school policies from a sub-sample of three additional (1 permissive, 2 restrictive) schools were coded separately by two coders using NVivo 20 software. Inter-rater and intra-rater reliability scores of above 85% (van der Mars, Citation1998) confirmed that the frame could be used in the main analysis. The final coding frame developed following this process consisted of 10 categories and 29 sub-categories (see Supplementary File 1) and was applied to the policy documents collected from the 30 schools. Consistent with the qualitative content analysis approach (Schreier, Citation2014), the coding frame development and its application to the policies are the main stages of the analytical process. In the results, extracts from the frame and illustrative quotes are presented alongside survey data.

Surveys

Data collection

Data used in this paper are from questions in the pupil, teacher, and SLT surveys relating to the design and implementation of each school’s phone policy. Questions were developed in a concept driven way and were informed by policy enactment theory (Ball et al., Citation2011), focussing mainly on acceptability, compliance, and policy communication. All pupil, teacher and SLT participants completed questions related to acceptability of, and compliance with the policy. Participants were asked to record on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = Neutral, 4 = agree, and 5 = Strongly agree) the extent to which school phone rules were understood, supported, and followed (Supplementary File 2). Further data were collected from the SLT survey on the design of the school’s phone policy (e.g. rationale and rules) and policy communication (Supplementary File 2). All surveys were completed online using an approved server (REDCap); pupils completed the survey on encrypted tablets during lesson time, using a portable Wi-Fi hub owned by the research team. Teachers and SLT were sent a link to complete the survey in their own time.

Data analysis

Survey data was downloaded from REDCap into excel, where it was cleaned, and prepared for analysis. Quantitative analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Version 29. Descriptive statistics (frequencies and percentages) were used to summarize categorical data. Mann–Whitney U tests were used to compare differences between groups in survey responses relating to whether school phone policies were understood, supported, and followed. Responses from SLT and teachers were combined, to form ‘teacher responses’, and these were compared with pupil responses. Comparisons were also made between teachers at permissive schools vs restrictive schools, and between pupils at permissive schools vs restrictive schools. Within the SLT survey, several participants used the free text response boxes to provide additional information regarding their policies and rationale. Anonymised text from these is used in the results section to further illustrate findings where appropriate.

Results

Sample characteristics

The characteristics of the 30 secondary schools that were recruited for the SMART Schools Study are reported in . Across restrictive and permissive school groups, the school characteristics were broadly similar, but a higher proportion of permissive schools were single sex schools, faith schools and had a selective admissions policy.

Table 1. School sample characteristics.

In this paper, survey data (Supplementary file 2) is reported from the sample of 30 schools (1198 pupils, 53 teachers, and 30 SLT members). There is a high level of data completeness for SLT (100%, 30 SLT/30 schools), teachers (88.3%, 53/60: target 2 teachers per school), and pupils (96.8%, 1198 of the 1237 pupils participating in the SMART Schools Study).

Participant characteristics are reported in . Within the SLT sample, the majority were assistant headteachers (15/30: 50%) and deputy headteachers (9/30: 30%). Those completing the teacher survey were mainly form tutors and/or heads of year for year 8 (age 12–13) and year 10 (age 14–15), and taught a wide range of subjects.

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of participants.

Policy documents

shows the type and number of documents collected and analyzed across the 30 participating schools. These indicate that smartphones, and/or the school rules relating to them, are mentioned in a wide range of school policies, in both permissive and restrictive schools.

Table 3. Policy documents included in the document analysis.

Findings

Using data from the document analysis and surveys, this section outlines; (a) the design and development of school smartphone policies, including the policy types and rationales given for them; and (b) the implementation of school policies, including how they are communicated to pupils, the sanctions for non-adherence, and the acceptability and compliance levels of these policies by pupils, teachers and SLT.

Design and development of school smartphone policies

Smartphone policy types

The document analysis revealed that there were four main types of phone policies within the permissive and restrictive phone policy categories. These are shown in , along with illustrative quotes. Policy types 1 and 2 were classed as ‘permissive policies’ and varied by the amount of time pupils were allowed on their smartphone during the school day (use anytime vs use at designated times). Policy types 3 and 4 were classed as ‘restrictive policies’ and varied by whether smartphones were accessible to pupils (accessible in bags vs not allowed on person).

Table 4. Different types of school phone policies.

In addition to these policies, which stipulate recreational smartphone use at school, some schools in the sample allowed smartphones to be used for educational purposes during the school day. According to data from the SLT survey, almost two thirds of schools (19/30: 63.3%) permitted smartphone use during lessons with consent from the teacher (9 restrictive Schools (45%) and 10 permissive schools (100%)). Key educational activities identified were: accessing quizzing appsFootnote1 (15 schools) and homework appsFootnote2 (10 schools) or using phones to take photos of the board/their work (13 schools). In , the example quote for policy type 4a shows how some schools wrote this permitted use of smartphones for educational purposes into their school phone policy.

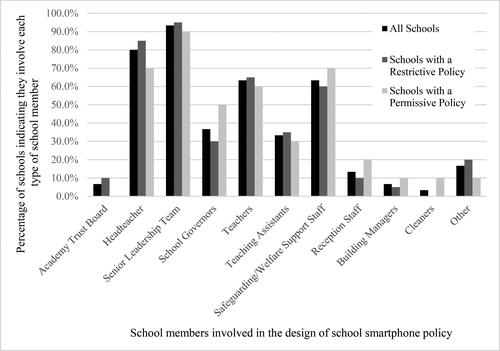

Policy design

As part of the SLT survey, participants were asked about which groups or individuals were involved in the design of their smartphone policy (). SLT were mostly involved (28/30 schools; 93.3%), followed by the headteacher (24/30; 80.0%). Teachers and safeguarding/welfare support staff were also often consulted in the majority of the schools, (19/30; 63.3%). The SLT participants in five schools indicated that ‘other’ groups/individuals were involved in the design of their phone policies, and in 3 of these schools (3/30; 10.0%) this included ‘students’. These 3 schools all had restrictive phone policies. There were few other differences between restrictive and permissive schools regarding who was involved in the design of their policies.

Location of and rationale for smartphone policy

The content analysis identified the location of the smartphone policy within the school’s policy documentation (). Only 10 schools (33.3%) had a specific smartphone policy document, most others (19/30; 63.3%) included their phone rules within other policy documents, and one school had no policy. A higher proportion of permissive schools had a separate smartphone policy than restrictive schools. Of the schools that did not have a specific smartphone policy, the rules around smartphone use most often appeared in the school behavior policy (19 schools), and in a third of schools, the rules were reiterated in multiple policies (e.g. Safeguarding and IT).

Table 5. Location of smartphone policies.

Thirteen schools (43.3%) included a rationale for their choice of smartphone rules (). This included all 10 schools with a separate smartphone policy. Analysis of the rationales indicated that there were 4 main categories; benefits, harms, benefits and harms, and safety provided by smartphones. The results of this analysis, including subcategories and illustrative quotes, are shown in .

Table 6. Rationales for school smartphone policies.

As part of the SLT survey, participants reported how long their current policies had been in place (). When excluding missing data, most policies (13/24: 54.2%) were introduced in the 2 years prior to data collection: 2020–2021. When asked about any previous smartphone policies, 5 restrictive schools indicated that they used to have a permissive policy, and 1 permissive school indicated that they used to have a restrictive policy.

Table 7. Time current smartphone policies have been in place.

Some SLT participants provided free-text responses regarding their school’s decision to change their smartphone policy. An example from both a restrictive and permissive school is provided:

When we reviewed the original one many students commented that just having it on in their pocket was enough to distract them from learning because they felt they had to keep up with what was going on. This also affected their mental health. (SLT: restrictive school).

Teach the students to use the technology responsibly – they are now a part of everyday life and restricting their use in school is not preparing them for life outside of school. (SLT: permissive school).

Implementation of school smartphone policies

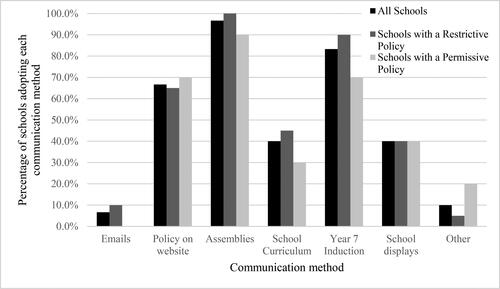

Communication of policies to pupils

Schools communicated their policies to pupils in several ways, as shown in . The most popular method, indicated by 96.7% of SLT (29/30) was to inform pupils during school assemblies, which represents a verbal form of policy communication. Policies were also often communicated to pupils when they first start at the school, as part of their year 7 (age 11–12) induction (25/30; 83.3%). The majority of schools (20/30; 66.7%) also indicated that their policy was available on the school website. There was little difference between restrictive and permissive schools in how they communicated their policies to pupils.

Implementation of smartphone policies

The members of staff primarily involved in implementing school phone policies across the schools were teachers, SLT, and safeguarding/welfare support staff (100, 96.7, and 93.3% respectively). Teaching assistants (80.0%), headteachers (70.0%), and reception staff (70.0%) were also commonly involved.

To ensure pupils adhered to the rules, schools had in place behavioral sanctions for noncompliance. As reported in the SLT survey, if students did not follow the rules for smartphone use their phone would be confiscated in all schools (n = 30). Many (18/30) schools stated that in addition to phone confiscation they would contact the pupil’s parent/guardian. The document analysis corroborated these findings, showing that confiscation was the main sanction for noncompliance of school phone rules. Both the document analysis and the SLT survey identified that most schools employed an escalation approach to noncompliance. Schools tended to increase the length of confiscation for repeat offenses (e.g. 1 day vs. 1 week), incorporate detentions, and/or contact parents to collect their child’s phone from the school premises. See example quotes below:

1st incident – confiscation until end of day, repeat incident – confiscation for 24 hours (SLT, survey response, restrictive school).

When a student misuses their devices, for example having a mobile phone out in class, it will be confiscated and returned to the student that day. For repeated incidents of mobile phone misuse the phone will be confiscated, placed in the safe and not returned until a parent or carer comes into school to collect it. (Document Analysis, Behaviour policy, permissive school).

Acceptability and compliance of policies

As shown in there were significant differences between the teachers/SLT and pupils in their levels of agreement toward whether the rules were understood, supported, and followed by pupils and teachers. Pupils showed significantly lower agreement than teachers/SLT that pupils in their school understand (p < 0.001), support (p < 0.001), and follow (p < 0.001) the school smartphone rules. Pupils showed significantly lower agreement than teachers/SLT that the teachers at their school understand (p < 0.001), support (p < 0.001), and enforce that pupils follow the rules (p = 0.002).

Table 8. Differences in viewing smartphone policies among teachers and pupils.

shows responses compared for pupils in schools with a restrictive smartphone policy and pupils in schools with a permissive smartphone policy, between which there were significant differences on several items. Pupils in permissive schools showed significantly lower agreement than pupils in restrictive schools, that most teachers understand the school phone rules (p = 0.003). However, pupils in permissive schools showed significantly higher agreement than pupils in restrictive schools, that most pupils support the school phone rules (p < 0.001), and that most pupils follow the school phone rules (p = 0.002).

Table 9. Differences in viewing smartphone policies among pupils in schools with restrictive compared to permissive policies.

Finally, the responses from teachers and SLT combined in schools with restrictive compared with permissive smartphone policies, showed several significant differences (). Teachers/SLT in restrictive schools showed significantly higher agreement than those in permissive schools, that most pupils understand the school phone rules (p = 0.021). Furthermore, teachers/SLT in restrictive schools showed significantly higher agreement than those in permissive schools that most teachers support (p = 0.003), and ensure the pupils follow (p = 0.004) the school phone rules.

Table 10. Differences in viewing smartphone policies among teachers in schools with restrictive compared to permissive policies.

Discussion

This paper provides evidence on the content and implementation of school smartphone policies in England. The findings illustrate that most schools restrict how adolescents use their phones, with very few permitting phones to be used at any time within the school day. In the study sample, approaches to restricting phone use varied; with some schools prohibiting phones on premises altogether, others requiring pupils to turn phones off in their bags, some purchasing commercial pouches for pupils to lock their phones away, and other schools permitting the use of phones at certain times during the school day (e.g. at lunch or break). However, in the last few years the overwhelming direction of travel has been for schools to introduce policies that restrict phone use throughout the school day, as evidenced by the change of this study’s sampling frame.

The rationales and rules for restrictive and permissive phone policies were underpinned by justifications that the benefits of phone use are only realized in certain contexts and at certain times in the day. For example, phones support the safety of adolescents when traveling to and from school; phones are beneficial for learning in classrooms when use is sanctioned by a teacher; and phones can support communication at recreational times. Equally, schools justified restricting phone use at certain times of the day to minimize risks to attainment, reduce incidents of disruptive behavior, and to safeguard adolescents. In relation to the perceived effectiveness of school phone policies, the findings emphasize the importance of establishing coherence between policy development and implementation. Most schools adopted a top-down approach to the design of school phone policies, with SLT leading policy development and students rarely consulted. In practice, SLT/teachers and students had different perceptions about restrictive and permissive phone policies. For example, SLT and teachers in schools with restrictive phone policies perceived that teachers were more supportive of the school phone rules compared with permissive schools. Students in restrictive school policy contexts were less likely to agree that pupils in their school supported and followed the school phone rules compared with pupils in permissive school policy contexts. The key challenge therefore for schools is to design phone policies that restrict phone use in ways that can maximize benefits, minimize the potential risks and generate ‘buy in’ from all members of a school: SLT, teachers and students.

For a number of decades, the narratives surrounding adolescents, smartphones, and social media have been predominantly risk-based and this has materialized in schools through their adoption of risk-aversion policies and practices, such as school phone ‘bans’ (Goodyear & Armour, Citation2021; Selwyn & Aagaard, Citation2020). New evidence from this study on secondary school phone policies in England, indicates that many schools implemented more restrictive phone policies around the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, the shift toward greater levels of reliance on phones for communication and information during this time, alongside heightened concerns for health and wellbeing (Goodyear et al., Citation2021), may have been influencing factors. However, this study also provides new evidence that as well as these negative perspectives, there is an appreciation and acknowledgement of the benefits of phones in adolescents’ daily lives, and the need for schools to develop adolescents’ skills to support phone use outside of school.

Recent studies in Sweden (Wikström et al., Citation2022) and Greece (Nikolopoulou, Citation2020) have also reported on the benefits of smartphones cited by some teachers, including their use as a potential classroom resource, and the ability of the technology to support teaching while also keeping the students engaged and motivated. This positive turn also mirrors trends in the growing parental acceptance of technology in adolescents’ lives, and in particular the benefits of phones/social media for security and monitoring (Burnell et al., Citation2023; Perowne & Gutman, Citation2023). Although teachers and parents are becoming more accepting of the benefits of phone use, there is some evidence from this study to suggest that students accept having some boundaries of phone use during the school day. For example, when students were consulted on the school phone policy rules, they indicated a preference for rules around the use of phones within the classroom to prevent them from becoming a distraction to learning. This is similar to quantitative findings in adolescents in China (Gao et al., Citation2017) and qualitative findings in adolescents in the UK (Rose et al., Citation2022; Walker, Citation2013), who reiterated their potential for distraction during lessons. In most permissive and restrictive schools in this study, however, phone use was permitted during lessons for educational activities if sanctioned by the teacher. Hence, there is some indication of contradictions on the perceived value of phones for learning between teachers and students, with students tending to be in favor of rules that limit their use in the classroom. Building on prior research (Gao et al., Citation2017), evidence from this study suggests that rather than simply prohibiting phone use during the school day, the challenge for schools is to develop more balanced and collaborative approaches to phone use, and that resemble a middle ground between a blanket ban and unstructured use.

Across both permissive and restrictive phone policy contexts, the rules for phone use tended to be communicated verbally and the main consequence of phone misuse was confiscation. Furthermore, in both policy contexts, teachers tended to overestimate the extent to which they perceived students understood and/or followed the rules. The data from this study therefore suggests that regardless of the phone policy type, the rules around phone use need to be clearly communicated to students. This message is consistent with the UN’s argument for schools to provide greater clarity and transparency on the required behaviors for phones in schools, and the UN caution against punishing students in the absence of clear guidance on what is and what is not permitted (UNESCO, Citation2023). Similarly, the DfE in the UK encourage headteachers to ensure that phone rules are applied consistently and fairly and recommend that the rules around phone use are re-iterated to all students, staff, and parents throughout the year (Department for Education, Citation2022). This suggestion by the DfE considers time as a key factor in realizing policy enactments, where at certain times in the academic year policies are high profile (e.g. at the start of the year, or as part of year 7 induction) and then they move to the background at other times (Braun et al., Citation2010). Evidence from the US suggests that the type of consequences for misuse influences adherence, where more confrontational consequences (e.g. being removed from class) were reported to be more effective than verbal warnings (Berry & Westfall, Citation2015). In the context of implementation, our analysis suggests that schools need to establish clear and effective pathways of communication on phone rules, and establish relatively ‘strict’ rules for phone misuse to enhance adherence.

Drawing on the data from this study, and implementation and process enactment models (Ball et al., Citation2011; Braun et al., Citation2010; Maguire et al., Citation2015), school phone policies will be more effective when students, teachers, and SLT members have a perceived level of ownership over the policy. Overall, people tend to be more supportive of rules if they have been involved in designing them (Bonell et al., Citation2013). Furthermore, it is important to contextualize policies in the needs of the local context (Braun et al., Citation2010; Goodyear et al., Citation2016), particularly given that pupil demographics and behavior, and schools’ values and priorities are well-established contextual factors that influence acceptance and compliance of school policies and practices (Ball et al., Citation2011; Goodyear et al., Citation2016; Maguire et al., Citation2015). To illustrate this point, and based on this study’s sample characteristics, more permissive phone policies tend to align with schools that have single sex and selective admissions policies. Nonetheless, wholly top-down or bottom-up approaches to the development and implementation of school policies and practices are rarely effective (Braun et al., Citation2010; Goodyear et al., Citation2016; Macdonald, Citation2003). The fidelity of implementation and compliance are key concerns in top-down approaches, and although bottom-up approaches prioritize local expertise that enhance fidelity and compliance, they tend to be poorly resourced and lose systemic attention over time (Victoria A. Goodyear et al., Citation2016; Macdonald, Citation2003). Collaborative approaches to policy development that engage with government, schools and school leaders, researchers and evidence, and student and parent communities can overcome the aforementioned challenges (Goodyear et al., Citation2016; Macdonald, Citation2003). All of this suggests that governments have a role to play in advising schools and disseminating evidence-based guidance on phone use policies to support headteachers in devising such policies within their local communities of SLT, teachers, students, and parents.

Strengths and limitations

This mixed methods study provides a multi-layered account from diverse perspectives on how school phone policies are positioned, designed, and implemented, and how key players (teachers, SLT and students) perceive the acceptability of these rules. Among the recruited schools, there is a high level of data completeness from the target participants, thus providing considerable data on which comparisons can be made. There is also relative balance in the sample characteristics between permissive and restrictive schools, therefore enhancing comparability. However, there was a lack of preexisting measures of policy perceptions on which to draw on for the participant surveys, and they were therefore newly devised for this study. While all surveys were piloted as part of the co-production process and were deemed to be relevant, clear, and comprehensive, it was found during analysis that in some areas they lacked depth, and therefore were unable to provide enough detail to explain factors and differences between school types (e.g. participants were asked to report on their perception of the school population, rather than their own behaviors). Hence, future research should aim to devise robust measures for policy perceptions, which would enable an analysis of the relationships between factors. It may also be appropriate to seek the perceptions of parents toward school phone policies, as they have previously been identified as one of the ‘key players’, along with pupils and teachers, as they have a ‘mediating’ role in the complex social system upon which school phone policies are built (Gao et al., Citation2017).

Implications

This study provides evidence to inform the development of robust guidance for schools on how they can design and implement phone use policies. The findings suggest that schools have a role to play in supporting adolescents to use phones safely and effectively, and school policies that include some level of moderation on when and how phones are used is supported by SLT, teachers, and students. Future government policy should carefully consider whether a blanket ban is the most appropriate approach, and the extent to which structured guidance or exemplars of permissive and restrictive school policies would be of value to schools to ensure policy effectiveness. There is also a need to reconsider top-down approaches to the development of school phone policies, and provide schools with the autonomy to co-design approaches with students to enhance acceptability and compliance. Future research should explore the impact of school policies on educational outcomes, and other mental and physical outcomes, to determine the extent to which school policies are beneficial for adolescents. Furthermore, an economic analysis of the implementation of school phone policies could provide detailed insights into whether these policies are cost-effective approaches to learning and mental and physical wellbeing.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (74.5 KB)Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the study advisory boards, including the Study Steering Committee and the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee. We would also like to thank other members of the research team that were involved in the data collection and preparation, including David Alexander and Grace Wood. Finally, we would like to thank the schools and participants for their contributions and engagement with the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Amie Randhawa

Amie Randhawa is a Research Fellow in the School of Sport, Exercise and Rehabilitation Sciences and the Institute for Mental Health at the University of Birmingham. Her research interests include applying qualitative and quantitative methods to the study of adolescent health and well-being, with particular interest in young people’s uses of smartphones and social media. Twitter: @RandhawaAmie

Miranda Pallan

Miranda Pallan is a professor of child and adolescent public health in the Institute of Applied Health Research at the University of Birmingham. Her research interest include the epidemiology, prevention and management of overweight and obesity in children, school food provision and environments, and adolescent nutrition, mental wellbeing and physical activity. Twitter: @MirandaPallan

Rebecca Twardochleb

Rebecca Twardochleb is a Research Associate in the School of Sport, Exercise and Rehabilitation Sciences and the Institute for Mental Health at the University of Birmingham. Her research interests include sports psychology and adolescents’ uses of smartphones and social media. Twitter: @beckytward

Peymane Adab

Peymane Adab is a professor of chronic disease epidemiology and public health in the Institute of Applied Health Research at the University of Birmingham. Her research interests are in chronic disease epidemiology and behavioural medicine. She has expertise in using mixed methods to aid the development and evaluation of complex interventions. Twitter: @Peymane_Adab

Hareth Al-Janabi

Hareth Al-Janabi is a professor of health economics in the Institute of Applied Health Research at the University of Birmingham. His current interest is in studying real-world resource allocation decisions, and his research covers several fields, including informal care, social care, public health, mental health, end-of-life, education, and workplaces. Twitter: @hajbrum

Sally Fenton

Sally Fenton is an associate professor in lifestyle behaviour change in the School of Sport, Exercise and Rehabilitation Sciences at the University of Birmingham. Her research is focused on the development, delivery and evaluation of theory-based interventions to promote physical activity, with an emphasis on clinical populations. Twitter: @Sal_Fenton

Kirsty Jones

Kirsty Jones is the Head of School Support at Services For Education, Birmingham, UK. She has over 20-years’ experience in school leadership spanning mainstream, special schools and alternative provision settings working with schools with both disadvantaged children and high attaining pupils.

Maria Michail

Maria Michail is an associate professor in the School of Psychology and the Institute for Mental Health at the University of Birmingham. She is a leading expert in the field of self-harm and suicide prevention, and her work has had demonstrable impact on improved clinical practice across primary care in the UK. Twitter: @mariamichail2

Paul Patterson

Paul Patterson is the Public Mental Health Lead at Forward Thinking Birmingham, Birmingham Women’s and Children’s NHS Foundation Trust and is a member of the and the Institute for Mental Health at the University of Birmingham. His interests include improving emotional resilience and wellbeing, early intervention & prevention of mental disorder.

Alice Sitch

Alice Sitch is a Senior Lecturer working in the Institute of Applied Health Research at the University of Birmingham. Her main research interests are in the area of designing and evaluating monitoring tests and studies of biological variability. Twitter: @alicesitch

Matthew Wade

Matthew Wade is the Head of Research and Development at ukactive, London, UK, and a visiting researcher at the Advanced Wellbeing Research Centre, Sheffield Hallam University. He has extensive experience in physical-activity based research and evaluation across various populations.

Victoria A. Goodyear

Victoria A. Goodyear is an associate professor in pedagogy in sport, physical activity and health in the School of Sport, Exercise and Rehabilitation Sciences and the Institute for Mental Health at the University of Birmingham. Her main research area focuses on social media/digital technologies and young people’s health and wellbeing, and she is interested in the professional learning needs of teachers/coaches. Twitter: @VGoodyear

Notes

1 For example, Kahoot, Seneca.

2 For example, Class Charts, Show My Homework.

References

- Ball, S. (2017). The education debate (3rd ed.). Policy Press.

- Ball, S., Maguire, M., & Braun, A. (2011). How schools do policy: Policy enactments in secondary schools. Routledge.

- Beland, L., & Murphy, R. (2016). Ill communication: Technology, distraction & student performance. Labour Economics, 41, 61–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2016.04.004

- Beneito, P., & Vicente-Chirivella, Ó. (2022). Banning mobile phones in schools: Evidence from regional-level policies in Spain. Applied Economic Analysis, 30(90), 153–175. https://doi.org/10.1108/AEA-05-2021-0112

- Berry, M. J., & Westfall, A. (2015). Dial D for distraction: The making and breaking of cell phone policies in the college classroom. College Teaching, 63(2), 62–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.2015.1005040

- Birdsong, T. (2017). Survey: Kids using devices in school for more than just learning. Retrieved 10/11/2023 from https://www.mcafee.com/blogs/family-safety/using-devices-to-cheat-in-school/.

- Bonell, C., Jamal, F., Harden, A., Wells, H., Parry, W., Fletcher, A., Petticrew, M., Thomas, J., Whitehead, M., Campbell, R., Murphy, S., & Moore, L. (2013). Systematic review of the effects of schools and school environment interventions on health: Evidence mapping and synthesis. Public Health Research, 1(1), 1–320. https://doi.org/10.3310/phr01010

- Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Sage.

- Braun, A., Maguire, M., & Ball, S. J. (2010). Policy enactments in the UK secondary school: Examining policy, practice and school positioning. Journal of Education Policy, 25(4), 547–560. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680931003698544

- Burnell, K., Andrade, F. C., Kwiatek, S. M., & Hoyle, R. H. (2023). Digital location tracking: A preliminary investigation of parents’ use of digital technology to monitor their adolescent’s location. Journal of Family Psychology, 37(4), 561–567. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0001067

- Chen, Q., & Yan, Z. (2016). Does multitasking with mobile phones affect learning? A review. Computers in Human Behavior, 54, 34–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.07.047

- Dalglish, S. L., Khalid, H., & McMahon, S. A. (2020). Document analysis in health policy research: The READ approach. Health Policy and Planning, 35(10), 1424–1431. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czaa064

- Department for Education. (2020). School snapshot survey: Winter 2019. Retrieved 10/11/2023 from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/school-snapshot-survey-winter-2019.

- Department for Education. (2022). Behaviour in schools: Advice for headteachers and school staff: UK Government. Retrieved 10/11/2023 from: https://consult.education.gov.uk/school-absence-and-exclusions-team/revised-school-behaviour-and-exclusion-guidance/supporting_documents/Behaviour%20in%20schools%20%20advice%20for%20headteachers%20and%20school%20staff.pdf

- Department for Education. (2024). Mobile phones in schools: Guidance for schools on prohibiting the use of mobile phones throughout the school day. Retrieved 27/02/2024 from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/65cf5f2a4239310011b7b916/Mobile_phones_in_schools_guidance.pdf.

- Gao, Q., Yan, Z., Wei, C., Liang, Y., & Mo, L. (2017). Three different roles, five different aspects: Differences and similarities in viewing school mobile phone policies among teachers, parents, and students. Computers & Education, 106, 13–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2016.11.007

- Gentina, E., Tang, T. L.-P., & Dancoine, P.-F. (2018). Does Gen Z’s emotional intelligence promote iCheating (cheating with iPhone) yet curb iCheating through reduced nomophobia? Computers & Education, 126, 231–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.07.011

- Goodyear, V. A., & Armour, K. M. (2021). Young People’s health-related learning through social media: What do teachers need to know? Teaching and Teacher Education, 102, 103340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103340

- Goodyear, V. A., Boardley, I., Chiou, S.-Y., Fenton, S. A. M., Makopoulou, K., Stathi, A., Wallis, G. A., Veldhuijzen van Zanten, J. J. C. S., & Thompson, J. L. (2021). Social media use informing behaviours related to physical activity, diet and quality of life during COVID-19: A mixed methods study. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1333. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11398-0

- Goodyear, V. A., Casey, A., & Kirk, D. (2016). Practice architectures and sustainable curriculum renewal. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 49(2), 235–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2016.1149223

- Greenhow, C., & Askari, E. (2015). Learning and teaching with social network sites: A decade of research in K-12 related education. Education and Information Technologies, 22(2), 623–645. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-015-9446-9

- Greenhow, C., & Lewin, C. (2015). Social media and education: Reconceptualizing the boundaries of formal and informal learning. Learning, Media and Technology, 41(1), 6–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2015.1064954

- Macdonald, D. (2003). Curriculum change and the post-modern world: Is the school curriculum-reform movement an anachronism? Journal of Curriculum Studies, 35(2), 139–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220270210157605

- Maguire, M., Braun, A., & Ball, S. (2015). ‘Where you stand depends on where you sit’: The social construction of policy enactments in the (English) secondary school. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 36(4), 485–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2014.977022

- Nikolopoulou, K. (2020). Secondary education teachers’ perceptions of mobile phone and tablet use in classrooms: Benefits, constraints and concerns. Journal of Computers in Education, 7(2), 257–275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40692-020-00156-7

- Ofcom. (2023). Children and parents: Media use and attitudes. Retrieved 17/01/2024 from https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0027/255852/childrens-media-use-and-attitudes-report-2023.pdf.

- Patton, G. C., Sawyer, S. M., Santelli, J. S., Ross, D. A., Afifi, R., Allen, N. B., Arora, M., Azzopardi, P., Baldwin, W., Bonell, C., Kakuma, R., Kennedy, E., Mahon, J., McGovern, T., Mokdad, A. H., Patel, V., Petroni, S., Reavley, N., Taiwo, K., … Viner, R. M. (2016). Our future: A Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. Lancet, 387(10036), 2423–2478. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00579-1

- Perowne, R., & Gutman, L. M. (2023). Parents’ perspectives on smartphone acquisition amongst 9-to 12-year-old children in the UK–a behaviour change approach. Journal of Family Studies, 30, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2023.2207563

- Pew Research Centre. (2023). Teens, social media and technology 2023. Retrieved 10/11/2023 from https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2023/12/11/teens-social-media-and-technology-2023/.

- Rose, S. E., Gears, A., & Taylor, J. (2022). What are parents’ and children’s co-constructed views on mobile phone use and policies in school? Children & Society, 36(6), 1418–1433. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12583

- Roy Morgan Research. (2016). 9 In 10 Aussie teens now have a mobile (and most are already on to their second or subsequent handset). Retrieved 10/11/2023 from https://roymorgan-cms-dev.s3.ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/17003545/6929-australian-teenagers-and-their-mobile-phones-june-2016-1.pdf.

- Rubin, D. B. (1997). Estimating causal effects from large data sets using propensity scores. Annals of Internal Medicine, 127(8 Pt 2), 757–763. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-127-8_part_2-199710151-00064

- Rutledge, S. A., Dennen, V. P., & Bagdy, L. M. (2019). Exploring adolescent social media use in a high school: Tweeting teens in a bell schedule world. Teacher’s College Record, 121(14), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811912101407

- Schreier, M. (2014). Qualitative content analysis. In U. Flick (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative data analysis. Sage.

- Science Innovation and Technology Committee. (2019). Impact of social media and screen-use on young people’s health. Retrieved 10/11/2023 from https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmsctech/822/82202.htm.

- Selwyn, N., & Aagaard, J. (2020). Banning mobile phones from classrooms—an opportunity to advance understandings of technology addiction, distraction and cyberbullying. British Journal of Educational Technology, 52(1), 8–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12943

- Smale, W. T., Hutcheson, R., & Russo, C. J. (2021). Cell phones, student rights, and school safety: Finding the right balance. Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy, 195, 49–64. https://doi.org/10.7202/1075672ar

- Supandi, Ariyanto, L, Kusumaningsih, W, & Aini, A. N. (2018). Mobile phone application for mathematics learning. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 983(1), 012106. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/983/1/012106

- Thomas, K. M., O’Bannon, B. W., & Britt, V. G. (2014). Standing in the schoolhouse door: Teacher perceptions of mobile phones in the classroom. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 46(4), 373–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2014.925686

- UK Government. (2019). English indices of deprivation 2019. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/english-indices-of-deprivation-2019.

- UNESCO. (2023). Global education monitoring report 2023: Technology in education—a tool on whose terms? Retrieved 17/01/2024 from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000385723.

- van der Mars, H. (1998). Observer reliability: Issues and procedures. In D. B. P.W. Darst & V. H. M. Zakrajsek (Eds.), Analyzing physical education and sport instruction (2nd edition, pp. 53–80) Human Kinetics Publications.

- Walker, R. (2013). “I don’t think I would be where I am right now”. Pupil perspectives on using mobile devices for learning. Research in Learning Technology, 21, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3402/rlt.v21i0.22116

- Wikström, P., Duek, S., Nilsberth, M., & Olin-Scheller, C. (2022). Smartphones in the Swedish upper-secondary classroom: A policy enactment perspective. Learning, Media and Technology, 49(2), 230–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2022.2124268

- Wood, G., Goodyear, V., Adab, P., Al-Janabi, H., Fenton, S., Jones, K., Michail, M., Morrison, B., Patterson, P., Sitch, A. J., Wade, M., & Pallan, M. (2023). Smartphones, social media and adolescent mental well-being: The impact of school policies restricting daytime use-protocol for a natural experimental observational study using mixed methods at secondary schools in England (SMART Schools Study). BMJ Open, 13(7), e075832. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2023-075832

- Yondr. (2023). How it works. Retrieved 22/01/2024 from https://www.overyondr.com/phone-locking-pouch.