Abstract

Introduction

Benzodiazepines have therapeutic indications, but their overuse may lead to misuse and dependence. Benzodiazepine dependence can be managed by health professionals, but stigma may result in individuals avoiding face-to-face help and turning to online resources. The internet is a popular, but unregulated resource and website quality are variable.

Aim(s)

(I) To systematically evaluate the quality of websites on benzodiazepine misuse and dependence using selected validated tools/variables. (II) To identify common themes presented on these websites.

Methods

Six search terms, “benzodiazepine treatment,” “benzo treatment,” “benzodiazepine addiction,” “benzo addiction,” “benzodiazepine help” and “benzo help,” were entered into two search engines. English-language websites were included if they presented information about benzodiazepine misuse and use disorder. Eligible websites were evaluated for quality of written information, readability, website usability, and other areas of interest such as advertising. Content was assessed by comparing themes covered in websites.

Results

Fifty-six websites were evaluated. Websites were generally good at providing balanced and unbiased information; however, treatment options were covered poorly. Most websites should be understood by individuals aged 15 years and older.

Discussion

The quality of websites varied, but common areas that require improvement include information on treatment options, effects on quality of life, and sources of information.

Conclusion

In general, the quality of websites presenting benzodiazepine information was mediocre based on our assessment. Future research could explore benzodiazepine users’ experiences of these websites as such studies may improve website quality.

Background

Benzodiazepines (BZDs) are a group of drugs that are prescribed to treat anxiety, insomnia, and seizures. They enhance the inhibitory neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) by acting on the GABA-A receptors in the brain, leading to anxiolytic, sedative, anticonvulsant, and muscle relaxant properties (Soyka Citation2017). Regular consumption of benzodiazepines may lead to sedative, hypnotic, or anxiolytic use disorder, and individuals may misuse them as a result (Soyka Citation2017). Data from the United States (US) in 2017 indicate that benzodiazepines and other tranquilizers were the third most misused prescription or illicit drugs (Votaw et al. Citation2019). Misuse, in this context, is broadly defined as any use of prescription medications without a prescription, at higher frequencies or doses than prescribed, or for their psychoactive effects instead of their medical indications (Votaw et al. Citation2019). Another study estimated that 2.2% of a nationally representative sample of adults in the United States self-reported misusing BZDs in the previous year, with “misuse without a prescription,” as the most common type of misuse; friends or family were the most common sources of BZDs in this study (Maust, Lin, and Blow Citation2019). In Europe, lifetime non-medical BZD use ranges from 1.7% in Germany to 6.5% in Spain (Hockenhull et al. Citation2021). In New Zealand, general practitioners have highlighted benzodiazepine misuse and dependence to be problematic in their practice (Sheridan and Butler Citation2011; Sheridan, Jones, and Aspden Citation2012) and updates for practitioners caution against large volume prescribing (BPAC Citation2021).

Benzodiazepine misuse and dependence is associated with morbidity and mortality, for example –psychiatric disorders, suicidal ideation and infectious diseases associated with injecting as well as overdose when used in combination with other central nervous system depressants (Votaw et al. Citation2019). While overdose from benzodiazepines alone is not typically fatal, the combination with alcohol or opioids can lead to synergistic depressant effects (Dowell, Haegerich, and Chou Citation2016), which may result in respiratory depression and death (Dasgupta et al. Citation2016; Jones, Paulozzi, and Mack Citation2014).

Benzodiazepine misuse and dependence is typically managed medically. Intervention may involve switching from a shorter to a longer acting benzodiazepine, followed by either gradual tapering until abstinence or a low maintenance dose is achieved, and/or psychological interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy (Soyka Citation2017; Brett and Murnion Citation2015). However, medical intervention may not be sought by all people who misuse drugs. Substance misuse and dependence is commonly associated with shame and stigma which may be barriers for those who want to seek treatment from medical professionals (Kennedy-Hendricks et al. Citation2017; Shupp et al. Citation2020). Thus, the internet can present as a popular, convenient, and more private source of information for people with substance misuse issues. The reliance solely on “health information” found on the internet may be problematic as online resources are unregulated, which may result in variable quality and accuracy of information. Research indicates that the average consumer may not have the health nor web literacy they need to evaluate the quality and reliability of information online (Battineni et al. Citation2020). This may result in negative health outcomes, since inaccuracies may lead to harm.

Similar studies have previously assessed the quality of web-based information for alcohol, cannabis and cocaine use and dependence (Khazaal et al. Citation2010; Khazaal et al. Citation2008a, Citation2008b). All three concluded that the quality of website information was either variable or poor.

To our knowledge, no published studies have been conducted on the quality of web-based BZD misuse and dependence information. This study aimed to examine the sources that would be found by people seeking this information.

Aim

This study aimed to (I) systematically evaluate the quality of websites providing information on benzodiazepine misuse and dependence and (II) categorize and quantify the presence of themes covered by the websites.

Methods

Study design

This study was a systematic, cross-sectional evaluation of websites on benzodiazepine misuse and dependence. In this study, we defined webpages as single documents on the internet (with individualized web addresses or links) and websites as collections of related webpages under the same identifying domain name.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included webpages/websites if they were published in the English language and presented information about benzodiazepine misuse, abuse, addiction, dependence, and/or withdrawal on the initial “landing” webpage.

We excluded webpages/websites if they required an access fee, were inaccessible (e.g., page/site link did not open to present the information suggested by search engine), required registration, or were not websites (e.g., they were PDFs of publications), or they were discussion forums.

Piloting

We conducted multiple piloting sessions, in which we searched for websites using the designated search terms, ensuring robust website selection criteria. We developed a data dictionary that defined the variables of interest and piloted the feasibility of the data collection process, identified any ambiguous definitions in the data dictionary, and recognized areas for improvement. Subsequently, clarifications made during this process ensured greater comprehension of the data extraction method which minimized errors and ensured that researchers were in complete agreement in interpreting the questions.

Identification and selection of potential websites and webpages

We used the two popular search engines Google and DuckDuckGo to identify potential websites. Google was selected as it is the most popular search engine worldwide; however, it does not offer private browsing (Pew Research Center Citation2012). Private browsing is important for stigmatized topics like drug misuse and dependence where anonymity may be preferred. Therefore, the private search engine DuckDuckGo was selected as it claims that it does not collect or share personal information which reassures users to search freely (https://duckduckgo.com/). At the time of undertaking the research, DuckDuckGo searches included results that would typically be found by Yahoo! and Bing which are the next most popular search engines worldwide after Google (Hollingsworth Citation2021).

The search terms “benzodiazepine treatment,” “benzo treatment,” “benzodiazepine addiction,” “benzo addiction,” “benzodiazepine help” and “benzo help” were run on each search engine. The term “benzo” was used because it is colloquially used by the public. Phrase searching with quotation marks was not used, to allow for broader search results and to imitate how the public might search. The first twenty results for each search term were collated (240 webpages in total). The search results included multiple webpages from the same website, so we consolidated webpages, keeping only one URL from each website to prevent overlap. Duplicate webpages were removed. We checked the webpages according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and where there were multiple webpages from the same website, they were consolidated into a single website for those webpages.

Data extraction

We explored website reliability, acceptability, quality of treatment information, conflict of interest, usability, advertising, online support services on websites and content themes. Accuracy of factual content was not assessed. Data were extracted between June and August 2020.

Reliability and quality of website information

We assessed website quality using the DISCERN tool. DISCERN is designed to enable both health information providers and consumers to appraise treatment choices for any health condition (Charnock et al. Citation1999). It comprises 16 questions that are used to assess the quality of written information. The questions are set on a scale from 1 to 5, representing a definitive “no” to a definitive “yes,” with additional ratings of 2, 3 or 4 given depending on the extent to which the webpages met the question’s criteria. Questions are split into three broad sections: The first section addresses webpage reliability, the second assesses the quality of information on treatment choices, and the third section allows for an overall webpage rating based on those in sections one and two. The tool has been widely used to evaluate a range of health-related websites (Grohol, Slimowicz, and Granda Citation2014; Jayasinghe et al. Citation2020; Kaicker et al. Citation2010).

Each webpage on a website was rated using DISCERN, and ratings for each DISCERN variable were averaged over webpages to obtain an overall rating for the website, rounded to the nearest whole number.

Conflict of interest and website usability

We assessed these parameters using some questions included in a validation instrument developed by Minervation to appraise healthcare websites (LIDA)—the Minervation validation instrument (Minervation Citation2007). This evaluates the design and content of health websites, gauging accessibility, usability, and reliability. Specific questions which were not considered to duplicate those in the DISCERN tool and relate to “conflict of interest” and “website usability” were chosen from the LIDA tool. Questions are rated based on how often the websites met the criteria from a scale “never,” “sometimes,” “mostly” and “always.”

Additional questions

We looked for the presence of the Health on the Net Foundation Code of Conduct (HONcode) logo. The HONcode is a certification system, assessing reliability and credibility of specific health information online. Websites may request HONcode logos, but the logo is only awarded if specified criteria are fulfilled; therefore, the presence of a HONcode logo on websites allows website users to be more assured of the trustworthiness of health information on the internet (https://www.hon.ch/HONcode/). The presence of a HONcode certification has been associated with website accuracy (Fallis and Frické Citation2002). Finally, we looked for the presence of any advertising and any specific recommendations for online support services such as web chat, helplines, contact forms, email, phone text messaging, discussion boards, personal contact numbers of therapists, or teletherapy linked to the website owner/publisher.

Readability

We used the Readable tool (https://www.webfx.com/tools/read-able/) to calculate the readability of the webpage. This website assessed readability using six indices which examined various aspects such as syllable count, average characters per word and sentence length and when combined, provided a final readability score (American grade level at which people could understand the information on the website). Higher grade levels indicate more difficulty in reading and comprehension. For health information websites, it is recommended to use readability of between 6 and 8 American grade levels (Daraz et al. Citation2011), which means that individuals aged 11–13 years old can easily understand the text.

Themes

We explored and categorized the content themes of websites to find out what sort of information website content creators include which indicates what they think their visitors will want or need. Themes were identified from a selection of clinical guidelines obtained through an internet search. These were then discussed, and final themes were agreed and defined. This provided a list of themes that might be expected to be on a website providing information about benzodiazepine misuse. The list of themes was piloted on the first few websites. All websites were then reviewed for the presence or absence of themes, and if any additional themes emerged, they were added to the list.

Data collection

Data collection was performed by researchers working in pairs for quality assurance. Data collection was undertaken independently by each member of the pair, and then differences between researchers were discussed and agreed by consensus.

Results

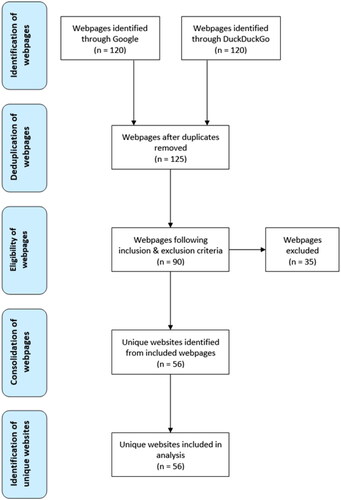

The initial searches using Google and DuckDuckGo identified 240 webpages. This reduced to 125 webpages after removing duplicates. We obtained a final dataset of 56 unique websites (see ). Forty-one websites (73.2%) were from the US, the remaining 13 (23.2%) were from other countries: United Kingdom (UK) (5), Australia (3), NZ (3), and Canada (2). The organizations which administered the websites were: government (2), university (1), not-for-profit (18), commercial (35) and unknown (1).

Reliability and quality of website information

Data from DISCERN analysis

Data from DISCERN ratings can be found in . All websites were rated using Section 1 of the DISCERN (Questions 1–8). Just over three-quarters (76.7%, 43/56) of websites were rated poorly (equal to or less than 2) on Question 1: “Are the aims clear?” (mean = 2.0, SD = 0.9). Most websites (n = 50) were considered relevant (scoring 4 or more in Question 3). The area which was rated the poorest was: “Does it refer to areas of uncertainty?” where only one website rated highly with a 5. All other areas in this section were rated a median of 3 (“sometimes”).

Table 1. Evaluation of benzodiazepine websites using the DISCERN Instrument Questions.

Section 2 (Questions 9–15) was only completed if the website contained information on treatment options (N = 50 websites). Overall, in this section, most websites rated below the midpoint of 3, indicating that the information on treatment options was inadequate. Particularly, websites tended to rate poorly on Question 13: “Does it describe how the treatment choices affect overall quality of life?,” and Question 15: “Does it provide support for shared decision-making?” The exceptions were Questions 12 and 14 which had mean ratings above 3. These questions relate to understanding the implications if no treatment was used and the possibility of more than one treatment choice.

For an overall rating of the websites (Question 16: “Based on the answers to all of the above questions, rate the overall quality of the publication as a source of information about treatment choices”), most of the websites rated 3 indicating that they had potentially important, but not serious, shortcomings. However, over two-fifths (42.8%) were rated as 1 or 2, revealing the poor quality of websites as sources of information about BZD dependence (“addiction”), misuse and relevant treatment choices.

Further analysis

Readability results

The mean readability grade score was 9.9 (SD = 1.7; Range from 7 to 20). The median grade level was 10. This indicates that most of the websites should be understood by individuals aged 15 years and older. Only four websites fell within the grade-recommended readability range of 11–13-year-olds (Grades 6–8).

Navigability, funding, HONcode

“Navigability” measures the relative convenience of finding information on websites (Wojdynski and Kalyanaraman Citation2016). Easy navigability, such as having clear sections, facilitates accessibility and the processing of information, whereas poor navigability can prolong searching time, causing users to repeatedly open the same webpages, or prevent users from searching further on the website (Wojdynski and Kalyanaraman Citation2016).

The websites were scored as “mostly” or “always” on navigability, structure and main block being readable. In over 85% of the websites, it was clear who owns the site and there was a declaration of the objectives of the people who run the site. However, disclosure of funding for the website was poor (see ).

Table 2. Evaluation of benzodiazepine websites using selected Lida questions.

Websites that meet the HONcode contain health information deemed high quality according to the HON foundation criteria. Only twenty websites (35.7%) were found to have the HONcode logo, over half (64.3%) did not. It is not clear if these websites have not applied for HONcode certification, or if it was not awarded due to the quality of information presented on the website. Statistical assessment found no correlation between HONcode certified websites and readability scores.

Advertising

Fourteen websites (25%) contained advertisements; five had advertising with content related to benzodiazepines, while three suggested the use of a particular drug/supplement that is intended to “cure,” “treat” or “relieve” symptoms. Most of the websites containing advertisements (n = 10) had intrusive advertising that interrupted the reading of content.

Online support

Most websites (n = 41; 73.2%) contained information on at least one online support service; the predominant services were helplines (n = 36; 85.7%) and contact forms (n = 28; 70%). Nine websites had other services, and these included discussion fora, mobile phone texting, discussion boards, personal contact numbers of different therapists, and teletherapy.

Theme analysis

Twenty-seven themes were identified in the websites (see ). “Descriptions/Indications of benzodiazepine,” “Brand/slang names for benzodiazepines,” “List of withdrawal symptoms,” “Health consequences of benzodiazepine misuse,” “Tapering as treatment option,” “Other non-pharmacological/psychological support” and “Concurrent drug abuse (e.g., opioids, alcohol)” were covered by more than three quarters of websites. “Follow-up” and “Complementary therapies/natural medications for withdrawal symptoms" were the least common themes.

Table 3. Themes present in benzodiazepine websites N = 56 websites.

Discussion

This systematic search for websites and subsequent data collection, assessment and analysis has found that the quality of web-based advice on benzodiazepine misuse and use disorder for the general public was of average quality, based on the overall DISCERN rating (Question 16). Most websites were rated as having moderate quality (mean = 2.6), indicating that they were useful sources of information about treatment choices, but with some deficiencies. Khazaal et al.’s combined study of web-based information addressing social phobia, bipolar disorder, pathological gambling, cannabis, cocaine and alcohol addiction reported similar findings in relation to website quality (Khazaal et al. Citation2009). Overall, websites in our study were considered balanced and unbiased. The average reading grade level was found to be higher than recommended by Daraz et al. (Citation2011).

Many websites did not have clear aims, meaning that consumers of these websites may not understand the purpose and objectives of the website, and therefore may find it difficult to initially see what information is contained or offered in its webpages. However, where websites clearly outlined their aims, those aims were generally well-covered by the content.

The clarity of information on the sources which had been used to compile or develop website content was inconsistent. Similar results have been found in other substance misuse-related studies: assessment of web-based information on cocaine addiction (Khazaal et al. Citation2008a) and alcohol dependence (Khazaal et al. Citation2010) found that only 42.1% and 41% of websites, respectively, detailed their sources’ references.

Most of the websites that were assessed by Section 2 of DISCERN (Questions 9–15) were considered to have limited information regarding benzodiazepine use treatment options. This is concerning because individuals with stigmatized conditions may use the internet for health information as opposed to seeking physical health care (Berger, Wagner, and Baker Citation2005), whilst others may wish to explore treatment options prior to engaging with a treatment provider.

Overall, most websites in our study were assessed as having excellent usability ratings meaning they had navigable, clear, and readable layouts. These findings are promising, as the convenient usability of websites can aid consumers in absorbing information quickly. Notably, benzodiazepine misuse is prevalent in older patients (Donoghue and Lader Citation2010). Therefore, improvements to website design are required to compensate for declining vision, cognition, and motor skills. This may be accomplished, for example, by optimizing usability and navigability, including clear and familiar methods for presenting information, and larger fonts to improve legibility (Becker Citation2004).

The presence of advertising was low across our sample of websites. However, of those websites that did contain advertising, less than half of advertising content was related to benzodiazepines and 21.4% recommended the use of a drug/supplement to “cure,” “treat” or “relieve” symptoms. Most websites had advertisements that interrupted the reading content, which could negatively affect users’ ability to process the information. It should be noted that websites recommending their own services were not included as advertising (only advertising by external providers was considered in this study).

Readability is a pertinent consideration of internet-based health information (Alamoudi and Hong Citation2015). The mean reading grade level of the websites in our study (9.91, approximate age = 15 years) was similar to other studies conducted involving websites addressing asthma and dysmenorrhea which scored 9.49 & 9.83, respectively (Banasiak and Meadows-Oliver Citation2017; Lovett et al. Citation2019). These means are higher than the recommended average reading in USA grade levels 6–8 for public health information (Daraz et al. Citation2011), indicating a potential negative impact on comprehension for the average reader.

Despite the websites being varied in their country of origin, there was considerable commonality between websites in terms of themes they included. Where themes were less commonly covered, many of these were of a more clinical nature, such as “Tapering schedules,” “Outpatient vs inpatient treatment” and “Follow up.” We note that the inclusion of tapering schedules was uncommon, and it could be argued that the inclusion of this might be important for anyone wishing to stop using BZDs alone. Conversely, as detoxification from benzodiazepines is not without risk, the inclusion of specific information on the risks of non-medical detoxification would also be of value.

This study has several strengths. It used a quasi-systematic review approach when identifying our sample; there were clear inclusion and exclusion criteria designed to clarify scope of our research and to select relevant websites. Two different search engines, Google and DuckDuckGo, were used to obtain a variety of potential websites. Piloting ensured robust methods. Despite the use of validated tools, subjective opinion was required to answer some questions, potentially introducing interpretation bias. To mitigate this, data collection was carried out by independently by two people, with data discussed by the pairs and then with the entire research team, to clarify any discrepancies in individual scoring.

This work is not without limitations. The accuracy of the information and content of the websites (such as pharmacological detail) is important as misinformation can also lead to harm. However, this was not evaluated as the researchers did not have the expertise to assess this. In addition, it was felt that data may be perceived differently by the research team compared to the general public; any future studies could use investigators from a range of backgrounds. The nature of the web means that information can be out of date. Websites do not always present any detail regarding when it was created or last updated. This means that people searching the web may be using outdated material. The results of the initial searches for websites were contingent on the geographical location and algorithm of an individual’s search. This effect is known as “personalisation”; 11.7% of Google searches show variation in results due to this effect (Hannak et al. Citation2013). Therefore, it is possible that our findings are not generalizable to other geographic locations. The search terms used were carefully selected, however the use of a wider range of terms may have yielded additional websites and data for analysis. The use of all drug terms including the plethora of worldwide drug brand names, along with generic drug names and known slang terms was considered to be overly complex, therefore the term “benzodiazepine” was selected alongside the truncated slang term “benzo.” As website content is dynamic and changes over time as it is updated, our findings are limited to that available/presented at the time of data collection. Another consideration is the comparability between our findings in relation to our evaluation of navigability. We generally found websites easy to use and acknowledge that this assessment was undertaken by undergraduate students who are familiar with searching for information on the internet. Future studies could use investigators from different backgrounds, such as people who use benzodiazepines and other health professionals, to mitigate this and compare their results to ours to identify any differences. The readability tests used may have been affected by the assessment content: long words such as “benzodiazepines” may have inflated reading grade scores, making websites seem harder to read. Furthermore, readability tools do not take account of visual aspects such as diagrams which can otherwise improve readability (Shedlosky-Shoemaker et al. Citation2009). Consequently, websites that contained non-textual media may have received artificially lower readability scores.

Conclusions

Our study found that websites that aim to provide public information on benzodiazepine misuse and dependence were of average quality. Important deficits, such as lack of transparency relating to information sources, reading age of information and poorly articulated website aims are an issue for substance misuse-related websites. Drug misuse and dependence are areas in which stigma and healthcare professional avoidance are common, therefore the importance of high-quality information available on the internet cannot be underestimated.

Acknowledgments

This research was undertaken as part of a Bachelor of Pharmacy Final Year Dissertation Project at the University of Auckland.

Disclosure statement

No conflicts of interest were reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Rhys Ponton

Rhys Ponton is a Senior Lecturer at the School of Pharmacy, University of Auckland. His research explores the use of controlled and illicit drugs, with a particular focus on harm reduction through the examination of the ways people prepare drugs for consumption.

Garion Gear

Garion Gear is a former student at the School of Pharmacy, University of Auckland, and graduated with a Bachelor of Pharmacy (Honours) degree.

Parsa Hadiyounzadeh

Parsa Hadiyounzadeh is a former student at the School of Pharmacy, University of Auckland, and graduated with a Bachelor of Pharmacy (Honours) degree.

Fyrooz Iqram

Fyrooz Iqram is a former student at the School of Pharmacy, University of Auckland, and graduated with a Bachelor of Pharmacy (Honours) degree.

Anes Kim

Anes Kim is a former student at the School of Pharmacy, University of Auckland, and graduated with a Bachelor of Pharmacy (Honours) degree.

Sophanna Out

Sophanna Out is a former student at the School of Pharmacy, University of Auckland, and graduated with a Bachelor of Pharmacy (Honours) degree.

Wey Ern Thoo

Wey Ern Thoo is a former student at the School of Pharmacy, University of Auckland, and graduated with a Bachelor of Pharmacy (Honours) degree.

Jane L. Sheridan

Janie L. Sheridan is a Professor of pharmacy at the University of Auckland. Her research broadly explores the use of illicit drugs and alcohol from a harm reduction perspective. She has a particular interest in community pharmacy harm reduction interventions, the use of alcohol by older people, and prescription drug misuse.

David Newcombe

David Newcombe is an Associate Professor in alcohol and drug studies and an associate director of the Centre for Addiction Research at the University of Auckland. His research explores ways of reducing the harms from alcohol and illicit drug use (cannabis and stimulants), and ways of managing FASD.

References

- Alamoudi, U., and P. Hong. 2015. Readability and quality assessment of websites related to microtia and aural atresia. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology 79 (2):151–156.

- Banasiak, N.C., and M. Meadows-Oliver. 2017. Evaluating asthma websites using the Brief DISCERN instrument. Journal of Asthma and Allergy 10: 191–196.

- Battineni, G., S. Baldoni, N. Chintalapudi, G. G. Sagaro, G. Pallotta, G. Nittari, F. Amenta, et al. 2020. Factors affecting the quality and reliability of online health information. Digital Health 6: 2055207620948996.

- Becker, S.A. 2004. A study of web usability for older adults seeking online health resources. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction 11 (4):387–406. doi:10.1145/1035575.1035578.

- Berger, M., T.H. Wagner, and L.C. Baker. 2005. Internet use and stigmatized illness. Social Science & Medicine 61 (8):1821–1827.

- BPAC. 2021. Benzodiazepines and zopiclone: Is overuse still an issue? https://bpac.org.nz/2021/docs/benzo-zopiclone.pdf.

- Brett, J., and B. Murnion. 2015. Management of benzodiazepine misuse and dependence. Australian Prescriber 38 (5):152–155.

- Charnock, D., S. Shepperd, G. Needham, and R. Gann. 1999. DISCERN: An instrument for judging the quality of written consumer health information on treatment choices. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 53 (2):105–111.

- Daraz, L., J. C. Macdermid, S. Wilkins, J. Gibson, and L. Shaw. 2011. The quality of websites addressing fibromyalgia: An assessment of quality and readability using standardised tools. BMJ Open 1 (1):e000152.

- Dasgupta, N., M. J. Funk, S. Proescholdbell, A. Hirsch, K. M. Ribisl, and S. Marshall. 2016. Cohort study of the impact of high-dose opioid analgesics on overdose mortality. Pain Medicine 17 (1):85–98.

- Donoghue, J., and M. Lader. 2010. Usage of benzodiazepines: A review. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice 14 (2):78–87.

- Dowell, D., T.M. Haegerich, and R. Chou. 2016. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. JAMA 315 (15):1624–1645.

- Fallis, D., and M. Frické. 2002. Indicators of accuracy of consumer health information on the Internet: A study of indicators relating to information for managing fever in children in the home. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 9 (1):73–79. doi:10.1136/jamia.2002.0090073.

- Grohol, J., J. Slimowicz, and R. Granda. 2014. The quality of mental health information commonly searched for on the internet. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking 17 (4):216–221.

- Hannak, A., P. Sapiezynski, A. M. Kakhki, B. Krishnamurthy, D. Lazer, A. Mislove, and C. Wilson. 2013. Measuring personalization of web search. WWW '13. Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on World Wide Web, Rio de Janeiro Brazil.

- Hockenhull, J., E. Amioka, J. C. Black, A. Forber, C. M. Haynes, D. M. Wood, R. C. Dart, et al. 2021. Non-medical use of benzodiazepines and GABA analogues in Europe. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 87 (4):1684–1694.

- Hollingsworth, S. 2021. DuckDuckGo vs. Google: An in-depth search engine comparison. https://www.searchenginejournal.com/google-vs-duckduckgo/301997/#close.

- Jayasinghe, R., S. Ranasinghe, U. Jayarajah, and S. Seneviratne. 2020. Quality of online information for the general public on COVID-19. Patient Education and Counseling 103 (12):2594–2597.

- Jones, C. M., L. J. Paulozzi, and K. A. Mack. 2014. Alcohol involvement in opioid pain reliever and benzodiazepine drug abuse-related emergency department visits and drug-related deaths – United States, 2010. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 63 (40):881–885.

- Kaicker, J., V. Borg D., W. Dang, N. Buckley, and L. Thabane. 2010. Assessment of the quality and variability of health information on chronic pain websites using the DISCERN instrument. BMC Medicine 8 (1):59.

- Kennedy-Hendricks, A., C. L. Barry, S. E. Gollust, M. E. Ensminger, M. S. Chisolm, and E. E. McGinty. 2017. Social stigma toward persons with prescription opioid use disorder: Associations with public support for punitive and public health-oriented policies. Psychiatric Services 68 (5):462–469.

- Khazaal, Y., A. Chatton, S. Cochand, O. Coquard, S. Fernandez, R. Khan, and D. Zullino. 2010. Quality of web-based information on alcohol dependence. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy 17 (3):248–260.

- Khazaal, Y., A. Chatton, S. Cochand, and D. Zullino. 2008a. Quality of web-based information on cocaine addiction. Patient Education and Counseling 72 (2):336–341.

- Khazaal, Y., A. Chatton, S. Cochand, and D. Zullino. 2008b. Quality of web-based information on cannabis addiction. Journal of Drug Education 38 (2):97–107.

- Khazaal, Y., A. Chatton, S. Cochand, O. Coquard, S. Fernandez, R. Khan, J. Billieux, et al. 2009. Brief DISCERN, six questions for the evaluation of evidence-based content of health-related websites. Patient Education and Counseling 77 (1):33–37.

- Lovett, J., C. Gordon, S. Patton, and C. X. Chen. 2019. Online information on dysmenorrhoea: An evaluation of readability, credibility, quality and usability. Journal of Clinical Nursing 28 (19–20):3590–3598.

- Maust, D.T., L.A. Lin, and F.C. Blow. 2019. Benzodiazepine use and misuse among adults in the United States. Psychiatric Services 70 (2):97–106. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201800321.

- Minervation. 2007. The LIDA Instrument Minervation validation instrument for health care web sites. Full Version (1.2) containing instructions. http://www.minervation.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Minervation-LIDA-instrument-v1-2.pdf.

- Pew Research Center. 2012. Search engine use. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2012/03/09/search-engine-use-2012-2/.

- Shedlosky-Shoemaker, R., A. C. Sturm, M. Saleem, and K. M. Kelly. 2009. Tools for assessing readability and quality of health-related web sites. Journal of Genetic Counseling 18 (1):49–59.

- Sheridan, J., and R. Butler. 2011. Prescription drug misuse in New Zealand: Challenges for primary health care professionals. Research in Social & Administrative Pharmacy 7 (3):281–293.

- Sheridan, J., S. Jones, and T. Aspden. 2012. Prescription drug misuse: Quantifying the experiences of New Zealand GPs. Journal of Primary Health Care 4 (2):106–112.

- Shupp, R., Scott L., M. Skidmore, B. Green, and D. Albrecht. 2020. Recognition and stigma of prescription drug abuse disorder: Personal and community determinants. BMC Public Health 20 (1):977. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-09063-z.

- Soyka, M. 2017. Treatment of benzodiazepine dependence. The New England Journal of Medicine 376 (12):1147–1157. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1611832.

- Votaw, V. R., R. Geyer, M. M. Rieselbach, and R. Kathryn McHugh. 2019. The epidemiology of benzodiazepine misuse: A systematic review. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 200: 95–114.

- Wojdynski, B.W., and S. Kalyanaraman. 2016. The three dimensions of website navigability: Explication and effects. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 67 (2):454–464. doi:10.1002/asi.23395.