ABSTRACT

With an increasing public interest in the roleplaying game ‘Dungeons & Dragons’ (D&D) comes the claim it holds psychological benefits. While the therapeutic roleplay is empirically well established, the evidence surrounding D&D is unclear. The current study aims to summarize the literature pertaining to this topic and present possible avenues for the implementation of D&D in psychological interventions. A Rapid Evidence Assessment (REA) was conducted following the standards by the Center for Evidence-Based Management. Relevant search strings were entered into seven databases (e.g., PsycArticles, PsycInfo, Child Development & Adolescent Studies). Only papers published in the English language till September 2020 were considered and their quality appraised. The thematic analysis of 13 studies yielded four themes: No unified personality type of D&D players, stakeholders’ attitude about D&D, lack of maladaptive coping associated with D&D, and potential psychological benefits of D&D. The results appear promising, but preliminary. Practical implications are contextualized with the wider literature.

Introduction

In the past 10 years, ‘Dungeons and Dragons’ (D&D), a fantasy roleplaying game (RPG), has emerged as a new way to conduct therapy (e.g., White, Citation2017), stay connected to family and peers in times of social isolation during COVID-19 (e.g., Consumber & Kjeldgaard, Citation2020; G. Hughes, Citation2021), and offers ways to support children and adolescents in their development (e.g., Zayas & Lewis, Citation1986). It even found its center in British society by being officially supported by the Scout Association, promising its young members new skills and confidence, as well as the Scouts Entertainer Activity Badge (Scouts, Citation2021). The game is led by a so-called Dungeon Master (DM) who guides the players through a narrative. Together with them, a collaborative storyline is created, which can be influenced by the players through their fantasy characters. At the most basic level, following the game rules involves pen-and-paper character sheets, dice, and the joint improvised roleplaying of all participants. The narratives span so-called campaigns that can go from weeks to years, with each session usually lasting several hours. While D&D has been first published in 1974 by Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson (Wizards of the Coast, Citation2003), it has seen a considerable rise in popularity from 2017 onwards (Pilon, Citation2019), with up to 15 million people playing 2017 in the US alone (Brodeur, Citation2018). As the community tries to rid itself of sexism, male gamer gatekeeping (Just, Citation2018; Schuller, Citation2016), old racist tropes (e.g., using reductive stereotypes of real-world ethnicities to portray fantasy races; Jarvis, Citation2020), and complicated rules to lower barriers at entry level (Carbonell, Citation2019), the audience becomes more diverse (Carbonell, Citation2019).

Due to the rapid spread of D&D as an interpersonal game event and the increased approachability of the game, mental health professionals are confident that the appeal across varying demographics can be utilized to unlock new avenues for intervention (e.g., D’Anastatasio, Citation2017). Institutions like the Bodhana Group in Canada (White, Citation2017) and campaigns like ‘Game to Grow’ (Game to Grow, Citation2020) already use D&D to support individuals in a therapeutic context. Some even offer training for counselors and therapists, but a manualized approach has not been published at the time of this article. Nevertheless, the opportunity to move therapeutic interventions online in a structured manner has been utilized by many, for example, by Eisenman and Bernstein (Citation2021) for group therapy and by Spotorno et al. (Citation2020) for primary school children. Anecdotal evidence suggests that RPGs can decrease impulsivity and boundary issues, without players – in this case students between eleven and 13-years old (Enfield, Citation2007) – necessarily acknowledging the behaviors they need to modify. However, the initial reception of the game was not all positive: At minimum, the media framed D&D as escapism to the extent that individuals would forget how to cope with reality (e.g., Bowman, Citation2007); at maximum, media and scholars viewed links between D&D and deviance, such as criminality and Satanism (e.g., Leeds, Citation1995). Most of these claims were later refuted by the media and/or scholars who failed to produce scientific evidence supporting these ideas (e.g., Adams, Citation2013). Instead, scholars offered the first promising insight into the utility of D&D in therapy, for example, benefitting patients with psychosis (Blackmon, Citation1994) or supporting individuals with depression (J. Hughes, Citation1988). Broader reviews, for example, by Bratton and Ray (Citation2000), who reviewed 82 play-therapy studies, suggest that this specific delivery format could effectively teach children about self-concept, social skills, and anxiety management, resulting in considerable behavioral changes. These findings were replicated with a meta-analysis by Kipper and Ritchie (Citation2003).

Roleplaying in Therapeutic Settings

While research on the effects of games in therapeutic interventions appears to be in its infancy (Adams, Citation2013), the reviews by Bratton and Ray (Citation2000) and Kipper and Ritchie (Citation2003) show a wide breadth of knowledge regarding therapeutic roleplaying. The approach has been defined to create an imaginary reality (Moreno, Citation1978) and is a type of experiential technique that involves a reenactment of real or imaginary situations from a person’s past, present or the future (Keulen-de Vos et al., Citation2017, p. 80). As such, it is commonly used to improve a person’s ability to understand emotions, and how they are related to current triggers (Rafaeli et al., Citation2011) or to model ideal behaviors and practicing skills in a safe environment (Matthews et al., Citation2014).

A safe environment for the exploration of hypothetical scenarios is only one of the many empirically supported benefits. Roleplay has been found to facilitate attitudinal change more effectively than psychoeducation (Elms, Citation1967), as well as increasing self-esteem and relational attitudes (Gorman et al., Citation1990). Roleplay has been found to be a useful technique for adolescents whose personality and identity formation is developing (Carnes & Minds on fire, Citation2014), increasing self-awareness and empathy (Meriläinen, Citation2012), as well as critical and ethical reasoning (Simkins, Citation2010). Engagement in roleplaying video games has also been found to improve spatial reasoning (Feng et al., Citation2007) and help establish new friendships and practicing social skills (Billieux et al., Citation2011; Dupuis & Ramsey, Citation2011). These benefits seem to appear consistently across different therapy modules, including varying theoretical backdrops (Matthews et al., Citation2014). In particular, in combination with several therapy modules, roleplaying is discussed to increase positive effects (Keulen-de Vos et al., Citation2017). The authors propose that the use of roleplay and drama therapy can act more effectively and quickly than verbal psychotherapies alone.

Furthermore, these advantages appear especially valid for younger and/or vulnerable individuals, including clients who struggle to engage verbally in therapy as it attends to experiential learning (Matthews et al., Citation2014), clients with intellectual disabilities to improve creativity and cognitive problem-solving (Zayas & Lewis, Citation1986), and adolescents with delayed interpersonal skills (Rosselet & Stauffer, Citation2013). Other groups that have been investigated in this context were patients with a personality disorder, highlighting that mainly individuals with an emotionally detached or avoidant personality style benefitted the most from roleplaying (Keulen-de Vos et al., Citation2017). Muñoz et al. (Citation2012) previously explored similar improvements in communication and identification of facial expressions in a group of autistic clients, mirroring findings by Ramdoss et al. (Citation2012) who found better reading and writing skills using video games.

However, research also suggests that some types of clients are struggling to benefit from roleplaying interventions. For example, Brummel et al. (Citation2010) note that for some participants, roleplay can make them feel awkward and uncomfortable. Werth (Citation2018) explored the effectiveness of roleplay for students learning Chinese in US-American classes and found that for such approaches to be effective, participants must have the ability to trust, work collaboratively, and have rapport with the person facilitating the roleplay. Qualities such as being shy, reserved, lacking in confidence, or viewing roleplaying as childish were all found to be barriers to engagement. Instead, Werth (Citation2018) showed that believing in the efficacy of roleplay as a technique was crucial for improving skills development and participation. The role of attitudes was also viewed as crucial by LeBaron and Alexander (Citation2009) who identified that engagement in roleplay may be influenced by cultural preferences. They noted that generally some cultural groups are uncomfortable with pretending to impersonate others. Mittelmeier et al. (Citation2015) also found that the cultural traits of individualism and uncertainty avoidance (rather than personality) predicted engagement in group work participation.

One way to encourage clients to participate and breach those barriers is via gaming rewards. For example, Worth and Book (Citation2015) found that although people who scored low on extraversion did not like playing social aspects of roleplay video games, they could be motivated to engage in more social aspects of the game which require multi-player cooperation between large groups of players (e.g., raids) through high in-game rewards such as receiving artifacts that benefit their gameplay or improving their reputation in the game. Furthermore, the authors hypothesized that these incentives can be used strategically to shape the client’s behavior. In their study, respondents who scored high on the Player-versus-Player scale (i.e., make-belief combat with other players) using the In-Game Behavior Questionnaire, were also associated with typical personality characteristics associated with psychopathy, such as dishonesty, recklessness, and impatience (Worth & Book, Citation2015). However, through a reward system favoring alternative behavior (e.g., compassion, kindness), it might be possible to shift behavioral preferences.

Although the benefits of roleplaying in therapy have been established, research has shown that therapists sometimes struggle to deliver modules of this type due to therapist drift, i.e., non-adherence to evidence-based treatment (Waller, Citation2009). Trivasse et al. (Citation2020) identified several factors which may contribute to this including: lack of training, knowledge, and confidence; anxiety and negative beliefs about the therapy technique. Therapists that dislike roleplays in their work appear to often feel withdrawn, reserved, and/or uncomfortable with self-disclosure and often seemed to prefer a rigid division between themselves and their clients (i.e., they did not like the events in the roleplaying session to trigger their own associations, emotions, or memories; Hollander & Craig, Citation2013). In order to overcome these barriers, Beidas and Kendall (Citation2010) suggest that therapist training should not only focus on increasing knowledge and confidence in roleplaying but should also address specific contextual variables such as those specific to the organization in which therapy is being provided and the characteristics of the therapist and the patient. Specifically, this should include the use of roleplays and modeling (i.e., demonstrating skills to a supervisee; Edmunds et al., Citation2013). Lastly, therapists need to be made aware of the risk of negative countertransference (Pithers, Citation1997). In other words, roleplaying can expose traumatic events of a client, which in turn can trigger experiences in the therapist like post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms, burnout, and/or compassion fatigue (Deighton et al., Citation2007).

These considerations are linked to reflections about the risks that could be associated with therapeutic roleplaying. While it appears that benefits prevail for especially vulnerable client categories (as mentioned above), the implementation must be done with great care, as emphasized by Meyer et al. (Citation2019). The authors found that participants could overly immerse themselves in different perspectives, which changed the clients’ self-sense, especially when those clients had no firm grasp of their own identity. This mirrors effects from the wider literature on make-belief and acting (e.g., Seton, Citation2008). The authors discussed how actors may experience long term negative effects from taking on the role of certain characters due to immersion, referred to this as ‘post-dramatic stress’ (Seton, Citation2008, p. 1) which mirrors some of the trauma responses seen in people with post-traumatic stress disorders such as involuntary reexperiencing, dissociation and hyper-arousal. Research exploring brain activity related to this behavior shows that acting is associated with the deactivation in the front and midline of the brain, which is associated with thinking about the self (Brown et al., Citation2019). Even assuming a different accent of another or mimicking a gesture of another had similar effects. Beyond potentially adverse shifts in thinking about themselves, roleplaying can also overwhelm individuals who present with an over-controlled personality style (Davey et al., Citation2005; Keulen-de Vos et al., Citation2017; Testoni et al., Citation2020). As such, alternative coping styles should be taught prior to roleplaying sessions (e.g., Davey et al., Citation2005) or individual trauma therapy offered to clients with active trauma (Hollander & Craig, Citation2013) to prepare for roleplaying interventions.

Overall, it has become apparent that the literature pertaining to therapeutic roleplaying is diverse and varied. Several mechanisms on how this interventional approach impacts clients are discussed. According to Bowman and Lieberoth (Citation2018) brain imaging studies show significant overlap between the neural networks used to understand stories and those used in social interaction (i.e., the theory of mind or mirroring; Mar, Citation2011). Theory of Mind (ToM) refers to the ability to infer mental states to self and others (Premack & Woodruff, Citation1978). In addition, ‘mirroring’ refers to the way in which neurons are activated in humans merely by observing another engage in a behavior. For example, if a person sees someone else being hit on the leg, they may respond unconsciously by their own leg twitching or flinching. It is assumed that through these activations roleplay can lead to increases in empathy, understanding, and taking on the perspectives of others (Kaufman & Libby, Citation2012; Mar et al., Citation2009). Meanwhile, developmental psychology frames pretend play as a form of adaptation which facilitates survival skills (Steen & Owens, Citation2001), as well as social identities (Stenros, Citation2015). Segal (2018)summarizes this in three functions: (1) physically and mentally participating in somebody else’s actions; (2) understanding another person’s experience; and (3) regulate their own emotions. In a fictional context, Lankoski and Järvelä (Citation2012) describe this phenomenon as immersion (e.g., feeling embarrassed when watching a person do something embarrassing on the TV), which is represented in neuronal activation like the real-life experience of such events (Lieberoth, Citation2013). While usually individuals understand on a cognitive level the difference between immersion and real experiences, this can be compromised in individuals with dissociation (Lieberoth, Citation2013). Abraham et al. (Citation2009) also showed the impact on individuals who did not dissociate, but for whom the roleplay scenario was heavily relevant on a personal level, resulting in a blurring between fantasy and reality.

Research aims

As highlighted before, the literature regarding the therapeutic utility and effectiveness of D&D is unclear because evidence is mainly anecdotal, but appears promising through its closeness to supportive empirical evidence in the wider realm of roleplaying therapy. Furthermore, a structured overview of the empirical evidence pertaining to the therapeutic benefits of D&D does not currently exist. Hence, the current study aims to utilize a rapid evidence assessment (REA) to explore the empirical findings in the literature pertaining to the utility of D&D in psychological interventions. The REA’s methodology is presented, followed by the findings of the current review. Concluding remarks will provide further contextualization and outline future research.

Methodology

A REA was conducted following the standards by the Center for Evidence-Based Management (CEBMa; Barends et al., Citation2017). A REA is like a systematic review in that it is a method used to identify all relevant studies on a specific topic as comprehensibly as possible using a systematic approach based on explicit inclusion and exclusion criteria. The benefit of this approach is that it is transparent, verifiable, and reproducible (Barends et al., Citation2017). A REA adopts the same methodology as a systematic review in that it follows a 12-stage process. While this methodology is a part of the systematic approaches, it makes concessions. Here, no additional assessors and no gray literature (e.g., unpublished articles, etc.) were considered to allow for the rapid initial exploration of an understudied area.

Data search

The inclusion criteria for the literature search were as follows: (1) The studies had to address the utility of D&D, ideally in a therapeutic context, and (2) they had to present empirical evidence. Papers were excluded, if they presented exclusively qualitative data, did not utilize D&D in their study design, or focused on non-psychological topics (e.g., the sociology of gaming, legal discourses, or biological changes). Hence, the following search string was used: “Dungeons & Dragons” NOT “legal” OR “eco*” OR “medicine” OR “media” OR “anthropology” OR “ethic*” OR “culture*,” utilizing the following databases: PsycArticles, PsycInfo, Child Development & Adolescent Studies, Educational Administration abstracts ERIC, Social Sciences, SocINDEX, and GoogleScholar. Only papers published in English language until September 2020 were considered.

Quality appraisal

Following the guidelines by Barends et al. (Citation2017) the screening of papers was established following a two-fold approach. First, all included studies were classified based on the six levels of appropriateness (Petticrew & Roberts, Citation2008; Shadish et al., Citation2002) that assess a study’s validity. Levels range from “AA,” representing the so-called “gold standard” (Barends et al., Citation2017, p. 17) with systematic reviews or meta-analyses of randomized control trials, to the lowest level of appropriateness “E,” representing case studies, case reports, and other anecdotal data. Secondly, methodological quality was assessed using the Cohort Study Checklist by the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, Citation2018). The 12-item tool guides the assessor systematically through the appraisal, enabling critical reflection of each study’s results. Items include the appraisal of the research question and the recruitment process, among other aspects. Depending on the tally of methodological weaknesses, the appraised studies were downgraded a certain number of levels (e.g., two weaknesses result in the downgrading of one level, three in two levels, etc.; Barends et al., Citation2017).

Thematic analysis

To summarize the studies’ findings, a thematic analysis was conducted, following Braun and Clarke (Citation2006) guidelines. These steps comprised (1) becoming familiar with the studies; (2) allocating initial codes; (3) searching for overarching themes; (4) reviewing themes; (5) defining and naming themes; (6) summarizing the analysis’ findings in a written report.

Results

Literature search

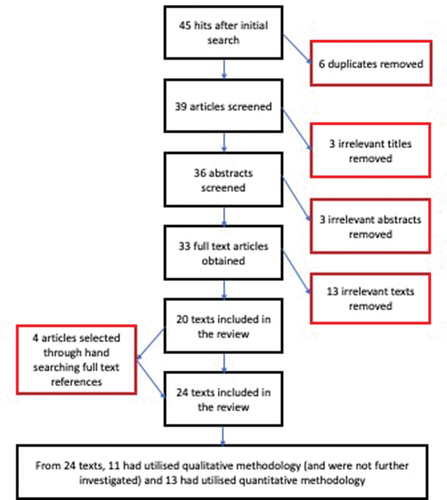

Initially, the search yielded 45 articles. With six duplicates removed, the title review resulted in 36 publications. Further, three studies were removed, based on their abstracts, and 13 more, based on the texts. With four articles added by searching the full texts references, a total of 24 texts were included in the final review. Of those, eleven had utilized qualitative methodology and thirteen had utilized quantitative methodology ()

Characteristics of included studies

From the 13 finale studies, one reached the quality level “A,” six reached the quality level “B” and another six reached the quality level “D” (). All studies showed no weaknesses or only one methodological flaw, with most utilizing either a non-randomized control study design or a cross-sectional survey. Seven articles were published before 2000, while additional six were published after 2010. The 13 studies included 992 participants, with 253 female and 422 male participants; several studies did not report the participants’ gender. Three studies attended to ethnicity noting 134 participants were classified as white. Two studies included participants who classed themselves as either Black (N = 7), Hispanic (N = 13) or Asian (N = 2). None of the studies reflected on sexuality.

Table 1. Study characteristics of all reviewed English publications utilizing quantitative methodology.

Themes

The thematic analysis of the 13 studies yielded four overarching themes: No unified personality type of D&D players, stakeholders’ attitude about D&D, lack of maladaptive coping associated with D&D, and potential psychological benefits of D&D.

No Unified Personality Type of D&D Players. Eight articles have explored whether a particular type of player is attracted to D&D. The six could not find a unifying profile that would distinguish the D&D community from the public. Carter and Lester (Citation1998) found no difference to a non-player control group on the Eysenck Personality Inventory (Eysenck & Eysenck, Citation1964). Abyeta and Forest (Citation1991) found slight elevations regarding psychoticism (associated with egocentric behavior, aggression, and assertiveness, among others), but overall personality profiles on the same instrument appeared comparable to control groups. Similarly, Simon (Citation1987) found no different personality type when comparing new to established D&D players on the 16 Personality Factor Questionnaire (Cattell et al., Citation1970). Carroll and Carolin (Citation1989) used the same instrument comparing players to a non-player control group, with no significant differences reported. Rosenthal et al. (Citation1998) focused on neuroticism as a personality trait, measured with the 25-item Revised Willoughby Schedule measuring neuroticism (Willoughby, Citation1932). The authors compared D&D players to a convenient sample of male national guardsmen, who had a comparable number of friends. No clinically relevant differences regarding neuroticism were found (Rosenthal et al., Citation1998). Chung (Citation2013) found slight elevations on the openness scale, when utilizing the Big Five Inventory (John & Srivastava, Citation1999) with players and non-players; the construct generally reflects readiness to accept or engage in new experiences or situations (John & Srivastava, Citation1999).

Douse and McManus (Citation1993) were one of the only authors presenting meaningful differences between D&D players and a control group. They found that players were less feminine and less androgynous than the norms included in the Bem Sex-Role Inventory (Bem, Citation1981). The authors concluded that this would make players more introvert and less empathetic (Douse & McManus, Citation1993). Regarding introversion, similar findings were reported by Wilson (Citation2007). Additionally, the author found that D&D players’ information gathering process appeared to differ, being more intuitive and perceptive. Both attributes were measured with the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (Myers, Citation1962), framing D&D players in Wilson’s study (Wilson, Citation2007) as more comfortable varying possibilities and relying more on introspection in decision-making than the norm.

Stakeholders’ attitude about D&D

Two articles investigated the attitude of service providers who would consider D&D in their interventions. Professions included social workers (Ben-Ezra et al., Citation2018) and psychiatrists (Lis et al., Citation2015). While some social workers (45 out of 130) appeared to view RPGs like D&D contributing to psychopathology, this relationship was influenced by the participants’ knowledge about that game (Ben-Ezra et al., Citation2018). However, even those individuals viewing RPGs as potentially contributing to mental health problems were not opposed to learn more about games such as D&D. The rate of negative judgment toward D&D was lower than in a previous study by Lis et al. (Citation2015), where 22% of the psychiatrists perceived a link between D&D and psychopathology. In this sample, 6% played D&D themselves, likely contributing to the overall positive appraisal of the game.

Lack of maladaptive coping associated with D&D

Three studies have explored negative aspects that could be linked to playing D&D: criminality (Abyeta & Forest, Citation1991), depression, including suicidal ideation (Carter & Lester, Citation1998), alienation, reclusiveness, and perceiving one's own life as meaningless (DeRenard & Kline, Citation1990). Abyeta and Forest (Citation1991) found no significant link between the game and self-reported criminality, when players were compared to a non-playing control group. Instead, the authors found lower levels of psychoticism. Measured by the Eysenck Personality Inventory, the personality pattern describes individuals that are generally more withdrawn, are perceived as hostile or lacking sympathy (Eysenck & Eysenck, Citation1964). Not only was psychoticism found in higher levels in the non-player sample, where it could also be linked to the occurrence of criminality, but D&D players exhibited even inverse ratings on the psychoticism scale (Abyeta & Forest, Citation1991). Similarly, Carter and Lester (Citation1998) found no meaningful differences between D&D players and a sample of undergraduate students at the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck et al., Citation1961), which measures depression severity and suicidal ideation. However, DeRenard and Kline (Citation1990) found higher rates of players feeling alienated and not interested in mainstream media, when compared to a control sample. But this did not translate to more players feeling that their lives were meaningless, as hypothesized. In fact, the authors observed that the opposite was true, with individuals in the control sample expressing more meaningless, while the inverse seemed true for D&D players.

Potential psychological benefits of D&D

Four studies have investigated how D&D could benefit players’ psychology. Chung (Citation2013) compared D&D players’ creativity with non-players using the Wallach–Kogan Creativity Tests (i.e., a divergent thinking test; Wallach & Kogan, Citation1965) and several experimental priming conditions. Chung (Citation2013) observed that participants with RPG experience generally showed higher levels of creativity than other participants. This was mainly in the domains of originality and uniqueness of the responses, as opposed to flexibility and fluency of thinking. Rivers et al. (Citation2016) also explored thinking styles, namely empathy (i.e., understanding others and relating to their feelings on an emotional level). As a result, the authors compared RPG players, including D&D players, to norms using the Davis Interpersonal Reactivity Index (Davis, Citation1994). Beyond this empathy measurement, the Tellegen Absorption Scale (Tellegen, Citation1982) was utilized to assess the extent to which participants can immerse themselves in an activity. Rivers et al. (Citation2016) hypothesized that high levels of absorption could facilitate greater levels of empathy not just with other people, but also with fictional characters. Results indicated higher levels of both variables in the RPG player sample compared to norms, with a significant correlation between empathy and absorption. Both creativity, and empathy (in the form of maintaining friendships), were important reasons to join D&D groups in a previous survey conducted by Wilson (Citation2007) with D&D players. Other motivators included: Expression of alter egos; personal growth regarding the meaning of life; and increased strategic thinking. Furthermore, Wilson (Citation2007) showed a significant link between these reasons and self-reported spirituality, measured with the Spiritual Perspective Scale (Reed, Citation1986).

While all these studies were correlational, Wright et al. (Citation2020) conducted a non-randomized control study with two time points to assess causality regarding D&D and its potential benefits. The authors explored how the game could facilitate moral development. Hence, the assigned students into player and non-player groups, with the player groups also partially consisting of already experienced D&D players. Their moral judgment was measured with the structured Defining Issues Test and the Self-Understanding Interview (Bebeau & Thoma, Citation2003), while being confronted with varying moral dilemmas. The times of measurement were before and after six 4-h sessions of D&D (or in the case of the control group after a period with no intervention). The authors noted a significant change in moral reasoning toward expressing personal interests while maintaining relationships and a focus on maintaining established norms, with significant differences between player and non-player groups. Wright et al. (Citation2020) concluded that D&D benefitted the moral development, especially the expression, and maintenance of social interests.

Conclusion

This is the first study to offer a systematic overview of the current empirical evidence regarding the therapeutic utility of D&D. The analysis of 13 articles yielded four overarching themes: No unified personality type of D&D players, stakeholders’ attitude about D&D, lack of maladaptive coping associated with D&D, and potential psychological benefits of D&D. It appears that the research basis is limited, with mostly low-level quality studies available. Nevertheless, some of the studies’ findings map onto the wider therapeutic roleplaying literature.

That is, stakeholder’s attitude about D&D and potential psychological benefits of D&D seem to replicate the general findings. The current review found that professionals do appear reluctant at times to use D&D as a therapeutic intervention. This attitude was influenced by their level of unfamiliarity with the game (e.g., Ben-Ezra et al., Citation2018). This reflects the most recent results by Trivasse et al. (Citation2020) who found that the implementation of therapeutic role playing is often hindered by therapist’s lack of knowledge, making specific training necessary. It is assumed that deepening our understanding and building confidence could also benefit the application of therapeutic D&D games, as well as developing an organizational culture that supports such implementations, as discussed by Beidas and Kendall (Citation2010), when reflecting on general roleplaying approaches. However, it could also be hypothesized that the investigated stakeholders in the reviewed studies were more reluctant to utilize D&D as a therapy format, because it is less well established and less substantiated than other roleplaying formats.

This links to the second theme, potential benefits of D&D, which summarizes tentative evidence on how the game can support clients. It appears that D&D facilitates higher levels of creativity (e.g., Chung, Citation2013) and empathy (e.g., Rivers et al., Citation2016). This was linked to a variety of other factors, for example, maintaining friendships and general feelings of connectedness, exploring varying lifestyle models (e.g., Wilson, Citation2007), as well as a heightened ability to consider group’s needs and more balanced differential moral reasoning (Wright et al., Citation2020). As such, the findings are reminiscent of the wider roleplaying literature, where positive effects can be observed, such as increased self-awareness, empathy (Meriläinen, Citation2012) and improved ethical reasoning (Simkins, Citation2010), especially among adolescents (Carnes & Minds on fire, Citation2014).

Rivers et al. (Citation2016) discussed that a driving factor could be the high levels of immersion they found among D&D players. Similarly, psychological mechanisms are also mentioned by Lieberoth (Citation2013), when reflecting on therapeutic roleplaying. However, the author also emphasizes that this could present with a risk, especially for individuals who tend to dissociate. Notably, in the D&D literature, the notion of risk is not represented in a similarly varied manner as in the general debate. In fact, it appears simplistic, when reviewing the theme lack of maladaptive coping associated with D&D. It appears that especially in older studies the predominant assumption among researchers was that D&D must be associated with socially unacceptable and/or stigmatized behaviors, such as criminality (Abyeta & Forest, Citation1991) or suicidal ideations (e.g., Carter & Lester, Citation1998). This was likely reflective of the initial reception of the game, framing it as Satanism (Leeds, Citation1995) or detachment from reality (Bowman, Citation2007). None of the reviewed studies could find any meaningful differences between the compared groups that would indicate that D&D was utilized as a maladaptive coping attempt. The only significant results by DeRenard and Kline (Citation1990) hinted toward feelings of alienation and disinterest regarding mainstream culture that was common among D&D players.

Similarly, some of the studies included under the theme no unified personality type of D&D players sought out to find incriminating evidence that would discount D&D. For example, Rosenthal et al. (Citation1998) unsuccessfully attempted to portray D&D players as more neurotic and withdrawn than a control group that was matched regarding the number of friends. At the same time, Douse and McManus (Citation1993) concluded that significant differences between D&D players and norms associated with stereotypically female and male behavior would indicate that players are more introvert and less empathetic. However, most studies subsumed in this theme did not find any significant differences between D&D players and the public. As with previous themes, the contrast in perspective to the general roleplaying literature is stark. The latter focuses more on what types of individuals either benefit from roleplaying (e.g., Ramdoss et al., Citation2012) or who would require specific safeguarding (e.g., Brummel et al., Citation2010). The D&D literature is falling short to reflect on any of these considerations, likely because the research in this area is still in its infancy (Adams, Citation2013).

Practical implications

Despite the limited insight, a closeness to the wider roleplaying literature could be demonstrated. Hence, it appears justified to derive several practical implications for the utilization of D&D in the context of therapy from that body of research:

Clinicians should be suitably trained and appropriately supported by their organization if they want to implement D&D in their therapeutic efforts.

Clients should be appropriately prepared. As the therapeutic roleplaying literature suggests, the isolated use of roleplaying interventions can be risky, in case it confronts the client with previously unaddressed trauma (e.g., Meyer et al., Citation2019).

Linked to this D&D is likely more beneficial, if used in conjunction with other therapeutic modules, as the wider literature suggest that roleplaying can heighten and intensify therapy benefits (Keulen-de Vos et al., Citation2017).

The use of D&D for therapeutic purposes should be specific and outcome oriented. This suggestion serves a two-fold purpose: First, it appears that roleplaying is best supported to aid modeling and practicing new behavior (e.g., Matthews et al., Citation2014). Hence, it is fair to assume that D&D can support similar efforts while potentially being ineffective for more holistic and therefore unspecific goals (e.g., to alleviate general trauma symptomatology, instead of specific maladaptive coping). Second, the general literature emphasizes that for some types of clients roleplaying can come with an increased risk of detrimental side effects (e.g., Deighton et al., Citation2007). Therefore, great care must go into the justification and planning of D&D-focused interventions.

Nevertheless, roleplaying has been demonstrated to have many positive effects, especially for adolescent clients and other vulnerable clients (e.g., Carnes & Minds on fire, Citation2014). As such, D&D can help foster an interest in clients that might even be reluctant to participate in therapy and can facilitate change without the clients necessarily needing to acknowledge the addressed behavior (e.g., Enfield, Citation2007).

Limitation

These suggestions are merely preliminary, given the study’s limitations. These include an exclusive focus on articles published in the English language, hence, ignoring any other empirical evidence. However, the potential additional studies will be limited in their numbers, given that D&D and its rules are only published in English. Furthermore, the study did not consider adjacent topics such as roleplaying in video games or the quality of empirical evidence generally related to roleplaying. The latter was addressed elsewhere, for example, by Kipper and Ritchie (Citation2003) in their exhaustive meta-analysis. Given the variety of approaches, it was important to solely focus on the D&D application to therapy. Lastly, the utilization of the REA methodology, as opposed to a full systematic literature review, is limiting the current study’s reliability. However, given the explorative nature of this review, it is considered appropriate to employ a REA with only one assessor appraising the literature and its quality.

Besides the limitations of the review itself, the findings are also further limited in their generalizability given the included studies’ shortcomings. For example, only one study utilized a pre- and post-measurement design (Wright et al., Citation2020), allowing for causal conclusions. This is likely because D&D requires a considerable amount of familiarity with the rules and a long-lasting commitment between players and the DM. As a result, more studies tend to observe already existing groups. Lastly, most publications (N = 7) have been published before 2000, with several being more than 30 years old. Hence, it appears that several studies base their findings on often outdated or inappropriate research instruments. This is likely reflective of the initial notion that D&D was linked to ostracized behavior, skewing the findings. Linked to this is the fact that study participants seemed to be mostly male and white, not reflecting recent changes in the player population outlined previously (e.g., Jarvis, Citation2020; Just, Citation2018). The outdated data is not racially inclusive and does not represent the growing number of women in the community, likely limiting the generalizability of the findings and emphasizing the need for future research.

Future research

Throughout the review, it becomes apparent that more research was needed to conclusively present evidence supporting or negating the use of D&D in a therapeutic context. The initial findings appear promising, especially in their closeness to the wider roleplaying literature. However, further research is needed to address the previously outlined shortcomings. It is likely that the observational approach remains the most feasible study design to explore the effects of D&D (due to the time constraints and extended knowledge necessary to participate in such games). However, future studies can utilize current and validated research instruments, incorporate multiple time points in their investigations, and match D&D players on several characteristics (e.g., age, gender, ethnicity) with non-players representing a control group. Through this, further avenue of application can be explored. Development of structured narratives specific to the therapy outcomes that are aimed to be achieved must include (i.e., specific modules for social skills, empathy, moral reasoning, etc.), as well as validating these and linking them to training for clinicians in the field. Finally, anecdotal reports regarding the social connectivity that the game allows even during COVID-19 (Eisenman & Bernstein, Citation2021; Spotorno et al., Citation2020), hint toward great opportunities and need to be explored further. It is hoped that through those steps D&D can provide practitioners with a new, engaging, and multi-purposed tool in their toolbox to support especially more vulnerable clients in practicing and expanding skills gained in therapy.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abraham, A., Von Cramon, D. Y., & García, A. V. (2009). Reality= relevance? Insights from spontaneous modulations of the brain’s default network when telling apart reality from fiction. PloS One, 4(3), e4741. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0004741

- Abyeta, S., & Forest, J. Relationship of role-playing games to self-reported criminal behaviour. (1991). Psychological Reports, 69(3), 1187–1192. 10.2466%2Fpr0.1991.69.3f.1187. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1991.69.3f.1187

- Adams, A. S. (2013). Needs met through roleplaying games: A fantasy theme analysis of dungeons & dragons. Kaleidoscope: A Graduate Journal of Qualitative Communication Research, 12(1), 69–86.

- Barends, E., Rousseau, D. M., & Briner, R. B.(Eds.). (2017). CEBMa guideline for rapid evidence assessments in management and organizations (version 1.0).Center for Evidence Based Management, Amsterdam. https://www.cebma.org/wp-content/uploads/CEBMa-REA-Guideline.pdf.

- Bebeau, M. J., & Thoma, S. J. (2003). Guide for DIT-2. Minneapolis: Center for the study of ethical development. University of Minnesota.

- Beck, A. T., Ward, C. H., Mendelson, M., Mock, J., & Erbaugh, J. (1961). An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 4(6), 561–571. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004

- Beidas, R. S., & Kendall, P. C. (2010). Training therapists in evidence‐based practice: A critical review of studies from a systems‐contextual perspective. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 17(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01187.x

- Bem, S. L. (1981), Bem sex-role inventory. Professional Manual. APA PsycTests. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/t00748-000.

- Ben-Ezra, M., Lis, E., Błachnio, A., Ring, L., Lavenda, O., & Mahat-Shamir, M. (2018). Social workers’ perceptions of the association between role playing games and psychopathology. Psychiatric Quarterly, 89(1), 213–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-017-9526-7

- Billieux, J., Chanal, J., Khazaal, Y., Rochat, L., Gay, P., Zullino, D., & Van Der Linden, M. (2011). Psychological predictors of problematic involvement in massively multiplayer online roleplaying games: Illustration in a sample of male cybercafé players. Psychopathology, 44(3), 165–171. https://doi.org/10.1159/000322525

- Blackmon, W. D. (1994). Dungeons and dragons: The use of a fantasy game in the psychotherapeutic treatment of a young adult. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 48(4), 624–632. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.1994.48.4.624

- Bowman, S. L., & Lieberoth, A. (2018). Psychology and roleplaying games. In J. P. Zagal & S. Deterding (Eds)., Roleplaying Game Studies (pp. 245-164). Transmedia Foundations. , 245–264. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315637532-13

- Bowman, S. L. (2007). The psychological power of the roleplaying experience. Journal of Interactive Drama, 2(1), 1–15.

- Bratton, S., & Ray, D. (2000). What the research shows about play therapy. International Journal of Play Therapy, 9(1), 47. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/h0089440

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brodeur, N. (2018). Behind the scenes of the making of dungeons & dragons. The Seattles Times. Retrieved October 14, 2020, Retrieved https://www.seattletimes.com/life/lifestyle/behind-the-scenes-of-the-making-of-dungeons-dragons

- Brown, S., Cockett, P., & Yuan, Y. (2019). The neuroscience of Romeo and Juliet: An fMRI study of acting. Royal Society Open Science, 6(3), 181908. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.181908

- Brummel, B. J., Gunsalus, C. K., Anderson, K. L., & Loui, M. C. (2010). Development of roleplay scenarios for teaching responsible conduct of research. Science and Engineering Ethics, 16(3), 573–589. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-010-9221-7

- Carbonell, C. D. (2019). Chapter 3: Dungeons and dragons multiverse. In Dread trident: Tabletop roleplaying games and the modern fantastic. (pp. 80-108). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.3828/liverpool/9781789620573.001.0001

- Carnes, M. C., & Minds on fire. (2014). How role-immersion games transform college. Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674735606

- Carroll, J. L., & Carolin, P. M. Relationship between game playing and personality. (1989). Psychological Reports, 64(3), 705–706. 10.2466%2Fpr0.1989.64.3.705. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1989.64.3.705

- Carter, R., & Lester, D. (1998). Personalities of players of Dungeons and Dragons. Psychological Reports, 82(1), 182. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1998.82.1.182

- Cattell, R. B., Eber, H. W., & Tatsuoka, M. M. (1970). Handbook for the 16-personality factor questionnaire. Institute for Personality and Ability Testing.

- Chung, T. S. (2013). Table-top role playing game and creativity. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 8, 56–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2012.06.002

- Consumber, B., & Kjeldgaard, N. (2020). How dungeons and dragons is keeping people connected during the pandemic. Retrieved October 14, 2020, from https://www.nbcsandiego.com/news/investigations/nbc-7-responds/how-dungeons-and-dragons-is-keeping-people-connected-during-the-pandemic/2416421

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (2018). CASP cohort study checklist. [online] Retrieved from https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/CASP-Cohort-Study-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf

- D’Anastatasio, C. (2017). Therapists are using dungeons & dragons to get kids to open up. https://kotaku.com/therapists-are-using-dungeons-dragons-to-get-kids-to-1794806159

- Davey, L., Day, A., & Howells, K. (2005). Anger, over-control, and serious violent offending. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 10(5), 624–635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2004.12.002

- Davis, M. H. (1994). Empathy: A social psychological approach. Westview Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429493898

- Deighton, R. M., Gurris, N., & Traue, H. (2007). Factors affecting burnout and compassion fatigue in psychotherapists treating torture survivors: Is the therapist’s attitude to working through trauma relevant? Journal of Traumatic Stress, 20(1), 63–75. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20180

- DeRenard, L. A., & Kline, L. M. (1990). Alienation and the game Dungeons and Dragons. Psychological Reports, 66(3), 1219–1222. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1990.66.3c.1219

- Douse, N. A., & McManus, I. C. (1993). The personality of fantasy game players. British Journal of Psychology, 84(4), 505–509. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8295.1993.tb02498.x

- Dupuis, E. C., & Ramsey, M. A. (2011). The relation of social support to depression in massively multiplayer online role‐playing games. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 41(10), 2479–2491. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2011.00821.x

- Edmunds, J. M., Beidas, R. S., & Kendall, P. C. (2013). Dissemination and implementation of evidence–based practices: Training and consultation as implementation strategies. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 20(2), 152–165. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1111/cpsp.12031

- Eisenman, P., & Bernstein, A. (2021, March 31). Bridging the isolation: Online dungeons and dragons as group therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Counseling Service of Addison County, Inc. https://www.csac-vt.org/who_we_are/csac-blog.html/article/2021/03/31/bridging-the-isolation-online-dungeons-and-dragons-as-group-therapy-during-the-covid-19-pandemic

- Elms, A. C. (1967). Role playing, incentive, and dissonance. Psychological Bulletin, 68(2), 132. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/h0020186

- Enfield, G. (2007). Becoming the hero: The use of roleplaying games in psychotherapy. In L. C. Rubin (Ed.), Using superheroes in counseling and play therapy (pp. 227–241). Springer Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429454950

- Eysenck, H. J., & Eysenck, S. B. G. (1964). Manual of the Eysenck personality inventory. University of London Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/springerreference_184643

- Feng, J., Spence, I., & Pratt, J. Playing an action video game reduces gender differences in spatial cognition. (2007). Psychological Science, 18(10), 850–855. 10.1111%2Fj.1467-9280.2007.01990.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01990.x

- Game to Grow (2020). About game to grow. https://gametogrow.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Game-to-Grow-Press-Kit.pdf

- Gorman, D. M., Werner, J. M., Jacobs, L. M., & Duffy, S. W. (1990). Evaluation of an alcohol education package for non‐specialist health care and social workers. British Journal of Addiction, 85(2), 223–233. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1990.tb03075.x

- Hollander, E. M., & Craig, M. (2013). Working with sexual offenders via psychodrama. Sexual Offender Treatment, 8(2), 1–15.

- Hughes, G. (2021, July 3). Covid-19: Dungeons and dragons got us through lockdown. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-wales-57636378

- Hughes, J. (1988). Therapy is fantasy: Roleplaying, healing, and the construction of symbolic order. In Anthropology IV Honours, Medical Anthropology Seminar, Dept. of Prehistory & Anthropology, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia

- Jarvis, M. (2020, June 18). Dungeons & dragons is addressing problematic elements of the RPG’s races. Dicebreaker. https://www.dicebreaker.com/games/dungeons-and-dragons-5e/news/dungeons-and-dragons-addressing-problematic-races

- John, O. P., & Srivastava, S. (1999). The big five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research, 2(1999), 102–138.

- Just, R. M. (2018). The power in dice and foam swords: Gendered resistance in dungeons and dragons and live-action roleplay. [Master thesis, The University of Montana]. Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/11277.

- Kaufman, G. F., & Libby, L. K. (2012). Changing beliefs and behavior through experience-taking. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103(1), 1. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/a0027525

- Keulen-de Vos, M., van den Broek, E. P., Bernstein, D. P., Vallentin, R., & Arntz, A. (2017). Evoking emotional states in personality disordered offenders: An experimental pilot study of experiential drama therapy techniques. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 53, 80–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2017.01.003

- Kipper, D. A., & Ritchie, T. D. (2003). The effectiveness of psychodramatic techniques: A meta-analysis. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 7(1), 13. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/1089-2699.7.1.13

- Lankoski, P., & Järvelä, S. (2012). An embodied cognition approach for understanding role-playing. International Journal of Role-Playing, 3, 18–32.

- LeBaron, M., & Alexander, N. M. (2009). Death of the roleplay. In C. Honeyman, J. Coben, and G. De PaloEds. 2009, Rethinking Negotiation Teaching: Innovations for Context and Culture. (pp. 179-197). DRI Press. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3749380

- Leeds, S. M. (1995). Personality, belief in the paranormal, and involvement with satanic practices among young adult males: Dabblers versus gamers. Cultic Studies Journal, 12(2), 148–165.

- Lieberoth, A. (2013). Religion and the emergence of human imagination. In A. W. Geertz (Ed.), Origins of religion, cognition and culture (pp. 160–177). Acumen Publishing, Ltd.

- Lis, E., Chiniara, C., Biskin, R., & Montoro, R. (2015). Psychiatrists’ perceptions of role-playing games. Psychiatric Quarterly, 86(3), 381–384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-015-9339-5

- Mar, R. A., Oatley, K., & Peterson, J. B. (2009). Exploring the link between reading fiction and empathy: Ruling out individual differences and examining outcomes. Communications, 34(4), 407–428. https://doi.org/10.1515/COMM.2009.025

- Mar, R. A. The neural bases of social cognition and story comprehension. (2011). Annual Review of Psychology, 62(1), 103–134. 0066-4308/11/0110-0103$20.00. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120709-145406

- Matthews, M., Gay, G., & Doherty, G. (2014, April). Taking part: Roleplay in the design of therapeutic systems. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 643–652), Toronto, Ontario, Canada. https://doi.org/10.1145/2556288.2557103.

- Meriläinen, M. (2012). The self-perceived effects of the roleplaying hobby on personal development–a survey report. International Journal of Roleplaying, 3(1), 49–68.

- Meyer, M. L., Zhao, Z., & Tamir, D. I. (2019). Simulating other people changes the self. Journal of Experimental Psychology. General, 148(11), 1898. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/xge0000565

- Mittelmeier, J., Heliot, Y., Rienties, B., & Whitelock, D. (2015). The role culture and personality play in an authentic online group learning experience. In (P. Daly, K. Reid, P. Buckley, and S. Reeve. eds.), Proceedings of the 22nd EDINEB Conference: Critically Questioning Educational Innovation in Economics and Business: Human Interaction in a Virtualising World (pp. 139–149). EDiNEB Association, Milton Keynes, England.

- Moreno, J. L. (1978). Who shall survive? Beacon House Inc.

- Muñoz, R., Barcelos, T., Noël, R., & Kreisel, S. (2012, November). Development of software that supports the improvement of the empathy in children with autism spectrum disorder. In 2012 31st International Conference of the Chilean Computer Science Society (pp. 223–228). IEEE. Valparaíso, Chile. https://doi.org/10.1109/SCCC.2012.33.

- Myers, I. B. (1962). The Myers-Briggs type indicator: Manual (1962). Consulting Psychologists Press. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/14404-000.

- Petticrew, M., & Roberts, H. (2008). Systematic reviews in the social sciences: A practical guide. John Wiley & Sons.

- Pilon, M. (2019). The Rise of the Professional Dungeon Master. Bloomberg. Retrieved October 14, 2020, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2019-07-08/how-to-be-a-professional-dungeons-dragons-master-hosting-games

- Pithers, W. D. Maintaining treatment integrity with sexual abusers. (1997). Criminal Justice and Behavior, 24(1), 34–51. 10.1177%2F0093854897024001003. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854897024001003

- Premack, D., & Woodruff, G. (1978). Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 1(4), 515–526. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X00076512

- Rafaeli, E., Bernstein, D. P., & Young, J. (2011). The CBT distinctive features series. Schema therapy: Distinctive features. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Ramdoss, S., Machalicek, W., Rispoli, M., Mulloy, A., Lang, R., & O’Reilly, M. (2012). Computer-based interventions to improve social and emotional skills in individuals with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 15(2), 119–135. https://doi.org/10.3109/17518423.2011.651655

- Reed, P. G. (1986). Developmental resources and depression in the elderly: A longitudinal study. Nursing Research, 35(6), 368–374. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-198611000-00014

- Rivers, A., Wickramasekera, I. E., Pekala, R. J., & Rivers, J. A. (2016). Empathic features and absorption in fantasy role-playing. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 58(3), 286–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/00029157.2015.1103696

- Rosenthal, G. T., Soper, B., Folse, E. J., & Whipple, G. J. Role-play gamers and national guardsmen compared. (1998). Psychological Reports, 82(1), 169–170. 10.2466%2Fpr0.1998.82.1.169. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1998.82.1.169

- Rosselet, J. G., & Stauffer, S. D. (2013). Using group roleplaying games with gifted children and adolescents: A psychosocial intervention model. International Journal of Play Therapy, 22(4), 173. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/a0034557

- Schuller, K. (2016, October 13). SEXISM AND GENDER ISSUES IN TABLETOP GAMING. Her Campus. https://www.hercampus.com/school/uwindsor/sexism-and-gender-issues-tabletop-gaming

- Scouts. (2021). Dungeons & dragons. Retrieved February 26, 2021, from https://www.scouts.org.uk/supporters/dungeons-dragons

- Seton, M. (2008). ‘Post-dramatic’ stress: Negotiating vulnerability for performance. Proceedings of the 2006 Conference of the Australasian Association for Drama, Theatre and Performance Studies. Sydney, Australia.

- Shadish, W. R., Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (2002). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. W. R. Shedish, T. D. Cook, & D. T. Campbell. Houghton Mifflin.

- Simkins, D. (2010). Playing with ethics: Experiencing new ways of being in RPGs. In Karen Schrier & David Gibson (Eds.), Ethics and Game Design: Teaching Values Through Play (pp. 69–84). IGI Global.https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-61520-845-6.ch005

- Simon, A. (1987). Emotional stability pertaining to the game of Dungeons & Dragons. Psychology in the Schools, 24(4), 329–332. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6807(198710)24:4%3C329::AID-PITS2310240406/3E3.0.CO;2-9

- Spotorno, R., Picone, M., & Gentile, M. (2020, December). Designing an online dungeons & dragons experience for primary school children. In International Conference on Games and Learning Alliance (pp. 207–217). Springer, Cham, Laval, France. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-63464-3_20.

- Steen, F., & Owens, S. (2001). Evolution’s pedagogy: An adaptationist model of pretense and entertainment. Journal of Cognition and Culture, 1(4), 289–321. https://doi.org/10.1163/156853701753678305

- Stenros, J. (2015) Playfulness, play, and games: A constructionist ludology approach [Dissertation, University of Tampere] https://trepo.tuni.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/96986/978-951-44-9788-9.pdf?sequence=1

- Tellegen, A. (1982). Brief manual for the differential personality questionnaire (Unpublished manuscript). University of Minnesota, MN.

- Testoni, I., Bonelli, B., Biancalani, G., Zuliani, L., & Nava, F. A. (2020). Psychodrama in attenuated custody prison-based treatment of substance dependence: The promotion of changes in wellbeing, spontaneity, perceived self-efficacy, and alexithymia. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 68, 101650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2020.101650. Article.

- Trivasse, H., Webb, T. L., & Waller, G. (2020). A meta-analysis of the effects of training clinicians in exposure therapy on knowledge, attitudes, intentions, and behavior. Clinical Psychology Review, 80, 101887. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101887

- Wallach, M., & Kogan, N. (1965). Modes of thinking in young children. New York: Holt. Rinehart, & Winston.

- Waller, G. (2009). Evidence-based treatment and therapist drift. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47(2), 119–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2008.10.018

- Werth, M. (2018). Roleplay in the Chinese classroom. Master’s Thesis, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Masters Theses, 676. https://doi.org/10.7275/12026470.

- White, C. (2017). Dungeons & dragons is now being used as therapy. BBC. https://www.bbc.co.uk/bbcthree/article/ab3db202-341f-4dd4-a5e7-f455d924ce22

- Willoughby, R. R. (1932). Some properties of the Thurstone personality schedule and a suggested revision. The Journal of Social Psychology, 3(4), 401–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1932.9919168

- Wilson, D. L. (2007). An exploratory study on the players of “Dungeons and Dragons. Institute of Transpersonal Psychology.

- Wizards of the Coast. (2003). History of TSR. http://www.wizards.com/dnd/dndarchives_history.asp

- Worth, N. C., & Book, A. S. (2015). Dimensions of video game behavior and their relationships with personality. Computers in Human Behavior, 50, 132–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.03.056

- Wright, J. C., Weissglass, D. E., & Casey, V. Imaginative role-playing as a medium for moral development: Dungeons & Dragons provides moral training. (2020). Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 60(1), 99–129. 10.1177%2F0022167816686263. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167816686263

- Zayas, L. H., & Lewis, B. H. (1986). Fantasy roleplaying for mutual aid in children’s groups: A case illustration. Social Work with Groups, 9(1), 53–66. https://doi.org/10.1300/J009v09n01_05