ABSTRACT

Generation Z (Gen Z) has experienced unprecedented psychological challenges in recent history, and Asian American Gen Zers, in particular, bear a distinct mental health burden. This pilot study introduces Compassionate Home, Action Together (CHATogether)’s novel digital community program that promotes Asian American mental health through interactive theater and explores the impacts of theater skit development on Gen Zers’ mental health and family relationships. Here, we guide participants to develop skits using these stages: 1) identifying topics and collaborators; 2) planning the scene; 3) improvisation; 4) writing; 5) community engagement. We then explore the impact of the skit production process on participants’ emotional health through interviewing nine individuals and using thematic analysis of those anonymized transcripts. Results suggest that narrative writing, improvisation, and acting may hold a future for culturally adaptive and family-centered interventions for Asian American Gen Zers. A larger study scale is warranted for validity of potential clinical applications.

Generation Zers (born 1995–2009, Gen Zers) are the most racially diverse and social media-engaged, pragmatic thinkers of all U.S. generations (Katz et al., Citation2021). These adolescents and young adults are highly collaborative and imaginative in solving problems. They are the force driving toward a conscientious and equity-focused future, despite facing numerous stressors simultaneously – an unprecedented pandemic, global financial crisis, polarized society, gun violence, diminished reproductive rights, and climate change (Rue, Citation2018).

As a generation raised largely on cell phones and social media, young adults and teenagers frequently feel alone in a traumatized society (Katz et al., Citation2021). Although devices appear to connect us constantly, the pressure of “always-on” self-packaging for public consumption often creates more stress than relief (Grelle et al., Citation2023). A ten-year trend report from the CDC found that Gen Zers have increasingly experienced persistent feelings of sadness and hopelessness (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2023). This report found that young women, racial/ethnic minorities, and those identifying as LGBTQ are especially at high risk of poorer mental health. Interestingly, Asian American Gen Zers appear to be the least affected. Are they truly resilient? Or, is there unspoken agony inside?

The mask of the “model minority” myth renders Asian Americans invisible, inhibiting conversations on emotional challenges or seeking help despite their pressing mental health concerns and increased risk of suicidal behavior (Goodwill & Zhou, Citation2020; Lipson et al., Citation2018). They may face the invisible pressures of being perceived as academically successful and well-behaved, while minimizing mental health challenges such as low self-esteem, depression, and suicide (Chen et al., Citation2022; Choi et al., Citation2020). The first COVID-19 pandemic has indiscriminately isolated and depressed Gen Zers. In what has further exacerbated Asian American Gen Zers and their families’ decreasing wellness has been the second pandemic – anti-Asian discrimination and race-based cyberbullying (Choi et al., Citation2022; Patchin & Hinduja, Citation2023).

Gen Zers may have a more open sentiment toward mental illness and a higher rate of seeking treatment compared to previous generations (Bethune, Citation2019). In contrast, compared to other racial/ethnic groups, Asian Americans significantly underutilize mental health services despite their post-pandemic crises (Chen et al., Citation2022). This discrepancy suggests a variety of systemic and cultural barriers, such as a lack of culturally appropriate services, mistrust of the care system, perceptions of burdensomeness on others, challenges in discussing mental health problems with parents, and negative parental reactions to mental health utilization (Arora & Khoo, Citation2020; Tang & Masicampo, Citation2018). Many culturally informed mental health programs have made progress in addressing the needs of Asian Americans (Huey & Tilley, Citation2018; J. M. Kim et al., Citation2021; Lim & Chen, Citation2021; Xin et al., Citation2022). However, a critical mental health vacuum persists in connecting Asian American Gen Zers with their parents, families, and communities (Cai & Lee, Citation2022). Herein lies our motivation behind the development of Compassionate Home, Action Together (CHATogether) amidst the pressures of COVID-19 and anti-Asian racism.

Since the inception of CHATogether in 2019, our digital interactive theater programs have created safe spaces to address cultural identity dilemmas and the mental health stigma of Asian Americans and their families (Song et al., Citation2022). One effective way to encourage conversations on mental health in Asian American families has been through theater, using collective problem-solving (Berghs et al., Citation2022; de Witte et al., Citation2021; Orkibi et al., Citation2019). Improvisation (improv) theater helps improve psychological well-being (Schwenke et al., Citation2021) and guides families in finding a middle ground during conflict (Lloyd-Hazlett, Citation2021). Through theater storytelling on social media platforms such as Facebook, YouTube, and Zoom webinars, we have facilitated the expression of challenging content specific to Asian American teens, parents, clinicians, and community leaders. CHATogether has created 26 theater skits and live-performed 38 skit webinars in the United States and beyond. In this pilot initiative, we explored the impact of theater on Asian American Gen Zers’ emotional well-being by 1) introducing the CHATogether skit development protocol, and 2) examining the potential impacts of theater skit development on participants’ identity development, emotional health, and family relationships.

Method

Participants

Nine individuals (18–32 years old; 4 males; 5 females) with various levels of acculturation participated in the study, similar to those previously described (Song et al., Citation2022). Eight participants were of Asian descent, and one identified herself as an ally of Asian American mental wellness whose spouse is of Asian descent. Participants did not receive formal theater or improvisational training.

Procedure

CHATogether program description

The CHATogether skit is conceptualized partly from the “Theater of the Oppressed (TOP),” a participatory theater coined by Brazilian dramatist Augusto Boal. TOP promotes problem solving (Quinlan, Citation2010) and collective empowerment among participants to express their inner voice, ultimately leading to social change (Boal, Citation2000; Boehm & Boehm, Citation2003). The CHATogether skit incorporates elements of improvisation as “real-time acting,” allowing actors to continuously create roles and change personalities during the performance (Zenk et al., Citation2022). Improvisation allows actors to collectively create a “group mind” and coherent performance in the scene. Actors synchronize and anticipate their partners’ actions (Leander et al., Citation2023), which evolve into a support system as participants feel more comfortable with being vulnerable with each other (Gao et al., Citation2019).

Skit development

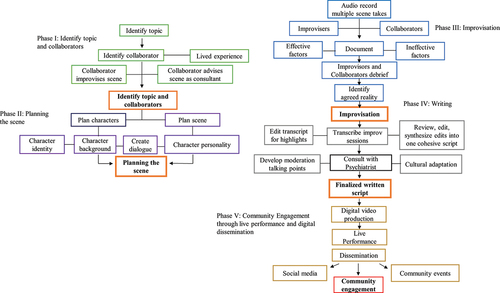

Participants were first guided to develop a CHATogether’s skit (either through writing, acting, or both), followed by a qualitative study as outlined below. We guided participants to create skits using a five-phase development protocol, including 1) identifying topics and collaborators, 2) planning the scene, 3) improvisation, 4) writing, and 5) community engagement through live performance and digital dissemination ( and ). Our skit video was shared on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eTl3BcEK41s&t=388s, and an example of a written skit was shown in Supplemental Material 1. Depending on the individual’s comfort level, participants developed skits based on personal experiences with their families. In some cases, collaborators were invited to provide feedback based on their experiences in the improvisation process. All participants consented to various steps of skit development in Phases I-V described in and and, including writing, acting, moderating, video production, and live improvisation at community webinars.

Table 1. Phases of skit development.

Study procedures

Between September 2021 to February 2022, we conducted individual, semi-structured interviews using Zoom video-conferencing with skit developing participants to explore the experiences of all three involvement types in CHATogether’s interactive theater program (acting, writing, or both). The institutional review board of Yale University (Protocol # 2000028490) approved the study. Semi-structured interviewing is a commonly used qualitative research methodology in health care, as it provides participants with key questions that guide the interview, while also allowing participants the flexibility to further explore existing and new ideas that are important to them (Kallio et al., Citation2016). Two lead authors (PW and EY) led individual interviews to explore topics such as participants’ relationships to the skit topics and characters they played, feelings toward their performance, challenges, learning points and opportunities for growth, therapeutic processes, reflection on parent-child roles, cultural identity, and mental health. Participants also discussed their thoughts on feasibility and acceptability of the skit developing process to identify if there were practical challenges, and the impact of their skit experiences in their personal lives and parental relationships. All participants gave verbal consent for audio recording. Interviews were then transcribed using Rev.com. An integrated detailed analysis was used to comprehensively examine the de-identified transcripts.

Data analysis

We used thematic analysis in an inductive manner, rooted in an interpretative phenomenological approach aimed to examine the participants’ personal and subjective experiences (Groenewald, Citation2004; Starks & Trinidad, Citation2007). We found this approach most suitable for guiding our data analysis, as it is used to understand the underlying qualities or essence of the lived experiences of a specific population within a specific context (Starks & Trinidad, Citation2007). In our case, we sought to understand the experiences of Asian American Gen Zers who participated in CHATogether’s skit development program during the COVID-19 pandemic. True to the phenomenology, codes were developed after analyzing and categorizing statements made by participants that seemed to address common features of the lived experience of the participants.

Using NVivo (QSR International), three authors (PW, SZ, & EY) worked independently to identify and organize individual codes and then co-developed a final codebook after several series of discussions with other investigators. Using a bottom-up method, we constructed the overarching themes and domains based on the codebook, each supported by several verbatim quotes as presented in & , and in text. We analyzed data iteratively until reaching theoretical sufficiency (Saunders et al., Citation2018), following accepted guidelines for qualitative study (Tong et al., Citation2007).

Table 2. Domain I: therapeutic impact. Participants quotation exemplars.

Table 3. Domain II: Feasibility and obstacles. Participants quotation exemplars.

Results

Of the nine participants, two participants (22.2%) portrayed actors (Actor 1 and Actor 2), two (22.2%) were skit writers (Writer 1 and Writer 2), and five (55.6%) participants both acted and wrote skits (Actor and writer 1, Actor and writer 2, Actor and writer 3, Actor and writer 4, and Actor and writer 5). We developed a framework of two overarching domains, each with underlying themes. Domain I: therapeutic impact before and after the involvement of skit development, included themes of (1) bicultural identity, (2) acculturative gap, (3) empathy among Asian American communities, and (4) mental health stigma. Domain II: feasibility and obstacles with themes described positives and challenges in (1) improv/skit writing, (2) acting, and (3) live performance and digital dissemination. Additional quotes are shown in & .

Domain I: therapeutic impact

Bicultural identity

Most participants were Gen Zers of Asian descent who either grew up or lived in the United States, so are, by definition, bicultural individuals (C. W. Cheung & Swank, Citation2019). Similarly, participants in this study were able to identify dual aspects of their identity, shaped by the cultural heritage of their families of origin and their experience growing up or living in the United States. They also acknowledged differences and, in several cases, the tension between the two. One participant described how being a minority influenced his relationship with his cultural heritage. “I definitely tried to reject my Asian identity or my heritage because I moved somewhere that’s very, majority of people were White … everyone was treating me a bit differently. I think that basically made me reject my heritage unconsciously.” [Actor and writer 4]

Through the skit productions, many participants found a cultural sense of community to share their experiences and feel understood in ways they may not have previously, as this participant stated that “ … it gives you the permission to find your heritage, your roots, the missing piece that you have been looking for or have been suppressing … ” [Actor and writer 4]

Acculturative gap

Participants highlighted the existence of an acculturative gap between Gen Zers and their immigrant parents. An acculturative gap describes a difference between youth and their parents in the rate of acculturation to a majority culture, where youth acculturate more quickly, which can exacerbate typical parent-child intergenerational differences. One participant noticed the mutual acknowledgment of cultural differences in her family communication and how that also impacted her mother’s point of view in disagreement, given that:

[the skit] brings up these issues to my mom for her to understand not necessarily my perspective, but … what I believe is right and good. And then for her to say, let’s not talk about this because we’re too different and it’s better to just respect each other and talk about things that we agree on. [Actor and writer 5]

Acculturative gaps also occur in ways to approach racial dilemmas in an immigrant family. After creating a skit on anti-Asian racism, one participant described a newfound desire to start a conversation with her parents:

… to explain it to my parents who have even less of an understanding of issues like racism or issues like what Asian Americans would face in general. I actually started talking to my mom about it. I never even really brought it up before, because I thought that it would scare her … I hope she feels okay talking to me about it if it happens. [Actor and writer 4]

Empathy among the Asian American community

Participants expressed diversity in their upbringing and relationship to different skit topics. Some who participated as actors described initial unfamiliarity with specific skit topics, but through their involvement as skit actors, they gained empathy. One participant was unfamiliar with anti-Asian racism, as she had recently moved to the United States. Through skit acting, she became more aware of other Asian Americans’ experiences and began to develop a sense of solidarity:

Even though I did not grow up with this kind of culture, nevertheless … I have come to identify with these issues and made them my own and I am fighting for them with the platform of leadership that I currently have in my school… [Actor 1]

Mental health stigma

Participants described barriers encountered in their families in acknowledging the existence of mental health conditions, the need for care, and the potential that skit production has in bringing these conversations to light. One participant described difficulty bringing up emotionally challenging conversations with their parents due to their parents’ own struggle as immigrants:

It’s definitely not something that you would talk about. I don’t want to make my parents worry because I’ve seen them struggling with their life. You have to justify yourself for being in this country constantly. So on top of that, you have to bring up, “I’m struggling.” Trying to seek out some sort of comfort from parents was difficult. [Actor and writer 4]

Through being a skit actor, one participant realized that she was able to humanize the character she played and the potential skit production has in reducing mental health stigma:

… being the parent who had alcoholism makes you … humanize things that are stigmatized in the community. For example, the Asian community will look down on the people who are addicted to alcohol and have these issues, but … if you act like that person and you have a moderation, you see what they’re going through … and have more understanding of what’s happening to them. Maybe that can help with the stigma. [Actor and writer 2]

Domain II: feasibility and obstacles

Improv/Skit writing

Participants were able to use skit writing to process their own experiences by recalling their lived child-parent interactions, emotions, and environment during those interactions. One participant drew from her own experiences with language barriers in her family in writing a script:

I think especially when writing or doing the skit where I identified with the characters more, I learned more about myself. Through writing it and everything, I feel like all my experiences and emotions, and everything came out more through that process. It let me reflect back on things more. [Actor and writer 2]

Conversely, skit writing could be challenging, because articulating past experiences into writing was unfamiliar and uncomfortable. One participant stated:

Where it was challenging was because it’s not something I have done before. It’s not something I do on a regular basis, so it was challenging to be able to articulate certain sentiments or events when it’s not something that I portrayed in writing in the past. [Writer 1]

Acting

Participants who acted in the skits described their experiences as overwhelmingly therapeutic and enjoyable, though some found it challenging to portray others’ narratives. One participant expressed acting helps process his emotions and to better understand his parent’s perspective:

Having to vocalize how I’m feeling and arguing with someone who’s playing my parent – being in that role helped me not to suppress my emotions and to work through things I had pushed down. Playing the opposite role as a parent helped me think about why they’re doing the things they’re doing and why we disagree. [Actor and writer 3]

While many participants gained empathy for others through role-playing, some were concerned about feeling unfit to portray another’s experience:

I was worried about me not being able to represent the Asian American culture, because then in the Asian American realm, you have issues like assimilation, racism, discrimination, and being part of the minority that I, [having lived] in a majority Asian country, did not necessarily grow up with … [Actor 1]

Live performance and digital dissemination

Participants described the final product of the skit performance as creative, effective, and impactful on actors and audiences. Potential impacts reported included delivering a meaningful message, creating dialogue beyond the skit, and raising awareness on important issues affecting the Asian American community. One participant described skit development as exceedingly genuine:

I think the final product … was overwhelmingly authentic. And I say that because I personally think that art is a medium that I experience intensely by the senses. You really can’t block out art the way you block out language. It’s actually very effective in getting messages across. [Actor 1]

Live performance can also make actors vulnerable, especially when the moderator asks probing questions about their behavior or comments in front of an audience. “During our skits … the middle [of the skit] is the mentalization process where the moderator kind of breaks down [or] freezes time. Having that part could be especially uncomfortable since I’m directly stating my emotions to the camera and to my parents … ” [Actor and writer 3]

Discussion

CHATogether has been a safe, creative space for young Asian Americans since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic (Song et al., Citation2022). Together, we process the pain stemming from increasing racial turmoil while addressing communication challenges within these families. CHATogether’s improvisation program has inspired team members to create skit videos and live-perform webinars to reach the broader Asian American community via social media.

Theater provides a powerful cathartic experience that allows us to connect with others and empower each other to build resilience. By playing a role, one may experience improved self-efficacy and confidence (Schwenke et al., Citation2021). The technique was an effective intervention in clinical settings, such as helping patients process their personal experiences, and improve their sense of identity, belonging, and hope (A. Cheung et al., Citation2022). Theater intervention is also associated with reduced anxiety and depressive symptoms (Krueger et al., Citation2019), and positive outcomes for immigrants, refugees, and ethnic minorities (E. Kim et al., Citation2017; Rousseau et al., Citation2014)

In this article, we developed a standardized protocol for skit production reproducibility. Our results suggest that participating in skit development can yield therapeutic impacts on personal and familial understanding of mental health among Asian American Gen Zers. In therapeutic contexts such as school counseling centers, private practices, and academic institutions, especially where Asian American individuals may underutilize mental health services, CHATogether’s skit development program may be incorporated to better reach and serve Asian American youth and their families to break the silence on Asian American mental health, understand relational health in Asian American families, and understanding the bi/multicultural self. Each of these three counseling practice issues will be explored in sequence.

Breaking the silence of Asian American mental health

The pandemic has taken valuable time, motivation, and opportunities away from Gen Zers as they emerge into adulthood. Many can become disengaged or pessimistic. However, after conducting hundreds of interviews and analyzing millions of digital language items, Katz et al. (Citation2021) found that Gen Zers are highly adaptive, flexible, collaborative, and authentically care for people. Their strengths are well equipped against current adversities. CHATogether is a good example where Gen Zers’ ingenuity tackles the mental health stigmas on social media platforms.

It is well known that Asian American communities resist mental health services, even with high rates of depression and suicide (Chen et al., Citation2022). For generations, concepts of burdening others, bringing shame, and losing face have been deep-rooted in Asian American families and communities (Tang & Masicampo, Citation2018). Young Gen Zers are conflicted when immigrant parents embrace “stoicism” against adversity and do not acknowledge their own or their children’s mental health struggles (Shaligram et al., Citation2022). Our results suggest that CHATogether skit production allows one to process complicated feelings and normalize mental health conversations. Through improvisation, writing, and acting, participants can connect with others who share similar experiences, serving as a starting point to reduce mental health stigma. Social media has only amplified CHATogether members’ voices and expanded their outreach outwardly, geographically, and inwardly to their families.

Understanding relational health in Asian American families

A Pew Research Center analysis found that 50% of young Americans aged 18 to 29 years live with their parents (Fadeyi & Horowitz, Citation2022). Many Gen Zers live with their families to save money, focus on their careers, or care for elderly parents. These financially savvy, goal-oriented, and responsible behaviors may be challenging to align with their parents’ expectations, creating conflict within families.

Second-generation immigrant Asian Americans in our study found their parents’ Confucianism-based hierarchical parenting and collectivism of prioritizing family harmony challenging to reconcile (Choi et al., Citation2008; B. S. K. Kim et al., Citation2001). At times parents can be disapproving, over-controlling, or intolerant of individual expression (Choi et al., Citation2008; Rhee et al., Citation2003). In some cases, expressions of love are indirect and represented by gestures such as cooking or cleaning (B. S. K. Kim et al., Citation2001).

Our results suggest that parent-Gen Zer conflicts increasingly stem from differences in communication styles and generational or cultural values. Improv can help families resolve conflict by allowing open communication and solving problems in a non-defensive manner (Lloyd-Hazlett, Citation2021). A CHATogether skit vividly depicts a power struggle between a parent and child, as neither side acknowledges that one can still be supportive without changing the other’s stance. By writing or acting out a “role reversal,” the participants actively immerse themselves in parental roles. The process opens the door to mentalization, promoting curiosity, and acceptance toward their parents (Byrne et al., Citation2020; Fonagy et al., Citation2018). The creative process enhances participants’ reflective functioning to understand their parents’ viewpoints and expressions (Katznelson, Citation2014). It has been interesting to receive feedback from parents in live-performed webinars, as they have shared that passively watching these performances motivates them to improve their empathy and communication with their children. As shown in our YouTube video and in Supplemental Material 1, a skit moderator can guide a live reflection and discussion on differences in communication styles between family members.

Understanding Bi/Multi-cultural self

Gen Zers are growing up in a world of communication that operates at an increased speed and scope through Internet superhighways. The abundance of information and its instantaneous dissemination can be overwhelming. Teens and young adults must be self-reliant and work collaboratively to find their unique identities while reconciling the negative stereotypes of delayed adulthood or failed expectations.

Additionally, young Asian Americans reckon with the question of cultural belonging. Many embraced multiple cultural identities in their psychological development while growing up in immigrant households. The conflicting cultural exposures without parental support due to language barriers or historical trauma can be challenging (Choi et al., Citation2022; Rhee et al., Citation2003). While fearing rejection from adverse community experiences such as discrimination and racism, many struggle to integrate their multicultural selves.

CHATogether’s skit development provides a simulation to re-expose the participants’ relational difficulties with their parents or extrinsic societal events. The process synthesizes a collective narrative across generations, which leads to an understanding of self, culture, vulnerability, and pride. The simulated moments may trigger unpleasant memories in participants. However, with support, re-exposure allows guided perspectives of a safer relationship within the family or community, initiates alternative healing dialogs, and ultimately finds a co-existing sense of bicultural self. Our results suggest that the more participants identified their personal experiences within the skits, the better they processed and articulated difficult emotions or past relationships. Skit development allows one to “disinhibit” emotions typically not validated in one’s environments or expressed in an unconscious state of mind. The therapeutic concepts of CHATogether skit development may resemble exposure therapy (Felsman et al., Citation2020) and cognitive processing therapy for treating individuals with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and anxiety-related disorders (Asmundson et al., Citation2019).

Implications for future practice

CHATogether is an accessible, community-engaging platform to reduce mental health disparities (Song et al., Citation2022). It has the flexibility to deliver care to a broader audience through various digital venues. CHATogether‘s strength can be utilized as a care model in addition to conventional mental health care systems. It has the potential to relieve strain on the current state of increased demand and workforce shortage in mental health services since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (Crocker et al., Citation2023). Previous work has shown that community members with informal training have effectively met Asian American community mental health needs (Weng & Spaulding-Givens, Citation2017). The current skit production protocol can be used as a component in one-on-one, family, or peer group settings, creating an opportunity for Asian American individuals who may not otherwise engage in conventional therapy. It can also be utilized as a process or media to improve child-parent communication in child- and family-centered mental health services. Lastly, the theater narrative captures cultural nuances that provide skit developers and viewers a valuable psycho-cultural education.

Limitations and future research directions

While the skit development process has many benefits, several challenges and limitations exist. Firstly, developing skills through writing, acting, and performing without formal drama training could be challenging for some participants. However, participants identified that the skit’s relatability to their personal experiences aligns with the feasibility and enjoyment of skit development. Secondly, some participants found the skits provocative, as some scenarios were too similar to their personal experiences. An anticipatory “trigger warning” and post-skit production debriefing would help provide appropriate emotional support. Third, our current sample size did not intend to represent the entire Asian American community, as “Asian American” designates a heterogenous diaspora of cultures and unique individuals. To increase accessibility for diverse audiences, especially in cases of families who speak languages other than English, future work that includes skit captions and the involvement of bilingual skit developers would be invaluable.

A significant gap exists in therapeutic interventions targeting the mental health stressors that affect the Asian American identity, family, and community. This pilot qualitative study demonstrates the potential of the CHATogether skit development program may provide a promising culturally-responsive intervention. Our preliminary findings highlight the need for further research in Asian American communities, with particular focus on child-parent relationships, communication, and acculturation experiences. There are very few mental health prevention programs aim at improving child-parent relationships in Asian American families, with the majority of these family-focused programs targeting mainly on parenting skills and practices (Dong & Rao, Citation2023; Lau et al., Citation2011; Qiu et al., Citation2022). This warrants further exploration of programs that support Asian Americans as they navigate familial conflicts, acculturative stress, and racial discrimination. Specifically, improv interventions were effective in promoting collective family problem solving (Lloyd-Hazlett, Citation2021). Using validated psychometric measures, future studies would aim to evaluate participants’ experiences before, during, and after CHATogether skit development program. A longitudinal follow up to investigate whether participants may apply their learned skills to their life experiences would be important. Moreover, studies should include larger and more diverse sample sizes including various Asian American subgroups, especially Central Asians, South Asians, Southeast Asians, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islanders, and multiracial and multiethnic subgroups.

Conclusion

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, Gen Zers have experienced difficulties associated with their mental health and a sense of identity as they interface with the digital and tangible world. Intersectional vulnerabilities among Asian American Gen Zers and the high mental health burden with multiple barriers to seeking mental health services make a critical call for culturally responsive care in Asian American communities. The study reveals that CHATogether’s novel interactive theater program brings positive therapeutic effects on Asian American Gen Zers through 1) providing a less stigmatized space for mental health discussions; 2) promoting healthy communication and mentalization in immigrant families despite cross-cultural and -generational differences; and 3) fostering bi/multi-cultural identity development through solidarity within the Asian American communities. Although future study is needed, CHATogether’s skit development method of creative narrative writing, improvisation, and acting is feasible, and may provide culturally responsive intervention for Gen Zers and beyond.

Author contribution

PW and SD contributed equally to this work. EY, AL, KB, and GV designed the study; EY, PW, and SD conducted data collection and analysis to finalize the thematic codebook and overarching themes using NVivo. All authors participated in writing, editing, and approving the final version of the manuscript. EY supervised the integrity of the study and submitted manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Dr. Chiun Yu Hsu from State University of New York at Buffalo for his critical review and editing during manuscript revision.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arora, P. G., & Khoo, O. (2020). Sources of stress and barriers to mental health service use among Asian immigrant-origin youth: A qualitative exploration. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(9), 2590–2601. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-020-01765-7

- Asmundson, G. J. G., Thorisdottir, A. S., Roden Foreman, J. W., Baird, S. O., Witcraft, S. M., Stein, A. T., Smits, J. A. J., & Powers, M. B. (2019). A meta-analytic review of cognitive processing therapy for adults with posttraumatic stress disorder. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 48(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2018.1522371

- Berghs, M., Prick, A. J. C., Vissers, C., & van Hooren, S. (2022). Drama therapy for children and adolescents with psychosocial problems: A systemic review on effects, means, therapeutic attitude, and supposed mechanisms of change. Children, 9(9), 1358. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9091358

- Bethune, S. (2019). Gen Z more likely to report mental health concerns. Monitor on Psychology, 50(1). https://www.apa.org/monitor/2019/01/gen-z

- Boal, A. (2000). Theater of the oppressed. Pluto Press.

- Boehm, A., & Boehm, E. (2003). Community theatre as a means of empowerment in social work: A case study of women’s community theatre. Journal of Social Work, 3(3), 283–300. https://doi.org/10.1177/146801730333002

- Byrne, G., Murphy, S., & Connon, G. (2020). Mentalization-based treatments with children and families: A systematic review of the literature. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 25(4), 1022–1048. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104520920689

- Cai, J., & Lee, R. M. (2022). Intergenerational communication about historical trauma in Asian American families. Adversity and Resilience Science, 3(3), 233–245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42844-022-00064-y

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). Youth risk behavior survey data summary & trends report: 2011-2021. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/YRBS_Data-Summary-Trends_Report2023_508.pdf

- Chen, B. C., Lui, J. H. L., Benson, L. A., Lin, Y.-J. R., Ponce, N. A., Innes-Gomberg, D., & Lau, A. S. (2022). After the crisis: Racial/ethnic disparities and predictors of care use following youth psychiatric emergencies. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 52(3), 360–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2022.2127103

- Cheung, A., Agwu, V., Stojcevski, M., Wood, L., & Fan, X. (2022). A pilot remote drama therapy program using the co-active therapeutic theater model in people with serious mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal, 58(8), 1613–1620. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-022-00977-z

- Cheung, C. W., & Swank, J. M. (2019). Asian American identity development: A bicultural model for youth. Journal of Child and Adolescent Counseling, 5(1), 89–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/23727810.2018.1556985

- Choi, Y., He, M., & Harachi, T. W. (2008). Intergenerational cultural dissonance, parent–child conflict and bonding, and youth problem behaviors among Vietnamese and Cambodian immigrant families. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37(1), 85–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-007-9217-z

- Choi, Y., Jeong, E., & Park, M. (2022). Asian Americans’ parent–child conflict and racial discrimination may explain mental distress. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 9(1), 18–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/23727322211068173

- Choi, Y., Park, M., Noh, S., Lee, J. P., & Takeuchi, D. (2020). Asian American mental health: Longitudinal trend and explanatory factors among young Filipino- and Korean Americans. SSM-Population Health, 10, 100542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100542

- Crocker, K. M., Gnatt, I., Haywood, D., Butterfield, I., Bhat, R., Lalitha, A. R. N., Jenkins, Z. M., & Castle, D. J. (2023). The impact of COVID-19 on the mental health workforce: A rapid review. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 32(2), 420–445. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.13097

- de Witte, M., Orkibi, H., Zarate, R., Karkou, V., Sajnani, N., Malhotra, B., Ho, R. T. H., Kaimal, G., Baker, F. A., & Koch, S. C. (2021). From therapeutic factors to mechanisms of change in the creative arts therapies: A scoping review. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 678397. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.678397

- Dong, S., & Rao, N. (2023). Associations between parental well-being and early learning at home before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: Observations from the China family panel studies. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1163009. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1163009

- Fadeyi, D., & Horowitz, J. M. (2022). Americans more likely to say it’s a bad thing than a good thing that more young adults live with their parents. Pew. https://policycommons.net/artifacts/2653248/americans-more-likely-to-say-its-a-bad-thing-than-a-good-thing-that-more-young-adults-live-with-their-parents/

- Felsman, P., Gunawardena, S., & Seifert, C. M. (2020). Improv experience promotes divergent thinking, uncertainty tolerance, and affective well-being. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 35, 100632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2020.100632

- Fonagy, P., Gergely, G., Jurist, E. L., & Target, M. (2018). Affect regulation, mentalization and the development of the self. Routledge.

- Gao, L., Peranson, J., Nyhof-Young, J., Kapoor, E., & Rezmovitz, J. (2019). The role of “improv” in health professional learning: A scoping review. Medical Teacher, 41(5), 561–568. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2018.1505033

- Goodwill, J. R., & Zhou, S. (2020). Association between perceived public stigma and suicidal behaviors among college students of color in the U.S. Journal of Affective Disorders, 262(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.10.019

- Grelle, K., Shrestha, N., Ximenes, M., Perrotte, J., Cordaro, M., Deason, R. G., & Howard, K. (2023). The generation gap revisited: Generational differences in mental health, maladaptive coping behaviors, and pandemic-related concerns during the initial COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Adult Development, 30(4), 381–392. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-023-09442-x

- Groenewald, T. (2004). A phenomenological research design illustrated. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 3(1), 42–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690400300104

- Huey, S. J., & Tilley, J. L. (2018). Effects of mental health interventions with Asian Americans: A review and meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 86(11), 915–930. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000346

- Izzo, G. (1997). The art of play: The new genre of interactive theatre. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

- Kallio, H., Pietilä, A. M., Johnson, M., & Kangasniemi, M. (2016). Systematic methodological review: Developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 72(12), 2954–2965. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13031

- Katznelson, H. (2014). Reflective functioning: A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 34(2), 107–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2013.12.003

- Katz, R., Ogilvie, S., Shaw, J., & Woodhead, L. (2021). Gen Z, explained: The art of living in a digital age. University of Chicago Press. https://books.google.com/books?id=0lQ_EAAAQBAJ

- Kim, E., Boutain, D., Kim, S., Chun, J. J., & Im, H. (2017). Integrating faith-based and community-based participatory research approaches to adapt the Korean parent training program. Journal of Pediatric Nursing-Nursing Care of Children & Families, 37, 70–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2017.05.004

- Kim, J. M., Kim, S. J., Hsi, J. H., Shin, G. H. R., Lee, C. S., He, W., & Yang, N. (2021). The “Let’s Talk!” conference: A culture-specific community intervention for Asian and Asian American student mental health. Community Mental Health Journal, 57(6), 1001–1009. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-020-00715-3

- Kim, B. S. K., Yang, P. H., Atkinson, D. R., Wolfe, M. M., & Hong, S. (2001). Cultural value similarities and differences among Asian American ethnic groups. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 7(4), 343–361. https://doi.org/10.1037/1099-9809.7.4.343

- Krueger, K. R., Murphy, J. W., & Bink, A. B. (2019). Thera-prov: A pilot study of improv used to treat anxiety and depression. Journal of Mental Health, 28(6), 621–626. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2017.1340629

- Lau, A. S., Fung, J. J., Ho, L. Y., Liu, L. L., & Gudino, O. G. (2011). Parent training with high-risk immigrant Chinese families: A pilot group randomized trial yielding practice-based evidence. Behavior Therapy, 42(3), 413–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2010.11.001

- Leander, K., Carter-Stone, L., & Supica, E. (2023). “We got so much better at reading each other’s energy”: Knowing, acting, and attuning as an improv ensemble. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 32(2), 250–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2022.2154157

- Lim, C. T., & Chen, J. A. (2021). A novel virtual partnership to promote Asian American and Asian international student mental health. Psychiatric Services, 72(6), 736–739. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.202000198

- Lipson, S. K., Kern, A., Eisenberg, D., & Breland-Noble, A. M. (2018). Mental health disparities among college students of color. Journal of Adolescent Health, 63(3), 348–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.04.014

- Lloyd-Hazlett, J. (2021). Improv-ing clinical work with stepfamilies. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 16(2), 231–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/15401383.2020.1762817

- Orkibi, H., Feniger-Schaal, R., & Shiu, C.-S. (2019). Integrative systematic review of psychodrama psychotherapy research: Trends and methodological implications. Public Library of Science ONE, 14(2), e0212575. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212575

- Patchin, J. W., & Hinduja, S. (2023). Cyberbullying among Asian American youth before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of School Health, 93(1), 82–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.13249

- Qiu, Z., Guo, Y., Wang, J., & Zhang, H. (2022). Associations of parenting style and resilience with depression and anxiety symptoms in Chinese middle school students. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 897339. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.897339

- Quinlan, E. (2010). New action research techniques: Using participatory theatre with health care workers. Action Research, 8(2), 117–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476750309335204

- Rhee, S., Chang, J., & Rhee, J. (2003). Acculturation, communication patterns, and self-esteem among Asian and Caucasian American adolescents. Adolescence, 38(152), 749–768.

- Rousseau, C., Beauregard, C., Daignault, K., Petrakos, H., Thombs, B. D., Steele, R., Vasiliadis, H. M., Hechtman, L., & Botbol, M. (2014). A cluster randomized-controlled trial of a classroom-based drama workshop program to improve mental health outcomes among immigrant and refugee youth in special classes. Public Library of Science ONE, 9(8), e104704. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0104704

- Rue, P. (2018). Make way, millennials, here comes Gen Z. About Campus, 23(3), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086482218804251

- Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., Burroughs, H., & Jinks, C. (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality & Quantity, 52(4), 1893–1907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8

- Schwenke, D., Dshemuchadse, M., Rasehorn, L., Klarholter, D., & Scherbaum, S. (2021). Improv to improve: The impact of improvisational theater on creativity, acceptance, and psychological well-being. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 16(1), 31–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/15401383.2020.1754987

- Shaligram, D., Chou, S., Chandra, R. M., Song, S., & Chan, V. (2022). Addressing discrimination against Asian American and Pacific Islander youths: The mental health provider’s role. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 61(6), 735–738. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2021.11.021

- Sheets-Johnstone, M. (1981). Thinking in movement. The Journal of Aesthetics & Art Criticism, 39(4), 399–407. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540_6245.jaac39.4.0399

- Song, J. E., Ngo, N. T., Vigneron, J. G., Lee, A., Sust, S., Martin, A., & Yuen, E. Y. (2022). CHATogether: A novel digital program to promote Asian American Pacific Islander mental health in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 16(1), 76. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-022-00508-4

- Starks, H., & Trinidad, S. B. (2007). Choose your method: A comparison of phenomenology, discourse analysis, and grounded theory. Qualitative Health Research, 17(10), 1372–1380. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732307307031

- Tang, Y., & Masicampo, E. J. (2018). Asian American college students, perceived burdensomeness, and willingness to seek help. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 9(4), 344–349. https://doi.org/10.1037/aap0000137

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- Weng, S. S., & Spaulding-Givens, J. (2017). Informal mental health support in the Asian American community and culturally appropriate strategies for community-based mental health organizations. Human Service Organizations, Management, Leadership & Governance, 41(2), 119–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/23303131.2016.1218810

- Xin, R., Fitzpatrick, O. M., Ho Lam Lai, P., Weisz, J. R., & Price, M. A. (2022). A systematic narrative review of cognitive-behavioral therapies with Asian American youth. Evidence-Based Practice in Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 7(2), 198–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/23794925.2022.2042872

- Zenk, L., Hynek, N., Schreder, G., & Bottaro, G. (2022). Toward a system model of improvisation. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 43, 100993. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2021.100993