ABSTRACT

Introduction

Depression and anxiety are prevalent mental health conditions in older adulthood. Despite sleep disturbance being a common comorbidity in late-life depression and anxiety, it is often discounted as a target for treatment. The current review aims to establish whether cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is effective in treating concomitant sleep disturbance in depressed and anxious older adults and to review evidence supporting whether CBT interventions targeting anxiety and depression, or concurrent sleep disturbance, have the greatest effectiveness in this client group.

Method

A systematic database search was conducted to identify primary research papers evaluating the effectiveness of CBT interventions, recruiting older adults with symptoms of depression and/or anxiety, and employing a validated measure of sleep disturbance. The identified papers were included in a narrative synthesis of the literature.

Results

Eleven identified studies consistently support reductions in sleep disturbance in elderly participants with depression and anxiety in response to CBT. Most CBT interventions in the review included techniques specifically targeting sleep, and only one study directly compared CBT for insomnia (CBT-I) with a CBT-I intervention also targeting depressive symptoms, limiting the ability of the review to comment on whether interventions targeting sleep disturbance or mental health symptoms have superior effectiveness.

Conclusion

The extant research indicates that CBT interventions are effective in ameliorating sleep disturbance in late-life depression and anxiety. Future high-quality research is required to substantiate this finding and to compare the effectiveness of CBT-I and CBT for depression and anxiety in this group to inform clinical practice.

Introduction

Depression and anxiety are common, and often comorbid mental health conditions in older adulthood (Byers et al., Citation2010; Préville et al., Citation2008). Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is the most common anxiety disorder in the elderly (Beekman et al., Citation1998), primarily characterized by excessive and uncontrollable worry as well as somatic symptoms, including sleep disturbance (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). Depressive symptoms of clinical severity are reportedly present in 8–16% of community-dwelling older adults (Blazer, Citation2003), with core symptoms including depressed mood and lack of interest or pleasure (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013).

Sleep disturbance increases with age, with 20–40% of the older adults reporting problems with sleep (Ancoli-Israel & Cooke, Citation2005). Sleep disturbance refers to a reduction in sleep quality, which can occur as a consequence of clinical sleep disorders, such as obstructive sleep apnea, restless leg syndrome and insomnia; be related to environmental or behavioral factors, such as light or caffeine intake; or in relation to other chronic and coexisting medical and psychological conditions (Reynolds & Adams, Citation2019; Sorathia & Ghori, Citation2016). Insomnia is a prevalent cause of sleep disturbance in older adults (Morphy et al., Citation2007); and is characterized by difficulty initiating and maintaining sleep or waking up too early, resulting in impairment of daytime functioning (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013; National Institute of Health, Citation2005). A fourth characteristic, nonrestorative or poor-quality sleep, has frequently been included in the definition (National Institute of Health, Citation2005). Chronic sleep disturbance can have concerning associations for older adults, including increased risk of falls (Stone et al., 2008), cognitive impairment (Yaffe et al., Citation2014), poor physical functioning (Dam et al., Citation2008) and increased risk of mortality (Pollak et al., Citation1990). Furthermore, residual insomnia following recovery from depressive and anxiety disorders has been reported to be a risk factor for suicidal ideation (McCall et al., Citation2010) and future relapse (Cho et al., Citation2008; Dombrovski et al., Citation2007; Ohayon & Roth, Citation2003).

Given that sleep disturbance is often an associated symptom of depressive (Riemann, Citation2007) and anxiety (Magee & Carmin, Citation2010) disorders, and the increasing incidence with age, it is unsurprising that a high number of older adults with depression and anxiety report sleep-related difficulties (Brenes et al., Citation2009; Spira et al., Citation2009). The traditional view has perceived sleep disturbances as a secondary consequence, or a symptom, of psychological disorders; and as such the treatment of sleep disorders has been given low priority (Freeman et al., Citation2017). However, it is now thought that disrupted sleep plays a contributory causal role in the bidirectional relationship with mental health problems, such as depression and anxiety, with problems sleeping likely to influence both the onset and trajectory of mental health difficulties (Baglioni et al., Citation2011; Freeman et al., Citation2017). In response, the previous distinction made between primary and secondary insomnia has been replaced by a diagnosis of insomnia disorder with/without concurrent clinically comorbid conditions in the DSM-V (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fifth Edition; American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013; National Institute of Health, Citation2005). This significant shift in recognition of the comorbid nature of insomnia advocates for the consideration and treatment of insomnia independently, and in addition to, concurrent mental health difficulties (Reynolds III & O’Hara, Citation2013).

CBT interventions have an evidence base for the treatment of late-life anxiety (Gould et al., Citation2012), depression (Pinquart et al., Citation2007) and insomnia (Lovato et al., Citation2014; Sivertsen et al., Citation2006). Therefore, it is reasonable to expect that CBT may also be effective for anxious and/or depressed older adults with concomitant sleep disturbance (Bush et al., Citation2012). As well as CBT interventions targeting psychiatric symptoms, there is a robust body of evidence supporting the effectiveness of CBT-I (CBT for insomnia; Alessi & Vitiello, Citation2015; Montgomery, Citation2004), which includes practical skills to modify unhelpful cognitive and behavioral patterns that maintain and exacerbate insomnia. Due to increasing pressure on health service resources, there is a need to identify and utilize evidence-based treatments which target commonly occurring comorbidities, to maximize service-user outcomes and improve the efficiency of service provision.

The current systematic review aims to identify and synthesize the extant research to address two primary questions. Firstly, the review aims to appraise the existing evidence to establish whether CBT interventions are effective in the treatment of concomitant sleep disturbance in depressed and anxious older adults. Secondly, the review aims to comment on evidence supporting whether CBT interventions targeting anxiety and depression, or comorbid sleep disturbance or insomnia (CBT-I), have the greatest effectiveness in this client group.

Method

Search strategy

The systematic search utilized three electronic databases: PsycInfo, Medline and Scopus. Existing gray literature was also searched through the EThOS database. The search included studies published before December 2020. Search criteria were translated into four categories of key words that were used to identify papers from the title, abstract and subject headings. These categories of key words selected studies that (a) included participants with symptoms of depression or an anxiety disorder (key words: anxi* OR depress* OR affect OR mood); (b) included older adult participants (key words: “older adult*” OR “older people” OR elderly OR aging OR aging OR geriatric*); (c) included a validated measure of sleep quality, sleep disturbance or insomnia (key words: sleep* OR insomnia*); and (d) included a CBT intervention (key words: “cognitive behav*” OR CBT). Additionally, all papers included in the review were searched for relevant references and citations. Hand-searching of citation networks of the three identified measures of sleep was also completed.

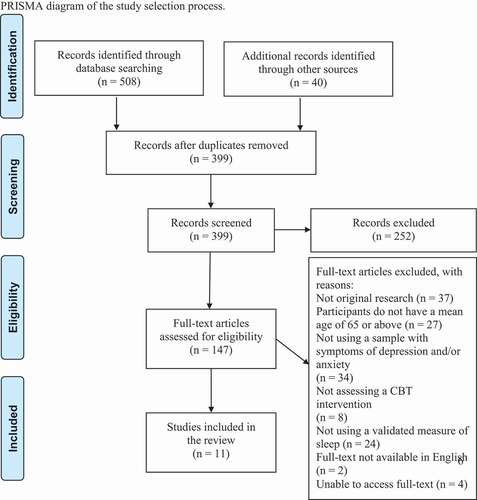

Study selection

Three-hundred and ninety-nine references were identified as part of the systematic search. The titles and abstracts were screened by two reviewers to establish if they were relevant to the current review question. The full text of all relevant articles was then independently reviewed by the two authors to determine if the study met the review inclusion and exclusion criteria. Initial interrater agreement of study eligibility was 89%. Any discrepancies in rating were discussed in a calibration meeting until a consensus on study eligibility was reached. displays the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram.

Study eligibility was established using the following inclusion criteria:

The study utilized a validated measure of sleep quality to assess the impact of intervention on concomitant sleep disturbance. Subjective measures of sleep quality or disturbance considered for review inclusion included, but were not exclusive to, the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI; Bastien et al., Citation2001), the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI; Buysse et al., Citation1989) and Consensus Sleep Diary (Carney et al., Citation2012). Objective measures of sleep quality or disturbance, including polysomnography and actigraphy, would also meet review inclusion if used to monitor change as a function of psychological intervention.

The study recruited older adult participants. Older adult status is defined differently across countries, with health services in the United Kingdom using a threshold age of 65 years and above, and research studies from the United States primarily defining those aged 60 years or above as an older adult. As stipulating a minimum age of 65 for eligibility in the current review would have greatly reduced the scope of the research, agreement was reached that studies with a mean participant age of 65 years or above would be considered for review inclusion.

The research participants were reported to experience symptoms of depression and/or anxiety. For inclusion in the current review, the study participants required symptoms of anxiety and/or depression meeting clinical thresholds. Clinical severity could be established using DSM criteria (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, e.g., American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013) or using a previously established diagnosis of an anxiety or depressive disorder. Furthermore, studies would be considered for inclusion in the review when participants met clinical thresholds on validated measures of symptoms of depression (e.g., the Geriatric Depression Scale; Yesavage, Citation1988) and/or anxiety (e.g the Penn State Worry Questionnaire; Meyer et al., Citation1990)

The study evaluated the effectiveness of a CBT intervention. Third-wave variations of CBT (e.g., Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy or Acceptance and Commitment Therapy) were not included in the current review.

Studies were excluded if they met the following criteria:

The paper was not a primary journal article (e.g., systematic reviews, meta-analyses, book chapters).

The research was primarily conducted in participants with a significant cognitive impairment, for example, research offering intervention tailored to participants with a diagnosis of dementia.

The full-text paper could not be located or was not available in English.

Data extraction

Data was extracted by the primary author and reviewed by the second author. Differences were resolved by discussion until a consensus was reached. Data extracted included; (1) the first author’s surname, (2) year of publication, (3) country of origin, (4) sample size, (5) mean age and standard deviation of the sample at baseline, (6) participant gender, (7) description of the content of the CBT intervention and modality of service delivery, (8) the comparison condition (for randomized controlled trials), (9) the measure of sleep quality used, and whether this was a primary or secondary outcome measure, (10) other outcome measures used, (11) relevant descriptive or inferential statistics demonstrating the intervention's impact on (a) sleep quality and (b) mental health outcomes. Study protocol papers and other primary or secondary results papers were reviewed for extracting relevant data for the summary of evidence table, when needed. When the necessary data was not available, research authors were contacted and asked to provide this information.

Data synthesis

The data extraction process highlighted a significant overlap of data in the identified papers, with four studies (Bush et al., Citation2012; Freshour et al., Citation2016; Nadorff et al., Citation2014; Stanley et al., Citation2014) in the review reporting data from two original trials (Stanley et al., Citation2014, Citation2009). Due to the heterogeneity in study design and overlapping participant data resulting in non-independence of the studies, utilizing meta-analytic methods to synthesize the data would be inappropriate. Findings were therefore combined and summarized in a narrative synthesis. The narrative synthesis aimed to organize study findings into descriptive patterns and provide an assessment of the strength of the evidence for drawing conclusions in service of the aims of the review (as per guidelines for conducting narrative synthesis; Popay et al., Citation2006).

Quality assessment

The quality assessment process was completed independently by two reviewers. Initial interrater agreement across items on the quality assessment measure was 87%. The discrepancies in quality ratings given were discussed until a consensus was reached. Quality assessment of the papers was conducted for two reasons: to consider the findings of the papers in respect of the quality of the methodology and to assess the research quality of the field. The Effective Public Health Practice Project quality assessment tool (Thomas et al., Citation2004) was chosen to evaluate the quality of included papers as it has been identified as appropriate for simultaneously assessing a range of quantitative intervention designs (Armijo-Olivo et al., Citation2012). The tool has six subscales covering selection bias, study design, control of confounders, blinding procedures, data collection methods and study attrition. Each subscale is assigned a quality rating: weak, moderate, or strong. The subscale ratings inform the global rating assigned to each study. None of the papers in the review were removed following quality assessment. However, important limitations of the studies highlighted in the quality assessment process are addressed in the results section. The quality assessment table can be found in .

Table 1. Quality ratings from the EPHPP quality assessment tool.

Results

Eleven papers were identified meeting review eligibility criteria, comprising data collected from 1286 participants across three countries (). The majority of the papers (81%) in the review investigate the effects of CBT interventions for late-life anxiety, primarily GAD. The studies utilize a range of methodological designs, CBT interventions, modalities of service delivery, and measures of sleep disturbance. The remainder of the review will collate and summarize the extant body of literature to examine if CBT interventions are effective in reducing sleep disturbance in depressed and/or anxious older adults.

Table 2. Review studies.

Anxiety

Randomized trials of CBT targeting symptoms of anxiety

Despite the prevalence of late-life anxiety and concomitant sleep disturbance, only eight randomized trials evaluate CBT interventions in the treatment of self-reported sleep problems in late-life anxiety. Five studies utilize data collected from three large-scale randomized trials conducted by Stanley et al. (Citation2009, Citation2014, Citation2018). Studies using these large cohorts, although differing in primary study aims, consistently find that CBT interventions, delivered by therapists with varying degrees of experience, have a positive impact on sleep disturbance in older adults with symptoms of anxiety. The remaining three trials examine telephone CBT (CBT-T). The studies utilize varied methodologies, but consistently report that CBT-T for anxiety results in reductions in the levels of sleep disturbance post-intervention.

Treatment in two trials (Stanley et al., Citation2014, Citation2009) were informed by the Stanley et al. (Citation2004) manual targeting symptoms of GAD in older adults in primary care settings. Notably, the manual includes an optional module on sleep skills if sleep disturbance was identified as a significant problem for clients. Specifically, this module included sleep hygiene skills, encouraging clients to set a consistent sleep schedule, limit the use of the bedroom, exit the bedroom if unable to sleep within 20 minutes and eliminate daytime naps. The two studies based on the earlier (Stanley et al., Citation2009) RCT, Bush et al. (Citation2012) and Nadorff et al. (Citation2014) assessed sleep disturbance in self-selecting older adults with GAD to investigate the impact of CBT on sleep quality and bad dream frequency, respectively. Both studies used the PSQI (Buysse et al., Citation1989), which was validated by Bush et al. (Citation2012) in the same cohort. Using the full PSQI measure Bush et al. found that CBT resulted in significantly greater reductions in PSQI scores than usual care, and at follow-up the participants receiving CBT reported better subjective sleep quality, shorter sleep latency and less frequent sleep disturbances, relative to those receiving usual care, although component scores were not corrected for multiple comparisons. This study was deemed to be of weak quality primarily due to high study attrition and lack of control for baseline group differences. In a study of moderate quality, Nadorff et al. completed a secondary analysis of this data focusing specifically on the impact of CBT on bad dream frequency, using a single item from the PSQI. This single item fails to capture bad dream content, severity, or distress. Participants randomized to the CBT condition were observed to report a greater reduction in bad dream frequency across treatment duration, and had fewer bad dreams at post-treatment, compared to participants receiving usual care.

A similar pattern of results is observed in the later Stanley et al. (Citation2014) RCT and follow-up study (Freshour et al., Citation2016), using the ISI (Bastien et al., Citation2001). Given the increasing number of older adults requiring mental healthcare and demand for psychological providers, Stanley et al. (Citation2014) conducted a further large-scale RCT evaluating the effectiveness of the same CBT intervention protocol delivered by lay providers to older adults with GAD. The study can be commended on the provision of supervision and measurement of treatment adherence, given the disparity of experience between therapists. In line with the main study outcomes assessing anxiety and depressive symptoms, lay and expert providers offered interventions which were equivalent in reducing insomnia symptoms, and both were statistically superior to treatment-as-usual. In the context of a high rate of study attrition (12.5%), Freshour et al. demonstrated that the positive outcomes of CBT, including reductions in sleep disturbance, were maintained 6 and 12 months after treatment completion, and did not significantly vary between lay and expert providers at the follow-up timepoints.

Stanley et al. (Citation2018) examined the effectiveness of a different CBT intervention on late-life worry. The study can be praised for acknowledging the underrepresentation of adults from low-income and minority groups in clinical research and addressing the lack of pertinent treatments factors for this group in traditional CBT methods (Areán et al., Citation2010) by creating a more sensitive intervention protocol (Stanley et al., Citation2016) and highlighting the importance of community-based outreach and screening for anxiety/worry in underserved populations. Similarly to aforementioned studies, Stanley et al. used the ISI to track changes in sleep disturbance as a function of the intervention. In a similar pattern to the observed reductions in worry/anxiety, the Calmer Life intervention resulted in moderate reductions in insomnia symptoms; however, these reductions were not statistically superior to the comparison condition (enhanced community care) at either the 6-month or 9-month follow-up point.

Three trials examined the effects of telephone CBT (CBT-T) on sleep disturbance in participants with late-life GAD (Brenes et al., Citation2016, Citation2020, Citation2012). In the Brenes et al. (Citation2012) study, scores on the ISI suggested greater improvements in insomnia severity in the CBT-T group post-intervention, relative to the information-only control condition, but in a similar trend to other clinical measures, this differential treatment effect was not maintained at the 6-month follow-up period. Assessments were conducted by interviewers blinded to the condition; however, the study had no measure of treatment compliance or therapist adherence. Brenes et al. (Citation2016) aimed to analyze secondary outcomes of an earlier RCT (Brenes et al., Citation2015). The treatment intervention was similar to that delivered in the Brenes et al. (Citation2012) study, however, to control for the common factors of therapy, non-directive supportive therapy (NST) was selected as the control. There is a high rate of missing data over the study follow-up, with the ISI data missing for 15–27% of participants. It was reported that symptoms of insomnia declined, on average, among participants in both interventions; however, those in the CBT intervention demonstrated a significantly greater improvement in sleep than NST over a 12-month follow-up period. A later, large randomized preference trial by Brenes et al. (Citation2020) extended these findings in a trial comparing CBT-T with yoga for the treatment of worry in older adults. Study findings suggest that CBT-T was significantly superior to yoga in reducing scores on the ISI, although both interventions did produce improvements in insomnia symptoms, worry and anxiety. The study found no preference or selection effects on any of the outcomes. The results suggest that CBT and yoga could both be useful interventions to address worry and anxiety in older adults, providing clinicians with treatment options. However, for those with concomitant sleep disturbances, CBT demonstrated superior treatment effects.

Single case experimental design study of CBT targeting symptoms of anxiety

In a small-scale and uncontrolled study, Landreville et al. (Citation2016) used a single-case experimental design to test the effectiveness of a CBT-T intervention for three older adults with GAD. At baseline all three participants had sleep disturbance meeting diagnostic criteria for insomnia, which reduced to non-clinical levels at post intervention and 6-month follow-up, a change that was significant for each participant according to a calculated reliable change index.

Summary

Given the high comorbidity between insomnia and late-life GAD, and the predominance of CBT interventions in the treatment of both conditions, there is a paucity of evidence investigating the role of CBT in the treatment of the comorbidity, with only nine studies reporting sleep outcomes in this area. Furthermore, the evidence available is of weak to moderate quality, with low rates of agreement to participate and sample populations that are somewhat unrepresentative of older adults accessing services. The nine identified studies consistently support that CBT interventions result in reduced levels of sleep disturbance in elderly participants with GAD. When compared to treatment-as-usual (n = 2), information–only (n = 1), NST (n = 1), and yoga (n = 1), CBT consistently demonstrated superior performance in reducing self-reported problems with sleep. Also, with the current pressures on health resources and the increasing use of telephone supported self-help interventions to improve access to services, the findings that CBT-T produces similar reductions in insomnia to face-to-face CBT are of clinical interest. It is important to note that the CBT interventions in each study, with the exception of Landreville et al. (Citation2016) and Stanley et al. (Citation2018), contained an optional session focused on sleep management or sleep hygiene. However, content and completion rate of the modules targeting sleep disturbance has largely been unreported. Therefore, without supplementary analysis comparing sleep improvement in participants opting for this additional module, it is difficult to confirm if the improvements in sleep quality are resulting entirely from targeted sleep management skills, or secondary to the observed improvements in anxiety symptoms resulting from CBT techniques.

Depression

Evidence investigating the impact of CBT interventions on sleep disturbance in older persons with depression is similarly underdeveloped, with the systematic search only identifying two studies. Furthermore, one of the identified studies (Lichstein et al., Citation2013) is of weak quality, and has a small sample size (n = 5) which limits the ability to draw robust conclusions in this population. The studies, Lichstein et al. (Citation2013) and Sadler et al. (Citation2018), differ from the research conducted in late-life anxiety in that the recruitment procedures specify participants with comorbid depression and insomnia reaching clinical levels of severity. Furthermore, the treatment interventions in both studies are designed to target concurrent symptoms of depression and insomnia.

In a small-scale pilot study, Lichstein et al. (Citation2013) assessed the feasibility of CBT-T using five uncontrolled case studies to develop the treatment protocol for a later RCT (Scogin et al., Citation2018). In both studies the minimum age for participation was lowered to 50 years to stimulate recruitment, resulting in the later RCT not meeting eligibility for the current review. CBT treatment in this study was equally divided between targeting symptoms of insomnia and depression. There was a significant improvement in all sleep characteristics between baseline and post-treatment, as well as a reduction in the ISI, which was reduced from clinical levels at baseline, to non-clinical levels at post-treatment and follow-up.

In a later, superior quality RCT, Sadler et al. (Citation2018) built on the findings of Lichstein et al. (Citation2013) to establish if CBT-I was effective for comorbid depression and insomnia, and to examine if CBT-I with additional components targeting depression (CBT-I+) would produce superior outcomes. There was high treatment retention, with 96% of participants completing the interventions. It was observed that CBT-I and CBT-I+ conditions both resulted in significant reductions in depression, insomnia severity and improvements in sleep quality at post-treatment and follow-up, and were both superior to psychoeducation. There was, however, no significant difference between the CBT-I and CBT-I+ conditions in reduction of depressive or insomnia symptoms, which the authors attribute to lack of statistical power due to under-recruitment.

Summary

The limited research in this area makes it difficult to draw robust conclusions; however, the extant literature indicates that CBT interventions are effective in reducing sleep disturbance in depressed older adults, with the most robust study (Sadler et al., Citation2018) suggesting its superiority to psychoeducation. Sadler et al. can be commended on the attempt to distinguish between the effectiveness of interventions purely targeting sleep disturbance and those designed to target comorbid mood disturbance; however, it is unfortunate that this study was underpowered to provide a conclusive result. Further research is certainly required to confirm the effectiveness of CBT interventions on sleep disturbance in older adults with depression, and to directly compare CBT interventions targeting depressive symptoms or insomnia in this population to make recommendations for clinical practice.

Discussion

Summary of findings

Despite the high degree of co-occurrence in sleep disturbances and late-life depressive and anxiety disorders, and the calls for comorbid insomnia to be highlighted as a treatment priority; the literature is significantly underdeveloped investigating the effects of CBT interventions on concomitant sleep disturbance, with only eleven studies identified in the extant literature measuring sleep. Furthermore, the evidence available is mostly of weak to moderate quality, with consistently low rates of agreement to participate and sample populations that are unrepresentative of older adults accessing services. Overall, the research trend indicates that CBT interventions are effective in ameliorating sleep disturbance in depressed and anxious elderly participants. However, future, high-quality research is required to substantiate this trend.

The majority of studies (82%) included, largely optional, techniques specifically targeting sleep problems; however, the content and completion rates of these modules were predominantly unreported. Only one study (Sadler et al., Citation2018) directly compared CBT-I with a CBT-I intervention also targeting depression symptoms, but was underpowered to find differential effects of treatment on sleep disturbance post-intervention. No conclusions can, therefore, be drawn regarding whether the improvements in sleep quality are due to targeted sleep management skills, or secondary to the observed improvements in symptoms of depression and anxiety. Future, high quality, research is needed to directly compare the effectiveness of CBT-I and CBT for depression and anxiety for older adults, to establish any potential differences in the effectiveness of these interventions and inform recommendations for clinical practice.

Limitations of the field and directions for future research

Given the limited extant literature addressing the research question, further, high-quality studies are required to provide substantive evidence that CBT interventions have beneficial outcomes on sleep disturbance in late-life GAD and depression. Limitations of the field are discussed to make recommendations for future research.

Future clinical trials are required to directly compare the efficacy of CBT-I and CBT for depression and anxiety, with and without a sleep management component, to establish differences in the efficacy of these interventions to make recommendations for clinical practice. The paucity of studies specifically comparing interventions limits speculation on mechanisms underlying the observed impact of CBT interventions on sleep disturbance and insomnia. It could be hypothesized that a reduction in levels of sleep disruption may be secondary to a reduction in anxiety and depressive symptoms, which were largely the primary focus of intervention in the reviewed studies. However, most interventions also incorporated optional modules on sleep hygiene, which could have promoted better sleep quality, which has in turn been found to reduce mood disturbance (Franzen & Buysse, Citation2008).

A number of studies included in the review report samples with high representation of females with high levels of education, which are not representative of the older adult population accessing mental health services. Furthermore, the mean age in each study ranges between 65 and 70 years of age, with some studies recruiting participants less than 60 years of age, whom would not access older adult services. Research shows that the mean age of older adults utilizing services tends to be higher (mean = 74.4) than in the reviewed studies, with greater parity between males and females (43%, 57%, respectively; Garrido et al., Citation2011). It is recommended that future research, recruiting participants representative of those accessing mental health services, would increase the generalizability of the research findings to clinical practice within older adult services.

Future research should consider undertaking a comprehensive and objective assessment of sleep. Each of the studies in the review use self-report measures of sleep, which have low-to-moderate agreement with objective sleep measures, especially in older adulthood (Hughes et al., Citation2018; Unruh et al., Citation2008). Furthermore, composite scores of sleep disturbance are primarily utilized across the described research, potentially masking treatment effects on specific sleep features, given the multifaceted nature of sleep in old age (Roepke & Ancoli-Israel, Citation2010). This is particularly relevant as psychiatric diagnoses, such as GAD, have been associated with differences in specific subcomponents of sleep (e.g., lowered sleep quality and greater daytime dysfunction; Ramsawh et al., Citation2009) which may be more important to target and measure when assessing the outcome of a CBT intervention. Finally, none of the studies completed a detailed clinical sleep assessment, to establish any functional or sleep impairments (e.g., sleep disordered breathing, periodic limb movement disorder) which are common in older adults (Neikrug & Ancoli-Israel, Citation2010) and could influence sleep quality and limit the effectiveness of treatment. Future research is required, with the primary aim of investigating the effects of CBT intervention on sleep disturbance in late-life mental health, incorporating a comprehensive sleep assessment.

Limitations of the current review

A limitation of the current review is the influence of publication and outcome-reporting bias, as research has higher success of publication when the results are statistically significant and positive, and articles tend to concentrate on results that are significant (Dwan et al., Citation2008). Despite the current review extending the scope of the search to thesis papers, the review is still influenced by the file drawer problem. The search strategy was designed to comprehensively identify relevant papers; however, there is no guarantee that the included research represents the absolute extent of the literature in this field. Furthermore, the exclusion criteria limited studies only to those published in English language, limiting the contribution from non-English language journals. Despite this, only one non-English language study was identified in the full-text review stage and the English translation of the abstract suggested that the analyses in the paper were not relevant to the review research questions.

Conclusion

The extant research consistently supports that face-to-face and telephone CBT interventions result in reduced levels of sleep disturbance in elderly participants with depression and anxiety. When compared to treatment-as-usual (n = 2), psychoeducation (n = 1), information–only (n = 1), NST (n = 1), and yoga (n = 1), CBT demonstrated superior performance in reducing self-reported problems with sleep quality. However, future, high-quality research is required to substantiate this conclusion. The majority of studies in the review included CBT interventions incorporating techniques specifically targeting sleep problems, which were often optional. Only one study in the review directly compared CBT-I with a CBT-I intervention also targeting depression symptoms, but was underpowered to find differential effects of treatment on sleep disturbance post-intervention. As such, there is insufficient evidence to determine whether the observed improvements in sleep quality are due to targeted sleep management skills, or related to the observed improvements in symptoms of depression and anxiety. Future research is needed to directly compare the effectiveness of CBT-I and CBT interventions for depression and anxiety to inform recommendations for clinical practice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alessi, C., & Vitiello, M. V. (2015). Insomnia (primary) in older people: Non-drug treatments. BMJ Clinical Evidence, 2015, 2302. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4429264/

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th. text revised.

- Ancoli-Israel, S., & Cooke, J. R. (2005). Prevalence and comorbidity of insomnia and effect on functioning in elderly populations. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 53(S7), S264–S271. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53392.x

- Areán, P. A., Mackin, S., Vargas-Dwyer, E., Raue, P., Sirey, J. A., Kanellopolos, D., & Alexopoulos, G. S. (2010). Treating depression in disabled, low-income elderly: A conceptual model and recommendations for care. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 25(8), 765–769. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.2556

- Armijo-Olivo, S., Stiles, C. R., Hagen, N. A., Biondo, P. D., & Cummings, G. G. (2012). Assessment of study quality for systematic reviews: A comparison of the cochrane collaboration risk of bias tool and the effective public health practice project quality assessment tool: Methodological research. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 18(1), 12–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01516.x

- Baglioni, C., Battagliese, G., Feige, B., Spiegelhalder, K., Nissen, C., Voderholzer, U., Lombardo, C., & Riemann, D. (2011). Insomnia as a predictor of depression: A meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. Journal of Affective Disorders, 135(1–3), 10–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2011.01.011

- Bastien, C. H., Vallières, A., & Morin, C. M. (2001). Validation of the insomnia severity index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Medicine, 2(4), 297–307. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S1389-9457(00)00065-4

- Beekman, A. T., Bremmer, M. A., Deeg, D. J., Van Balkom, A. J., Smit, J. H., De Beurs, E., Van Dyck, R., & Van Tilburg, W. (1998). Anxiety disorders in later life: A report from the longitudinal aging study Amsterdam. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 13(10), 717–726. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1166(1998100)13:10<717::AID-GPS857>3.0.CO;2-M

- Blazer, D. G. (2003). Depression in late life: Review and commentary. The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 58(3), M249–M265. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/58.3.M249

- Brenes, G. A., Danhauer, S. C., Lyles, M. F., Anderson, A., & Miller, M. E. (2016). The effects of telephone-delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy and nondirective supportive therapy on sleep, health-related quality of life, and disability*. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 24(10), 846–854. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2016.04.002

- Brenes, G. A., Danhauer, S. C., Lyles, M. F., Hogan, P. E., & Miller, M. E. (2015). Telephone-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy and telephone-delivered nondirective supportive therapy for rural older adults with generalized anxiety disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 72(10), 1012–1020. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1154

- Brenes, G. A., Divers, J., Miller, M. E., Anderson, A., Hargis, G., & Danhauer, S. C. (2020). Comparison of cognitive-behavioral therapy and yoga for the treatment of late-life worry: A randomized preference trial*. Depression and Anxiety, 37(12), 1194–1207. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/da.23107

- Brenes, G. A., Miller, M. E., Stanley, M. A., Williamson, J. D., Knudson, M., & McCall, W. V. (2009). Insomnia in older adults with generalized anxiety disorder. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 17(6), 465–472. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181987747

- Brenes, G. A., Miller, M. E., Williamson, J. D., McCall, W., Knudson, M., & Stanley, M. A. (2012). A randomized controlled trial of telephone-delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy for late-life anxiety disorders*. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 20(8), 707–716. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/JGP.0b013e31822ccd3e

- Bush, A. L., Armento, M. E., Weiss, B. J., Rhoades, H. M., Novy, D. M., Wilson, N. L., Kunik, M. E., & Stanley, M. A. (2012). The Pittsburgh sleep quality index in older primary care patients with generalized anxiety disorder: Psychometrics and outcomes following cognitive behavioral therapy*. Psychiatry Research, 199(1), 24–30. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2012.03.045

- Buysse, D. J., Reynolds III, C. F., Monk, T. H., Berman, S. R., & Kupfer, D. J. (1989). The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Research, 28(2), 193–213. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4

- Byers, A. L., Yaffe, K., Covinsky, K. E., Friedman, M. B., & Bruce, M. L. (2010). High occurrence of mood and anxiety disorders among older adults: The national comorbidity survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67(5), 489–496. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.35

- Carney, C. E., Buysse, D. J., Ancoli-Israel, S., Edinger, J. D., Krystal, A. D., Lichstein, K. L., & Morin, C. M. (2012). The consensus sleep diary: Standardizing prospective sleep self-monitoring. Sleep, 35(2), 287–302. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.1642

- Cho, H. J., Lavretsky, H., Olmstead, R., Levin, M. J., Oxman, M. N., & Irwin, M. R. (2008). Sleep disturbance and depression recurrence in community-dwelling older adults: A prospective study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 165(12), 1543–1550. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07121882

- Dam, T. T. L., Ewing, S., Ancoli-Israel, S., Ensrud, K., Redline, S., & Stone, K. (2008). Association between sleep and physical function in older men: The osteoporotic fractures in men sleep study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 56(9), 1665–1673. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01846.x

- Dombrovski, A. Y., Mulsant, B. H., Houck, P. R., Mazumdar, S., Lenze, E. J., Andreescu, C., Reynolds, C. F., & Cyranowski, J. M. (2007). Residual symptoms and recurrence during maintenance treatment of late-life depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 103(1–3), 77–82. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2007.01.020

- Dwan, K., Altman, D. G., Arnaiz, J. A., Bloom, J., Chan, A.-W., Cronin, E., Easterbrook, P. J., Von Elm, E., Gamble, C., Ghersi, D., Ioannidis, J. P. A., Simes, J., Williamson, P. R., & Decullier, E. (2008). Systematic review of the empirical evidence of study publication bias and outcome reporting bias. PloS One, 3(8), e3081. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0003081

- Franzen, P. L., & Buysse, D. J. (2008). Sleep disturbances and depression: Risk relationships for subsequent depression and therapeutic implications. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 10(4), 473–481. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2008.10.4/plfranzen

- Freeman, D., Sheaves, B., Goodwin, G. M., Yu, L.-M., Nickless, A., Harrison, P. J., Emsley, R., Luik, A. I., Foster, R. G., Wadekar, V., Hinds, C., Gumley, A., Jones, R., Lightman, S., Jones, S., Bentall, R., Kinderman, P., Rowse, G., Brugha, T., Gregory, A. M., … Espie, C. A. (2017). The effects of improving sleep on mental health (OASIS): A randomised controlled trial with mediation analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 4(10), 749–758. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30328-0

- Freshour, J. S., Amspoker, A. B., Yi, M., Kunik, M. E., Wilson, N., Kraus-Schuman, C., Cully, J. A., Teng, E., Williams, S., Masozera, N., Horsfield, M., & Stanley, M. (2016). Cognitive behavior therapy for late-life generalized anxiety disorder delivered by lay and expert providers has lasting benefits. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 31(11), 1225–1232. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4431

- Garrido, M. M., Kane, R. L., Kaas, M., & Kane, R. A. (2011). Use of mental health care by community-dwelling older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 59(1), 50–56. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03220.x

- Gould, R. L., Coulson, M. C., & Howard, R. J. (2012). Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders in older people: A meta-analysis and meta-regression of randomized controlled trials. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 60(2), 218–229. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03824.x

- Hughes, J. M., Song, Y., Fung, C. H., Dzierzewski, J. M., Mitchell, M. N., Jouldjian, S., Josephson, K. R., Alessi, C. A., & Martin, J. L. (2018). Measuring sleep in vulnerable older adults: A comparison of subjective and objective sleep measures. Clinical Gerontologist, 41(2), 145–157. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2017.1408734

- Landreville, P., Gosselin, P., Grenier, S., Hudon, C., & Lorrain, D. (2016). Guided self-help for generalized anxiety disorder in older adults*. Aging & Mental Health, 20(10), 1070–1083. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2015.1060945

- *Lichstein, K. L., Scogin, F., Thomas, S. J., Dinapoli, E. A., Dillon, H. R., & McFadden, A. (2013). Telehealth cognitive behavior therapy for co-occurring insomnia and depression symptoms in older adults. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(10), 1056–1065. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22030

- Lovato, N., Lack, L., Wright, H., & Kennaway, D. J. (2014). Evaluation of a brief treatment program of cognitive behavior therapy for insomnia in older adults. Sleep, 37(1), 117–126. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.3320

- Magee, J. C., & Carmin, C. N. (2010). The relationship between sleep and anxiety in older adults. Current Psychiatry Reports, 12(1), 13–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-009-0087-9

- McCall, W. V., Blocker, J. N., D’Agostino Jr, R., Kimball, J., Boggs, N., Lasater, B., & Rosenquist, P. B. (2010). Insomnia severity is an indicator of suicidal ideation during a depression clinical trial. Sleep Medicine, 11(9), 822–827. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2010.04.004

- Meyer, T. J., Miller, M. L., Metzger, R. L., & Borkovec, T. D. (1990). Development and validation of the Penn state worry questionnaire. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 28(6), 487–495. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(90)90135-6

- Montgomery, P., & Dennis, J. (2004). A systematic review of non-pharmacological therapies for sleep problems in later life. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 8(1), 47–62. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S1087-0792(03)00026-1

- Morphy, H., Dunn, K. M., Lewis, M., Boardman, H. F., & Croft, P. R. (2007). Epidemiology of insomnia: A longitudinal study in a UK population. Sleep, 30(3), 274–280.

- *Nadorff, M. R., Porter, B., Rhoades, H. M., Greising, A. J., Kunik, M. E., & Stanley, M. A. (2014). Bad dream frequency in older adults with generalized anxiety disorder: Prevalence, correlates, and effect of cognitive behavioral treatment for anxiety. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 12(1), 28–40. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2012.755125

- National Institute of Health. (2005). NIH state of science conference on manifestations and management of chronic insomnia in adult. NIH Consensus and State of the Science Statements, 22 (2), 1–36. https://consensus.nih.gov/2005/insomniastatement.pdf

- Neikrug, A. B., & Ancoli-Israel, S. (2010). Sleep disorders in the older adult – A mini-review. Gerontology, 56(2), 181–189. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1159/000236900

- Ohayon, M. M., & Roth, T. (2003). Place of chronic insomnia in the course of depressive and anxiety disorders. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 37(1), 9–15. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3956(02)00052-3

- Pinquart, M., Duberstein, P. R., & Lyness, J. M. (2007). Effects of psychotherapy and other behavioral interventions on clinically depressed older adults: A meta-analysis. Aging & Mental Health, 11(6), 645–657. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860701529635

- Pollak, C. P., Perlick, D., Linsner, J. P., Wenston, J., & Hsieh, F. (1990). Sleep problems in the community elderly as predictors of death and nursing home placement. Journal of Community Health, 15(2), 123–135. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01321316

- Popay, J., Roberts, H., Sowden, A., Petticrew, M., Arai, L., Rodgers, M., Britten, N., Roen, K. & Duffy, S. (2006). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC methods programme. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Mark_Rodgers4/publication/233866356_Guidance_on_the_conduct_of_narrative_synthesis_in_systematic_reviews_A_product_from_the_ESRC_Methods_Programme/links/02e7e5231e8f3a6183000000/Guidance-on-the-conduct-of-narrative-synthesis-in-systematic-reviews-A-product-from-the-ESRC-Methods-Programme.pdf

- Préville, M., Boyer, R., Grenier, S., Dubé, M., Voyer, P., Punti, R., Baril, M.-C., Streiner, D. L., Cairney, J., & Brassard, J. (2008). The epidemiology of psychiatric disorders in quebec’s older adult population. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 53(12), 822–832. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370805301208

- Ramsawh, H. J., Stein, M. B., Belik, S.-L., Jacobi, F., & Sareen, J. (2009). Relationship of anxiety disorders, sleep quality, and functional impairment in a community sample. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 43(10), 926–933. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.01.009

- Reynolds, A. C., & Adams, R. J. (2019). Treatment of sleep disturbance in older adults. Journal of Pharmacy Practice and Research, 49(3), 296–304. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/jppr.1565

- Reynolds III, C. F., & O’Hara, R. (2013). DSM-5 sleep-wake disorders classification: Overview for use in clinical practice. American Journal of Psychiatry, 170(10), 1099–1101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13010058

- Riemann, D. (2007). Insomnia and comorbid psychiatric disorders. Sleep Medicine, 8(S4), S15–S20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S1389-9457(08)70004-2

- Roepke, S. K., & Ancoli-Israel, S. (2010). Sleep disorders in the elderly. Indian Journal of Medical Research, 131, 302–310. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20308755/

- *Sadler, P., McLaren, S., Klein, B., Harvey, J., & Jenkins, M. (2018). Cognitive behavior therapy for older adults with insomnia and depression: A randomized controlled trial in community mental health services. Sleep, 41(8), 1–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsy104

- Scogin, F., Lichstein, K., DiNapoli, E. A., Woosley, J., Thomas, S. J., LaRocca, M. A., Mieskowski, L., Parker, C. P., Yang, X., Parton, J., McFadden, A., Geyer, J. D., & Byers, H. D. (2018). Effects of integrated telehealth-delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression and insomnia in rural older adults. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 28(3), 292–309. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/int0000121

- Sivertsen, B., Omvik, S., Pallesen, S., Bjorvatn, B., Havik, O. E., Kvale, G., Nielsen, G. H., & Nordhus, I. H. (2006). Cognitive behavioral therapy vs zopiclone for treatment of chronic primary insomnia in older adults. JAMA, 295(24), 2851–2858. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.295.24.2851

- Sorathia, L. T., & Ghori, U. K. (2016). Sleep disorders in the elderly. Current Geriatrics Reports, 5(2), 110–116. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s13670-016-0175-8

- Spira, A. P., Stone, K., Beaudreau, S. A., Ancoli-Israel, S., & Yaffe, K. (2009). Anxiety symptoms and objectively measured sleep quality in older women. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 17(2), 136–143. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181871345

- Stanley, M. A., Diefenbach, G. J., & Hopko, D. R. (2004). Cognitive behavioral treatment for older adults with generalized anxiety disorder: A therapist manual for primary care settings. Behavior Modification, 28(1), 73–117. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445503259259

- Stanley, M. A., Wilson, N., Shrestha, S., Amspoker, A. B., Armento, M., Cummings, J. P., Evans-Hudnall, G., Wagener, P., & Kunik, M. E. (2016). Calmer life: A culturally tailored intervention for anxiety in underserved older adults. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 24(8), 648–658. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2016.03.008

- Stanley, M. A., Wilson, N. L., Novy, D. M., Rhoades, H. M., Wagener, P. D., Greisinger, A. J., Cully, J. A., & Kunik, M. E. (2009). Cognitive behavior therapy for generalized anxiety disorder among older adults in primary care: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 301(14), 1460–1467. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.458

- *Stanley, M. A., Wilson, N. L., Shrestha, S., Amspoker, A. B., Wagener, P., Bavineau, J., Turner, M., Fletcher, T. L., Freshour, J., Kraus-Schuman, C., & Kunik, M. E. (2018). Community-based outreach and treatment for underserved older adults with clinically significant worry: A randomized controlled trial. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 26(11), 1147–1162. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2018.07.011

- *Stanley, M. A., Wilson, N. L., Amspoker, A. B., Kraus-Schuman, C., Wagener, P. D., Calleo, J. S., Cully, J. A., Teng, E., Rhoades, H. M., Williams, S., Masozera, N., Horsfield, M., & Kunik, M. E. (2014). Lay providers can deliver effective cognitive behavior therapy for older adults with generalized anxiety disorder: A randomized trial. Depression and Anxiety, 31(5), 391–401. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22239

- Thomas, B. H., Ciliska, D., Dobbins, M., & Micucci, S. (2004). A process for systematically reviewing the literature: Providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 1(3), 176–184. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-475X.2004.04006.x

- Unruh, M. L., Redline, S., An, M.-W., Buysse, D. J., Nieto, F. J., Yeh, J.-L., & Newman, A. B. (2008). Subjective and objective sleep quality and aging in the sleep heart health study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 56(7), 1218–1227. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01755.x

- Yaffe, K., Falvey, C. M., & Hoang, T. (2014). Connections between sleep and cognition in older adults. The Lancet Neurology, 13(10), 1017–1028. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70172-3

- Yesavage, J. A. (1988). Geriatric depression scale. Psychopharmacol Bulletin, 24(4), 709–711.