?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This study examines the key influencing factors of voluntary dual ratings selection in corporate bond financing and the effect of dual ratings on risk premium and default risk, based on corporate bond data issued from 2016 to 2021. It shows that the worse the bond issuers’ credit qualifications, the more likely they are to seek dual ratings before issuance. Compared to a single credit rating, the risk premium for a bond with dual ratings is lower, and the effect becomes more significant in the low-rated and non-listed company samples. There are dual ratings before bond issuance, and the higher the average credit rating level of the bond, the lower the bond’s default risk. The research findings provide a theoretical basis and empirical evidence for the practice of voluntary dual ratings in China, expand research on the influencing mechanism of bond issuance pricing in the context of voluntary dual ratings selection, and examine the information content of credit ratings from the perspective of their ability to predict bond default.

JEL CLASSIFICATION:

1. Introduction

In March 2021, the Outline of the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021–2025) for National Economic and Social Development and Vision 2035 of the People’s Republic of China emphasized “Increasing the proportion of direct financing and steadily expanding the bond market.”Footnote1 As the Chinese bond market grew to become the world’s second-largest, the scale of corporate bond financing is growing rapidly. The outstanding size of corporate bonds stood at approximately 10 trillion yuan by 2021, and the number of bonds exceeded 10,000, providing support for expanding direct financing and serving the real economy. Corporate bonds have gradually become the focus of theoretical, practical, and regulatory fields.

With the rapid development of the Chinese bond market, calls to improve credit rating quality have increased. Credit ratings play a role in revealing the credit risk of the evaluated issuer or bond in the bond market, thus affecting investors’ decision-making and issuers’ financing costs. However, there are numerous problems with credit ratings in the Chinese bond market, such as rating inflation, the low discrimination of credit ratings, and a lag in rating adjustment. At the end of 2020, the AAA-rated Brilliance Auto and Yongmei groups defaulted successively, and the credibility of credit rating agencies was widely questioned. Therefore, learning from international experience and introducing dual ratings may be a way to resolve current issues.

Dual ratings refer to two credit rating agencies that simultaneously rate bond issuers or bonds, and independently publish rating results during the bond issuance process. First, dual ratings enable mutual validation of rating results, promote credit rating agencies improving their rating capabilities through reputation incentives and restraint mechanisms, and enhance the accuracy and timeliness of credit rating results, a market-oriented measure to inhibit vicious bond market competition. Second, dual ratings enrich investors’ choices of information and reduce information asymmetry. Under dual ratings, different credit rating agencies rate the same issuer or bond and disclose the rating results to the public so that investors can obtain more information, which helps improve asset allocation efficiency. Third, dual ratings can help optimize rating industry supervision. Regulators can consider gradually weakening the restrictions on the threshold of bond issuance level with the help of a dual-rating model, revealing and controlling bond market credit risk through a market-based restraint mechanism, reducing the adverse selection problem, and improving the credibility of rating results. In the long-term market practices of bond markets in the United States and developed European countries, a dual-rating model has been generated and used in bond issuance and investment processes. China has also attempted to adopt the dual-rating model: After the restart of China’s credit asset-backed securities in May 2012, owing to their complex structure and high-risk characteristics, the Notice on the Further Expansion of the Credit Asset-Backed Securitization Pilot issued by People’s Bank of China and other two ministries required asset-backed securities to adopt dual ratings for improving rating accuracy and strengthening credit risk revealment and prevention functions Footnote2. In January 2013, the Self-Discipline Guidelines for Debt Financing Instruments of Non-Financial Enterprises issued by the National Association of Financial Market Institutional Investors of China proposed to give full play to the role of credit rating risk disclosure and encourage the implementation of a dual-rating model, advocating the simultaneous rating of the same rated object by credit rating agencies that rank high in market-based evaluations or have different pay models Footnote3. In August 2021, the Notice on Promoting the Healthy Development of the Credit Rating Industry in the Bond Market issued by five ministries of China encouraged issuers to select two or more credit rating agencies to conduct rating businesses and play the cross-validation role of dual ratings and multiple ratings Footnote4.

On the one hand, mutual validation provides quality assurance for rating results. On the other hand, credit rating agencies will also enhance rating tracking and improve rating accuracy out of competition. China has not yet fully implemented a dual-rating model, and has only started the dual ratings pilot in asset-backed securities and super-and short-term commercial papers. There are no mandatory requirements for dual ratings in the Chinese corporate bond market. Corporate bond issuers spontaneously select dual ratings to improve information disclosure, increase investor recognition, and lower financing costs.

This study examines the impact of issuers’ credit qualifications on the selection of dual ratings and the information value of voluntary dual ratings, that is, the impact on bond pricing and default warning – using a sample of corporate bonds issued from 2016 to 2021. We group the sample to examine the effect of bond issuer heterogeneity on the pricing effect of dual ratings. In addition, we examine the default prediction ability of the average credit rating level under dual ratings, combined with the default status of the corporate bond market.

The main contributions of this study are as follows. First, it provides empirical evidence for the practice of the dual-rating model in China, an emerging market. Currently, most literature focuses on the economic role played by dual-rating models in the European and US bond markets (Baker and Mansi Citation2002; Bongaerts, Cremers, and Goetzmann Citation2012; Chen and Wang Citation2021; Drago and Gallo Citation2018), but few studies focus on credit ratings in the Chinese bond market. Our study enriches this research field. Second, it expands the research on the influencing mechanism of bond issuance pricing. Many studies (Cornaggia, Cornaggia, and Israelsen Citation2018; Ederington, Yawitz, and Roberts Citation1987; Kisgen and Strahan Citation2010; Livingston, Poon, and Zhou Citation2018; Poon and Chan Citation2008) examine the relationship between single credit rating and risk premium, but few studies examine the impact of dual ratings on risk premium. Third, scholars often focus on the impact of credit ratings on bond pricing and pay less attention to the early warnings of bond defaults. With the gradual break of “Rigid Redemption” and the continuous regulatory system improvement, events of default in the Chinese bond market have increased significantly, and default risks have expanded sharply. It is of great practical significance to examine the information content of credit ratings from the perspective of their (credit ratings’) ability to predict bond defaults and to study whether credit ratings under the dual-rating model can effectively predict bond defaults and provide an early warning of a default. Fourth, from the perspective of practical significance, this study examines the link between the credit qualification of the bond issuer and the selection of voluntary dual ratings through empirical analysis; it tests the information value of voluntary dual ratings, that is, the impact on bond issuance pricing and the impact of default warning. This helps investors focus credit ratings and reduce investment risk. Moreover, this study helps bond issuers attach importance to companies’ credit qualification and further alleviates the potential information asymmetry in the corporate bond market, thus reducing the corporate bond risk premium. Finally, it helps the regulator provide active guidance and introduce policies to encourage dual ratings, which can improve the information quality of the Chinese credit rating market and promote healthy development of the Chinese bond market.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews relevant studies; Section 3 develops the research hypotheses; Section 4 introduces the data and models; Section 5 reports and analyzes the empirical results; and Section 6 concludes the study and provides suggestions.

2. Literature Review

Hsueh and Kidwell (Citation1988) reported that issuers may need more than one rating to reduce information asymmetry and obtain additional information, thus reducing financing costs. Baker and Mansi (Citation2002) find that the expectations of investors and issuers for credit ratings are inconsistent, and issuers seek more credit rating agencies than institutional investors. Further, Bongaerts, Cremers, and Goetzmann (Citation2012) analyzed three theories of multiple ratings – information production, rating shopping, and regulatory certification – using inconsistencies in rating composition, default prediction, and credit spread to prove that the issuer’s selection of multiple credit rating agencies is most consistent with the certification demands of regulatory and rule-based constraints. Sangiorgi and Spatt (Citation2017) reported that if the benefits of additional ratings exceed the costs of information production, multiple ratings are socially optimal. Ryoo, Lee, and Jeon (Citation2021) argued that additional credit ratings can generate more information and improve rating credibility, thus, having a higher certification effect. Chen and Wang (Citation2021) used the Lehman index rule change in 2005 to find that companies hedge against downgrade risk by seeking a third rating from Fitch.

Regarding studies in the Chinese bond market, Xu and Chen (Citation2008) were the first to suggest that, to control vicious competition and regulate the rating industry’s orderly development, a dual-rating model should be introduced into the Chinese bond market concerning international practice. Based on theoretical analysis, international experience, and the actual situation in China, Guo (Citation2013) developed ideas on institutional arrangement, qualification recognition, and implementation scope for the implementation of dual ratings in China. Chen, Lian, and Zhu (Citation2021) verified the information production and credit certification mechanism of multiple credit ratings using empirical analysis and examined the effect of voluntary and mandatory multiple credit ratings on bond financing costs. They found that voluntary multiple credit ratings do not significantly reduce bond financing costs. Using the panel ordered logit model, Zhou and Böckerman (Citation2021) found that credit rating agencies provide more stringent rating upgrades, stronger regulation effectiveness, higher levels of effort to provide more rating information, and a lower probability of rating defaults under dual ratings.

The Chinese bond market has experienced changes in both the political and economic environments, which requires further research based on new market development trends. The selection of dual ratings and information value must be further explored and verified. We complement the existing studies on dual ratings in China, especially in the field of voluntary dual ratings. First, most current studies on dual ratings remain at the theoretical level, and there are few empirical studies on dual ratings in the Chinese bond market. This study uses Chinese bond market data to analyze the causal relationships between the main variables related to voluntary dual ratings. Second, compared to other studies on the relationship between dual ratings and risk premiums in the Chinese bond market, this study has a different research focus. Our study focuses on corporate bond risk premium and default based on voluntary dual ratings selection. Specifically, we verify that issuers’ credit qualifications influence the choice of voluntary dual ratings, and we verify that voluntary dual ratings significantly reduce the corporate bond risk premium, which is more significant in the low-rated and non-listed company samples. We verify that the higher the average credit rating level of a bond with voluntary dual ratings before bond issuance, the lower the default risk of the bonds. Third, Chen, Lian, and Zhu (Citation2021) included issuance data for four types of bonds: commercial papers, medium-term notes, enterprise bonds, and corporate bonds. The dual rating sample of their study included mandatory dual ratings and voluntary dual ratings. This study focuses on corporate bonds with a high degree of marketization in the Chinese bond market (Hong Citation2020), and the dual rating sample is limited to voluntary dual ratings. Companies issue corporate bonds, which are essential tools for obtaining direct financing in the capital market. The Chinese corporate bond market has experienced rapid development over the past decade with the continuous expansion of bond varieties and market scale. In January 2015, the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) released the Measures for Administration of Issuance and Trading of Corporate BondsFootnote5, which lowered the threshold for issuing corporate bonds. The enthusiasm for issuing corporate bonds increased and the corporate bond market expanded rapidly. With the deepening of the bond market reform, corporate bonds have gradually become the focus of attention in theoretical and practical circles. Fourth, existing studies on dual ratings in the Chinese bond market (mainly refer to Chen, Lian, and Zhu (Citation2021)) selected a sample period that focuses on the years before March 2018, while our study expands the sample period to 2021 and mainly focused on the years after 2018 (91.73%). The reasons for selecting the sample in this study are as follows: On the one hand, since 2018, the Chinese bond market size has dramatically expanded. By the end of 2017, the outstanding size of bonds was 74.77 trillion yuan, and by the end of 2021, the outstanding size of bonds stood at approximately 130.35 trillion yuan, an increase of 74.33%. On the other hand, in 2018, the National Association of Financial Market Institutional Investors (NAFMII) and Insurance Asset Management Association of China (IAMAC) successively developed self-regulatory rules for credit rating agencies to strengthen the self-regulatory management of the rating industry. The China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) and the National Association of Financial Market Institutional Investors (NAFMII) conducted joint on-site inspections of credit rating agencies for the first time and imposed the strongest penalty ever; credit rating agencies are facing tightened regulations. Finally, since 2018, the number of bond defaults in China has exceeded 100-billion-yuan, events of default are increasingly normalized and structural. Bond defaults have a significant impact on risk premiums and defaults. The arrival of the default wave also enables the study to directly use actual bond default data to examine default risks and test the credit rating information content from the perspective of their ability for default prediction.

3. Hypothesis Development

In the credit bond market, credit rating – a comprehensive assessment of solvency by professional institutions through scientific methods – has been established owing to the obstacles investors face in assessing issuers’ credit qualifications. Credit ratings play an important role in providing security for issuers’ financing and as a basis for investors’ decision-making. Assessments from independent credit rating agencies facilitate the communication of helpful information to the external market (Agoraki, Gounopoulos, and Kouretas Citation2021). Although credit rating is considered an accurate and credible information signal, the cliff-like decline in corporate ratings after the default of high-rated credit bonds such as Brilliance and Yongmei has raised doubts about credit ratings’ objectivity and validity. In fact, in addition to China, the three major credit rating agencies in the United States have suffered severe reputational damage for misleading investors in the 2008 subprime crisis (Huang, Svec, and Wu Citation2021). The lack of trust in the rating industry may be due to bond issuers being the primary source of revenue for credit rating agencies. Moreover, credit rating agencies only earn revenue when issuers adopt the ratings given by the agencies, thus giving credit rating agencies an incentive to give inflated credit ratings in a highly competitive rating market (Drago and Gallo Citation2018). On the regulatory side, bond issuance generally requires a certain credit rating, and some countries require financial institutions to invest only in investment-grade bonds (i.e., BBB and above) but not in speculative-grade bonds (i.e., below BBB), which also has an impact on credit ratings quality. However, some scholars, such as Bolton, Freixas, and Shapiro (Citation2012), argued that bond market investors are experienced and aware of the conflicts of interest between credit rating agencies and bond issuers.

3.1. Credit Qualification and Voluntary Dual Ratings Selection

Dual ratings have both information and reputation constraint effects: The information effect signifies those dual ratings can provide investors with incremental information, reduce the transaction costs of collecting information, reduce information asymmetry between issuers and investors, play a price discovery function, and improve resource allocation efficiency. Under dual ratings, if the credit rating levels are consistent, they can play the role of double confirmation, and investors agree more with the rating results. If credit rating levels are split, investors can have more rating results for reference and can obtain a more objective and comprehensive understanding of the issuer’s risk and investigate the information related to higher ratings; thus, dual ratings have a positive comprehensive effect on companies. Regarding the reputation constraint effect, Shapiro (Citation1983) argues that reputation mechanisms can restrain sellers’ behaviors and prompt them to improve their quality. In terms of credit rating, Standard & Poor’s statement on credit rating agencies states that the value of the credit rating business depends entirely on the market’s confidence in the credibility and reliability of their credit ratingsFootnote6. Becker and Milbourn (Citation2008) argued that the provision of high-quality ratings is at least partly underpinned by the reputation of credit rating agencies.

On the one hand, introducing dual ratings can promote mutual validation of rating information from different credit rating agencies, provide incremental information from different dimensions, and reduce the uncertainty of investor decision-making. On the other hand, the reputation restraint mechanism restrains the conflict-of-interest behaviors of credit rating agencies and helps improve rating quality.

Therefore, issuers with greater prior uncertainty are expected to be more likely to seek additional ratings because the potential reduction in uncertainty is the greatest for these issuers. Companies with poor credit qualifications tend to have low ratings, increased credit risk, and serious information asymmetry problems before issuance. To reduce the information asymmetry investors face, bond issuers expect investors to pay attention to higher credit ratings simultaneously and seek voluntary dual ratings more often. Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1.

The worse the bond issuers’ credit qualifications, the more likely they are to seek voluntary dual ratings before issuing bonds.

3.2. Dual Ratings and Risk Premium

Fulghieri, Strobl, and Xia (Citation2013) find that credit rating agencies can obtain private information that investors cannot obtain through their professional knowledge in assessing the credit risks of companies to make better estimates of corporate defaults and recovery rates. Most credit rating agencies provide credit ratings for companies and individual financial products that have been issued and add their services by publishing rating outlooks and reviews, which can indicate future changes in credit ratings and are useful uncertainty-mitigation mechanisms (Goergen, Gounopoulos, and Koutroumpis Citation2021).

Corporate management actively seeks ways to convey a company’s intrinsic value to reduce the heterogeneity of investor valuations (Chemmanur and Paeglis Citation2005). Obtaining dual ratings significantly enhances external investors’ trust in the company. In oligopolistic rating markets, companies with only one rating are less attractive to investors than companies with multiple ratings, and investors have higher recognition of companies with dual ratings.

Risk compensation theory suggests that investors facing risk can obtain price compensation for risk taking by increasing risk returns. The dual-rating model plays a major role in reducing information asymmetry, improving bond market transparency, and reducing investors’ information-searching costs. Although dual ratings incur incremental rating costs, investors also tend to believe that companies with dual ratings have lower investment risk, which helps reduce the difficulties of bond issuance and thus lowers the overall financing costs. Accordingly, we propose the following hypotheses:

H2.

The dual ratings of the bond issuers help reduce risk premiums.

Financial markets are characterized by information asymmetry. By issuing credit ratings, credit rating agencies can reduce the information asymmetry between companies and investors (Fulghieri, Strobl, and Xia Citation2013). The utility of proprietary information for ratings is higher when the degree of information asymmetry is high. A lower credit rating implies higher performance uncertainty, expected default risk, and information asymmetry. Dual ratings can reduce the degree of information asymmetry by transmitting market signals. Thus, in low-rated samples, the incremental information provided by dual ratings is more useful than that provided by high-rated samples and the potential effect of reducing information asymmetry is greater. The information effect of dual ratings is more significant for low-rated bonds than for high-rated bonds. Thus, dual ratings have a stronger effect on reducing the risk premium of corporate bonds. Accordingly, we propose the following hypotheses:

H2a.

Compared to high-rated bond issuers, the effect of dual ratings in reducing bond risk premiums is greater for low-rated bond issuers.

Issuers of Chinese corporate bonds include both listed and non-listed companies. Compared to non-listed companies, listed companies tend to disclose more adequate information. First, listed companies must voluntarily disclose more information for financing and social responsibility. Investors can obtain information through channels such as news media and research reports, thereby reducing the costs of information searching and credit screening. Second, regulators have stricter information disclosure requirements for listed companies, whereas non-listed companies have insufficient information disclosure and face more serious information asymmetry. Based on the above analysis, when the issuer is a non-listed company, the deterioration of the information environment causes investors to face a higher degree of information asymmetry, and pay more attention to credit rating information, which enhances the effect of dual ratings on the risk premium. Therefore, there should be differences in dual ratings’ effects on reducing risk premiums in different information environments. This leads to the following hypothesis.

H2b.

Compared to listed bond issuers, the effect of dual ratings in reducing bond risk premiums is greater for non-listed bond issuers.

3.3. Dual Ratings and Bond Default

Considering the global economic recession, the number of bond defaults increased significantly. The successive defaults of high-rated and state-owned enterprise bonds have exposed the problem of weak credit rating default-warning ability. In August 2021, the Notice on Promoting the Healthy Development of the Credit Rating Industry in the Bond Market issued by the People’s Bank of China and four other ministries proposed that credit rating agencies should build a rating quality validation mechanism centered on the default rate4. Attaching importance to the default rate of each credit rating level improves the credibility and reference value of credit ratings.

In the Chinese bond market, the increasing number and amount of defaulted bonds creates conditions for examining default risk using real events of default and directly testing the information content of credit ratings from the perspective of their default predictive ability. Cross-validation, information production, and reputation constraint mechanisms of dual ratings ensure rating quality. Because dual ratings can effectively alleviate the degree of information asymmetry between issuers and investors, the average credit rating level of dual ratings should be more effective in predicting default risk. This leads to the following hypothesis.

H3.

The higher the average credit rating level of a bond with dual ratings before bond issuance, the lower the default risk of bonds.

4. Data and Methods

4.1. Sample Selection

2016 was the opening year of China’s 13th Five-Year Plan and the key year of the Supply-side Structural Reform, during which the “Three Go, One Drop, One Supplement Policy” (capacity reduction, de-stocking, deleveraging, cost reduction, and improving underdeveloped areas) was fully promoted in China, and defaults in the bond market gradually became normalized. Therefore, corporate bond issuance data in the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchange markets from 2016 to 2021 in China are selected as the initial sample, and the following observations are excluded: (1) the issuer belongs to the financial or insurance industry; (2) the issuer is not in mainland China; (3) the bond issuance fails; (4) the coupon rate at issuance is missing or corporate credit rating is missing; and (5) the corporate financial data are missing. Finally, 4315 observations are obtained. Continuous variables are winsorized at the 1% level in both distribution tails to eliminate the effect of outliers. Government bond yield data are obtained from China Bond. Corporate bond issuance data, credit rating data, financial data of debt issuers, and other control variables are obtained from the Wind-Financial Terminal. We use SPSS 19 and Stata15.1 software for econometric analysis. Standard errors are clustered by firm to account for multiple bond issues made by them.

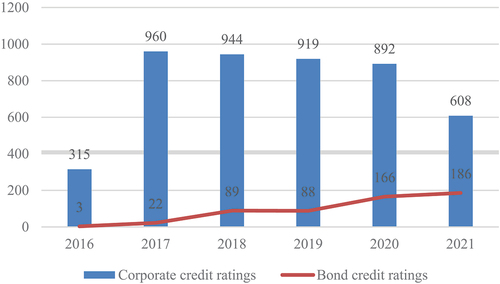

The number of corporate bonds with voluntary dual ratings in the sample has been rising during the four years, from 2016 to 2019, were 6, 33, 55, and 91, respectively, and the number of voluntary dual-rated bonds fell to 52 in 2020, probably owing to the impact of the coronavirus-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on the bond market. However, after the spread of the pandemic was controlled in 2021, the number of voluntary dual-rated bonds rose to 98. Overall, voluntary dual-rated bonds show a growing annual trend in the sample period. Driven by both the spontaneous force of the bond market and the guiding force at the regulatory level, the increase in the number of voluntary dual ratings in recent years confirms, to a certain extent, the issuer’s response to the policy.

4.2. Variables and Model Design

4.2.1. Key Variables Definition

4.2.1.1. Dual ratings (Dual)

Dual ratings are defined as bonds that have obtained credit ratings from two or more credit rating agencies within one month before issuance, and very few bonds in the sample are greater than or equal to three credit rating agencies. Dual is equal to 1 if the bond meets this condition and 0 otherwise. At present, most dual ratings or multiple ratings for corporations in China are carried out when the same company issues different bonds at different times, which has the problems of incomplete rating information and poor comparability between rating results.

It should be noted that since the rating period usually takes about 20 working days from the signing of the rating commission agreement to the final publication of the credit rating report, obtaining a second credit rating, in most cases, is not an action made after the release of the first credit rating. The time interval between the release of the two credit ratings is short; therefore, it can be considered that the dual ratings are issued almost simultaneously.

4.2.1.2. Risk Premium (Spread)

We use the credit spread to measure the risk premium. The credit spread is the difference between the coupon rate at issuance and the yield of government bonds with the same maturity at issuance. When the government bond yield of the corresponding maturity is missing, the linear interpolation method is used.

4.2.1.3. Credit Rating (Rating)

According to the time-series analysis of credit ratings updates during the sample period (), we find that corporate credit ratings are updated more frequently than bond credit ratings, indicating that both bond market investors and regulators pay more attention to the credit qualification and default risk of bond issuers. Changes in a corporation’s basic operation, financial status, and risk resistance have a greater influence on the future solvency and default risk of the bond. Therefore, corporate credit ratings are selected as a proxy for credit ratings. The assignment ideas are as follows: a value of 6 is assigned for AAA ratings, 5 for AAA-, 4 for AA+, 3 for AA, 2 for AA, and 1 for A+ and below. If split ratings exist on dual-rated bonds, the credit rating levels are inconsistent using the average rating level.

4.2.1.4. Default Risk (Default)

The dummy variable Default is used as the dependent variable, which equals 1 if the bond defaults within three years after issuance, and 0 otherwise.

The control variables include the issuer and bond characteristics. Issuer characteristics include company size (Lnasset), leverage ratio (Lev), return on equity (Roe), current asset ratio (Curasset), revenue growth rate (Growth), interest coverage ratio (Ebitint), credit rating (Rating), listing status (List), state-owned enterprises (Soe), and province (Prov). Bond characteristics include bond maturity (Maturity), issuance scale (Lnscale), and the underwriter (Underw). The other control variables include the year and industry dummy variables. The issuer characteristic variables are lagged by one period to mitigate endogeneity issues. presents the names and definitions of the variables are shown in .

Table 1. Variable definitions.

4.2.2. Model Design

The following logistic model is constructed to examine H1 according to theoretical analysis and variable definitions:

To examine H2, H2a, and H2b, we examine the effect of bond issuers heterogeneity on the pricing effect of dual ratings. First, the previous research sample is divided into high-rated and low-rated groups. The sample is divided into listed and non-listed groups. Observations with AAA- and AAA-level credit ratings are in the high-rated group; otherwise, they are in the low-rated group. The following ordinary least squares (OLS) regression model is constructed:

The following logistic model is constructed to examine H3.

5. Empirical Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

reports the descriptive statistics for the main variables. The mean value of Dual is 0.0776, indicating that two or more credit rating agencies gave nearly 8% of corporate bonds credit ratings within one month before issuance (335 observations, of which 310 observations (92.54%) have two credit rating agencies and 25 observations (7.46%) have greater than or equal to three credit rating agencies). The mean value of Spread is 2.0486, indicating that the coupon rate at issuance is 2.05% higher than the government bond yield. The mean value of Rating is 4.5632, indicating that more than half of the corporate bonds are rated higher than AA+ and are AAA and AAA-rated. The mean value of Default is 0.0250, indicating that 2.5% of the corporate bonds (108 observations) default within three years after issuance. The mean value of List is 0.1497, indicating that the sample companies are mainly non-listed.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics.

5.2. Regression Analyses

5.2.1. Effect of Credit Qualification on the Probability of Seeking Voluntary Dual Ratings

Column (1) of presents the logistic regression results for H1 the effect of credit qualification on the probability of seeking voluntary dual ratings. The table shows that after controlling for other financial indicators and year- and industry-fixed effects, the coefficient of Rating is −0.0501, which is significantly negative at the 1% level. Since the credit rating is a comprehensive indicator of the bond issuer’s credit qualification, the worse the credit qualification, the lower the corporate credit rating. The significantly negative coefficient of Rating indicates that the lower the credit rating, the higher the probability of seeking dual ratings before issuance compared to choosing only one credit rating agency. H1 is verified.

Table 3. Effect of credit qualification on the probability of seeking voluntary dual ratings.

5.2.2. Effect of Dual Ratings on Risk Premium

Column (1) of reports the OLS regression results for examining H2 the effect of dual ratings on risk premium; columns (2) and (3) of report the results for examining H2a, the effect of dual ratings on the risk premium of high- and low-rated groups; and columns (4) and (5) of report the results for examining H2b, the effect of dual ratings on the risk premium of listed and non-listed company groups.

Table 4. Effect of dual ratings on risk premium.

According to column (1) of , after controlling for other financial indicators and year- and industry-fixed effects, the coefficient of Dual is −0.2594, which is significantly negative at the 1% level. This result indicates that bonds with dual ratings have a lower risk premium than bonds with a single credit rating. The relationship between incremental credit rating costs and the reduction in risk premium cannot be directly measured based on public information on the Chinese bond market. The empirical study of a limited sample, comparing and analyzing dual and single ratings, confirms that dual ratings significantly reduce comprehensive debt financing costs, which is consistent with H2.

Columns (2) and (3) of show that in the low-rated sample group, Dual has a negative impact on Spread, with a regression coefficient of −0.2043, which is significant at the 1% level. In the high-rated bond issuer group, Dual has no significant impact on Spread. This result indicates that the incremental information provided by dual ratings is more useful and has a stronger effect on reducing information asymmetry in the low-rated bond issuer group; the information and reputation constraint effects of dual ratings are more significant than those of high-rated bonds, thus having a lower risk premium. Consequently, H2a is verified and the conclusion that the effect is stronger in the low-rated group is logically consistent with H1. Fisher’s permutation test is used to examine the difference in coefficients between high- and low-rated groups to examine the robustness of the results. The results show that the difference in coefficients between groups for Dual is 0.1860 and significant at the 1% level, indicating that the results between the two groups are significantly different.

Columns (4) and (5) of show that in the sample group of non-listed companies, Dual has a significant negative impact on Spread, with a regression coefficient of −0.2747, which is significant at the 1% level. By contrast, Dual has no significant impact on Spread in the sample group of listed companies. This indicates that dual ratings have a stronger effect on reducing information asymmetry and lower risk premium for non-listed companies. The difference in coefficients between the groups is significant at the 10% level. Thus, H2b is verified.

5.2.3. Effect of Dual Ratings on Bond Default

reports the logistic regression results for examining H3, the effect of dual ratings on bond default. After controlling for other financial indicators as well as the year and industry fixed effects, the coefficient of Dual×Rating is −0.0159, which is significantly negative at the 5% level. This indicates that the higher the average credit rating level of a bond with dual ratings before bond issuance, the lower the probability of future default and the lower the expected default risk of the bond. The average credit rating level can more accurately predict future default risk when the bond has dual ratings. H3 is verified.

Table 5. Effect of dual ratings on bond default.

5.3. Robustness Tests

5.3.1. Endogeneity Issues

5.3.1.1. Propensity Score Matching

To reduce the effects of selection bias, Propensity Score Matching (PSM) is used to examine H2, H2a and H2b. Specifically, we use the Nearest Neighbor Matching method and matching at 1:1, controlling for Lnasset, Lev, Roe, Growth, Rating, and Soe variables as well as the year and industry dummy variables, to ensure that the control group is as similar as possible to the treated group regarding observable characteristics.

Panel A of reports the PSM results. The average treatment effect on the treated (ATT) is 0.2870 and significant at the 1% level. As the standard errors reported in Panel A do not consider the fact that the propensity score is estimated, the alternative hypothesis of homoscedasticity for these standard errors may also not hold. We use the Bootstrap method to estimate the standard errors. Panel B of reports a Bootstrap standard error of 0.1215 for ATT and it is significant at the 1% level, indicating that H2, H2a and H2b are robust.

Table 6. Propensity score matching.

5.3.1.2. Compare Means Test

There are 335 dual-rated bonds in the sample, of which 216 are split ratings. The Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test, a nonparametric test, is used to compare the differences between the two rating levels in the dual ratings. presents the results of comparing the two rating levels in the dual ratings, where Rating1 is the earlier published rating level of the dual ratings, and Rating2 is the latter. From Panel A’s descriptive statistics, the mean value of the earlier rating is 4.0716 and the mean value of the later rating is 3.5970. The p-value is 0.0000, which is less than 0.05, indicating that a significant difference exists between the two rating levels for dual ratings. On the one hand, the earlier rating is significantly higher than the later rating. On the other hand, it reflects that the selection of dual ratings is not due to rating shopping, and there is no obvious rating inflation in dual-rated bonds.

Table 7. Two rating levels in dual ratings.

5.3.2. Excluding Observations with Three or More Ratings

We exclude observations greater than or equal to the three credit rating agencies before issuance. Observations with three or more ratings (25 observations, accounting for 7.46%) are excluded from the robustness check, and observations with two rating agencies are defined as dual ratings. The research conclusions remain unchanged. The results are omitted because of space limitations.

5.3.3. Excluding the Impact of COVID-19

5.3.3.1. Excluding the 2020 Observations

The outbreak and rapid spread of the COVID-19 pandemic have had a significant impact on the Chinese economy. To exclude the adverse impact of the pandemic on the Chinese bond market, observations from 2020 are excluded for a robustness check. The results are omitted because of space limitations.

5.3.3.2. Excluding “the Special Debt for Pandemic Prevention and Control” Observations

To prevent and control the pandemic and strengthen financial support, Chinese regulatory authorities have provided a “green channel” for bond issuance; “the Special Debt for Pandemic Prevention and Control” was established. Excluding special debt observations in the regression analysis does not change the conclusions. The results are omitted because of space limitations.

5.3.4. Changing the Measurement of Key Variables

5.3.4.1. Changing the Measurement of Credit Rating

We use a new variable, High- rating, for credit ratings. High-rating equals 1 if the bond is AAA or AAA-rated and 0 if the bond is rated below AAA-. Using Model (1) for logistic regression, the results are shown in Column (2) of .

5.3.4.2. Changing the Measurement of Risk Premium

We use the coupon rate at issuance (Rate) as the dependent variable and control for the government bond yield at the same maturity at issuance (Rf). Using Model (2) for OLS regression, the results are shown in .

Table 8. Robustness tests.

5.3.4.3. Change the measurement of default risk

The new variable Default1 for default risk is set. Default1 equals 1 if the bond defaults after issuance, and 0 otherwise. Using Model (3) for logistic regression, the results are shown in Column (2) of .

The results of the robustness tests are consistent with the conclusions of the above study.

6. Conclusion

Using data on corporate bonds issued from 2016 to 2021 as a sample, we study the effects of corporate credit qualification on voluntary dual ratings selection and that of dual ratings on bond pricing, examining the default prediction ability of the average credit rating level under dual ratings. This study finds that the worse the bond issuers’ credit qualifications, the more likely they are to seek voluntary dual ratings before issuing bonds. Compared with a single credit rating, the risk premium for bonds with dual ratings is lower, and the effect of reducing the risk premium becomes more significant in low-rated and non-listed company samples with a higher degree of information asymmetry. There are dual ratings before bond issuance, and the higher the average credit rating level of the bond, the lower the bond’s default risk; that is, the average credit rating level of the bond with dual ratings can predict the future default risk more accurately.

Based on the findings of this study, we make the following suggestions: First, the dual-rating model should be promoted gradually among bonds with higher risk and higher assessment difficulty, debt collection of small and medium enterprises with higher information asymmetry, and bonds with longer maturity and larger scale. The implementation of a dual-rating model should be encouraged according to the degree of bond market development. Second, credit rating agencies should build a rating quality validation mechanism centered on the default rate and establish a rating system that achieves reasonable discrimination and effectively improves the quality of credit ratings. Finally, the government and relevant regulatory authorities should formulate policies to encourage dual ratings and improve the information quality in the Chinese credit rating industry.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the anonymous referee and editor for their helpful comments and valuable suggestions, which led to important improvements. All errors are of our responsibility. We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.cn) for English language editing.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Xinhua News Agency. 2021. Outline of the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021–2025) for National Economic and Social Development and Vision 2035 of the People’s Republic of China. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-03/13/content_5592681.htm.

2. People’s Bank of China, China Banking Regulatory Commission, Ministry of Finance of the People’s Republic of China. 2012. Notice on the Further Expansion of the Credit Asset-Backed Securitization Pilot. http://www.pbc.gov.cn/tiaofasi/144941/3581332/3586995/index.html.

3. National Association of Financial Market Institutional Investors. 2013. Self-Discipline Guidelines for Debt Financing Instruments of Non-Financial Enterprises. http://nafmii.org.cn/zlgz/hxgll/201301/t20130110_19550.html.

4. People’s Bank of China, National Development and Reform Commission, Ministry of Finance of the People’s Republic of China, China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission, and China Securities Regulatory Commission. 2021. Notice on Promoting the Healthy Development of the Credit Rating Industry in the Bond Market. http://www.pbc.gov.cn/tiaofasi/144941/144979/3941928/4311531/index.html.

5. China Securities Regulatory Commission. 2015. The Measures for Administration of Issuance and Trading of Corporate Bonds. http://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2015/content_2843780.htm.

6. Standard and Poor’s ratings services. 2002. Role and Function of Credit Rating Agencies in the U.S. Securities Markets. https://www.sec.gov/news/extra/credrate/standardpoors.htm.

References

- Agoraki, M. E., D. Gounopoulos, and G. P. Kouretas. 2021. Market expectations and the impact of credit rating on the IPOs of U.S. banks. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 189:587–610. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2021.07.006.

- Baker, H. K., and S. A. Mansi. 2002. Assessing credit rating agencies by bond issuers and institutional investors. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting 29 (9&10):1367–98. doi:10.1111/1468-5957.00474.

- Becker, B., and T. Milbourn. 2008. Reputation and competition: Evidence from the credit rating industry. Harvard Business School Working Papers, 09–051. Harvard Business School.

- Bolton, P., X. Freixas, and J. Shapiro. 2012. The credit ratings game. The Journal of Finance 67 (1):85–111. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.2011.01708.x.

- Bongaerts, D., K. J. M. Cremers, and W. N. Goetzmann. 2012. Tiebreaker: Certification and multiple credit ratings. The Journal of Finance 67 (1):113–52. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.2011.01709.x.

- Chemmanur, T. J., and I. Paeglis. 2005. Management quality, certification, and initial public offerings. Journal of Financial Economics 76 (2):331–68. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2004.10.001.

- Chen, G. T., L. S. Lian, and S. Zhu. 2021. Multiple credit rating and bond financing cost: Evidence from Chinese bond market. Journal of Financial Research 02:94–113.

- Chen, Z. H., and Z. Wang. 2021. Do firms obtain multiple ratings to hedge against downgrade risk? Journal of Banking and Finance 123:106006. doi:10.1016/j.jbankfin.2020.106006.

- Cornaggia, J., K. J. Cornaggia, and R. D. Israelsen. 2018. Credit ratings and the cost of municipal financing. The Review of Financial Studies 31 (6):2038–79. doi:10.1093/rfs/hhx094.

- Drago, D., and R. Gallo. 2018. Do multiple credit ratings affect syndicated loan spreads? Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money 56:1–16. doi:10.1016/j.intfin.2018.04.002.

- Ederington, L. H., J. B. Yawitz, and B. E. Roberts. 1987. The informational content of bond ratings. Journal of Financial Research 10 (3):211–26. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6803.1987.tb00492.x.

- Fulghieri, P., G. Strobl, and H. Xia. 2013. The economics of solicited and unsolicited credit ratings. The Review of Financial Studies 27 (2):484–518. doi:10.1093/rfs/hht072.

- Goergen, M., D. Gounopoulos, and P. Koutroumpis. 2021. Do multiple credit ratings reduce money left on the table? Evidence from U.S. IPOs. Journal of Corporate Finance 67:101898. doi:10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2021.101898.

- Guo, S. P. 2013. The international practice of “dual ratings” system and implications for China. Shanghai Finance 12 (1):141–42.

- Hong, Y. R. 2020. Investor protection under market-based governance of corporation bonds. Journal of Lanzhou University (Social Sciences) 48 (06):69–77.

- Hsueh, L. P., and D. S. Kidwell. 1988. Bond ratings: Are two better than one? Financial Management 17 (1):46–53. doi:10.2307/3665914.

- Huang, H., J. Svec, and E. Wu. 2021. The game changer: Regulatory reform and multiple credit ratings. Journal of Banking & Finance 133:106279. doi:10.1016/j.jbankfin.2021.106279.

- Kisgen, D. J., and P. E. Strahan. 2010. Do regulations based on credit ratings affect a firm’s cost of capital? The Review of Financial Studies 23 (12):4324–47. doi:10.1093/rfs/hhq077.

- Livingston, M., W. P. H. Poon, and L. Zhou. 2018. Are Chinese credit ratings relevant? A study of the Chinese bond market and credit rating industry. Journal of Banking and Finance 87:216–32. doi:10.1016/j.jbankfin.2017.09.020.

- Poon, W. P., and K. C. Chan. 2008. An empirical examination of the informational content of credit ratings in China. Journal of Business Research 61 (7):790–97. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.08.001.

- Ryoo, J., C. Lee, and J. Q. Jeon. 2021. Multiple credit rating: Triple rating under the requirement of dual rating in Korea. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 57 (14):3960–83. doi:10.1080/1540496X.2020.1768071.

- Sangiorgi, F., and C. Spatt. 2017. The economics of credit rating agencies. Foundations and Trends® in Finance 12 (1):1–116. doi:10.1561/0500000048.

- Shapiro, C. 1983. Premiums for high quality products as returns to reputations. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 98 (4):659–79. doi:10.2307/1881782.

- Xu, C. Y., and C. S. Chen. 2008. Chinese bond market credit rating should introduce dual ratings system. Times Finance 06:67–68.

- Zhou, X. Y., and P. Böckerman. 2021. Can the dual-rating regulation improve the rating quality of Chinese corporate bonds? PLoS one 16 (12):e0259759. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0259759.