ABSTRACT

Public concern about “gaslighting” has increased significantly in recent years, both in sociology and the public imagination. As well as describing abuse in romantic relationships, the term has provided a lens for popular understanding of “post-truth” politics. Given that metaphors influence how problems are conceptualized and responded to, we ask how “gaslighting” shapes popular responses to disinformation on Twitter and the conspiracy-rich 4chan. We find that discussions of gaslighting increased significantly on both platforms between 2020–2021, and spiked during the week of the United States 2020 election. We also show that the metaphor can powerfully contest disinformation, while at the same time spread self-sealing and self-fulfilling anxieties about deception that are resistant to disagreement. In light of these findings, we consider how a well designed and well intentioned “good echo chamber” might constitute a technique of resistance to online disinformation.

Introduction

What kind of problem is disinformation? How should we respond to it? In the so-called “post-truth era,” anxieties about deception in politics have come to the fore of the public imagination. But publics have struggled to settle on the concepts and language to interpret it (Simon & Camargo, Citation2021). Given the framing power of language, the metaphors used to describe the problem of disinformation have important consequences for what responses are proposed.

This paper examines an important and overlooked development in this story: the sudden rise of the term “gaslighting” in political debate. An increasingly popular idea in both scholarship and popular culture, gaslighting describes a form of manipulation that causes the victim to doubt their perception of reality. Despite originating in the 1938 play Gas Light, the term only became popular – and a key cultural touchpoint – in the 2010s, when it was reinterpreted as a political metaphor. Particularly since the United States 2016 election, it is now used to depict a range of deceptive behaviors by politicians, most often by Donald Trump, whose post-truth tactics are often compared to an abusive partner. By 2018, the term was shortlisted for the “word of the year” by the Oxford Dictionary (Brockes, Citation2018). What can the emergence of this term tell us about contemporary anxieties about political deception, and resistance to it, in the age of social media?

What is missing from existing accounts of gaslighting is an examination of its use for interpreting and responding to political events. What’s more, attention has yet to be paid to how responses to perceived gaslighting take shape on social media, a key space for contemporary political debate. This paper addresses this gap by examining how the term “gaslighting” is used to debate (and contest) elections on social media. We treat the term “gaslight” as a conceptual metaphor (Lakoff & Johnson, Citation1981) that structures debate in particular ways that shape understanding and response. Recent research on gaslighting suggests that exposing and contesting gaslighting is a tool of resilience and resistance to positions that are disputed and attacked by “official” knowledge. At the same time, we hypothesize that the term may also spread anxieties about truth and judgment, encouraging a self-sealing mentality: like a conspiracy theory (Lewandowsky & Cook, Citation2020), the claim that one is being gaslit is resistant to correction, because contrary evidence can be interpreted as merely another part of the deception. The gaslight metaphor may therefore both protect standpoints that are under attack, while also strengthening conspiratorial echo chambers.

The article studies the role of the gaslighting metaphor in contemporary political discussion culture online by analyzing mentions of the word “gaslighting” in datasets collected from Twitter and 4chan’s /pol/ board during 2–8 November 2020, the week of the United States 2020 presidential election. Twitter and 4chan offer two ideologically and technically contrasting spaces: while Twitter is a mainstream, widely used social media platform that allows posters to publish under their real name, 4chan is an marginal subcultural “imageboard,” most associated with reactionary, right-wing and conspiratorial internet subcultures of “trolls,” “incels” and “the alt-right,” where users post anonymously. Through a combination of close and distant reading, the article represents how the term is variously used in online discussions about election disinformation.

At stake here is how communities use metaphors as framing devices to contest official narratives, and why this particular one, drawn from abuse in romantic relationships, has resonated with contemporary American society. We ask how responses to gaslighting theorized in sociological scholarship, which often involve mutual support and reinforcement known as “echoing,” play out on social media where much public political debate now takes place. In doing so, we wish to complicate current understandings of “echo-chambers” on social media. Although generally understood as a malign distortion of political discussion in the public sphere, we wish (counter-intuitively) to consider how a “good echo-chamber” (Pohlhaus, Citation2020) might also offer protection for “subjugated epistemic standpoints” (Haraway, Citation1988) in online spaces.

Micro – and macro accounts of gaslighting

The term “gaslight” originates from the 1938 play Gas Light, a psychological thriller in which a man manipulates his wife into doubting her perceptions of reality, as part of a plot to commit her to a psychiatric institution. Two decades later, the term “gaslight” first entered psychological literature (Barton & Whitehead, Citation1969), and in that field gained its modern meaning: a conscious or unconscious behavior, enabled by wider contexts of structural power, that causes the victim to doubt their perceptions of reality. However, it has failed to take hold as a credible clinical term, and is now characterized by the American Psychological Association as a colloquialism.

The term remained somewhat dormant in scholarship until 2014, with the publication of Kate Abramson’s paper “Turning Up The Lights On Gaslighting.” Building on the therapeutic understanding of the term, Abrahams sets out an epistemic account of what makes gaslighting immoral. Abramson’s (Citation2014) argument is that the gaslighters’ characteristic desire is “to destroy even the possibility of disagreement,” where the only sure path to that is destroying “the source of possible disagreement … [the] independent, separate, deliberative perspective from which disagreement might arise.” By positioning gaslighting as an epistemic rather than a therapeutic phenomenon, Abramson connects gaslighting to theories of epistemological standpoints: the person who is gaslighted is refused their standpoint because the act “destroy[s] another’s independent perspective” (Citation2014, p. 13). In Haraway’s (Citation1988) account of standpoint epistemology, a major touchstone in feminist theory of how knowledge is constructed and contested, it is particularly “‘subjugated’ standpoints [that] are preferred because they seem to promise more adequate, sustained, objective, transforming accounts of the world.” Following this logic, identifying acts of gaslighting opens up the possibility of protecting valuable, marginalized perspectives. Pohlhaus’s (Citation2020) account of “epistemic gaslighting” similarly connects standpoint epistemology with gaslighting, which she interprets as “oriented not toward psychological breakdown, but rather toward a sort of epistemic breakdown: to put out of circulation a particular way of understanding the world” (677). Pohlhaus’ distinction between the psychological and the epistemic emphasizes that at stake is not just individuals’ suffering, but also alternative ways of knowing and constituting the world, as is a central concern in feminist epistemological standpoint theory (Hartsock, Citation1998).

In an adjacent wave of sociological work on gaslighting, the focus of analysis moves from the micro to the macro by addressing ways that entire communities can be gaslighted. Davis and Ernst (Citation2019), for example, mount an analysis of “racial gaslighting,” which they define as “the political, social, economic and cultural process that perpetuates and normalizes a white supremacist reality through pathologizing those who resist.” Ruíz (Citation2020, p. 689) similarly extends the definition from the interpersonal and the political: her account of “cultural gaslighting” draws attention to “the effort of one culture to undermine another culture’s confidence and stability by causing the victimized collective to doubt [its] own sense and beliefs.” In a similar ilk, Rietdijk (Citation2021) draws on gaslighting as a way to critique tactics of post-truth deception by political leaders who seek to confuse (rather than persuade) their citizens as an instrument of power, mirroring critiques of Russian propaganda (eg Pomerantsev, Citation2019). Broadening analyses of gaslighting from the interpersonal to the societal realm therefore offers a potent tool to critique and contest epistemic power.

However, this literature, which takes a loosely defined form of abuse in romantic relationships to critique different forms of deception at the societal scale, engages in two distinct treatments of the concept. First, there is a claim that gaslighting is always an entanglement between the micro and the macro; that, in Sweet’s (Citation2019, 852) terms, “macro-level social inequalities are transformed into micro-level strategies of abuse.” In other words, there can be no separation between romantic interpersonal abuse and the broader social inequalities and power structures that enable it, thus necessitating a broader social contextualization and analysis. Second, there is the use of gaslighting purely as an evocative metaphor. For example, in Rietdijk’s (Citation2021, p. 11) account of post-truth tactics, by “introducing counternarratives, discrediting critics, and denying facts, politicians can undermine the self-trust of citizens,” which makes this activity is “so very similar to gaslighting.” In our paper, we suggest that gaslighting must be understood in both senses: as a form of epistemic power occurring across micro – and macro scales to disempower already marginalized standpoints with loss of epistemic self-trust, and as a contemporary metaphor for post-truth politics. However, it is the rise of the latter – gaslighting as a popular metaphor – that we focus on in this paper, and to which we now turn.

The rise of the gaslighting metaphor in popular culture

As gaslighting grew to become an increasing focus of philosophical and sociological scholarship, many of the same themes and critiques were reflected – and in some cases anticipated – in popular culture. During the 2010s, gaslighting became an increasingly mainstream term, with magazines such as Psychology Today offering guidance for victims (Ruiz, Citation2020). In 2018, the term was named one of 2018ʹs “buzzwords” by The Guardian (Brockes, Citation2018), and shortlisted for the “word of the year” by the Oxford Dictionary. The sudden increase in cultural interest is indicated by the number of uses of the term in writing during this period ().

Figure 1. A graph showing the number of uses of “gaslighting” in books from 1930–2019.Source: Google Ngram Viewer.

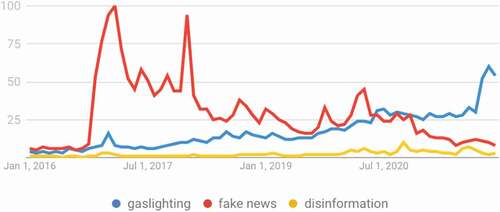

As in scholarship, in popular culture the term was quickly employed as a political metaphor. In an article titled “Donald Trump Is Gaslighting America,” one of the early and most prolific uses of the metaphor was in Teen Vogue (Duca, Citation2016). The author writes that “To gaslight is to psychologically manipulate a person to the point where they question their own sanity, and that’s precisely what Trump is doing to this country.” Though Trump necessarily invokes concerns of interpersonal abuse due to allegations of sexual assault, the use of gaslighting is not deployed to that end. Instead, Duca uses gaslighting to capture a situation at the heart of “post-truth” anxieties: that “facts have become interchangeable with opinions, blinding us into arguing amongst ourselves as our very reality is called into question.” Many articles followed with similar concerns in mainstream publications such as The Washington Post, CNN, The New Yorker, NBC, and USA Today, with headlines such as “Donald Trump is ‘gaslighting’ all of us” (Ghitis, Citation2017). In this framing, Trump is not gaslighting an individual, nor is he trying to deceive the American public into believing a specific false narrative. Instead, the concern is that his tactical use of lies and deception is psychologically manipulating the American public into a confused, self-doubting state that cannot confidently distinguish truthhoods from falsehoods. In this respect, popular concerns with gaslighting as a political tactic aimed at disorientation reflect what’s become known as the “post truth era” (eg d’Ancona, Citation2017) that have arisen during the same time. As such, gaslighting offers an emotive metaphor for popular engagement with concerns about “post-truth” politics. What’s more, it is an increasingly common public concern: by 2020, more people were searching on Google for “gaslighting” than other post-truth keywords, such as “fake news” and “disinformation” ().

Figure 2. The relative number of searches on Google for “gaslighting,” compared to post-truth keywords “fake news,” “disinformation,” and “misinformation.”Source: Google Trends.

In the context of the gaslight metaphor’s rise in popular culture, we propose to treat the term “gaslight” as a conceptual metaphor (Lakoff & Johnson, Citation1981). The term conceptual metaphor accounts for the way metaphors structure debate and thought, highlight some features of a phenomenon and hide others, reflect cultural values, and suggest certain responses. In this understanding, gaslighting is not an arbitrary way of describing political deception, but one that potentially reflects and enacts a particular way of thinking about disinformation, with consequences for which responses are brought forth and which are not.

Gaslighting and echo chambers

What responses are implied by conceptualizing disinformation as gaslighting? Within the scholarship on gaslighting, one answer is simply opting-out of certain sources of information, such as “choosing to limit your news consumption” (Rietdijk, Citation2021). Mirroring this is the proposal for “echoing”: individuals who provide epistemic support by backing up and amplifying the voices of the gaslit (McKinnon, Citation2017). As Pohlhaus notes, such a recommendation clearly calls to mind the much-maligned “echo chamber” theory of political polarization online, which claims that self-selection and algorithmic filtering isolate social media users in hermetically sealed chambers where they are not confronted with contradictory views, leading to polarization and even radicalization (Pariser, Citation2011). However, recent empirical work has suggested that their existence is significantly overstated (Bruns, Citation2019; Dubois & Blank, Citation2018). At the same time, the theory – which normatively assumes them to be a negative distortion of the public sphere – has been brought under question too. For example, (Pohlhaus, Citation2020, p. 682) argues that “survival echoing” can “help one to maintain warranted self-trust and stability of beliefs in the face of unwarranted epistemic pressures to doubt them” – that is, in the face of gaslighting. This leads to the question: what features would make a “good” echo chamber? For Pohlhaus (Citation2020), the answer is the members: whether the people in the echo chamber are “dominantly” or “nondominantly” positioned, and therefore whether the echo chamber resists or reinforces existing epistemic power. However, it is not clear how one would neatly classify individuals’ position of (non)dominance. And even where members were nondominatly positioned, fears about gaslighting may prompt a self-sealing mentality as has been observed in conspiracy theories, where contradictory information is rejected as part of the gaslighting deception. What’s more, literature on epistemic echoing is yet to explore how different social media platforms’ affordances cultivate different kinds of echoing behaviors.

As a result of these empirical and theoretical gaps, an analysis of public discussion about gaslighting, and the echoing behaviors they provoke, offers an opportunity to rethink the echo chamber, and how a “good echo chamber” might contest online disinformation. With these observations in mind, we ask: how was the term “gaslighting” used as a way to discuss disinformation on social media during the United States 2020 election, and what kinds of echoing behaviors did it provoke?

Data and methodology

We examine the use of “gaslighting” on Twitter, a mainstream social media platform, and 4chan, a relatively marginal website. The two platforms offer contrasting discursive spaces. While Twitter allows registered users to post publicly available messages in their real names and in response to public figures, 4chan is an anonymous imageboard to which unregistered users can post. While both sites are renowned for the disputative tone of political discussions, 4chan is notorious as the origin of right-wing and white supremacist conspiracy theories. As such we can be relatively certain of the conspiratorial, right-wing ideological leanings of 4chan, while Twitter can be assumed to include a variety of political opinions. The platforms also share important features. Unlike Facebook, both 4chan and Twitter are characterized by asymmetrical communications in which most users are strangers to one another. Like Twitter, 4chan discussions are threaded under an initial post. In contrast to the frequent use of real names on Twitter, almost all 4chan posts appear with the same “anonymous” handle. 4chan contains 74 thematic discussion forums or “boards,” the most popular of which is /pol/, a notorious site connected to the emergence of the “al-right “ as well as the origins point of the influential “Pizzagate” and “QAnon” conspiracy theories. Due to the sites’ anonymity, as well as the rapid pace and hostile tone of conversation, posters to 4chan/pol/ tend to use both memes and slang expressions to demonstrate their in-group status. These factors have been observed to make 4chan/pol/ as site of “robust vernacular innovation” typically around male and white supremacist ideologies (Peeters, Tuters, & Zeeuw, Citation2021; Zelenkauskaite, Toivanen, Huhtamaki, & Valaskivi, Citation2020). Collectively, hese features result in contrasting spaces for the examination of discussions of gaslighting.

We investigate the uses of the term “gaslighting” on Twitter and 4chan during the United States 2020 presidential election, focusing on the week of 2–8 November, which began with polling day and ended with confirmation of Joe Biden as winner. To test our hypotheses, we adopt a novel approach to analyzing social media, querying data with what we call an “epistemic keyword”: a word that can be used to query online spaces or datasets for epistemic activity that are not specific to one topic. This approach is designed to look beyond individual users, events and topics to instead focus on how certain epistemic activities – in this case, contesting gaslighting – are engaged in large-scale datasets from social media. Epistemic keywords can be understood as a subset of “query design” (Rogers, Citation2017), used to demarcate online “issue spaces” (Rogers, Citation2012). Epistemic keywords offer a tool for identifying a way of thinking (an epistemology) online.

To do this, we first extracted all tweets mentioning gaslighting (with the query “gaslight OR gaslighted OR gaslit OR gaslights OR gaslighting”) between 1 January 2020 and 28 February 2021, using V2 of the Twitter API. We then retrieved tweets specifically related to the election using a second query (“(gaslight OR gaslighted OR gaslit OR gaslights OR gaslighting) AND (vote OR election OR us2020 OR biden OR trump OR democrat OR republican OR democrats OR republicans)”). We then extracted all posts on the 4chan board “/pol/” mentioning gaslighting (with the query “gaslight OR gaslighted OR gaslit OR gaslights OR gaslighting”) via the software tool 4CAT (Peeters & Hagen, CitationIn press).

To examine the use of the term gaslight in these textual corpora, we draw on close and distant reading techniques. We filtered our total corpora for posts published during the week of 2–8 November on Twitter (n = 10,491) and 4chan’s /pol/ board (n = 1,419) respectively. We then conducted a close reading of a random sample of 15% of every day’s set of posts on Twitter to reduce to a manageable size, and every post published on 4chan’s /pol/ board. We combined this close reading with the distant reading technique of “word trees” (Wattenberg & Viégas, Citation2008), which visualize how a target word is followed and/or preceded by other words across many posts, aiding understanding of how the term most commonly features in phrases. We analyzed word trees of words that either involve an interesting relationship to the term “gaslight,” or feature frequently in the corpora. Based on this analysis, we extract broader learnings about how “echoing” is discursively constructed in these online spaces.

Findings and discussion

A growing metaphor

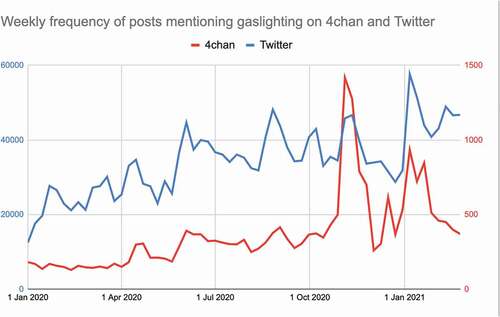

On both Twitter and 4chan’s /pol/ board, gaslighting is an increasingly used term, and directly corresponds to political events, particularly the November 2021 election and January 2021 storming of the Capitol. This indicates that gaslighting is increasingly common in discussions of political events, on both mainstream and alt-right platforms. The prevalence of the term on 4chan indicates that while the term may have originated from a left-wing, social justice position, it has since been adopted, or co-opted, by the alt-right.

On Twitter, we identified 2,102,018 tweets published during this timeframe that mentioned the word gaslight or a variation, and 271,255 tweets (12.9%) that mention gaslighting and at least one keyword related to the election. We find that there is a clear upward trajectory in the use of terms related to gaslighting (). We also observe spikes around key political events: i) the Republican National Convention at the end of August; ii) the election at the beginning of November, and iii) the attack on the Capitol on January 6. These spikes suggest that the most intensive discussion of gaslighting is often in response to political events.

Figure 3. Plot of weekly number of posts containing at least one mention of “gaslighting” (or its variations) from the week of 1 January 2020 to the week of 24 February 2021, on Twitter and 4chan’s /pol/ board.

On 4chan, we identified 55,338 posts mentioning gaslighting since 2013, with a steady and significant increase since 2016. There are two pronounced spikes: the November 2020 election, and the January 2021 storming of the Capitol. We identified 1,419 posts during the week of 2–8 November 2020. As with Twitter, this indicates discussions of gaslighting are both closely connected to political, and specifically electoral, issues, and they flare in reaction to major events.

Twitter: a diverse network of contestation

A close and distant reading of the tweets during 2–8 November 2020 reveal a narrative that Trump and/or the media have gaslighted the United States population. The word “america” occurs 1,413 times, averaging in one in ten of tweets, with a word tree revealing the narrative that it is the victim (). Some tweets explicitly map manipulative romantic abuse onto the relationship between Trump (n = 8,062) and the electorate, describing an “abusive relationship” (n = 32). Others compare him to an ex partner: “like an ex who treated us badly”; “giving me trauma flashbacks to my ex”; “Trump is everyone’s toxic ex that gaslit.” One tweet provides a more elaborated rendition: “MAGA are the gaslighting husband. POC are the abused spouse. POC are not crazy, the racism is real” (POC understood here as “people of color”). These examples make explicit a formulation that is elsewhere implied: Trump or the media is an abuser, and America or marginalized groups are the abused.

The narrative attributes significant psychological power to Trump and the media, and conversely casting citizens as victims of manipulation, emphasizing their vulnerability. Words like “thinking” (n = 223) and “believing” (n = 178) are often invoked to position them as unreliable: one has been gaslit into thinking () or into believing something false. The electorate’s psychology, whether that includes your own or solely your opponents’, is vulnerable and under attack. Not only does this suspend discussions of policies to focus on anxieties about psychological harm, it also infuses debate with a degree of paranoia that could be said to enact the very thing it attempts to expose: making people doubt their perceptions.

One solution to the problems posed by gaslighting is to simply ignore it, and this is a common refrain in the posts. The prevalence word “stop” (n = 1,053), and a word tree of the word “let” (n = 803; ) attest to the call to actions that are common in these posts: to resist by ignoring it. One person tells their followers that Trump, Fox News and the Republican party “are abusive and they will always be wrong. Don’t let them gaslight you.” In messages like these, the accusation of abuse provides an urgent moral case for rejecting information, bolstering self-trust in the face of claims that the election has been stolen. In other cases, people offer messages of emotional support. One tweet reads “sending a virtual hug to all my buddies who are hurting and worrying rn. don’t let the Trump supports gaslight you,” while another says “It just occurred to me how isolating and even gaslighting this election must feel to those who live alone … Sending extra love.” These can be read as examples of “survival echoing” (Pohlhaus, Citation2020, p. 682), which aims to “help one to maintain warranted self-trust and stability of beliefs in the face of unwarranted epistemic pressures to doubt them.” We see in the “stop” and “don’t let” phrases, and supportive messages, how the gaslight metaphor offers a frame for contesting disinformation.

However, in some cases, echoing involves the outright rejection of true information, namely the outcome of the election. Dismissal of true information is often targeted directly at news outlets such as the Wall Street Journal, NPR, and Good Morning America: “@WSJ You and the other fake news do not get to call the election.#gaslighting”; “@NPR Lol. Biden the cheater lost – you’re gaslighting isn’t working”; “@GMA stop gaslighting – this election is not over and you know it.” These messages publicly express resilience in the face of contradictory but true information, with gaslighting used to validate denial and sustain belief in a lie advanced by Donald Trump. Thus, what in some cases may be survival echoing to protect people from Trump’s false “stolen election” narrative, in others are efforts to believe it and reject true information. The gaslight claim is therefore self-sealing, presenting the media’s announcement of Biden’s victory as part of the grand deception.

Though Twitter’s open, weak-tie design is not conducive to the spread of conspiracy theories (Theocharis et al., Citation2021), we nonetheless find that the gaslight metaphor provides a compelling frame for rejecting the outcome of the election by characterizing it as a gaslighting attempt. As we turn to 4chan, we will see how the gaslight metaphor supports even more intensive conspiratorial uses.

4chan: an ambivalent echo chamber

As a historically heavily pro-Trump community, 4chan’s /pol/ board are unsurpisingly in support of Trump’s notorious disinformation campign, which claims the election to have been “stolen” due to “voter fraud”. Posts to 4chan/pol/, which are mostly replies to other users (75%, compared to 16.9% on TwitterFootnote1), often take the form of messages of support and reassurance in the face of Joe Biden being announced winner. This cohesion is characteristic of the site: this in-group cohesion has fed into mass political movements from the hacker group Anonymous to QAnon. This defiant denial is widespread: one post reads “Do not let yourself be gaslit we WILL win”; another “The media will try to gaslight you so they can legitimize their “mail in” ballots. Don’t let them do that to you. Fight.” This often involves explicit rejection of contrary evidence: for example, “i wont be swayed you’re not gaslighting anyone with those fake graphs.” The question of maintaining morale (“demoralisation” is explicitly mentioned 51 times) in the face of growing evidence is a key theme, with the concept of “gaslighting” being critical to that denial and resilient morale. “How are you boys holding up? … Stay level headed, and don’t let the shills suck gaslight you” reads one post; “Dont let the shills gaslight or demoralise you Mail in fraud happened here.” Another post asks the network “Can MSM gaslight you into believing voter fraud?,” inviting a series of defiant responses such as “No. Trump won.,” “nope. Fuck them.” and “No. Fraud was 100% proven.” This call-and-response is reminiscent of public rallies, encouraging vocal declarations of support. As has been noted elsewhere, such discussions strengthen group identity (Hagen & Tuters, Citation2020). Acts of echoing therefore build resilience to contradictory information, in a manner far more pervasive and consistent than observed on Twitter. This demonstrates that “survival echoing” may be an important part of allowing conspiracy theories to emerge and spread because of its self-sealing tendency.

However, despite its morale-boosting messages, /pol/ is nonetheless an anxious environment during election week. Indicative of this climate is that one of the most common words in the dataset is “shills” (n = 501). The Urban Dictionary defines shills as “a person who is pretending to agree with a conspiracy and intentionally circulates false information or acts totally insane in an effort to discredit said conspiracy.” The widespread concern with shills in discussions about gaslighting reflects an anxiety about what kind of space /pol/ is: who is gaslighting, whether anyone can be truly trusted, and how to protect the community from an epistemic threat. One post explicitly draws these themes together: “Everywhere on the popular internet is shitting on trump. The only safe place to publicly talk about the election are chans, and even they’re filled with shills.” 4chan is cast here as a kind of unsafe safe space, ideologically cohesive but under threat from outsiders, and must be maintained, protected, and reassured. One message, posted many times in a kind of chant, reads: “Media and Shills thought they could gaslight /pol/. They have failed.” Others, however, express uncertainty about what to think and how to know: “I dont know whats real, what are fake twitter shitposts, what are actual stats.” Defiant accusations of gaslighting are therefore ambivalent, offering messages of both reassurance and doubt. As observed on Twitter, promoting the presence of gaslighting can be self-fulfilling, contributing to doubt of the community’s ability to decipher what’s real.

Conclusion

In this paper, we have shown that gaslighting is an increasingly common way of understanding electoral disinformation and “post-truth” deception, that its use rises dramatically in response to political events, and that it is common in both mainstream and conspiracy-rich online spaces. Comparing political leaders’ relationship with their publics to abusers’ romantic relationships with their partners vividly casts citizens and electorates as victims in a story of abuse, providing a strong moral case for resistance. And by construing disinformation as a psychological phenomenon, that resistance is not a call for regulation or collective action, but an issue of individual psychology: altering one’s mind-set, boosting others’ morale, and resisting persuasion.

We suggest that this resistance has a tendency toward being self-sealing and self-fulfilling, and therefore can contribute to the problems of trust, polarization and “post-truth” anxieties even as it is used to contest them. The gaslight metaphor is self-sealing because it allows accusers to insulate themselves from correction and dispute. In addition, the gaslight metaphor is also self-fulfilling because it can sow the very doubt in one’s perceptions of reality that it is intended to expose. Any claim of gaslighting is vulnerable to this risk, as it calls for a radical doubt about not only what is true, but how one is forming their judgments about what is true. These qualities help to stimulate the suspicion and isolation that is critical for conspiracy theories, suggesting that echoing may be an important part of how conspiracy theories emerge and spread.

However, the distinct manners in which echoing behaviors unfold on 4chan and Twitter – with 4chan being particularly mutually supportive reflecting its ideological cohesiveness, but also more ambivalently self-sealing and self-fulfilling reflecting its anonymity and high-suspicion culture – indicate that platform affordances may cultivate different kinds of echoing behaviors with different outcomes. And, despite pol’s anti-democratic aims during election week, lessons may nonetheless be learned about survival echoing and the potential for a “good echo chamber.”

A “good echo chamber”

We suggest that debates about gaslighting should encourage researchers to move beyond simplistic moral critiques of “echo chambers,” and instead consider how echo chambers can offer sources of epistemic contestation, as argued by Pohlhaus (Citation2020). We build on this insight by suggesting that echo chambers are strongly influenced by platform cultures (eg ideological leanings), design (eg anonymity), and discursive construction (eg metaphors). “Survival echoing,” we suggest, changes depending on these contexts.

Further exploration of what constitutes a “good echo chamber” is therefore increasingly urgent. Those that contest oppressive regimes may need to participate in self-sealing practices to survive and grow; as Bailey (Citation2020) puts it, “epistemic survival demands the formation of strong resistant epistemic communities.” As a result, “echoing” and accusations of gaslighting increase what Robertson calls the “social group tradition” form of epistemic capital, thereby strengthening the epistemic position of the group. And so, rather than echo chambers being the malign result of platform design, they might in fact constitute a technique of resistance to online disinformation.

But what, then, marks an echo chamber as “good”? For Pohlhaus (Citation2020), the answer is its members: whether they are “dominantly” or “nondominantly” positioned. However, it is not straightforward to classify anonymous users of 4chan as dominant or nondominant given their anonymity. What’s more, clearly it is not just their epistemic location, but their goal (disputing a fair and open election) that is at stake. And, given the role of platform culture, design and discourse in the construction of different kinds of echo chambers, the question of platform governance also comes into view when considering what a “good echo chamber” might look like. And so, rather than asking whether echo chambers do or don’t exist, or how to get rid of them, we might instead ask: what kinds of echo chambers do we want, and how do we create them?

We do not provide answers to these questions, but instead argue that answering them depends on empirically attending to the interaction of platform culture, technical infrastructure, and language. And we have firmly established that this question is ever more urgent, because it is in some sense already being asked by everyday users. It is therefore all the more important that future research into gaslighting attends to how echoing occurs in practice rather than solely in theory. We have shown that investigating debates on social media, with digital methods, can mark a path for this work.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Digital Methods Initiative, and the student participants of the DMI Summer School 2021, for incubating this idea with our project on ‘epistemic keywords.’ This paper would not be possible without the DMI’s positive space for methodological experimentation and fast-paced research projects within the field of digital methods. The idea for this paper was developed with the support of the Digital Methods Initiative’s 2021 Summer School. We’d like to thank the students who helped to explore the concept of ‘epistemic keywords’ that is central to this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tommy Shane

Tommy Shane is a PhD candidate at King’s College London’s Digital Humanities Department. His research focuses on political speech, with a focus on mis- and disinformation, authenticity, and AI. He builds on a background in literary criticism, science and technology studies, and digital methods.

Tom Willaert

Tom Willaert is a researcher in digital methods. Building on a background in humanities scholarship, he develops and uses computational methods for text analysis in order to study societal, cultural and political conflicts in online media. On 1 October 2021, Tom joined VUB’s Brussels School of Governance and Department of Media Studies as a postdoctoral researcher and coordinator of EDMO BELUX, a hub for research on digital media and disinformation. This hub, funded by the European Commission, will gather a network of experts with the aim of responding to harmful disinformation campaigns. For an overview of Tom’s projects and publications, see https://researchportal.vub.be/en/persons/tom-willaert.

Marc Tuters

Marc Tuters is an Assistant Professor in the University of Amsterdam's Media Studies faculty, and a researcher affiliated with the Digital Methods Initiative (DMI) as well as the Open Intelligence Lab (OILab). His current work draws on a mixture of close and distant reading methods to examine how online subcultures use infrastructures and vernaculars to constitute themselves as political movements.

Notes

1. On Twitter, 25% of the tweets from 2–8 November were not replies, while 52% are in response to verified accounts (ie public figures or brands), with only 16.9% between non-verified accounts.

References

- Abramson, K. (2014). Turning up the lights on gaslighting. Philosophical Perspectives, 28(1), 1–30. doi:10.1111/phpe.12046

- Bailey, A. (2020). Gaslighting and epistemic harm: Editor’s introduction. Hypatia, 35(4), 667–673. doi:10.1017/hyp.2020.42

- Barton, R., & Whitehead, J. A. (1969). The gas-light phenomenon. The Lancet, 293(7608), 1258–1260. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(69)92133-3

- Brockes, E. (2018). From gaslighting to gammon, 2018ʹs buzzwords reflect our toxic times. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/nov/18/gaslighting-gammon-year-buzzwords-oxford-dictionaries

- Bruns, A. (2019). Are Filter Bubbles Real?. United Kingdom: Polity Press.

- d'Ancona, M. (2017). Post-Truth: The New War on Truth and How to Fight Back. United Kingdom: Ebury Publishing.

- Davis, A. M., & Ernst, R. (2019). Racial gaslighting. Politics, Groups, and Identities, 7(4), 761–774. doi:10.1080/21565503.2017.1403934

- Duca, L. (2016). Donald trump is gaslighting America. Teen Vogue. Retrieved from https://www.teenvogue.com/story/donald-trump-is-gaslighting-america

- Elizabeth Dubois & Grant Blank (2018) The echo chamber is overstated: the moderating effect of political interest and diverse media, Information, Communication & Society, 21:5, 729–745, DOI: 10.1080/1369118X.2018.1428656

- Ghitis, F. (2017). Donald Trump is ‘gaslighting’ all of us. CNN. Retrieved from https://edition.cnn.com/2017/01/10/opinions/donald-trump-is-gaslighting-america-ghitis/

- Haraway, D. (1988). Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Feminist Studies, 14(3), 575–599. doi:10.2307/3178066

- Hartsock, N. (1998). The feminist standpoint revisited and other essays. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1981). Metaphors we live by. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Lewandowsky, S., & Cook, J. (2020). The conspiracy theory handbook. Climate Change Communication.

- McKinnon, R. (2017). Allies behaving badly: Gaslighting as epistemic injustice. In G. Pohlhaus Jr., I. J. Kidd, & J. Medina (Eds.), Routledge handbook on epistemic injustice. New York, NY: Routledge, 167–174.

- Pariser, E. (2011). The Filter Bubble: What The Internet Is Hiding From You. United Kingdom: Penguin Books Limited.

- Peeters, S., & Hagen, S. In press. The 4CAT Capture and Analysis Toolkit: A Modular Tool for Transparent and Traceable Social Media Research. Computational Communication Research, Forthcoming. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3914892.

- Peeters, S., Tuters, M. W., & Zeeuw, T. (2021). On the vernacular language games of an antagonistic online subculture. Frontiers in Big Data, 4(65). doi:10.3389/fdata.2021.718368

- Pohlhaus, G. (2020). Gaslighting and echoing, or why collective epistemic resistance is not a “witch hunt.” Hypatia, 35(4), 674–686. doi:10.1017/hyp.2020.29

- Pomerantsev, P. (2019). This Is Not Propaganda: Adventures in the War Against Reality. United Kingdom: Faber & Faber.

- Rietdijk, N. (2021). Post-truth politics and collective gaslighting. Episteme, 1–17. doi:10.1017/epi.2021.24

- Rogers, R. (2012). Mapping and the politics of web space. Theory, Culture & Society, 29(4–5), 193–219. doi:10.1177/0263276412450926

- Rogers, R. (2017). Foundations of digital methods: Query design. In M. T. Schäfer & K. van Es (Eds.), The datafied society: Studying culture through data (pp. 75–94). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Ruíz, E. (2020). Cultural Gaslighting. Hypatia, 35(4), 687–713. doi:10.1017/hyp.2020.33

- Simon, F. M., & Camargo, C. Q. (2021). Autopsy of a metaphor: The origins, use and blind spots of the ‘infodemic.’ New Media & Society, 1–22.

- Sweet, P. L. (2019). The sociology of gaslighting. American Sociological Review, 84(5), 851–875. doi:10.1177/0003122419874843

- Theocharis, Y., Cardenal, A., Jin, S., Aalberg, T., Hopmann, D. N., Strömbäck, J., Castro, L., Esser, F., Van Aelst, P., de Vreese, C., Corbu, N., Koc-Michalska, K., Matthes, J., Schemer, C., Sheafer, T., Splendore, S., Stanyer, J., Stępińska, A., & Štětka, V. (2021). Does the platform matter? Social media and COVID-19 conspiracy theory beliefs in 17 countries. New Media & Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211045666

- Tuters, M., & Hagen, S. (2020). (((They))) rule: Memetic antagonism and nebulous othering on 4chan. New media & society, 22(12), 2218–2237.

- Wattenberg, M., & Viégas, F. B. (2008). The word tree, an interactive visual concordance. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, 14(6), 1221–1228. doi:10.1109/TVCG.2008.172

- Zelenkauskaite, A., Toivanen, P., Huhtamaki, J., & Valaskivi, K. (2020). Shades of hatred online: 4chan memetic duplicate circulation surge during hybrid media events. First Monday. Retrieved from https://firstmonday.org/article/view/11075/10029