ABSTRACT

What is the role of different epistemic modes in how authority is established in right-leaning conspiratorial narratives? This paper sets out to answer this question through a mixed methods analysis. The first section sets out a model for the analysis of epistemic contestations, using six epistemic modes. This is then applied to a data set of Telegram posts in which key terms are used to identify these epistemic modes. Two questions were then asked of the data. First, how is power related to different kinds of knowledge claims in the far-right conspiratorial milieu? Second, what is the role of these different epistemic modes in how authority is established in right-leaning conspiratorial narratives? How does the epistemology of QAnon influence how they argue? We found that while a broader set of epistemic modes could be identified, there were contestations internally also, particularly around moments of “failed prophecy,” and the role of Christianity and esoteric spiritualities.

Introduction

One of the stranger and persistent aspects of the contemporary political climate, particularly in the United States, is the fusion of conspiratorial movements, far-right groups, and mainstream politics (Amarasingam, Citation2019). Perhaps no other movement is indicative of this worrying trend than the QAnon conspiracy, which started as a fairly insignificant online phenomenon in the dark corners of cyberspace, but which has now blossomed into a mass movement causing social polarization and even tipping over into violence on several occasions (Amarasingam & Argentino, Citation2020a). The QAnon conspiracy began on 28 October 2017, with a post on 4Chan’s /pol/ (politically incorrect) page declaring that Hillary Clinton would be arrested in the next few days. What is interesting here, of course, is that the fact that Clinton – or anyone for that matter – was not arrested, as the anonymous poster had predicted, means that the entire movement began in a moment of failed prophecy (Amarasingam and Argentino Citation2020b; Festinger, Riecken, & Schachter, Citation1964/1965).

As it stands today, QAnon continues to be a “decentralized ideology rooted in an unfounded conspiracy theory that a globally active ‘Deep State’ cabal of satanic pedophile elites is responsible for all the evil in the world” (Argentino & Amarasingam, Citation2021, p. 19). Adherents of QAnon believe that former US President Donald Trump had learned of this deep state cabal and was attempting to dismantle it from within, and was depending on his supporters to help him in this campaign. Eventually, these evil doers and those that enable them would be arrested in a major event known as “the Storm.” Following these mass arrests, the rest of humanity would be awakened to the true evil that was operating right under their noses. This moment of realization – known as “the Great Awakening” in QAnon terminology – would lead to a new society free of evil. As Mike Rothschild (Citation2021, p. 5) notes, “it’s not just a conspiracy theory or game to these people. It’s a ringside ticket to the final match between good and evil.”

With conspiracy theories becoming more visible and more mainstreamed, there has been efforts to understand how they can be countered. It is this broad concern to which this paper tries to speak, using a unique theoretical approach to analyze a dataset of QAnon posts on Telegram. This paper sets out to answer two questions. First, how is the episteme of the QAnon social media milieu constituted? Which is to say, how is power related to different kinds of knowledge claims in the far-right conspiratorial milieu? And second, what is the role of these different epistemic modes in how authority is established in right-leaning conspiratorial narratives? In short, this paper sets out to ask how conspiracy theorists argue and looks to get a better understanding of the kinds of evidence they use to make truth claims (Butter, Citation2020).

To do this, the paper uses a mixed methods analysis. The first section sets out a model for the analysis of epistemic contestations, through competition over epistemic capital. This model, developed by Robertson (Citation2016, Citation2021a) from Bourdieu’s model of fields and capital, starts from the premise that all socialized fields of knowledge – epistemes – are constituted with multiple types of knowledge claims, or epistemic modes, of which we have identified six, detailed below. Any given episteme will grant authority to some of the modes (some of which will be authoritative than others) and reject others as lacking any access to truth; but in all cases the agent who most skillfully wields the modes of the episteme in which they operate will gain the most capital, and thereby more power.

While this is elaborated below in the methodology section, this model was then applied to a data set of Telegram posts in which key terms are used to identify these epistemic modes. Two questions were then asked of the data. First, how do QAnon supporters argue? What sorts of epistemic modes do they draw upon to make their arguments and communicate with fellow supporters? Second, what is the role of these different epistemic modes in how authority is established in right-leaning conspiratorial narratives? Much of the literature on conspiracy theories, social media, and popular communication tends to focus on major themes in conspiracy content or the diffusion of content across social media platforms – in other words, the content. We argue here that a relatively understudied aspect of conspiracy theories and popular communication is how that content is legitimized – in other words, how they argue. As Valaskivi and Robertson note in their introduction to this issue, epistemic contestations take place on two levels; on the societal level, which groups are allowed to speak authoritatively, which we can think of as intergroup epistemic contestations; as well as contestations over what kinds of knowledge are prioritized and legitimized within groups, which we can call intragroup epistemic contestations.

This paper remains epistemically agnostic; we make no judgments about the value or reliability of the various epistemic modes,Footnote1 nor declare them of equal validity. Our purpose lies in analyzing how the modes are utilized by different social groups.

What are epistemic modes?

Michel Foucault’s work established the existence of socio-historically contingent epistemes (Foucault, Citation1966/1970/1970, p. xxii) – systems in which power and knowledge are combined. An episteme may be thought of as a specific instance of hegemony, in the Gramscian sense of ideological, moral and cultural dominance by consent (Citation1999, p. 194).Footnote2 Different epistemes are predicated upon different strategies for establishing “truth”; for example, the episteme in which the Catholic Church was the arbiter of Truth was superseded by the Enlightenment episteme in which science became paramount. These different types of knowledge claims are mobilized by actors in competition for the epistemic capital of the field of knowledge in different ways. Pierre Bourdieu identified two principal currencies for the distribution of power, providing advantages in influencing other actors to work toward particular ends: economic capital – wealth, what you own – and symbolic capital (aka cultural capital) – what you know, including skills and use of language. Epistemic capital, on the other hand, does not map what you know, but how you know – “the way in which actors within the intellectual field engage in strategies aimed at maximising not merely resources and status but also … better knowledge of the world” (Maton, Citation2003, p. 62). So, when an actor cites academic papers, or invokes their “lived experience,” or claims that God spoke to them, they are mobilizing particular forms of epistemic capital in order to influence others, and thereby gain advantage within the field.Footnote3 Different epistemic modes are likely to be more persuasive in different contexts – citing an academic paper at an academic conference to make one’s argument as opposed to citing a dream, for instance. Citing an FBI press release as evidence of a growing threat may be convincing to many, but in conspiratorial circles it might be seen as providing support for corrupt and sinister law enforcement agencies. In this way, this paper examines how QAnon supporters argue, and looks at the kinds of argumentative/epistemic modes they call upon to persuade and make their case to fellow believers.

The dominant forms of epistemic capital in the contemporary world are Science, Tradition (in both Institutional and Social Group forms),Experience, Channeling and Assemblagé.Footnote4 These terms organize emic knowledge claims according to two criteria: firstly, whether the claim is understood to be legitimized individually (such as eyewitness testimony) or collectively (such as a religious denomination); and secondly, whether the knowledge claim is understood to have an internal source (as in personal experience) or an external source (such as the US Constitution). We understand, of course, that the contents and interpretation of all these knowledge claims are shaped by broader discourses; nevertheless, our concern here is how those making the claims understand them.

Science became, from the eighteenth century, the most prominent form of epistemic capital in Europe and its colonies (though in practice, tradition and channeled knowledge remained just as powerful). Scientific knowledge is collective and relies upon the criterion of reproducibility, although as Kuhn (Citation1964), Latour and Woolgar (Citation1979), Latour (Citation1993) and others have shown, the boundaries of scientific knowledge are less clear-cut than is generally acknowledged. Tradition is essentially “people like us do things like this,” and like science, it is collective. It can be found in both top-down Institutional forms (such as legal systems, governmental systems, churches, etc.) and bottom-up Social Group forms (social norms, taboos, customs and “common sense”). Experience, an increasingly prominent form of epistemic capital since the latter half of the twentieth century (Hammer, Citation2001, p. 339), is individual. Its criterion is an emotional response of “truthiness” – one feels that it is true, and indeed it is often emotionally driven. Channeled knowledge is also individual, but is taken by the claimant and/or their audience as coming from an external source, such as a Higher Power or Intelligence, a specific supernatural agency such as a god, angel or demon, or from extra-terrestrials. Its truth criterion rests in its claimed “miraculous” nature, most commonly that it foretells the future (a la Weber, Citation1964, p. 328). Finally, Assemblagé links numerous smaller pieces of data across time, space and context “dot-connecting” to create highly suggestive narratives, while blurring the specific details and the mystification of the selection process.

Epistemes are not usually defined by recourse to a single, specific form of epistemic capital, but rather create distinct formations in which strategies are legitimized or stigmatized in different degrees. Science and Institutional Tradition dominate our present episteme, and are presented as exclusively authoritative. Nevertheless, other modes do appear – some Channeled claims are domesticated via religious institutions and legal protections for “faith” communities, for example. Claims of special knowledge through Channeling and Experience are by no means restricted to religions, however, and as we will show, they make up a small, yet significant proportion of the QAnon episteme. The next section explains how we set out to map that episteme, by identifying the different epistemic modes being mobilized, and their relative capital within it.

Method and sample

Social media platforms are the primary means by which conspiratorial ideas now develop and maintain a community of likeminded followers. The ecosystem of social media sites is increasingly diverse, especially as more mainstream companies like Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram have come to take more proactive measures to limit extremism, hate speech, and misinformation on their platforms. For our analysis, we focused on a corpus of data gathered from around 700 Telegram channels and groups created and administered by QAnon influencers and supporters. Telegram has grown in recent years to become the platform of choice for a variety of social movements and extremist groups. In November 2015, with ISIS supporters getting roundly suspended from mainstream social media platforms, they migrated en masse to Telegram, where they enjoyed relative freedom to post content, and continue recruitment efforts (Amarasingam, Maher, & Winter, Citation2021). After social media companies started more proactively targeting them for removal in 2017 and 2018, Telegram has since become ground zero for far-right propaganda and recruitment as well.

The popularity of Telegram is largely linked not only to its general libertarian approach to unseemly content, but also its channel function. A Telegram channel allows the host to “broadcast” messages to subscribers in a unidirectional manner. Users can subscribe to different channels, but cannot contribute to the ongoing discussion. Telegram groups, which do allow for back-and-forth debate and conversation are also popular, but generally less prevalent than channels. Groups are moderated by administrators and are typically limited to 200 members. When a group has 200 members, administrators have the option to upgrade the group to a supergroup, the limit to which has evolved from 5,000 members to the current limit of 100,000.

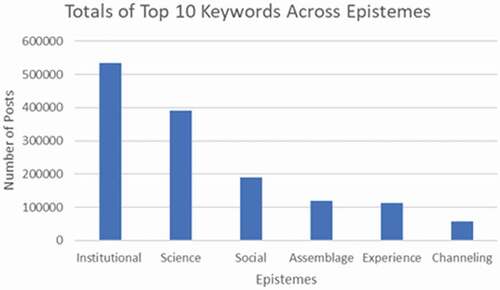

For this paper, we began by creating a list of keywords that were indicative of the different epistemic modes mentioned above.Footnote5 These keywords were then searched for in around 700 Telegram channels and groups created by QAnon influencers and supporters, containing a total of approximately 42 million posts between the dates of March 2016 and July 2021. The top 10 keywords that returned the highest number of posts, totaled 1.4 million posts across the six epistemic modes (see ). While this may seem like a small number compared to the total number of posts, it is important to keep in mind that many Telegram groups are made up of free-flowing conversation about a variety of topics, from their daily activities to more important questions related to politics.

Figure 1. Totals of the top 10 keywords found in the totality of QAnon related Telegram channels across the six epistemic modes.

Each post in our dataset was collected from channels, groups and supergroups run by QAnon influencers and supporters. We automated this process using a custom-built piece of software developed in 2017, which works within Telegram’s limited application programming interfaces (APIs). The Telegram crawler automatically archived all posts from all the channels, groups and supergroups to which it was given access. While this sample does not constitute the full universe of QAnon channels and groups on Telegram, it is expansive enough to be considered largely, and essentially, representative of them. Because the channels and groups the crawler archives must be selected by the researchers themselves, there is a high degree of confidence that the level of “noise” in the data is minimal. In other words, we selected channels and groups after being certain that they were associated with the QAnon movement.

Each data point listed by the crawler includes the date of the post, the name of the group/channel/supergroup, and the type of post it is (video, photo, text, etc.). In addition to this, the crawler cataloged all text associated with a particular post, but not photographs and videos. In other words, if there is a post with a photograph and text appended to it, the scraper will download the entirety of the text, but only indicate that there is an associated photograph. For the purposes of this paper, which is focused on textual forms of argumentation, this limitation proved insignificant. However, because the text of each data point was recorded, we were able to examine the data qualitatively, allowing us to explore how different epistemic modes are mobilized in specific contexts.

Analysis

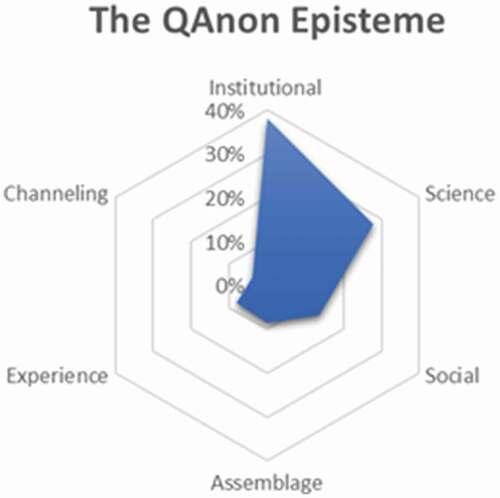

Our analysis was able to map out the QAnon episteme, identifying the relative frequency of appeals to the different epistemic modes (see ). The Institutional mode was found to be most prevalent (38%), followed by Science (28%), Social (13%), Assemblagé (8%), Experience (8%), and Channeling (4%). In the absence of similar analyses of the broader social media sphere (such as analyses of the modes on say all of Twitter and Facebook) we are unable to offer a direct comparison with the general population, but we can make a few observations nevertheless. The first is that the relative distribution of the modes is close to what we would expect to find in the general population, with Institutional and Scientific modes dominating. This is significant, as it contraindicates the common assertion that these communities are anti-scientific. Rather, what we find is that Science holds a great deal of epistemic capital in such communities, but scientific “facts” are generally gleaned from online echo chambers away from trusted institutions of science that the general public may depend on. It’s also clear that they see these epistemic modes as most prevalent in society, and ones they need to most vociferously argue against and dismantle.

Similarly, we might be surprised at the prominence of the Institutional mode, given the high degree of correlation between conspiracy theories and distrust. We might ask, then, what institutions would such people put their faith in? One answer is the US itself, as embodied in the Constitution, which seems largely unchallenged as a source of moral truth and social good, and is in effect as much an unchallengeable “sacred” document as the Christian Bible, if not more so. The 2nd Amendment, for instance, means that bearing arms is presented not as a legal right, but an “inalienable” right, almost existential in its import.

Note, however, that appeals to Social Group Tradition are far less prominent than Institutional Tradition. On the face of it, this seems to contradict the populist right’s self-presentation as representing “We the People” against powerful elites. However, taking these two factors together – trust in institutions and laws but a distrust of the majority of ones’ social peers – fits an understanding of the political right as at core a worldview in which the individual is of less important than the institutional order of the State – be that Queen, country or God. It also meshes with the trajectory of populist right-wing governments who use social issues (“culture wars”) to gain support, while enacting policies which reduce checks and balances on institutional power (and often, that held by the leader themselves). This might suggest a reason why the Experience mode is smaller than we might expect; the individual’s inner authority is of less importance than the Institutional authority of the State and Law. It is this faith in tradition that leads to the conservatism that typifies the right. It also suggests that the internal social cohesion of the conspiratorial right – and QAnon in particular – is weak. We return to that in the section on intragroup contestations below.

Although Channeling is the least prominent mode, the result is still significant: 4% means that one in every twenty-five knowledge claims in the QAnon media sphere refers to communication with a non-human intelligence. So, to summarize: in the QAnon episteme, knowledge claims appealing to Institutional Tradition are paramount, while Social Group Tradition is weak, and Science is relativized by Experience, Assemblage and Channeled knowledge (see ).

Figure 2. The episteme of QAnon, according to the relative frequency of appeals to different epistemic modes.

These figures should be taken only illustratively; neither the data we have nor the scope of this paper allows us a full quantitative analysis. Nevertheless, this mixture of epistemic modes is vital to understand, as it is in the strategic mobilization of these modes, even if sometimes contradictory, that the discursive power of this worldview lies. Those who can most successfully mobilize all of these strategies can speak to the broadest audience and so gain the most power.Footnote6

Perhaps the most valuable result, however, was in how disentangling the different modes allowed us to see in more detail how members of the community made arguments. By separating out appeals to specific epistemic modes, their strategic mobilization to gain epistemic capital became clear – as well as where these appeals were contested. We were therefore able to use the data more granularly to identify and interrogate both intergroup and intragroup epistemic contestations. The following sections discuss two illustrative examples from the data: first, how QAnon supporters appeal to multiple epistemic modes to challenge the apparent failure of Q’s prophecies, an intergroup contestation between “the people” and “the elites”; and second, how QAnon deals with competing claims of experience (specifically, “gnosis”) within the movement.

Intergroup contestations: failed prophecy

Given that the movement began with a moment of failed prophecy, as we noted, it is perhaps unsurprising that we find multiple examples in the sample. Anons offer multiple different explanations, mobilizing the full range of epistemic modes, for why their understanding of the situation was not accepted by those working within the hegemonic episteme (i.e., everyone else). This section examines these dynamics as an example of an intergroup epistemic contestation, between “the people” and “the elites.”

Whether or not we consider QAnon to be a religious movement, it certainly has a millennial aspect. As noted above, the movement began with a failed prophecy, Q’s drops were widely interpreted as prophetic by the wider Anon community, and “Trust the Plan” became one of the movement’s rallying cries. Multiple dates were suggested for the commencement of “The Storm” (the most common name for the endpoint of Trump’s supposed Plan), with January 6th eventually being established as the key date. The Storm is usually predicted to involve a wave of arrests of (mostly) Democratic politicians, media figures and others accused of corruption, collusion and, frequently, Satanic child abuse. The Storm is seen as a vanguard of a longer period of global societal transformation:

These times we are in are a great test to see who is faithful and who was pretending. This is the great Awakening before the times of destruction come.

The ambiguity of the term is a feature, not a bug – it allows it to be presented as a political narrative, rather than a religious one, while remaining equally unoffensive to Christian, pagan, New Age and religiously unaffiliated Anons. It also helps to obscure that some Christian Anons see The Storm as the Biblical Tribulation, but others see it as a transformation in consciousness in terms clearly drawing from New Age thought:

[The Great Awakening] is due to the constant waves of super-charged plasma rays emanating to us from the very core of our milky way galaxy! These rays have now entered the crystalline earth, discharging an ionizing type of radiation that neutralizes, cleans, recodes, energizes, transforms and rebuilds our DNA, allowing all living systems to expand and breathe more light!

Nevertheless, these teleological narratives all draw heavily from the well of Protestant premillennialism. They belong in a lineage beginning with heterodox Protestant groups in the 19th century, and run through Theosophy, the New Age, the millennium and 2012 (see Robertson, Citation2016, pp. 39–43). We can identify several common features shared by these and QAnon: a sharp distinction between the ingroup and an elite outgroup; a hermeneutic tradition of seeking signs of the End Times in current events and popular culture; and a teleological dialectic in which the present is simultaneously humanity’s darkest moment and the point at which the global awakening begins. Importantly for this paper, we can also identify commonalities which suggest a similar episteme, with appeals to the full range of epistemic strategies. In all of these cases, direct spiritual experience and channeled communications (whether with extraterrestrial intelligences or charismatic “gifts of the spirit”) have a high value – and are therefore a common point of contestation.

January 6th came and went, not without incident, but without a wave of arrests of left-wing figures and without Trump being returned to office. As such, it makes sense to look at the responses to this in our data set through the classic sociological model of failed prophecy (a la Festinger et al., Citation1964/Citation1965). Festinger suggested that the believers experienced cognitive dissonance when the prophecy which they believed did not match the reality they experienced, and identified a number of strategies which believers might utilize to reconcile these (see also Amarasingam and Argentino Citation2020b). These include miscalculation (reception was garbled), spiritualization (it happened, but only on the spiritual plane), aversion (the predicted outcome was prevented by the prophecy and the actions of the believers), and privation (it happened but was only ever for the insiders). We see all of these strategies represented in our data, as well as prevention – that the events revealed an unsuspected counter-agency, whose actions have prevented the (originally correct) prophecy from being fulfilled (Robertson, Citation2016, pp. 7–8). Given that this strategy is essentially conspiratorial thinking, it is unsurprising that we find numerous examples in the data, many of which (as in the following example) also reposition it as merely the beginning of the Great Awakening:

I’m hearing from several people Q will not speak again, Q is done, the job is complete. If you hear that anything new just came from Qanon. It is a lie! Q’s only focus was to wake up thousands of us, or even millions, to the great awakening! That was achieved, now we that followed Q, Qclearance, Qanon from Oct 2017 are to comfort and calm the rest of the population after these military ops, which are occurring now, are completed.

Central to Festinger’s argument is that cognitive dissonance is an unstable and unsustainable condition, and the strategies he presents are rationalizations – in other words, explanations in which both the prophecy and the situation of apparent failure can be correct. Clearly, appealing to a wider range of epistemic modes would be helpful in this; if you cannot support your position using Science or Tradition, then perhaps you can using Experience, Channeling or Assemblagé.. Indeed, our data showed multiple examples of Anons drawing upon this full range of epistemic modes to support their recontextualization of the prophecy.

Our quantitative analysis established the importance of the Institutional Tradition mode for QAnon, and indeed, much of the “Stop the Steal” discourse revolved around various legal strategies by which the election result might be challenged, and Trump returned to power. The legal system, like the US Constitution, can be seen as an embodiment of Institutional Tradition, and multiple posts attempt to use these to make the case for a miscalculation of the date, and so argue that the prophecy was therefore still correct. For example, some argued that the “real” inauguration date was March 4th, because Franklin Roosevelt had not legitimately changed it legally to January 6th in 1933. Therefore, it was still possible for Trump to be legitimately inaugurated for a second term.

Another version of miscalculation drawing on Institutional Tradition was the claim that the prophecy was not that Trump would serve a second term, and widely interpreted, but rather that wouldn’t be succeeded. This was because he was the last President:

What sort of things have presidents? Corporations have presidents. Since dismantling the banking act of 1871, America will now go back to being a Constitutional Republic … once you understand the bigger picture and what Trump is working tirelessly to restore, and why they have made him out to be the bad guy this whole time, you’ll realize why it had to be this way.

Clearly, these arguments are not very convincing to outsiders. Yet, the more prima face dubious the claim, the greater the need for support from counter-hegemonic epistemic modes. Frequently, appeals are made to Experience, and the Anons feelings that the Storm is coming, that they should “have faith” and “Trust the Plan” – even if that means rejecting the experiential evidence of ones’ own senses and refusing to “believe your eyes or your ears.”

A small but vocal and highly creative subset make frequent appeals to the Channeling mode. Sometimes these are with religious figures (usually Christian, though New Age and Theosophical figures also appear), but typically, they appeal to extraterrestrial intelligences. This places QAnon and The Storm into a hybrid tradition of UFO conspiracism that emerged in the US Christian right in the 1980s, most famously in William Milton Cooper’s Behold, A Pale Horse (Citation1991), which portrayed the US government as covering up that they were working with different extraterrestrial races, all of whom were members of a “Galactic Federation” (Barkun, Citation2003; Robertson, Citation2016). In an example of the aversion strategy, one poster uses channeled information to argue that The Storm was actually the Galactic Federation’s plan, and the next stage would commence only when they were ready:

The irony of it, is that “The Plan” is a series of triggers encoded into a quantum AI computer. What unlocks each unfolding step of the way are the aggregated readiness levels of humanity … All human life on this planet has an invisible thread going from the top of their heads to a quantum AI supercomputer housed on board friendly alien craft above their town or city. All threads convey real time information to the AI, aggregating the mood of humanity so the white hats [benevolent ETs] and Galactic Federation allies know what we’re ready for … “The Plan” we’re all being asked to trust has embedded thresholds programmed into it.

Later in this discussion, a poster appeals to Experience (their own, and other peoples’), Channeling and Tradition (it’s in the Bible!) in a single post:

I’ve been on a Pleiadean ship twice [Experience], and I’ve also fought Reptilians on a spiritual level [Channelling]. There are actually many races from other planets that people have had direct contact with, and I’ve met some of those folks myself [Experience]. Can any of us prove it? Probably not. Did it really happen? Absolutely … go within and connect with and through your own heart [Experience]. The White Hats are highly conscious beings and they won’t reveal themselves to just anyone, but their presence can be known and felt if we are tuned in to their vibrational frequency [Experience] via love and goodness. And btw, ETs are mentioned in the Bible [Tradition].

It is this accumulation of epistemic capital – both hegemonic and counter-hegemonic – that gives these arguments their rhetorical power within the QAnon episteme. So, analyses which present such arguments as simply “counter-factual” fail to grasp that the issue is how one determines what counts as a fact. Evidence is presented, but often it appeals to epistemic truth-conditions that are contrary to the dominant episteme. In other words, the issue is epistemic, not merely evidential.

But it is also important to remember that groups like QAnon are not monolithic – they are a common flag which bring together otherwise disparate groups over particular issues, for a relatively short time. Paying attention to intragroup epistemic contestations can help us to disaggregate these internal differences and reveal epistemic fault lines, as our next section will show.

Intragroup contestations: gnosis

QAnon is not a neatly boundaried movement in a strict sense. There are a core group of supporters (“Anons”) who followed the Q “drops,” but as QAnon became a popular “brand,” it began to be used to describe much more widely. In Europe, where Trumpism was less of a factor, QAnon was more associated with the idea of “elite paedophiles,” essentially becoming a new name for an already long-running conspiratorial Satanic Ritual Abuse narrative that goes back to at least the 1960s (Lawrence & Davis, Citation2020, p. 4; Sardarizadeh, Citation2020). The “Save the Children” march in London in late 2020 was an example of this, generally covered in the UK press as a QAnon event, but organized and led by figures who had been involved in the Satanic Ritual Abuse movement since the 1990s (Bartholomew, Citation2020). Indeed, it is this tendency to include all of these disparate groups as now part of the QAnon umbrella which has led to some of the larger estimates of its size. However, the intragroup epistemic contestations identified by our analysis may indicate where the lines of fracture will eventually begin to appear.

One of our keywords indicating claims of Experience was “Gnosis,” which we selected due to its frequency in the alternative milieu at large to describe special knowledge gained through direct experience (Robertson, Citation2014). The surprisingly large number of occurrences in the data set motivated us to explore the data in greater detail, to understand what the particular appeal of this term was for those utilizing the Experience mode.

Emerging in second century polemics, Gnosis (and/or Gnosticism) has been used historically to describe both pre-Roman “original” Christianity, and its opposite, a magical, ritualized corruption of “true” Christianity (Robertson, Citation2021b). This, coupled with the fact that it doesn’t actually refer to identifiable historical communities and therefore has absolutely no restraints on its application, means that it is equally useful for both the Christian and esoteric/Pagan sections of the far-right, while obscuring the epistemological gulf between them. Indeed, terminology drawn from Gnosticism have been increasingly visible in the conspiratorial milieu since those two tendencies began to increasingly work together during the 1990s.

Throughout the data set, Gnosis is used to indicate experienced knowledge, as distinct from simply “believed” knowledge – in both a religious sense, as well as the more secular sense of “having done one’s own research.” Many Anons present Christianity as the only path to true knowledge, and Gnosis is frequently used to indicate the direct Experience of this truth. This is particularly the case when contrasting the personal Experience with the established churches:

Bottom line of Gnostic gospels is that God is within … Through knowledge, or gnosis, aka true understanding of the nature of reality, no dogma, doctrine, rite or sacrifice is needed. No religious hierarchy is needed either. What did Jesus say? “The Kingdom of God is within”. Who went after Jesus? Established religious caste. Who compiled, cherry-picked and edited the regular gospels? Constantine in the 4th century AD as the new dogma for the Roman Empire. Organised Christianity became a tool of political control. Christ as example is entirely gnostic in nature.

This is, of course, an epistemic contestation itself, between the Experiential and Institutional Tradition modes. However, rather than the churches being merely corrupted, more conspiratorial versions have the churches as created by Satanic Elites. In some cases, the churches are there to deliberately obscure the “true” (i.e. Gnostic) Christian teachings from the masses – “to deprive you of the acknowledgment (gnosis) which gives you the victory to overcome Satan and his demons.” For others, however, “Gnosis is Luciferianism,” and institutionalized Christianity is constructed entirely to obscure this fact. Interestingly, these narratives appeal both to anti-elite Christians and to pagans who want to present their beliefs as older than Christianity (and therefore possessing more Institutional Tradition capital).

The reader may not be surprised to find that this often incorporates antisemitism. One poster, citing “Personal Unverified Gnosis” as their source, describes “Jesus Christ’s demon father” as eating an Aryan child after a long day of “orchestrating rape, death, and worse.” Another talks of “Hitlerism” as “the age-old religion of Aryan Kristianity,” “the Revelation of the God-men” and “the power and glory of the Aryan God.” Nor are these isolated posts; one meme which was reposted in multiple groups and supergroups suggests that gnosis is in fact the moment of acceding to the truth of such racialism:

Saint Anders Breivik was, for me, that flash of gnosis that woke my Being from its long dead slumber. Then more solitary Warriors rose up. here. there. Now, many lone wolves have formed packs, tribes. The coming Aryan Apocalypse will be a revelation of infectious violence. Torches soaked in accelerant. Stalking packs of matches.

Only one post that we found seemed to question the epistemic validity of appeals to gnostic Experience, however, underlining that these counter-hegemonic modes are central to the episteme of groups like QAnon:

And … even if one did in fact KNOW, sometimes referred to as “gnosis”, even if God or Buddha or Allah or Jesus appears right in your room so that you might touch them and see them and verify their reality, this is something you could not prove either. Thus even someone who knows simply sounds like a mental case, and is not to be believed by whomever might hear him speak of it. Tough gig.

Yet this post neatly illustrates our central point. Each of these epistemic modes, each different kind of knowledge claim, makes sense if – and only if – you accept its potential veracity. Experience has its own truth criteria. You might sound like a “mental case” when appealing to Gnosis to someone in the hegemonic episteme, but to challenge the claim from within that position will have no effect on those who also accept Experience, Channeling and Assemblage. This is why “Post Truth” is a misunderstanding. There is not less truth, but more – just not all of the same type.

Conclusion

In this paper, we have presented a new method for analyzing media discourse (in this case, Telegram posts) by isolating different epistemic modes, and using this to tease out points of confluence and contestation. We suggest that the approach we have suggested here, focusing on epistemic modes and contestations, could be particularly useful for researching groups and movements, like QAnon, with one foot in the sphere of religion and one foot in political ideology. While limitations of space and dataset mean that this is only a preliminary study, we hope that it has demonstrated the utility of the approach, while exhibiting the need for more detailed follow-up studies. Possible follow-up studies could include epistemic comparisons of different right-wing groups (do Christian groups have the same episteme as neo-pagan groups?), different religious groups (do Catholic groups put a greater stress on Tradition, and Protestant groups on Experience?), and of different countries and of different social media platforms. We suggest avoiding categorizing such groups as distinctly “religious,” “secular,” “political,” “extremist” and so on – categorizations which ultimately have little substantive core. Instead, a focus on their epistemic structure will reveal more substantive points of commonality and contestation upon which to base our analyses.

It is clear that there is a keen need to better understand the multiple epistemological underpinnings of today’s polarized political discourse and social media sphere. The epistemic capital approach we have presented here, with its focus on how knowledge is claimed and justified, is vital for understanding – and countering – the so-called “Post-Truth Age” today, and how it will evolve in the future.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

David G. Robertson

David G. Robertson is Lecturer in Religious Studies at the Open University, co-founder of the Religious Studies Project, and co-editor of the journal Implicit Religion. His work focuses on claims of special knowledge in religions, conspiracy theories and beyond. He is the author of Gnosticism and the History of Religions (2021) and UFOs, the New Age and Conspiracy Theories: Millennial Conspiracism (2016), and co-editor of After World Religions: Reconstructing Religious Studies (Equinox 2016) and the Handbook of Conspiracy Theories and Contemporary Religion (Brill 2018). Twitter: @d_g_robertson

Amarnath Amarasingam

Amarnath Amarasingam is an Assistant Professor in the School of Religion, and is cross-appointed to the Department of Political Studies, at Queen’s University in Ontario, Canada. He is also a Senior Fellow with the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation. His research interests are in terrorism, radicalization and extremism, online communities, diaspora politics, post-war reconstruction, and the sociology of religion. He is the author of Pain, Pride, and Politics: Sri Lankan Tamil Activism in Canada (2015), and the co-editor of Sri Lanka: The Struggle for Peace in the Aftermath of War (2016). He has also published over 40 peer-reviewed articles and book chapters, has presented papers at over 100 national and international conferences, and has written for The New York Times, The Monkey Case, The Washington Post, CNN, Politico, The Atlantic, and Foreign Affairs. He has been interviewed on CNN, PBS Newshour, CBC, BBC, and a variety of other media outlets. He tweets at @AmarAmarasingam

Notes

1. Indeed, it is impossible to do so without adopting a particular episteme. One cannot assess the truth-value of a particular claim without adopting the truth criterion of one or other mode. To declare channeled information “false” because it does not confirm to the truth criterion of Science is to make a category error. Nevertheless, this is not postmodern relativism on our part – rather, we are “bracketing” our epistemic position to achieve a more disinterested analysis of a different episteme.

2. One might argue that hegemony is the process though which an episteme is promulgated. The media, education and legal system communicates not only the moral values and ideological narratives of the ruling elite, but also also which epistemic modes are permissible, though who they cite as authoritative (scientists, priests, etc).

3. This model is explored in greater depth in (Robertson, Citation2021a, Citation2018, Citation2016).

4. We capitalize these throughout to make it clear when we are referring to an epistemic mode, rather than the everyday use of the word.

5. As illustrative examples, the Science mode was indicated by “rational”, “academic”, “falsify”, “professor” and “data”, etc.; Institutional Tradition by “law”, “history”, “rights”, “bible”, “constitution”, etc.; and Experience was indicated by “witness”, “insider”, “testimony”, “rumour” and “gnosis”, etc.

6. See Robertson (Citation2018) for specific case studies of David Icke and Alex Jones.

References

- Amarasingam, A. (2019). The impact of conspiracy theories and how to counter them: Reviewing the literature on conspiracy theories and radicalization to violence. In A. Richards, D. Margolin, & N. Scremin (Eds.), Jihadist terror: New threats, new responses. London, UK: Bloomsbury. pp. 27–39.

- Amarasingam, A., & Argentino, M.-A. (2020a). The QAnon conspiracy theory: A security threat in the making? CTC Sentinel, 13(7), 37–44.

- Amarasingam, A., & Argentino, M.-A. (2020b, October 28). QAnon’s predictions haven’t come true; so how does the movement survive the failure of prophecy? Religion Dispatches. Retrieved from https://religiondispatches.org/qanons-predictions-havent-come-true-so-how-does-the-movement-survive-the-failure-of-prophecy/

- Amarasingam, A., Maher, S., & Winter, C. (2021, January 8). How Telegram disruption impacts Jihadist platform migration. CREST report. Retrieved from https://crestresearch.ac.uk/resources/how-telegram-disruption-impacts-jihadist-platform-migration/

- Argentino, M.-A., & Amarasingam, A. (2021). They got it all under control: QAnon, conspiracy theories, and the new threats to Canadian national security. In L. West, T. Juneau, & A. Amarasingam (Eds.), Stress tested: The COVID-19 pandemic and Canadian national security (pp. 15–32). Calgary: University of Calgary Press.

- Barkun, M. (2003). A culture of conspiracy: Apocalyptic visions in contemporary America. Berkley: University of California Press.

- Bartholomew, R. (2020, August 23). A note on the save the children protests. Bartholomew’s notes on religion. Retrieved January 21, 2022, from https://barthsnotes.com/2020/08/23/a-note-on-save-the-children-protests/

- Butter, M. (2020). The nature of conspiracy theories. Translated by Sharon Howe. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Cooper, W. M. (1991). Behold, A Pale Horse. Flagstaff, AZ: Light Technology Publishing.

- Festinger, L., Riecken, H., & Schachter, S. (1964/1965). When prophecy fails: A social and psychological study of a modern group that predicted the destruction of the world. New York, NY: Harper and Row.

- Foucault, M. (1966/1970). The order of things: An archaeology of the human sciences. London, UK: Tavistock.

- Gramsci, A. (1999). The Antonio Gramsci reader: Selected writings, 1916-1935. (D. Forgacs, Edited by). London, UK: Lawrence & Wishart.

- Hammer, O. (2001). Claiming knowledge: Strategies of epistemology from theosophy to the new age. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

- Kuhn, S. T. (1964). The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Latour, B. (1993). We have never been modern. Harlow, UK: Pearson Education Ltd.

- Latour, B., & Woolgar, S. (1979). Laboratory life: The construction of scientific facts. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Lawrence, D., & Davis, G. (2020). QAnon in the UK: The birth of a movement. London, UK: Hope not Hate.

- Maton, K. (2003). Pierre Bourdieu and the epistemic conditions of social scientific knowledge. Space and Culture, 6(1), 52–65. doi:10.1177/1206331202238962

- Robertson, D. G. (2014). Transformation: Whitley Strieber’s paranormal gnosis. Nova Religio, 18(1), 58–78. doi:10.1525/nr.2014.18.1.58

- Robertson, D. G. (2016). Conspiracy theories, UFOs and the new age: Millennial conspiracism. London, UK: Bloomsbury.

- Robertson, D. G. (2018). The counter-elite: Strategies of authority in millennial conspiracism. In A. Dyrendal, D. G. Robertson, & E. Asprem (Eds.), Brill handbook of conspiracy theory and contemporary religion (pp. 234–254). Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

- Robertson, D. G. (2021a). Legitimising claims of special knowledge: Towards an epistemic turn in religious studies. Temenos, 57(1), 17–34. doi:10.33356/temenos.107773

- Robertson, D. G. (2021b). Gnosticism and the history of religions. London, UK: Bloomsbury.

- Rothschild, M. (2021). The storm is upon us: How QAnon became a movement, cult, and conspiracy theory of everything. Brooklyn, NY: Melville House.

- Sardarizadeh, S. (2020). What’s behind the rise of QAnon in the UK? BBC Trending, 13. October 2020. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/blogs-trending-54065470 Retrieved January 21, 2022, from.

- Weber, M. (1964). The theory of social and economic organisation. A.M. Henderson and Talcot Parsons (trans.). New York, NY: Free Press.