Abstract

Prevention and treatment of COPD exacerbations are recognized as key goals in disease management. This randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, multicenter study evaluated the effect of fluticasone propionate/salmeterol 250 mcg/50 mcg (FSC 250/50) and salmeterol 50 mcg (SAL) twice-daily on moderate/severe exacerbations. Subjects received treatment with FSC 250/50 during a one month run-in, followed by randomization to FSC 250/50 or SAL for 52 weeks. Moderate/severe exacerbations were defined as worsening symptoms of COPD requiring antibiotics, oral corticosteroids and/or hospitalization. In 797 subjects with COPD (mean FEV1 = 0.98L, 34% predicted normal), treatment with FSC 250/50 significantly reduced the annual rate of moderate/severe exacerbations by 30.4% compared with SAL (1.10 and 1.59 per subject per year, respectively, p < 0.001), the annual rate of exacerbations requiring oral corticosteroids by 34% (p < 0.001) and the annual rate of moderate/severe exacerbations requiring hospitalization by 36% (p = 0.043). Clinical improvements observed during run-in treatment with FSC 250/50 were better maintained over 52 weeks with FSC 250/50 compared to SAL. Statistically significant reductions in albuterol use, dyspnea scores, and nighttime awakenings and numerical benefits on quality of life were seen with FSC 250/50 compared with SAL. The incidence of adverse events was similar across groups. Pneumonia was reported more frequently with FSC 250/50 compared with SAL (7% vs. 2%). FSC 250/50 is more effective than SAL at reducing the rate of moderate/severe exacerbations. These data confirm the beneficial effect of FSC on the management of COPD exacerbations and support the use of FSC in patients with COPD.

| Abbreviations | ||

| COPD | = | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| FP | = | Fluticasone propionate |

| SAL | = | Salmeterol 50 mcg |

| FSC 250/50 | = | Fluticasone propionate/salmeterol 250 mcg/50 mcg |

| ICS | = | Inhaled corticosteroids |

| NNT | = | Number needed to treat |

| OCS | = | Oral corticosteroids |

| SGRQ | = | St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire |

| TORCH | = | Towards a Revolution in COPD Health |

| TRISTAN | = | TRial of Inhaled STeroids ANd long-acting β2-agonists |

INTRODUCTION

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is an under-recognized chronic lung disease that is associated with significant morbidity and mortality worldwide (Citation[1]) and is the fourth leading cause of death in the United States (Citation[2]). COPD is an inflammatory disease of the airways characterized by progressive airflow limitation with commonly reported symptoms of dyspnea, sputum production, and cough and is associated with frequent exacerbations (Citation[3]).

Exacerbations of COPD, although highly variable in clinical presentation, are generally identified as an acute worsening of symptoms beyond normal day-to-day variation that warrant a change in disease management (Citation[4]). COPD exacerbations are associated with an accelerated deterioration in both lung function and health related quality of life over time (Citation[5],Citation6). Increased exacerbations also lead to hospitalization, with mortality rates of approximately 12–21% one year after a hospitalization and 55% after 5 years (Citation[7], Citation[8]). Important risk factors for COPD exacerbations and exacerbation-related hospitalizations include severe airflow obstruction, advanced age, and a history of prior exacerbations (Citation[9]). In 2007, total costs for COPD were estimated to be $42.6 billion, with 50–75% of costs for services associated with COPD exacerbations (Citation[10], Citation[11]). COPD exacerbations of all severities have a substantial impact on patients who suffer from these and result in significant healthcare expenditures thus, the prevention and treatment of COPD exacerbations are recognized as key goals in COPD disease management (Citation[3], Citation[4]).

Treatment of subjects with COPD with the combination of fluticasone propionate (FP) 500 mcg and salmeterol 50 mcg (SAL) together in a single inhaler (FSC 500/50) twice-daily has been shown to significantly reduce the annual rate of exacerbations in subjects with COPD compared with SAL and placebo (Citation[12],Citation13,Citation14) and also compared with FP 500 mcg (Citation[14]). A replicate of the present 52-week study evaluated a lower dose of FP and SAL (FSC 250/50), and demonstrated that this dose also significantly reduced the annual rate of moderate/severe exacerbations in subjects with COPD compared with SAL (Citation[15]). Previous studies with FSC 250/50 have also demonstrated the benefit of FSC 250/50 twice-daily on measures of lung obstruction and hyperinflation, symptoms, albuterol use and exercise endurance time in COPD (Citation[16],Citation17,Citation18,Citation19).

This was a 52-week clinical study (study code SCO100250, clinicaltrials.gov# NCT00115492) designed to evaluate the effect of FSC 250/50 on moderate/severe COPD exacerbations in subjects with a history of exacerbation(s) and its impact on patient related outcomes. To evaluate the benefit of the inhaled steroid component, FP, of FSC 250/50, SAL was chosen as the comparison arm.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Subjects were ≥ 40 years of age with a diagnosis of COPD (chronic bronchitis and/or emphysema), a cigarette smoking history ≥ 10 pack-years, a pre-albuterol FEV1/FVC ≤ 0.70, a FEV1 ≤ 50% of predicted normal and a documented history of at least 1 COPD exacerbation the year prior to the study that required treatment with antibiotics, oral corticosteroids, and/or hospitalization. Subjects were excluded if they had a current diagnosis of asthma, a respiratory disorder other than COPD, historical or current evidence of a clinically significant uncontrolled disease, or had a COPD exacerbation that was not resolved at screening.

Study design

This was a randomized, double-blind, parallel-group study conducted at 98 research sites in the United States and Canada. For each site, an institutional review board or ethics committee approved the study, and all subjects provided written informed consent prior to conduct of study procedures. Subjects completed a 4-week run-in period during which they received open-label FSC 250/50 via DISKUS® (Advair, Seretide, GlaxoSmithKline, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA) twice daily. The purpose of the run-in with FSC 250/50 was to standardize treatment prior to randomization in an attempt to minimize the likelihood of exacerbations during run-in related to suboptimal therapy.

Following run-in, subjects were randomized to FSC 250/50 or SAL (Serevent; GlaxoSmithKline) twice-daily via DISKUS for 52 weeks. Clinic visits were conducted at screening, day 1 (randomization), and after 4, 8, 12, 20, 28, 36, 44, and 52 weeks of treatment. Treatments were assigned in blocks using a center-based randomization schedule. Since bronchodilator response to FSC 250/50 is generally larger in subjects with COPD who demonstrate FEV1 reversibility to albuterol, assignment to blinded study medication was stratified based on subjects' FEV1 response to albuterol at screening to provide a similar distribution of albuterol-responsive and non-responsive subjects in each treatment group.

Albuterol-responsive was defined as an increase in FEV1 of ≥ 200 mL and ≥12% from baseline following inhalation of four puffs of albuterol. As-needed albuterol was provided for use throughout the study. As needed ipratropium was not provided; however, it could be used during the study. The use of concurrent inhaled long-acting bronchodilators (beta2-agonist and anticholinergic), ipratropium/albuterol combination products, oral beta-agonists, inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), leukotriene modifiers, inhaled nedocromil and cromolyn, theophylline preparations, ritonavir and other investigational medications were not allowed during the treatment period. Oral corticosteroids (OCS) and antibiotics were allowed for the acute treatment of a COPD exacerbation.

Measurements

The primary efficacy endpoint was the annual rate of moderate/severe exacerbations. Secondary endpoints were the time to first moderate/severe exacerbation, the annual rate of exacerbations requiring oral corticosteroids, and pre-dose FEV1. Related endpoints included the annual rate of all exacerbations (mild and moderate/severe), time to onset of each moderate/severe exacerbation, and diary records of dyspnea scores, nighttime awakenings due to COPD, and use of supplemental albuterol. The annual rate of moderate/severe exacerbations analyzed by age, reversibility, smoking status and emphysema only subgroups, the annual rate of moderate/severe exacerbations treated with antibiotics, the annual rate of moderate/severe exacerbations requiring hospitalization, and the annual rate of exacerbations in those with an exacerbation requiring hospitalization in the last 12 months were evaluated as post-hoc measures. Spirometry was obtained using centralized spirometry services provided by the Compleware Corporation (North Liberty, Iowa, United States).

Morning peak flow measurements, nighttime awakenings, albuterol use, and symptom ratings of major and minor symptoms were recorded daily by subjects on paper diary cards. Major symptoms were defined as dyspnea, sputum purulence, and sputum volume, and minor symptoms were defined as cough/wheeze, fever, sore throat, and cold (nasal discharge/congestion). Dyspnea, sputum purulence and volume, and cough/wheeze were evaluated relative to their usual state while others were evaluated based on their absence or presence. Dyspnea was rated using a 5-point scale where −2 = much less than usual, −1 = less than usual, 0 = same as usual, +1 = more than usual, and +2 = much more than usual while sputum purulence and volume, and cough/wheeze were rated using a 2 point scale where 0 = usual level and +1 = increased level.

A COPD exacerbation was defined as worsening of two or more major symptoms or one major and one minor symptom for two or more consecutive days. Moderate/severe exacerbations were defined as worsening respiratory symptoms as described above requiring treatment with antibiotics, oral corticosteroids, and/or hospitalization. Mild exacerbations were defined as worsening respiratory symptoms as described above not requiring treatment with antibiotics or oral corticosteroids. COPD exacerbations were identified based on diary card review and/or based on investigator judgment. Subjects were instructed to contact their study investigator or coordinator if they experienced worsening symptoms of COPD and to report to their study site as required for evaluation. Study investigators assessed the severity of the worsening symptoms to determine the need for additional treatment. If additional treatment beyond blinded study medication or short-acting bronchodilators was required, investigators could treat the exacerbation with a course of antibiotics and/or oral corticosteroids.

The protocol provided the investigators with guidelines for the treatment of exacerbations with antibiotics and oral corticosteroids. Guidelines recommended that courses of antibiotics be 7 to 14 days in duration with provisions allowed for additional courses if first line treatment failed. Use of antibiotics for treatment of upper or lower respiratory tract infections was not considered an exacerbation unless accompanied by worsening symptoms of COPD. Guidelines recommended that courses of oral corticosteroids not exceed 14 days unless given approval by the study sponsor. Any course of antibiotics or oral corticosteroids starting within 7 days of the stop date for a previous course was considered treatment of a single exacerbation.

Health status was evaluated using the St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) administered at randomization, and weeks 12, 28, and 52. Safety was assessed by adverse event reporting.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 8.2 software in a UNIX reporting environment. The sample size calculation for this study (N = 674) provided 90% power to detect a 21% reduction in the rate of moderate/severe exacerbations in the FSC 250/50 treatment group compared with the SAL treatment group at the 0.05 significance level using Poisson regression with an over-dispersion estimate of 1.5 and unadjusted annual exacerbation rate estimates of 1.9 and 1.5 for SAL and FSC 250/50, respectively. The primary analysis of the rate of moderate/severe exacerbations compared treatment groups using a negative binomial regression model with terms for baseline disease severity, pooled investigator, reversibility stratum, treatment group and time on treatment. The negative binomial model incorporates modeling of the variability between subjects in the estimation of exacerbation rates, thereby reducing bias caused by study withdrawals.

Time to first moderate/severe exacerbation was presented graphically with Kaplan–Meier curves and analyzed using a Cox's proportional hazards model with terms for baseline disease severity, pooled investigator, reversibility stratum and treatment group in the model. Time to each moderate/severe exacerbation was compared between treatment groups using an Anderson–Gill model for time to recurrent events.

The primary analysis of pre-dose AM FEV1 was mean change from baseline compared between treatment groups at endpoint. Endpoint was defined as the last scheduled measurement of pre-dose AM FEV1 during the 52-week treatment period and baseline was defined as the pre-dose AM FEV1 measure from day 1 (randomization). An analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model including terms for treatment group, pooled investigator, reversibility stratum and baseline was used to test statistical differences between treatment groups. An ANCOVA model was also used to test statistical differences in treatment group mean changes from baseline for SGRQ scores and for the overall 52-week treatment period for shortness of breath scores, supplemental albuterol use and nighttime awakenings due to COPD.

RESULTS

Subjects

Of the 1288 subjects screened, 797 were randomized of whom 516 (65%) completed the study (). The efficacy and health outcomes data for 19 subjects from two investigational sites were non-evaluable due to non-compliance with ICH guidelines for good clinical practice and were excluded from the analysis. Exclusion of these data did not affect the efficacy analyses. A total of 269 of 394 (68%) subjects in the FSC 250/50 group completed the study compared with 247 of 403 (61%) subjects in the SAL group. The probability of withdrawing from the study at any time was significantly greater in the SAL group compared with FSC 250/50 (p = 0.015).

The most common reasons for withdrawal in the FSC 250/50 and SAL groups were subject decision to withdraw (9% and 11%, respectively) and adverse event (9% and 10%, respectively). Demographic data, smoking history and baseline lung function values, and prior medication use were similar between groups (). Subjects were predominately White (94%) with severe airway obstruction (mean pre-albuterol FEV1 of 34% of predicted normal) and the majority (55%) were using ICS or an ICS/long-acting beta2-agonist combination at screening.

Table 1 Demography and baseline characteristics

COPD exacerbations

The mean annual rate of moderate/severe exacerbations with FSC 250/50 treatment was 1.10 per subject compared with 1.59 per subject with SAL (p < 0.001), corresponding to a treatment ratio of 0.696 (95% CI, 0.58 to 0.83) and a 30.4% reduction (relative risk reduction) in the mean annual rate of exacerbations (). A total of 54% and 60% of subjects experienced at least 1 moderate/severe exacerbation over the duration of the study in the FSC 250/50 and SAL groups, respectively (). Utilizing a number needed to treat (NNT) analysis, a total of two subjects need to be treated for 52 weeks with FSC 250/50 in order to prevent one exacerbation per year.

Table 2 COPD exacerbations

When the primary endpoint was analyzed by age (< 65 and ≥ 65 years), reversibility (non-reversible and reversible), smoking status (current smoker and former smoker) and subjects with emphysema only, the annual rate of moderate/severe exacerbations was statistically significantly lower with FSC 250/50 compared with SAL for all subgroups with the exception of subjects < 65 years of age and current smokers ().

Table 3 Moderate/severe COPD exacerbations by age, reversibility, smoking status, and emphysema (only)

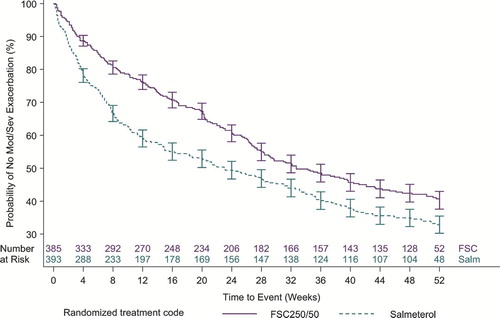

The time to first moderate/severe exacerbation was significantly delayed in subjects treated with FSC 250/50 compared with SAL, with a hazard ratio of 0.73, corresponding to a risk reduction of 27% (95% CI, 0.60 to 0.88, p < 0.001, ). For the mean annual rate of exacerbations requiring oral corticosteroids, the treatment ratio for FSC 250/50 compared with SAL was 0.657, representing a 34.3% reduction with FSC 250/50 treatment (p < 0.001, ). The mean annual rate of moderate/severe exacerbations treated with antibiotics (no OCS) was low and not statistically different between groups (FSC 250/50: 0.28 per subject; SAL: 0.34 per subject). However, FSC significantly reduced the mean annual rate of moderate/severe exacerbations treated with antibiotics with or without OCS, p = 0.021). The mean annual rate of all exacerbations (mild plus moderate/severe) was significantly lower with FSC 250/50 treatment (treatment ratio of 0.83, p = 0.003, ). FSC 250/50 significantly lowered the risk of experiencing recurrent exacerbations by 27% compared with SAL (hazard ratio 0.73, 95% CI 0.62 to 0.86, p < 0.001).

Resource utilization

Treatment with FSC 250/50 also significantly lowered the mean annual rate of moderate/severe exacerbations requiring hospitalization compared with SAL (0.12 vs. 0.19 respectively, p = 0.043), corresponding to a 36% reduction with FSC 250/50 treatment. In addition, subjects with a history of an exacerbation requiring hospitalization in the last 12 months treated with FSC 250/50 had a significantly lower annual rate of moderate/severe exacerbations compared with those taking SAL (1.18 vs. 1.93 respectively, p = 0.004).

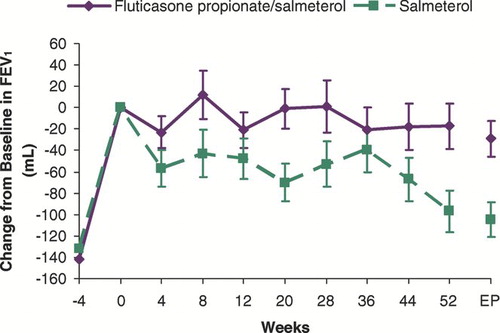

Lung function

Treatment with open-label FSC 250/50 significantly increased mean morning pre-dose FEV1 compared to screening levels (142 ± 16mL and 132 ± 15mL, in subjects subsequently randomized to FSC 250/50 and SAL, respectively, p < 0.001 for within group change from screening, ). Throughout the study, treatment with FSC 250/50 resulted in a preservation of lung function compared with SAL, although following randomization, pre-dose FEV1 decreased over the 52-week treatment period in both groups. When compared to within group treatment day 1 baseline, the decrease in FEV1 was not statistically different in subjects treated with FSC 250/50 (−17 ± 21 mL, p = 0.415); however, a statistically significant decrease was observed in subjects treated with SAL (−97 ± 20 mL, p < 0.001). Mean differences in pre-dose FEV1 of 70 ± 21 mL and 84 ± 26 mL at endpoint and week 52, respectively, significantly favored FSC 250/50 over SAL (p = 0.001).

Supplemental albuterol use

Mean baseline use of supplemental albuterol was 4.5 ± 0.22 and 4.6 ± 0.22 puffs per day for subjects randomized to FSC 250/50 and SAL, respectively. Over weeks 1–52, SAL-treated subjects had a significantly larger mean increase in supplemental albuterol use (0.7 ± 0.10 puffs/day) compared with FSC 250/50 treated subjects (0.3 ± 0.12 puffs/day, p = 0.010), representing an 8.5% reduction in albuterol use in FSC 250/50 treated subjects compared with SAL.

Patient-related outcomes

Consistent with less supplemental albuterol use for FSC 250/50 treated subjects, increases in dyspnea scores were also significantly less with FSC 250/50 compared with SAL. Diary dyspnea scores increased by 0.10 ± 0.03 and 0.19 ± 0.03 units over weeks 1–52 with FSC 250/50 and SAL, respectively, representing a mean difference of 0.08 ± 0.03 units, p = 0.008).

The a priori analysis of nighttime awakenings due to COPD was for the subset of symptomatic subjects who reported at least one nighttime awakening during the 7 days prior to randomization. At baseline, 124 (32%) and 145 (37%) subjects in the FSC 250/50 and SAL groups, respectively, reported a nighttime awakening due to COPD with mean values of 6.93 ± 0.57 and 7.00 ± 0.53 awakenings per week. FSC 250/50 treatment significantly decreased the mean number of nighttime awakenings by 0.91 ± 0.36 awakenings per week compared with an increase of 0.21 ± 0.39 awakenings per week in the SAL group, representing a reduction of more than 1 nighttime awakening per week in FSC 250/50 treated subjects (mean difference of −1.12 awakenings per week, p = 0.032).

Treatment with FSC 250/50 resulted in a numerically smaller decline in quality of life compared with SAL. There was a worsening in mean SGRQ total score from baseline to endpoint of 2.49 units in the FSC 250/50 group compared to 3.28 units in the SAL group (mean difference of −0.81 units, p = 0.371). The change from baseline in SGRQ score favored FSC 250/50; however the mean difference in score between groups did not meet the threshold of 4 units defined as a clinically meaningful change (Citation[20]). Over a period of 52-weeks neither treatment group reached a 4-unit worsening in SGRQ score. Mean differences between FSC 250/50 and SAL for domain scores were −3.37 ± 1.46 for symptoms (p = 0.021), −1.89 ± 1.00 for impacts (p = 0.058), 0.46 ± 1.07 for activity (p = 0.666).

Safety

Overall, adverse events were reported for a similar percentage of subjects in the FSC 250/50 (87%) and SAL (85%) groups. The most common adverse events across both groups were nasopharyngitis and pharyngolaryngeal pain, which occurred in a similar percentage of subjects in each group (33% to 34% of subjects). Adverse events that occurred in greater than 5% of subjects in any group are reported in .

Table 4 Adverse events reported for > 5% of subjects

A total of 21% and 18% of subjects experienced non-fatal serious adverse events in the FSC 250/50 and SAL groups, respectively. The most common serious adverse event was worsening COPD which occurred in 9% of subjects in both the FSC 250/50 and SAL groups. There were 4 deaths in the FSC 250/50 group and 6 deaths in the SAL group. All deaths were considered not related to study medication by the investigators.

Pneumonia (which per protocol was to be confirmed by chest X-ray) was more commonly reported in the FSC 250/50 group, reported in 26 (7%) subjects treated with FSC 250/50 compared with 10 (2%) subjects in the SAL group. Serious adverse events of pneumonia were experienced by 13 (3%) and 8 (2%) subjects in the FSC 250/50 and SAL groups, respectively. There were no pneumonia-related deaths in either treatment group.

Adverse events of dysphonia and candidiasis-related events were reported for a larger percentage of subjects in the FSC 250/50 group (5% and 6%, respectively) than in the SAL group (1% and < 1%, respectively). The incidence of eye and bone disorders was low (< 1–4%) and reported for a similar number of subjects in both treatment groups.

DISCUSSION

This study confirms that treatment with FSC 250/50 for 52 weeks significantly reduces the annual rate of moderate/severe COPD exacerbations. FSC 250/50 reduced the annual rate of moderate/severe exacerbations by 30.4% compared with SAL, corresponding to a NNT analysis that requires two subjects be treated with FSC 250/50 for 52 weeks in order to prevent one exacerbation. The findings for the primary endpoint were supported with secondary endpoints that showed a significantly lower annual rate of COPD exacerbations requiring oral corticosteroids, a significantly delayed time to first moderate/severe exacerbation with FSC 250/50 and greater maintenance of pre-dose FEV1 compared with SAL. In addition, the benefit of FSC 250/50 on moderate/severe exacerbations translated to a significantly lower annual rate of moderate/severe COPD exacerbations requiring hospitalization, dyspnea symptoms, nighttime awakenings and supplemental albuterol use compared with SAL.

Several studies have shown treatment with FSC 250/50 and 500/50 results in greater improvement in lung function as measured by FEV1 compared with SAL, FP and placebo in subjects with COPD (Citation[12], Citation[14], Citation[16], Citation[19], Citation[21]). The 3-year Towards a Revolution in COPD Health (TORCH, Survival Study) showed FSC 500/50 treatment resulted in a lower risk of all cause mortality compared with placebo (hazard ratio 0.825 compared with placebo over three years, p = 0.052) and reduced the rate of decline of FEV1 (Citation[14], Citation[22]). This same study showed FSC 500/50 significantly reduced the annual rate of moderate or severe COPD exacerbations compared with FP, SAL, and placebo (p ≤ 0.02). Similar reductions in the annual rate of COPD exacerbations were observed in the 12-month TRial of Inhaled STeroids ANd long-acting ß2-agonists (TRISTAN) study for comparisons of FSC 500/50 with FP, SAL, and placebo (Citation[12]). In a study of COPD subjects with somewhat more severe disease than in TORCH or TRISTAN, FSC 500/50 treatment significantly reduced the rate of moderate and severe exacerbations by 35% compared with SAL (p < 0.001) (Citation[13]). The results of the current study confirm the findings of a replicate study published by Ferguson and colleagues (Citation[15]). Both studies demonstrated significant reductions in the annual rate of moderate/severe exacerbations compared with SAL, extending the beneficial effect of reduced exacerbations with FSC 250/50.

This study included a 4-week run-in period in which all subjects were treated with FSC 250/50 prior to randomization, resulting in withdrawal of FP for subjects randomized to SAL. The purpose of the run-in with FSC 250/50 was to standardize treatment prior to randomization in an attempt to minimize the likelihood of exacerbations during run-in related to suboptimal therapy. Previous studies have shown that withdrawal of an inhaled corticosteroid has been associated with an increase in exacerbation rate (Citation[23], Citation[24]). A rapid separation between treatment arms for time to first moderate/severe exacerbation occurred early in this study indicating an increased risk of exacerbation following FP withdrawal. Importantly, the difference between treatments in the probability of experiencing an exacerbation remained consistent throughout the study demonstrating that the effect of decreasing the probability of COPD exacerbations with FSC 250/50 compared with SAL was maintained throughout one year of treatment.

Additional analyses support that the lower exacerbation rates with FSC 250/50 were not simply due to an ICS withdrawal effect at the start of the study. When data from the first 4 or 8 weeks are excluded (those exacerbations more likely to be due to ICS withdrawal), the annual rate of moderate/severe exacerbations was still significantly lower with FSC 250/50 compared with SAL (treatment rate ratios of 0.758, p = 0.003 and 0.794, p = 0.020, respectively). In addition, data from the TORCH study demonstrated significant reductions in the annual rate of moderate/severe exacerbations with FSC 500/50 compared with both FP and SAL, indicating that both components contribute to the beneficial effects on exacerbations (Citation[14]).

In addition to being a major cause of chronic disability, COPD is a driver of significant health care service use. The disease results in both high direct and high indirect costs, and exacerbations of COPD account for the greatest burden on the health care system (Citation[4]). The reductions in the annual rate of moderate/severe exacerbations requiring hospitalization and the annual rate of moderate/severe exacerbations in subjects with a history of an exacerbation requiring hospitalization in the last 12 months seen with FSC 250/50 could translate into significant reductions in the burden of COPD on the health care system.

Consistent with the benefical effect on COPD exacerbations, treatment with FSC 250/50 resulted in signifcant reductions in albuterol use, dyspnea scores and nighttime awakenings compared with SAL. Although changes in quality of life favored FSC 250/50, differences between groups did not meet the threshold of 4 units defined as a clinically meaningful difference (Citation[20]). However, the SGRQ was not measured at screening so it is unclear what impact the 4-week run-in period with FSC 250 had on quality of life. In addition, quality of life may not be the best measure of the impact of FSC 250/50 on exacerbations of COPD as the SGRQ was only measured at certain study visits and may not reflect what was happening at the time of an exacerbation of COPD. However, over 52-weeks neither group reached a 4-point worsening in quality of life.

The incidence of reported pneumonia-related events was higher in the FSC 250/50 group (7%) compared with the SAL group (2%). A similar incidence of reported pneumonia-related events was seen in the replicate study by Ferguson and colleagues (Citation[15]) with FSC 250/50. Furthermore, these findings are consistent with results of previous studies of 1 to 3 years showing an increased incidence of reported pneumonias with use of FSC 500/50 and FP 500 twice-daily for COPD when compared with SAL and placebo (Citation[13], Citation[14]). However, in all of these studies, the increased incidence of pneumonia with FSC did not appear to be associated with an increased incidence of serious adverse events or deaths.

The clinical presentation of COPD exacerbations and pneumonia (i.e. increased dyspnea, increased sputum volume and increased sputum purulence) are similar; however the relative incidence of COPD exacerbations are much higher compared to the incidence of pneumonia, as illustrated in the current study with 54–60% of subjects with at least 1 moderate/severe COPD exacerbation as compared to 2–7% of subjects with a reported pneumonia-related adverse event. As the relative incidence of moderate/severe COPD exacerbations is considerably more frequent than adverse events of pneumonia, the significant reduction in moderate/severe exacerbations supports an overall positive risk benefit profile. A recent retrospective population-based cohort study has suggested that, as a class, ICS use in subjects with COPD may be associated with an increased risk of hospitalization for pneumonia (Citation[25]). It is unclear if pneumonia is a dose related phenomenon, as no studies have directly compared the incidence of pneumonia between FSC 500/50 and FSC 250/50. However, the rates of pneumonia when corrected for exposure are very similar between the two doses.

The incidence of known local side effects of ICS such as oral candidiasis and dysphonia occurred more frequently with FSC 250/50 than SAL. Systemic effects of FSC 250/50 were not apparent based on a similar incidence of adverse events related to eye and bone disorders in the FSC 250/50 and SAL groups, consistent with findings from a 3-year study with FSC 500/50 which demonstrated no differences in bone mineral density or in the number of cataracts compared with the placebo group (Citation[14]).

In summary, this study demonstrates that long-term treatment with FSC 250/50 results in a significantly lower annual rate of moderate/severe exacerbations compared with the long-acting bronchodilator SAL in COPD subjects with a history of exacerbation(s). Furthermore, decreasing the frequency of exacerbations translated into significant improvements in subject-related outcomes and hospitalizations. Additionally, a higher incidence of reported pneumonia was observed with FSC 250/50 compared with SAL. Given that COPD exacerbations are associated with significant morbidity, mortality and healthcare expenditures, these data provide further evidence to support the beneficial effect of FSC on the management of COPD exacerbations and support the use of FSC in patients with COPD.

Declaration of interests

This study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline. These data have been presented in part at the 2008 Annual meeting of the American Thoracic Society in Toronto, Canada. Dr. Anzeuto is a member of the GOLD Executive and Scientific Committees and supports the implementation of the GOLD guideline recommendations; has received honoraria and consulting fees from Bayer-Schering Pharma, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sepracor, Schering-Plough Corporation, Dey and Ortho-McNeil; and has been paid for participating in multi-center clinical trials sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer-Schering Pharma, BARD, Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline and NIH. Dr. Ferguson has received honoraria and consulting fees from GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, Novartis and Pearl Therapeutics; has received an investigator initiated research grant from GlaxoSmithKline; and has been paid for participating in multi-center clinical trials sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Emphasys, Dey, Forrest, Altana and Mannkind. Dr. Feldman has been paid for participating in a multi-center clinical trial sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Chinsky has received honoraria and consulting fees from GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim and Sepracor; and has been paid for participating in multi-center clinical trials sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Seibert has been paid for participating in a multi-center clinical trial sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline. Amanda Emmett is an employee of GlaxoSmithKline and owns stock in the company. Dr. Knobil is an employee of GlaxoSmithKline and owns stock in the company. Dr. O'Dell is an employee of GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Kalberg is an employee of GSK and owns stock in the company. Dr. Crater is an employee of GlaxoSmithKline and owns stock in the company.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors acknowledge the editorial assistance of Tracy Fischer and Andrea Morris in the development and author review of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Pauwels R A, Rabe K F. Burden and clinical features of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Lancet 2004; 364: 613–620

- National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Morbidity and mortality: 2007 chart book on cardiovascular, lung, and blood diseases, Available at: www.nhlbi.nih.gov/resources/docs/cht-book.htm Accessed June 19, 2008

- Celli B R, Mac Nee W, ATS/ERS Task Force. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J 2004; 23: 932–946

- Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of COPD. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). 2006, Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org

- Donaldson G C, Seemungal T A, Bhowmik A, et al. Relationship between exacerbation frequency and lung function decline in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 2002; 57: 847–852

- Seemungal T A, Donaldson G C, Paul E A, et al. Effect of exacerbation on quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998; 157: 1418–1422

- McGhan R, Radcliff T, Fish R, et al. Predictors of rehospitalization and death after a severe exacerbation of COPD. Chest 2007; 132: 1748–1755

- Soler-Cataluña J J, Martínez-García M A, Román Sánchez P, et al. Severe acute exacerbations and mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 2005; 60(11)925–931

- Niewoehner D E, Lokhnygina Y, Rice K, et al. Risk indexes for exacerbations and hospitalizations due to COPD. Chest 2007; 131: 20–28

- American Lung Association. Trends in chronic bronchitis and emphysema: morbidity and mortality. December, 2007, www.lungusa.org. Accessed June 20, 2008

- American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society. Standards for the diagnosis and management of patients with COPD [Internet]. Version 1.2, www.thoracic.org/go/copd Accessed June 20, 2008

- Calverley P, Pauwels R, Vestbo J, et al. Combined salmeterol and fluticasone in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2003; 361: 449–456

- Kardos P, Wencker M, Glaab T, et al. Impact of salmeterol/fluticasone propionate versus salmeterol on exacerbations in severe chronic obstructive disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007; 175: 144–149

- Calverley P M, Anderson J A, Celli B, et al. Salmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2007; 356: 775–789

- Ferguson G T, Anzueto A, Fei R, et al. Effect of fluticasone propionate/salmeterol (250/50 mcg) or salmeterol (50 mcg) on COPD exacerbations. Resp Med 2008; 102(8)1099–1108

- Hanania N A, Darken P, Horstman D, et al. The efficacy and safety of fluticasone propionate (250 mcg)/salmeterol (50 mcg) combined in the DISKUS inhaler for the treatment of COPD. Chest 2003; 124: 834–843

- Donohue J F, Kalberg C, Emmett A, et al. A short-term comparison of fluticasone propionate/salmeterol with ipratropium bromide/albuterol for the treatment of COPD. Treat Respir Med 2004; 3: 173–181

- Make B, Hanania N A, ZuWallack R, et al. The efficacy and safety of inhaled fluticasone propionate/salmeterol and ipratropium/albuterol for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: An eight-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, parallel-group study. Clin Ther 2005; 27: 531–542

- O'Donnell D E, Sciurba F, Celli B, et al. Effect of fluticasone propionate/salmeterol on lung hyperinflation and exercise endurance in COPD. Chest 2006; 130: 647–656

- Jones P W, Quirk F H, Baveystock C M, et al. A self-complete measure for chronic airflow limitation, the St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire. Am Rev Respir Dis 1992; 145: 1321–1327

- Mahler D A, Wire P, Horstman D, et al. Effectiveness of fluticasone propionate and salmeterol combination delivered via the Diskus device in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002; 166: 1084–1091

- Celli B R, Thomas N E, Anderson J A, et al. Effect of pharmacotherapy on rate of decline of lung function in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease results from the TORCH Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008; 178: 332–338

- Van Der Valk P, Monninkhof E, Van Der Palen J, et al. Effect of discontinuation of inhaled corticosteroids in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the COPE study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002; 166: 1358–1363

- Wouters E F, Postma D S, Fokkens B, et al. Withdrawal of fluticasone propionate from combined salmeterol/fluticasone treatment in patients with COPD causes immediate and sustained disease deterioration: a randomised controlled trial. Thorax 2005; 60: 480–448

- Woodhead M. Inhaled corticosteroids cause pneumonia … or do they?. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007; 176(2)111–112