Abstract

The increasing prevalence and incidence of bronchiectasis leads to a substantial health care burden. Quality standards for the management of bronchiectasis were formulated by the British Thoracic Society following publication of guidelines in 2010. They can be used as a benchmark for quality of care. It is, however, unclear how and whether they apply outside of the UK. Between May and November 2017, we conducted an online survey among respiratory physicians caring for adult bronchiectasis patients in Belgium. About 186 cases were submitted by 117 treating physicians. Patients were mostly female (58%), of Caucasian descent (84%) with a remarkably low median age of 59.8 (IQR 47–73) years. 41% had Pseudomonas aeruginosa, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and/or Enterobacteriaceae isolated from respiratory samples in the past. 21% had three or more exacerbations, however, more than 58% were receiving long-term oral antibiotics (of which 90% azithromycin). In 40% of patients the diagnostic testing was insufficient. Surveillance of sputum bacteriology in stable patients and composing a self-management plan was missing in 53% and 68% of patients, respectively. Airway clearance techniques were implemented in 84%. Respiratory physicians complied with 60% or more to five out of the eight applicable quality standards, which is encouraging. Increasing educational act could further raise awareness and increase quality of care.

Introduction

Bronchiectasis is a chronic respiratory disease characterized by chronic productive cough and recurrent chest infections (Citation1). The increasing prevalence of bronchiectasis leads to a substantial health care burden (Citation2). To ensure optimal bronchiectasis management, a set of quality standards were developed by the British Thoracic Society (BTS) (Citation3). However, standards of care might not be universally applicable and adherence to it may vary across different countries (Citation4,Citation5). Previously, Aliberti et al. (Citation5) used those quality measures to evaluate bronchiectasis care in Italy since there were no international guidelines at the time (Citation1).

Methods

We conducted a national survey to evaluate specialist adult bronchiectasis care in Belgium against the BTS quality standards and to assess to what extent these apply to the Belgian setting. All members of the Belgian Pulmonology Society were invited by email to complete an electronic case report form, via an online survey platform, based on the medical records of a patient with clinically significant bronchiectasis. Physicians were requested to enter a maximum of three cases to ensure a diverse input and avoid predominance of certain practices. We questioned various aspects related to managing bronchiectasis patients including diagnosis and care in order to evaluate the different quality standards. Study approval was granted by the joint Ethics Committee of the University Hospitals Leuven and the Catholic University Leuven. Informed consent was waived for this was a survey evaluating physician’s practice not including any patient identifiers. Between May 1st and November 1st 2017, a total of 186 cases were submitted by 117 pulmonary physicians (median 1 case per physician).

Results

In line with international studies the majority of patients were female (58%), of Caucasian descent (84%) and median age of 60 (IQR 47–73) years. About 41% of the patients ever had Pseudomonas aeruginosa, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and/or Enterobacteriaceae isolated from a respiratory sample. The majority of the patients had at least one annual exacerbation while 21% had three or more exacerbations/year; 32% had at least one hospital admission/year. The majority of patients received long-term oral antibiotic therapy (58%), most frequently azithromycin (90%). Only six patients used inhaled antibiotics.

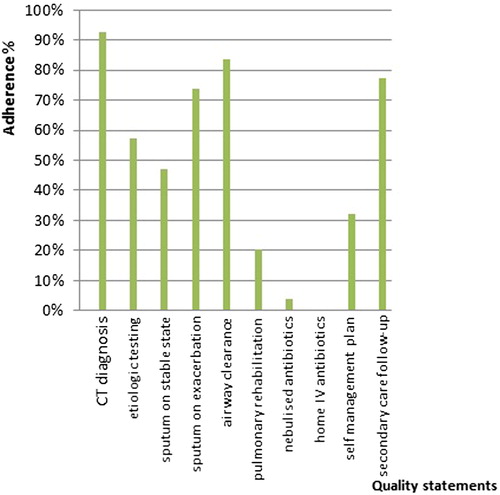

The 2012 BTS quality standards comprise 11 statements (). Results of the survey per statement are shown in .

Figure 1. Summary of quality statements for clinically significant bronchiectasis in adults and percentage adherence in the Belgian audit.

TABLE 1. Quality statements for clinically significant bronchiectasis in adults (adjusted from Hill et al (Citation3)).

The first quality statement recommends confirmation of bronchiectasis by high resolution computed tomography (CT) of the chest. 93% of patients in our survey were diagnosed by CT. Two percent were diagnosed on clinical or chest radiography findings, one by bronchography; 5% this was not specified.

Bronchiectasis can be caused by a wide range of conditions. A specific etiological work-up is recommended by the BTS as a second quality indicator. Patients should be investigated for allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA), common variable immunodeficiency (CVID), and cystic fibrosis (CF) if indicated (second quality statement). In our survey, 84% of the patients had immunoglobulin testing, 62% were tested for ABPA, and 32% had sweat testing and/or CF transmembrane conductance regulator gene mutation analysis. These results are considerably higher than in both previous audits; 63% screening for ABPA, 68% for CVID, and 12% for CF in the British audit (Citation4). In the Italian only 17% were screened for ABPA, 22% for CVID, and 5.5% for CF (Citation5).

The third and fourth statements recommend bronchiectasis patients to have their sputum sent for bacteriology at least once a year when clinically stable, and at the start of an exacerbation, respectively, to allow identification of potentially pathogenic organisms in the airways. Although bronchiectasis is associated with chronic infection by a number of bacteria, P. aeruginosa is clinically the most significant. Its presence is associated with more frequent exacerbations, worse quality of life, faster decline in pulmonary function, increased mortality (Citation6–8).

Sputum culture prior to initiating antibiotics might be useful to guide the choice of antibiotic therapy. In our survey sputum microbiology was performed in 87% of the cases at initial diagnostic work-up. However, only 47% of patients had sputum surveillance cultures recorded in the past year by their respiratory physician. This number is rather low compared to the BTS audit, where 62% had sputum bacteriology when clinically stable. On the contrary, at the start of an exacerbation 73% had sputum microbiology recorded, whereas 53% and 50% had sputum sent in the British and Italian audit, respectively (Citation4,Citation5).

The next quality standard requires bronchiectasis patients to be taught appropriate airway clearance techniques by a specialized respiratory physiotherapist. This statement was met in 84%, which is higher compared with the previous audits.

The sixth statement proposes patients with bronchiectasis who suffer from breathlessness, when affecting their daily activities, to be offered pulmonary rehabilitation. Only 24% of the cases in our survey attended pulmonary rehabilitation services, compared with 32% and 49% in the BTS and Italian survey, respectively (Citation4,Citation5).

The seventh statement requires nebulized antibiotics to be provided for suitable patients, that is, patients with chronic Pseudomonas infection and frequent exacerbations or significant morbidity, but does not apply to our setting. In Belgium inhaled antibiotics are not registered for bronchiectasis because of insufficient evidence of efficacy (Citation9). It is therefore not surprising that long-term oral antibiotics (i.e., azithromycin) are frequently prescribed. Moreover, macrolides are one of the few drugs for which there is evidence from randomized controlled trials for its use in bronchiectasis (Citation10–12).

Home intravenous antibiotic services for exacerbations are suggested for selected patients (8th statement). This reduces the number of hospital bed days and hospital acquired infections (Citation13). In times of hospital bed pressure and increasing numbers of nosocomial infections the benefits of home intravenous therapy seem obvious. Unfortunately, this service is not yet available in Belgium because of lack of reimbursement and health care organizational issues.

The ninth statement advises bronchiectasis patients to have an individualized written self-management plan. The aim is to increase self-awareness of their condition and to recognize, respond, and reduce the occurrence of exacerbations (Citation14). About 32% of patients have a self-management plan, which compares high to other audits (Citation4,Citation5). It empowers patients by discussing disease status and management actions; whether a written action plan makes a difference in outcome has to be proven.

Finally, the 10th statement recommends bronchiectasis patients with advanced disease, frequent exacerbations, associated comorbidities, difficult colonizing micro-organisms to be managed in secondary care by a multidisciplinary team led by a respiratory physician. The rationale being that those patients often have a complicated clinical course which requires specialized management. In our survey, 96% of all patients were being followed by a respiratory physician but not necessarily by a multidisciplinary team. Of those attending secondary care, 76% were seen every 3–6 months, 15% annually. Numbers are higher than in the other two audits and likely reflect differences in health care systems (Citation4,Citation5).

Conclusions

This survey illustrates how bronchiectasis patients are currently managed in Belgium according to the 2012 BTS quality standards of care. It is reassuring that the obtained data are consistent with the European Bronchiectasis Registry data for Belgium (Citation15). The BTS quality standards have now been tested in three countries. Although direct comparison is not possible because of different survey methodology, one can conclude that it exposes the heterogeneity in practice for a similar condition, which may largely be a reflection of the different organization of health care in those three countries. Following the recent dissemination of the first international bronchiectasis diagnosis and management guidelines, one can only hope that the care for bronchiectasis patients will further improve. In this respect, a repeat assessment in a few years’ time might be worthwhile.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Belgian Pulmonology Society (BVP/SBP) and all its members for their support and participation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Polverino E, Goeminne PC, McDonnell MJ, Aliberti S, Marshall SE, Loebinger MR, Murris M, Canton R, Torres A, Dimakou K, et al. European Respiratory Society guidelines for the management of adult bronchiectasis. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(3):1700629.

- Ringshausen FC, de Roux A, Pletz MW, Hämäläinen N, Welte T, Rademacher J. Bronchiectasis-associated hospitalizations in Germany, 2005–2011: a population-based study of disease burden and trends. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e71109.

- Hill AT, Bilton D, Brown J. BTS quality standards for clinically significant bronchiectasis in adults. Br Thorac Soc Rep. 2012;4:1–16.

- Hill AT, Routh C, Welham S. National BTS bronchiectasis audit 2012: is the quality standard being adhered to in adult secondary care? Thorax. 2014;69(3):292–4.

- Aliberti S, Hill AT, Mantero M, Battaglia S, Centanni S, Lo Cicero S, Lacedonia D, Saetta M, Chalmers JD, Blasi F, et al. Quality standards for the management of bronchiectasis in Italy: a national audit. Eur Respir J. 2016;48(1):244–8.

- Blanchette CM, Noone JM, Stone G, Zacherle E, Patel RP, Howden R, Mapel D. Healthcare cost and utilization before and after diagnosis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa among patients with non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis in the U.S. Med Sci. 2017;5(4):E20. doi:10.3390/medsci5040020.

- Arauko D, Shteinberg M, Aliberti S, Goeminne PC, Hill AT, Fardon TC, Obradovic D, Stone G, Trautmann M, Davis A, et al. The independent contribution of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection to long-term clinical outcomes in bronchiectasis. Eur Respir J. 2018;51(2):1701953.

- Finch S, McDonnell MJ, Abo-Leyah H, Aliberti S, Chalmers JD. A comprehensive analysis of the impact of Pseudomonas aeruginosa colonization on prognosis in adult bronchiectasis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12:1602–11.

- Brodt AM, Stovold E, Zhang L. Inhaled antibiotics for stable non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis: a systematic review. Eur Respir J. 2014;44:382–93. doi:10.1183/09031936.00018414.

- Serisier DJ, Martin ML. Long-term, low-dose erythromycin in bronchiectasis subjects with frequent infective exacerbations. Respir Med. 2011;105(6):946–9. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2011.01.009.

- Wong C, Jayaram L, Karalus N, Eaton T, Tong C, Hockey H, Milne D, Fergusson W, Tuffery C, Sexton P, et al. Azithromycin for prevention of exacerbations in non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis (EMBRACE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2012;380(9842):660–7. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60953-2.

- Altenburg J, de Graaff CS, Stienstra Y, Sloos JH, van Haren EH, Koppers RJ, van der Werf TS, Boersma WG. Effect of azithromycin maintenance treatment on infectious exacerbations among patients with non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis: the BAT randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2013;309(12):1251–9. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.1937.

- Anning L, McNeill M, Rose A, Mortimer H, Withers N. The use of home intravenous antibiotics in adult non-CF bronchiectasis. Eur Respir J. 2015;46:PA2626.

- Farrel K, Wicks MN, Martin JC. Chronic disease self-management improved with enhanced self-efficacy. Clin Nurs Res. 2004;13(4):289–308. doi:10.1177/1054773804267878.

- Haworth CS, Johnson C, Aliberi S, Goeminne PC, Ringhausen F, Boersma W, De Soyza A, Murris M, Polverino E, Vendrell M, et al. Management of bronchiectasis in Europe: data from the European bronchiectasis registry (EMBARC). Eur Respir J. 2016;48:OA273. doi:10.1183/13993003.