Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a leading cause of mortality. Since patients with severe COPD may experience exacerbations and eventually face mortality, advanced care planning (ACP) has been increasingly emphasized in the recent COPD guidelines. We conducted a multicenter, cross-sectional study to survey the current perspectives of Japanese COPD patients toward ACP. “High-risk” COPD patients and their attending physicians were consecutively recruited. The patients’ family configurations, understanding of COPD pathophysiology, current end-of-life care communication with physicians and family members, and preferences for invasive life-sustaining treatments including mechanical ventilation (MV) and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) were evaluated using a custom-made, structured, self-administered questionnaire. Attending physicians were also interviewed, and we evaluated the patient–physician agreement. Among the 224 eligible “high-risk” patients, 162 participated. Half of the physicians (54.4%) thought they had communicated detailed information; however, only 19.4% of the COPD patients thought the physicians did so (κ score = 0.16). Less than 10% of patients wanted to receive invasive treatment (MV, 6.3% and CPR, 9.4%); interestingly, more than half marked their decision as “refer to the physician” (MV 42.5% and CPR 44.4%) or “refer to family” (MV, 13.8% and CPR, 14.4%). Patients with less knowledge of COPD were less likely to indicate that they had already made a decision. Although ACP is necessary to cope with severe COPD, Japanese “high-risk” COPD patients were unable to make a decision on their preferences for invasive treatments. Lack of disease knowledge and communication gaps between patients and physicians should be addressed as part of these patients’ care.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a leading cause of mortality worldwide (Citation1, Citation2). Although COPD is defined as a treatable and preventable disease per the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) (Citation2), the disease trajectory of COPD is marked by a gradually declining health status with increasing symptoms punctuated by acute exacerbations and eventual mortality (Citation2). Since these patients may be elderly and have various comorbidities, such as malignancy or severe cardiovascular diseases (Citation1, Citation2), they may prefer to receive palliative care rather than intensive treatment. In such situations, advanced COPD patients and their families must decide which treatment they prefer, and their attending (or emergency room) physicians must consider how to treat these patients. The importance of early patient–physician communication regarding end-of-life care, also known as advance care planning (ACP), has become increasingly recognized. Because ACP has been reported to improve end-of-life care as well as patient and family satisfaction (Citation3–5), ACP has been emphasized in recent COPD guidelines (Citation2).

To achieve patient-centered care and ACP, physicians must actively engage patients and communicate with them regarding their current concerns, aims in life, disease status, future outlook, and treatment options (Citation6,Citation7). These processes are known as shared decision-making (SDM) and enable patients who are at fateful health crossroads to reach optimal decisions (Citation8).

Though ACP is important for severe COPD patients, no reports are available on COPD patient perspectives regarding end-of-life care in Asian countries (Citation9–11). Studies on ACP have been conducted only in Western countries (Citation12–15). Several reports show cultural and regional differences between western and Asian countries regarding end-of-life care in intensive care unit settings (Citation16).

We hypothesized that COPD patients in Japan have different perspectives on end-of-life than patients in western countries. Therefore, we surveyed Japanese COPD patients’ current perspectives toward ACP to determine the optimal therapeutic interventions for COPD patients and their families in Japan. Finally, we addressed the perception discrepancies on end-of-life communication between physicians and patients.

Methods

Study design

This study was a multicenter, cross-sectional survey that used original questionnaires. The survey was conducted at five hospitals in Japan, including one university hospital and four local core hospitals. The ethics committee at Kyoto University (approval No. E1663) and each hospital approved this study protocol, and all patients provided written informed consent to participate in this study.

Participants

Patients over 60 years of age with COPD who regularly visited outpatient clinics at the hospitals listed in Supplementary Table S1 from October 2013 to February 2015 were consecutively recruited (Supplementary Table S1). The patient medical records were screened, eligible patients were enrolled. Their attending physicians were also investigated using specific questionnaires.

Table 1. Patient characteristics (n = 160).

COPD was diagnosed according to the criteria of the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease strategy document (Citation2). The medical records of all consecutive patients who regularly visited the hospitals were screened, and those who met at least one of the following criteria for “high-risk” COPD patients were enrolled in this study: (a) severe airflow limitation, %FEV1 < 50%; (b) increased age, over 75 years of age; (c) hypoxia, with long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT); (d) frequent exacerbator, two or more exacerbations or hospitalized with exacerbations within the last year; or (e, f) frailties, physical deterioration and dependence on someone in daily life. The exclusion criteria are shown in Supplementary Appendix S1.

Measurements

Data on the patients, including age, were collected from their medical records, such as sex, anthropometric measurements, smoking history, comorbidity (Citation17), prescriptions, use of LTOT, use of social resources, pulmonary function, and exacerbation/hospitalization frequency over the past year.

Family configurations, comprehension of COPD pathophysiology, current opinions about end-of-life care communication with physicians and family members, and preferences for invasive life-sustaining treatments were evaluated using a custom-made, structured, self-administered questionnaire (Supplementary Appendices S1). The questionnaire assessed participants’ COPD comprehension and consisted of 10 questions to determine their knowledge of COPD (). The number of correct answers was scored (0–9). In the questionnaire on invasive life-sustaining treatment preferences, participants were asked to choose one option from the following: (1) wish, (2) do not wish, (3) refer to physician, (4) refer to family, or (5) do not know. Furthermore, the participants were asked about their plans for end-of-life care communication with their physicians and family members.

We also interviewed the attending physicians using a custom-designed, self-administered questionnaire (Supplementary Appendix S1) to evaluate the attending physician’s communication with the patients.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the JMP 10 software (SAS institute, Cary, NC). Categorical variables were described as frequencies, and continuous variables were presented as the mean ± SD. Nominal variables were compared using the Chi-square test. Paired patient–physician responses were compared using unweighted κ scores (Citation18).

The patients were dichotomized in the subsequent analyses according to each answer. Answers “wish” or “do not wish” were classified into the “decision made” cohort, whereas other answers were classified as “not yet”. The influence of patient characteristics on their preferences and hopes was determined using univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses. The multivariate analyses included items significantly related (p < 0.05) to decisions made regarding MV or CPR in the univariate analyses (Supplementary Table S3). The results were expressed as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A two-sided level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

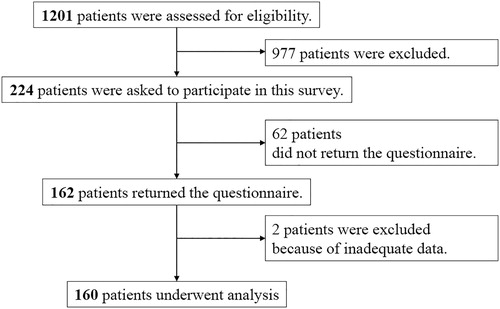

During the study period, 1201 COPD patients were scheduled to visit pulmonary clinics at the hospitals listed in Supplementary Table S1. All patients were diagnosed and treated by pulmonologists, and 224 patients were eligible for the study. All eligible subjects were handed the study questionnaires from their attending physicians, and 162 patients (72.3%) agreed to participate in the study and returned the questionnaire. Since two subjects were excluded due to inadequate data, 160 subjects were analyzed in this study (; ). None of the patients expressed distress or anxiety or visited a psychiatric clinic after answering the questions. Patients who were recruited met one or more of the following criteria: increased age (68.1%), severe airflow limitation (56.9%), hypoxemia (20.6%), frailties (15.6%), and frequent exacerbator (13.5%).

Figure 1. Study flowchart. During the study period, 1201 COPD patients were scheduled for visits to regional hospitals, and 224 patients were eligible for the study. One hundred sixty-two patients returned the questionnaire. Two subjects were excluded due to inadequate data; thus, 160 subjects were analysed in the study.

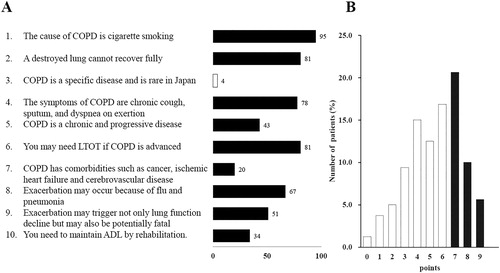

shows the patients’ comprehension of COPD. The average comprehension score for COPD was 5.4 ± 2.1 (max 9). Since the mean ± SD was 7.5, patients with scores ≥7 were classified as having a “good understanding of COPD” (n = 58, 36.3%) ().

Figure 2. Patients’ comprehension of COPD. (A) Score distribution of patients’ comprehension of COPD. COPD patients were asked these questions to investigate their knowledge of COPD pathology. The score represents the percentages of participants who answered “yes”. Item 3 is a trick question to correct for responders who check off all the questions. (B) Total score distribution of COPD comprehension. The filled bars represent good COPD comprehension (≥7).

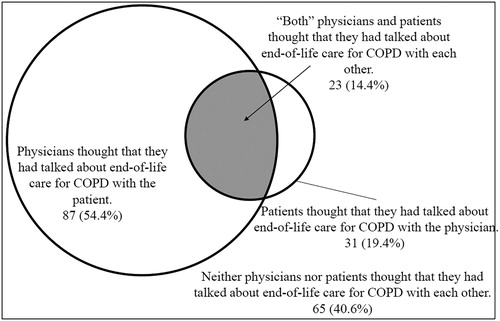

More than half the physicians (54.4%) thought that they had provided detailed information to their COPD patients in advance (; Supplementary Table S2). However, only 19.4% of the COPD patients thought they had communicated with their doctors, and only 14.4% of the patient–physician pairs thought that they both had discussed ACP with each other, with very low agreement (κ score = 0.16; 95% CI 0.046–0.28). No significant trend was found for agreements in past communication. Notably, 26.9% of the COPD patients thought that they had communicated with their family members, reflecting a higher percentage than that for communication with the doctor.

Figure 3. Past communication status about end-of-life care of COPD. Venn Diagram showing past communication status about end-of-life care. More than half of the physicians (54.4%) thought that they had provided detailed information to their COPD patients in advance (left). However, only 19.4% of the COPD patients thought they had communicated with their doctor about these topics (right). Only 14.4% of the physicians-patient pairs thought that they had rigorously discussed these issues with each other (overlapped).

Table 2. Multivariate analysis of patients’ decisions regarding MV and CPR.

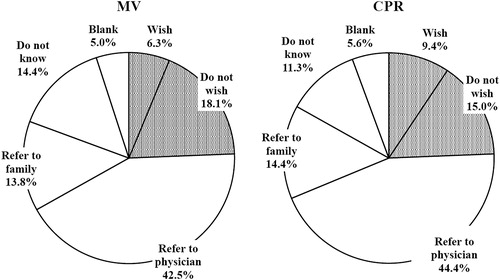

As shown in , less than 10% of the patients wanted to receive invasive treatment (MV, 6.3% and CPR, 9.4%). Moreover, many more patients indicated they wanted to receive no invasive treatment (MV, 18.1% and CPR, 15.0%). Interestingly, more than half the patients presented their decision as “refer to the physician” (MV, 42.5% and CPR, 44.4%) or “refer to family” (MV, 13.8% and CPR, 14.4%) and indicated that they had not reached a decision pertaining to their hopes for invasive treatment in the future.

Figure 4. Patients’ preferences regarding invasive life-sustaining treatments. Only 18.1% of patients wanted MV and 15.0% wanted CPR. The shaded parts represent the “decision made” cohort who answered “wish” or “do not wish”.

In the comparison of patient characteristics with patients’ decisions, the likelihood of having made a decision about MV (“decision made”) was significantly associated with previous malignancy, self-care dependency, and a good understanding of COPD (Supplementary Table S3). A decision made for CPR was significantly associated with previous malignancy and a good understanding of COPD. In the multivariate analysis, only a good understanding of COPD was significant for “decision made” for both MV and CPR (OR, 2.20 and 2.99, respectively) ().

In a univariate analysis of the patients’ hopes for future communication (Supplementary Appendix S2 and Table S4), the patients’ hopes were associated with a good understanding of COPD and past communication. However, our follow-up investigation of the medical records indicated that only 26.9% of the patients had communicated about end-of-life care in the subsequent 6 months. Communication status in the follow-up periods was significantly associated with a good understanding of COPD (OR = 2.46, p < 0.05).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study constitutes the first comprehensive survey concerning Asian COPD patients’ end-of-life perspectives (Citation10). We found that 15–18% of patients indicated that they were unwilling to receive invasive treatments, whereas less than 10% of patients indicated that they did want to receive such treatments. Interestingly, more than half of the patients had not definitively decided about their end-of-life care, instead answering “refer to the physician” or “refer to family”. These results might derive from cultural characteristics of Japanese COPD patients, and it is necessary to consider these differences in the application of treatment procedures for severe COPD patients in clinical settings.

The first important finding of this study was that fragile “high-risk” COPD patients understood the cause of COPD, typical symptoms, and final treatment options, such as oxygen (LTOT). However, their understanding of several features of COPD was significantly worse (). These aspects of COPD are important points for understanding end-of-life care for COPD and ACP, and they might be a major reason why only a good understanding of COPD influenced decisions in advance and future plans for communication about end-of-life care (Supplementary Tables SCitation3 and SCitation4). These results on the importance of communication and comprehension suggest that good communication and understanding may facilitate achievement of SDM and ACP in these situations.

A second important finding was a communication gap between the physicians and patients, as reflected by the very low agreement observed (κ score = 0.16) (). Although more than half of the physicians (54.4%) thought that they had provided detailed information to their patients, only one-fifth of the patients (19.4%) thought that they had communicated with their attending physicians. This poor agreement is similar to findings obtained in another study conducted in Japan (Citation19). In addition, the proportion of both physicians and patients who thought that they had not communicated about end-of-life care was 40.6%. The attending physicians may think that such communication is unnecessary when a patient’s condition is not poor. However, our data suggested that 64% of physicians would not be surprised if their patients experienced severe deterioration of the disease within 1 year (Citation20). Therefore, a significant communication barrier exists between physicians and patients, possibly due to cultural or religious factors (Citation21). Compared with malignant patients, patients with slow/chronic progressive diseases may have difficulty communicating with physicians.

A third important finding was that fewer than 10% of the patients agreed to MV and CPR if needed (), which contradicts the findings obtained by Janssen and colleagues in western countries (Citation22). In their study, approximately 70% of severe COPD patients preferred CPR and MV, whereas our study indicated lower preference in COPD patients for invasive life-sustaining treatments. This finding might be consistent with differences in the importance of autonomy in Asian and western countries. For instance, a survey of healthy people in Japan (Citation23) reported that 10% of participants wanted to receive invasive life-sustaining feeding treatments, such as nasal tube feeding, and approximately 70% denied such treatments. A country’s culture and the values of its people are important in determining end-of-life care practices. Typically, patient autonomy is more important in western countries, but familial relationships are stressed more than individual rights in east Asia. This could be mainly because Confucian thought has deeply influenced east Asian culture for thousands of years (Citation24). Even within the same cultural areas, end-of-life treatment practices are diverse between countries. This diversity might be related to differing degrees of westernization, the national healthcare system, economic status, and legal environment. Nevertheless, our data showed that Japanese COPD patients living in west side of Japan did not desire MV and/or CPR treatment. This knowledge might be useful in addressing end-of-life practices in other countries as well as in Japan.

This lower rate of preference for invasive life support reveals a more important issue. Attending physicians “must discuss” the treatment of life-threatening deterioration, such as severe COPD exacerbation, with patients in advance even though these patients may be recalcitrant to discuss impending death. We should bear in mind that “healthy elderly” patients may not have faced their own inevitable end of life, regardless of the reason. In any case, the choices “refer to physician” and “refer to family” reveal this unique attitude of Japanese people.

Regarding the objective of ACP, providing information on COPD pathophysiology and its progressive nature is important to help patients make treatment decisions in advance. Such offers from physicians and subsequent communication are key points for conducting SDM. In SDM, both parties share information: the clinician offers options and describes their risks and benefits, and the patient expresses their preferences and values (Citation25). In this study, we divided the participants into two groups, including those who had made a decision and those who had not made a decision, to focus on the influence of autonomy among Japanese COPD patients. Interestingly, patients with knowledge of COPD were more likely to have decided on how to be treated, emphasizing the importance of ACP and SDM ().

One poor result should be discussed regarding the communication barrier. Half of our patients wanted to communicate with their physicians; however, our follow-up investigation data from the medical records indicated that only one-quarter of the patients had communicated about end-of-life care in the subsequent 6 months. We affirmed that a communication barrier existed between physicians and patients. This represents another ‘communication gap’ between patients and attending physicians. Physician factors, such as lack of experience (Citation11), are possible; however, most physicians included in the present study were well-experienced with more than 10 years in practice (Supplementary Table S1). Therefore, a lack of experience is unlikely. To overcome barriers or gaps in communication, decision aids that can be delivered online, on paper, or by video can efficiently help patients absorb relevant clinical evidence and facilitate their developing and communicating their informed preferences (Citation26).

The present study has several limitations. First, the sample size is small and may be biased due to the recruitment method. We recruited only “high-risk” COPD patients who regularly visited the respiratory specialist clinic at local core hospitals. Most mild COPD patients may be followed by a primary-care physician and may not have received a sufficient explanation of the disease. We enrolled patients from one university hospital and four local core hospitals in the west side of Japan. Since “high-risk” patients may visit core hospitals, we think our study population is appropriate for our purpose. Nevertheless, we should interrogate whether an outpatient clinic was appropriate for an analysis of communication about end-of-life treatment. In fact, this study is an exploratory study, larger study is still required. We also calculated the sample size using data from our present study (Supplementary Information, Appendix S1), and we could estimate that approximately 106 to 178 subjects would be required (Supplementary Appendix S2). Therefore, we can conclude that we had a sufficient sample to find significances in the present study. Second, patients with dementia or cognitive dysfunction could not be eliminated strictly because more elderly/frail patients might have such problems. We did not perform specific tests for cognitive function (Citation27); however, most patients appropriately completed the questionnaire by themselves, and invalid answers were rare and scattered. Third, our original questionnaire did not evaluate the extent and quality of end-of-life care discussions. Therefore, further investigation is required and should include a healthy or a hospitalized population.

Conclusion

More than half of patients had not decided on their preference for invasive treatments in advance, partly because of their lack of knowledge of COPD. Providing more information and communication about COPD may help patients decide their own treatment preferences in advance. The lower rate of unwillingness to receive invasive treatments and the increased rate of reliance on others should be considered as differences between Asian and Western countries on this topic.

Author contributions

Fuseya contributed to the conception and design of the protocol, to the collection and analysis of the data, and to the writing of the manuscript. Muro contributed to the conception and design of the protocol, to the delineation of the hypotheses, to the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, and to the writing the manuscript. S. Sato is responsible for the integrity of the data and contributed to the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data and to the writing the manuscript. A. Sato contributed to the data analysis and manuscript review. Tanimura contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data and revision of the manuscript prior to submission. Hasegawa contributed to the data analysis and manuscript review. Uemasu contributed to the data analysis and manuscript review. Hamakawa contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data and to the revision of the manuscript prior to submission. Takahashi contributed to the protocol design, to the analysis and interpretation of the data and to the editing of the manuscript. Nakayama contributed to the protocol design, to the analysis and interpretation of the data, and to the editing of the manuscript. Sakai contributed to the data collection and manuscript review. Fukui contributed to the data collection and manuscript review. Kita contributed to the data collection and manuscript review. Mio contributed to the data collection and manuscript review. Mishima contributed to the data analysis and supervised the study. Hirai contributed to the data analysis and supervised the study.

Acknowledgements

All the authors wish to acknowledge and would like to thank all the medical staff involved in the management of the patients in clinical practice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Decramer M, Janssens W, Miravitlles M. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2012;379(9823):1341–1351. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60968-9

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD 2019. 2018. [accessed 2018 Dec 11]. Available from: http://goldcopd.org/.

- Leung JM, Udris EM, Uman J, Au DH. The effect of end-of-life discussions on perceived quality of care and health status among patients with COPD. Chest. 2012;142(1):128–133. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2222

- Patel K, Janssen DJA, Curtis JR. Advance care planning in COPD. Respirology. 2012;17(1):72–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2011.02087.x

- Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, Silvester W. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c1345–c1345.

- Emanuel LL, Gunten von CF, Ferris FD. Advance care planning. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9(10):1181–1187. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.10.1181

- Sudore RL, Fried TR. Redefining the “planning” in advance care planning: preparing for end-of-life decision making. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(4):256–261. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-4-201008170-00008

- Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making–pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):780–781. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1109283

- Ueki J, Mishima M, Tatsumi K, Takahashi K, Ishihara H, Kurosawa H, Fujimoto K, Koyama M, Toyama K. The current situation and the perspective of respiratory care in Japanese COPD patients revealed by Japanese White Paper on home respiratory care 2010 COPD subgroup analysis. Eur Respir J. 2011;38(Suppl 55):1249.

- Jabbarian LJ, Zwakman M, van der Heide A, Kars MC, Janssen DJA, van Delden JJ, Rietjens JAC, Korfage IJ. Advance care planning for patients with chronic respiratory diseases: a systematic review of preferences and practices. Thorax. 2018;73(3):222–230. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-209806

- Ecenarro PS, Iguiñiz MI, Tejada SP, Malanda NM, Imizcoz MA, Marlasca LA, Navarrete BA. Management of COPD in End-of-Life Care by Spanish Pulmonologists. COPD. 2018;15(2):171–176. doi: 10.1080/15412555.2018.1441274

- Curtis JR, Wenrich MD, Carline JD, Shannon SE, Ambrozy DM, Ramsey PG. Patients' perspectives on physician skill in end-of-life care: differences between patients with COPD, cancer, and AIDS. Chest. 2002;122(1):356–362. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.1.356

- Au DH, Udris EM, Fihn SD, McDonell MB, Curtis JR. Differences in health care utilization at the end of life among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and patients with lung cancer. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(3):326–331. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.3.326

- Janssen DJA, Spruit MA, Schols JMGA, Cox B, Nawrot TS, Curtis JR, Wouters EFM. Predicting changes in preferences for life-sustaining treatment among patients with advanced chronic organ failure. Chest. 2012;141(5):1251–1259. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-1472

- Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Nielsen EL, Au DH, Patrick DL. Patient-physician communication about end-of-life care for patients with severe COPD. Eur Respir J. 2004;24(2):200–205. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00010104

- Vincent JL. Cultural differences in end-of-life care. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(2 Suppl):N52–N55. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200102001-00010

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8

- Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–174. doi: 10.2307/2529310

- Saito M, Takahashi Y, Yoshimura Y, Shima A, Morita A, Houkin K, Nakayama T, Nozaki K. Inadequate communication between patients with unruptured cerebral aneurysms and neurosurgeons. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2012;52(12):873–877. doi: 10.2176/nmc.52.873

- Dean MM. End-of-life care for COPD patients. Prim Care Respir J. 2008;17(1):46–50. doi: 10.3132/pcrj.2008.00007

- Gott M, Gardiner C, Small N, Payne S, Seamark D, Barnes S, Halpin D, Ruse C. Barriers to advance care planning in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Palliat Med. 2009;23(7):642–648. doi: 10.1177/0269216309106790

- Janssen DJA, Spruit MA, Schols JMGA, Wouters EFM. A call for high-quality advance care planning in outpatients with severe COPD or chronic heart failure. Chest. 2011;139(5):1081–1088. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-1753

- Wada T, Imai H, Fukutomi E, Chen W-L, Okumiya K, Ishimoto Y, Kimura Y, Sakamoto R, Fujisawa M, Matsubayashi K. Preferred feeding methods for dysphagia due to end-stage dementia in community-dwelling elderly people in Japan. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(9):1810–1811. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13009

- Park SY, Phua J, Nishimura M, Deng Y, Kang Y, Tada K, Koh Y, Asian Collaboration for Medical Ethics (ACME) Study Collaborators and the Asian Critical Care Clinical Trials (ACCCT) Group. End-of-life care in ICUs in East Asia: a comparison among China, Korea, and Japan. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:1114–1124. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003138

- Hoffmann TC, Montori VM, Del Mar C. The connection between evidence-based medicine and shared decision making. JAMA. 2014;312(13):1295–1296. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.10186

- Stacey D, Bennett CL, Barry MJ, Col NF, Eden KB, Holmes-Rovner M, Llewellyn-Thomas H, Lyddiatt A, Légaré F, Thomson R. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Stacey D, ed. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;93(10):CD001431.

- Martinez CH, Richardson CR, Han MK, Cigolle CT. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cognitive impairment, and development of disability: the health and retirement study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(9):1362–1370. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201405-187OC