Abstract

Telephone quitlines are an effective population-based strategy for smoking cessation, particularly among individuals with tobacco-related diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Expanding quitline services to provide COPD-focused self-management interventions is potentially beneficial; however, data are needed to identify specific treatment needs in this population. We conducted a telephone-based survey (N = 5,772) to examine educational needs, behavioral health characteristics, and disease-related interference among individuals with COPD who received services from the American Lung Association (ALA) Lung Helpline. Most participants (73.7%) were interested in COPD-focused information, and few had received prior instruction in breathing exercises (33.9%), energy conservation (26.5%), or airway clearing (32.1%). About one-third of participants engaged in regular exercise, 16.3% followed a special diet, and 81.4% were current smokers. Most participants (78.2%) reported COPD-related interference in daily activities and 30.8% had been hospitalized within the past six months for their breathing. Nearly half of participants (45.4%) reported current symptoms of anxiety or depression. Those with vs. without anxiety/depression had higher rates of COPD-related interference (83.9% vs. 73.5%, p < .001) and past six-month hospitalization (33.4% vs. 28.3%, p < .001). In conclusion, this survey identified strong interest in disease-focused education; a lack of prior instruction in specific self-management strategies for COPD; and behavioral health needs in the areas of exercise, diet, and smoking cessation. Anxiety and depression symptoms were common and associated with greater disease burden, underscoring the importance of addressing coping with negative emotions. Implications for self-management treatments that target multiple behavioral needs of COPD patients are discussed.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a chronic, progressive disease that is projected to be the fourth leading cause of death worldwide by 2030 (Citation1). Most COPD cases are linked to cigarette smoking (Citation2), and the proportion of individuals with COPD who continue to smoke following diagnosis is estimated to be 30–50% (Citation3–6).

Quitting smoking is the most effective and cost-effective therapy for COPD, and the only strategy for slowing progression of lung function decline (Citation2, Citation7). State telephone quitlines represent a promising population-based treatment option for smokers with COPD, as quitlines offer evidence-based tobacco cessation services that are widely accessible and offered at no cost to consumers (Citation8–10). Approximately one-third of quitline callers self-report a chronic disease diagnosis such as COPD (Citation11, Citation12), suggesting good uptake of quitline services among traditionally hard-to-reach groups of smokers.

In addition to smoking cessation, telephone-based treatment programs are well-suited to provide disease-based information to individuals with COPD. Several prior large-scale surveys have identified educational needs among individuals with COPD. Nearly 40% of those with COPD consider themselves “less than adequately” or “poorly informed” about COPD and its treatment (Citation13) and 76% believed there is a strong need for better patient education (Citation14). Individuals with COPD express interest in various topics, including preventing exacerbations, recognizing worsening symptoms, and knowing when emergency help is needed (Citation15, Citation16).

Despite this important gap in information, prior research has shown that providing COPD patients solely with education and action plans is insufficient to reduce hospitalization risk and improve quality of life (Citation17). Instead of education alone, there is a growing emphasis on comprehensive self-management interventions (i.e., structured but personalized and often multi-component interventions, with goals of motivating, engaging, and supporting patients to positively adapt health behaviors and develop skills to better manage their disease) (Citation18). COPD self-management programs are comprised of both patient education and support for behavior change, and typically include components focused on smoking cessation, self-recognition and treatment of exacerbation, exercise/physical activity, nutritional advice, and dyspnea management (Citation19). Further, individuals with COPD also commonly experience mental health symptoms such as depression and anxiety (Citation20), which are associated with greater exacerbation risk (Citation21) and lower health-related quality of life (Citation22). Thus, incorporating counseling on coping with negative emotions may be a useful adjunct to education and behavior change components of self-management. A greater understanding of COPD patients’ needs in the areas of health behavior change and coping with emotional aspects of COPD is critical to guiding patient-centered self-management interventions.

The current study sought to characterize the educational needs as well as behavioral health characteristics, and disease-related interference among individuals with COPD who received services from the American Lung Association (ALA) Lung Helpline and Tobacco Quitline, based in the state of Illinois, USA. Survey items were designed to identify areas of unmet need, to inform future self-management interventions delivered through the nationwide, telephone-based service.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Data for the current study was drawn from the ALA Lung Helpline and Illinois-based Tobacco Quitline survey conducted between 2012 and 2016. Participants (N = 5,772) were initial callers with a self-reported diagnosis of COPD, aged 40–95, who agreed to complete the COPD survey described below. Participants who reported current tobacco use were also asked to complete the tobacco use assessment described below.

Participants were connected to the Helpline through both reactive and proactive means.

The majority of participants (80.2%) were connected to the Helpline through a self-referral (e.g., by calling the toll-free number in response to an advertisement or healthcare provider recommendation). The remainder of participants (19.8%) were connected to the Helpline after answering a call that was placed proactively by Helpline phone counselors. These proactive calls were initiated by a provider referral network system, with most participants referred through a healthcare organization (63.3%) or state agency/non-profit organization (17.1%).

Following completion of the COPD Needs Assessment Survey and the Tobacco Use Assessment, if applicable, options for phone-based counseling were discussed. Tobacco users who indicated current motivation to quit (≥3 on 1–5 scale) were offered free telephone-based counseling through the Illinois Tobacco Quitline if they resided in Illinois, or were directed to their own state tobacco quitline if they resided in another state.

Measures

COPD Needs Assessment Survey

Self-report survey items were administered to assess demographic and clinical characteristics, as well as participants’ health behaviors, mental health, and views on COPD self-management topics. Demographic characteristics included age, sex, race/ethnicity, and level of education. Clinical characteristics included presence of co-occurring medical conditions, whether participants were receiving current medical care (from a general practitioner and/or lung health specialist), past or current participation in a pulmonary rehabilitation program, and current use of a supplemental oxygen device. Health behaviors included whether or not participants engaged in regular exercise, followed a special (i.e., COPD-specific) diet, and currently smoked cigarettes. Participants were also asked if they were experiencing current symptoms of anxiety and/or depression. Participants were asked whether they had received prior instruction in airway clearing, breathing exercises, and energy conservation; whether they would be interested in education about COPD-focused topics; and whether they felt confident in COPD self-management. COPD-related interference was assessed with the following Yes/No items: “Have you been hospitalized in the past six months for your breathing?” and “Does your breathing interfere with activities you like to do?”

Tobacco Use Assessment

Survey items assessed current use of cigarettes and other nicotine/tobacco products and diagnoses of tobacco-related health conditions (i.e., cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, high blood pressure, and/or asthma). Among all current smokers, the two-item Heaviness of Smoking Index (HSI; (Citation23)) was administered to assess nicotine dependence.

Analytic Strategy

We calculated univariate descriptive statistics and frequency distributions for all variables. We next examined demographic, clinical, and smoking-related variables by mental health status (with versus without anxiety/depression), sex (men versus women), and referral source (reactive versus proactive), using t-tests for continuous variables and Pearson chi-square tests for categorical variables. For significant Chi-square tests, we conducted post-hoc Kruskal–Wallis tests to identify significant differences among all pairwise comparisons. Effect sizes were calculated using Cohen’s d values for t-tests, and Cramer’s phi coefficient (φ) values for chi-square tests (Citation24). All tests were two-tailed, and a p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 25.0.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Baseline demographic characteristics of respondents are shown in . Participants were older adults (M = 59.6, SD = 9.3 years), 84.1% were non-Hispanic white, and 66.9% were women. Most participants (73.7%) were interested in receiving COPD-focused information. About two-thirds of participants reported no prior instruction in self-management strategies for COPD such as breathing exercises, energy conservation, or airway clearing. About one-third of participants engaged in regular exercise and 16.3% followed a special diet. Participants reported significant disease burden: 78.2% reported disease-related interference in daily activities and 30.8% had been hospitalized within the past 6 months for their breathing. Nearly three-quarters of participants reported having another chronic illness in addition to their COPD, with the majority reporting more than one comorbid medical condition (50.8%).

Table 1. Sample characteristics, overall and by anxiety/depression status.

Smoking-Related Characteristics

A total of 4,700 participants (81.4%) reported current tobacco use and completed the Tobacco Use Assessment. Of these, the majority were current cigarette smokers (N = 4,649; 98.9%), while 84 participants (1.8%) reported current use of other nicotine/tobacco products (i.e., e-cigarettes, smokeless tobacco, pipes, or cigars). As shown in , current smokers reported moderate to high levels of nicotine dependence, with average HSI score of 3.8 (SD = 1.4). Additionally, 26.2% of smokers (N = 1,216) reported smoking menthol cigarettes. The most commonly reported tobacco-related health conditions were high blood pressure (48.5%), cardiovascular disease (27.6%), and diabetes (22.9%).

Differences by Anxiety/Depression Status

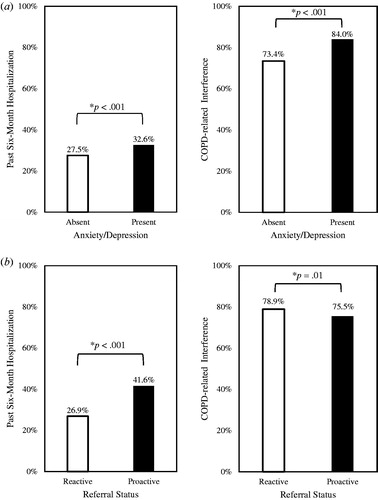

Nearly half of participants (45.4%) reported current symptoms of anxiety or depression. As shown in , those with versus without anxiety/depression were younger, more likely to be female and non-Hispanic white, and less likely to have an education at the high school level. Participants with versus without anxiety/depression reported more medical comorbidities (φ = .13), higher rates of prior instruction in self-management techniques (φ’s .07–.10), and slightly more confidence managing their medical condition (φ = .03). Current anxiety/depression was associated with a small decrease in the rate of regular exercise (φ = .03), and increased likelihood of following a special diet (φ = .03), using supplemental oxygen (φ = .04), and currently smoking (φ = .12). Among smokers, anxiety/depression symptoms were associated with a small effect on greater nicotine dependence severity (d = .16). Anxiety/depression symptoms were also associated with a small effect on increased disease-related interference (φ = .13) and increased past six-month hospitalization (φ = .06; ).

Differences by Sex

As compared to male participants, female participants were more likely to report current anxiety/depression symptoms (51.4% vs. 33.3%), corresponding to a small-to-medium effect size (φ = .17). Women were also more likely to report using supplemental oxygen (26.4% vs. 23.1%; φ = .04), following a special diet (17.2% vs. 14.5%; φ = .03), and currently smoking (82.0% vs. 77.7%; φ = .05), while men were more likely to report regular exercise (38.1% vs. 33.8%; φ = .04).

Differences by Referral Source

Lastly, we examined participant characteristics by Helpline referral source (i.e., reactive vs. proactive). A higher proportion of proactive participants versus self-callers reported their race/ethnicity as African American or Other/Unspecified. There was a small effect of proactive referral source on increased rates of current smoking (89.2% vs. 78.4%; φ = .11). As shown in , proactive referral source was associated with a slightly lower rate of disease-related interference (φ = .03) and a higher rate of past six-month hospitalization (φ = .13).

Discussion

Our population-based needs assessment survey identified strong interest in disease-based education topics among individuals with COPD, and a lack of prior instruction in specific self-management strategies of breathing exercises, energy conservation, and airway clearance. Anxiety and depression were commonly reported comorbidities that were associated with higher likelihood of smoking, and greater impairment and hospitalization risk. Consistent with prior research, anxiety and depression symptoms were more common among women than men. We also identified differences in participant characteristics by recruitment source, suggesting that proactive means of referral may be more likely to reach current smokers and those at a higher level of COPD severity. Although effect sizes were generally in a small range, findings are expected to be clinically significant when viewed through the lens of population-level trends for individuals with COPD.

The proportion of current smokers was higher in our survey than in the general population of those with COPD (Citation3–6), likely due to callers who were seeking information on quitting smoking or were referred by healthcare providers for smoking cessation services. Among current smokers, we observed high rates of nicotine dependence, with nearly 65% smoking their first cigarette within 5 minutes of waking. Tobacco cessation, inclusive of both behavioral support and pharmacotherapy, should remain a foremost clinical priority of self-management interventions in COPD (Citation2). Although limited information is available regarding how best to tailor smoking cessation interventions for those with COPD, a recent meta-analysis supported the effectiveness of four specific behavior change techniques: facilitating action planning, prompting self-recording, advising on methods of weight control, and advising on use of social support (Citation25). Additionally, the COPD-specific behavior change technique of linking COPD and smoking (i.e., drawing an explicit link between cessation and slowing lung function decline) was shown to be effective in this population.

Nearly half of participants endorsed current symptoms of depression or anxiety, consistent with many prior studies that document elevated rates of these mental health symptoms among individuals with COPD (Citation21). Importantly, these symptoms were associated with higher disease burden and recent history of COPD-related hospitalization. Depression and anxiety symptoms may be related to long-standing individual difference characteristics, such as anxiety sensitivity (Citation26) or emotional intelligence (Citation27), which interact with the stress of COPD progression to produce emotional distress. Self-management interventions should address emotional aspects of adjustment to COPD, such as patients’ fears associated with the uncertainty, progression, and suffering of their disease (Citation28). These interventions may be particularly applicable to women with COPD, who experience higher rates of psychiatric comorbidity and poorer symptom-related quality of life (Citation29).

We found that participants who endorsed current symptoms of anxiety or depression were more likely to report a history of self-management instruction in COPD topics (i.e., breathing activities, energy conservation, and airway clearance). It may be that those with elevated health-related anxiety were more likely to seek out or attend to this instruction from healthcare providers. Further, only about one-third of participants reported engaging in regular exercise, and this rate was lower among those with current symptoms of anxiety and depression. Future research should further characterize engagement in physical activity in relation to mental health functioning, using measures appropriate for those with COPD (Citation30). As physical activity has numerous benefits to COPD patients, including reduced risk of exacerbations (Citation31), this represents another important target for self-management interventions.

We identified important differences in participants by referral status. Proactively referred participants were more likely than self-callers to have a history of hospitalization for breathing condition within the past six months. Past hospitalization is a key predictor of future exacerbation risk (Citation32), making this a priority group to target in reducing healthcare burden associated with COPD. Further, a proactive mode of entry may facilitate successful smoking cessation (Citation33), particularly among those with chronic lung disease (Citation34). Development of future telephone-based interventions may benefit from using proactive means of recruitment (i.e., through physician fax or electronic medical record referral) to maximize health benefits.

Our findings provide important clinical implications for the development and refinement of self-management programs for COPD. Initial findings have shown self-management programs (e.g., health coaching) have potential to decrease COPD-related hospitalizations and increase quality of life (Citation35). Our study would suggest potential utility of integrating intervention components such as intensive smoking cessation counseling (Citation8), cognitive behavioral therapy for mood management (Citation36), and exercise training (Citation37). Novel experimental approaches could help to optimize the effectiveness of multi-component interventions on clinical outcomes of interest (i.e., COPD exacerbations and quality of life) (Citation38) and develop adaptive, individualized treatment programs (Citation39). Treatment delivery format is also an important consideration in intervention scalability and impact within this population. Phone-based treatment, such as that offered by the ALA Helpline, is a highly acceptable and feasible option. Computer and mobile technology platforms are also increasingly well-positioned to deliver scalable and effective self-management interventions for COPD (Citation40).

Several methodological considerations warrant comment. First, COPD diagnoses were based on participant self-report and did not incorporate clinical or spirometric verification, so we are unable to assess for diagnostic accuracy. Second, survey responses were provided by telephone, which precluded our ability to administer full-length questionnaire assessments of constructs such as disease impairment and emotional functioning. As COPD is a heterogeneous condition, not all patients will have the self-management treatment needs (Citation41), and future research should examine treatment needs as a function of individual patient profiles (i.e., disease phenotype and symptom severity). Lastly, the needs assessment survey was cross-sectional, so we are unable to assess changes in variables over time, or response to targeted treatment.

In summary, we identified strong interest in disease-focused education; a lack of prior instruction in specific self-management strategies for COPD; and behavioral health needs in the areas of exercise, diet, and smoking cessation among individuals with COPD. Anxiety and depression were commonly reported comorbidities that were associated with greater impairment and hospitalization risk. Self-management interventions that target multiple behavioral and emotional needs of COPD patients are needed. As tobacco quitlines commonly reach those with chronic disease diagnoses such as COPD (Citation11, Citation12), they represent a logical mode of delivery for telephone-based COPD self-management interventions.

Disclosure Statement

Dr. Kalhan reports grants and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, grants from PneumRx (BTG), grants from Spiration, grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, personal fees from CVS Caremark, personal fees from Aptus Health, grants and personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline, and personal fees from Boston Scientific, which were outside the submitted work. Authors report no other conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Cruz AA. Global surveillance, prevention and control of chronic respiratory diseases: a comprehensive approach. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007.

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: 2018 Report. 2018.

- Schauer GL, Wheaton AG, Malarcher AM, Croft JB. Smoking prevalence and cessation characteristics among U.S. adults with and without COPD: findings from the 2011 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. COPD. 2014;11(6):697–704. doi:10.3109/15412555.2014.898049.

- Vozoris NT, Stanbrook MB. Smoking prevalence, behaviours, and cessation among individuals with COPD or asthma. Respir Med. 2011;105(3):477–484. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2010.08.011.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease among adults: United States, 2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR); 2012.

- Ford ES, Croft JB, Mannino DM, Wheaton AG, Zhang X, Giles WH. COPD surveillance: United States, 1999–2011. Chest. 2013;144(1):284–305. doi:10.1378/chest.13-0809.

- Godtfredsen NS, Lam TH, Hansel TT, Leon ME, Gray N, Dresler C, Burns DM, Prescott, E, Vestbo J. COPD-related morbidity and mortality after smoking cessation: status of the evidence. Eur Respir J. 2008;32(4):844–853. doi:10.1183/09031936.00160007.

- Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, Bailey WC, Benowitz NL, Curry SE, Dorfman SF, Froelicher ES, Goldstein MG, Healton CG et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2008.

- Sheffer C, Stitzer M, Landes R, Brackman SL, Munn T. In-person and telephone treatment of tobacco dependence: a comparison of treatment outcomes and participant characteristics. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(8):e74–e82. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.301144.

- Maher JE, Rohde K, Dent CW, Stark MJ, Pizacani B, Boysun MJ, Dilley JA, Yepassis-Zembrou PL. Is a statewide tobacco quitline an appropriate service for specific populations? Tob Control. 2007;16 Suppl 1:i65–i70. doi:10.1136/tc.2006.019786.

- Bush T, Zbikowski SM, Mahoney L, Deprey M, Mowery P, Cerutti B. State quitlines and cessation patterns among adults with selected chronic diseases in 15 States, 2005–2008. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E163. doi:10.5888/pcd9.120105.

- Nair US, Bell ML, Yuan NP, Wertheim BC, Thomson CA. Associations between comorbid health conditions and quit outcomes among smokers enrolled in a state quitline, Arizona, 2011–2016. Public Health Rep. 2018;133(2):200–206. doi:10.1177/0033354918764903.

- Barr RG, Celli BR, Martinez FJ, Ries AL, Rennard SI, Reilly Jr JJ, Sciurba FC, Thomashow BM, Wise RA. Physician and patient perceptions in COPD: the COPD Resource Network needs assessment survey. Am J Med. 2005;118(12):1415–e9. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.07.059.

- Confronting COPD in America: Executive Summary. New York, NY: Schulman, Ronca, and Bucuvalas Inc; 2001:1–20.

- Carlson ML, Ivnik MA, Dierkhising RA, O'byrne MM, Vickers KS. A learning needs assessment of patients with COPD. Medsurg Nurs. 2006;15(4):204–212.

- Barnes N, Calverley PM, Kaplan A, Rabe KF. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and exacerbations: patient insights from the global hidden depths of COPD survey. BMC Pulm Med. 2013;13:54. doi:10.1186/1471-2466-13-54.

- Fan VS, Gaziano JM, Lew R, Bourbeau J, Adams SG, Leatherman S, Thwin SS, Huang GD, Robbins R, Sriam PS, et al. A comprehensive care management program to prevent chronic obstructive pulmonary disease hospitalizations: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(10):673–683. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-156-10-201205150-00003.

- Effing TW, Vercoulen JH, Bourbeau J, Trappenburg J, Lenferink A, Cafarella P, Coultas, D, Meek, P, van der Valk, P, Bischoff, EWMA, et al. Definition of a COPD self-management intervention: International Expert Group consensus. Eur Respir J. 2016;48(1):46–54. doi:10.1183/13993003.00025-2016.

- Effing TW, Bourbeau J, Vercoulen J, Apter AJ, Coultas D, Meek P, Valk PV, Partridge MR, Palen JV. Self-management programmes for COPD: moving forward. Chron Respir Dis. 2012;9(1):27–35. doi:10.1177/1479972311433574.

- Panagioti M, Scott C, Blakemore A, Coventry PA. Overview of the prevalence, impact, and management of depression and anxiety in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:1289–1306.

- Atlantis E, Fahey P, Cochrane B, Smith S. Bidirectional associations between clinically relevant depression or anxiety and COPD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2013;144(3):766–777. doi:10.1378/chest.12-1911.

- Blakemore A, Dickens C, Guthrie E, Bower P, Kontopantelis E, Afzal C, Coventry PA. Depression and anxiety predict health-related quality of life in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:501–512. doi:10.2147/COPD.S58136.

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Rickert W, Robinson J. Measuring the heaviness of smoking: using self‐reported time to the first cigarette of the day and number of cigarettes smoked per day. Br J Addict. 1989;84(7):791–800. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb03059.x.

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988.

- Bartlett YK, Sheeran P, Hawley MS. Effective behaviour change techniques in smoking cessation interventions for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a meta‐analysis. Br J Health Psychol. 2014;19(1):181–203. doi:10.1111/bjhp.12071.

- Mathew AR, Yount SE, Kalhan R, Hitsman B. Psychological functioning in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a preliminary study of relations with smoking status and disease impact. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018. doi:10.1093/ntr/nty102.

- Benzo RP, Kirsch JL, Dulohery MM, Abascal-Bolado B. Emotional intelligence: a novel outcome associated with wellbeing and self-management in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(1):10–16. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201508-490OC.

- Wortz K, Cade A, Menard JR, Lurie S, Lykens K, Bae S, Jackson B, Su F, Singh K, Coultas D. A qualitative study of patients' goals and expectations for self-management of COPD. Prim Care Respir J. 2012;21(4):384–391. doi:10.4104/pcrj.2012.00070.

- Raghavan D, Varkey A, Bartter T. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the impact of gender. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2017;23(2):117–123. doi:10.1097/MCP.0000000000000353.

- Mussa CC, Tonyan L, Chen YF, Vines D. Perceived satisfaction with long-term oxygen delivery devices affects perceived mobility and quality of life of oxygen-dependent individuals with COPD. Respir Care. 2018;63(1):11–19. doi:10.4187/respcare.05487.

- Garcia-Aymerich J, Lange P, Benet M, Schnohr P, Antó JM. Regular physical activity reduces hospital admission and mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a population based cohort study. Thorax. 2006;61(9):772–778. doi:10.1136/thx.2006.060145.

- Müllerova H, Maselli DJ, Locantore N, Vestbo J, Hurst JR, Wedzicha JA, Bakke P, Agusti A, Anzueto A. Hospitalized exacerbations of COPD: risk factors and outcomes in the ECLIPSE cohort. Chest. 2015;147(4):999–1007. doi:10.1378/chest.14-0655.

- Guy MC, Seltzer RG, Cameron M, Pugmire J, Michael S, Leischow SJ. Relationship between smokers' modes of entry into quitlines and treatment outcomes. Am J Health Behav. 2012;36(1):3–11. doi:10.5993/AJHB.36.1.1.

- Melzer AC, Clothier BA, Japuntich SJ, Noorbaloochi S, Hammett P, Burgess DJ, Joseph AM, Fu SS. Comparative effectiveness of proactive tobacco treatment among smokers with and without chronic lower respiratory disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15(3):341–347. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201707-582OC.

- Benzo R, Vickers K, Novotny PJ, Tucker S, Hoult J, Neuenfeldt P, Connett J, Lorig K, McEvoy C. Health coaching and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease rehospitalization: a randomized study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194(6):672–680. doi:10.1164/rccm.201512-2503OC.

- Livermore N, Dimitri A, Sharpe L, McKenzie DK, Gandevia SC, Butler JE. Cognitive behaviour therapy reduces dyspnoea ratings in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2015;216:35–42. doi:10.1016/j.resp.2015.05.013.

- Varas AB, Cordoba S, Rodriguez-Andonaegui I, Rueda MR, Garcia-Juez S, Vilaro J. Effectiveness of a community-based exercise training programme to increase physical activity level in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized controlled trial. Physiother Res Int. 2018;23(4):e1740. doi:10.1002/pri.1740.

- Collins LM. Optimization of behavioral, biobehavioral, and biomedical interventions: The Multiphase Optimization Strategy (MOST). New York: Springer; 2018.

- Lei H, Nahum-Shani I, Lynch K, Oslin D, Murphy SA. A “SMART” design for building individualized treatment sequences. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2012;8:21–48. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143152.

- McCabe C, McCann M, Brady AM. Computer and mobile technology interventions for self-management in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;5:CD011425. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011425.pub2.

- Trappenburg J, Jonkman N, Jaarsma T, van Os-Medendorp H, Kort H, de Wit N, Hoes A, Schuurmans M. Self-management: one size does not fit all. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;92(1):134–137. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2013.02.009.