Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the underdiagnosis of COPD and its determinants based on the Tunisian Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease study. We collected information on respiratory history symptoms and risk factors for COPD. Post-bronchodilator (Post-BD) FEV1/FVC < the lower limit of normal (LLN) was used to define COPD. Undiagnosed COPD was considered when participants had post-BD FEV1/FVC < LLN but were not given a diagnosis of emphysema, chronic bronchitis or COPD. 730 adults aged ⩾40 years selected from the general population were interviewed, 661 completed spirometry, 35 (5.3%) had COPD and 28 (80%) were undiagnosed with the highest prevalence in women (100%). When compared with patients with an established COPD diagnosis, undiagnosed subjects had a lower education level, milder airway obstruction (Post-BD FEV1 z-score −2.2 vs. −3.7, p < 0.001), fewer occurrence of wheezing (42.9% vs. 100%, p = 0.009), less previous lung function test (3.6% vs. 42.8%, p = 0.019) and less visits to the physician (32.1% vs. 85.7%, p = 0.020) in the past year. Multivaried analysis showed that the probability of COPD underdiagnosis was higher in subjects who had mild to moderate COPD and in those who did not visit a clinician and did not perform a spirometry in the last year. Collectively, our results highlight the need to improve the diagnosis of COPD in Tunisia. Wider use of spirometry should reduce the incidence of undiagnosed COPD. Spirometry should also predominately be performed not only in elderly male smokers but also in younger women in whom the prevalence of underdiagnosis is the highest.

Keywords:

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) ranks within the top three causes of mortality in the global burden of disease [Citation1,Citation2] with an estimated 328,615,000 people (168 million men and 160 million women) with this condition [Citation3,Citation4]. Exacerbations of COPD are the most common causes of repeated hospital admissions and their financial cost is substantial [Citation1,Citation2]. Nonetheless, several studies showed that a high proportion of individuals fulfilling COPD diagnosis criteria remain undiagnosed or are only identified during an exacerbation or after significant loss of lung function [Citation5,Citation6].

The prevalence of undiagnosed COPD among people with smoking history varies worldwide [Citation7] and ranges from 10.1% in the UK [Citation8], 13.1% in Japan [Citation9] and reaches 34.8% in Denmark [Citation10]. Moreover, data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Study (NHANES III) suggest that over 63% of adults with impaired lung function have never been diagnosed with a lung disease [Citation11].

The Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease (BOLD) study carried out in Tunisia showed that 5.3% of the residents of Sousse, 40 years of age or over, had at least Stage I COPD [Citation12]. These results suggest that the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease that physicians see in their clinical practices may be the tip of the iceberg.

The reasons for COPD to be undiagnosed are likely multifactorial and understanding them is critical. Indeed, COPD can be asymptomatic in its early stages and people who seem to have good self-reported health status and lower comorbidity burden might be overlooked even when they have been exposed to risk factors (e.g. smoking) for COPD.

These signs represent missed opportunities to decrease disease burden through early intervention strategies such as optimal management, smoking cessation support and medications prescriptions [Citation13,Citation14].

In developing countries, and especially in Tunisia, studies of undiagnosed COPD in a large sample of adults are rare. This is probably due to the difficulty to undertake population-based samples to identify subjects without a previous diagnosis of obstructive lung disease. However, such studies are important since undiagnosed COPD has been associated with increased health care cost and accruing more cardiovascular risk factors [Citation15]. Understanding factors that contribute to COPD underdiagnosis lead to early intervention strategies that radically improve future prospects for the patients [Citation16].

In the current study, we used data from the Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease (BOLD) study conducted in Sousse (Tunisia) to determine the prevalence and the factors associated with undiagnosed COPD among adults aged ⩾40 years.

Materials and methods

We followed the BOLD protocol as it has been described elsewhere [Citation12,Citation17,Citation18]. The ethics committee of the medical school of Sousse approved the study protocol and all the participants agreed by signing the informed written consent.

Study population

The survey was conducted on a sex-stratified representative random sample of 807 subjects, aged ≥40, selected from the general population and living in the urban area of Sousse (Tunisia). Out of 730 eligible participants, 717 were eligible for spirometry and 661 completed the full protocol, including pre- and post-BD spirometry, and met the quality control criteria. Exclusion criteria were mental illness, institutionalization, inability to conduct spirometry, and contraindications to salbutamol.

Lung function

Spirometry was conducted according to ATS criteria [Citation19] by trained and certified technicians using an EasyOne spirometer (ndd Medizintechnik AG, Zurich, Switzerland). Measurements were made before and 15 min after administering 200 μg of Salbutamol (Ventolin; GlaxoSmithKline, Middlesex, UK). Spirometry data were submitted electronically to the Pulmonary Function Quality Control Center in London, UK, where each spirometry was reviewed and only spirograms that met acceptability and reproducibility criteria were included.

Study questionnaire

The questionnaires used during the BOLD study were administered by trained and certified interviewers in the participants’ native language. To ensure accuracy, all the questions were translated from English into Arabic and then back-translated to ensure validity.

The questionnaire asked about sociodemographic characteristics, smoking status, respiratory diagnoses, disease symptoms, comorbidities, activity limitation and risk factors for COPD. In addition, subjects were asked if, in the past 12 months, they ever had a period when they had breathing problems that got so bad that they need to see a doctor or other health care provider. We also obtained information about the number of hospitalizations in association with their breathing problems over the previous 12 months.

Subjects were also asked about any pharmacological respiratory treatments they were taking on a regular basis and those that they take only for the relief of symptoms.

Finally, to assess long-term occupational exposure to airway irritants, participants were asked whether they had worked for at least 3 months in jobs where they could be exposed to one of the following: (1) organic dust; (2) inorganic dust and (3) irritant gases, fumes or vapors.

Definitions

Airways obstruction was defined as a post-bronchodilator (post-BD) FEV1/FVC below the lower limit of normal (LLN) using prediction equations from the Global Lung Function Initiative (GLI) [Citation20], through the GLI-2012 Desktop Software for Large Data Sets (published on www.lungfunction.org).

The diagnosis of COPD was considered in any patient who has a post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC < LLN accompanied by symptoms of cough, sputum production, or dyspnea.

COPD stages of severity were categorized using the proposed classification based on z-score of post-bronchodilator FEV1 [Citation21]: mild (z-score, ≥ −2), moderate (-3 ≤ z-score < −2), severe (-4 ≤ z-score < −3) and very severe (z-score < −4).

Doctor diagnosed COPD was defined as a self-reported physician’s diagnosis of chronic bronchitis, emphysema, or COPD based on an affirmative response to the question: “Has a doctor or other health-care provider ever told you that you have/had …?”). The reported diagnosis of COPD was considered correct if a post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC < LLN was accompanied by symptoms of cough, sputum production, or dyspnea at the time of the study visit.

Undiagnosed COPD was considered when participants had a post-BD FEV1/FVC < LLN and symptoms of cough, sputum production, or dyspnea but were not given a medical diagnosis of chronic bronchitis, emphysema or COPD

Prior lung function test was also recorded “Has a doctor or other health-care provider ever had you blow into a machine or device to measure your lungs function?” as well as spirometry during the past 12 months “Have you used such a machine during the past 12 months?”.

Nonsmokers referred to subjects who had smoked on average <1 cigarette/day for <1 year or had never smoked and ever smokers (current or former smokers) were defined as persons who had smoked > 20 packs of cigarettes in a lifetime or > 1 cigarette/day for a year.

Severity of self-reported dyspnea was recorded according to the modified Medical Research Council dyspnea scale (0-4), with dyspnea defined as present with a score ≥ 1.

Presence of self-reported cough was assessed using the following question: “Do you usually cough when you don’t have a cold?” and self-reported phlegm was assessed using the following question: “Do you usually bring up phlegm from your chest, or do you usually have phlegm in your chest that is difficult to bring up when you don’t have a cold?”

Statistical analysis

BOLD participants who completed the study questionnaires and had acceptable post-BD spirometry measures were included in the present analysis.

All statistical tests were performed with IBM SPSS statistics software (version 23). Continuous measures were tested for normality using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Normally distributed data were expressed as mean and standard deviation and were compared using an unpaired t-test and not-normally distributed data were expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR) and compared using Mann-Whitney U-test. Chi squared or Fisher exact test were used to compare qualitative variables.

The association of health status and sociodemographic parameters with diagnosis of obstructive pulmonary disease was assessed using univariable and multivariable logistic regressions. P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Sample demographics

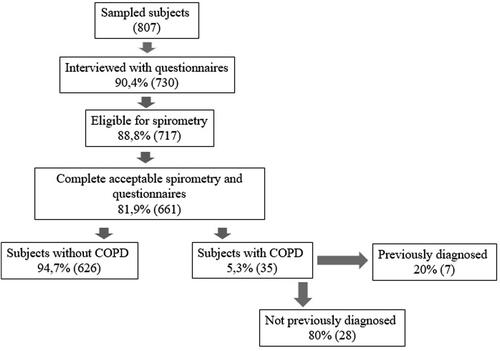

Detailed description of participation rates is presented in . Of the 807 subjects sampled from Sousse region in Tunisia, 717 were interviewed. The response rate was 90%. The number of non-responders and ineligible participants were 77 and 13, respectively. The reasons for non-response included refusals, contact failures, spirometry ineligibility, and failed attempts.

Figure 1. Identification of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease subjects with and without a previous diagnosis of COPD.

Among the 717 interviewees, 56 failed to complete the spirometry testing and 661 completed acceptable and reproducible post-BD spirometry and questionnaires and were included in this analysis ().

There were no significant differences in age, sex and smoking status between responders and non-responders, thus, the pattern of these variables distribution was similar in the two groups, suggesting that the study participants are highly representative of the general population

Current and former smoking were more prevalent in men than in women (48.5% vs. 7.4% and 26.2% vs. 1.7%, respectively). 60% of the participants were never smokers and 41% were actively employed.

Detailed information on socio-demographics and smoking status of the studied population are presented in .

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of the study population.

Prevalence and characteristics of COPD

The overall prevalence of COPD using LLN criteria for FEV1/FVC, was 5.3% (35/661) Of those who had spirometry-confirmed COPD, male sex had substantially greater representation than female sex (82.9% vs. 17.1%, respectively; p < 0.001), including across each age group. Description of the subjects’ socio-demographic characteristics is shown in .

Prevalence and characteristics of undiagnosed COPD

Of the subjects who fulfilled the spirometric criteria of COPD, only 20% (7/35) reported a prior physician-diagnosis (). Conversely, of the seven subjects with physician-diagnosed COPD, all had spirometry confirmed COPD.

In the present study, 100% of the women with COPD were undiagnosed; however, the difference between women and men in the proportion of underdiagnosis was not statistically significant (). Analysis of the continuous variable age did not reveal significant differences between the diagnosed and the undiagnosed COPD subjects (). When 10-year age categories were considered, the 50- to 59-year age group had the highest rate of COPD underdiagnosis (46.4%). According to the World Health Organization body mass index cutoff level, 35.7% (10/28) of the undiagnosed COPD subjects were either obese or overweight; however, BMI did not significantly differ between the two groups of subjects.

Table 2. Sociodemographic characteristics of subjects with and without previous diagnosis of COPD.

COPD underdiagnosis was higher among those patients that had a lower education level (p = 0.025); indeed, 50% (14/28) of the participants without a previous diagnosis of COPD were illiterate or only attended primary school ().

25% (7/28) of the undiagnosed COPD subjects were unemployed and approximately 53% (15/28) of them were current smokers (92.9% of the men vs. 7.1% of the women) with all being cigarette smokers except for 2 water pipe smokers, 2 pipe smokers and 2 cigar smokers. The mean number of years since first smoking was 40 (SD = 12) and the mean pack-year was 46 (SD = 34).

showed the clinical characteristics of the study population. Among undiagnosed participants, 17.9% (5/28) had severe airway obstruction and none had the very severe form of the disease, compared with 85.7 (6/7) and 14.3% (1/7) of the subjects with a previous diagnosis, respectively (p < 0.001). There was a clear correlation between COPD underdiagnosis and the disease severity, with diagnosis being missed significantly more often in mild compared to more severe disease (OR 0.7, 95% CI 0.4 − 0.9, p < 0.001).

Table 3. Clinical characteristics of the study population.

Regarding the respiratory symptoms, the group with a previous diagnosis of COPD reported greater occurrence of wheezing (p = 0.009) but did not differ from the other group regarding the prevalence of self-reported chronic cough, chronic phlegm and dyspnea.

Simple logistic regression analysis showed that the presence of self-reported respiratory symptom wheezing increased the likelihood of having a physician diagnosis of COPD (OR 0.4, 95% CI 0.1 − 0.6, p = 0.006).

No difference was observed between the groups in the prevalence of self-reported non-respiratory co-morbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, depression and heart disease ().

Among all the participants with COPD, 40% (14/35) reported a previous lung function test ever and having done a spirometry test in the past 12 months was a significant predictor for COPD being diagnosed by a physician (OR 0.6, 95% CI 0.2 − 1.0, p = 0.003).

68% (19/28) of the subjects without a previous diagnosis of COPD did not visit a physician in the past 12 months and the crude odds of COPD underdiagnosis was significantly higher among those individuals (OR 0.3, 95% CI 0.1 − 0.6, p = 0.009).

However, age, sex, BMI, schooling, economic classification, occupation, biomass exposure, smoking status and having one or more comorbidity did not demonstrate a significant association with the underdiagnosis of COPD.

The adjusted odds of COPD underdiagnosis were significantly higher in those subjects who had mild to moderate COPD and in those who did not visit a clinician and did not perform a spirometry test in the past year.

Discussion

The most important findings of this study of COPD underdiagnosis in Sousse, Tunisia were first, 80% (28/35) of men and women aged ≥ 40 years with COPD according to LLN criteria did not report a prior physician diagnosis of COPD; second, the main determinants for COPD underdiagnosis were milder airway obstruction (mild to moderate COPD), lower occurrence of wheezing and a lack of previous spirometry; third, having visited the doctor and performed a spirometry in the past 12 months decreased COPD underdiagnosis.

Our findings confirm the substantial frequency of undiagnosed obstructive lung diseases seen in studies derived from other national representative samples (e.g. 80.8% in Colombia [Citation22], 85.9% in Austria [Citation23] and 70% in Canada [Citation24]).

The substantial differences observed between diagnosed and undiagnosed subjects deserve special consideration.

In comparison to the diagnosed subjects, participants with undiagnosed COPD exhibited milder airflow obstruction, less frequency of wheezing, lower level of education, less visits to the physician and lack of previous spirometry. These findings confirm several previous population-based studies [Citation25,Citation26] with similar results.

In our cohort, 82.1% (23/28) of the undiagnosed COPD subjects were classified as suffering from mild or moderate COPD whereas 100% (7/7) of the subjects with diagnosed COPD had severe or very severe COPD. Moreover, mean post-bronchodilator FEV1 and FVC and median FEV1/FVC z-scores were respectively, 40, 54 and 48% higher in undiagnosed compared to diagnosed subjects. Our findings also showed that mild and moderate COPD were significantly associated with the risk of being undiagnosed in both the unadjusted and adjusted analyses suggesting that the disease is diagnosed in its more advanced phase. In line with our findings, Kate et al. [Citation26] showed in a systematic review and meta-analysis that individuals with mild COPD were less likely to receive a diagnosis than those with more severe disease.

Among respiratory symptoms, lower occurrence of wheezing was significantly associated with the underdiagnosis of COPD in the unadjusted analysis whereas chronic cough and chronic phlegm were not associated with a previous diagnosis of COPD in any of the pooled analysis. A possible explanation of this finding could be that wheezing is the most objective symptom of COPD and can be easily perceived by third parties whereas chronic cough and chronic phlegm are considered habitual, chronically accepted and typical of persons who smoke. Thus, the onset of wheezing induces more frequently patients to seek medical care. In addition, according to the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease [Citation27], doctors are more likely to test for COPD in patients with a higher burden of wheezing.

Our results also showed that 25% (7/28) of the subjects with undiagnosed COPD have ever performed a previous spirometry but only one of them (3.6% 1/28) performed a spirometry in the past 12 months vs. 42.8% (3/7) of the diagnosed subjects (p = 0.019). Our findings sustain the results of Herrera et al. [Citation28] showing that the fact of not performing a spirometry during the last year increases the risk of being undiagnosed with COPD.

The present study also showed that two thirds of the undiagnosed participants did not visit any physician in the past 12 months and that those subjects, have significantly more risk of COPD underdiagnosis. Primary care physicians have a vital role to play in the diagnosis of COPD, where earlier diagnosis might reduce morbidity and prevent or delay hospital admission, reducing then financial costs associated with the management of COPD [Citation29]. Effective early diagnosis requires both patient education in order to encourage earlier presentation and case-finding using spirometry in the symptomatic patients and possibly screening of at-risk subjects [Citation30,Citation31].

It is also important to mention that we observed a high rate of COPD underdiagnosis in women who participated in the study. Indeed, 100% (6/6) of the women with COPD were undiagnosed. This finding supports several previous population-based studies with similar observations [Citation28,Citation32,Citation33]. The epidemiology of COPD in Tunisia still indicates that men are six times more likely to have COPD than women [Citation12]. These results could be due to differences in the use of cigarettes. Indeed, in Tunisia, women rarely smoked cigarettes (3.9%), while 70.5% of the men smoked [Citation12] and consequently, physicians might be less likely to consider COPD when confronted by a female patient with respiratory symptoms [Citation34].

Concerning the association between smoking and COPD underdiagnosis, our results are consistent with those of the PUMA study [Citation28] and those of Kate et al., [Citation26] showing that underdiagnosis is as common in individuals with COPD who never smoked as in ever smokers. However, according to Shin et al. [Citation35] smoking represents a meaningful and significant correlate of undiagnosed COPD.

In the present study, over 85% (6/7) of the subjects with previously diagnosed COPD were given a smoking cessation advice. Nonetheless, over half of them were still smokers. In line with the findings of Stead et al. [Citation36], physician advice alone seems to have a small effect on quit rate; indeed, it should be given at every opportunity with the offer of further support and drug therapy.

Co-morbidities not related to the respiratory system, such as heart disease or hypertension, had no effect on COPD diagnosis, a finding in line with the results of the meta-analysis of Halbert et al. [Citation37]. A likely explanation is that the presence of respiratory disease increases the likelihood of being seen by a respiratory physician, who then performs spirometry and diagnoses COPD. However, the presence of cardiovascular comorbidities does not appear to alert health care providers to consider a diagnosis of COPD, which suggests a significant opportunity for education.

The present study has the strength of being based on a large nationally representative sample of subjects. To our knowledge, it is the first and largest assessment of COPD using spirometry in Tunisia. Both spirometry and questionnaires were conducted with a high-quality control from the BOLD center of operations, and only spirometry and bronchodilator tests that met high-quality scores were used for the final analysis, which likely reduces bias due to methodological issues.

In the current study, we used the LLN criterion instead of the fixed FEV1/FVC ratio < 0.70 (FR) in the evaluation of airway obstruction since it is well recognized that using a fixed ratio will not only over-diagnose airflow obstruction in the older population but also miss the diagnosis in younger subjects [Citation38]. Using LLN instead of the FR dropped the numbers diagnosed from 51 to 35 subjects, meaning the fixed ratio over diagnosed the condition by 46%. Moreover, we noticed that subjects diagnosed with COPD by the FR, were older and had less cough, sputum and wheeze and had significantly higher FEV1/FVC z-scores than those classified as having COPD by LLN. Thus, use of the FR for defining airflow obstruction may lead to the inclusion of a significant number of older people with breathlessness as having COPD, who may, in fact, have age-related changes in lung function as the cause for their symptoms.

However, some limitations have to be noted: First, the term “COPD” is not recognized equally among Tunisian participants and awareness of the disease varies. Second, our analyses, based on self-reported diagnosis of COPD, present a risk of misclassification, indeed, reported ‘doctor-diagnosed’ COPD was ascertained only by questionnaire and might have been subject to selective recall. Third, an oversight might have been present when asking for a prior lung function test and we cannot be sure if the reported prior lung function tests included post-BD measurements.

Conclusions

Collectively, our results showed that COPD underdiagnosis is a major health problem in Tunisia and highlight the need to improve the diagnosis of the disease. Wider use of spirometry should reduce the incidence of undiagnosed COPD. Spirometry should also predominately be performed not only in elderly male smokers but also in younger women in whom the prevalence of underdiagnosis is the highest.

Acknowledgements

The present authors would like to thank the BOLD coordinating center: for providing technical training, questionnaires and assistance. All investigators and local administrators are also acknowledged for their great assistance in field surveying during the current study.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Murray CJL , Lopez AD . Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990–2020: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 1997;349(9064):1498–1504. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07492-2

- Murray CJ , Lopez AD . Measuring the global burden of disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(5):448–457. DOI:10.1056/NEJMra1201534

- Santo SR , Lizzi ES , Vianna EO . Characteristics of undiagnosed COPD in a senior community center. Int J COPD. 2014;9:1155–1161.

- Han MK , Steenrod AW , Bacci ED , et al. Identifying Patients with undiagnosed COPD in primary care settings: Insight from screening tools and epidemiologic studies. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2015;2(2):103–121. DOI:10.15326/jcopdf.2.2.2014.0152

- Roche N , Gaillat J , Garre M , et al. Acute respiratory illness as a trigger for detecting chronic bronchitis in adults at risk of COPD: a primary care survey. Prim Care Respir J. 2010;19(4):371–377. DOI:10.4104/pcrj.2010.00042

- Fu SN , Yu WC , Wong CKH , et al. Prevalence of undiagnosed airflow obstruction among people with a history of smoking in a primary care setting. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:2391–2399. DOI:10.2147/COPD.S106306

- Coultas DB , Mapel DW . Undiagnosed airflow obstruction: prevalence and implications. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2003;9(2):96–103. DOI:10.1097/00063198-200303000-00002

- Al Omari M , Khassawneh BY , Khader Y , et al. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among adult male cigarettes smokers: a community-based study in Jordan. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:753–758.

- Sekine Y , Yanagibori R , Suzuki K , et al. Surveillance of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in high-risk individuals by using regional lung cancer mass screening. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:647–656. DOI:10.2147/COPD.S62053

- Ulrik CS , Lokke A , Dahl R , et al. Early detection of COPD in general practice. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2011;6:123–127.

- Mannino DM , Gagnon RC , Petty TL , et al. Obstructive lung disease and low lung function in adults in the United States: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(11):1683–1689. DOI:10.1001/archinte.160.11.1683

- Daldoul H , Denguezli M , Jithoo A , et al. Prevalence of COPD and tobacco smoking in Tunisia – results from the BOLD Study. IJERPH. 2013;10(12):7257–7271. DOI:10.3390/ijerph10127257

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and World Health Organization . Global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease: Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA. Available from: http://www.goldcopd.com.

- Soriano JB , Zielinski J , Price D . Screening for and early detection of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2009;374(9691):721–732. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61290-3

- Siersted HC , Boldsen J , Hansen HS , et al. Population based study of risk factors for underdiagnosis of asthma in adolescence: odense schoolchild study. BMJ. 1998;316(7132):651–655.

- Anthonisen NR , Connett JE , Kiley JP , et al. Effects of smoking intervention and the use of an inhaled anticholinergic bronchodilator on the rate of decline of FEV1. The lung health study. JAMA. 1994;272(19):1497–1505. DOI:10.1001/jama.1994.03520190043033

- Buist AS , Vollmer WM , Sullivan SD , et al. The burden of obstructive lung disease initiative (BOLD): rationale and design. COPD. 2005;2(2):277–283. DOI:10.1081/COPD-57610

- Buist AS , McBurnie MA , Vollmer WM , BOLD Collaborative Research Group, et al. International variation in the prevalence of COPD (the BOLD Study): a population-based prevalence study. Lancet. 2007;370(9589):741–750. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61377-4

- Standardization of Spirometry, 1994 Update. American Thoracic Society. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995; 152:1107–1136.

- Quanjer PH , Stanojevic S , Cole TJ , ERS Global Lung Function Initiative, et al. Multi-ethnic reference values for spirometry for the 3–95-yr age range: the global lung function 2012 equations. Eur Respir J. 2012;40(6):1324–1343. DOI:10.1183/09031936.00080312

- Quanjer PH , Pretto JJ , Brazzale DJ , et al. Grading the severity of airways obstruction: new wine in new bottles. Eur Respir J. 2014;43(2):505–512. DOI:10.1183/09031936.00086313

- Lamprecht B , Soriano JB , Studnicka M , et al. Determinants of underdiagnosis of COPD in national and international surveys. Chest. 2015;148(4):971–985. DOI:10.1378/chest.14-2535

- Schirnhofer L , Lamprecht B , Firlei N , et al. Using targeted spirometry to reduce non-diagnosed chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiration. 2011;81(6):476–482. DOI:10.1159/000320251

- Labonté LE , Tan WC , Li PZ , Can COLD Collaborative Research Group, et al . Undiagnosed chronic obstructive pulmonary disease contributes to the burden of health care Use. Data from the CanCOLD Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194(3):285–298. DOI:10.1164/rccm.201509-1795OC

- Zoia MC , Corsico AG , Beccaria M , et al. Exacerbations as a starting point of pro-active chronic obstructive pulmonary disease management. Respir Med. 2005;99(12):1568–1575. DOI:10.1016/j.rmed.2005.03.032

- Kate MJ , Stirling B , Shahzad G , et al. Characterizing undiagnosed chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Res. 2018;:19–26.

- From the Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2017. Available from:

- Herrera AC , de Oca MM , Varela MVL , et al. COPD underdiagnosis and misdiagnosis in a high-risk primary care population in four Latin American countries. A key to enhance disease diagnosis: The PUMA study. PLOS One. 2016; [April 13].

- Bastin AJ , Starling L , Ahmed R , et al. High prevalence of undiagnosed and severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at first hospital admission with acute exacerbation. Chron Respir Dis. 2010;7(2):91–97. DOI:10.1177/1479972310364587

- Bellamy D , Bouchard J , Henrichsen S , et al. International Primary Care Respiratory Group (IPCRG) guidelines: management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Prim Care Respir J. 2006;15(1):48–57. DOI:10.1016/j.pcrj.2005.11.003

- Bellamy D , Smith J . Role of primary care in early diagnosis and effective management of COPD. Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61(8):1380–1389. DOI:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01447.x

- Hankinson JL , Odencrantz JR , Fedan KB . Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general U.S. population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(1):179–187. DOI:10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9712108

- Penña VS , Miravitlles M , Gabriel R , et al. Geographic variations in prevalence and underdiagnosis of COPD: results of the IBERPOC multicentre epidemiological study. Chest. 2000;118(4):981–989. : DOI:10.1378/chest.118.4.981

- Miravitlles M , de la Roza C , Naberan K , et al. Problemas con el diagnóstico de la EPOC en atención primaria. [Attitudes toward the diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in primary care. Arch Bronconeumol. 2006; 42(1):3–8. DOI:10.1016/S1579-2129(06)60106-7

- Shin C , Lee S , Abbott RD , et al. Respiratory symptoms and undiagnosed airflow obstruction in middle-aged adults: the Korean health and genome study. CHEST. 2004;126(4):1234–1240. DOI:10.1378/chest.126.4.1234

- Stead LF , Bergson G , Lancaster T . Physician advice for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008; 2:CD000165.

- Halbert RJ , Natoli JL , Gano A , et al. Global burden of COPD: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2006;28(3):523–532. DOI:10.1183/09031936.06.00124605

- Meteran H , Miller MR , Thomsen SF , et al. The impact of different spirometric definitions on the prevalence of airway obstruction and their association with respiratory symptoms. ERJ Open Res. 2017; 3(4):00110-2017. DOI:10.1183/23120541.00110-2017