Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients have been known to have poor medication adherence rates. The purpose of this systematic review was to assess if outreach services could impact on medication compliance rates. CINAHL, Medline, Clinical Key and Cochrane library were all searched electronically along with grey literature for all eligible studies conducted on COPD patients in a non-acute hospital setting. Systematic review methodology was followed for data selection, extraction and risk of bias, validity testing and data analysis. Eight studies met all inclusion criteria. 4 randomised control trials and 4 quantitative intention-to-treat studies. 2 of the studies failed validity testing but due to a lack of articles, were included in the synthesis. Given the heterogeneity of data, a narrative synthesis was adopted. All 8 studies demonstrated the ability for an outreach service to improve medication adherence in the community setting. Secondary to this result, this systematic review showed the ability to reduce hospital admissions of exacerbations of COPD due to increased medication adherence. Quality of life was assessed but did not improve but importantly did not decrease. Medication adherence has the potential to be improved from an outreach programme but requires more high-quality research in the area to develop a standardised plan of care to identify the most effective way of educating patients on medication adherence. Medication adherence education should not be a once-off assessment, this systematic review has shown it must be continuous, re-checked and re-educated regularly.

Introduction

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is a common, preventable and treatable lung disease [Citation1]. COPD is identified by persistent respiratory symptoms and limited airflow due to alveolar and/or airway abnormalities caused by prolonged exposure and inhalation of harmful gases and toxins with progression varying between individuals [Citation1]. Exacerbations of COPD are identified as a flare-up of the most common respiratory symptoms of COPD: dyspnoea, cough and sputum production [Citation1].

It is estimated that Ireland has 500,000 people with COPD, however, only 110,000 of these have an official diagnosis of COPD [Citation2]. Ireland, currently, has the highest hospitalisation rate for COPD patients in Europe, with inpatient COPD care costing the state €70,813,40.00 annually [Citation2]. Presently, COPD is the 4th leading cause of death in Ireland [Citation3]. Exacerbations of COPD are the most common reason in Ireland currently for patient presentations to emergency departments [Citation4]. Globally, it is estimated there are 251 million cases of COPD worldwide; with 3.17 million deaths caused by COPD in 2015 [5]. However, it is believed the above death figure from COPD is significantly higher than this because as mentioned above, the amount of people with an official diagnosis of COPD and the actual number of people with COPD is vastly different [Citation1].

With such a high proportion of people with COPD globally, a COPD diagnosis has a major impact socioeconomically [Citation1]. COPD care in Europe equates to almost 56% of the total cost of all respiratory diseases within the healthcare budget [Citation6]. This is estimated at approximately €140 billion per year, with this figure is set to rise over the coming years, which is predicted to be crippling on the European health budget [Citation7]. Poland estimated that €55 million was spent by the government in 2012 in sick-pay and incapacity-to-work costs in 2012 alone [Citation7]. This particular study identified how costs can be reduced in the long-term disease management process if a diagnosis of COPD is confirmed and acted upon earlier [Citation7]. This particular statement is echoed by a Danish study showing the health-related cost of care for COPD patients was reduced from €6,121 to €5,909 when COPD was officially diagnosed [Citation8].

The availability of universal guidelines has made confirming a diagnosis of COPD quite straight-forward and helps health care professionals (HCPs) create individualised treatment plans based on recognised guidelines. Previous respiratory exacerbations and risk of further exacerbations should be taken into account to help provide a detailed diagnosis which will appropriately advise/guide HCPs on treatment plans and aim to improve both disease and symptom management.

The World Health Organisation define adherence as ‘the extent to which a person's behaviour - taking medication, following a diet, and/or executing lifestyle changes, corresponds with agreed recommendations from a health care provider’ [Citation9]. Compliance is often used as a substitute term for adherence [Citation10]. However, some view compliance as patients following clinician recommendations and not engaging in maintaining a relationship with HCPs [Citation10]. Chakrabarti [Citation10] does acknowledge that both terms ‘compliance and adherence’ are related to the behaviours of patients while taking medications, which allowed for the use of both terms in the literature search. Patients who have a prolonged poor adherence rate to their medications often result in increased health costs and poorer long-term health outcomes [Citation11]. One of the main reasons for poor/non-adherence to medications is the patients’ belief that they do not need these medications and their disease does not warrant medication [Citation12]. COPD patients have been shown to be notorious for poor/non-adherence to medications, treatments and interventions [Citation13]. One study showed adherence rates and correct inhaler techniques were as low as 6% [Citation14]. Over 30% of COPD patients were non-adherent to any medications and importantly, another 25% of patients attempted to be adherent to medications but had a poor technique, therefore not receiving any benefit from their medication [Citation14]. The introduction of education sessions and community interventions to improve adherence was identified as a positive resolution to this issue [Citation13].

The GOLD 2019 report offers HCPs a step-up treatment plan when current treatment is no longer effective at improving symptoms or exacerbations are increasing [Citation1]. However, if a treatment is being deemed ineffective and HCPs are unaware of a patient’s poor adherence, patients may have their treatment stepped-up unnecessarily causing polypharmacy. Polypharmacy carries its own risks including increased drug interaction risks, hospitalisation and potentially inappropriate medication prescribing [Citation15]. If patients are adherent to medication but have poor technique (it is known 50% of COPD patients have poor technique), their treatment may be increased unnecessarily, when a simple intervention such as medication education/assessment may have sufficed [Citation16]. One previous systematic review on this topic was completed focussing on interventions completed by pharmacists only [Citation17]. Given the approach to care delivery in Ireland is based on multi-disciplinary team care and a lack of available systematic reviews focussing on multi-disciplinary team approach to medication adherence in the community, it is necessary to investigate this further.

The aim of this systematic review is to determine the impact of an outreach service on medication adherence for COPD patients.

Materials and methods

Review question: What is the impact of an outreach service on medication adherence for COPD patients?

The review question was formulated using the PICO framework:

P - Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease patients

I – The provision of an outreach/out-of-hospital service/facility

C- Standard or usual care

O – Medication Adherence

For the purpose of this review, an outreach service is classed as the provision of interventions such as information sessions/tutorials/class to COPD patients by HCPs on disease and medication management and assessment of same. This can be completed in outpatient clinics/home/local pharmacies; once the participant is not a current inpatient. This definition is in line with HSE COPD Outreach guide for clinicians [Citation18].

Study design

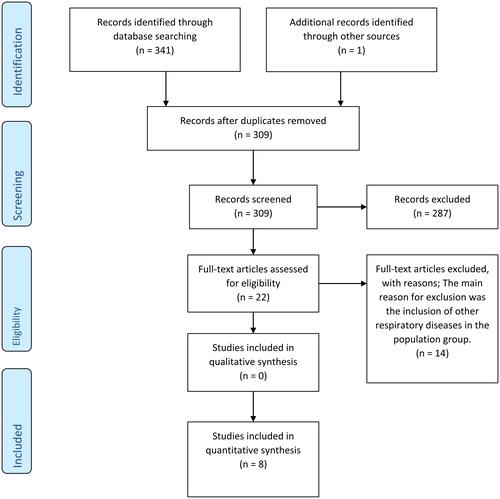

This systematic review was undertaken with adherence to the principles of the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) [Citation19]. All articles were of quantitative design or randomised control trials (RCTs). No suitable qualitative studies were found.

Search strategy

The following databases were searched CINAHL; Medline; Clinical Key and The Cochrane Library. The following terms were used for the search strategy: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease/COPD; medication compliance/medication adherence; outpatients/outpatient-service/outreach/out-of- hospital/community interventions. Medical Subject Headings were also used in the relevant databases to explore all available data. These search terms were used in various combinations in the databases to standardise searching. PRISMA flow diagrams were created for each database search [Citation19]. The information from each individual PRISMA was merged to form an overall PRISMA flow diagram. The GOLD website was searched for worldwide reports, statistics, standards and relevant reference points. The HSE Lenus database was searched for available Irish research. The reference lists of the studies identified for review were searched for any other relevant studies. No limitations were put on year of publication to include all available literature. Authors of papers were emailed if necessary, to see if data were published or availability of trial results if unable to locate same online. A PRISMA checklist was used as guidance throughout the systematic review (See Supplementary File 1). The search strategy for databases is included as Supplementary File 2).

Inclusion criteria

Studies included in this systematic review had to have participants with a confirmed diagnosis of COPD in line with the GOLD report classifications. The intervention was run by a HCP (clinician, nurse, pharmacist, physiotherapist, trained carer aid). Due to a lack of translation services only English language studies were included. All included studies were original research of quantitative design and peer-reviewed.

Exclusion criteria

Studies which included participants with other respiratory illnesses were excluded. Studies which reported on patients who were inpatients during the intervention period were excluded. Any literature reviews were also excluded.

Primary and secondary outcomes

The primary outcome measured was medication adherence in COPD patients. The secondary outcomes measured were quality of life (QOL), exacerbations of COPD requiring hospital admission, disease knowledge and medication optimisation.

Data extraction

Once all studies suitable for inclusion were retrieved from the search strategy, a comprehensive data extraction table was drawn up on the basis of Noyes and Lewin [Citation20] and Bettany-Salticov [Citation21]. The following titles were included in the table: author, year, title, source, aim, design, country of origin, setting, duration, sample size, intervention, primary outcome, secondary outcomes, analysis, results, recommendations/conclusions and evidence-based librarianship (EBL) score. The data extraction table was verified and validated by a second reviewer in line with best practice for systematic reviews [Citation20].

Data analysis

A meta-analysis is usually advised when RCTs are involved [Citation22], however, the results of the included studies were more suited to a narrative synthesis due to their heterogeneity. The aim of the intervention was the same in each article, however, the method of intervention varied between articles. Completing a narrative synthesis allowed for the combination of statistical and non-statistical data together in similar studies for a valid, overall synthesis [Citation23]. A narrative synthesis was decided upon as many have recommended its use in systematic reviews assessing the impact or effect of an intervention, similar to this systematic review [Citation24]. Narrative synthesis in systematic reviews are becoming more recognised and respected in regards their validity and power [Citation25].

Quality appraisal

All included studies were reviewed by a second independent researcher to validate studies and reduce the risk of bias. All included studies were subjected to a risk of bias assessment. This was performed by completing an EBL quality appraisal checklist developed by Glynn [Citation26]. Both RCTs and quantitative studies are included in this systematic review, and given the two different study designs, an EBL checklist was decided as the preferred method for quality appraisal for continuity reasons. The use of Revman was considered for assessment of bias in RCTs but as this would not include all studies in this systematic review, the EBL checklist was used to provide homogeneity. This was done in conjunction with the second reviewer. Articles with an EBL checklist score of ≥75% were deemed as a valid study [Citation26].

Results

As can be seen in , 309 records were assessed for inclusion once duplicates were removed. Initial screening excluded 287 articles as they did not meet the inclusion criteria or were inappropriate for this systematic review. The main reason for exclusion was the inclusion of other respiratory diseases in the population group. This left 22 articles for further review. On review of each of the full texts 14 did not meet the predetermined criteria for inclusion. 4 RCTs and 4 quantitative studies were identified for inclusion. No qualitative studies were found ().

Table 1. EBL scores.

Methodological quality of included studies

Each included article was subjected to an EBL checklist to determine validity. includes section-specific EBL scores for each included article. Two articles did not meet overall validity [Citation27, Citation28]. Although they were deemed invalid it was decided to include these studies to demonstrate the quality of evidence available on this topic and due to the low number of appropriate articles.

Table 2. Included and excluded studies.

In Section A 5/8 studies achieved the >75% validity score [Citation29–33]. The remaining 3 studies all achieved a validity score of 66% or less making them not valid in regards to population [Citation27, Citation28, Citation34].

Included articles scored quite poorly for Section B with 5/8 articles not valid [Citation27, Citation28, Citation30, Citation33, Citation34]. 3 studies had a validity score of >75% [Citation29, Citation31, Citation32]

All 8 articles scored 100% validity in Section C. This section is related to study design and it is reasonable to say from this, the study designs of RCT and quantitative design were an appropriate design for the investigation of this intervention.

In section D of the EBL checklist, 3/8 articles achieved a non-valid score [Citation27, Citation28, Citation31]. 5/8 articles achieved the required validity score of above 75% [Citation29, Citation30, Citation32–44].

Overview of included studies

A data extraction table was populated providing an overview of included studies based on guides by Bettany-Salticov [Citation21] and Noyes and Lewin [Citation20] (see ). A separate table (Table 3) with each article’s inclusion/exclusion criteria is included.

Four studies were RCTs and four studies were intention-to-treat quantitative studies. All studies were completed in the community, with the place of intervention varying: outpatient clinics; community pharmacies; HCPs providing interventions in the participants home. However, home visits were the least used location and often in lieu of a home visit, follow-up phone calls were provided. Damps-Konstanska et al. [Citation29] had the smallest sample size with 30 participants while Tommelein et al. [Citation32] had the largest sample size at 692 participants. Average sample size worked out at 162.12 participants per study. Five studies were conducted in Europe with the others conducted in Japan, China and Jordan. The most commonly used tool was the St. George Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ). This tool is a quality of life tool which includes questions on medication adherence. Five studies used SGRQ as a measurement tool [Citation28–31, Citation33] Damps-Konstańska et al. [Citation29] was the only study to not complete a repeat SGRQ post-intervention.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome of this systematic review was patients’ adherence to medication post an outreach intervention. All included studies measured the impact of an outreach service on medication adherence for COPD patients in some form. 3 of the included studies measured medication adherence as a secondary outcome [Citation27, Citation29, Citation30]. No exclusion criteria were set as to whether adherence was measured as a primary or secondary outcome allowing these papers for inclusion.

All included studies had figures and statistics on the impact of medication adherence techniques except for Alton and Farndon [Citation27], who descriptively documented their results, providing very few documented figures. Participants received on average 2.9 visits. First visit was the study’s commencement where an assessment, review and education on medication and their disease was provided by a pharmacist. If necessary, they could liaise with a GP if medication changes were appropriate. The 2nd visit at 3 months reassessed technique, provided support and offered an extra telephone call if needed. At 6 months, the final visit was a final adherence assessment. Others received a follow-up phone call only. It was clear following assessment that most participants did not know how to use inhalers prior to the intervention.

Repeat COPD Assessment Test scores were only completed on some participants. Alton and Farndon [Citation27] described how the intervention improved medication adherence as most participants did not know how to use and take their medication correctly prior to commencing the study and post intervention there was a notable improvement in medication optimisation, which in turn improved adherence.

Two studies reported on the impact of a medication adherence intervention using confidence intervals [Citation32, Citation34]. Both studies used a confidence interval of 95%. van Boven et al. [Citation34] showed an improvement in adherence to both long acting bronchodilators (0.85-0.86) and inhaled corticosteroids (0.82-0.84) post-intervention. Additionally, differences for both bronchodilators (0.01 [95% CI: −0.04-0.06]) and ICS (0.03 [95% CI:-0.04-0.10]), were not significant.

In Tommelein et al.’s study [Citation32], the intervention group had a significantly improved adherence score in comparison with the control group. Mean medication adherence scores were 82.7 (SD =23.9) in the control group and 84.0 in the intervention group at baseline. Furthermore, at 3 months, Tommelein et al., detected a significantly greater improvement from baseline in the intervention group compared to the control group (Δ, 8.51; 95% CI, 4.63–12.4; p < 0.0001).

The remaining studies reported results using p-values [Citation28, Citation31–33]. Tommelein et al. [Citation32] also provided p-values for the impact of their intervention on medication adherence. All 6 studies reported a p-value of <0.05 as a significant result. All studies reported a p-value of significant impact for an improvement in medication adherence post-intervention.

Damps-Konstańska et al. study aimed to determine whether a short education programme can adherence in 30 patients. At the beginning of the study, the patients’ knowledge of COPD and adherence was highly unsatisfactory yet post intervention a p-value of 0.00 was reported for improving adherence [Citation29]. Takemura et al. examined the effect of a network system for providing proper inhalation technique in 55 COPD patients, Patient’s outcomes were recorded both prior to the system and 4 years later. Adherence to the inhalation regimen increased significantly (4.1 ± 0.7 versus 4.4 ± 0.8, p = 0.024) [Citation28]. Khdour et al. investigated the impact of a disease and medicine management programme focussing on self-management in 259 patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 86 patients were randomly assigned to an intervention group and 87 to a usual care group. There was a significant difference between the intervention and usual care groups regarding adherence to medication (77.8% vs. 60.0%, p = 0.019) [Citation31]. Tommelein et al.’s [Citation32] 3 month RCT assessed the effectiveness of a pharmaceutical care programme for patients with COPD in 170 community pharmacies in Belgium. At the end of the trial the medication adherence (Δ,8.51%; 95% CI, 4.63–12.4; p < 0.0001) scores were significantly higher in the intervention (n = 371) group compared with the control group (n = 363). Jarab et al. evaluated the impact of a pharmaceutical care intervention, with a strong focus on self-management, on a range of clinical and humanistic outcomes in patients with COPD within an Outpatient COPD Clinic at the Royal Medical Services Hospital. A total of 66 patients were randomised to the intervention group and 67 patients were randomised to the control group. At the end of their 6-month RCT Chi-squared analysis revealed a significant decrease in the proportion of non-adherent patients in the intervention group when compared with the control group (28.6% vs. 48.4%) at the 6 month assessment (p < 0.05; [Citation30].

Wei et al. recorded 3 different p-values as they measured adherence at different stages throughout their trial [Citation33]. The intervention took place over 6 months, and at the 12 months mark, participants were followed-up to assess the longer impact of the intervention once active involvement was stopped. Interestingly, at 1 month, Wei et al. had a negative p-value of 0.142 [Citation33]. At the 6-month point, adherence was measured again and now it was clear the intervention had a significant impact on medication adherence with a p-value of 0.016. At 12 months, when no active intervention had taken place in 6 months, medication adherence still was improved with a p-value of 0.039. It is slightly raised from the previous p-value at 6 months but it shows the significant long-term, continued impact of their intervention on medication adherence for COPD patients. Constant, long-term follow-up, regular re-training and re-assessment are necessary for COPD patients to prevent a loss of skills and reduction in adherence.

Secondary outcomes

Quality of life

All 8 studies measured the impact of medication adherence on QOL using various tools. 4 studies used SGRQ to measure the impact of the intervention on QOL [Citation28, Citation30, Citation31, Citation33]. Damps-Konstańska et al. used SGRQ, however only measured QOL pre-intervention and not post, not providing any comparable data [Citation29]. All 4 studies at the end of their intervention showed improvement but none of were deemed significant on the overall SGRQ QOL score [Citation28, Citation30, Citation31, Citation33]. Khdour et al. [Citation31] measured overall SGRQ scores at 6 months and showed a significant improvement in scores. However, by 12 months, on reassessment it was no longer significant. SGRQ contains subgroups, and at the end of the intervention, some SGRQ subgroup measurements in 2 articles showed significant improvement (symptoms of COPD and impact of COPD on daily life) [Citation31, Citation33]. This improvement was not enough to influence SGRQ total scores.

Two studies used COPD Assessment Test scores to measure QOL [Citation27, Citation32]. COPD Assessment Test scores improved for Alton and Farndon [Citation27] but no improvement noted for Tommelein et al. [Citation32]. However, it must be noted not all of Alton and Farndon’s [Citation27] participants completed COPD Assessment Test questionnaires and Tommelein et al. [Citation32] had a much higher sample size.

The mMRC scale was used by van Boven et al. [Citation34], and as a second measurement by Tommelein et al. [Citation32] but neither study could demonstrate their intervention caused any improvement in QOL.

Exacerbations of COPD causing hospital admission

Five studies measured the impact of a medication adherence programme on the number of exacerbations of COPD causing hospitalisation [Citation30–34]. Alton and Farndon reported one patient avoided hospitalisation due to their intervention [Citation27]. Using t-values and confidence intervals van Boven et al. showed a reduction in hospital admissions due to exacerbations of COPD, but scores not of significant difference [Citation34]. Wei et al. [Citation33] showed the intervention group had a 56% reduction in hospital admissions for exacerbations of COPD and a significant reduction in the frequency of hospitalisations per year for COPD patients. Similarly, Khdour et al.’s [Citation31] RCT showed a significant reduction in hospital admissions for the intervention group, with only 26 requiring hospitalisation in the intervention group compared with 64 in the control group (p-value 0.01). It is worth noting Khdour et al. also recorded a significant decrease in bed-days for those patients who were hospitalised (control group 466 bed-days; intervention group 164 bed-days) [Citation31]. Tommelein et al. showed their adherence intervention caused a reduction in hospitalisation when compared with the control group (9 in the intervention group and 35 in the control group) [Citation32].

From this Tommelein et al. predicted a significant annual 72% reduction in hospitalisation for the intervention group (p-value 0.003) [Citation32]. Jarab et al. had a significant reduction in hospitalisation rates due to exacerbations of COPD in the intervention group with only 4.5% of participants requiring hospitalisation in comparison to 16.4% of control participants (p-value 0.031) [Citation30]. The ability to reduce the amount of COPD patients requiring hospital admission is both cost-effective and reduces disease burden on society.

Disease knowledge

Three studies measured the impact of an outreach service on participants knowledge of COPD [Citation29–31]. All 3 studies noted all participants, including control participants [Citation30, Citation31] had either poor or fair disease knowledge prior to any intervention. For participants who received interventional care, there was a significant improvement in their knowledge of COPD. Jarab et al. noted the control group had no increase in knowledge and knowledge-scores remained similar in the control group at the end of the study [Citation30]. Interestingly, Khdour et al. noticed a dis-improvement at the end of the trial (12 months in duration) in the control group’s COPD knowledge [Citation31]. Damps-Konstańska et al. remarked how patients’ awareness of disease self-management increased at the end of the intervention [Citation29].

Medication optimisation

Two studies looked at how an outreach programme could improve medication optimisation [Citation27, Citation34]. Alton and Farndon reported 4 patients had their medication changed to a drug more suitable for their COPD management during the intervention [Citation27]. van Boven et al. provided a GP assessment for all patients on commencement of the study to allow for medication optimisation for these patients [Citation34].

Discussion

The above results have shown that an outreach service has the ability to improve medication adherence in COPD patients in the community. This finding was supported in all 8 articles. Secondly, a COPD outreach service also had the ability to reduce hospital admissions for exacerbations of COPD. Although, it did not improve QOL for COPD patients, their QOL did not deteriorate while participating in these studies. These studies did not show an effect on patients’ knowledge of their disease or medication optimisation unfortunately.

Blakey et al. [Citation35] state that as HCPs it is important to provide respiratory patients with all available resources; the chance to offer patients the best care; and afford them the opportunity to self-manage their disease under responsible supervision. The aim of completing this systematic review was to examine the impact of an outreach service on medication adherence in COPD patients.

As can be seen from this narrative synthesis, an outreach programme has the potential ability to improve adherence in this patient group. In 2014, Zhong et al. [Citation17] completed a systematic review on pharmacists’ impact on improving medication adherence in the community for COPD patients. Zhong et al. showed pharmacists were beneficial in improving medication adherence for COPD [Citation17]. However, because, outreach care in Ireland involves a multi-disciplinary team approach, this led to an attempt to extend on Zhong et al. [Citation17] systematic review and try find strong literature to support Blakey et al.’s [Citation35] statement.

It can be seen from the results, an outreach programme has the potential to improve medication adherence in COPD patients. An extensive literature search yielded 8 suitable articles for inclusion. The 8 studies yielded were of 2 different designs. There was a number of different interventions within these studies to measure the impact of an outreach service on medication adherence for COPD patients. All 8 studies measured medication adherence with 3 studies [Citation27, Citation29, Citation30] measuring adherence as a secondary outcome.

Each of the studies in this systematic review proved the potential of their intervention to improve medication adherence, however, the strength of evidence varied between articles. Alton and Farndon provided no statistical evidence, only statements that their intervention improved adherence [Citation27]. van Boven et al. provided evidence that their outreach intervention could improve adherence yet, was not statistically proven/supported [Citation34].

All studies were subjected to validity scores to assess quality and risk of bias. Two studies failed overall validity [Citation27, Citation28]. Studies with non-valid EBL checklist scores must be interpreted with caution as it can mean the level of evidence provided in the particular study is not necessarily of high quality [Citation26]. With Alton and Farndon [Citation27], the lack of statistical evidence provided by them left their results harder to compare and interpret in relation to the other included studies. This correlates to the study’s poor EBL score (65.2%), leaving the evidence from this study of low weighting in regards to influencing outcomes and recommendations. Takemura et al.’s [Citation28] EBL checklist score was slightly higher at 66.6%, however it is still a non-valid study and its results, although significant must be interpreted with caution.

Even though all studies assessed medication adherence for COPD patients, there is heterogeneity within the 8 articles. There is no common intervention in all included studies and as discussed earlier there are a number of different methods used to measure adherence by the various researchers. The majority of studies in this systematic review [Citation28, Citation30–34], created personalised plans for the participants, encompassing medication timings, techniques, action plans when unwell and useful contact numbers as part of their intervention. Given that no studies use the same intervention protocol, it is very hard to pinpoint a particular outreach intervention that was most beneficial. These studies all reported positive outcomes, many with p-values of significant impact. The positive results when using personalised plans are in line with recommended practice by the Irish College of General Practitioners and is still the current recommendation however many COPD patients are not in possession of personalised plans or have an outdated version [Citation36].

Wei et al. followed participants in the 6 months of intervention, along with 6 months post-intervention [Citation33]. At the end of active intervention, a significant improvement in medication adherence for participants was detected (p-value 0.016). When reassessed after 6 months of no active intervention the p-value has started to decrease (0.039) – implying adherence was decreasing. There is no definite reason as to this, but it is reasonable to suggest that in the 2nd 6 months once participants stopped regular contact with HCPs, the risk of non-adherence increased due to a lack of contact. A recurrent theme in all 8 studies was regular contact with a HCP throughout the intervention who had a deep knowledge of COPD. However, the form of contact varied between studies leaving it harder to draw a conclusion as to the best form of contact by a HCP. It can be said though, regular contact can improve medication adherence.

This statement is echoed by Conn et al. [Citation37] whose systematic review identified that those at high risk of non-adherence, regular face-to-face contact and personalised plans were of critical importance and as Duarte-de-Araújo et al. [Citation12] discussed, adherence is a challenging issue for COPD patients. It is imperative well-supported, proven programmes are developed to normalise adherence for our COPD patients.

The following secondary outcomes were measured QOL, exacerbations of COPD causing hospital admission, disease knowledge and medication optimisation. QOL was measured in all studies, but no intervention proved to have significant impact in improving QOL. COPD is a non-curable disease and maintaining QOL for these patients is important to long-term disease management [Citation4]. Studies on an outreach’s programme impact on medication adherence were unable to show a significant impact on COPD patients’ QOL. Mitsiki et al. identify a holistic approach is necessary to improve QOL for COPD patients [Citation38]. This systematic review only looks at one intervention (an outreach programme’s impact on medication adherence) and to understand an outreach programme’s true effect on QOL, it would need to be measured in conjunction with other outreach interventions.

Five studies measured how medication adherence affected exacerbations of COPD requiring hospital admission and demonstrated positive results. Significant decreases in hospital admissions were obtained in 4 studies [Citation30–33]. van Boven et al. [Citation39] showed a reduction in cost of COPD care due to medication adherence based on Tommelein et al.’s [Citation32] results. It cannot be assumed that all studies had the same cost-saving impact but in a society where healthcare and healthcare initiatives are dominated by budgets, any potential, promising, cost-saving interventions must be considered.

Disease knowledge and medication optimisation were not as commonly reported in the included articles but did present positive results. The studies which measured disease knowledge noted improved self-awareness and understanding of COPD [Citation29, Citation31]. A long-term goal for patients in self-managing chronic illnesses is to be competent in their own disease knowledge [Citation40]. Two studies reported on medication optimisation, however, there was little data provided by these studies to allow their results to be of significant impact in the overall discussion.

Limitations

The author recognises there are limitations to this systematic review. There was a lack of available research causing two different research designs to be used. The use of two different designs provided heterogeneity which made data comparison more difficult and meta-analysis impossible. Intention-to-treat studies are seen to be of lesser quality and of higher risk of bias due to the lack of a control [Citation41]. Ideally, one study design would be used, however, given the lack of available articles studies of all quantitative design were included. A risk of bias assessment using the EBL was carried out on all articles prior to analysis.

Given the lack of research, the author could not narrow down the systematic review to one outreach intervention which attempted to impact medication adherence, further increasing the heterogeneity and limiting the results and ability to provide detailed recommendations.

Another limitation of this systematic review was no criteria were placed on the disease severity of patients that were included in the studies. Patients of varying GOLD classifications were included. As COPD progresses, medication burden increases with daily tasks becoming harder and this may have been influential on results. In the exclusion criteria the author had to exclude full text articles not of English language as there was no funding available for translation services.

Conclusion

An outreach service involving HCPs has the potential to positively impact medication adherence in COPD patients. However, from this review there is no defined pathway or single intervention that can be identified as the cause for medication adherence. This systematic review showed there is a shortage of published research on this topic. In the available articles there is a risk of bias in some, however that is acknowledged in this systematic review. Along with improving medication adherence, outreach services can reduce hospital admissions, in turn reducing COPD-related bed days and inpatient COPD costs. Given the promising results, further high-quality research, particularly RCTs are needed to examine the full impact a HCP-led outreach service has on medication adherence in COPD patients.

Disclosure of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (344.5 KB)Supplemental Material

Download PDF (194.4 KB)Supplemental Material

Download PDF (315.3 KB)References

- GOLD Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. 2019 Global Strategy for Prevention, Diagnosis and Management of COPD 2018. https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/GOLD-2019-v1.7-FINAL-14Nov2018-WMS.pdf. Accessed 10th January, 2019.

- RCPI, Royal, College, et al. COPD National Collaborative Pilot Report 2018.

- National Office of Clinical Audit. National Audit of Hospital Mortality Annual Report 2017 2018 [cited 15 Jan 2019]. Available from: http://s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/noca-uploads/general/National_Audit_of_Hospital_Mortality_Annual_Report_2017_FINAL.pdf. .

- Irish Thoracic Society. Respiratory Health of the Nation – 2018 2018 [cited 12 Jan 2019]. Available from: https://irishthoracicsociety.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/RESP-Health-LATEST19.12.pdf.

- World Health Organisation (WHO). Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease – factsheet. 2017 [cited 12 Jan 2019]. Available from: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-. (copd) .

- Forum of International Respiratory Societies. The global impact of respiratory diseases. 2nd ed. 2017 [cited 16 Jan 2019]. Available from: http://www.firsnet.org/images/publications/The_Global_Impact_of_Respiratory_Disease.pdf .

- Wziątek-Nowak W, Gierczyński J, Dąbrowiecki P, et al. Socioeconomic effects of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease from the public payer’s perspective in Poland. In: Pokorski M, ed. Respirology. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2016; p. 53–66.

- Løkke A, Hilberg O, Tønnesen P, et al. Health, social and economic consequences of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): a controlled national study. Eur Respir J. 2012;40(Suppl 56):P995.

- World Health Organisation WHO. Adherence to long-term therapies – evidence for action 2003 [cited 14 Jan 2019]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Js4883e/. .

- Chakrabarti S. What's in a name? Compliance, adherence and concordance in chronic psychiatric disorders. World J Psychiatry. 2014;4(2):30–36. DOI:10.5498/wjp.v4.i2.30

- Gregoriano C, Henny-Reinalter S, Maier S, et al. Patients' adherence to chronic treatment in lung diseases: preliminary data from a randomized controlled trial. Eur Respir J. 2016;48(Suppl 60):PA1038. DOI:10.1183/13993003.congress-2016.PA1038

- Duarte-de-Araújo A, Teixeira P, Hespanhol V, et al. COPD: understanding patients' adherence to inhaled medications. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018;13:2767–2773. DOI:10.2147/COPD.S160982

- Blackstock FC, ZuWallack R, Nici L, et al. Why don't our patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease listen to us? The enigma of nonadherence. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(3):317–323. DOI:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201509-600PS

- Sulaiman I, Cushen B, Greene G, et al. Objective assessment of adherence to inhalers by patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(10):1333–1343. DOI:10.1164/rccm.201604-0733OC

- Gutierrez-Valencia M, Izquierdo M, Malafarina V, et al. Impact of hospitalization in an acute geriatric unit on polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate prescriptions: A retrospective study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2017;17(12):2354–2360. DOI:10.1111/ggi.13073

- Sanduzzi A, Balbo P, Candoli P, et al. COPD: adherence to therapy. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2014;9(1):60–60. DOI:10.1186/2049-6958-9-60

- Zhong H, Ni X-J, Cui M, et al. Evaluation of pharmacist care for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Clin Pharm. 2014;36(6):1230–1240. DOI:10.1007/s11096-014-0024-9

- Health Service Executive. COPD Outreach Programme: Model of Care 2011 [cited 10 Jan 2019]. Available from: https://www.hse.ie/eng/services/publications/clinical-strategy-and-programmes/copd-outreach-scheme-model-of-care-2011.pdf.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, PRISMA Group, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097 DOI:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Noyes J, Lewin S, et al. Chapter 5: extracting qualitative evidence. In: Noyes J, Booth A, Hannes K, editors. Supplementary guidance for inclusion of qualitative research in Cochrane systematic reviews of interventions. 2011.

- Bettany-Salticov JM, R. How to do a systematic literature review. A stepby-step guide. 2nd ed. New York: Open University Press; 2016.

- Moore Z. Meta-analysis in context . J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(19-20):2798–2807. V DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04122.x

- Gough D, Oliver S, Thomas J. An introduction to systematic reviews. 2nd ed. London: Sage; 2017.

- Popay J, Roberts HM, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. London: Institute for Health Research; 2006.

- Noyes J, Hannes K, Booth A, et al. Chapter QQ: Qualitative and implementation evidence and Cochrane reviews. In: Higgins J, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. The Cochrane Collaboration 2013.

- Glynn L. A critical appraisal tool for library and information research. Library Hi Tech. 2006;24(3):387–399. DOI:10.1108/07378830610692154

- Alton S, Farndon L. The impact of community pharmacy-led medicines management support for people with COPD. Br J Commun Nurs. 2018;23(6):214–219. DOI:10.12968/bjcn.2018.23.6.214

- Takemura M, Mitsui K, Ido M, et al. Effect of a network system for providing proper inhalation technique by community pharmacists on clinical outcomes in COPD patients. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2013;8:239–244. DOI:10.2147/COPD.S44022

- Damps-Konstańska I, Werachowska L, Krakowiak P, et al. Acceptance of home support and integrated care among advanced COPD patients who live outside large medical centers. Appl Nurs Res. 2016;31:60–64. DOI:10.1016/j.apnr.2015.12.003

- Jarab AS, Alqudah SG, Khdour M, et al. Impact of pharmaceutical care on health outcomes in patients with COPD. Int J Clin Pharm. 2012;34(1):53–62. DOI:10.1007/s11096-011-9585-z

- Khdour MR, Kidney JC, Smyth BM, et al. Clinical pharmacy-led disease and medicine management programme for patients with COPD. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;68(4):588–598. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03493.x

- Tommelein E, Mehuys E, Van Hees T, et al. Effectiveness of pharmaceutical care for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (PHARMACOP): a randomized controlled trial. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;77(5):756–766. DOI:10.1111/bcp.12242

- Wei L, Yang X, Li J, et al. Effect of pharmaceutical care on medication adherence and hospital admission in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): a randomized controlled study. J Thorac Dis. 2014;6(6):656–662. DOI:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.06.20

- van Boven JFM, Stuurman-Bieze AGG, Hiddink EG, et al. Effects of targeting disease and medication management interventions towards patients with COPD. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32(2):229–239. DOI:10.1185/03007995.2015.1110129

- Blakey JD, Bender BG, Dima AL, et al. Digital technologies and adherence in respiratory diseases: The road ahead. Eur Respir J. 2018;52(5):1801147. DOI:10.1183/13993003.01147-2018

- ICGP Irish College of General Practitioners. Management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in general practice. Dublin: ICGP; 2009.

- Conn VS, Ruppar TM, Enriquez M, et al. Medication adherence interventions that target subjects with adherence problems: systematic review and meta-analysis. Res Social Adm Pharm: RSAP. 2016;12(2):218–246. DOI:10.1016/j.sapharm.2015.06.001

- Mitsiki E, Kazanas K, Hatziapostolou P. Quality of life and disease burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients in Northern Greece – The INCARE* study. Eur Respir J. 2015;46(suppl 59):PA3854.

- van Boven JF, Tommelein E, Boussery K, et al. Improving inhaler adherence in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Respir Res. 2014;15(1):66 DOI:10.1186/1465-9921-15-66

- Cramm JM, Nieboer AP. Disease management: the need for a focus on broader self-management abilities and quality of life. Popul Health Manag. 2015;18(4):246–255. DOI:10.1089/pop.2014.0120

- Emerson RW. Measuring change: pitfalls in research design. J Vis Impair Blind. 2016;110(4):288–290. DOI:10.1177/0145482X1611000412