Abstract

The results reported by different studies on telemonitoring in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have been contradictory, without showing clear benefits to date. The objective of this study was to ascertain whether an early discharge and home hospitalization telehealth program for patients with COPD exacerbation is as effective as and more efficient than a traditional early discharge and home hospitalization program. A prospective experimental non-inferiority study, randomized into two groups (telemedicine/control) was conducted. The telemedicine group underwent monitoring and was required to transmit data on vital constants and ECGs twice per day, with a subsequent telephone call and 2 home visits by healthcare staff (intermediate and at discharge). The control group received daily visits. The main variable was time until first exacerbation. The secondary variables were: number of exacerbations; use of healthcare resources; satisfaction; quality of life; anxiety-depression; and therapeutic adherence, measured at one and 6 months of hospital discharge. A total of 116 patients were randomized (58 to each group) without significant differences in baseline characteristics or time until first exacerbation, i.e. median 48 days (pp. 25–75:23–120) in the control group, and 47 days (pp. 25–75:19–102) in the intervention group; p = 0.52). A significant decrease in the number of visits was observed in the intervention versus the control group, 3.8 ± 1 vs 5.1 ± 2(p = 0.001), without significant differences in the number of exacerbations. In conclusion follow-up via a telemedicine program in early discharge after hospitalization is as effective as conventional home follow up, being the cost of either strategy not significantly different.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is one of the leading causes of chronic-disease-related morbidity and disability worldwide [Citation1,Citation2], and its prevalence is increasing [Citation3]. Despite underdiagnosis [Citation4] of the disease in Spain, a number of epidemiologic studies have reported that it affects around 8-10% of the adult population.

The natural history of COPD is markedly influenced by exacerbations, defined as, episodes of worsening of respiratory symptoms accompanied by a change in treatment [Citation5,Citation6], causing swifter clinical and functional deterioration, and associated with an increase in mortality [Citation7–9].

The economic and social repercussions of COPD are considerable. In Spain, according to the cost analysis contained in the document issued by the Ministry of Health, Social Services & Equality, and entitled, “COPD strategy in the National Health System” (Estrategia en COPD del Sistema Nacional de Salud), the mean direct cost per patient is € 1,712 − 3,238 per year, made up of hospital costs (40-45%), drugs (35-40%), and medical visits and diagnostic tests (15–25%) [Citation2,Citation10].

Healthcare models that make use of new technologies increase the efficiency of healthcare services and enhance quality of life. Their use could rationalize healthcare costs without worsening healthcare quality, while also achieving more humanized care in the patient’s socio-family environment [Citation1].

Different strategies have been studied [Citation11,Citation12], ranging from telematic follow-up of stable patients with advanced COPD for early detection and treatment of exacerbations, to home hospitalization in cases of acute exacerbation [Citation13], or follow-up with telemedicine after early hospital discharge [Citation14].

The use of this technique has been addressed by various systematic reviews [Citation15–19], yet despite its presumable potential, in no case has sufficient evidence been found for considering it cost-effective, possibly due to the heterogeneity of the different studies.

Accordingly, the aim of this study was to conduct a clinical trial to evaluate the effectiveness/efficiency of and satisfaction with a home telemedicine program focusing on patients with COPD exacerbation after early hospital discharge, and compare it with early discharge and follow-up with traditional home hospitalization.

Material and methods

The TELEMED-COPD study consisted of a randomized clinical trial with 2 parallel groups, both with early discharge: first, an intervention group that underwent home hospitalization with telemonitoring; and second, a control group that underwent traditional follow-up based on face-to-face visits by healthcare staff. The trial was conducted at the Puerta de Hierro University Teaching Hospital from March 2012 through July 2018. Once informed consent had been obtained from the participants, the latter were randomly distributed between the two groups, using a computer-generated table of pseudo-randomized numbers in variable blocks. The randomization sequence was kept concealed by the randomization system itself. Patients who withdrew from the study were not replaced.

The trial complied with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Puerta de Hierro University Teaching Hospital (Acta 276). Data confidentiality was guaranteed under the provisions of the 1999 Personal Data Protection Act (Ley Orgánica de Protección de Datos 15/1999), and the trial was registered in Clinical Trials.gov (Identifier NCT01951261).

Participation criteria

The definition used for study purposes was as follows: any patient admitted with COPD exacerbation to the Pneumology Department, with no age limit, who, after an initial phase of clinical stabilization not exceeding 4 days, met the following inclusion criteria: 1) diagnosis of COPD (prior to or during admission according to the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease/GOLD) [Citation20]; 2) absence of concomitant severe decompensated diseases; 3) arterial gasometry: pH >7.35, pO2 >50 mmHg, with O2 at a maximum of 3 lpm, and oxygen saturation >90%, pCO2 <55; 4) afebrile for more than 48 h; 5) need of administration of bronchodilators a maximum of every 6 h; 6) corticosteroids <40mg/12 hs; 7) chest radiography without new-onset pathology; 8) subjective improvement; and, 9) appropriate family environment.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) presence of end-stage neoplasm or other terminal chronic disease; 2) alcoholism; 3) need of intravenous medication; 4) inability to understand and participate in the program; 5) having required ICU care or need of noninvasive mechanical ventilation during exacerbation; and, 6) institutionalized patient.

The criteria for withdrawal were: supervening incapacity to use telemonitoring; complications leading to hospital admission which occurs after early discharge, while the patient is assisted at home with or without telemedicine (not new exacerbations); or patient’s express request.

Study variables

The main variable was time until first exacerbation post-discharge at home (with “COPD exacerbation” being defined as acute and sustained deterioration in the patient’s clinical condition, which is greater than the daily fluctuation and requires a change in his/her usual medication) [Citation5,Citation6].

The secondary variables analyzed were: use of healthcare resources, measured as number of home visits by healthcare staff (scheduled and non-scheduled); mean time of home hospitalization; exacerbations occurring post-discharge and re-admissions for this reason. Other secondary variables were: 1) degree of satisfaction with home care (Satisfad10 questionnaire) [Citation21] and, for the intervention group, an additional specific survey consisting of four questions with responses rated on a five-point Likert scale (from 1 through 5, from least to greatest satisfaction and/or need of help), plus a fifth open-ended question on their experience with the monitor (); 2) measurement of anxiety and depression with the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) (trait-tendency) [Citation22,Citation23] in the home hospitalization stage; 3) impact on wellbeing and quality of life, as measured by the COPD Assessment Test (CAT) [Citation24,Citation25]; 4) therapeutic compliance at commencement and at the sixth month, rated by the Morisky-Green-Levine questionnaire [Citation26]; and, in addition for the intervention group, adherence to telemonitoring as shown by fulfillment of the protocolized data transmissions.

Interventions compared

The first stage of the study was home hospitalization (with or without telemonitoring, depending on the group to which the participant was allocated), and the second stage was follow-up after medical discharge (identical for both groups, without telemonitoring), with medical visits at one and 6 months. At these visits, ambulatory and/or hospital exacerbations, and other study variables were recorded (see ).

Control group (conventional home hospitalization)

* Visiting schedule: a first visit was made at the hospital (by the physician and nurse designated to conduct the follow-up), with an evaluation that covered clinical aspects as well as the handling and management of bronchodilators. This was followed by daily home visits, initially carried out exclusively by nursing staff, except for the final visit at which the nurse was accompanied by the physician, in order to give the patient his/her discharge, provided that the latter met the following criteria:

clinical stability, with recovery of daily activities and dyspnea similar to baseline;

saturation levels of >90% with or without oxygen, without the need for rescue medication after initiation of long-acting bronchodilation;and,

correct use of the medication.

Healthcare was available from 8:00 to 15:00 Monday through Friday: if any patient experienced a worsening of his/her condition outside these hours, he/she had to notify the emergency services.

The activities carried out during home visits were intended to ensure consolidation of the patients’ clinical improvement, and train patients and their carers in a “friendlier” environment.

These activities included measurement of vital constants, physical examination, clinical evaluation, and health education (covering information on patients’ own disease, inhalatory techniques, therapeutic compliance, respiratory exercises, nutritional advice, and smoking cessation, if required).

Intervention group (home hospitalization with telemedicine)

* Home visiting schedule: This consisted of: 1) an initial visit made at the hospital (by both physician and nurse); 2) an intermediate visit made by nursing staff, usually one day later, except for patient needs or weekends; and, 3) a final visit on discharge, made by the nurse and the physician. Nursing activities carried out during the visits, office hours, and discharge criteria were identical to those described for the control group.

The first day that the patient was at home, he/she received a visit from the technician, who installed the telemonitoring equipment and instructed both the patient and family members on how to operate it (leaving a contact telephone number for technical support).

* Telemonitoring: this was performed using a multiparametric recording unit, which was fitted with a GSM communication capability and uploaded the patient’s health data to an online web platform (with a lag of approximately 15–30 min), where the data were then reviewed and analyzed by the physician in charge.

The parameters recorded were ECG (leads I, II and III), O2 saturation (%), heart rate, blood pressure, temperature, and respiratory rate.

Patients transmitted their data twice per day (morning and afternoon), at approximately the same time (work days), for this reason the telematic assistance was prolonged from 8 a.m. until 8 p.m on weekdays. The patients would receive a telephone call from the physician to evaluate their clinical situation (symptoms, degree of dyspnea (mMRC), change in appearance and amount of sputum, therapeutic compliance, and complications) and decide on what action was to be taken.

Patients were able to make data transmissions outside of the protocol, on perceiving clinical deterioration or for greater ease of mind.

During the weekend or holidays, the patient could made additional telemonitoring transmissions, but was advised that they would not be reviewed until Monday morning or the first business day, so if he was unwell he should notify the emergency service.

Normality thresholds/intervals were set for the parameters mentioned: in the event of any value being recorded outside these ranges, an alert was generated in the form of an SMS text message sent to the physician’s telephone (). If intervention was required, the patient was contacted and the plan of action explained to him/her (home visit, use of emergency services, change of medication, etc.).

Table 1. Thresholds of the predetermined parameters.

Statistical analysis

The principal hypothesis was to ascertain that after early discharge, health outcomes yielded by experimental treatment (intervention) were no inferior to those yielded by the reference treatment (control). The scientific literature shows that the median “exacerbation-free time” of the reference treatment is 2 months [Citation27], and the “non-inferiority” condition thus requires that the median in the experimental group be similar. It is considered appropriate to set a “non-inferiority” limit of 0.60 units in multiplicative terms with respect to the reference treatment. In other words, we sought to demonstrate that, at minimum, the experimental treatment provides a median exacerbation-free time of no less than 1.2 months (36 days), with the study being deemed to be inferior if exacerbation should occur before this deadline. Hence, to ensure a power of 80% and a significance level of 5%, we calculated that a minimum sample of 58 patients would be required per treatment group (116 in all).

Exacerbation-free time was defined as the interval between home discharge and moment of exacerbation, until termination of the study in cases where this did not occur, or, in the event of loss to follow-up, until the last time recorded.

All analyses were performed according to the intention-to-treat principle.

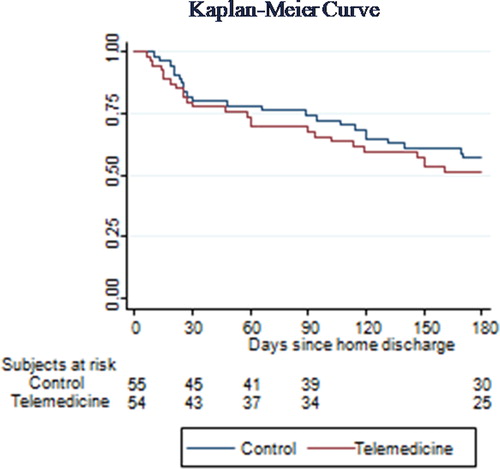

Statistical analysis of the main variable was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test.

Comparisons between groups were performed using the Student-t test for continuous variables, and the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test where the data did not follow a normal distribution.

The statistical software package used was Stata V.15.1.

Results

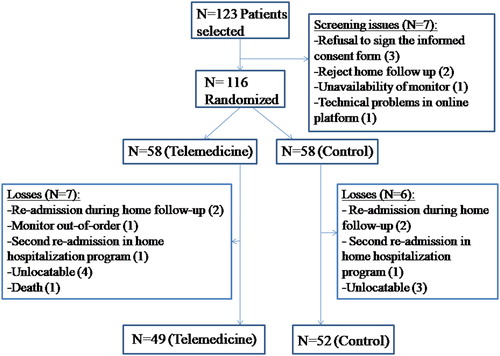

A total of 123 patients were selected, and 116 were randomized, 58 to the telemedicine group (50%) and 58 to the control group (50%); of these, 101 completed the protocolized follow-up ().The recruitment period was March 2012 through January 2018, with follow-up at 6 months ending in July 2018.

No significant differences were found between the two groups in terms of demographic and baseline characteristics (), or in the number of days of hospital admission prior to inclusion in the study, with a mean of 3.4 +/- 1.4 in the telemedicine group and 3.5 +/- 1.5 in the control group (p = 0.704).

Table 2. Demographic and baseline characteristics.

In the case of the main variable, time until first exacerbation, no significant differences were observed between groups, with a median of 48 days (p25-p75:23-120) in the control group and 47 days (p25-p75:19-102) in the intervention group, p = 0.52) (). In the follow-up stage, 23 (41.8%) patients in the control group and 25 (46.3%) in the intervention group experienced exacerbation. In the control group, there was a median of 2 (1-3) exacerbations and there were 13 (23%) severe cases that required admission; in the intervention group, there was a median of 1 (1-2) exacerbation and there were 12 (22%) severe exacerbations.

The duration of the home hospitalization was similar in the two groups with a median of 7 days, and the number of home visits was lower in the intervention group, with the difference being statistically significant ().

Table 3. Number of home visits and length of home hospitalization.

During the home hospitalization stage, 4 patients (2 from each group) required re-admission to hospital for different reasons, namely:

telemedicine group: one due to exacerbated respiratory failure, and another due to rapid atrial fibrillation;

control group: one due to poor control of pain secondary to vertebral compression fractures, and another due to necrotizing pneumonia.

There was only one death across the study, which took place during the post-discharge follow-up stage and was due to a polytraumatism unrelated with the study.

There were no significant differences in satisfaction with homecare services, anxiety-depression and therapeutic adherence, however about the impact on quality of life with the questionnaire CAT there were significant differences ().

Table 4. Questionnaires.

The results of the telemonitoring satisfaction survey (n = 55) are shown in , along with some of the patients’ most repeated answers to the open-ended question about satisfaction/experience with the monitor in . There was an average of 2.23 ± 0.59 daily telemonitorings per patient across the home hospitalization period. It would include protocol transmissions (twice a day) and out-of-protocol; above 100% in almost all cases [mean 111.5% (82%- 141%)] ().

Table 5. Telemonitoring satisfaction survey.

Table 6. Open-ended question about satisfaction/experience with the monitor.

During the weekends or holidays without telematic assistance no more alerts or visits to emergency services were observed.

There was no dropout during the study in any group.

The economic analysis of the study (see ) shows a total cost per telemonitored patient of 362.60€ compared to 364.30€ in the control group. The specific resources in the telemonitored group include: costs of telemonitoring transmission and use of the monitoring device; costs of training the patient in the use of the monitoring device (training visit); and the on-line patient follow-up sessions carried out by the physician; the cost associated with specific telemonitoring resources amounts to 63.28€ per patient. For both groups, the individual cost of the visits is similar (nurse visits and physician-nurse visits); the difference between both groups is due to the lower number of visits carried out for the telemonitored group with respect to the control group. The additional cost generated by the visits in the control group is 64.98 € per patient. The difference in costs between the telemonitoring and control groups amounts to 1.74€ in favor of the control group.

Table 7. Cost per patient: telemedicine and control groups.

Discussion

The TELEMEDCOPD study observed that follow-up with telemedicine makes it possible to reduce the number of healthcare staff visits, without any negative effects in terms of time until first exacerbation.

Although it is true that the close monitoring to which the intervention group was subjected might in part substitute for the lower number of visits, we do not feel that it offset the efficiency obtained because it entailed no travel on the physician’s part, and in the event of some urgent action being required in either group outside the normal office hours of the home hospitalization program, the patient was referred to the emergency services. Moreover, no protocolized data transmissions or calls were made on the weekend, with patients being notified that, in the event of any such data transmission being made, it would be reviewed on the first working day, so that no additional intervention was made with respect to the control group, in which weekend visits were likewise suspended.

In the most recent systematic review by Clemens Kruse in 2019 [Citation15], 13 of the 29 (45%) selected studies pronounced in favor of the greater effectiveness of telemedicine, while 11 of the 29 (38%) found no improvement. They identified a series of favorable results, including a decrease in the number of home visits (as in our study) and improvement in disease management and carer support, as well as a number of drawbacks, ranging from low data quality to an increase in staff workload and costs.

In their studies, Segrelles et al. [Citation28] and Esteban et al. [Citation29] monitored patients with stable COPD for early detection of exacerbations, and reported a decrease in use of health resources, number of hospitalizations, and visits to emergency services. Similarly, the Cochrane review by McLean [Citation17] detected a trend in favor of telemedicine, in the form of a decrease in the number of hospitalizations and visit to emergencies but with no evidence of improvement in quality of life (using the Saint George Respiratory Questionnarie/SGRQ) or in mortality. Our study did not show a decrease in the number of exacerbations or hospitalizations: we feel that this may be related to the close follow-up and educational reinforcement implemented during home hospitalization in both groups, which -as in other studies- would seem to account for the beneficial effect of telemedicine being canceled out [Citation15,Citation16,Citation29–32].

Then again, whereas the mean number of days of admission due to COPD exacerbation is 10.9 according to European Lung Foundation data [Citation33] and 9 according to AudiPOC [Citation34], in our study the mean time of hospital admission was 4 days, which, added to a low re-admission rate in the home hospitalization stage (3.4%), amounts to a cost-effective improvement per se.

Despite receiving fewer visits, the patients followed-up with telemonitoring felt equally well cared for, as was highlighted when satisfaction with home care was measured (SATISFAD-10). In the surveys that we conducted a posteriori, the majority of patients expressed a subjective feeling of safety and security with the telemonitoring service, mentioned its ease of use, and stressed their willingness to use it again on future occasions. Although most patients had an informal carer at home, few needed help to carry out telemonitoring. There was very high adherence in terms of compliance with the two daily data transmissions, with some even making extra transmissions for greater ease of mind. Probably the ones with the fewest data transmissions are those that had weekends through the hospitalization period. However, it should be noted that the follow-up by the medical staff was daily and any failure to send parameters involved a home call.

Acceptance of these new technologies by patients was thus very high and satisfactory, as has already been seen in other studies [Citation17,Citation35,Citation36].

There were no differences between the groups with respect to anxiety-depression measured with the STAI. This coincides with what has been observed by other authors, albeit using other questionnaires (the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale) [Citation32,Citation37,Citation38].

Similarly, there were no differences in adherence to medical treatment, with this improving as follow-up progressed (>80% in both groups on termination of the study), possibly linked to the close follow-up and health education carried out in both groups.

Surprisingly, the quality of life measured initially with CAT, shows significant differences between both groups; being a randomized clinical trial, no differences should have occurred. Likewise, starting from a higher initial CAT, even though the median equals one month, a difference is found between the initial CAT and the one, one month after. We believe that the difference may be due to a little sample size. In other studies, there were no differences in the quality of the life, although they used others questionnaires (SGRQ or SF-36v2) [Citation32,Citation39,Citation40].

The cost difference between the telemonitored group and the control group is minimal and its validity is subject to subtle variations in data transmission costs, the duration of on-line patient follow-up or the costs associated with the use of monitoring devices. However, beyond the cost comparison of both actions, it must be borne in mind that the intervention of telemonitoring generates an additional advantage related to the optimization in the use of health resources. Assuming that 100% of the capacity of the hospital's pneumology service to make home visits is 5.1 visits per patient, in home hospitalization for early discharge, the fact that the number of visits required to effectively attend to a telemonitored patient is 3.8 visits, has as consequence that the capacity of the service for home hospitalization for early discharge could be improved by up to 25.5%. As a consequence, the number of telemonitored patients could be increased by using the same amount of resources, that is, the efficiency of use of health resources is improved while maintaining a similar quality of care.

Limitations

The fact that this was a randomized non-pharmacological intervention study meant that blinding could not be maintained after randomization.

A possible selection bias would lie in the fact that the patients included must be assumed to have different aptitudes for handling new technologies (telemedicine monitor) or adequate family support in this respect, and that the population sample was limited to patients admitted to the Puerta de Hierro Hospital Pneumology Department, thereby excluding Internal Medicine patients who might have a different clinical profile (more pluri-pathological or older). Both the above would amount to a limitation for generalization of results.

There was a prolonged recruitment period, due to the closure of the home hospitalization program during the summer months and to the limited inclusion criteria.

Conclusions

The results of the TELEMEDCOPD study suggest that telemonitoring-based follow-up with medical and nursing supervision, in the early discharge of patients with COPD exacerbation, is as effective as conventional home follow up, being the cost of either strategy not significantly different. Although the telemonitoring procedure shows a slight advantage in relation to costs, the greatest benefit is the evident optimization of the use of care resources. The telemonitored procedure increases the capacity to attend patients in home hospitalization for early discharge while maintaining the same quality of care.

However, more studies are required to allow for recommendations to be drawn up regarding the use of telemonitoring in patients with COPD, defining the patient profile that could benefit best, the optimal point in time (stable phase or exacerbation), and the protocol governing the biomedical parameters (vital constants and clinical symptoms) and form of monitoring (daily, weekly, etc.) that would be needed.

Acknowledgments

We should like to thank the following: Ms. Ana Royuela and Mr. Borja Fernandez of the Biostatistics Department of the Puerta de Hierro Hospital, who collaborated in the statistical analysis: and **RGB Medical Devices, S.A. for the loan of SAFE multiparametric monitoring equipment.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ministerio de Sanidad y Política Social. Estrategia en EPOC del Sistema Nacional de Salud. Ministry of Health and Social Policy. COPD Strategy of the National Health System. Spain. Madrid; 2009.

- World Health Organization: World Health Statistics. 2008. Geneva: World Health Organization 2008–2010. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43890.

- GBD 2015 Chronic Respiratory Disease Collaborators. Global, regional, and national deaths, prevalence, disability-adjusted life years, and years lived with disability for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5(9):691–706. DOI:10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30293-X

- Soriano JB, Alfageme I, Miravitlles M, et al. Prevalence and Determinants of COPD in Spain: EPISCAN II. Arch Bronconeumol. 2020. DOI:10.1016/j.arbres.2020.07.024

- Miravitlles M, Ferrer M, Pont A, et al. Effect of exacerbations on quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a 2 year follow-up study. Thorax. 2004;59(5):387–395. DOI:10.1136/thx.2003.008730

- Wedzicha JA, Singh R, Mackay AJ. Acute COPD exacerbations. Clin Chest Med. 2014;35(1):157–163. DOI:10.1016/j.ccm.2013.11.001

- Donaldson GC, Seemungal TA, Bhowmik A, et al. Wedzicha JA, Relationship between exacerbation frequency and lung function decline in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2002;57(10):847–852. DOI:10.1136/thorax.57.10.847

- Garcia-Aymerich J, Serra Pons I, Mannino DM, et al. Lung function impairment, COPD hospitalisations and subsequent mortality. Thorax. 2011;66(7):585–590. DOI:10.1136/thx.2010.152876

- Soler-Cataluna JJ, Martinez-Garcia MA, Roman Sanchez P, et al. Severe acute exacerbations and mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2005;60(11):925–931. DOI:10.1136/thx.2005.040527

- Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. Unidad de Evaluación de Tecnologías Sanitarias de la Agencia Laín Entralgo. Guía de Práctica Clínica para el tratamiento de pacientes con Enfermedad Pulmonar Obstructiva Crónica (EPOC) [Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality. Health Technology Assessment Unit of the Laín Entralgo Agency. Clinical Practice Guideline for the treatment of patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)]; 2012: UETS N° 2011/6. Spain.

- Marrades RM. Hospital-at-home, a new healthcare approach? Arch Bronchoneumol. 2001;37(4):157–159. DOI:10.1016/S0300-2896(01)75043-0

- British Thoracic Society Development Group. Intermediate care – hospital-at-home in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: British Thoracic Society guideline. Thorax. 2007;62(3):200–210.

- Hernández C, Casas A, Escarrabill J, CHRONIC project, et al. Home hospitalisation of exacerbated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Eur Respir J. 2003;21(1):58–67. DOI:10.1183/09031936.03.00015603

- Sala E, Alegre L, Carrera M, et al. Supported discharge shortens hospital stay in patients hospitalized because of an exacerbation of COPD. EurRespir J. 2001; 17(6):1138–1142. DOI:10.1183/09031936.01.00068201

- Kruse C, Pesek B, Anderson M, et al. Telemonitoring to manage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: systematic literature review. JMIR Med Inform. 2019;7(1):e11496. 20 DOI:10.2196/11496

- Vitacca M, Montini A, Comini L. How will telemedicine change clinical practice in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Ther Adv Respir. 2018; Jan-Dec 121–126. DOI:10.1177/1753465818754778

- McLean S, Nurmatov U, Liu JLY, et al. A. Telehealthcare for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Cochrane Review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2012; Nov62(604):e739–e749. DOI:10.3399/bjgp12X658269

- Jeppesen E, Brurberg KG, Vist GE, et al. Hospital at home for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;16(5):CD003573. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD003573.pub2

- Gonçalves-Bradley DC, Iliffe S, Doll HA, et al. Early discharge hospital at home. CochraneDatabaseSystRev. 2017;6(6):CD000356. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD000356.pub4

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease: Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2019–2020. https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/GOLD-2020-FINAL-ver1.2-03Dec19_WMV.pdf.

- Morales Asencio JM, Bonill de las Nieves C, Celdrán Mañas M, et al. [Design and validation of a home care satisfaction questionnaire: SATISFAD]. Gac Sanit. 2007;21(2):106–113. DOI:10.1157/13101036

- Roberts KE, Hart TA, Eastwood JD. Factor structure and validity of the state-trait inventory for cognitive and somatic anxiety. Psychol Assess. 2016; Feb28(2):134–146. DOI:10.1037/pas0000155

- Perpiña-Galvan J, Richart-Martinez M, Cabañero-Martinez MJ. Reliability and validity of a short version of the STAI anxiety measurement scale in respiratory patients. Arch Bronconeum. 2011; 47(4):184–189. DOI:10.1016/S1579-2129(11)70044-1

- Tsiligianni I, Van der Molen T, Moraitaki D, et al. Assessing health status in COPD. A head-to-head comparison between the COPD assessment test (CAT) and the clinical COPD questionnaire (CCQ). BMC PulmMed. 2012;12(20):1–9. DOI:10.1186/1471-2466-12-20

- Jones PW, Harding G, Berry P, et al. Development and first validation of the COPD assessment test. Eur Respir J. 2009; 34(3):648–654. DOI:10.1183/09031936.00102509

- Nogués Solan X, Sordi Redó ML, Villar García J. Instrumentos de medida de adherencia al tratamiento [Instruments for measuring adherence to treatment. An. Med. Interna. 2007; 24(3):138–141. Spain.

- Hurst JR, Donaldson GC, Quint JK, et al. Temporal clustering of exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009; Mar 1179(5):369–374. DOI:10.1164/rccm.200807-1067OC

- Segrelles Calvo G, Gomez-Suarez C, Soriano JB, et al. A home telehealth program for patients with severe COPD: the PROMETE study. RespirMed. 2014; 108(3):453–462. DOI:10.1016/j.rmed.2013.12.003

- Esteban C, Moraza J, Iriberri M, et al. Outcomes of a telemonitoring-based program (telEPOC) in frequently hospitalizad COPD patients. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;24(11):2919–2930.

- Pedone C, Lelli D. Systematic review of telemonitoring in COPD: an update. Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 2015;83(6):476–484. DOI:10.5603/PiAP.2015.0077

- Schou L, Østergaard B, Rydahl-Hansen S, et al. A randomised trial of telemedicine-based treatment versus conventional hospitalisation in patients with severe COPD and exacerbation - effect on self-reported outcome. J Telemed Telecare. 2013;19(3):160–165. DOI:10.1177/1357633X13483255

- Pinnock H, Hanley J, McCloughan L, et al. Effectiveness of telemonitoring integrated into existing clinical services on hospital admission for exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: researcher of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: researcher blind, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2013; 347(17):f6070. DOI:10.1136/bmj.f6070

- European Lung Foundation Web. URL: http://www.europeanlung.org/es/.

- Pozo-Rodríguez F, López-Campos JL, Alvarez-Martínez CJ, on behalf of the AUDIPOC Study Group, et al. AUDIPOC Study Group. Clinical audit of COPD patients requiring hospital admissions in Spain: AUDIPOC study. Plos One. 2012;7(7):e42156. ; DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0042156

- Mair FS, Wilkinson M, Bonnar SA, et al. The role of telecare in the management of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the home. J Telemed Telecare. 1999;5(1_suppl):66–67. DOI:10.1258/1357633991932603

- Soriano JB, García-Río F, Vázquez-Espinosa E, et al. A multicentre, randomized controlled trial of telehealth for the management of COPD. Respir Med. 2018;144:74–81. DOI:10.1016/j.rmed.2018.10.008

- Vianello A, Fusello M, Gubian L, et al. Home Telemonitoring for patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Pulm Med. 2016;16(1):157 DOI:10.1186/s12890-016-0321-2

- Casas A, Troosters J, Aymerich-García J, members of the CHRONIC Project, et al. Integrated care prevents hospitalisations for exacerbations in COPD patients. Eur Respir J. 2006;28(1):123–130. DOI:10.1183/09031936.06.00063205

- Lewis K, Annandale JA, Warm DL, et al. Home telemonitoring and quality of life in stable, optimised chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Telemed Telecare. 2010;16(5):253–259. DOI:10.1258/jtt.2009.090907

- Gregersen L, Green A, Frausing E, et al. Do telemedical interventions improve quality of life in patients with COPD? A systematic review. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:809–822. DOI:10.2147/COPD.S96079