Abstract

Breathlessness is one of the most frequent symptoms in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). COPD may result in disability, decreased productivity and increased healthcare costs. The presence of comorbidities increases healthcare utilization. However, the impact of breathlessness burden on healthcare utilization and daily activities is unclear. This study’s goal was to analyze the impact of breathlessness burden on healthcare and societal costs. In this observational single-center study, patients with COPD were followed-up for 24 months after completion of a comprehensive pulmonary rehabilitation program. Every three months participants completed a cost questionnaire, covering healthcare utilization and impact on daily activities. The results were compared between participants with low (modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) grade <2; LBB) and high baseline breathlessness burden (mMRC grade ≥2; HBB). Healthcare costs in year 1 were €7302 (95% confidence interval €6476–€8258) for participants with LBB and €10,738 (€9141–€12,708) for participants with HBB. In year 2, costs were €8830 (€7372-€10,562) and €14,933 (€12,041–€18,520), respectively. Main cost drivers were hospitalizations, contact with other healthcare professionals and rehabilitation. Costs outside the healthcare sector in year 1 were €682 (€520–€900) for participants with LBB and €1520 (€1210–€1947) for participants with HBB. In year 2, costs were €829 (€662–€1046) and €1457 (€1126–€1821) respectively. HBB in patients with COPD is associated with higher healthcare and societal costs, which increases over time. This study highlights the relevance of reducing costs with adequate breathlessness relief. When conventional approaches fail to improve breathlessness, a personalized holistic approach is warranted.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a chronic disease that is characterized by persistent reduction of airflow and respiratory symptoms [Citation1]. The worldwide prevalence of COPD was estimated at 3.9% in 2017 [Citation2] and annually about three million people die because of COPD [Citation3]. The prevalence of COPD is expected to increase globally in the coming years due to higher smoking prevalence in low-income countries and ageing of the population [Citation4].

The most frequently reported symptoms of COPD are breathlessness, coughing and fatigue [Citation5]. Disease severity is determined using the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) classification [Citation1]. Within this classification, the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) scale [Citation6] and COPD Assessment Test (CAT) [Citation7,Citation8] are used to measure symptom burden. Low breathlessness burden is represented by a mMRC grade of 0 or 1 point and high breathlessness burden by a mMRC grade of ≥2 points; low health status is represented by a CAT score of <10 points and high health status by a CAT score of ≥10 points [Citation1].

COPD may result in disability, decreased productivity and increased health-related costs [Citation1]. In COPD, exacerbations and hospital admissions account for the largest component of health-related costs [Citation9–11]. With increasing disease severity, healthcare utilization increases [Citation9,Citation11,Citation12]. Furthermore, healthcare costs increase with the presence of comorbidities [Citation9]. Next to the healthcare costs, COPD has a major impact on society [Citation13]. In 2017, COPD was the sixth leading cause of loss in disability-adjusted life years for women and ninth leading cause for men worldwide [Citation14]. With increasing disease severity, there is impact on workplace and home productivity and on the burden for relatives [Citation9,Citation10,Citation13].

Current knowledge on the impact of disease severity and breathlessness burden on healthcare utilization and costs is based on retrospective claims data [Citation9,Citation12] or patient data recalling 12 months [Citation10]. The goal of this study was to prospectively analyze the impact of breathlessness burden in COPD, assessed by the mMRC scale, on societal costs over a follow-up period of 24 months after completion of a comprehensive pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) program.

Methods

Study design

This was a secondary analysis of the CIRO CO-morbidity (CIROCO) study, an observational single-center study to identify biomarkers, co-morbidities, increased healthcare costs and poor prognosis in patients with COPD. The methodology of the CIROCO study has been described in detail elsewhere [Citation15]. For the current analysis, data of the PR program were left aside. The baseline assessment for this analysis was therefore the final assessment of the PR program. Participants were recruited between November 2007 and November 2010. All subjects provided written informed consent. The study was approved by the local medical ethics committee (MEC 10-3-067) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

For the current analysis, a societal perspective was adopted including healthcare costs and costs outside the healthcare sector.

Participants

Patients were eligible to participate in the CIROCO study if they were diagnosed with moderate to very severe COPD (GOLD grades II–IV), smoked at least 10 pack-years and were aged between 40 and 80 years. For the current analysis, participants had to have completed an 8-week inpatient (5 days/week) or 14-week outpatient (3 days/week) comprehensive PR program at CIRO in Horn, The Netherlands and at least one visit during the follow-up. Exclusion criteria were described in detail elsewhere [Citation15].

Assessments and questionnaires

Baseline measurements

At baseline, participants underwent a two-day assessment at the end of the PR program, during which data was collected on demographics, smoking status, number of exacerbations and hospital admissions in the past 12 months, lung function, comorbidities using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) [Citation16] and mMRC grade [Citation6].

Follow-up

During a follow-up of 24 months, participants completed the mMRC breathlessness scale and a cost questionnaire (supplementary material 1) every three months during a phone call. The mMRC breathlessness scale assesses the perceived disability of breathlessness in activities of daily living. The scale consists of five grades (grade 0: breathless only with strenuous exercise; grade 4: too breathless to leave the house or breathless when dressing) [Citation6]. The cost questionnaire covered healthcare utilization, employment status at baseline, inability to perform daily activities (employed and/or household work of both participants and informal caregivers), and long-term sick leave. Healthcare utilization included contact with healthcare professionals, hospitalization, respiratory tests, and use of long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT). For all questions, the reason (breathing problems or other health problems) and number of times or number of days were collected. Furthermore, prescribed and over-the-counter medication use was discussed. At the end of the follow-up, information on participation in a second PR program was collected from the patient file and prescribed medication use was checked using medication lists.

To be able to calculate healthcare costs, several assumptions about exacerbations and hospital admissions, medication use and use of LTOT were made. These are described in supplementary material 2.

Healthcare costs

For valuation of healthcare resource use, reference prices were obtained from the cost manual of the Dutch National Healthcare Institute [Citation17] and indexed to July 2019. For the reference prices not stated in the cost manual, the rate list first-line diagnostics of the Dutch Healthcare Authority [Citation18] was used. Prescribed medication was valued using medication prices of July 2019 from the medication database by the Dutch National Healthcare Institute [Citation19]. Prices of medication that were not on the market anymore were extracted from the Farmacotherapeutisch Kompas 2008 and indexed to July 2019. Delivery costs by the pharmacist were accounted for medication within the drug reimbursement system. For the base-case analysis, the lowest medication price was used [Citation17]. A sensitivity analysis using the highest medication price was conducted.

Costs outside healthcare sector

Information on employment status was only collected at baseline of the CIROCO study. Data collection regarding impact on daily activities did not distinguish between household activities or paid work. Therefore, in the base-case analysis impact on daily activities for both participants and informal caregivers was conservatively valued as household work. In a sensitivity analysis, impact on daily activities for the subgroup of participants that were employed at baseline was valued using the friction cost method [Citation17]. Impact on daily activities for the other participants was still valued as household work. In another sensitivity analysis, impact on daily activities of informal caregivers was excluded from the analysis. Over-the-counter medication was valued using medication prices of July 2019 from the medication database by the Dutch National Healthcare Institute [Citation19]. Data on transportation to healthcare professionals or the hospital were not collected. Based on the mean distance to healthcare professionals or the hospital, transportation by car and reference prices from the cost manual [Citation17], costs for transportation were calculated.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed using SPSS statistics version 25.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Participant characteristics, healthcare utilization and impact on daily activities were described as mean (SD) for continuous variables and number (percentage) for categorical variables. Cost data of the first and second year were presented as mean (95% bootstrapped bias-corrected and accelerated confidence interval; 95% BCa CI). Cost data for the second year were discounted with 4%, according to the Dutch cost manual. Comparison between the years was performed using Wilcoxon signed rank tests.

Baseline mMRC grades were used to compose two breathlessness burden profiles. Participants with low breathlessness burden reported a mMRC grade of <2 points at start of the follow-up and participants with high breathlessness burden reported a mMRC grade of ≥2 points at start of the follow-up, according to the GOLD classification [Citation20]. Differences in baseline characteristics, healthcare utilization or impact on daily activities between the groups with low and high breathlessness burden were analyzed using independent samples T-tests or Mann-Whitney U tests, according to data distribution. Differences in healthcare utilization or impact on daily activities within breathlessness burden groups between breathing and other health problems were analyzed using dependent samples T-tests or Wilcoxon signed rank tests, according to data distribution. Categorical data were analyzed using a χ2 tests. Correlation between continuous parameters was analyzed using Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficient, according to data distribution. Missing data were imputed using single imputation on means because of the minimal amount of missing data.

Results

Participants

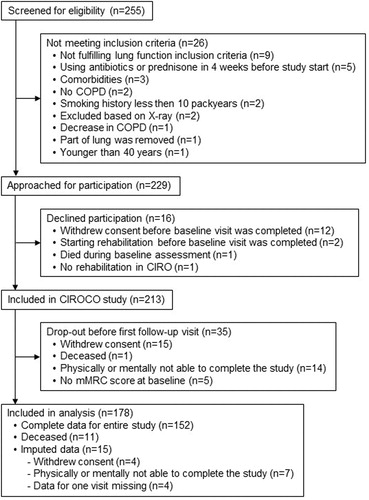

Of the 213 participants included in the CIROCO study, data of 178 was included in the current analysis (). A total of 350 patient years was collected, 2.0 (0.2) years per participant. The total population was aged 63.6 (7.0) years and 60.1% was male.

Participants not included in the analysis withdrew consent, deceased, dropped-out because of physical or mental inability to complete the study before the first follow-up visit or missed an mMRC grade at baseline (). Participants not included in the analysis were comparable to participants included in the analysis, except for smoking status: participants not included were more often smoker (44.1% vs. 19.1%; p = 0.002).

Breathlessness burden

Before the PR program, 59 participants (33.1%) experienced low breathlessness burden and 119 (66.9%) experienced high breathlessness burden. During PR, in 10 participants breathlessness burden changed from low to high breathlessness burden and in 33 participants from high to low breathlessness burden. After the PR program, so at baseline of these analyses, 82 participants (46.1%) experienced low breathlessness burden and 96 participants (53.9%) experienced high breathlessness burden. Participants with low and high breathlessness burden were similar at baseline, except for number of exacerbations in the previous 12 months, CCI and FEV1 (). Breathlessness burden during follow-up is shown in supplementary material 3 .

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of total study population and participants with low and high breathlessness burden.

Employment status

Ten participants (5.6%) were employed full-time at baseline (seven with low breathlessness burden and three with high breathlessness burden) and were working 39.9 (6.8) hours/week. Eight participants (4.5%) were employed part-time (seven with low breathlessness burden and one with high breathlessness burden) and were working 25.8 (5.4) hours/week. Another four participants (2.2%) were employed, but the amount of hours is unknown. 26 participants (14.6%) were on long-term sick leave for a period of 7.5 (7.8) months. Reasons for long-term sick leave were breathing problems (50.0%), other health problems (15.4%), breathing and other health problems (3.8%) or unknown (30.8%). 14 participants (7.9%) were incapacitated for work. The other participants were retired (87, 48.9%), house-person (25, 14.0%) or unemployed (4, 2.2%).

Healthcare costs

Outpatient care

During the follow-up, all participants visited a healthcare professional for breathing problems as well as other health problems. The family doctor and medical specialist were visited more often by participants with high breathlessness burden compared to participants with low breathlessness burden (p = 0.015 and p = 0.042, respectively), while other healthcare professionals (including, but not limited to physiotherapists, occupational therapists, and nurses) were visited equally often (p = 0.152; ). In the majority of cases, visits were more often for breathing problems than for other health problems ().

Table 2. Healthcare and non-healthcare utilization per participant per year.

In the first year, costs for outpatient care for participants with low breathlessness burden were €3527 and for participants with high breathlessness burden €3792. In the second year, these costs were €3634 and €4166, respectively. Costs did not differ between groups ( and supplementary material 3 ) or years ().

Table 3. Mean costs per participant per year (in Euro’s).

Inpatient care

Participants with high breathlessness burden more often needed inpatient care compared to participants with low breathlessness burden (71.9% vs. 57.3%; p = 0.042). Especially, participants with high breathlessness burden more often visited the emergency room or were more often hospitalized compared to participants with low breathlessness burden (p = 0.016 and p = 0.005, respectively; ). In the majority of cases, contacts were more often for breathing problems than for other health problems ().

In the first year, costs for inpatient care were €1606 for participants with low breathlessness burden and €3934 for patients with high breathlessness burden. In the second year, these costs were €1876 and €3910, respectively. Costs for participants with high breathlessness burden were higher in both years ( and supplementary material 3 ). Costs did not differ between the years ().

Diagnostics

The number of participants that underwent a respiratory test (including spirometry test, advanced pulmonary test, plain chest X-ray, and chest computer tomography) and the number of tests were similar for participants with low and high breathlessness burden (p = 0.619 and p = 0.199, respectively; ). Costs for pulmonary tests were similar for participants with low and high breathlessness burden in the first year (€191 and €240 per participant, respectively) and second year (€274 vs. €311 per participant, respectively; and supplementary material 3 ).

Pulmonary rehabilitation

Within the two years, 30 participants were again admitted to the assessment prior to a comprehensive PR program. In the first year, 1/82 (1.2%) participants with low breathlessness burden and 5/96 (5.2%) participants with high breathlessness burden were re-admitted (p = 0.142). In the second year, 5/82 (6.1%) participants with low breathlessness burden and 19/96 (19.8%) participants with high breathlessness burden were re-admitted (p = 0.008). In total, nine participants only completed the baseline assessment and 21 participants started the PR program (five with low breathlessness burden and 16 with high breathlessness burden). Costs for PR were €12,977 per participant for the first year and €20,383 per participant for the second year, only taking into account the participants who attended PR. Per year, costs for participants with low or high breathlessness burden were not different ( and supplementary material 3 ). Rehabilitation costs for patients with high breathlessness burden were higher in the second year compared to the first year (p = 0.008; ).

Prescribed medication

A total of 5291 medication prescriptions within the drug reimbursement system were registered, 2890 for respiratory disease and 2401 for other diseases. This equals 16.2 prescriptions for respiratory medication and 13.5 prescriptions for other medication per participant (p = 0.056). Participants with high breathlessness burden used significantly more respiratory medication compared to other medication (19.0 vs. 14.1, p = 0.003), which was not the case for participants with low breathlessness burden (13.0 vs. 12.7, p = 0.590; ).

At baseline, 97.2% of participants was treated with a long acting bronchodilator, 86.5% was treated with a short acting bronchodilator, and 91.6% was treated with an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS). The frequency of use of medication for participants with low and high breathlessness burden during the follow-up is presented in . The use of short-acting bronchodilators was higher for participants with high breathlessness burden compared to participants with low breathlessness burden (82.3% vs. 61.0%, p = 0.002). All other types of medication were used equally often by participants with low and high breathlessness burden ().

In the first year, medication costs were €1616 for participants with low breathlessness burden and €1867 for patients with high breathlessness burden (p = 0.008; ). In the second year, these costs were €1772 and €2028, respectively (p = 0.114; ). Costs did not differ between groups ( and supplementary material 3 ).

Long-term oxygen therapy

LTOT was used by 84 participants for on average 26.4 (17.7) weeks per participant per year. 32/82 (39.0%) participants with low breathlessness burden and 52/96 (54.2%) participants with high breathlessness burden used LTOT (p = 0.044; ). Costs per participant were not different for both groups, taking into account only the participants that used LTOT (€566 vs. €629 for the first year and €713 vs. €681 for the second year; and supplementary material 3 ). Costs for participants with high breathlessness burden were higher in the second year compared to the first year (p = 0.020; ).

Costs per subgroup

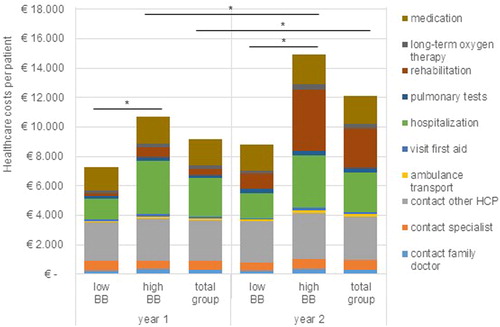

Total healthcare costs in the first year were €9155 per participant and in the second year €12,122 per participant (). In the first year, costs of participants with low breathlessness burden were lower (€7302) compared with participants with high breathlessness burden (€10,738) ( and supplementary material 3 ). Also, in the second year, costs of participants with low breathlessness burden were lower (€8830) than costs of participants with high breathlessness burden (€14,933) ( and supplementary material 3 ). Costs for participants with high breathlessness burden and for the total study population were higher in the second year compared to the first year ( and ).

Figure 2. Healthcare costs per participant per year. BB: breathlessness burden; HCP: healthcare professional. *Significant difference.

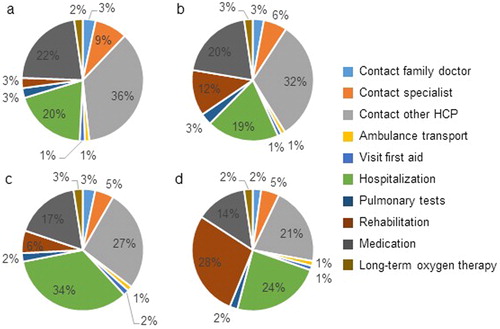

For participants with low breathlessness burden, the largest cost components were contacts with other healthcare professionals (36% in year 1 and 32% in year 2), medication (22% in year 1 and 20% in year 2) and hospitalizations (20% in year 1 and 19% in year 2; ). For participants with high breathlessness burden, the largest cost components differed per year. For year 1, these were hospitalizations (34%), contact with other healthcare professionals (27%) and medication (17%), while for year 2 these were rehabilitation (28%), hospitalization (24%) and contact with other healthcare professionals (21%; ).

Figure 3. Cost components of healthcare resource use. (a) Patients with low breathlessness burden in year 1. (b) Patients with low breathlessness burden in year 2. (c) Patients with high breathlessness burden in year 1. (d) Patients with high breathlessness burden in year 2. HCP: healthcare professional.

Costs outside the healthcare sector

Impact on daily activities

90.2% of participants with low breathlessness burden and 99.0% of participants with high breathlessness burden was unable to perform daily activities during the two years of follow-up (p = 0.008; ). Participants with low breathlessness burden were unable to perform daily activities on 30.0 (42.9) days, while participants with high breathlessness burden were unable to perform daily activities on 75.5 (84.2) days (p < 0.001; ). For participants with low breathlessness burden, the costs were €339 per participant in year 1 and €493 per participant in year 2 (p = 0.485), while for participants with high breathlessness burden the costs were €1153 per participant in year 1 and €963 per participant in year 2 (p = 0.553; and supplementary material 3 ). For both groups, inability was more often due to breathing problems than other health problems ().

18.3% of informal caregivers of participants with low breathlessness burden and 30.2% of informal caregivers of participants with high breathlessness burden had to interrupt their daily activities to take care of the participants (p = 0.066; ). This was on 3.1 and 8.1 days per participant per year, respectively (p = 0.064). Costs were €49 in the first year and €27 in the second year for informal caregivers of participants with low breathlessness burden (p = 0.280) and €23 in the first year and €204 in the second year for informal caregivers of participants with high breathlessness burden (p = 0.001; and supplementary material 3 ).

Over-the-counter medication

A total of 286 over-the-counter medications were registered, 113 for respiratory disease and 173 for other diseases (p = 0.004). The number of medications per participant was equal for participants with low and high breathlessness burden (1.4 vs. 1.8, p = 0.137).

Over-the-counter medication costs per participant were €189 for low breathlessness burden and €242 for high breathlessness burden in the first year and €212 for low breathlessness burden and €181 for high breathlessness burden in the second year ( and supplementary material 3 ). Costs for participants with high breathlessness burden were higher in year 1 compared to year 2 (p = 0.027; ).

Transportation

Annual transportation costs were €101 per participant for low breathlessness burden and €105 per participant for high breathlessness burden. Transportation costs in both groups were not different for the first and second year ( and supplementary material 3 ).

Total societal costs

Total societal costs differed between participants with low and high breathlessness burden in both years ( and supplementary material 3 ). Costs of participants with low breathlessness burden amounted €7985 in the first year and €9660 in the second year, while costs of participants with high breathlessness burden were €12,258 in the first year and €16,390 in the second year. There was no difference between the years ().

Healthcare costs were weakly correlated with FEV1, both for low breathlessness burden (Spearman ρ = 0.103, p = 0.357 for year 1 and Spearman ρ = 0.241, p = 0.029 for year 2) and for high breathlessness burden (Spearman ρ = 0.061, p = 0.555 for year 1 and Spearman ρ = 0.067, p = 0.515 for year 2). For societal costs, the correlations were similar (low breathlessness burden year 1: Spearman ρ = 0.119, p = 0.288; high breathlessness burden year 1: Spearman ρ = 0.080, p = 0.438; low breathlessness burden year 2: Spearman ρ = 0.224, p = 0.043; high breathlessness burden year 2: Spearman ρ = 0.095, p = 0.358).

Sensitivity analysis

and supplementary material 3 show the results of the sensitivity analyses. None of the analyses influenced the total societal costs to such extent that conclusions were altered, in both years costs for participants with high breathlessness burden were higher compared with costs of participants with low breathlessness burden. In the scenario of highest medication prices, the costs for participants with high breathlessness burden were higher in the second year compared to the first year (p = 0.035), while in the other scenarios there was only a trend ().

Table 4. Results of sensitivity analyses on total societal costs per participant per year (in Euro’s).

Furthermore, scenarios with lowest costs and scenarios with highest costs were combined. The scenario with lowest costs equals the scenario in which impact on daily activities of informal caregivers was excluded. The scenario with highest costs included highest medication prices and valuing impact on daily activities of participants based on baseline employment status. Both scenarios had no influence on the differences between the groups, while in the scenario with the highest costs the costs for participants with high breathlessness burden were higher in the second year compared to the first year (p = 0.030; ).

Discussion

The CIROCO study provided an overview of healthcare and non-healthcare resource utilization and costs of patients with COPD who completed a comprehensive PR program during two years. This secondary analysis showed that high breathlessness burden in patients with COPD is associated with high healthcare and non-healthcare costs. Total annual societal costs of participants with low breathlessness burden (mMRC < 2) were €7985 (€7047–€9087) in year 1 and €9660 (€8045–€11,537) in year 2 versus €12,258 (€10,573–€14,321) in year 1 and €16,390 (€13,255–€19,865) in year 2 for participants with high breathlessness burden. The difference between low and high breathlessness burden applied to almost all cost categories, except for outpatient care, diagnostics, and medication.

Hospitalization, medication and contact with other healthcare professionals were the main cost drivers in this study. Previous cost analyses have shown similar results for hospitalization and medication [Citation9–13,Citation21,Citation22]. The large contribution of contact with other healthcare professionals can be explained by the inclusion of participants immediately after completing a PR program. Although not registered, it can be assumed that the vast majority of the reported visits was with the physiotherapist. These patients are encouraged to continue training with a physiotherapist to retain the results of the PR program.

Patients with advanced COPD often have multimorbidity and experience multiple symptoms [Citation23]. The current results show that medical specialists are consulted mainly for breathing problems and these visits are probably more on a scheduled basis, given the results that medical specialists are visited almost equally often by patients with low and high breathlessness burden. Family doctors are consulted for all kinds and more emergent problems, since they are visited almost equally often for breathing and other health problems, but more often by patients with high breathlessness burden than by patients with low breathlessness burden.

Almost as many respiratory tests were performed as visits to the chest physician. Furthermore, standard treatment with long-acting bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids is used by almost all participants. Participants with high breathlessness burden subsequently use short-acting bronchodilators as attempt to minimize symptoms. When these attempts fail, a new PR program is considered, given the results that significantly more patients with high breathlessness burden attend a PR program in the second year compared to the first year. Furthermore, PR programs in the second year are more often inpatient, leading to higher costs. This makes the PR program the largest cost component for this group in the second year.

Breathlessness burden appears not to be a strong predictor of specialist visit frequency, deployed diagnostics or costs of applied pharmacological treatment. However, it can be assumed that this patient group requires another management approach. Given the multifactorial nature of breathlessness, a holistic approach should be considered [Citation24,Citation25]. When patients still experience severe breathlessness burden in daily life after completion of a comprehensive PR program, more focus should be on palliation of their breathlessness. This is emphasized by clinical practice guidelines [Citation26,Citation27]. Opioids have an important place in palliation of refractory breathlessness [Citation28], but results of the current study show that only 4.2% of patients with high breathlessness burden uses opioids for breathing problems. In a Swedish study observing patients with COPD needing LTOT, a similar low prescription rate was shown [Citation29].

Costs outside the healthcare sector only comprised 8.6% of total societal costs for participants with low breathlessness burden and 10.4% for participants with high symptom burden. This is much lower compared to other studies including patients with COPD in general [Citation12,Citation13] or participating in a disease management program [Citation9]. However, compared to these studies the employment rate in our study population at baseline was much lower (12.4% compared to 25.6–67.1%). This is probably due to the population included in our study that is generally older and has more severe COPD.

Indeed, all patients in our study completed a PR program, reflecting that they experienced limitations in their daily life. Still, the amount of days patients were unable to perform daily activities was 2.52 times higher in patients with high breathlessness burden compared to patients with low breathlessness burden. These patients were not able to perform their daily activities, which may have a major impact on their quality of life [Citation30]. When a patient is unable to perform household work, the informal caregiver may take over such activities. This is illustrated by the significant higher number of days informal caregivers of patients with high breathlessness burden were unable to perform daily activities, especially in the second year. This emphasizes the additional burden on informal caregivers accompanied with increased breathlessness burden.

This study has several strengths and limitations. First, this is the first study of prospective patient-reported data in COPD with a follow-up of two years and a short recall period of three months. Second, patients with optimal pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment have been included, since all patients completed a PR program. Third, several sensitivity analyses were performed, confirming that the base-case results were robust.

Some limitations of the study have to be considered. First, the stratification of breathlessness burden was based on the mMRC grade at baseline, while mMRC grade was assessed during each follow-up visit. Patients showed various breathlessness burden profiles, which has been shown in Supplementary material 3. 35.4% of participants showed a variable mMRC grade over time. Second, this study fully relied on patient report and was not underpinned with patient file data, except for rehabilitation and prescribed medication. This means that study results may be influenced by recall bias. However, participants knew they had to report their healthcare utilization every three months and several participants kept notes in these periods. Third, calculation of costs was based on several assumptions. When it was not clear if a contact had taken place for breathing or other health problems, the frequency was equally divided over these components. Over-the-counter medication was only registered if patients mentioned it and is therefore probably not complete. The mode of transportation was not collected and therefore transportation costs were estimated based on transportation by car. Employment status of the participants was reported at baseline of the CIROCO study and had to be extrapolated to baseline of this analysis based on data on long-term sick leave. Employment status of informal caregivers was not known at all. Therefore, valuing of impact on daily activities was done conservatively, using prices for household work. However, the sensitivity analyses showed that valuation based on the baseline employment status did not significantly affect the total societal costs. Fourth, the data used for this analysis were collected between 2008 and 2013. However, reference prices for 2019 were used to value healthcare costs. In the intervening years, treatment guidelines have changed [Citation1]. Fifth, patients included in this study recently completed a PR program and were instructed to continue training with the physiotherapist. Also, patients have been educated in symptom recognition and therefore might contact a family doctor or medical specialist sooner. Therefore, the current results cannot be extrapolated to the general population of patients with COPD. Finally, the CIROCO study included some invasive tests for which patients had to come to CIRO. Therefore, it might be assumed patient for whom this was difficult (due to disease severity or due to employment) declined to participate.

Conclusions

Patients with high breathlessness burden show higher healthcare and societal costs compared to patients with low breathlessness burden and this cost difference increases over time. Breathlessness is a complex symptom, which asks for a personalized holistic approach. Each approach of proactive palliative care that improves breathlessness burden might also influence healthcare-related costs. A recent systematic review showed the effectiveness of holistic breathlessness services on breathlessness, anxiety, depression and costs in patients with cancer [Citation31]. These services included education, psychosocial support, self-management strategies, and other appropriate interventions. Furthermore, these services include the informal caregivers and/or family and the home situation. The management of patients with high breathlessness burden should shift more to these holistic approaches in order to relieve symptoms and decrease the economic burden on society.

Disclosure statement

MvdB reports grants from ZonMW, during the conduct of the study. LEGWV reports grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from GSK, personal fees from Chiesi, personal fees from Menarini, personal fees from Pulmonx, personal fees from AGA Linde, personal fees from Boehringer, personal fees from Zambon, personal fees from Verona Pharma, outside the submitted work. FMEF reports grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees from Chiesi, personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline, grants and personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from TEVA, outside the submitted work. DJAJ reports grants from The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMW), The Hague, The Netherlands (Grant number 836031012), during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees from AstraZeneca, outside the submitted work. The remaining authors have no relevant conflicts to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (2020 report); 2020. Available from: https://goldcopd.org/.

- GBD Chronic Respiratory Disease Collaborators. Prevalence and attributable health burden of chronic respiratory diseases, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(6):585–596. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30105-3

- GBD 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016;388(10053):1459–1544. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1

- Lopez AD, Shibuya K, Rao C, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: current burden and future projections. Eur Respir J. 2006;27(2):397–412. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.06.00025805

- Janssen DJ, Spruit MA, Wouters EF, et al. Daily symptom burden in end-stage chronic organ failure: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2008;22(8):938–948. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216308096906

- Bestall JC, Paul EA, Garrod R, et al. Usefulness of the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 1999;54(7):581–586. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.54.7.581

- Dodd JW, Marns PL, Clark AL, et al. The COPD Assessment Test (CAT): short- and medium-term response to pulmonary rehabilitation. COPD. 2012;9(4):390–394. DOI:https://doi.org/10.3109/15412555.2012.671869

- Jones PW, Harding G, Berry P, et al. Development and first validation of the COPD Assessment Test. Eur Respir J. 2009;34(3):648–654. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00102509

- Kirsch F, Schramm A, Schwarzkopf L, et al. Direct and indirect costs of COPD progression and its comorbidities in a structured disease management program: results from the LQ-DMP study. Respir Res. 2019;20(1):215–215. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-019-1179-7

- Wouters EF. The burden of COPD in The Netherlands: results from the Confronting COPD survey. Respir Med. 2003;97(Suppl C):S51–S59. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0954-6111(03)80025-2

- Dzingina MD, Reilly CC, Bausewein C, et al. Variations in the cost of formal and informal health care for patients with advanced chronic disease and refractory breathlessness: a cross-sectional secondary analysis. Palliat Med. 2017;31(4):369–377. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216317690994

- Stephenson JJ, Wertz D, Gu T, et al. Clinical and economic burden of dyspnea and other COPD symptoms in a managed care setting. COPD. 2017;12:1947–1959. DOI:https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S134618

- van Boven JFM, Vegter S, van der Molen T, et al. COPD in the working age population: the economic impact on both patients and government. COPD. 2013;10(6):629–639. DOI:https://doi.org/10.3109/15412555.2013.813446

- GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018;392(10159):1789–1858. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7

- Vanfleteren LE, Spruit MA, Groenen M, et al. Clusters of comorbidities based on validated objective measurements and systemic inflammation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(7):728–735. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201209-1665OC

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8

- Zorginstituut Nederland. Kostenhandleiding: methodologie van kostenonderzoek en referentieprijzen voor economische evaluaties in de gezondheidszorg. 2015.

- Nederlandse Zorg Autoriteit. Tarievenlijst Eerstelijnsdiagnostiek. 2013.

- Zorginstituut Nederland. Medicijnkosten.nl [cited 2019 Jul 1]. Available at: https://www.medicijnkosten.nl/.

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global Strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2019 Report. 2019.

- Suijkerbuijk AWM, de Wit GAA, Wijga AH, et al. Societal costs of asthma, COPD and respiratory allergy [Maatschappelijke kosten van astma, COPD en respiratoire allergie]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2013;157(46):A6562–A6562.

- Hoogendoorn M, Feenstra TL, Rutten-van Mölken MPMH. Projections of future resource use and the costs of asthma and COPD in the Netherlands [Toekomstprojecties van het zorggebruik en de kosten van astma en COPD in Nederland]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2006;150(22):1243–1250.

- Janssen DJ, Spruit MA, Uszko-Lencer NH, et al. Symptoms, comorbidities, and health care in advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or chronic heart failure. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(6):735–743. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2010.0479

- Rocker G, Horton R, Currow D, et al. Palliation of dyspnoea in advanced COPD: revisiting a role for opioids. Thorax 2009;64(10):910–915. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.2009.116699

- Janssen DJA, Johnson MJ. Palliative treatment of chronic breathlessness syndrome: the need for P5 medicine. Thorax 2020;75(1):2–3. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2019-214008

- Lanken PN, Terry PB, Delisser HM, et al.; ATS End-of-Life Care Task Force. An official American Thoracic Society clinical policy statement: palliative care for patients with respiratory diseases and critical illnesses. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(8):912–927. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200605-587ST

- Marciniuk DD, Goodridge D, Hernandez P, et al.; Canadian Thoracic Society COPD Committee Dyspnea Expert Working Group. Managing dyspnea in patients with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a Canadian Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline. Can Respir J. 2011;18(2):69–78. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/745047

- Ekstrom M, Bajwah S, Bland JM, et al. One evidence base; three stories: do opioids relieve chronic breathlessness? Thorax 2018;73(1):88–90. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-209868

- Ahmadi Z, Bernelid E, Currow DC, et al. Prescription of opioids for breathlessness in end-stage COPD: a national population-based study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:2651–2657. DOI:https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S112484

- Ahmadi Z. The burden of chronic breathlessness across the population. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2018;12(3):214–218. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1097/SPC.0000000000000364

- Brighton LJ, Miller S, Farquhar M, et al. Holistic services for people with advanced disease and chronic breathlessness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax 2019;74(3):270–281. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-211589