Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a chronic progressive lung disease which imposes significant health and economic burdens on societies. Self-management is beneficial in controlling and managing COPD and health literacy (HL) is a major driver of COPD self-management. This review aims to summarize the most recent evidence on the effectiveness of HL driven COPD self-management interventions using randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Eight data bases including Science Citation Index, Academic Search Complete, Social Sciences Citation Index, CINAHL Plus, APA PsycInfo, MEDLINE, Scopus and ScienceDirect were searched to find eligible RCTs assessing the effectiveness of HL interventions on COPD self-management outcomes in outpatient settings between 2008 and February 2020. Ten RCTs met the eligibility criteria. The review found that HL interventions led to moderate improvements in physical activity levels (four out of seven trials) and COPD knowledge (three out of six trials). Surprisingly, none of the RCTs led to significant improvement in medication adherence, which warrants further studies. Furthermore, there were inconclusive findings regarding other COPD self-management outcomes such as smoking cessation, medication adherence, dyspnea, mental health, hospital admissions and health related quality of life.

What is known about the topic?

COPD self-management interventions are effective in improving patients’ health outcomes. Health literacy is a crucial factor to engage patients and to ensure the success of self-management interventions. However, our knowledge about the effectiveness of health literacy driven COPD self-management trials is limited.

What does this review add to literature?

Health literacy driven COPD self-management trials in outpatient settings have a promising results in improving patients’ COPD knowledge and physical activity levels. However, they failed to improve endpoint outcomes such as quality of life and hospitalization rates. Interventions with larger sample size and longer duration of follow-up are more likely to lead better outcomes.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a disease characterized by the progressive airway obstruction and is associated with a significant socioeconomic burden and high morbidity and mortality rates [Citation1,Citation2]. According to the recent global burden of disease study, COPD was the third leading cause of death worldwide in 2017 [Citation3]. In 2016, it was estimated that 251 million people are living with COPD worldwide [Citation4]. Of those, 65 million had a moderate to severe disease [Citation4].

COPD self-management is a key component of COPD management behaviors such as quitting smoking, medications adherence, correct inhaler use, healthy diets and physical activity [Citation5,Citation6]. COPD self-management also equips patients with the required skills to cope with their breathlessness and recognize early symptoms of exacerbation [Citation5,Citation7,Citation8]. The current evidence further suggests that COPD self-management interventions lead to better health related quality of life, reduced hospital admissions and emergency visits and decreased health care costs [Citation9–16].

Health literacy (HL) is a critical factor for the success of COPD self-management [Citation17–19]. World Health Organization (WHO) has defined HL as “cognitive and social skills that determine the motivation and ability of individuals to gain access to understand and use information in ways which promote and maintain good health” [Citation20,Citation21]. Low HL is associated with limited patients’ access to the available supportive services and resources, and limited understanding of the importance of self-management techniques [Citation22–26]. HL is also associated with poor health outcomes such as higher mortality and hospitalization rates [Citation6,Citation27].

Limited theoretical frameworks have been used in the design and interpretation of HL driven interventions’ outcomes [Citation28]. The social ecological framework is the most common theory used to explain the roles and effects of HL on health outcomes. It mainly focused on the importance of the context factors and explained strategies to improve HL using multilevel interventions to address the individual and social factors influencing health outcomes [Citation29]. Another theory was the health belief model which is used to to explain and predict health behaviors, especially access to health care services [Citation28]. However, most of the HL interventions lack a clear theoretical framework [Citation30].

COPD self-management interventions used HL to achieve better patient engagement and health outcomes [Citation31,Citation32]. However, their effectiveness varies across different studies. This systematic review aims to summarize the existing evidence using the most recent randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on the effectiveness of COPD self-management interventions focusing on HL in outpatient settings.

Methods

Search strategy

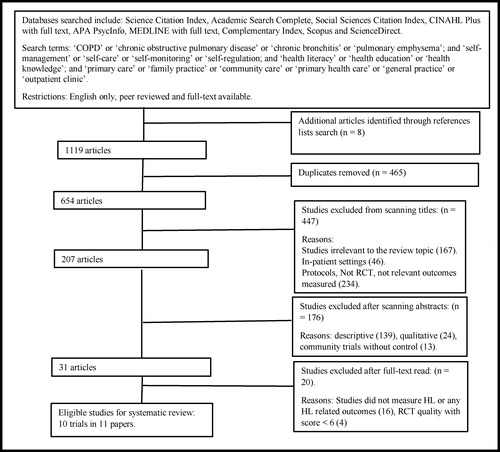

Literature searches were conducted in eight well known data bases including Science Citation Index, Academic Search Complete, Social Sciences Citation Index, CINAHL Plus, APA PsycInfo, MEDLINE, Complementary Index, Scopus and ScienceDirect. The literature was searched to identify trials of COPD self-management interventions that focused on HL in outpatient settings undertaken from 2008 until February 2020 using a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) protocol [Citation33] (see ). Search terms included COPD/Chronic bronchitis/pulmonary emphysema, self-management/self-care/self-monitoring and primary care/general practice/primary health care/family practice/community care/outpatient clinic.

Box 1: Example search strategy for reviewing the effectiveness of health literacy driven COPD self-management interventions in outpatient settings.

(*) means search for the same word with multiple endings such as skill and skills.

Study selection criteria and data extraction

Studies were included if they were RCTs and explicitly described the randomization process and had at least 2 arms (one intervention and one control arm). Inclusion and exclusion criteria are described in .

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Trials were included if they were conducted in outpatient settings including primary care, outpatient clinics or community settings, had at least one measure of HL, had measured COPD self-management outcomes, were peer reviewed and published in English. Trials which were conducted in in-patient settings were excluded. Trials in in-patient settings were excluded because the services and the severity of COPD in these settings are different to those of outpatient settings. The authors independently reviewed the studies against the inclusion and exclusion criteria and made decisions on study selections. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion. Then, data extraction and tabulation was completed by one author and double checked by the coauthors. The quality of the trials were assessed using Cochrane Back Review Group (CBRG) assessment criteria [Citation34].

Intervention classification and outcomes measurements

HL COPD self-management trials in outpatient settings measuring improvement in HL, COPD knowledge, physical activity, self-efficacy, dyspnea, smoking cessation, mental health, medication adherence, hospital admissions and quality of life were reviewed using a PRISMA protocol [Citation33]. The literature was organized using a narrative synthesis due to variability in both the interventions used and the outcomes measured in the studies. Quality of the included studies were assessed using CBRG assessment criteria [Citation34]. Only high quality trials scoring 6 CBRG points or more were included.

Results

Study selection

The literature search identified 1119 potential studies. After removing duplicates (465), 447 studies were also removed as they were not RCT or were conducted in in-patient settings. The remaining 207 studies were assessed for eligibility. Titles and abstracts were reviewed against the inclusion criteria, and only 31 studies met the selection criteria. The full text of the remaining 31 studies were further assessed against the inclusion criteria and 20 studies were excluded as they either did not measure HL or scored low in CBRG RCT quality assessment criteria. Finally, 10 trials were included in the review (see ). However, the findings of one trial reported in two papers. Haesum et al. [Citation35] and Haesum et al. [Citation36] reported the result of one study. The first one provided data for short term HL levels as measured by functional measurements (S-TOFHLA at 3 months) whereas the second one provided data for HL long term (12 months). Demographics and outcomes variable were the same in both studies. That is why we have 10 trials but 11 papers in this review.

Patients’ characteristics

Participants’ demographics in the trials are described in Supplementary Table 1. The proportion of males and females varied between the trials. However, most of the participants were males across the studies ranged between 45.3% and 98.2%. The participants’ age ranged between 60 and 73 years old. The sample size ranged between 52 and 763 patients. In terms of delivery mode, five of the interventions were delivered online, four were delivered face to face and one used both online and face to face methods.

Description of the interventions

Components of the interventions in the reviewed trials are described in Supplementary Table 1. The trials addressed different aspects of HL such as access to health care services, social support, communication with health care providers, self-monitoring and understanding of their disease and its management. The interventions are delivered either face-to-face such as health coaching [Citation37] and tailored education [Citation38–41]; or online or technology based methods such as web based information or telemonitoring devices [Citation35,Citation36,Citation42–45].

The education materials in the trials provided basic information about the disease, the importance of physical activity, breathing skills, smoking cessation, and the correct inhaler techniques [Citation38,Citation42,Citation45]. Some of the trials provided COPD patients with general information [Citation35,Citation36,Citation38,Citation43–45], while others provided information tailored to patients’ needs [Citation37,Citation39–42].

One intervention provided the patients with a pedometer to encourage them to monitor their physical activity levels [Citation45], while another provided an integrated education program for 6 months followed by a tailored education session according to patients’ information needs [Citation40]. The other trials involved engaging with health care providers (either nurses and/or doctors) [Citation35,Citation36,Citation38,Citation41,Citation42,Citation44].

All the included trials had two arms; an intervention group and a usual care group except Nguyen et al. which had three arms; two arms represented the intervention group (one arm received face to face self-management intervention while the second arm received the intervention through using a web site). The duration of the interventions ranged from 3 months [Citation45] to 12 months [Citation36,Citation37,Citation40–42,Citation44].

Trials’ quality

The included trials have a CBRG score of 6 points or more, which indicates moderate or high quality of the study. Double blinding was not feasible in all trials due to the nature of the interventions and inability to blind the patients. However, the majority of studies were single blinded whereby the outcome assessor was blinded to the allocation of the participants. The effectiveness of HL COPD self-management interventions were assessed based on changes in the following outcomes: COPD knowledge, Physical activity, dyspnea, self-efficacy, medication adherence, smoking cessation and changes in endpoint outcomes including hospital admissions and quality of life. Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 summarize the measured variables and outcomes results.

COPD knowledge and HL

Six trials assessed HL in terms of COPD knowledge [Citation37,Citation38,Citation40,Citation43–45] and of these, three studies found significant improvement in patients’ disease understanding [Citation37,Citation44,Citation45]. Three trials assessed HL in terms of functional health literacy using the Short Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (STOFHLA) questionnaire [Citation35,Citation36,Citation39,Citation43] and of those, two trials showed no significant improvement in patients’ functional health literacy between the intervention and control groups [Citation35,Citation36,Citation43]. However, Haesum et al. reported significant improvement in functional HL between the baseline and follow-up periods in both groups [Citation35,Citation36]. Eikelenboom et al. found positive association between HL levels and adopting healthier nutrition and having improved patient activation levels [Citation39].

Physical activity

Seven trials assessed participant physical levels in terms of duration and/or endurance and this improved in four out of seven trials [Citation37–40,Citation42,Citation43,Citation45]. Wan et al. found significant changes in daily step counts without any changes in 6 min walk which was used to assess the endurance of physical activity [Citation45]. Three trials found no changes in patients’ physical activity [Citation37,Citation39,Citation42]. One trial targeted physical activity as the main outcome of the intervention [Citation45].

Self-efficacy

Six trials assessed self-efficacy levels however only one trial significantly improved self-efficacy levels [Citation42]. The other five trials failed to find any improvements in self-efficacy [Citation37,Citation39,Citation42–45]. Eikelenboom et al. targeted self-efficacy as measured by patient activation measure as the primary outcome of the intervention

Dyspnea

Five trials had assessed dyspnea among COPD patients [Citation37,Citation40,Citation42,Citation43,Citation45] and of those only one trial found significant improvement in dyspnea levels [Citation40] and one found mild improvement in dyspnea symptoms in favor of the intervention group [Citation37]. Only Nguyen et al. targeted dyspnea as the primary outcome of the intervention [Citation42].

Smoking cessation

Five trials assessed self-reported smoking cessation rate and of those, only one trial resulted in successful smoking cessation in one third of the patients in the intervention group [Citation38]. The other four trials were not successful in smoking cessation [Citation37,Citation39–41]. Thom et al. reported significant reduction in smoking rates among COPD patients in the intervention group, but this effect was not preserved at 9 months’ follow-up [Citation37].

Mental health

Five trials assessed patients’ mental health using patients’ self-reported questionnaires and this was improved in one trial which included measures of depression and anxiety [Citation38]. Four trials found no positive changes in patients’ mental health [Citation37,Citation41,Citation44,Citation45] and of those, one trial found positive improvement in symptoms of depression but not anxiety at 9 months’ follow-up [Citation37,Citation41]. Another trial showed that patients in the intervention group were less likely to report symptoms of depression at 12 months’ follow-up [Citation41].

Medication adherence and use

Four trials assessed medication adherence using self-reported questionnaires. Only one trial reported increased self-reported use of correct inhaler techniques at both 3 and 12 months [Citation43]. The other two trials found no changes in patients’ self-reported medication adherence and knowledge [Citation40,Citation44]. Likewise, Farmer failed to report positive results regarding patients’ beliefs about their lung medication or adherence [Citation41].

Hospital admissions

Five trials assessed hospital admissions however only one trial significantly decreased hospitalization rates and emergency department visits [Citation40]. The other four trials found no improvements in hospitalization rate between patients in intervention and control groups [Citation37,Citation41,Citation43,Citation44]. Farmer and his colleagues showed reduction in hospitalization rates, but this did not reach significance [Citation41].

Quality of life

Quality of life was assessed using self-reported questionnaires in eight trials but it was improved in one trial only [Citation38]. While the other seven trials failed to report any improvement in measures of quality of life [Citation37,Citation40–45].

Delivery mode: face-to-face methods vs. technology based methods

Interventions delivered technology based methods were more likely to improve physical activities [Citation44,Citation45], COPD knowledge [Citation44], accurate inhaler use [Citation44], and fewer visits to general practice [Citation41]. Whereas, interventions delivered face to face methods were more likely to improve smoking cessation [Citation37,Citation38,Citation40], emotional health [Citation38], quality of life [Citation37,Citation38], self-monitoring [Citation39].

Discussion

This review summarized the most recent RCTs evaluating the effectiveness of health literacy driven interventions on COPD self-management outcomes in outpatient settings.

The interventions of the included trials varied in content, measurement of health literacy, outcome variables, duration, and mode of delivery. Some trials used technology based delivery methods such as website [Citation35,Citation36,Citation41–45], while others used face to face delivery methods like tailored education programs [Citation37–40]. Thus, the findings of our review are interpreted with some caution.

The reviewed trials found moderate improvements in COPD knowledge and physical activity [Citation37–40,Citation42–45]. The interventions had modest effect on dyspnea [Citation40], self-efficacy [Citation42], smoking cessation [Citation38], medication adherence [Citation38,Citation43], quality of life [Citation38] and hospital admissions [Citation40]. In addition, the effect on functional health literacy was not different between patients in intervention and control groups [Citation35,Citation36,Citation43].

Interestingly, some interventions resulted in improving physical activity levels. This is consistent with previous systematic reviews suggesting that HL is a strong predictors of improving physical activity levels [Citation32,Citation46,Citation47].

Medication adherence did not improve in any of the reviewed health literacy interventions, which suggests that providing information through a website is not enough to change patients’ use of medications. In line with a previous systematic review, this finding highlights that combining HL with other strategies such as ‘teach back’ technique may improve patients’ compliance with their medications [Citation48].

Self-efficacy, another important factor in improving health outcomes, did not improve among patients in the reviewed trials except in one trial [Citation42]. This might be explained by the strategies used to address health literacy which mainly focused on improving patients access to health care services through using technology based interventions rather than focusing in building patients’ skills. Thus, there is a strong need to motivate patients and empower them to engage with COPD management activities [Citation16]. Additionally, the emerging evidence suggests that targeting both patient activation and health literacy is more likely to yield positive health outcomes and empower patients to acquire COPD self-management skills [Citation23,Citation49].

Finally, our finding suggests that technology based HL driven COPD self-management interventions are very effective in improving COPD knowledge [Citation44], and fewer visits to general practice [Citation41] compared to those used face to face delivery methods which were more effective in improving smoking cessation [Citation37,Citation38,Citation40], emotional health [Citation38], quality of life [Citation37,Citation38], self-monitoring [Citation39]. These findings suggest online or technology based HL intervention are effective in improving simple behaviors but more complicated behaviors like smoking cessation requires face to face HL interventions. This is not in line with the literature suggesting that using technology mediated intervention is effective in improving quality of life and hospitalization rates [Citation50,Citation51]. Therefore, it warrants further studies.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that health literacy driven COPD self-management interventions carries promising results with respect to improving patients understanding of COPD and physical activity levels. However, further studies are needed to explore how HL can be used to improve most of COPD self-management outcomes including self-efficacy, dyspnea, hospital admissions and health related quality of life.

Limitations

Although this systematic review provides rich information about health literacy interventions among COPD patients in outpatient settings, it has some limitations. The data regarding outcome measurements were not completely reported in all trials. The small sample size in some trials might affect the interpretation of their results. The significant variation in the interventions and measurement tools makes some of the studies difficult to compare for the purposes of this review. In addition, the findings of this review cannot be generalized to in-patient settings and to non-RCT interventions.

Conclusion and future research implications

COPD self-management interventions in outpatient settings improve disease knowledge and physical activity levels, however they are not successful in improving other self-management behaviors and skills such as self-efficacy, dyspnea, hospital admissions and health related quality of life. Using a well-designed trial with larger sample size, robust measurement tools and longer follow-up may improve the effectiveness of HL driven COPD self-management interventions.

Declaration of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (233.6 KB)References

- WHO. Chronic obstructive pulmonar disease (COPD). 2017. [cited 2019 12 June]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-(copd).

- Yadav UN, Lloyd J, Hosseinzadeh H, et al. Self-management practice, associated factors and its relationship with health literacy and patient activation among multi-morbid COPD patients from rural Nepal. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):300. DOI:10.1186/s12889-020-8404-7

- GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1789–1858. DOI:10.1016/s0140-6736(18)32279-7

- WHO. Chronic respiratory diseases: burden of COPD 2019 [cited 2019 23 April]. Available from: https://www.who.int/respiratory/copd/burden/en/.

- Yang IA, Brown JL, George J, et al. COPD-X Australian and New Zealand guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: 2017 update. Med J Aust. 2017;207(10):436–442. DOI:10.5694/mja17.00686

- Jeganathan C, Hosseinzadeh H. The role of health literacy on the self-management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review. COPD. 2020;8:1–8. DOI:10.1080/15412555.2020.1772739

- Ansari S, Hosseinzadeh H, Dennis S, et al. Activating primary care COPD patients with multi-morbidity through tailored self-management support. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2020;30(1):12. DOI:10.1038/s41533-020-0171-5

- Yadav UN, Lloyd J, Hosseinzadeh H, et al. Facilitators and barriers to the self-management of COPD: a qualitative study from rural Nepal. BMJ Open. 2020;10(3):e035700. DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035700

- Zwerink M, Brusse-Keizer M, van der Valk PD, et al. Self management for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(3):CD002990. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD002990.pub3

- Wang T, Tan JY, Xiao LD, et al. Effectiveness of disease-specific self-management education on health outcomes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(8):1432–1446. DOI:10.1016/j.pec.2017.02.026

- Majothi S, Jolly K, Heneghan NR, et al. Supported self-management for patients with COPD who have recently been discharged from hospital: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:853–867. DOI:10.2147/COPD.S74162

- Kruis AL, Boland MR, Assendelft WJ, et al. Effectiveness of integrated disease management for primary care chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: results of cluster randomised trial. BMJ. 2014;349:g5392. DOI:10.1136/bmj.g5392

- Jonkman NH, Westland H, Trappenburg JC, et al. Do self-management interventions in COPD patients work and which patients benefit most? An individual patient data meta-analysis. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:2063–2074. DOI:10.2147/COPD.S107884

- Jolly K, Majothi S, Sitch AJ, et al. Self-management of health care behaviors for COPD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:305–326. DOI:10.2147/COPD.S90812

- Howcroft M, Walters EH, Wood-Baker R, et al. Action plans with brief patient education for exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;12:CD005074. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD005074.pub4

- Hosseinzadeh H, Shnaigat M. Effectiveness of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease self-management interventions in primary care settings: a systematic review. Aust J Prim Health. 2019;25(3):195–204. DOI:10.1071/PY18181

- Mitchell B, Begoray D. Electronic personal health records that promote self-management in chronic illness. Online J Issues Nurs. 2010;15. DOI:10.3912/OJIN.Vol15No03PPT01

- Yadav UN, Hosseinzadeh H, Baral KP. Self-management and patient activation in COPD patients: An evidence summary of randomized controlled trials. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2018;6(3):148–154. DOI:10.1016/j.cegh.2017.10.004

- Yadav UN, Lloyd J, Hosseinzadeh H, et al. Levels and determinants of health literacy and patient activation among multi-morbid COPD people in rural Nepal: findings from a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):e0233488. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0233488

- WHO. Health promotion/health literacy 2019 [20 January 2020]. Available from: https://www.who.int/healthpromotion/health-literacy/en/.

- Nutbeam D. The evolving concept of health literacy. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(12):2072–2078. DOI:10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.050

- Dahal PK, Hosseinzadeh H. Association of health literacy and diabetes self-management: a systematic review. Aust J Prim Health. 2019;25(6):526–533. DOI:10.1071/PY19007

- Yadav UN, Hosseinzadeh H, Lloyd J, et al. How health literacy and patient activation play their own unique role in self-management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)? Chron Respir Dis. 2019;16:1479973118816418. DOI:10.1177/1479973118816418

- Ho T, Hosseinzadeh H, Rahman B, et al. Health literacy and health-promoting behaviours among Australian-Singaporean communities living in Sydney metropolitan area. Proc Singapore Healthc. 2018;27(2):125–131. DOI:10.1177/2010105817741906

- Niknami M, Mirbalouchzehi A, Zareban I, et al. Association of health literacy with type 2 diabetes mellitus self-management and clinical outcomes within the primary care setting of Iran. Aust J Prim Health. 2018;24(2):162–170. DOI:10.1071/PY17064

- Yadav UN, Lloyd J, Hosseinzadeh H, et al. Do chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (COPD) self-management interventions consider health literacy and patient activation? A systematic review. JCM. 2020;9(3):646. DOI:10.3390/jcm9030646

- Omachi TA, Sarkar U, Yelin EH, et al. Lower health literacy is associated with poorer health status and outcomes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(1):74–81. DOI:10.1007/s11606-012-2177-3

- Ross W, Ph M, Culbert A, et al. A theory-based approach to improving health literacy. 2009.

- McCormack L, Thomas V, Lewis MA, et al. Improving low health literacy and patient engagement: a social ecological approach. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(1):8–13. DOI:10.1016/j.pec.2016.07.007

- Walters R, Leslie SJ, Polson R, et al. Establishing the efficacy of interventions to improve health literacy and health behaviours: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1040–1040. DOI:10.1186/s12889-020-08991-0

- Taggart J, Williams A, Dennis S, et al. A systematic review of interventions in primary care to improve health literacy for chronic disease behavioral risk factors. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13(1):49. DOI:10.1186/1471-2296-13-49

- Lundell S, Holmner A, Rehn B, et al. Telehealthcare in COPD: a systematic review and meta-analysis on physical outcomes and dyspnea. Respir Med. 2015;109(1):11–26. DOI:10.1016/j.rmed.2014.10.008

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. DOI:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Furlan AD, Pennick V, Bombardier C, et al. 2009 updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the Cochrane Back Review Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34(18):1929–1941. DOI:10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b1c99f

- Korsbakke Emtekaer Haesum L, Ehlers L, Hejlesen OK. Interaction between functional health literacy and telehomecare: short-term effects from a randomized trial. Nurs Health Sci. 2016;18(3):328–333. DOI:10.1111/nhs.12272

- Haesum L, Ehlers L, Hejlesen OK. The long-term effects of using telehomecare technology on functional health literacy: results from a randomized trial. Public Health. 2017;150:43–50. DOI:10.1016/j.puhe.2017.05.002

- Thom DH, Willard-Grace R, Tsao S, et al. Randomized controlled trial of health coaching for vulnerable patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15(10):1159–1168. DOI:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201806-365OC

- Efraimsson EO, Hillervik C, Ehrenberg A. Effects of COPD self-care management education at a nurse-led primary health care clinic. Scand J Caring Sci. 2008;22(2):178–185. DOI:10.1111/j.1471-6712.2007.00510.x

- Eikelenboom N, van Lieshout J, Jacobs A, et al. Effectiveness of personalised support for self-management in primary care: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66(646):e354–e361. DOI:10.3399/bjgp16X684985

- Wakabayashi R, Motegi T, Yamada K, et al. Efficient integrated education for older patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease using the Lung Information Needs Questionnaire. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2011;11(4):422–430. DOI:10.1111/j.1447-0594.2011.00696.x

- Farmer A, Williams V, Velardo C, et al. Self-management support using a digital health system compared with usual care for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2017;319(5):e144. DOI:10.2196/jmir.7116

- Nguyen HQ, Donesky D, Reinke LF, et al. Internet-based dyspnea self-management support for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;46(1):43–55. DOI:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.06.015

- Nyberg A, Tistad M, Wadell K. Can the COPD web be used to promote self-management in patients with COPD in swedish primary care: a controlled pragmatic pilot trial with 3 month- and 12 month follow-up. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2019;37(1):69–82. DOI:10.1080/02813432.2019.1569415

- Pinnock H, Hanley J, McCloughan L, et al. Effectiveness of telemonitoring integrated into existing clinical services on hospital admission for exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: researcher blind, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2013;347:f6070. DOI:10.1136/bmj.f6070

- Wan ES, Kantorowski A, Homsy D, et al. Promoting physical activity in COPD: insights from a randomized trial of a web-based intervention and pedometer use. Respir Med. 2017;130:102–110. DOI:10.1016/j.rmed.2017.07.057

- Waschki B, Kirsten A, Holz O, et al. Physical activity is the strongest predictor of all-cause mortality in patients with COPD: a prospective cohort study. Chest. 2011;140(2):331–342. DOI:10.1378/chest.10-2521

- Hosseinzadeh H, Verma I, Gopaldasani V. Patient activation and Type 2 diabetes mellitus self-management: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aust J Prim Health. 2020;26(6):431–442. DOI:10.1071/PY19204

- Dantic DE. A critical review of the effectiveness of ‘teach back’ technique in teaching COPD patients self-management using respiratory inhaler. Health Educ J. 2014;73(1):41– 50. DOI:10.1177/0017896912469575

- Smith SG, Curtis LM, Wardle J, et al. Skill set or mind set? Associations between health literacy, patient activation and health. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e74373. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0074373

- Polisena J, Tran K, Cimon K, et al. Home telehealth for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Telemed Telecare. 2010;16(3):120–127. DOI:10.1258/jtt.2009.090812

- McLean S, Nurmatov U, Liu JL, et al. Telehealthcare for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(7):CD007718. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD007718.pub2