Abstract

This study describes the research and healthcare priorities of individuals living with COPD. On an online survey, individuals living with COPD assigned a percentage of funding to 22 research priorities and a percentage of time spent communicating with a healthcare provider to 24 healthcare priorities, indicating which topics were most important. For each research and healthcare priority, we examined the selection frequency of the priority and used chi-square analyses to examine differences in priority selection by quartiles of airflow obstruction (percent predicted forced expiratory volume in 1-sec (FEV1%predicted)) and breathlessness burden and exacerbation risk. Based on participants’ responses (N = 148, 47% women; Mean ± Standard Deviation age = 68 ± 9 yrs) relief of breathlessness was the most often selected research (76% of respondents) and healthcare priority (61% of respondents). It was selected most often, regardless of disease severity or breathlessness burden and exacerbation risk. We found differences for disease severity and breathlessness burden and exacerbation risk in some research priorities (e.g., to improve the maximal amount of exercise of adults living with COPD in and out of the home (χ2(3) = 9.97, Cramer’s V =.28) and healthcare priorities (e.g., increase your ability to exercise (χ2(3) = 9.72, Cramer’s V =.27)). This study provides empirical evidence that relief of breathlessness is a top research and healthcare priority for individuals living with COPD. Future healthcare and research activities should align with the priorities of individuals with COPD to improve their care by minimizing disease/symptom burden and optimizing health-related quality of life.

Introduction

In 2015, the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and European Respiratory Society (ERS) released a joint statement on the current status of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), highlighting the “need for studies that determine which outcomes matter most for [individuals] with COPD” [Citation1]. The authors called for more research exploring the needs of these individuals to ensure that future research aligned with the priorities of people living with COPD. An individual’s priorities regarding their healthcare can be explored through two complimentary avenues: by identifying their priorities for future research and their own healthcare. Research on both avenues is needed to improve COPD care.

Individuals with COPD report having differing healthcare priorities to their healthcare providers [Citation2–4]. Specifically, individuals with COPD prioritize healthcare information, financial support, and the need for palliative care options more than their healthcare providers [Citation2]. Since the ATS/ERS call to action in 2015, there has been some research investigating the healthcare priorities of individuals with COPD using a patient-oriented approach. Poureslami and colleagues [Citation5] engaged individuals with COPD and asthma as partners to identify recommendations for patient participation in health research. They identified three broad healthcare priorities: origin of disease; development of new therapies; and patient education. Although these priorities can provide an initial direction for healthcare providers and researchers to optimize COPD care and prioritize clinical research, they fail to capture the direct needs of individuals with COPD. To better equip the healthcare system with the tools needed to address the needs of people with COPD, clinical research must also align with the healthcare priorities of these individuals.

To understand the priorities of individuals living with COPD and to better align future research with their needs, a comprehensive examination of patient research priorities is necessary. Identifying the research priorities of this population can help clinical researchers conduct meaningful research that has a higher chance of patient engagement [Citation6] and work to ensure that their research activities are meeting the needs of the patient population, first and foremost [Citation7]. An exploration of both the research and healthcare priorities can help guide future research programs and give healthcare providers a better understanding of the needs of their patients with the end goal of optimizing the management and health outcomes of individuals living with COPD.

The primary aim of this exploratory study was to identify the healthcare and research priorities of individuals with COPD. The secondary aim was to explore the differences in the healthcare and research priorities of individuals with COPD by (i) disease severity and (ii) breathlessness burden and exacerbation risk.

Methods

Patient-engagement

The Activities, Healthcare, and Research Priorities Survey (AHRPS) was created to identify the needs of individuals living with COPD. Individuals’ priorities were divided into three categories: participation in daily and social activities, healthcare, and research. Our earlier study addressed individuals’ activity and participation priorities [Citation8], while this study addressed individuals’ healthcare and research priorities.

Patient engagement is “the meaningful and active collaboration in governance, priority setting, conducting research, and knowledge translation between researchers and patients.” [Citation7] It allows the patients’ priorities to be integrated into research projects to target or identify relevant outcomes. In this study, individuals with COPD were engaged throughout the research process, which included development of the AHRPS and interpretation of results. Individuals with COPD were engaged in the development through five focus groups (N = 25; 27% female) and two working group meetings that involved researchers, clinicians, and industry partner representatives. See our previous paper [Citation8] as well as the supplemental document for details on AHRPS development (Appendix A).

Participants and recruitment

A minimum sample size of 200 participants was selected for this exploratory study. Participants were recruited from five tertiary care respiratory outpatient clinics in the Greater Montreal Area between December 2016 and October 2017. To be eligible to participate, individuals had to be a) diagnosed with COPD by a respirologist; b) above the age of 35 years; and c) able to read and write in English or French. Eligible participants were either sent a link to the survey via email or completed the survey by telephone with a research assistant. Prior to starting the survey, all participants provided informed consent. Approval for the study was obtained from the corresponding hospital research ethics board (ethical approval #: 15-203-MUHC) and the study was registered (clinicaltrials.gov protocol ID#: NCT02970422).

Measures

Priorities. A modified willingness-to-pay method [Citation9] was used to capture our participant’s research and healthcare priorities. This method allows individuals to assign preference to various priorities by assigning a percentage value to a priority. In our survey, participants identified priorities by assigning a percentage of either time or funding to a maximum of 10 priorities (giving between 10% and 100% to one priority).

Research and healthcare priorities. Participants were presented, in random order, with a list of 22 possible COPD-related research priorities and 24 possible COPD-related healthcare priorities. In increments of 10%, participants assigned a percentage of funds to any of the 22 research priorities or a percentage of time to any of the 24 healthcare priorities they would like to discuss with their healthcare provider.

Demographics. Individuals reported their ethnicity, marital status, employment status, total household income, and highest level of education achieved. Participants were also asked: to identify the year they were diagnosed with COPD by a healthcare provider; if they had ever completed pulmonary rehabilitation (PR); and about their tobacco smoking habits. Additionally, participants completed the Charlson co-morbidity index [Citation10], modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnea questionnaire [Citation11], and COPD assessment test (CAT) [Citation12].

Medical charts. Data retrieved from participants’ medical charts included: sex; age; height; body mass; forced expiratory volume in 1-sec (FEV1); FEV1-to-forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio; and exacerbation history from the past 12 months. FEV1 was expressed as a percentage of the age, sex, and height predicted normal values of the Canadian population (FEV1% predicted) [Citation13]. The FEV1/FVC lower limit of normal (LLN) ratio was also calculated for each participant, using the equation in Tan et al. [Citation13] Both the LLN and the fixed FEV1/FVC ratio of <0.70 were used to determine if participants spirometric values were indicative of COPD. For this study, an exacerbation was defined as a change in medication due to an exacerbation (i.e., the prescription of prednisone or a medical action plan), as indicated in the medical chart, and/or hospital admission due to an exacerbation.

Data analysis

Individuals with a measured FEV1/FVC < LLN and/or a FEV1/FVC <0.70 were divided into quartiles of disease severity based on their FEV1% predicted. Quartiles 1, 2, 3 and 4 represented mild (Q1), moderate (Q2), severe (Q3) and very severe (Q4) airflow obstruction, respectively. Quartiles of FEV1% predicted were used instead of the Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) COPD staging system [Citation14] because we were not able to confirm that spirometry was done post-bronchodilator for all individuals.

Breathlessness burden and exacerbation risk group classifications were based on mMRC scores and 12 month exacerbation history [Citation14]: group A, mMRC ≤1 with ≤1 exacerbation that did not lead to hospital admission (low breathlessness + low exacerbation risk); group B, mMRC ≥2 with ≤1 exacerbation not leading to hospital admission (high breathlessness + low exacerbation risk); group C, mMRC ≤1 with ≥2 exacerbations or ≥1 exacerbation that led to hospital admission (low breathlessness + high exacerbation risk); and group D, mMRC ≥2 and ≥2 exacerbations or >1 exacerbation that led to hospital admission (high breathlessness + high exacerbation risk).

Descriptive statistics were used to report individuals’ research and healthcare priorities. The overall selection frequency was assessed to identify the most commonly selected healthcare and research priorities. As well, for each priority we assessed the number of respondents for the (i) quartiles of airflow obstruction and (ii) breathlessness burden and exacerbation risk groups. Using IBM SPSS Statistical software (v.23), chi-square analyses, with standardized residuals post-hoc analyses, were performed to determine if the observed number of participants who selected each research or healthcare priority (i.e., responders) differed from the statistically expected value for (i) the quartiles of airflow obstruction and (ii) the breathlessness burden and exacerbation risk groups. Additionally, non-parametric tests were conducted separately for the breathlessness burden and exacerbation risk groups to examine if there were significant interactions between groups for both the healthcare and research priorities. A Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test was conducted due to the non-normality of the data, as the mean for both research and healthcare priorities was skewed. Post-hoc analyses with Bonferroni corrections were also conducted. Statistical significance was accepted at alpha <0.05.

Results

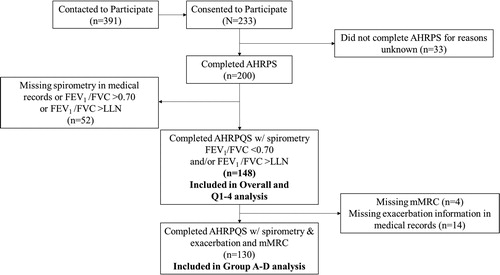

Two hundred thirty-three individuals consented to participate in this study and 200 completed the AHRPS. One-hundred forty-eight individuals had a FEV1/FVC < LLN or a FEV1/FVC <0.70 and were included in the analyses (64% complete rate; 47% women; Mage = 68, SD = 9; ; ). Of these 148 participants, 45% had previously completed PR, 38% had an exacerbation in the past 12 months, and 67% had a mMRC score ≥2 ().

Figure 1. Participant flow chart.

Abbreviations: Activities, Healthcare and Research Priorities Survey (AHRPS); Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD); forced expiratory volume in 1-sec (FEV1); Forced vital capacity (FVC); Lower Limit of Normal (LLN); Quartiles 1-4 of airflow obstruction (Q1-4); modified Medical Research Council breathlessness questionnaire (mMRC); breathlessness burden and exacerbation risk groups A-D (Group A-D).

Table 1. Participants demographic information by quartiles of disease severity.

The 148 participants were divided into four quartiles of disease severity: Q1 (mild): n = 37; FEV1%predicted = 79.0 ± 21.5 (mean ± SD); Q2 (moderate): n = 3; FEV1%predicted = 55.6 ± 5.5; Q3 (severe): n = 37; FEV1%predicted = 38.5 ± 4.8; and Q4 (very severe): n = 37; FEV1%predicted = 25.2 ± 4.5. Of the 148 individuals included in this analysis, 41 indicated they also had a co-diagnosis of asthma. However, there were no differences in the research or healthcare priorities of individuals with or without co-existent asthma ().

For breathlessness burden and exacerbation risk groups, 130 participants had both exacerbation history and mMRC data, which were used to divide individuals in the groups (). The four groups were: Group A, low breathlessness + low exacerbation risk (n = 27; FEV1%predicted = 58.1 ± 7.3; FEV1/FVC = 58.1 ± 7.3%); Group B, high breathlessness + low exacerbation risk (n = 50; FEV1%predicted = 47.9 ± 11.2; FEV1/FVC = 47.9 ± 11.2%); Group C, low breathlessness + high exacerbation risk (n = 14; FEV1%predicted = 49.1 ± 12.8; FEV1/FVC = 49.1 ± 12.8%); and Group D, high breathlessness + high exacerbation risk (n = 40; FEV1%predicted = 44.5 ± 12.0; FEV1/FVC = 44.5 ± 12.0%).

Research priorities

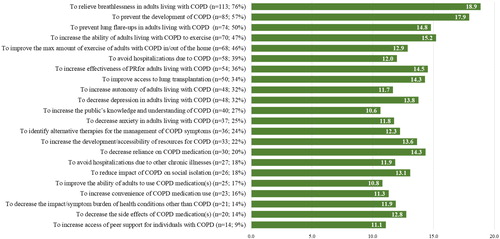

Across the 148 participants, to relieve breathlessness in adults living with COPD was the research priority selected most often (76%), followed by to prevent the development of COPD (57%), to prevent lung flare-ups in adults living with COPD (50%), to increase the ability of adults living with COPD to exercise (47%), and to improve the maximal amount of exercise in and out of the home (46%; ; ). On average, participants assigned 18.9% of research funds to relieve breathlessness in adults living with COPD and 17.9% of funding for research to prevent the development of COPD, making these the top two research priorities by percent funding allocation.

Figure 2. Overall research priorities (n = 148).

Note: Research priorities presented in descending order from the priority selected by the most participants to the priority selected by the least participants.

Table 2. Top five research priorities by frequency of selection.

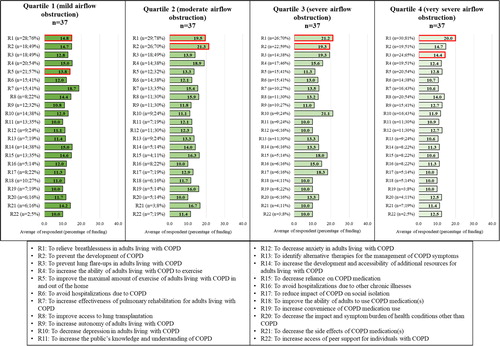

The research priority selected most often, across disease severity quartiles, was to relieve breathlessness in adults living with COPD (76%, 78%, 70%, and 81% in Q1 to 4, respectively; ; ). The second most commonly selected research priority among participants in Q1 (57%) was to improve the maximal amount of exercise of adults living with COPD in and out of the home, in Q2 and Q3 was to prevent the development of COPD (70% and 59%, respectively), and in Q4 (65%) was to prevent lung flare-ups in adults living with COPD (). To relieve breathlessness in adults living with COPD was also selected most often by individuals in breathlessness burden and exacerbations groups A (74%), B (80%) and D (78%). Individuals in group C selected to prevent the development of COPD most often (64%; ; ). These priorities were followed by to prevent the development of COPD for groups A (56%) and B (60%), to improve access to lung transplantations in group C (57%), and to prevent lung flare-ups in adults with COPD in group D (53%).

Figure 3. Research priorities by quartiles of airflow obstruction (n = 148).

Note: Research priorities are presented in the same order as the overall priorities in , and not by frequency of selection. The percentage value beside each priority represents the percentage of individuals in the quartile who selected the priority. The first and second most commonly selected research priorities in each quartile are outlined in red.

Figure 4. Research priorities by breathlessness burden and exacerbation risk group classification (n = 130).

Note: Research priorities are presented in the same order as the overall priorities in , and not by the frequency of selection. The percentage value beside each priority represents the percentage of individuals in the group who selected the priority. The first and second most commonly selected research priorities in each group are outlined in red.

The number of participants who selected research priorities differed by the quartiles of disease severity and the breathlessness burden and exacerbation risk groups. To relieve breathlessness in COPD () was selected by fewer responders in Q1 than expected (O = 26, E = 33; AR = −2.7). To improve access to lung transplantations () was selected by fewer responders in Q2 than expected (O = 10, E = 15.8; AR = −2.1) and more responders in Q4 than expected (O = 26, E = 15.8; AR = 3.7). Lastly, to increase the effectiveness of pulmonary rehabilitation for adults living with COPD was selected by fewer responders in Q4 than expected (O = 9, E = 17.9; AR = −3.1; ). No significant interactions were observed between the quartiles of airflow obstruction and the research priorities.

Table 3. Chi-squared (χ2) for research priorities of each comparison group.

For breathlessness burden and exacerbation history, we found that to improve the maximal amount of exercise of adults living with COPD in and out of the home () was selected by fewer responders in group A (O = 11, E = 18.7; AR = −2.8) and more responders in group B than expected (O = 37, E = 28.5; AR = 2.8). To avoid hospitalizations due to COPD was selected by fewer responders in group B than expected (O = 14, E = 23.3; AR = −3.1; ). To increase the development and accessibility of additional resources for adults living with COPD had more responders in group B (O = 20, E = 12.6; AR = 3.0) and fewer in group D than expected (O = 4, E = 10.1; AR = −2.6; ). Lastly, more responders in group C selected to increase the public’s knowledge and understanding of COPD than expected (O = 9, E = 4.3; AR = 2.8; ). No significant interactions were observed between breathlessness burden and exacerbation risk groups and research priorities.

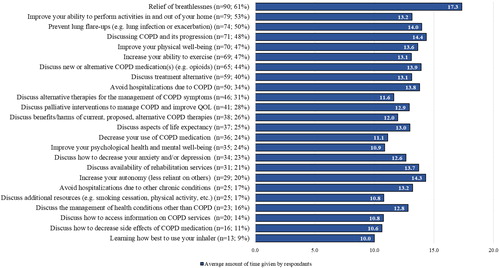

Healthcare priorities

Relief of breathlessness was identified most often as a healthcare priority (61%) across all 148 participants, followed by improve your ability to perform activities in and out of your home (53%), prevent lung flare-ups (50%), discussing COPD and its progression (48%), and improve your physical well-being (47%; ). On average, participants assigned 17.3% and 13.2% of their time speaking with a healthcare provider to relief of breathlessness and discussing COPD and its progression, respectively ().

Figure 5. Overall healthcare priorities (n = 148).

Note: Healthcare priorities presented in descending order from the priority selected by the most participants to the topic selected by the least participants. Abbreviations: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD); Quality of life (QOL).

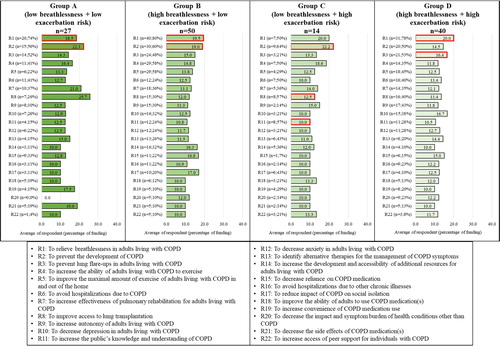

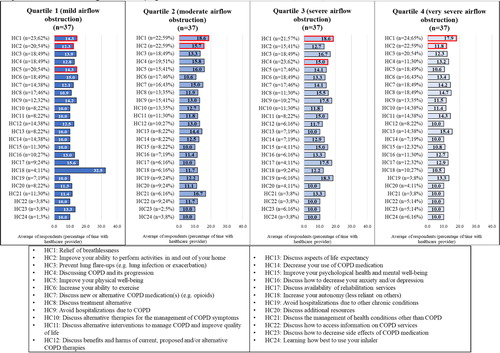

Relief of breathlessness was most often selected as a healthcare priority by individuals with mild (Q1, 62%), moderate (Q2, 59%), and very severe (Q4, 65%) airflow obstruction (; ), while discussing COPD and its progression was most often selected by individuals with severe airflow obstruction (Q3, 62%; ). Improve your ability to perform activities in and out of your home was the second most commonly selected healthcare priority by individuals in Q1 (54%), Q2 (59%) and Q4 (59%), whereas those in Q3 selected relief of breathlessness (57%; ).

Figure 6. Healthcare priorities by quartiles of airflow obstruction (n = 148).

Note: Healthcare priorities are presented in the same order as the overall priorities in , and not the frequency of selection. The percentage value beside each priority represents the percentage of individuals in the quartile who selected the priority. The first and second most commonly selected healthcare priorities in each quartile are outlined in red.

Table 4. Top five healthcare priorities by frequency of selection.

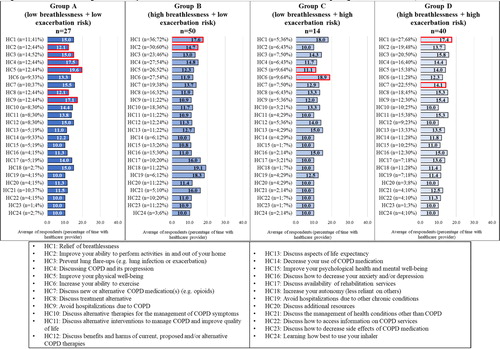

Prevent lung flare-ups was selected most often by people in group A with low breathlessness burden + low exacerbation risk (52%), while both improve your physical well-being and increase your ability to exercise were selected most often by people in group C with low breathlessness burden + high exacerbation risk (64% for both; ; ). People in groups B and D with high breathlessness burden most often selected relief of breathlessness as a healthcare priority (72% and 68%, respectively; ). Improve your ability to perform activities in and out of your home was the second most commonly selected healthcare priority among people in groups A (44%) and B (60%) with low exacerbation risk ().

Figure 7. Healthcare priorities by breathlessness burden and exacerbation risk group classification (n = 130).

Note: Research priorities are presented in the same order as the overall priorities in , and not by the frequency of selection. The percentage value beside each priority represents the percentage of individuals in the group who selected the priority. The first and second most commonly selected research priorities in each group are outlined in red.

Between the quartiles of airflow obstruction, we found differences in the observed and expected values for only two healthcare priorities (). Discussing COPD and its progression was selected by more responders in Q3 (O = 23, E = 17.8; AR = 2.0) and fewer responders in Q4 than expected (O = 11, E = 17.8; AR = −2.6) (). Discuss the management of health conditions other than COPD was selected by more responders in Q1 than expected (O = 11, E = 5.8; SR= 2.8). Similarly, discuss the management of health conditions other than COPD was also selected by more responders in group A than expected (O = 10, E = 4.2; AR = 3.5). No significant interactions were observed between the healthcare priorities and quartiles of airflow obstruction.

Table 5. Chi-squared (χ2) for healthcare priorities of each comparison group.

Other healthcare priorities that differed from the expected value were relief of breathlessness, increase your ability to exercise, and discuss how to decrease side effects of COPD medication (). There were more respondents in group B (O = 36, E = 30.4; AR = −2.1) and less in groups A (O = 11, E = 15.8; AR = −2.2) and C (O = 5, E = 8.5; AR = −2.0) who selected relief of breathlessness as a healthcare priority than expected. For increase your ability to exercise, there were more responders in group B (O = 27, E = 21.5; AR = 2.0) and less in group D than expected (O = 27, E = 21.5; AR = 2.0). More individuals in group B than expected selected discuss how to decrease side effects of COPD medication (O = 11, E = 5.4; AR = 3.3). No significant interactions were observed between the healthcare priorities and the breathlessness burden and exacerbation history groups.

Discussion

This study found that individuals with COPD, regardless of their degree of airflow obstruction or breathlessness burden and exacerbation risk, identified most often relief of breathlessness as an important research and healthcare priority. Other commonly identified research and healthcare priorities included: increasing the ability of individuals living with COPD to exercise/participate in activities in their homes, prevent lung flare-ups (exacerbations), and prevent the development of COPD.

Breathlessness is the primary symptomatic manifestation of COPD [Citation15] and associated with adverse health outcomes, including premature death [Citation16]. Relief of breathlessness is currently a top priority of Canadian and international clinical practice recommendations [Citation17, 18] and a focus of the ATS/ERS call-to-action in 2015 [Citation1]. This study supports these recommendations and calls-to-action as breathlessness was identified as a top research and healthcare priority for individuals with COPD. However, effective management of breathlessness in people with COPD is a major challenge for many healthcare providers. More than 50% of adults with COPD reportedly suffer from severe and disabling breathlessness, despite optimal treatment of their underlying pulmonary pathophysiology with inhaled medications [Citation19, Citation20]. Furthermore, we recently identified breathlessness as the top barrier to people with COPD participating in daily and social activities [Citation8]. These findings, therefore, align with previous research on the burden of breathlessness [Citation21].

Relief of breathlessness was also assigned the largest percentage of research funding and time spent discussing with a healthcare provider compared to all other possible healthcare and research priorities. The collective results of our past [Citation8] and current study highlight a seemingly urgent need for future research to identify more effective symptom (breathlessness)-specific strategies to alleviate breathlessness and improve health status and quality of life in people with COPD. These strategies may include, but are not limited to, systemic opioids [Citation22, Citation23], inhalation of L-menthol [Citation24], cognitive behavioral therapy [Citation25], fan-to-face therapy [Citation26–28], or acupuncture [Citation29]. The results of our research highlight the need for healthcare providers to prioritize discussions with their COPD patients around breathlessness and its management. Williams and colleagues [Citation30] recently provided a framework for healthcare providers to help better explain chronic breathlessness to their patients.

Our participants also commonly selected prevent lung flare-ups (exacerbations) as an important research and healthcare priority, regardless of their degree of airflow obstruction or breathlessness burden and exacerbation risk. Similar to relief of breathlessness, the prevention of pulmonary exacerbations aligns with priorities of COPD management according to Canadian practice recommendations [Citation18] and the global strategy for prevention, diagnosis and management of COPD created by GOLD [Citation14]. Identifying more effective ways to not only prevent but also detect and treat (as early as possible) exacerbations of COPD should be a priority focus of researchers, healthcare providers, biopharmaceutical companies, and research funding agencies.

Our participants also commonly selected improve your ability to perform activities in and out of your home as a healthcare priority and to increase the ability of adults living with COPD to exercise and improve the maximal amount of exercise adults living with COPD in and out of the home as research priorities. Identifying ways to facilitate and increase physical activity participation is of importance given the low rate of participation in people with COPD [Citation31] and its potential to reduce breathlessness [Citation32]. These findings also align with those of our earlier study wherein we found that people with COPD wanted to increase their participation in physical activity and movement-related activities (e.g., climbing up two or more flights of stairs) more than several other types of activities, including social engagement and self-care activities [Citation8]. Practically, healthcare providers are encouraged to inform their patients of physical activity resources and programs (e.g., pulmonary rehabilitation, community groups, online interventions) while researchers are encouraged to identify new ways to promote sustained physical activity and movement-related activities for people with COPD.

Across both the quartiles of disease severity and breathlessness burden and exacerbation risk groups, prevent the development of COPD was one of the most commonly selected research priorities. By selecting this priority, participants expressed a need for disease prevention initiatives, in addition to disease management research. Public health initiatives and policy changes are needed to increase individuals’ education on COPD risk factors and minimize their exposure to established risk factors, such as, cigarette smoke and pollution [Citation14]. Additionally, research on genetic susceptibility to COPD and its developmental origins can help further our understanding of prevention targets for individuals living with COPD [Citation33]. Primary prevention initiatives should be undertaken to find ways to reduce individuals’ overall risk of developing COPD and reducing the overall burden of COPD on the healthcare system. Various foci are needed to cover the breadth of research priorities expressed by participants in this study.

Each research and healthcare topic was selected by at least 9% of responders, and most responders allocated time/funding to 10 research and 10 healthcare priorities. This diversity of priorities was exemplified by the differences between the quartiles of disease severity and breathlessness burden and exacerbation risk groups. For instance, Q4 was the only quartile that included to improve access to lung transplantation as a top research priority. With a mean FEV1%predicted of 25.2 (range: 14.7–31.5; ), Q4 was the only group that was potentially eligible for lung transplantation according to established guidelines [Citation34, Citation35]. Further, individuals in Group B also had selected certain research priorities more than expected (e.g., to increase the development and accessibility of additional resources (e.g., smoking cessation, physical activity, nutrition) for adults living with COPD). As a result, the range of selected priorities demonstrates a continued need for a breadth of COPD research for this population. As well, healthcare providers should aim to understand their patients’ individual priorities and needs, as they may vary based on disease severity and/or breathlessness burden and exacerbation risk groups.

Methodological considerations

Participants were included in the study if they had a FEV1/FVC <0.70 and/or a FEV1/FVC < LLN. The LLN was used to confirm COPD and is considered a more stringent criterion for identifying individuals with definite airflow obstruction and minimizing over-diagnosis of COPD [Citation36]. However, the fixed ratio was also used as the criterion is seen as a valid and accurate way of identifying airflow obstruction, with only a small chance of over-diagnosis [Citation36].

As in our previous publication [Citation8], disease severity was not calculated based on the GOLD I-IV classification system [Citation14]. We used quartiles of airflow obstruction because we could not ensure that all spirometric pulmonary function tests were done post-bronchodilator. Any comparisons with other COPD populations using GOLD I-IV are limited, although mean values of FEV1%predicted in Q1-4 were consistent with those used in the GOLD I-IV staging criteria, respectively. As per GOLD ABCD criteria [Citation14], breathlessness burden and exacerbation risk groups were created using mMRC scores and exacerbation history from the preceding 12 months. Participants responded to the mMRC at the same time as they completed the AHRPS, whereas 12 month exacerbation history was pulled from each of our participants’ electronic medical charts after all AHRPS responses had been obtained. Exacerbations were indicated if there was proof of a hospital admission and/or change in medication (i.e., use of medical action plan). We cannot rule out the possibility that exacerbations were missed or mislabeled when data were being collected via review of electronic medical charts.

Conclusion

In response to the 2015 ATS/ERS call for research to identify the outcomes that matter most to individuals living with COPD, we have provided empirical evidence that relief of breathlessness is a top research and healthcare priority for individuals living with COPD, regardless of their degree of airflow obstruction or breathlessness burden and exacerbation risk. Our previous research further supports this notion by demonstrating that an individual’s participation in daily and social activities is primarily limited by breathlessness [Citation8]. Taken together, we hope that the results of our past [Citation8] and current research will help healthcare providers, researchers, biopharmaceutical companies, and granting agencies better align their respective clinical, scientific, research and development, and strategic funding priorities with outcomes that matter most to adults living with COPD. Aligning future healthcare and research activities with COPD patient priorities has the greatest potential to improve COPD care by minimizing disease/symptom burden and optimizing health-related quality of life.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Jean Bourbeau, Dr. Nathalie Saad, Dr. Gregory Moullec, Dr. Benjamin M. Smith, Dr. Nicole Ezer, and Dr. Ronald Dandurand for their contribution to this project. The authors would also like to thank the two individuals living with COPD who actively participated in the working group and shared their experiences to ensure the AHRPS represented the needs of individuals living with COPD. Lastly, the authors would like to thank Alexandra Schram, Frank Niro and Evan Bishop for their help throughout this project, particularly as it related to recruiting participants.

Declaration of interest

In accordance with Taylor & Francis policy and our ethical obligation as researchers, we are reporting that Dr. Jensen received Investigator Initiated Funding from AstraZeneca Canada, which may have affected the research reported in the enclosed paper. We have disclosed those interests fully to Taylor & Francis, and we have in place an approved plan for managing any potential conflicts arising from the funding and research salary support. No potential conflict of interest was reported by the other authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Celli BR, Decramer M, Wedzicha JA, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: research questions in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2015;45(4):879–905. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00009015

- Cooke M, Campbell M. Comparing patient and professional views of expected treatment outcomes for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a Delphi study identifies possibilities for change in service delivery in England, UK. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(13-14):1990–2002. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12459

- Disler RT, Green A, Luckett T, et al. Experience of advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: metasynthesis of qualitative research. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;48(6):1182–1199. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.03.009

- Elkington H, White P, Addington-Hall J, et al. The healthcare needs of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients in the last year of life. Palliat Med. 2005;19(6):485–491. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1191/0269216305pm1056oa

- Poureslami I, Pakhale S, Lavoie KL, et al. Patients as research partners in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma research: priorities, challenges and recommendations from asthma and COPD patients. Can J Respir Crit Care Sleep Med. 2018;2(3):138–146. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/24745332.2018.1443294

- Bell T, Vat LE, McGavin C, et al. Co-building a patient-oriented curriculum in Canada. Resarch Involv Engagem. 2019;5(7):1–13. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-019-0141-7

- Canadian Institute of Health Research. Strategy for patient-oriented research: patient engagement framework. Published 2014. p. 1–11 [accessed 2015 Apr 26]. Available from: http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/48413.html

- Michalovic E, Jensen D, Dandurand RJ, et al. Description of participation in daily and social activities for individuals with COPD. COPD J Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2020;17(5):543–556. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/15412555.2020.1798373

- Kawata AK, Kleinman L, Harding G, et al. Evaluation of patient preference and willingness to pay for attributes of maintenance medication for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Patient. 2014;7(4):413–426. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-014-0064-1

- Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, et al. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47(11):1245–1251. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/0895-4356(94)90129-5

- Fletcher CM. Standardised questionnaire on respiratory symptoms: a statement prepared and approved by the MRC Committee on the Aetiology of Chronic Bronchitis (MRC breathlessness score). Br Med J. 1960;2:1665.

- Jones PW. St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire Original English Version St. George’S Respiratory Questionnaire (Sgrq). Published 2014.

- Tan WC, Bourbeau J, Hernandez P, et al. Canadian prediction equations of spirometric lung function for Caucasian adults 20 to 90 years of age: results from the Canadian Obstructive Lung Disease (COLD) study and the Lung Health Canadian Environment (LHCE) study. Can Respir J. 2011;18(6):321–326. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/540396

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Global strategy for prevention, diagnosis and management of COPD. Gold Rep. 2019.

- Müllerová H, Lu C, Li H, et al. Prevalence and burden of breathlessness in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease managed in primary care. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e85540; 1–12. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0085540

- Nishimura K, Izumi T, Tsukino M, et al. Dyspnea is a better predictor of 5-year survival than airway obstruction in patients with COPD. Chest. 2002;121(5):1434–1440. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.121.5.1434

- Vogelmeier C, Criner G, Martinez F, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease 2017 report: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;53(3):128–149. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arbr.2017.02.001

- Bourbeau J, Bhutani M, Hernandez P, et al. CTS position statement: pharmacotherapy in patients with COPD—an update. Can J Respir Crit Care Sleep Med. 2017;1(4):222–241. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/24745332.2017.1395588

- Sundh J, Ekström M. Persistent disabling breathlessness in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. COPD. 2016;11(1):2805–2812. DOI:https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S119992

- Carette H, Zysman M, Morelot-Panzini C, et al. Prevalence and management of chronic breathlessness in COPD in a tertiary care center. BMC Pulm Med. 2019;19(1):1–7. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-019-0851-5

- Annegarn J, Meijer K, Passos VL, et al. Problematic activities of daily life are weakly associated with clinical characteristics in COPD. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(3):284–290. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2011.01.002

- Abdallah SJ, Wilkinson-Maitland C, Saad N, et al. Effect of morphine on breathlessness and exercise endurance in advanced COPD: a randomised crossover trial. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(4):1701235. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01235-2017

- Verberkt CA, Van Den Beuken-Van Everdingen MHJ, Schols JMGA, et al. Effect of sustained-release morphine for refractory breathlessness in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on health status: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(10):1306–1314. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3134

- Kanezaki M, Terada K, Ebihara S. Effect of olfactory stimulation by L-menthol on laboratory-induced dyspnea in COPD. Chest. 2020;157(6):1455–1465. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2019.12.028

- Williams MT, Johnston KN, Paquet C. Cognitive behavioral therapy for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: rapid review. COPD. 2020;15:903–919. DOI:https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S178049

- Marchetti N, Lammi MR, Travaline JM, et al. Air current applied to the face improves exercise performance in patients with COPD. Lung. 2015;193(5):725–731. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00408-015-9780-0

- Luckett T, Phillips J, Johnson MJ, et al. Contributions of a hand-held fan to self-management of chronic breathlessness. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(2):1700262. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00262-2017

- Swan F, Booth S. The role of airflow for the relief of chronic refractory breathlessness. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2015;9(3):206–211. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1097/SPC.0000000000000160

- von Trott P, Oei SL, Ramsenthaler C. Acupuncture for breathlessness in advanced diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;59(2):327–338.e3. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.09.007

- Williams MT, Lewthwaite H, Brooks D, et al. Chronic breathlessness explanations and research priorities: findings from an international Delphi survey. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;59(2):310–319.e12. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.10.012

- Watz H, Pitta F, Rochester CL, et al. An official European respiratory society statement on physical activity in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(6):1521–1537. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00046814

- McCarthy B, Casey D, Devane D, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2015;2(2):003793. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003793.pub3

- Wan ES. Examining genetic susceptibility in acute exacerbations of COPD. Thorax. 2018;73(6):507–509. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-211106

- O’Donnell DE, Aaron S, Bourbeau J, et al. Canadian Thoracic Society recommendations for management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease – 2007 update. Can Respir J. 2007;14(suppl b):5B–32B. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1155/2007/830570

- Verleden GM, Dupont L, Yserbyt J, et al. Recipient selection process and listing for lung transplantation. J Thorac Dis. 2017;9(9):3372–3384. DOI:https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2017.08.90

- Dijk WV, Tan W, Li P, et al. Clinical relevance of fixed ratio vs lower limit of normal of FEV 1/FVC in COPD: patient-reported outcomes from the CanCOLD cohort. Ann Family Med. 2015;13(1):41–48. DOI:https://doi.org/1070/afm.1714.

Appendix A

Activities, Healthcare and Research Priorities Survey (AHRPS): Patient engagement and survey development

In the survey development phase of our research, individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or COPD (N = 25, 27% women) participated in one of five focus groups to gather their thoughts and opinions on the healthcare and research priorities, as well as the format of the survey. During the focus groups, individuals were presented with a list of 21 possible healthcare priorities and 20 possible research priorities derived from a literature search and review by an expert panel of COPD clinicians and researchers (n = 8). Individuals with COPD were asked to comment, edit, or remove any listed topics or add missing topics. Two research priorities were removed from the list of topics (to develop strategies and intervention to improve psychological health [e.g. anxiety, depression] and to increase the quality of patient care) as the individuals with COPD indicated they were not specific/clear enough. Three research priorities were added, either to better clarify a removed priority (e.g., to decrease depression in adults living with COPD) or as a new priority of interest (to increase access of peer support for individuals with COPD (i.e., speak with others about living with COPD)). Two healthcare priorities were also added during the focus groups: avoid hospitalizations due to other chronic conditions and discuss how to access/obtain information on COPD services available in the community and online.

Individuals also tested the usability of the survey platform and the willingness-to-pay method (see measures section of manuscript for details on this method to capture individuals’ priorities)9. The willingness-to-pay method was used to capture the amount of research funding or the percentage of time individuals wanted to dedicate towards specific research and healthcare priorities, respectively. Participants agreed on the ease to navigate through the survey. Individuals understood the willingness-to-pay method but found it difficult to remember remaining percentages of time/funding once they begun assigning them. For this reason, a survey function to limit the percentage to 100% of time/funding was added. Also, we further clarified and expanded on the description of each question based on the comments of focus group participants.

After the focus groups were conducted, we had a working group meeting with the clinicians and researchers involved in the project, two individuals with COPD (one female, one male), and industry partner representatives. The purpose of this working group meeting was to finalize the survey and make sure it aligned with the possible healthcare and research priorities of individuals living with COPD. During this meeting, we further clarified wording of the survey (e.g., added the word “exacerbations” to the lung flare-up description) and added a research and healthcare priority. To identify alternative therapies for the management of COPD symptoms (e.g., opioids) was added as a possible research priority, while discuss alternative therapies for the management of COPD symptoms was added to the list of possible healthcare priorities. Lastly, the survey was pilot tested by ten individuals with COPD who provided feedback on the usability of the survey, the wording of the questions, and the time to completion.

Once data collection and preliminary analyses were completed, a second working group meeting was held to help with the interpretation of the results. The second working group consisted of the two individuals with COPD and the clinicians and researchers who took part in the initial working group. During this meeting, individuals with COPD indicated that they would use the list of research and healthcare priorities to direct their conversations with their healthcare providers. Clinicians wanted the five most frequently selected healthcare and research priorities presented clearly to enable them to easily gather and use this information. Additionally, the working group suggested that the findings be looked at both through individual’s degree of airflow obstruction or disease severity (specifically forced expiratory volume in 1-sec [FEV1] expressed as a percent of predicted normal FEV1) and the extent of their breathlessness burden and exacerbation risk as per the Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease ABCD criteria14.