Abstract

The “contingent valuation” method is used to quantify the value of services not available in traditional markets, by assessing the monetary value an individual ascribes to the benefit provided by an intervention. The aim of this study was to determine preferences for home or center-based pulmonary rehabilitation for participants with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) using the “willingness to pay” (WTP) approach, the most widely used technique to elicit strengths of individual preferences. This is a secondary analysis of a randomized controlled equivalence trial comparing center-based and home-based pulmonary rehabilitation. At their final session, participants were asked to nominate the maximum that they would be willing to pay to undertake home-based pulmonary rehabilitation in preference to a center-based program. Regression analyses were used to investigate relationships between participant features and WTP values. Data were available for 141/163 eligible study participants (mean age 69 [SD 10] years, n = 82 female). In order to undertake home-based pulmonary rehabilitation in preference to a conventional center-based program, participants were willing to pay was mean $AUD176 (SD 255) (median $83 [IQR 0 to 244]). No significant difference for WTP values was observed between groups (p = 0.98). A WTP value above zero was related to home ownership (odds ratio [OR] 2.95, p = 0.02) and worse baseline SF-36 physical component score (OR 0.94, p = 0.02). This preliminary evidence for WTP in the context of pulmonary rehabilitation indicated the need for further exploration of preferences for treatment location in people with COPD to inform new models of service delivery.

Keywords:

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is associated with significant symptom burden for individuals and substantial healthcare costs to society [Citation1]. Benefits attributable to pulmonary rehabilitation completion include improvements in exercise capacity, symptoms and health-related quality of life as well as reductions in healthcare utilization [Citation2,Citation3]. Although pulmonary rehabilitation referral is recommended unequivocally in the management of COPD [Citation1], program access remains a challenge worldwide [Citation4–7]. Beyond determining the clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness of pulmonary rehabilitation, it is important to consider people’s preferences for mode and site of program delivery. Individual factors, such as travel to center-based programs, are crucial in determining uptake and completion [Citation8]. Preferences for treatment location have been described for people with other conditions [Citation9–11] but have not been reported in people with COPD.

The “contingent valuation” method is increasingly used in health economics research in order to attribute a value to services not available in traditional markets. This approach seeks to directly assess an individual’s attribution of value (or “stated preference”) by providing a monetary estimate for the benefit provided by a service/intervention as though a market for it existed [Citation12,Citation13]. According with standard welfare economic theory, willingness to pay (WTP) is the most widely used technique to assess contingent valuation and elicits strengths of preferences by asking a respondent to state the maximum amount they are “willing to pay” to attain a certain health state or access a particular intervention [Citation14,Citation15]. These preferences account for factors specific to the individual that may be otherwise unanticipated, intangible (e.g. pain) or not health-related (e.g. loss of leisure time) [Citation16,Citation17]. However, there are specific methodological factors to consider in order to ensure useful application to healthcare decision-making, particularly in the presentation of the WTP question. A payment scale format presents a specified range of monetary values and asks respondents to select a value that best represents the amount they would be “willing to pay” for a specified benefit [Citation18]. There has been limited application of this approach to medication [Citation19] and a hypothetical cure [Citation17,Citation20] for people with COPD. The aims of this study were: to describe the WTP values that participants attributed to the opportunity to undertake home-based instead of center-based pulmonary rehabilitation; to explore whether WTP values differed between home and center-based groups; and to investigate the relationships between WTP values and socioeconomic factors as well as clinical variables.

Methods

Study design and setting

This study was conducted alongside an equivalence RCT completed at two tertiary metropolitan public hospitals. The protocol [Citation21], CONSORT statement and clinical outcomes [Citation22] have been published (Trial registration number NCT01423227, clinicaltrials.gov). Before data collection began, institutional ethics approvals were received and all participants provided written informed consent.

Participants and intervention

In brief, 166 participants with stable COPD [Citation1] were recruited on referral to pulmonary rehabilitation and randomly assigned (1:1) to participate in home-based or center-based programs. All participants underwent exercise training and self-management education. The home-based program commenced with a home visit by a physiotherapist to establish exercise goals and supervise the first exercise session. This was followed by seven once-weekly telephone calls from a physiotherapist, using structured modules delivered within a motivational interviewing framework [Citation21]. Center-based participants attended an 8-week, twice-weekly outpatient group-based supervised program [Citation23].

Data collection

Demographic and clinical information, including functional exercise capacity (distance walked on 6-minute walk test, 6MWD) [Citation24], disease-specific health-related quality of life (dyspnea domain of the Chronic Respiratory Disease Questionnaire, CRQ-D) [Citation25] and generic health-related quality of life physical and mental component scores (Medical Outcomes Survey Short-form 36, SF-36) [Citation26] were collected prior to pulmonary rehabilitation (baseline) and following program completion (end-rehabilitation). Prior to end-rehabilitation assessment of 6MWD, participants were asked to rate their walking ability on a global rating of change scale in response to the question “Has there been any change in your walking ability since you started the pulmonary rehabilitation program?” [Citation27]. Expected benefits of pulmonary rehabilitation include both an improvement in exercise capacity and reduction in dyspnea. Response to pulmonary rehabilitation was therefore defined in two ways; achieving the minimal important difference (MID) in 6MWD (25-meter improvement) [Citation28] and CRQ-D (2.5-point improvement) [Citation29]. At their final pulmonary rehabilitation session, participants were asked about socioeconomic factors: weekly household income ($); receipt of government pension; home ownership (yes/no); and highest level of education (did not complete high school, completed high school, higher education or training). Postcode of residence was sourced from contact details to enable classification according to quartiles of the Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantage [Citation30]. Participants were asked to nominate the maximum amount of money that they would be willing to pay to be able to undertake home-based pulmonary rehabilitation in preference to a conventional center-based program. If unable to nominate a value, a payment scale was used to help identify a threshold (Appendix).

Statistical analysis

Summary statistics for continuous variables were reported as mean (SD) or median [IQR] and range of nominated values where applicable. Categorical variables were presented by total number and as a group proportion (%). Between-group differences compared using independent samples t-test or the Mann-Whitney U test as appropriate. Between-group differences for categorical variables were assessed using Chi2 test. All costs were in 2017 Australian dollars. The difference in WTP values between intervention groups was assessed using bootstrapped t-tests (1000 samples) [Citation31]. To identify candidate predictor variables for WTP values, the relationships between WTP values and continuous variables were determined using Pearson’s or Spearman’s correlation coefficient as appropriate. The relationships between continuous and categorical variables (two categories of response to WTP: 0 = zero, 1 = non-zero) were determined using Kendall’s correlation coefficient [Citation32]. Predictor values were identified for linear regression (WTP value) and logistic regression (nomination of a “zero” response to WTP) controlling for weekly household income (threshold p < 0.1). Data were analyzed using SPSS (v26.0, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). α was set at 0.05.

Results

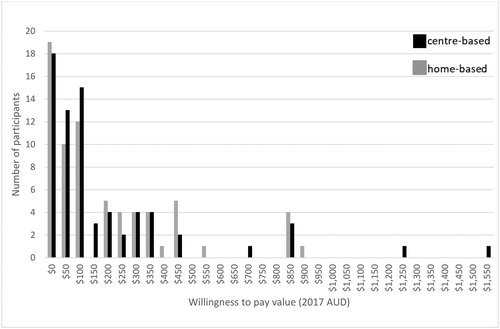

From 166 participants in the clinical trial, 141 (85%) provided a response for WTP (n = 70 home-based, n = 71 center-based). Features of participants who did (n = 141) and did not (n = 23) provide a WTP value are presented in . No significant differences between participants who did and did not provide WTP values were demonstrated for any outcome at end-rehabilitation including global rating of change scores. The amount that participants were willing to pay to be able to undertake home-based pulmonary rehabilitation in preference to a conventional center-based program was mean $176 (SD 255) (median $83 [IQR 0 to 244]). No significant difference between the home-based (mean $175 [SD 283], median $100 [0 to 254]) and center-based (mean $176 [SD 226], median $83 [IQR 5 to 203]) groups; p = 0.98) was demonstrated. The frequency distribution of WTP values expressed by participants in both groups is presented in .

Table 1. Descriptive participant features and candidate predictor variables for response to willingness to pay.

From the range of candidate predictor variables, weak correlations with WTP were evident for age and baseline SF-36 physical component score (). Linear regression did not identify any significant associations ().

Table 2. Candidate demographic, clinical and socioeconomic predictor variables associated with willingness to pay values and expression of a “non-zero” willingness to pay response.

Table 3. Multiple regression for variables associated with willingness to pay values.

Of participants who provided WTP responses, 36 (26%) nominated “zero” values, with no significant difference between intervention groups (home-based 19/70 [27%], center-based 17/71 [26%]; p = 0.66). From the range of candidate predictor variables for nominating “zero” values, weak correlations with WTP were evident for home ownership and baseline SF-36 physical component score ().

Proportionally more people who did not own their home nominated a “zero” value (20/51 [39%]) compared to home owners (16/81 [20%]; p = 0.01). Logistic regression identified an odds ratio (OR) of 2.95 (p = 0.02) for people who owned their home being more likely to express a WTP value above “zero” (). Additionally, people with better baseline SF-36 physical component score were less likely to express a WTP value above “zero” (OR 0.94, p = 0.02).

Table 4. Logistic regression for variables associated with expression of a “non-zero” willingness to pay response.

Discussion

This is the first application of WTP for treatment location in people with COPD undertaking pulmonary rehabilitation. In order to capture the true value of interventions, participant preferences for program features should be considered in service evaluations to ensure adequately informed policy decisions [Citation33]. A recent systematic review showed that satisfaction with non-health aspects of care is independent of health-related outcomes [Citation34] and revealed a clear preference for home-based treatment compared to clinical settings, relating to ease of access to intervention across a range of disease areas and various aspects of healthcare [Citation9–11]. For people with COPD, examination of preferences for treatment location (home vs. hospital) during an exacerbation requiring inpatient care revealed that some respondents had fixed preferences for either option [Citation35,Citation36]. This suggested in the presence of clinical and cost equivalence, treatment location options should be available [Citation35]. Previous work evaluating home and center-based pulmonary rehabilitation has demonstrated equivalence in clinical outcomes [Citation22] and cost-effectiveness [Citation37]. This WTP analysis complements previous work by eliciting the participants’ own valuation (or preferences) for access to a home-based program, information that is not captured in economic evaluations which do not incorporate non-health attributes [Citation38,Citation39].

Nominating a monetary value for healthcare is challenging, particularly in a country with publicly funded outpatient services such as Australia. Most consumers were not be familiar with purchasing access to healthcare programs, which could have led to understatement of WTP due to the perception that these services should be free to access [Citation13]. This leads to difficulties with managing “zero” values that may actually be “protest” votes or reflect an individual’s capacity to pay. Consideration for the framing effects in eliciting WTP valuation is very important, due to potential for response bias [Citation40]. A detailed payment scale design with a realistic range may help respondents to elicit values closer to their “true” WTP values, and hence produce higher-quality outcomes, through avoiding starting point bias inherent to other formats [Citation18,Citation41,Citation42]. It is also important to ensure that participants have a concrete understanding of the representative scenario [Citation39].

The response rate in this study was comparable to or better than of previous studies [Citation11,Citation19,Citation20]. The skewed distribution of WTP values was anticipated, with a large number of “zero” values and a high degree of heterogeneity in elicited responses [Citation43]. The absence of a strong relationship with sociodemographic variables and lack of explanatory power of the regression model is common to other studies [Citation17,Citation44]. Interestingly, previous studies looking at WTP values in people with COPD found an association with increased disease severity [Citation19,Citation20], which may be attributable to the different contexts and benefits. This study did demonstrate a relationship between the value attributed to a home-based program and poorer baseline physical function. Home ownership had the strongest relationship with expression of a WTP above zero, with home owners being nearly three times more likely to express a WTP value. Although an association between weekly household income and WTP was not demonstrated [Citation13], home ownership does represent an individual’s financial status and therefore may reflect the validity of the WTP results in accordance with economic theory [Citation45].

As WTP is a hypothetical concept, there is a risk of overstatement of WTP as no “real” payment is required [Citation17]. In this study, the magnitude of the expressed WTP value did not differ between intervention groups, despite lack of direct experience of the alternative. Although no relationship with group allocation was found for expression of a “zero” value or for nominated WTP values, it is possible that the preferences of treatment naïve participants may be different. This is a potentially important consideration in COPD, where patients may repeat rehabilitation programs many times over the years [Citation46]. This study was part of an RCT comparing clinical outcomes of a home and center-based program; it was powered to demonstrate clinical equivalence not for participant preferences. People with a strong preference for the center-based program did not consent to participation; therefore, these participants may be more positively disposed toward the home-based option. However, this pragmatic study reflected “real world” practice, and the participants were likely to be representative of many people referred to pulmonary rehabilitation.

Conclusions

The economic evaluation of health care interventions is an integral component of resource allocation. However, the value people place on their care is another important consideration in aligning models of service provision with the optimization of their health status and function [Citation33,Citation46] but research on participant preferences for health care interventions remains uncommon.

Despite recommendations that both health and non-health benefits be assessed when evaluating the value of complex health interventions [Citation47], the potential value of the WTP method to assess specific treatments for COPD is still undeveloped [Citation17]. There is scope for future work to elaborate on these findings for participant preference for location of pulmonary rehabilitation in people with COPD.

Acknowledgments

Institutional ethics approvals were received and all participants provided written informed consent before data collection began.

Declaration of interest

C.F.M. has directed speaker’s fees from Menarini and Astra Zeneca to her institution and received in kind support from Air Liquide (unrelated work). The other authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Data availability statement

Requests for data sharing should be directed to A.E.H., who is the custodian of the complete set of data encompassing this study.

References

- Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD [Internet]. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; 2020 [cited 2020 Aug 31]. Available from: https://goldcopd.org/.

- McCarthy B, Casey D, Devane D, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2:CD003793.

- Puhan M, Gimeno-Santos E, Cates C, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation following exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;12:CD005305.

- Camp P, Hernandez P, Bourbeau J, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation in Canada: a report from the Canadian Thoracic Society COPD Clinical Assembly. Canadian Respir J. 2015;22(3):147–152.

- Levack W, Weatherall M, Reeve J, et al. Uptake of pulmonary rehabilitation in New Zealand by people with COPD in 2009. NZ Med J. 2012;125:1–11.

- Marks G, Reddel H, Guevara-Rattray E, et al. Monitoring pulmonary rehabilitation and long-term oxygen therapy for people with COPD in Australia: a discussion paper. Canberra (Australia): Australian Institute for Health and Welfare; 2013 [cited 2020 Aug 31]. Available from: https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-778647592/view.

- Desveaux L, Janaudis-Ferreira T, Goldstein R, et al. An international comparison of pulmonary rehabilitation: a systematic review. COPD. 2015;12(2):144–153.

- Keating A, Lee A, Holland A. What prevents people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease from attending pulmonary rehabilitation? A systematic review. Chron Respir Dis. 2011;8(2):89–99.

- Coley C, Li Y, Medsger A, et al. Preferences for home vs hospital care among low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(14):1565–1571.

- Marra C, Frighetto L, Goodfellow A, et al. Willingness to pay to assess patient preferences for therapy in a Canadian setting. BMC Health Serv Res. 2005;5(1):43.

- Whitty J, Stewart S, Carrington M, et al. Patient preferences and willingness-to-pay for a home or clinic based program of chronic heart failure management: findings from WHICH? trial. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e58347.

- Bala M, Mauskopf J, Wood L. Willingness to pay as a measure of health benefits. Pharmacoeconomics. 1999;1:9–18.

- Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Claxton K, et al. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. 4th ed. New York (NY): Oxford University Press; 2015.

- Bergmo T, Wangberg S. Patients’ willingness to pay for electronic communication with their general practitioner. Eur J Health Econ. 2007;8(2):105–110.

- Hammitt J. QALYs versus WTP. Risk Anal. 2002;22(5):985–1001. DOI:10.1111/1539-6924.00265

- Bayoumi A. The measurement of contingent valuation for health economics. Pharmacoeconomics. 2004;22:691–700.

- Stavem K. Association of willingness to pay with severity of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, health status and other preference measures. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2002;6(6):542–549.

- Soeteman L, van Exel J, Bobinac A. The impact of the design of payment scales on the willingness to pay for health gains. Eur J Health Econ. 2017;18(6):743–760.

- Kawata A, Kleinman L, Harding G, et al. Evaluation of patient preference and willingness to pay for attributes of maintenance medication for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Patient. 2014;7(4):413–426.

- Chen Y, Ying Y, Chang K, et al. Study of patients’ willingness to pay for a cure of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Taiwan. IJERPH. 2016;13(3):273.

- Holland AE, Mahal A, Hill C, et al. Patient preference and satisfaction in hospital-at-home and usual hospital care for COPD exacerbations: Results of a randomised controlled trial. BMC Pulm Med. 2013;13:57.

- Holland AE, Mahal A, Hill C, et al. Home-based rehabilitation for COPD using minimal resources: a randomised, controlled equivalence trial. Thorax. 2017;72:57–65.

- Spruit M, Singh S, Garvey C, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Statement: key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(8):e13–1027.

- Holland A, Spruit M, Troosters T, et al. An official European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society technical standard: field walking tests in chronic respiratory disease. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(6):1428–1446.

- Williams J, Singh S, Sewell L, et al. Development of a self-reported Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire (CRQ-SR). Thorax. 2001;56(12):954–959.

- Hajiro T, Nishimura K, Tsukino M, et al. A comparison of the level of dyspnoea vs disease severity in indicating the health-related quality of life of patients with COPD. Chest. 1999;116(6):1632–1637.

- Jaeschke R, Singer J, Guyatt GH. Measurement of health status: ascertaining the minimal clinically important difference. Control Clin Trials. 1989;10(4):407–415.

- Holland A, Hill C, Rasekaba T, et al. Updating the minimal important difference for six-minute walk distance in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91(2):221–225.

- Schunemann HJ, Puhan M, Goldstein R, et al. Measurement properties and interpretability of the Chronic Respiratory Disease Questionnaire (CRQ). COPD. 2005;2(1):81–89.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Census of Population and Housing: Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA). Canberra (Australia): Australian Government; 2011 [released 2013 Mar 28].

- Mihaylova B, Briggs A, O’Hagan A, et al. Review of statistical methods for analysing healthcare resources and costs. Health Econ. 2011;20(8):897–916.

- Field A. Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. 4th ed. London (UK): SAGE Publishing; 2014.

- Sturm R. Economics and physical activity. A research agenda. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28(2):141–149.

- Higgins A, Barnett J, Meads C, et al. Does convenience matter in health care delivery? A systematic review of convenience-based aspects of process utility. Value Health. 2014;17(8):877–887.

- Goossens L, Utens C, Smeenk F, et al. Should I stay or should I go home? A latent class analysis of a discrete choice experiment on hospital-at-home. Value Health. 2014;17(5):588–596.

- Utens C, Goossens L, van Schayck O, et al. Patient preference and satisfaction in hospital-at-home and usual hospital care for COPD exacerbations: Results of a randomised controlled trial. Int J Nursing Studies. 2013;50(11):1537–1549.

- Burge AT, Holland AE, McDonald CF, et al. Home-based pulmonary rehabilitation for COPD using minimal resources: an economic analysis. Respirology. 2020;25:183–190.

- Tinelli M, Ryan M, Bond C. What, who and when? Incorporating a discrete choice experiment into an economic evaluation. Health Econ Rev. 2016;6(1):31.

- Rome A, Persson U, Ekdahl C, et al. Willingness to pay for health improvements of physical activity on prescription. Scand J Public Health. 2010;38(2):151–159.

- Gyrd-Hansen D, Jensen M, Kjaer T. Framing the willingness-to-pay question: impact on response patterns and mean willingness to pay. Health Econ. 2014;23(5):550–563.

- Donaldson C, Thomas R, Torgerson D. Validity of open-ended and payment scale approaches to eliciting willingness to pay. Appl Econ. 1997;29(1):79–84.

- Whynes D, Philips Z, Frew E. Think of a number… any number? Health Econ. 2005;14(11):1191–1195. DOI:10.1002/hec.1001

- Gyrd-Hansen D, Kjaer T. Disentangling WTP per QALY data: different analytical approaches, different answers. Health Econ. 2012;21(3):222–237.

- O’Brien B, Viramontes JL. Willingness to pay: a valid and reliable measure of health state preference? Med Decis Making. 1994;14(3):289–297.

- Persson U, Norinder A, Hjalte K, et al. The value of a statistical life in transport: findings from a new contingent valuation study in Sweden. J Risk Uncertainty. 2001;23(2):121–134.

- Heng H, Lee A, Holland A. Repeating pulmonary rehabilitation: prevalence, predictors and outcomes. Respirology. 2014;19(7):999–1005.

- Payne K, McAllister M, Davies L. Valuing the economic benefits of complex interventions: when maximising health is not sufficient. Health Econ. 2013;22(3):258–271.

Appendix

In Australia, pulmonary rehabilitation is usually offered at a hospital or health center, not at home. Attending pulmonary rehabilitation in the public health system is generally free of charge.

If there was an option to do Pulmonary Rehabilitation in your own home, how much would you be willing to pay for this?

I would be prepared to pay $_______ to have pulmonary rehabilitation at home.

If the participant is unable to specify an amount, give one of the following options and ask:

Would the maximum amount you are willing to pay be higher or lower than $X?

Keep giving options according to the response, until a figure can be arrived at.

Options:

$1500

$100

$500

$250

$100