Abstract

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) for COPD have been much debated. Our aim was to investigate characteristics of ICS prescribed COPD patients managed only in general practice compared to those also managed in secondary care. Participating general practitioners recruited patients with COPD (ICPC 2nd ed. code R95) currently prescribed ICS (ACT code R03AK and R03BA). Data on demographics, comorbidities, smoking habits, spirometry, dyspnea score and exacerbation history were retrieved from medical records. Logistic regression analysis was applied to detect predictors associated with management in secondary care. 2,279 COPD patients (45% males and mean age 71 years) were recruited in primary care. Compared to patients managed in primary care only (n = 1,179), patients also managed in secondary care (n = 560) were younger (p = 0.013), had lower BMI, more life-time tobacco exposure (p = 0.03), more exacerbations (p < 0.001) and hospitalizations (p < 0.001) and lower FEV1/FVC-ratio (0.59 versus 0.52, respectively). Compared to patients managed in only primary care, logistic regression analysis revealed that management also in secondary care was associated to MRC-score ≥3 (OR 2.70; 95% CI 1.50–4.86; p = 0.001), FEV1%pred (OR 0.98; 95% CI 0.95 to 0.99; p = 0.036), and systemic corticosteroids for COPD exacerbation (OR 1.44; 95% CI 1.10–1.89; p = 0.008). In COPD patients prescribed ICS recruited in primary care, patients also managed in secondary care had more respiratory symptoms, lower lung function and exacerbations treated with systemic corticosteroids indicating that the most severe COPD patients, in general, are referred for specialist care.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a leading cause of mortality and morbidity world-wide and characterized by airflow limitation and persistent respiratory symptoms due to airway abnormalities usually caused by exposure to noxious gases and/or particles [Citation1]. COPD exacerbations are defined by the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) as an acute worsening of respiratory symptoms that leads to additional treatment [Citation1]. COPD usually entails progressive excess decline in lung function, in some cases even after smoking cessation [Citation1–3].

The overall aim of the GOLD strategy document is to facilitate best possible management of COPD patients [Citation4]. However, a previous study investigating adherence to GOLD strategy document found that 44% of COPD patients could be regarded as undertreated, while almost one-fourth received treatment inconsistent with recommendations [Citation5]. Low adherence to recommended treatment has also been reported in a recent multicenter observational study, which found that more than 65% of group B patients received LABA/ICS (long-acting β2-agonst in combination with inhaled corticosteroid) [Citation6]. In many countries, including Denmark, COPD is usually managed in primary care, while chronic care of severe COPD is provided in secondary care by specialists in respiratory medicine [Citation7–11]. Appropriate management of COPD patients may sometimes vary depending on whether patients are followed by a respiratory specialist or non-respiratory specialist, including general practitioners (GPs) [Citation12–16]. Multiple causes for poor adherence to strategy document in COPD management in primary care have been suggested including short consultation time and physician’s disagreement with strategy document [Citation8, Citation9, Citation17–19]. While it is fundamental to follow a stepwise approach as recommended by GOLD, only 35% of GPs choose a long-acting bronchodilator, which is considered the primary COPD maintenance treatment, when COPD patients have insufficient symptom relief on short-acting bronchodilators as needed [Citation14]. Studies also indicate that spirometry is poorly utilized in primary care even though most COPD patients are managed by their respective GP [Citation13, Citation20–22]. Furthermore, findings of previous studies underline the difference in management of COPD between primary and secondary care and reveal that specialist respiratory physicians are more likely to adhere to recommended interventions regarding treatment than non-respiratory physicians [Citation23–25]. We, therefore, hypothesized that certain characteristics determine referral to secondary care for further disease management in ICS prescribed COPD patients managed in primary care.

The aim of this study was to examine whether COPD patients currently prescribed ICS managed in primary care are referred to secondary care for further management in accordance with current recommendations based on patient characteristics.

Methods

Study cohort and patient selection

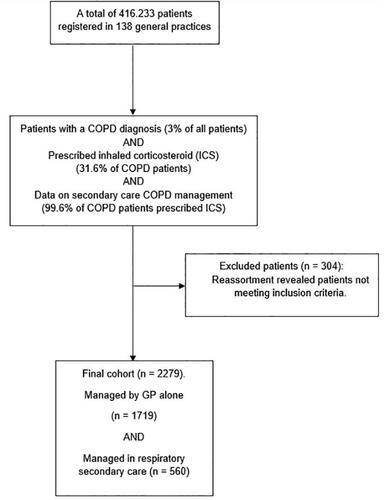

Eligible patients had been diagnosed with COPD by their respective GPs and were currently on ICS treatment (coded as International Classification of Primary Care, 2nd ed. code R95 in electronic patient journals and the ACT code R03AK and R03BA, specifying ICS therapy). Participating GPs performed searches in their designated Electronic Patient Journal (EPJ) system for the codes indicating COPD and current ICS treatment. Some patients were only managed by their GP, that is in general practice only, while other patients were also managed by respiratory specialists in outpatient clinics. The selection process of patients participating in the study is summarized in , also demonstrating the focus of the present study. Further details of the recruitment process have been published previously [Citation26]. Participating GPs included in the final analysis (n = 138) provided relevant data, if available, on demographics, clinical characteristics, blood-eosinophils, pharmacological treatment, hospital admissions for COPD, previous COPD exacerbations, smoking status, comorbidities, and duration of COPD for all enrolled patients. Among all patients fulfilling criteria for inclusion, every general practice enrolled up to a maximum of twenty randomly selected patients. If less than twenty patients were identified, data were registered for all patients. All patients were given a unique project ID number to guarantee anonymity with only the specified GP being unblinded.

Statistical analysis

Data are reported as mean values ± one standard deviation (SD). Categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages. Clinical variables and characteristics of patients managed by GPs in general practice only were compared to patients also managed by respiratory physicians in secondary care using independent sample t-test for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorial variables. Characteristics of possible clinical relevance in included COPD patients associated with management in secondary care was assessed by logistic regression and reported as an odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed using the statistical program IBM SPSS version 25 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) and transferred to Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) spreadsheet for figure development.

Results

Of the COPD patients currently on ICS therapy recruited in primary care for the present study (n = 2,279), 560 (24.6%) were also managed in secondary care, that is followed in a respiratory outpatient clinic. Further details and baseline characteristics of the patients are given in .

Table 1. Characteristics of enrolled patients (n = 2,279) with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and currently prescribed inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) according to whether patients were managed in secondary care by a respiratory specialist or only in primary care by a general practitioner (GP).

Lung function

COPD patients on ICS managed in secondary care had lower FEV1/FVC ratio (mean 0.52 (SD 0.15)) compared to those managed only in primary care (mean 0.59 (SD 0.14)) (p < 0.001). More information is outlined in .

GOLD classification

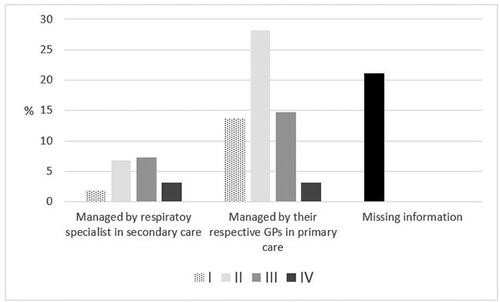

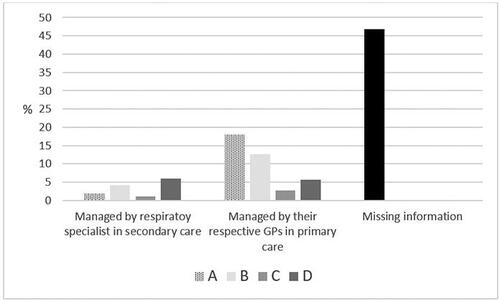

Distribution of airflow limitation and severity classification, based on symptoms and exacerbation history according to GOLD, in patients managed in primary care compared to secondary care is presented in and , signifying a difference between the two groups for both severity classification and airflow limitation.

Comorbidities

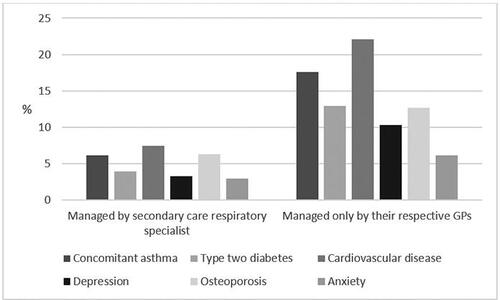

The most prevalent comorbidities for both groups were cardiovascular disease (22.1% and 7.4%, respectively, for primary care only and secondary care) and concomitant asthma (17.6% for primary care and 6.1% for secondary care). Looking at both groups individually, 29.3% of COPD patients followed in primary care alone had cardiovascular disease, while 30.2% of patients also followed in secondary care had cardiovascular disease. More details on comorbidities are provided in .

Exacerbation history

In the previous year, ICS prescribed COPD patients managed in secondary care had overall slightly more hospitalizations due to exacerbations (7.5%) than patients managed in primary care alone (6.9%). Looking at both groups individually, 61.4% of patients managed in secondary care had exacerbations and 30.6% had hospitalizations due to exacerbation. In comparison, 38.6% of patients managed in primary care alone had exacerbations and 9.3% had hospitalizations due to exacerbation. More details are outlined in .

Table 2. Hospitalization admission due to exacerbation, treatment with corticosteroid and antibiotics in ICS prescribed COPD patients managed by their respective general practitioner and, for some, also managed in an outpatient clinic in secondary care.

Predictors of secondary care management

Logistic regression analysis indicated that ICS prescribed COPD patients with an MRC-score three or more were almost three times as likely to be managed in secondary care than in primary care (OR 2.70; CI 1.50–4.86; p = 0.001). In addition, patients managed in secondary care were more likely to be treated with rescue courses of corticosteroids due to COPD exacerbation (OR 1.44; CI 1.10–1.89; p = 0.008). Details are provided in .

Table 3. Characteristics of clinical relevance in included COPD patients associated with management in secondary care (n = 560) assessed by logistic regression and reported as an odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Discussion

The present study of ICS prescribed COPD patients in primary care showed that predictors for referral to secondary care outpatient respiratory clinics for further management were more dyspnea, lower lung function, and higher risk of steroid treatment due to COPD exacerbation.

A study found that COPD patients followed by their respective GP had more control visits per year than those controlled by pneumologist suggesting a diversity in clinical follow-up and management of COPD patients between secondary and primary care [Citation27]. In line with this, our study similarly found that COPD patients attending their GPs had an annual control visit in 54% of cases of those managed in primary care in the previous year, while only 39% of cases of those managed in secondary care had an annual control visit in the previous year.

Previous studies report on reasons for misdiagnosis and misclassification of COPD in primary care including lack of adherence to use of spirometry [Citation21, Citation28–30]. Our study accordingly found that of those with information on verification of COPD diagnosis with spirometry 15% of cases of COPD patients managed in primary care had not undergone spirometry to confirm diagnosis. It has previously been suggested that an educational program in general practice significantly improves adherence to use of spirometry and could potentially reduce risk of misdiagnosis [Citation31].

Compared to a previous study, which found that a diagnosis of COPD was associated with a greater risk of anxiety (OR 1.85) [Citation32], our study found that patients had more than 2 times the odds of having a doctor’s diagnosis of anxiety when managed in secondary care compared to primary care. This study also found that a diagnosis of anxiety in COPD patients was related to higher risk of exacerbation [Citation32]. These findings are similar to those presented in this study, which indicate that patients managed in secondary care with higher risk of anxiety usually also have a higher MRC-score, worse lung function and higher risk of exacerbations as well as hospitalizations compared to patients managed in primary care. According to previous studies both anxiety and depression occur rather commonly among COPD patients [Citation33, Citation34] and are increasingly acknowledged as risk factors for impaired quality of life and morbidity in COPD patients [Citation35]. In general, COPD patients with three or more comorbidities, such as anxiety and depression, but also including cardiovascular disease and concomitant asthma, which were the most prevalent in the current study, have higher mortality and risk of hospitalization compared to those with fewer comorbidities [Citation36].

Another study from the UK concluded that almost 60% of COPD patients were prescribed inhaled medications in accordance with GOLD strategy document [Citation37]. However, numerous studies have reported overprescribing of ICS in COPD [Citation6, Citation13, Citation26, Citation31, Citation38] with our study being no exception as we found that COPD patients in GOLD groups A and B in both primary and secondary care were treated with ICS independent of GOLD strategy document ().

A few strengths of the current study are worth mentioning. First, to our knowledge no other cross-sectional population-based study has previously presented differences in characteristics in as many COPD patients in primary care compared to secondary care. Additionally, our study has presented significant findings, which further strengthen and elaborate the findings of previous studies researching outcomes and differences in subgroups of COPD patients, and hopefully underline the need for improvement in the management of COPD patients, perhaps through implementation of self-management plans and educational activities, which have revealed overall promising results especially for patient’s satisfaction to services of health care providers [Citation39, Citation40]. Certain weaknesses in the current study should be emphasized. We had, unfortunately, missing values for some variables as almost one-fifth of COPD patients only followed in primary care and almost one-fourth of COPD patients also followed in secondary care had missing values on spirometry use for diagnosis verification. Furthermore, our study was dependent on data from electronic patient journals (EPJ’s) from general practice. EPJ’s contain both data provided by general practitioners and, for patients also followed in secondary care, also data provided by physicians in outpatient clinics. Some of the significant associations between the two subgroups of patients (i.e. ICS prescribed COPD patients followed in primary care versus secondary care) could be assigned to the lack of data from respiratory outpatient clinics being sent back to general practice once patients have had a doctor’s visit in secondary care. As an example, approximately 60% of patients followed in primary care alone had both data registered on GOLD classification I-IV () and FEV1. Of patients also followed in secondary care, 21% of patients had data on FEV1 registered, but only 5.5% had data on GOLD I-IV classification. Another limitation, which could have interfered with results and perhaps over- or underestimated prevalence of ICS prescribed COPD patients in both subgroups, might be attributed to whether patients were managed in primary care alone or for some in secondary care at the time of data collection. It is plausible that at the time of data collection some patients classified as having less severe disease were followed in secondary care while other patients classified with more severe disease in primary care had not yet been referred to secondary care outpatient clinics. In keeping with this, our results indicated that a small proportion of patients classified as GOLD groups A and B were followed in secondary outpatient clinics for adequate disease management, perhaps due to recent exacerbation(s), and GOLD classification was hence not reassessed (). Nevertheless, our findings indicated a high prevalence of ICS overprescription in COPD patients, which is unlikely linked to the cross-sectional design of this study but rather discordance with applicable GOLD strategy document.

Our findings suggest that ICS prescribed COPD patients with more severe disease usually are referred to secondary care for further management, which is in accordance with GOLD strategy document. However, there is a need for further research to elaborate accurate treatment control and diagnosis of ICS prescribed COPD patients with the hopes of gaining a better understanding and reduce risk of overtreatment, overdiagnosis, and burden of COPD.

Declarations

The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency. The present study was a non-interventional study, and it was not mandatory to acquire approval from the Ethical Committee and the Danish Medicines Agency. However, they were provided with full study information.

The study was given a neutral recommendation by the committee of multi practice studies in General Practice (MPU10-2017).

Author contributions

OS drafted the first version of the manuscript. CSU is the guarantor of this study. All authors contributed to drafting and revising the manuscript, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Declaration of interest

OS has received fee for drafting the manuscript (as part of his candidate thesis at the University of Copenhagen) and NSG, TS, CJ and CSU as members of the steering committee of the study from Boehringer-Ingelheim, Denmark. The authors declare that they have no other potential conflicts of interest.

Data availability statement

The database will, upon request, be available from the corresponding author according to current legislation.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). 2020. Report. Available from: https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/GOLD-2020-REPORT-ver1.0wms.pdf

- Willemse BW, ten Hacken NH, Rutgers B, et al. Effect of 1-year smoking cessation on airway inflammation in COPD and asymptomatic smokers. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(5):835–845. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.05.00108904

- Gamble E, Grootendorst DC, Hattotuwa K, et al. Airway mucosal inflammation in COPD is similar in smokers and ex-smokers: a pooled analysis. Eur Respir J. 2007;30(3):467–471. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00013006

- Soriano J, Aa A, Kh A, et al. Global, regional, and national deaths, prevalence, disability-adjusted life years, and years lived with disability for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5(9):691–706. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30293-X

- Foda HD, Brehm A, Goldsteen K, et al. Inverse relationship between nonadherence to original GOLD treatment guidelines and exacerbations of COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:209–214. DOI:https://doi.org/10.2147/copd.S119507

- Chan KP, Ko FW, Chan HS, et al. Adherence to a COPD treatment guideline among patients in Hong Kong. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:3371–3379. DOI:https://doi.org/10.2147/copd.S147070

- Seemungal TA, Donaldson GC, Paul EA, et al. Effect of exacerbation on quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157(5):1418–1422. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.157.5.9709032

- Donaldson GC, Seemungal TA, Bhowmik A, et al. Relationship between exacerbation frequency and lung function decline in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2002;57(10):847–852. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1136/thorax.57.10.847

- Anzueto A, Leimer I, Kesten S. Impact of frequency of COPD exacerbations on pulmonary function, health status and clinical outcomes. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2009;4:245–251. DOI:https://doi.org/10.2147/copd.s4862

- Nici L, ZuWallack R. An official American Thoracic Society Workshop report: the integrated care of the COPD patient. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2012;9(1):9–18. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1513/pats.201201-014ST

- Chatila WM, Thomashow BM, Minai OA, et al. Comorbidities in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5(4):549–555. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1513/pats.200709-148ET

- Sundh J, Osterlund Efraimsson E, Janson C, et al. Management of COPD exacerbations in primary care: a clinical cohort study. Prim Care Respir J. 2013;22(4):393–399. DOI:https://doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2013.00087

- Bourbeau J, Sebaldt RJ, Day A, et al. Practice patterns in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in primary practice: the CAGE study. Can Respir J. 2008;15(1):13–19. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1155/2008/173904

- Foster JA, Yawn BP, Maziar A, et al. Enhancing COPD management in primary care settings. MedGenMed. 2007;9(3):24.

- Sehl J, O’Doherty J, O’Connor R, et al. Adherence to COPD management guidelines in general practice? A review of the literature. Ir J Med Sci. 2018;187(2):403–407. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-017-1651-7

- Albitar HAH, Iyer VN. Adherence to global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease guidelines in the real world: current understanding, barriers, and solutions. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2020;26(2):149–154. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1097/mcp.0000000000000655

- Irving G, Neves AL, Dambha-Miller H, et al. International variations in primary care physician consultation time: a systematic review of 67 countries. BMJ Open. 2017;7(10):e017902. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017902

- Jenkins CR, Jones PW, Calverley PM, et al. Efficacy of salmeterol/fluticasone propionate by GOLD stage of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: analysis from the randomised, placebo-controlled TORCH study. Respir Res. 2009;10(1):59. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/1465-9921-10-59

- Make B, Dutro MP, Paulose-Ram R, et al. Undertreatment of COPD: a retrospective analysis of US managed care and medicare patients. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2012;7:1–9. DOI:https://doi.org/10.2147/copd.S27032

- Levy ML, Fletcher M, Price DB, et al. International primary care respiratory group (IPCRG) guidelines: diagnosis of respiratory diseases in primary care. Prim Care Respir J. 2006;15(1):20–34. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcrj.2005.10.004

- Miravitlles M, de la Roza C, Naberan K, et al. Use of spirometry and patterns of prescribing in COPD in primary care. Respir Med. 2007;101(8):1753–1760. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2007.02.019

- Arne M, Lisspers K, Ställberg B, et al. How often is diagnosis of COPD confirmed with spirometry? Respir Med. 2010;104(4):550–556. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2009.10.023

- Lodewijckx C, Sermeus W, Vanhaecht K, et al. Inhospital management of COPD exacerbations: a systematic review of the literature with regard to adherence to international guidelines. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15(6):1101–1110. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01305.x

- Chang CL, Sullivan GD, Karalus NC, et al. Audit of acute admissions of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: inpatient management and outcome. Intern Med J. 2007;37(4):236–241. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-5994.2006.01283.x

- Kelly MG, Elborn JS. Admissions with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease after publication of national guidelines. Ir J Med Sci. 2002;171(1):16–19. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03168933

- Savran O, Godtfredsen N, Sorensen T, et al. COPD patients prescribed inhaled corticosteroid in general practice: based on disease characteristics according to guidelines?Chron Respir Dis. 2019;16:1479973119867949. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/1479973119867949

- Garcia-Aymerich J, Escarrabill J, Marrades RM, et al. Differences in COPD care among doctors who control the disease: general practitioner vs. pneumologist. Respir Med. 2006;100(2):332–339. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2005.04.021

- Strong M, Green A, Goyder E, et al. Accuracy of diagnosis and classification of COPD in primary and specialist nurse-led respiratory care in rotherham, UK: a cross-sectional study. Prim Care Respir J. 2014;23(1):67–73. DOI:https://doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2014.00005

- Lee TA, Bartle B, Weiss KB. Spirometry use in clinical practice following diagnosis of COPD. Chest. 2006;129(6):1509–1515. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.129.6.1509

- Heffler E, Crimi C, Mancuso S, et al. Misdiagnosis of asthma and COPD and underuse of spirometry in primary care unselected patients. Respir Med. 2018;142:48–52. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2018.07.015

- Ulrik CS, Hansen EF, Jensen MS, et al. Management of COPD in general practice in Denmark–participating in an educational program substantially improves adherence to guidelines. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2010;5:73–79.

- Eisner MD, Blanc PD, Yelin EH, et al. Influence of anxiety on health outcomes in COPD. Thorax. 2010;65(3):229–234. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.2009.126201

- Tselebis A, Pachi A, Ilias I, et al. Strategies to improve anxiety and depression in patients with COPD: a mental health perspective. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:297–328. DOI:https://doi.org/10.2147/ndt.S79354

- Savran O, Godtfredsen NS, Sørensen T, et al. Comparison of characteristics between ICS-treated COPD patients and ICS-treated COPD patients with concomitant asthma: a study in primary care. COPD. 2020;15:931–937. DOI:https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S241561

- Yohannes AM, Willgoss TG, Baldwin RC, et al. Depression and anxiety in chronic heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: prevalence, relevance, clinical implications and management principles. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25(12):1209–1221. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.2463

- Sode BF, Dahl M, Nordestgaard BG. Myocardial infarction and other co-morbidities in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a Danish nationwide study of 7.4 million individuals. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(19):2365–2375. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehr338

- White P, Thornton H, Pinnock H, et al. Overtreatment of COPD with inhaled corticosteroids-implications for safety and costs: cross-sectional observational study. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e75221. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0075221

- Ulrik CS, Sørensen TB, Højmark TB, et al. Adherence to COPD guidelines in general practice: impact of an educational programme delivered on location in Danish general practices. Prim Care Respir J. 2012;22(1):23–28. DOI:https://doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2012.00089

- Löfdahl CG, Tilling B, Ekström T, et al. COPD health care in Sweden - a study in primary and secondary care. Respir Med. 2010;104(3):404–411. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2009.10.007

- Khan A, Dickens AP, Adab P, et al. Self-management behaviour and support among primary care COPD patients: cross-sectional analysis of data from the Birmingham chronic obstructive pulmonary disease Cohort. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2017;27(1):46. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-017-0046-6