Abstract

The diagnosis of depression or anxiety is often difficult to establish in patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) as many physical symptoms are shared. There is no consensus on a screening tool for depression and anxiety in patients with COPD. The aim of this systematic review is to review screening tools for depression and anxiety suitable for application among patients with COPD in the clinical setting. A systematic review was made using predefined search terms and eligibility criteria. Of 274 initially screened articles, seven studies were found eligible. Three depression screening tools (BASDEC, BDI-II and HADS-D) had a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity >85%. The best performing anxiety screening tool (GAI) had a sensitivity of 86% and a specificity of 78%. Three screening tools had acceptable psychometric properties according to sensitivity and specificity to detect depression among patients with COPD, but the screening tools for anxiety were of less quality. Further research in and validation of the screening tools is needed to recommend one specific tool.

Introduction

Depression and anxiety are often underdiagnosed and therefore poorly treated in patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) [Citation1]. It is often difficult to establish the diagnosis of these psychiatric comorbidities as many somatic symptoms in COPD such as fatigue, weight loss, shortness of breath and social isolation are also manifestations in depression and anxiety.

Both depression and COPD are highly prevalent conditions. Worldwide, depression is considered the third leading course of disability affecting more than 264 million people and WHO estimates show that 65 million people suffer from moderate or severe COPD [Citation2,Citation3]. The gold standard to establish a depression or anxiety diagnosis is a diagnostic interview performed by a psychiatrist; however, this procedure is impossible to offer to all patients with COPD in clinical practice. Thus, screening tools are necessary in clinical practice to identify the patients in need of treatment or referral to special psychiatric care. Studies suggest considerable variation in the prevalence of depressive symptoms ranging from 17 to 75% among patients with COPD [Citation4,Citation5]. This variability in the estimation of depression in patients with COPD can partly be explained by differences in COPD severity, patient population etc, but also by applying different screening tools.

Hence, knowledge is needed on the best screening tool to screen for depression and anxiety to optimise treatment of patients with COPD.

The aim of this review was to systematically examine screening tools for depression and anxiety and which should be recommended in the clinical setting among patients with COPD.

Methods

Study design

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines from 2009 [Citation6,Citation7].

Eligibility criteria

Studies were considered potentially relevant if they complied with the following inclusion criteria:

Quantitatively examined the prevalence of depression or anxiety in patients with COPD AND

COPD verified by spirometry or by medical record reports AND

depression and/or anxiety screening tools are compared with a diagnostic interview as the gold standard AND

the article is written in English or a Scandinavian language AND

published between the 1 January 2000 and 8 February 2021.

Studies were excluded in accordance with the following exclusion criteria:

patients with terminal illnesses other than COPD such as cancer, chronic heart, liver or kidney failure, ALS etc. OR

patients with COPD with a history of acute exacerbation within the past four weeks.

Information sources

The search strategy was applied to the PubMed, PsycINFO and CINAHL databases. By means of the database search tools, we limited the search to studies published in English or Scandinavian languages in the period from 1 January 2000 and 8 February 2021, when the final search was conducted. Hand-search was performed in the most relevant papers and in relevant previous reviews.

Search strategy

The abovementioned databases were searched using the search string: "(("Depression"[Mesh]) OR ("Anxiety"[Mesh]) OR depress* OR anxiety) AND (("Pulmonary Disease, Chronic Obstructive"[Mesh]) OR COPD OR chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) AND (screen* OR test OR tool) AND (valid* OR psychom* OR accur*)".

Study selection

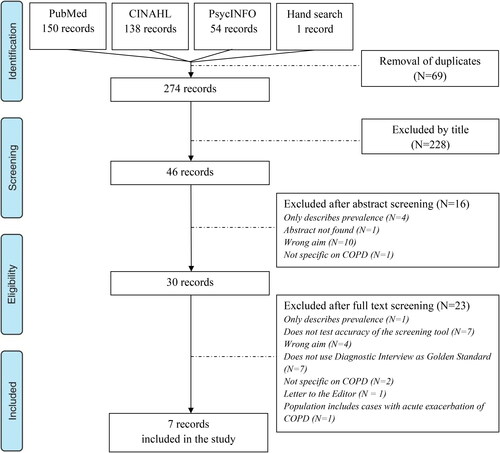

The search results were imported into the citation manager EndNote and duplicates were identified and removed. The extracted studies were examined in a three-stage process by the first author: (1) by title, (2) by abstract and (3) by full text. The first author conducted the selection and in case of any doubt, the last-author evaluated the paper and discussed eligibility until consensus was reached. Studies meeting the eligibility criteria were included in the final analysis.

Data extraction

Data from the included studies on screening tools were extracted and entered into a pre-determined standard form with the following headings: Author, Country of origin, Year of publication, Aim, Study design, Population, Screening tools, Diagnostic interview, Prevalence of anxiety and/or depression and Sensitivity/specificity.

The first author extracted the data. The last author assessed the included papers to check the accuracy of the data extraction process.

Results

The flow chart of the study selection process is presented in . After removal of duplicates in EndNote, a total of 274 results were screened by title. One of the studies, Julian et al. [Citation8], was found by hand-search. A total of 228 studies were excluded by title and 16 were excluded after reading the abstract. Thirty studies were read in full text and seven of these met all of the inclusion criteria and were thus included. Six of them were cross-sectional studies [Citation8–13] and one was a prospective, multi-center cohort study [Citation14]. Relevant data from the included studies are listed in .

Table 1. Overview of data from included studies.

Depression screening tools

Five of the included papers tested depression screening tools among patients with COPD [Citation8–12]. Six different screening tools were tested as one of the studies tested both the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – Depression Subscale (HADS-D) and the Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II) [Citation9]. No screening tools were tested in more than one study. Four different diagnostic interviews were used to test the validity of the screening tools:

Julian et al. [Citation8] evaluated the Geriatric Depression Scale − 15 Items (GDS-15) using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) as the gold standard and found a sensitivity of 81.0% and a specificity of 87.0%.

Phan et al. [Citation9] used the MINI as the gold standard but investigated the validity of the HADS-D and the BDI-II. The researchers modified the HADS-D and after removal of question 4 ("I feel as if I am slowed down") the optimal cut-off score was ≥5 and sensitivity and specificity were 100.0% and 82.6%, respectively detecting all true positives. The researchers also modified the BDI-II by removing question 21 ("Loss of interest in sex"). This modification suggested an optimal cut-off score ≥12, a sensitivity of 100.0% and a specificity of 78.7%. Yohannes et al. [Citation12] used the Geriatric Mental State Schedule (GMS) as the gold standard to validate the Brief Assessment Schedule Depression Cards (BASDEC) and found a sensitivity of 100.0% and a specificity of 93.0% using an optimal cut-off score ≥7.

Stage et al. [Citation11] tested the Six-Item Hamilton Depression Subscale (HDSS) and a sensitivity of 91.0% and a specificity of 88.0% was detected using a cut-off score ≥6.

Finally, Aydin et al. [Citation10] used the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) as the gold standard to evaluate the General Health Questionnaire 12 Items (GHQ-12). Using a cut-off score ≥5 the GHQ-12 yielded a sensitivity of 83.3% and a specificity of 80.0% for both psychiatric comorbidities combined. They did not test sensitivity or specificity for anxiety or depression separately.

Anxiety screening tools

Three of the seven included studies examined the use and validity of anxiety screening tools [Citation9,Citation13,Citation14]. Five different screening tools were tested. All of the screening tools were tested against the MINI as the gold standard.

Cheung et al. [Citation13] examined the validity of the HADS-A and the Geriatric Anxiety Inventory (GAI). The GAI had an optimal cut-off score ≥3 with a sensitivity of 85.7% and a specificity of 78.0%. The HADS-A was shown to have an optimal cut-off score ≥4 yielding a sensitivity of 78.6% and a specificity of 70.7%.

Phan et al. [Citation9] examined the validity of the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) and the HADS-A. For the HADS-A, they found an optimal cut-off score ≥ 9 yielding a sensitivity of 71.4% and a specificity of 85.7%. The BAI had an optimal cut-off score ≥ 12 with a sensitivity of 78.6% and a sensitivity of 76.2%.

Baker et al. [Citation14] tested the validity of the Generalised Anxiety Disorder 7-Item Scale (GAD-7), the Anxiety Inventory for Respiratory Disease (AIR) and the HADS-A. They found a sensitivity of 63% and a specificity of 85% of the HADS-A using a cut-off score ≥7.

Sensitivity was 78.0% and 66.0% and specificity was 77.0% and 65.0% for the GAD-7 and the AIR, respectively. There were no statistical differences between the sensitivity of the questionnaires, but specificity was significantly lower for the AIR compared to both the GAD-7 and the HADS-A (p < 0.001). Specificity of the GAD-7 was also significantly lower than for the HADS-A (p < 0.001). The screening accuracy of 83.0% of the HADS-A was significantly higher than both the GAD-7 (77.0%, p = 0.020) and the AIR (66.0%, p < 0.001).

Discussion

Main results

Three screening tools for depression had a 100% sensitivity to detect depression: The BASDEC, the BDI-II and the HADS-D. Both the BDI-II and the HADS-D were modified by the researchers by removal of an item. The BASDEC had the highest specificity of 93% followed by the GDS-15 and the HDSS with a specificity of 87% and 88%, respectively.

Concerning screening tools for anxiety, the GAI had the highest sensitivity of 86% and with a specificity of 78% the anxiety diagnosis was correctly made in 80% of the patients. The HADS-A was the most thoroughly tested screening tool as the validity was tested in three studies all using the MINI as the gold standard. Different optimal cut-off points ranging from ≥ 4 to ≥ 9 were suggested yielding a sensitivity ranging from 63% to 79% and a specificity ranging from 71% to 86%.

Depression screening tools

The HADS-D was developed by Zigmond et al. [Citation15] in 1983. Importantly, there are no questions related to somatic symptoms in the HADS-D. Phan et al. [Citation9] modified the questionnaire by removal of question 4 ("I feel as if I am slowed down") as apparently no patients scored 0 and there was no statistically significant difference in mean score of this question between depressed and non-depressed patients. The feeling of being slowed down could be interpreted as a universal symptom in patients with COPD and should be taken into consideration when evaluating depression screening tools for patients with COPD. A cut-off value ≥ 5 yields a sensitivity of 100% and a relatively high specificity. The ability to detect all true cases speaks in favour of using the HADS-D as a screening tool.

As well as in the HADS-D, Phan et al. [Citation9] found an item in the BDI-II with a mean score that did not differ between the patients with or without clinical depression and suggested to remove question 21 ("Loss of interest in sex"). Similar to the HADS-D, the BDI-II had a sensitivity of 100%.

The BASDEC showed great psychometric properties as well as a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 93%. The gold standard used in the only study validating the BASDEC by Yohannes et al. [Citation12] was the Geriatric Mental State Schedule, which is a semi-structured well-validated diagnostic interview [Citation16]. Unfortunately, the use of this diagnostic interview makes it difficult to compare the results of Yohannes et al. [Citation12] and Phan et al. [Citation9]

The HADS-D, the BDI-II and the BASDEC all have a high sensitivity and a high specificity, and the choice of screening tool must be based on relevant linguistic and cultural validation as well as longitudinal reliability and validation in patients with COPD. Further research is thus needed to recommend one specific screening tool.

Anxiety screening tools

The validity of the HADS-A was tested in three studies with the MINI as the gold standard; sensitivity ranged between 63% and 79%. The lowest sensitivity was found by Baker et al. [Citation14], who studied the largest patient population including 219 patients.

This relatively low sensitivity raises the question if the HADS-A is an appropriate anxiety screening tool. Interestingly, the optimal cut-off scores found in the three studies varied from ≥ 4 to ≥ 9. The cut-off score originally recommended by Zigmond et al. is ≥ 8 [Citation15]. The reasons for this discrepancy between the optimal cut-off scores are far from obvious as the study populations seem comparable. The low optimal cut-off score ≥ 4 on the HADS-A was found by Cheung et al. [Citation13], who also found an unusually low optimal cut-off score ≥ 3 on the GAI as the initial recommendation was ≥ 9. The GAI was found to have a high sensitivity of 86%, but the study lacks strength as it only included 55 patients.

The AIR questionnaire was designed for the purpose of detecting anxiety disorders in patients with COPD [Citation17]. Baker et al. [Citation14] found a low sensitivity of 66% and a specificity significantly lower than in both the HADS-A and the GAD-7. The GAD-7 was invented to detect generalised anxiety disorder and does not have a specific focus on for instance panic disorder.

Both the HADS-A, the GAI and the AIR do not contain items focussing on somatic symptoms. Review of the existing literature does not make it possible to recommend one specific screening tool for anxiety as the sensitivity of the tools is too low.

Strengths and weaknesses

The strengths of this study are the systematic literature review structure and that the PRISMA guidelines were followed to ensure transparency.

One of the weaknesses in this systematic review is that only seven studies met the inclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria ensuring that screening tools used in the included studies were compared with a diagnostic interview is also partly responsible for the relatively small number of included studies. This criterion was chosen as it would be impossible to compare the screening tools if they were validated against another screening tool as in Kunik et al. [Citation18]. As it appears from , seven potentially relevant studies were excluded for this reason. Unfortunately, the included studies used different types of diagnostic interviews making comparison of screening tools difficult. Ideally the gold standard in all of the included studies should have been use of the same diagnostic interview performed by a psychiatrist to compare the screening tools and the prevalence estimates.

Another disadvantage of the included studies was the relatively small number of included patients in the population samples; the largest sample of included patients was 219 in the study by Baker et al. [Citation14] but in four studies, the sample size was less than 60 patients.

Acute exacerbation of COPD was chosen to be an exclusion criterion as it is expected that such an event will provoke a panic attack thus making it difficult to differentiate between the acute exacerbation and a potential underlying anxiety disorder. This choice may have excluded relevant studies.

Also, in some studies, it was difficult to assess the patient’s condition. Aydin et al. [Citation10] included inpatients with COPD and the study did not clarify whether the patients were hospitalised due to an acute COPD exacerbation or if the reason for the hospitalisation was another medical illness. Furthermore, the study did not state whether the patients had been prescribed any kind of antibiotics or steroids during or prior to the hospitalisation. There is a potential risk of the study by Aydin et al. [Citation10] meeting the exclusion criteria, but since it was not stated in the study whether the patients had received antibiotics or steroids, we considered the study eligible for inclusion. This could potentially overestimate the prevalence of especially anxiety as it would be expected that many inpatients have symptoms of panic disorder corresponding to anxiety. None of the included patients in the study by Aydin et al. met the criteria for panic disorder and the authors highlight that their aim was to investigate the syndromal presence of generalised anxiety disorders and panic disorder and not anxiety-related symptoms.

The seven included studies were all at risk of selection bias as it is plausible that patients with COPD and comorbid depression or anxiety would be less likely to participate in the research programme. Julian et al. [Citation8] addressed this risk and suggested they reduced the risk of bias as their study was based on home visits and not outpatient visits. Phan et al. [Citation9] suggested that the risk of bias was opposite, as they suggested that patients with poorer mental health status were more likely to participate, thus inflating prevalence estimates.

In the study by Stage et al. [Citation11], the same health care person performed the HDSS as the diagnostic interview. This unblinded approach may be a source of bias. The study by Baker et al. [Citation14] did not blind the interviewer administering the MINI to the results of the screening tools, which potentially could also be a source of bias.

The study by Cheung et al. [Citation13] divided the study population into two groups; one group completed the rating scales at first and then underwent a diagnostic interview; the other group in the opposite order. In this study, two psychiatrists performed the diagnostic interview and evaluated the patient self-administered rating scales, but it was not clarified whether they were blinded to the previous results. The consequences of these potential sources of bias are difficult to evaluate as they can results in both overestimation as well as underestimation of depression and anxiety in COPD.

Clinical and scientific implications

This systematic review on the existing literature regarding the use of screening tools to detect depression and anxiety among patients with COPD has several scientific implications. Further research is needed to be able to recommend one specific screening tool.

Most importantly, consensus on the diagnostic interview as the gold standard is needed enabling comparison of different screening tools when benchmarked against the same standard. Ideally, the diagnostic interview should be performed by a trained psychiatrist or psychologist blinded to whether the screening tool fits the purpose or not.

Secondly, there is a need for studies examining larger patient cohorts. Many different screening tools for both depression and anxiety exist and many are designed not to focus on somatic symptoms. Results from Phan et al. [Citation9] suggest that some of the screening tools need to be modified to maximise sensitivity.

Furthermore, research is needed on optimal cut-off values of the different screening tools as they tend to vary between the included studies.

Screening tools with a high sensitivity to detect all patients with a possible depression or anxiety disorder are important in clinical practice. Choosing a screening tool with a high sensitivity allows the clinician to focus on the patients in need of treatment or referral for psychiatric consult. On the basis of this review, either the BASDEC, the BDI-II or the HADS-D is recommended for screening for depression among patients with stable COPD. However, it is not possible to recommend a screening tool for anxiety among this patient group as the sensitivity of the tools is low.

Conclusion

After systematically reviewing the existing literature on the use and validation of screening tools to detect depression in patients with COPD we conclude that the BASDEC and modified versions of the HADS-D and the BDI-II showed excellent sensitivity in detecting depression although the studies testing these screening tools lack strength due to small patient samples. Thus, these screening tools should be tested in a larger patient population.

Further knowledge is needed to recommend a specific anxiety screening tool as researchers disagree on the psychometric properties as well as the optimal cut-off score.

Registration

This systematic review was not registered in PROSPERO.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

Funding sources had no role in the design, conduct, and analysis of this study or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

References

- Maurer J, Rebbapragada V, Borson S, et al. Anxiety and depression in COPD: current understanding, unanswered questions, and research needs. Chest. 2008;134(4 Suppl):43S–56S. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.08-0342

- Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1789–1858.

- WHO: Burden of COPD. [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; [cited 2021 Apr 8]. Available from https://www.who.int/respiratory/copd/burden/en/.

- Lacasse Y, Rousseau L, Maltais F. Prevalence of depressive symptoms and depression in patients with severe oxygen-dependent chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2001;21(2):80–86.

- Harrison SL, Greening NJ, Williams JEA, et al. Have we underestimated the efficacy of pulmonary rehabilitation in improving mood?Respir Med. 2012;106(6):838–844. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2011.12.003

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1–e34. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006

- Julian LJ, Gregorich SE, Earnest G, et al. Screening for depression in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. COPD. 2009;6(6):452–458. DOI:https://doi.org/10.3109/15412550903341463

- Phan T, Carter O, Adams C, et al. Discriminant validity of the hospital anxiety and depression scale, beck depression inventory (II) and beck anxiety inventory to confirmed clinical diagnosis of depression and anxiety in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chron Respir Dis. 2016;13(3):220–228. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/1479972316634604

- Aydin IO, Ulaşahin A. Depression, anxiety comorbidity, and disability in tuberculosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: applicability of GHQ-12. Gen Hosp Psychiatr. 2001;23(2):77–83.

- Stage KB, Middelboe T, Pisinger C. Measurement of depression in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Nord J Psychiatry. 2003;57(4):297–301. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/08039480310002147

- Yohannes AM, Baldwin RC, Connolly MJ. Depression and anxiety in elderly outpatients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: prevalence, and validation of the BASDEC screening questionnaire. Int J Geriat Psychiatry. 2000;15(12):1090–1096. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-1166(200012)15:12<1090::AID-GPS249>3.0.CO;2-L

- Cheung G, Patrick C, Sullivan G, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of the geriatric anxiety inventory and the hospital anxiety and depression scale in the detection of anxiety disorders in older people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24(1):128–136. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610211001426

- Baker AM, Holbrook JT, Yohannes AM, et al. Test performance characteristics of the AIR, GAD-7, and HADS-Anxiety screening questionnaires for anxiety in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15(8):926–934. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201708-631OC

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–370. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x

- Copeland JR, Kelleher MJ, Kellet JM, et al. A semi-structured clinical interview for the assessment of diagnosis and mental state in the elderly: the geriatric mental state schedule. I. Development and reliability. Psychol Med. 1976;6(3):439–449. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291700015889

- Willgoss TG, Goldbart J, Fatoye F, et al. The development and validation of the anxiety inventory for respiratory disease. Chest. 2013;144(5):1587–1596. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.13-0168

- Kunik ME, Azzam PN, Souchek J, et al. A practical screening tool for anxiety and depression in patients with chronic breathing disorders. Psychosomatics. 2007;48(1):16–21. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psy.48.1.16