Abstract

Blood eosinophils have been proposed as a surrogate biomarker of airway eosinophilia that can be used for treatment decisions in patients with COPD, mainly for the identification of candidates for the initiation or withdrawal of therapy with inhaled corticosteroids, as well as for the identification of patients at future risk of exacerbations. In this manuscript we review the recent literature on blood eosinophils in the management of patients with COPD, in an attempt to answer the major questions that are relevant for the practicing clinician. A growing body of evidence suggests that eosinophilic COPD may constitute a separate phenotype of the disease with distinct clinical features and blood eosinophils may represent a potential candidate surrogate marker for specific COPD patients. Several points still need to be clarified, including the role of eosinophils for the identification of candidates for future COPD therapies, yet blood eosinophils plausibly represent the most dependable and promising biomarker for the precision management of COPD today.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) represents an important public health challenge. It is generally held that structural changes in this entity are the result of chronic airway inflammation. Airway inflammation is characterized by increased numbers of CD8 T lymphocytes, neutrophils, and macrophages; increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines; oxidative stress; and a state of protease/antiprotease imbalance [Citation1, Citation2]. Data on systemic biomarkers from large cohorts, are now available and provide exciting information on the association of biomarkers with clinically important outcomes, including exacerbations, hospitalizations, and mortality of COPD [Citation3]. However, the heterogeneity of the disease has hindered data interpretation and a detailed profile of disease-phenotype specific inflammation has yet to emerge. COPD inflammation research has increased rapidly, new treatments are being tested [Citation4], and interests are focused now not only on specific cell types, but more on the ‘‘whether, when and how’’ can use them.

Eosinophilic airway inflammation, a typical feature of asthma, has also been proposed as a treatable trait in COPD patients and according to recent epidemiological studies, eosinophilic COPD constitutes up to 32-40% of the overall COPD population [Citation5–7]. Nowadays, there is significant interest in the use of blood eosinophils as a possible biomarker in the management of COPD. More specifically, the 2020 GOLD strategy document suggests that blood eosinophil counts may assist in determining the likelihood of benefit of adding ICS to regular bronchodilator treatment in patients at risk of exacerbations [Citation8].

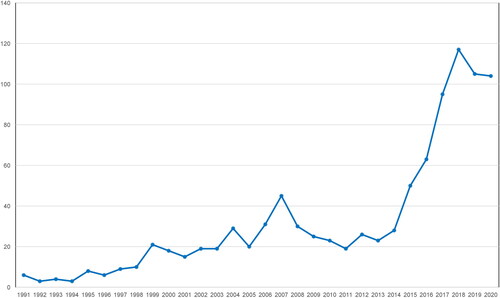

A burst of publications on blood eosinophils in COPD has been observed in recent years (). These studies have investigated eosinophilic airway inflammation in COPD as a promising target for inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) therapy, but discrepant results exist, and its role remains controversial. The present review aims to focus on ‘myths and reality’ concerning the role of blood eosinophils as a diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic biomarker in COPD.

The role of eosinophils in airways inflammation in COPD

Traditionally, the inflammatory response in COPD is more commonly associated with T helper 1 lymphocyte (Th1)-mediated immunity driven by neutrophils, often in response to bacterial colonization [Citation9]. However, due its heterogeneity, COPD may present as a number of different clinical phenotypes and recent evidence suggests that in around 10–40% of patients a degree of eosinophilic inflammation is present during stable state [Citation10]. It would not be an exaggeration to say that eosinophils remain mystifying cells. Νormally, they comprise less than 5% of the leukocytes in peripheral blood, but in response to type 2 helper T-cell (Th2)-mediated inflammation their production is greatly enhanced, and they become pivotal effector cells in inflammatory responses. In asthma, Th2-mediated eosinophilic airway inflammation predominates [Citation11, Citation12], whereas in COPD the typical pattern of airways inflammation is neutrophilic [Citation9]. Nevertheless, a wide spectrum of endotypes exists, from asthmatics without eosinophilic inflammation to COPD patients with eosinophilic inflammation [Citation10, Citation13].

Eosinophils are derived from bone marrow hematopoietic progenitors. Once inflammation occurs, they are activated by proinflammatory cytokines such as Interleukin-4 (IL-4), IL-5 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), eosinophils are recruited into the circulation and migrate to sites of inflammation. Extravasation into the airways is mediated by the interaction of cell surface integrins on eosinophils with adhesion molecules on the vascular endothelium, which enables transmigration across the bronchial vascular epithelium [Citation14]. Inside the airways, eosinophils release pro-inflammatory mediators, resulting in sustained inflammation and tissue damage [Citation15].

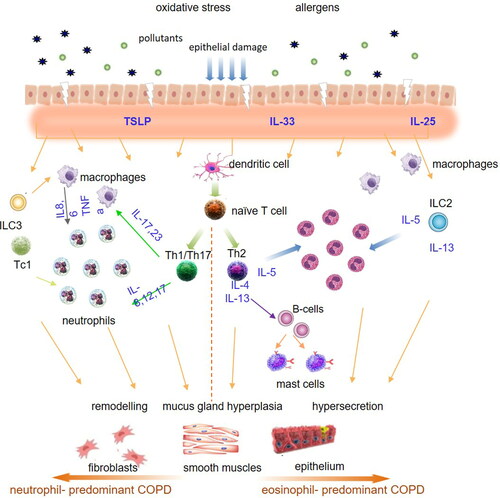

The precise mechanisms of eosinophilic inflammation in COPD are currently unknown. Current evidence suggests that in response to air pollutants and/or microbes, epithelium-derived cytokines [collectively called alarmins: IL-25, IL-33 and thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP)] are released, which in turn are involved in recruitment and activation of Th2 cells and type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2) [Citation16]. Th2 cells, together with ILC2 produce numerous Th2 cytokines, particularly interleukin (IL)-4, IL-5 and IL-13, which lead to the development of eosinophilia, mucus hypersecretion and airway hyper-reactivity [Citation17]. Among these cells, the Th2-associated cytokine IL-5 is the most specific cytokine for the eosinophil lineage and is responsible not only for the development of eosinophils from committed bone marrow progenitors, but also for their release into the blood and their survival following migration into the tissues [Citation18, Citation19]. shows the possible pathogenetic pathways in eosinophil-predominant and neutrophil-predominant COPD.

What is the role for blood eosinophils as a biomarker for COPD exacerbations?

Early detection and prevention of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease have always been the main goal of treatment, since they are likely to be associated with a reduction in morbidity, mortality, increased cost and perhaps accelerate the rate of progression of the disease. These events are heterogeneous with respect to etiology and inflammation and research has always aimed at finding biomarkers to phenotype this heterogeneity. In 2007, Shaw and coworkers published a randomized controlled trial (RCT) showed that a management strategy aiming to minimize eosinophilic airway inflammation and symptoms was associated with a significant reduction in COPD exacerbations requiring hospital admission [Citation20]. A few years later Bafadhel et al. [Citation21], in an observational, 1-year study of 182 exacerbations in 86 patients, identified four distinct biologic COPD exacerbation phenotypes: bacteria-predominant, viral-predominant, eosinophilic-predominant, and pauci-inflammatory. Τhe biomarkers that best identified these clinical phenotypes were sputum IL-1b, serum CXCL10 and percentage peripheral eosinophils. Based on these findings, blood eosinophils were proposed as a potential biomarker for the characterization of COPD exacerbations.

Βlood eosinophils have been evaluated as a biomarker for the guidance of oral corticosteroid therapy during COPD exacerbations. In a single-center double-blind randomized control trial (RCT), patients were randomized to receive prednisolone or biomarker-directed prednisolone therapy for exacerbations [Citation22]. Patients who had exacerbations associated with blood eosinophils >2% received prednisolone whereas those with eosinophil counts ≤2% did not; both groups received antibiotics. There was no difference in treatment failure or health status between subjects allocated to the biomarker-directed and standard therapy arms [Citation22]. More recently, an open-label multicenter Danish RCT (CORTICO-COP) in hospitalized COPD patients also reported noninferiority of the eosinophil-guided treatment in terms of days alive and out of hospital in 14 days follow-up, and a reduction of the duration of systemic corticosteroid exposure [Citation23]. Despite the fact that the study achieved its primary outcome, it did not have the sufficient statistical power to detect discrete worsening in important outcome measures such as readmission with acute exacerbations of COPD and death [Citation24]. In 2014, a meta-analysis of three clinical trials evaluated the effectiveness of treatment COPD exacerbations with oral corticosteroids in respect of blood eosinophilia [Citation25]. The primary outcome was the rate of treatment failures following treatment of an exacerbation, defined as retreatment, hospitalization, or death within 90 days of randomization, with patients grouped into prednisolone or non-prednisolone users and blood eosinophil count (<2% or ≥2%) at the time of exacerbation. The treatment failure rate was 66% in patients with a blood eosinophil count ≥2% who did not receive prednisolone and 11% in those who did; in contrast, in patients with a blood eosinophil count <2%, there was no difference in treatment failure rates with and without prednisolone (26% vs 20%). The authors proposed that blood eosinophils can be used for the guidance of treatment with corticosteroids in COPD exacerbations, however larger studies are definitely needed.

The role of blood eosinophils as a prognostic biomarker in COPD exacerbations has also been evaluated in observational studies. Steer and colleagues have developed a composite prognostic score, consisting of Dyspnea, Eosinopenia, Consolidation, Acidemia, and atrial Fibrillation, the DECAF-score: eosinopenia (<50 cells/μL) was identified as one of 5 key predictors of inpatient mortality in hospitalized AECOPD [Citation26]. In an observational study in Canada, authors analyzed data on hospitalizations for severe COPD exacerbation of 167 patients in an effort to investigate outcomes following these events according to blood eosinophil levels [Citation27]. The study demonstrated that blood eosinophil level ≥200 cells/μL and/or ≥2% of the total white blood cell count on admission, was associated with 3.59-fold increase in the risk of 12-month COPD-related readmission, 2.32-fold increase in the risk of 12-month all-cause readmission, and 2.74-higher chance of a shorter time to first COPD-related readmission. However, the length of stay was not statistically different between eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic patients. In contrast, in another study using similar criteria for blood eosinophilia, the mean length of stay was shorter in patients with eosinophilic than with non-eosinophilic exacerbations (5.0 days vs 6.5 days), whereas readmissions rates were similar in both groups [Citation28]. A more recent study using a retrospective derivation cohort (n = 242 patients) and a prospective validation (n = 99 patients) cohort evaluated AECOPD patients divided in 3 groups by blood eosinophils [low (<50/mL), normal (50-150/mL), or high (>150/mL) [Citation29]. In this study eosinopenia was associated with higher hospital stay and lower survival in the 12 months of follow-up compared to patients with eosinophil counts >150/mL [Citation29].

In a larger prospective study in tertiary hospitals in Greece, we evaluated the outcomes of 388 patients hospitalized for AECOPD based on baseline blood eosinophils at the time of admission [Citation30]. Confirming previous data, patients with blood eosinophil counts <50 μL had more dyspnea and worse oxygenation on admission, as well as higher C-reactive protein (CRP) levels indicative of infectious etiology of the exacerbation. Moreover, these patients had longer hospital stay and 30-day mortality, as well as higher mortality in the 1-year follow-up. Interestingly, in our analysis blood eosinophils at the onset of the AECOPD were not a predictor of future exacerbations [Citation30]. Collectively, our data combined with the previous studies suggest that blood eosinophils may represent a valid predictive biomarker for the identification of higher risk in patients hospitalized with AECOPD.

Are blood eosinophils a predictor of future risk for COPD exacerbations?

The role of eosinophils as a biomarker predicting the risk of future COPD exacerbations has been of considerable interest. In a large population-based study including 7225 participants with COPD in Denmark [Citation31], blood eosinophils above 340 cells/μL were associated with 3.21-fold increase in incidence rate for severe exacerbations and 1.69-fold for moderate exacerbations for the patients “clinical COPD”. Despite the fact that the current study is limited by having only prebronchodilator spirometry measurements, and thus the results might be confounded by individuals with undiagnosed asthma, this analysis was one of the first to suggest that absolute blood eosinophil count is a better predictor of exacerbations than percentage values. An analysis in the COPDGene and ECLIPSE cohorts has also shown that COPD patients with increased baseline blood eosinophil counts (≥300 cells/μL) were at a greater risk of disease exacerbations [Citation32]. In this analysis the authors were able to show that patients with blood eosinophil counts ≥300 cells/μL were more likely to have asthma-COPD overlap (ACO), and both eosinophilia and ACO were predictors of future exacerbation risk, however the two entities had some overlap but could not be used interchangeably [Citation32].

In an analysis in patients with at least 3 eosinophil counts over 2 years from the CHAIN and BODE cohorts, Casanova et al. examined the prevalence and stability of a blood eosinophil count of ≥300 cells/mL and its association with clinical outcomes [Citation33]. Blood eosinophil counts varied significantly over the 2 years of study period and there were no significant clinical differences between patients with persistently higher blood eosinophils and those without. Persistent eosinophilia was not associated with increased exacerbation risk but was associated with a lower risk of death during the follow-up period [Citation33]. In the SPIROMICS cohort of former and current smoking patients with a broad range of COPD severity in the US, higher levels of sputum eosinophils were a better predictor of exacerbation risk than blood eosinophils [Citation34]. Similarly, in a real-life French cohort study, there were no differences in terms of symptoms, lung function, exacerbation rate, and prognosis between COPD patients with higher versus lower blood eosinophil levels, for all tested thresholds of Eos (2%, 3%, and 4%) [Citation35]. Recently, Singh and coworkers evaluated blood eosinophil count, exacerbation history and prior use of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) as predictors of future COPD exacerbations, in a pooled analysis of data from 11 phase III and IV clinical trials, involving 22,125 patients [Citation36]. In this analysis, lower annual exacerbation rates were observed in patients with ≤150 cells/μL (0.62), with small increases in exacerbation rates with increasing eosinophil counts to 150-≤300 (0.65) and >300 cells/μL (0.67). In further analyses, the history of exacerbations and prior use of ICS were associated with higher exacerbation rates, leading the authors to suggest that in this context blood eosinophils cannot be used as predictor of future exacerbation risk [Citation36].

A large observational study in a UK population showed that 8.9% of COPD patients presented with marked blood eosinophilia (≥450 cells/mL) and these patients had an increased risk for future AECOPD (rate ratio 1.13) [Citation37]. The increased exacerbation risk was observed in patients who were ex-smokers and were receiving maintenance treatment with ICS [Citation37]. The aforementioned data suggest that blood eosinophils may not represent a universal biomarker for the prediction of future exacerbation risk in patients with stable COPD but may be more useful in certain subgroups of patients. At this point, it is worth mentioning when considering blood eosinophils as a predictor of future risk for COPD exacerbations, that many of the participants in ‘real world’ observational studies were already using ICS, especially those prone to exacerbations.

Can blood eosinophils be used as a predictor of ICS response in patients with stable COPD?

Recognition of eosinophilic inflammatory patterns in COPD patients, has led to the hypothesis that ICS could be effective in suppressing airway inflammation in COPD patients with blood eosinophilia. As a consequence, several post-hoc analyses on ICS efficacy in COPD patients were performed. In one of the first, Pascoe et al. showed that patients with baseline eosinophil count ≥2% had a significant reduction in their annual moderate-to-severe exacerbation rate when treated with ICS/long-acting β-agonists (LABA) versus LABA monotherapy; the effect was even more pronounced in patients with blood eosinophils ≥4% and ≥6% [Citation38]. In a post-hoc analysis of the FORWARD study, an increasingly greater reduction of the exacerbation rate was found in patients with higher blood eosinophil count classified into quartiles [Citation39]. Various blood eosinophil “cut points” for the efficacy of ICS/LABA vs. LABA alone for exacerbation prevention have been tested in post-hoc analyses of trials. In a detailed analysis of the studies of budesonide and formoterol in COPD, Bafadhel and colleagues showed a significant preventory effect of ICS at a level of approximately ≥100 cells/ml with the effect size increasing at higher counts; however, the most important observation of this analysis was that there is rather a continuous blood eosinophil concentration response [Citation40]. Interestingly, smoking history was the only additional predictor of response to an ICS/LABA vs. LABA in terms of exacerbation prevention in this analysis [Citation40].

In the comparison between ICS/LABA and LABA/long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMA), the initial data from the FLAME trial suggested that indacaterol glycopyrronium reduced exacerbation rates in patients with COPD and a history of exacerbations, both patients with higher (≥2%) and lower (<2%) blood eosinophil counts [Citation41]. An additional important learning from the FLAME eosinophil analyses, was that minimal change in blood eosinophils over 1 year of treatment with LABA/ICS in these COPD patients [Citation41]. Importantly, COPD patients were included in FLAME if they had a blood eosinophil count <600 cells/μL [Citation42]. In further analyses, however, this difference in efficacy was reduced with increased eosinophil counts, especially ≥300 cells/μL, irrespective of the number of exacerbations in the previous year [Citation43]. These early data suggested a benefit for ICS on top of a single bronchodilator in patients with increasing eosinophil counts. These and similar data support the GOLD 2021 document suggestion for consideration of LABA/ICS as starting therapy in patients with blood eosinophil counts ≥300 cells/µL [Citation44].

What is the role of blood eosinophils in the use of triple therapy (LAMA/LABA/ICS) vs. LAMA/LABA?

In recent years, large studies compared triple inhaled therapy (LAMA/LABA/ICS) vs. dual bronchodilation (LAMA/LABA) on exacerbation prevention in COPD patients with a history of exacerbations [Citation45–47]. The benefit on exacerbation prevention in all 3 studies was more prominent in patients with higher blood eosinophils. In the IMPACT study, triple therapy reduced the annual rate of moderate to severe exacerbations by 25% overall, with a 32% reduction in patients with ≥150 cells/μL compared to 12% in patients with <150 cells/μL [Citation46]. Similar benefits were observed also in the original reports of the TRIBUTE [Citation45] and the ETHOS [Citation47] studies, with cut-points of 200 and 150 cells/μL, respectively.

A further analysis of the IMPACT trial that evaluated blood eosinophil counts showed an improved benefit for triple therapy vs. LAMA/LABA with increasing blood eosinophil counts, concluding that assessment of blood eosinophil count has the potential to optimize ICS use in clinical practice in patients with COPD [Citation48]. An important additional finding of this analysis was that smoking habit may have an impact on the efficacy of ICS on top of LAMA/LABA, with a greater benefit overall in ex-smokers [Citation48]. A recent report of greater efficacy of LAMA/LABA versus LABA/ICS in current smokers, further supports the smaller beneficial effect of ICS in current smokers [Citation49]. Therefore, it would be of great interest to evaluate the role of triple therapy vs. LABA/LAMA in current vs. former smokers in clinical trials.

These data from RCTs are supported by real-world evidence analyses in primary care populations [Citation50, Citation51]. In a real-world population of COPD patients with history of exacerbations, Voorham and colleagues showed that the initiation of triple therapy was associated with a larger reduction in exacerbation or acute respiratory events risk compared with LAMA/LABA, and the benefit was more evident in patients with ≥350 cells/μL and in those with 3 or more exacerbations in the previous year [Citation51]. Similarly, Suissa and colleagues did not show an overall benefit for triple therapy vs. LAMA/LABA in the overall COPD population they evaluated, however they were able to show a 34% risk reduction in the risk for a COPD exacerbation with triple therapy vs. LAMA/LABA in patients with >6% blood eosinophils [Citation50].

The GOLD 2021 document recommends the use of triple therapy in exacerbating patients on LAMA/LABA with blood eosinophil counts ≥100 cells/μL, or as a step up from LABA/ICS when this combination has been selected in patients with ≥300 cells/μL [Citation44]. Similarly, the ATS guidelines for the pharmacologic management of stable COPD suggest that ICS can be added on top of long-acting bronchodilators (LABDs) in COPD patients with blood eosinophilia only when eosinophilia is combined with a history of exacerbations in the previous year [Citation52].

These recommendations are reasonable for exacerbating patients based on the existing clinical trials, however can triple therapy be provided in patients who are still symptomatic on LABA/LAMA? The ATS guidelines again provide a conditional recommendation for triple therapy in patients with dyspnea and a history of exacerbation [Citation52], however a more reasonable approach is provided by the NICE COPD guideline, suggesting a that patients can undergo a 3-month trial of triple therapy and revert to LAMA/LABA if there is no symptomatic improvement [Citation53]. This is supported by the data of the large triple therapy trials that provide also improvements in symptoms and quality of life vs. LAMA/LABA, however we need to remember that these trials were largely performed in exacerbating COPD patients [Citation46, Citation47].

What is the role of blood eosinophils in the decision for ICS withdrawal in patients with stable COPD?

In recent years there is an ongoing discussion around ICS withdrawal in stable COPD patients, that was reflected for the first time in 2019 in the GOLD document [Citation44]. The long-term use of high doses of ICS is associated with increased risk of adverse effects, including serious pneumonia [Citation54], bacterial colonization [Citation55], atypical mycobacterial infections [Citation56], new onset of diabetes [Citation57], and osteoporotic fractures [Citation58]. Recently, the European Respiratory Society issued a guideline on ICS withdrawal in COPD patients, providing conditional recommendation for ICS withdrawal in patients with <2 exacerbations and no hospitalizations in the previous year and blood eosinophil counts <300 cells/μL [Citation59]. The recommendation was based in secondary analyses of the WISDOM [Citation60] and SUNSET [Citation61] studies of ICS withdrawal from triple therapy. WISDOM evaluated the stepwise withdrawal of ICS from triple therapy in patients with a history of at least 1 exacerbation in the previous year [Citation62]. A post-hoc analysis of WISDOM showed that patients with higher blood eosinophil counts (≥4% or ≥300 cells/μL) were at higher risk after ICS withdrawal [Citation60]. SUNSET was the first study evaluating the direct de-escalation of ICS from long-term (at least 6 months) triple therapy to LABA/LAMA in a population of low-risk patients with COPD up to one exacerbation in the previous year [Citation61]. In a prespecified analysis, the study showed that annualized rates of moderate or severe COPD exacerbations were similar between the two treatment groups, with patients with higher blood eosinophil counts (≥300 cells/μL) presenting increased risk of exacerbations after ICS withdrawal; interestingly, the majority of exacerbation events occurred in the first month after ICS withdrawal [Citation61]. It is important to avoid ICS withdrawal in COPD patients who benefit from these drugs (e.g. those with asthmatic characteristics), as the abrupt withdrawal of ICS may lead to an acute increase in symptoms and early exacerbations [Citation63], and higher blood eosinophil counts may represent a good biomarker for the identification of patients at risk.

What is the appropriate cut-points for the identification of COPD patients who are likely to benefit from ICS for exacerbation prevention?

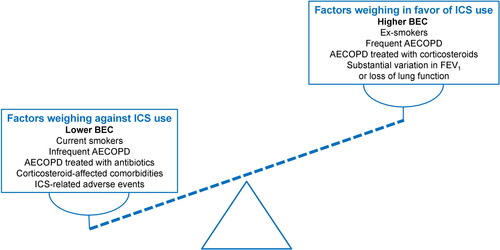

The efficacy and safety of inhaled corticosteroids in the treatment of patients with COPD is much debated, since it can result in clear clinical benefits in some patients but can be ineffective or even associated with pneumonia and other important side effects, in others. Patients with persistent counts <100-150 cells/μL are unlikely to benefit from ICS, based on currently available evidence, whereas those with >300-400 cells/μL are the most likely to benefit in terms of exacerbation prevention. In the in-between “gray zone” that has been discussed extensively in the literature [Citation64–66], several factors may guide our treatment decision to add an ICS on top of effective bronchodilation. Patients with at least 2 moderate or exacerbations are most likely to benefit, as they present the frequent exacerbator pattern that will benefit the most from ICS, as shown in major RCTs. In our opinion, frequent exacerbations cannot be used interchangeably with 1 hospitalization, despite the fact that hospitalized exacerbations may represent life-threatening events, as the decision for hospitalization may be based on the presence of comorbidities and may not necessarily be associated with eosinophilic inflammation. Rather than this, the treatment decision (use of antibiotics vs. use of systemic corticosteroids) may represent a more robust reason for the decision for ICS use, than the number of exacerbations alone [Citation67]. With accumulating evidence that ICS are less effective in current compared to ex-smokers [Citation49], and with the cut-point of blood eosinophils moving to higher levels in current smokers [Citation48], smoking status clearly plays a role in this decision. Last, but not least, the presence of corticosteroid-related comorbidities (especially diabetes and osteoporosis) and the history of serious adverse events potentially attributed to the long-term use of ICS (including but not limited to serious pneumonia, atypical mycobacterial infections, and bacterial colonization) may weigh in our clinical decision in favor or against ICS use, in parallel with blood eosinophil counts. In , we have attempted to incorporate all these factors that may support our decision for ICS use, based on blood eosinophil counts. In this Figure, blood eosinophils are considered as a continuous rather than a trichotomized variable (dashed line).

Figure 3. Factors affecting the decision for the use of ICS in stable COPD, focusing on the role of blood eosinophil counts. Dashed line represents schematically blood eosinophils as a continuous variable.

AECOPD: acute exacerbations of COPD; BEC: blood eosinophil counts; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 second.

Are we ready to use blood eosinophils in routine clinical practice?

Several controversies over the use of blood eosinophils as a routine biomarker exist. Blood eosinophil counts have been extensively investigated as a surrogate biomarker for eosinophilic airways inflammation and have been found to correlate relatively well with induced sputum eosinophil counts in some studies [Citation68]. Schleich and colleagues showed in a retrospective study of 155 patients that a blood eosinophil count >162 cells/μL identified patients with ≥3% sputum eosinophils with 71% sensitivity and 67% specificity, with a better diagnostic performance than the fraction of exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) [Citation69]. Overall, data concerning a positive correlation between sputum and peripheral eosinophils in COPD are ambiguous and it seems that the presence and strength of this correlation likely depends on disease severity [Citation70]. Therefore, it is important to understand that blood eosinophils represent a distinct biomarker that cannot be used interchangeably with sputum eosinophils.

Data from longitudinal studies suggest also that blood eosinophils present significant variability over time. In an analysis in two large databases in the UK and the US, Vogelmeier and colleagues observed significant variability in blood eosinophil counts over two consecutive years, that was more evident in patients with higher eosinophil counts; the lowest variability was observed in patients with <150 cells/μL [Citation71]. Similarly, a large population-based study in the UK showed that peripheral blood eosinophil counts present significant variability in patients with COPD compared; the stability of the eosinophilic phenotype (with a cutoff of 340 cells/μL) was 80% at 6 months, 63% at 2 years of follow-up, and declined to 18% at 8 years [Citation72]. Similar results of high within patient variability were also shown by Schummann et al. in a longitudinal analysis in a Swiss population, suggesting that a single measurement may not be a reliable predictor of ICS response [Citation73]. In a post-hoc analysis of the SUNSET study, the patients with the highest risk for exacerbations after ICS withdrawal were those who had consistently >300 cells/μL on two separate occasions [Citation61], suggesting a potential need for two consecutive measurements to reduce the exacerbation risk of the step down from triple therapy to LAMA/LABA. In a retrospective analysis of “real-life” data, Hamad and colleagues suggested that repeated measures of blood eosinophils, with a minimum of at least two counts, is necessary for the proper identification of the eosinophilic status of COPD patients [Citation74].

An additional important observation for clinical practice is the beneficial effect of roflumilast in decreasing exacerbations in patients with prior hospitalization for exacerbation and high blood eosinophil counts. This was confirmed in a predefined, pooled analyses of REACT (Roflumilast in the Prevention of COPD Exacerbations While Taking Appropriate Combination Treatment; NCT01329029) and RESPOND (Roflumilast Effect on Exacerbations in Patients on Dual [LABA/ICS] Therapy) multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies., by Martinez F. et coworkers [Citation75].

Does the future use of biologics in COPD include blood eosinophil measurements?

Many monoclonal antibodies have been developed for treatment of severe eosinophilic asthma and some of them have already been tested in exacerbating COPD patients with eosinophilia. Pavord et al evaluated the efficacy and safety of mepolizumab, a monoclonal antibody against interleukin-5, as add-on to triple inhaled therapy in patients with COPD who had an eosinophilic phenotype and a history of exacerbations, by conducting two phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, parallel group trials [Citation76]. In the METREX study patients were randomized to receive 100 mg mepolizumab or placebo and in the METREO study 100 mg or 300 mg mepolizumab or placebo. Although the safety profile of mepolizumab was similar to that of placebo in both trials, only the METREX study showed that mepolizumab at the dose of 100 mg was associated with a lower annual rate of moderate or severe exacerbations; however, in a pre-specified pooled analysis of the two studies, a higher beneficial effect for mepolizumab was observed in patients with ≥300 cells/μL [Citation76]. A phase 2a study evaluating the efficacy of benralizumab (a monoclonal antibody against the interleukin-5 receptor α) in patients with COPD and sputum eosinophilia, did not met its primary endpoint which was the reduction of the rate of acute exacerbations of COPD [Citation77]. Similarly, the two more recent GALATHEA and TERRANOVA studies evaluated the efficacy of benralizumab (a monoclonal antibody against the interleukin-5 receptor α) [Citation78]. In both studies, the addition of benralizumab did not reduce COPD exacerbations in patients with COPD with a history of frequent exacerbations and blood eosinophil counts ≥220 cells/μL. An important drawback of these 4 studies was the inclusion of mixed populations with some patients not presenting marked eosinophilia and a clear history of frequent exacerbations. A pooled post-hoc analysis of the GALATHEA and TERRANOVA benralizumab studies showed that patients with higher blood eosinophils, with ≥3 exacerbations in the previous year receiving triple therapy were those who benefited the most from anti-IL-5 treatment [Citation79]. These observations have led to the design of new trials of biologics in eosinophilic COPD that are currently ongoing [Citation80–82].

Conclusions and the way ahead

A growing body of evidence suggests that eosinophilic COPD is a separate phenotype of the disease with distinct clinical features and blood eosinophilia is a reasonable surrogate marker with the potential for widespread use. However, blood eosinophils are a modest predictor of sputum eosinophils [Citation69] and there is still debate about how blood eosinophil counts relate to airway eosinophil numbers [Citation34]. There is now some evidence that blood eosinophils can be used to drive treatment decisions in COPD exacerbations, however a proper large RCT is needed before recommending this. More specifically, it seems that blood eosinopenia can be used as a potential marker of adverse outcomes in COPD patients. Blood eosinophils are a modest predictor of future COPD exacerbations risk and may identify patients who will benefit the most from ICS, particularly in ex-smokers. The fact that the depletion of eosinophils by biologics has not clearly led to exacerbation prevention in the recent studies of anti-IL5 biologics, suggests that they may not represent a universal “treatable trait”, but rather a marker of ICS response in the prevention of COPD exacerbations. However, given the multifactorial effect of glucocorticoids on multiple cells and pathways related to airways inflammation in COPD, the association between blood eosinophil levels and ICS efficacy is not straightforward and, therefore, the use of blood eosinophil counts in COPD continues to be widely debated by the respiratory community. The absolute cut-points for the identification of appropriate patients for triple therapy, the response to ICS and the ability to withdraw ICS remain a subject of debate. We likely need more than one measurement to identify patients with “eosinophilic” phenotype (most likely two on stable condition), however - when identified - patients with persistent eosinophilia who are frequent exacerbators may be the appropriate candidates for biologic therapies targeting type-2 inflammation in the future. Although awaiting answers for these important questions, blood eosinophils represent the most dependable and promising biomarker for the precision management of COPD today.

Declaration of interest

Dr. Bartziokas has received honoraria for presentations and consultancy fees from AstraZeneca, Menarini, Chiesi, ELPEN, Novartis. Dr. Gogali has received honoraria for presentations and consultancy fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GSK, Novartis. Dr. Kostikas was an employee and shareholder of Novartis Pharma AG until 31/10/2018. He has received honoraria for presentations and consultancy fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, CSL Behring, ELPEN, GSK, Menarini, Novartis, Sanofi Genzyme, and WebMD. His department has received funding and grants from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Innovis, ELPEN, GSK, Menarini, Novartis and NuvoAir.

Funding

The author(s) reported there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

References

- Saetta M, Turato G, Facchini FM, et al. Inflammatory cells in the bronchial glands of smokers with chronic bronchitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156(5):1633–1639. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.156.5.9701081

- O’Shaughnessy TC, Ansari TW, Barnes NC, et al. Inflammation in bronchial biopsies of subjects with chronic bronchitis: inverse relationship of CD8+ T lymphocytes with FEV1. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155(3):852–857. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.155.3.9117016

- Kostikas K, Bakakos P, Papiris S, et al. Systemic biomarkers in the evaluation and management of COPD patients: are we getting closer to clinical application? Curr Drug Targets. 2013;14(2):177–191. DOI:https://doi.org/10.2174/1389450111314020005

- Martin RJ, Bel EH, Pavord ID, et al. Defining severe obstructive lung disease in the biologic era: an endotype-based approach. Eur Respir J. 2019;54(5):1900108. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00108-2019

- Leigh R, Pizzichini MM, Morris MM, et al. Stable COPD: predicting benefit from high-dose inhaled corticosteroid treatment. Eur Respir J. 2006;27(5):964–971. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.06.00072105

- Proboszcz M, Mycroft K, Paplinska-Goryca M, et al. Relationship between blood and induced sputum eosinophils, bronchial hyperresponsiveness and reversibility of airway obstruction in mild-to-Moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. COPD. 2019;16(5–6):354–361. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/15412555.2019.1675150

- Kim VL, Coombs NA, Staples KJ, et al. Impact and associations of eosinophilic inflammation in COPD: analysis of the AERIS cohort. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(4):1700853. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00853-2017

- Website [Internet]. [cited 2020 May 1]. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 2020 report. https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/GOLD-2020-REPORT-ver1.1wms.pdf.

- Barnes PJ. Inflammatory mechanisms in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(1):16–27. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2016.05.011

- George L, Brightling CE. Eosinophilic airway inflammation: role in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2016;7(1):34–51. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/2040622315609251

- Woodruff PG, Modrek B, Choy DF, et al. T-helper type 2-driven inflammation defines major subphenotypes of asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(5):388–395. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200903-0392OC

- Robinson D, Humbert M, Buhl R, et al. Revisiting type 2-high and type 2-low airway inflammation in asthma: current knowledge and therapeutic implications. Clin Exp Allergy. 2017;47(2):161–175. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1111/cea.12880

- Fahy JV. Type 2 inflammation in asthma-present in most, absent in many. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15(1):57–65. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1038/nri3786

- Kostikas K, Brindicci C, Patalano F. Blood eosinophils as biomarkers to drive treatment choices in asthma and COPD. Curr Drug Targets. 2018;19(16):1882–1896. DOI:https://doi.org/10.2174/1389450119666180212120012

- Tashkin DP, Wechsler ME. Role of eosinophils in airway inflammation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018;13:335–349. DOI:https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S152291

- Ying S, O’Connor B, Ratoff J, et al. Expression and cellular provenance of thymic stromal lymphopoietin and chemokines in patients with severe asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Immunol. 2008;181(4):2790–2798. DOI:https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.181.4.2790

- Brusselle GG, Maes T, Bracke KR. Eosinophils in the spotlight: Eosinophilic airway inflammation in nonallergic asthma. Nat Med. 2013;19(8):977–979. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.3300

- Rosenberg HF, Dyer KD, Foster PS. Eosinophils: changing perspectives in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13(1):9–22. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1038/nri3341

- Lopez AF, Sanderson CJ, Gamble JR, et al. Recombinant human interleukin 5 is a selective activator of human eosinophil function. J Exp Med. 1988;167(1):219–224. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.167.1.219

- Siva R, Green RH, Brightling CE, et al. Eosinophilic airway inflammation and exacerbations of COPD: a randomised controlled trial. Eur Respir J. 2007;29(5):906–913. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00146306

- Bafadhel M, McKenna S, Terry S, et al. Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: identification of biologic clusters and their biomarkers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184(6):662–671. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201104-0597OC

- Bafadhel M, McKenna S, Terry S, et al. Blood eosinophils to direct corticosteroid treatment of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(1):48–55. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201108-1553OC

- Sivapalan P, Lapperre TS, Janner J, et al. Eosinophil-guided corticosteroid therapy in patients admitted to hospital with COPD exacerbation (CORTICO-COP): a multicentre, randomised, controlled, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7(8):699–709. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30176-6

- Lapperre TS, Janner J, Laub RR, et al. Eosinophil-Guided Corticosteroid-Sparing Therapy in Hospitalized Patients with Exacerbated COPD(CORTICOsteroid Reduction in COPD (CORTICO-COP)): A Randomized Prospective Multicenter Investigator-Initiated Trial. B14. LATE BREAKING CLINICAL TRIALS. p. A7352–A7352.

- Bafadhel M, Davies L, Calverley PM, et al. Blood eosinophil guided prednisolone therapy for exacerbations of COPD: a further analysis. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(3):789–791. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00062614

- Steer J, Gibson J, Bourke SC. The DECAF score: predicting hospital mortality in exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2012;67(11):970–976. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202103

- Couillard S, Larivee P, Courteau J, et al. Eosinophils in COPD exacerbations are associated with increased readmissions. Chest. 2017;151(2):366–373. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2016.10.003

- Bafadhel M, Greening NJ, Harvey-Dunstan TC, et al. Blood eosinophils and outcomes in severe hospitalized exacerbations of COPD. Chest. 2016;150(2):320–328. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2016.01.026

- MacDonald MI, Osadnik CR, Bulfin L, et al. Low and high blood eosinophil counts as biomarkers in hospitalized acute exacerbations of COPD. Chest. 2019;156(1):92–100. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2019.02.406

- Kostikas K, Papathanasiou E, Papaioannou AI, et al. Blood eosinophils as predictor of outcomes in patients hospitalized for COPD exacerbations: a prospective observational study. Biomarkers. 2021;26(4):354–362. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/1354750X.2021.1903998

- Vedel-Krogh S, Nielsen SF, Lange P, et al. Blood eosinophils and exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The Copenhagen general population study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(9):965–974. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201509-1869OC

- Yun JH, COPDGene and ECLIPSE Investigators, Lamb A, Chase R, et al. Blood eosinophil count thresholds and exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141(6):2037–2047.e10.

- Casanova C, Celli BR, de-Torres JP, et al. Prevalence of persistent blood eosinophilia: relation to outcomes in patients with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(5):1701162. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01162-2017

- Hastie AT, Martinez FJ, Curtis JL, et al. Association of sputum and blood eosinophil concentrations with clinical measures of COPD severity: an analysis of the SPIROMICS cohort. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5(12):956–967. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30432-0

- Zysman M, Deslee G, Caillaud D, et al. Relationship between blood eosinophils, clinical characteristics, and mortality in patients with COPD. COPD. 2017;12:1819–1824. DOI:https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S129787

- Singh D, Wedzicha JA, Siddiqui S, et al. Blood eosinophils as a biomarker of future COPD exacerbation risk: pooled data from 11 clinical trials. Respir Res. 2020;21(1):240. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-020-01482-1

- Kerkhof M, Sonnappa S, Postma DS, et al. Blood eosinophil count and exacerbation risk in patients with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(1):1700761. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00761-2017

- Pascoe S, Locantore N, Dransfield MT, et al. Blood eosinophil counts, exacerbations, and response to the addition of inhaled fluticasone furoate to vilanterol in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a secondary analysis of data from two parallel randomised controlled trials. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3(6):435–442. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00106-X

- Siddiqui SH, Guasconi A, Vestbo J, et al. Blood eosinophils: a biomarker of response to extrafine beclomethasone/formoterol in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192(4):523–525. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201502-0235LE

- Bafadhel M, Peterson S, De Blas MA, et al. Predictors of exacerbation risk and response to budesonide in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a post-hoc analysis of three randomised trials. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6(2):117–126. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30006-7

- Roche N, Chapman KR, Vogelmeier CF, et al. Blood eosinophils and response to maintenance chronic obstructive pulmonary disease treatment. Data from the FLAME trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(9):1189–1197. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201701-0193OC

- Wedzicha JA, Banerji D, Chapman KR, et al. Indacaterol-glycopyrronium versus salmeterol-fluticasone for COPD. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(23):2222–2234. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1516385

- Papi A, Kostikas K, Wedzicha JA, et al. Dual bronchodilation response by exacerbation history and eosinophilia in the FLAME study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197(9):1223–1226. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201709-1822LE

- GOLD Reports. 2021. [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2021 May 5]. Available from: https://goldcopd.org/2021-gold-reports/.

- Papi A, Vestbo J, Fabbri L, et al. Extrafine inhaled triple therapy versus dual bronchodilator therapy in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (TRIBUTE): a double-blind, parallel group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10125):1076–1084. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30206-X

- Lipson DA, Barnhart F, Brealey N, et al. Once-Daily Single-Inhaler triple versus dual therapy in patients with COPD. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(18):1671–1680. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1713901

- Rabe KF, Martinez FJ, Ferguson GT, et al. Triple inhaled therapy at two glucocorticoid doses in moderate-to-Very-Severe COPD. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(1):35–48. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1916046

- Pascoe S, Barnes N, Brusselle G, et al. Blood eosinophils and treatment response with triple and dual combination therapy in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: analysis of the IMPACT trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7(9):745–756. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30190-0

- Halpin DMG, Vogelmeier CF, Mezzi K, et al. Efficacy of indacaterol/glycopyrronium versus salmeterol/fluticasone in current and ex-smokers: a pooled analysis of IGNITE trials. ERJ Open Res. 2021;7(1):00816–2020. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1183/23120541.00816-2020

- Suissa S, Dell’Aniello S, Ernst P. Comparative effects of LAMA-LABA-ICS vs LAMA-LABA for COPD: Cohort study in Real-World clinical practice. Chest. 2020;157(4):846–855. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2019.11.007

- Voorham J, Corradi M, Papi A, et al. Comparative effectiveness of triple therapy versus dual bronchodilation in COPD. ERJ Open Res. 2019;5(3):00106–2019. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1183/23120541.00106-2019

- Nici L, Mammen MJ, Charbek E, et al. Pharmacologic management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. An official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(9):e56–e69. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202003-0625ST

- Overview | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in over 16s: diagnosis and management | Guidance | NICE. NICE; 2021. [cited 2021 May 8]; Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng115.

- Suissa S, Patenaude V, Lapi F, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids in COPD and the risk of serious pneumonia. Thorax. 2013;68(11):1029–1036. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202872

- Contoli M, Pauletti A, Rossi MR, et al. Long-term effects of inhaled corticosteroids on sputum bacterial and viral loads in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(4):1700451. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00451-2017

- Brode SK, Campitelli MA, Kwong JC, et al. The risk of mycobacterial infections associated with inhaled corticosteroid use. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(3):1700037. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00037-2017

- Price DB, Voorham J, Brusselle G, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids in COPD and onset of type 2 diabetes and osteoporosis: matched cohort study. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2019;29(1):38.

- Gonzalez AV, Coulombe J, Ernst P, et al. Long-term use of inhaled corticosteroids in COPD and the risk of fracture. Chest. 2018;153(2):321–328. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2017.07.002

- Chalmers JD, Laska IF, Franssen FME, et al. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids in COPD: a european respiratory society guideline. Eur Respir J. 2020;55(6):2000351. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00351-2020

- Watz H, Tetzlaff K, Wouters EF, et al. Blood eosinophil count and exacerbations in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease after withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids: a post-hoc analysis of the WISDOM trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4(5):390–398. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(16)00100-4

- Chapman KR, Hurst JR, Frent SM, et al. Long-term triple therapy de-escalation to indacaterol/glycopyrronium in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (SUNSET): a randomized, Double-Blind, Triple-Dummy clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198(3):329–339. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201803-0405OC

- Magnussen H, Disse B, Rodriguez-Roisin R, et al. Withdrawal of inhaled glucocorticoids and exacerbations of COPD. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(14):1285–1294. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1407154

- Wedzicha JA, Banerji D, Kostikas K. Single-Inhaler triple versus dual therapy in patients with COPD. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(6):591. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc1807380

- Brusselle GG, Bracke K, Lahousse L. Targeted therapy with inhaled corticosteroids in COPD according to blood eosinophil counts. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3(6):416–417. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00145-9

- Agusti A, Fabbri LM, Singh D, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids in COPD: friend or foe? Eur Respir J. 2018;52(6):1801219. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01219-2018

- Stolz D, Miravitlles M. The right treatment for the right patient with COPD: lessons from the IMPACT trial. Eur Respir J. 2020;55(5):2000881. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00881-2020

- Vogelmeier CF, Chapman KR, Miravitlles M, et al. Exacerbation heterogeneity in COPD: subgroup analyses from the FLAME study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018;13:1125–1134. DOI:https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S160011

- van Bragt J, Vijverberg SJH, Weersink EJM, et al. Blood biomarkers in chronic airways diseases and their role in diagnosis and management. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2018;12(5):361–374. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/17476348.2018.1457440

- Schleich F, Corhay JL, Louis R. Blood eosinophil count to predict bronchial eosinophilic inflammation in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2016;47(5):1562–1564. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01659-2015

- Turato G, Semenzato U, Bazzan E, et al. Blood eosinophilia neither reflects tissue eosinophils nor worsens clinical outcomes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197(9):1216–1219. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201708-1684LE

- Vogelmeier CF, Kostikas K, Fang J, et al. Evaluation of exacerbations and blood eosinophils in UK and US COPD populations. Respir Res. 2019;720(1):178. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-019-1130-y

- Oshagbemi OA, Burden AM, Braeken DCW, et al. Stability of blood eosinophils in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and in control subjects, and the impact of sex, age, smoking, and baseline counts. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(10):1402–1404. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201701-0009LE

- Schumann DM, Tamm M, Kostikas K, et al. Stability of the blood eosinophilic phenotype in stable and exacerbated COPD. Chest. 2019;156(3):456–465. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2019.04.012

- Hamad GA, Cheung W, Crooks MG, et al. Eosinophils in COPD: how many swallows make a summer? Eur Respir J. 2018;51(1):1702177. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.02177-2017

- Martinez FJ, Rabe KF, Calverley PMA, et al. Determinants of response to roflumilast in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Pooled analysis of two randomized trials. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198(10):1268–1278. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201712-2493OC

- Pavord ID, Chanez P, Criner GJ, et al. Mepolizumab for eosinophilic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(17):1613–1629. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1708208

- Brightling CE, Bleecker ER, Panettieri RA, Jr, et al. Benralizumab for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and sputum eosinophilia: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2a study. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(11):891–901. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70187-0

- Criner GJ, Celli BR, Brightling CE, et al. Benralizumab for the prevention of COPD exacerbations. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(11):1023–1034. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1905248

- Criner GJ, Celli BR, Singh D, et al. Predicting response to benralizumab in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: analyses of GALATHEA and TERRANOVA studies. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(2):158–170. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30338-8

- Efficacy and Safety of Benralizumab in Moderate to Very Severe Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) With a History of Frequent Exacerbations - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.Gov [Internet]. [cited 2021 May 8]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04053634.

- Case medical research. Mepolizumab as add-on treatment in participants with COPD characterized by frequent exacerbations and eosinophil level (MATINEE). Case Med Res [Internet] Case J. 2019. [cited 2021 May 8]; Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04133909.

- Pivotal Study to Assess the Efficacy, Safety and Tolerability of Dupilumab in Patients With Moderate to Severe COPD With Type 2 Inflammation - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.Gov [Internet]. [cited 2021 May 8]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04456673.