Abstract

Long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT) reduces hypoxaemia and mitigate systemic alterations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), however, it is related to inactivity and social isolation. Social participation and its related factors remain underexplored in individuals on LTOT. This study investigated social participation in individuals with COPD on LTOT and its association with dyspnoea, exercise capacity, muscle strength, symptoms of anxiety and depression, and quality of life. The Assessment of Life Habits (LIFE-H) assessed social participation. The modified Medical Research Council dyspnoea scale, the 6-Minute Step test (6MST) and handgrip dynamometry were used for assessments. In addition, participants responded to the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and the Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire (CRQ). Correlation coefficients and multivariate linear regression analyses were applied. Fifty-seven participants with moderate to very severe COPD on LTOT were included (71 ± 8 years, FEV1: 40 ± 17%predicted). Social participation was associated with dyspnoea (rs=–0.46, p < 0.01), exercise capacity (r = 0.32, p = 0.03) and muscle strength (r = 0.25, p = 0.05). Better participation was also associated with fewer depression symptoms (rs=–0.40, p < 0.01) and a better quality of life (r = 0.32, p = 0.01). Dyspnoea was an independent predictor of social participation (p < 0.01) on regression models. Restricted social participation is associated with increased dyspnoea, reduced muscle strength and exercise capacity. Better participation is associated with fewer depression symptoms and better quality of life in individuals with COPD on LTOT.

Introduction

COPD is a leading cause of chronic morbidity [Citation1], and is projected to be the fourth leading cause of death in 2030 [Citation2]. Although COPD mainly affects the respiratory system, it is a systemic disease that presents with reduced exercise capacity and peripheral muscle dysfunction, particularly in those with severe stages [Citation3]. Approximately 7% of individuals with moderate to severe COPD develop chronic hypoxaemia within five years of diagnosis requiring the use of supplemental home long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT) [Citation4]. Also, chronic hypoxaemia may aggravate the disease progression, reduce the physical activity performed in daily life, restrict mobility and social interaction [Citation5].

Individuals with COPD recognise the importance of engagement in activities of daily living, including walking and household maintenance, although these activities are restricted around the home environment. This restriction may lead to feelings of social isolation [Citation6]. Social participation can be defined as ‘a person’s involvement in activities that provide interaction with others in society or the community’ [Citation7], it is related to healthy ageing and assists older adults on physical and psychological well-being [Citation8]. Importantly, reduced social engagement is associated with an increased risk of respiratory disease hospital admissions [Citation9].

Individuals with COPD on LTOT have a greater dependence on performing the activity of daily living compared to their non-oxygen dependent peers [Citation10]; particularly due to embarrassment, the stationary oxygen supply equipment, or inability to carry because of the equipment weight [Citation11]. Although the reduced level of activities of daily living has been documented in COPD [Citation12], information about social participation in this population is scarce [Citation13], mainly in those on LTOT. Also, factors that may influence social participation in individuals with COPD on LTOT remain underexplored including dyspnoea, exercise capacity and muscle strength, modifiable outcomes commonly targeted in medical care and rehabilitation programs [Citation13]. Positive health outcomes associated with better social participation have been identified in older adults, including fewer depression symptoms, a better quality of life and reduced mortality risk [Citation14]. These associations have not been explored in individuals with COPD on LTOT.

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the associations between dyspnoea, exercise capacity and muscle strength with social participation. As a secondary objective, the association between social participation and anxiety, depression and quality of life were explored. It was hypothesised that individuals with COPD on LTOT with less dyspnoea, better exercise capacity and muscle strength have greater social participation, which could influence symptoms of anxiety and depression and quality of life.

Methods

Study design and participants

This is a cross-sectional study reported according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology recommendations [Citation15]. Data were collected between January 2019 and March 2020. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Juiz de Fora Hospital, Brazil (2.772.793/2018). All participants signed informed consent.

A convenience sample of subjects registered on two public health care long-term home oxygen therapy databases were enrolled in this study. Eligible participants were contacted and home visits were scheduled for assessments of included participants. All assessments were performed by previously trained cardiorespiratory physiotherapists. Inclusion criteria were diagnosis of COPD [Citation1]; clinical stability in the 30 days before the assessments; on LTOT for at least 3 months before enrolment in the study, and living in the community at a reachable distance for study assessments. Exclusion criteria were the inability to perform or understand the study assessments due to physical or psychological impairment and a primary diagnosis of a respiratory disease other than COPD. Pulmonary function was performed using a calibrated spirometer (Datospir Micro C®, Sibelmed, Spain and Spirobank II Advanced, Italy) following the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society technical statement [Citation16]. Reference equations were used for predicted values [Citation17]. The severity of airway obstruction was classified according to the GOLD criteria [Citation1].

Measures

Social participation

The short version of the Assessment of Life Habits (LIFE-H, version 3.0) was used. The LIFE-H is a reliable instrument to assess social participation in the elderly [Citation18]. The questionnaire includes 77 questions with 12 categories of life habits. The LIFE-H is divided into two main domains: daily activities (nutrition, fitness, personal care, communication, housing, and mobility) and social roles (responsibilities, interpersonal relationships, community life, education, employment, and recreation). The scoring is based on the level of accomplishment and type of the required assistance during activities related to social participation, including technical assistance, physical arrangements, and human help. Each question is rated from zero, which represents total restriction in participation and the life habits not accomplished; to nine, which represents the maximal level of participation and life habits performed without difficulty and help. For each category, a score of 0 to 10 is calculated. The non-applicable items are removed from the calculation. The total score is also provided on a 0 to 10 scale as the mean of the categories assessed. Higher scores indicate higher levels of social participation [Citation19]. The cutoff score that identifies difficulties accomplishing activities assessed in LIFE-H categories was set at a level where the participants were experiencing difficulties or needing assistance to accomplish housing-related activities (weighted score ≤7) [Citation20].

Dyspnoea, exercise capacity and muscle strength

Dyspnoea was assessed using the modified Medical Research Council dyspnoea scale (mMRC) [Citation21]. The 6-Minute Step test (6MST) was used to assess exercise capacity. The general principles of the test were based on American Thoracic Society recommendations [Citation22]. A single 20-cm-high step is used as an ergometer. The participant is asked to go up and down the step as fast as possible for 6 min and can slow down or stop if necessary. The number of climbed steps is recorded. All participants underwent the 6MST using the oxygen flow as prescribed, heart rate and pulse oximetry were monitored. The 6MST is a valid and reliable field exercise test in individuals with COPD [Citation22]. The reference equations were used to estimate the predicted number of climbed steps [Citation23].

Peripheral muscle strength was measured using an adjustable handgrip dynamometer (Saehan Corporation, 973, Yangdeok-Dong, Masan 630-728, Korea). The participants are instructed to sit down with elbows positioned at ninety degrees on the chair armrests holding the dynamometer in a forearm neutral position. Handgrip strength is recorded on the dominant hand based on the two-to-three seconds maximal muscle contraction. A 30-s rest is allowed between assessments and the highest value in kilogram-force between three attempts with less than 10% variation recorded. The handgrip dynamometer has excellent intra- and inter-rater reliability [Citation24]. The reference equations were used to estimate the predicted handgrip strength [Citation25].

Anxiety, depression and quality of life

Anxiety and depression symptoms were assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). The HADS has fourteen items, seven relate to symptoms of anxiety and seven to symptoms of depression. Each item is scored from 0 to 3. Higher scores indicate more frequent symptoms. The scale has good sensitivity and specificity to identify anxiety and depression symptoms in individuals with COPD [Citation26].

The Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire (CRQ) was used to assess the quality of life. The CRQ consists of twenty questions divided into four domains: dyspnoea, fatigue, emotional function, and self-control. The higher the score, the better the individual’s quality of life. The CRQ is a reproducible and valid instrument to assess health-related quality of life in individuals with COPD [Citation27].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics are reported as absolute values, percentages, median and percentiles (25–75th), and mean ± standard deviation. Shapiro–Wilk test was used to check the normality of the data. Spearman (rs) and Pearson (r) correlation coefficients were used to determine the associations. Correlation coefficients were interpreted according to Schober et al. [Citation28]. Stepwise multiple linear regression analyses were used to evaluate the influence of dyspnoea, exercise capacity and muscle strength on social participation. Multicollinearity was checked by inspecting the tolerance values/variance inflation factors (VIF) and the correlation coefficients among independent variables. The absence of multicollinearity was considered when tolerance values were greater than 0.1 (which is a VIF less than 10) and correlation coefficients below 0.7 [Citation29]. Missing data were addressed in a complete case analysis. The IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows software v. 22.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all data analyses. All p values were two-tailed with values ≤0.05 considered as statistical significance.

Results

Participants characteristics

A total of a hundred and ninety-two individuals were registered on the two public health care long-term home oxygen therapy databases. A hundred and five had a primary clinical diagnosis of COPD and met the inclusion criteria, of these, thirty-eight were not assessed due to COVID-19 pandemic restrictions and ten refused to participate. Fifty-seven participants were included in the analysis. summarises the participant’s characteristics. The study sample was predominantly female, and most had moderate to severe COPD, on GOLD Stage 3. Three participants were in pulmonary rehabilitation at the time of assessments, and the remainder had not participated in rehabilitation programmes previously. The median of LTOT lifetime use was 1.3 years for 14 h/day.

Table 1. Characteristics of participants.

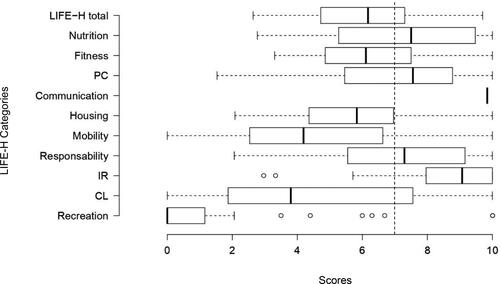

shows data on social participation and the secondary outcomes studied. Participants showed difficulties accomplishing general participation activities (score ≤ 7) in the LIFE-H total score, and the Fitness, Housing, Mobility, Community life and Recreation categories. Education and Work items were non-applicable due to retirement or no participation in educational activities or vocational training (). Participants also performed 48.1% of the predicted number of steps on the 6MST and presented with 71.2% of the predicted hang-grip muscle strength.

Figure 1. Participants’ score on the Assessment of Life Habits (LIFE-H) domains: daily activities (nutrition, fitness, PC, communication, housing, and mobility) and social roles (responsibilities, IR, CL and recreation). Education and Employment were nonapplicable. Centre lines show the medians; box limits indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles; whiskers extend 1.5 times the interquartile range from the 25th and 75th percentiles, outliers are represented by dots. Abbreviations: PC: personal care; IR: interpersonal relationship; CL: community life. Weighted score ≤ 7 (vertical dashed line): experiencing difficulties or needing assistance to accomplish activities.

Table 2. Social participation, dyspnoea, exercise capacity, muscle strength, anxiety, depression, and quality of life.

Relationships between social participation and dyspnoea, exercise capacity, muscle strength, symptoms of anxiety and depression, and quality of life in individuals with COPD on LTOT are shown in . Less dyspnoea, better exercise capacity and predicted handgrip muscle strength presented moderate to weak associations with better social participation. Better social participation was associated with less depression, whereas there was no association with anxiety symptoms. Better social participation also had weak to moderate associations with better quality of life, particularly in the CRQ Fatigue and Mastery domains. In the multiple linear regression, the three factors explained 20% of participants’ social participation, only dyspnoea was kept as a significant independent predictor of social participation in the models analysed (). Multicollinearity was not identified between variables.

Table 3. Associations between social participation and dyspnoea, exercise capacity, muscle strength, anxiety, depression, and quality of life (n = 57).

Table 4. Multiple linear regression models of factors associated with social participation as measured by LIFE-H.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate social participation in individuals with COPD on LTOT. The main findings were: (1) social participation is reduced in these individuals, mainly on the Fitness, Housing, Mobility, Community life and Recreation categories; (2) increased dyspnoea, reduced exercise capacity and muscle strength are factors associated with poor social participation; (3) reduced social participation is also related with depression symptoms and worse quality of life in individuals with COPD on LTOT.

The reduced social participation found in individuals with COPD on LTOT agrees with a previous survey in more than two hundred individuals with COPD, which demonstrated reduced participation in daily and social activities. Of note, participants demonstrated a willingness to increase participation, it was limited mainly by dyspnoea [Citation13]. The higher number of individuals with severe and very-severe COPD on LTOT and, consequently more severe dyspnoea, may have contributed to the restricted social participation observed in our sample. Importantly, social disengagement is associated with an increased risk of hospital admission [Citation9]. Social isolation is a potential mechanism to increase the risk of being physically inactive, increase dyspnoea due to long-term deconditioning, increase smoking, and restricts social support to call for medical attention early in the development of a respiratory exacerbation [Citation9].

Although LTOT promotes symptom relief, it may contribute to restricted social interaction due to the shame and mobility difficulties related to the use of oxygen equipment in public, restraining its continued use in the home environment [Citation30]. Other factors may also negatively influence social participation in individuals on LTOT, including excessive care of family members and caregivers in everyday situations due to disease severity, limited physical functioning independence, and mobility outside the home [Citation31]. Of note, the levels of social participation observed in individuals with COPD on LTOT in this study were lower than values reported in individuals with neurological disorders due to stroke [Citation32].

Social participation was associated with exercise capacity and muscle strength in individuals with COPD on LTOT. The association of exercise capacity and muscle strength with physical activity are documented in individuals with COPD users and non-users of LTOT [Citation5, Citation33]. The beneficial effects on muscle strength and exercise capacity provided by pulmonary rehabilitation, which contributes to increased physical activity [Citation3], may improve the social participation in individuals with COPD on LTOT. Only 5% of the participants were enrolled in pulmonary rehabilitation at the time of study assessments, which may have also influenced the limited levels of social participation observed.

Improvement in physical activity may not be the only factor that translates to better social interaction. The importance of social support from various sources including healthcare professionals, family, friends, and neighbours are essential for participants in pulmonary rehabilitation, relating to better treatment adherence [Citation34]. Participation in group interventions provides opportunities for sharing knowledge, encourages mutual support, increases self-confidence, and motivation for self-care in chronic respiratory diseases [Citation35]. The benefits of counselling and community group activities in addition to attending pulmonary rehabilitation programmes for improving social participation in individuals with COPD on LTOT should be explored in future investigations.

Individuals with COPD frequently report symptoms of anxiety and depression. Better social participation was associated with fewer depression symptoms in individuals with COPD on LTOT. Unlike depression symptoms, anxiety was not associated with social participation, possibly because of a higher prevalence of depression in individuals with COPD [Citation36]. Social participation was also associated with better quality of life. Those with restricted social interaction may benefit from community support when referred to a social engagement community occupation and improving quality of life. Limited research on psychological intervention for improving social participation has been conducted in individuals with COPD, however, its beneficial effects are reported for improving self-efficacy and daily functioning [Citation37]. Importantly, when planning strategies to facilitate social participation, social networks that involve negative interactions should be addressed due to their negative effects on the overall health of individuals with physical disabilities. Examples of negative social interaction may include discounting, lack of understanding, criticism, and negative partner support [Citation38]. Although associations between social participation and modifiable outcomes of individuals with COPD on LTOT were observed in this study, the lack of a comparator group without LTOT prevent definite conclusions whether these findings are primary to patients on LTOT affected by the oxygen equipment, including long tubing, dependence on concentrators and electricity availability, stationary oxygen sources and battery life, stigma or by the impaired clinical status individuals with severe COPD may present with, but not directly related to LTOT.

This study has limitations. First, this was a convenience sample of individuals with COPD on LTOT assisted by the public health system. The level of social participation observed may not represent LTOT users assisted in private health who tend to have better socioeconomic status and easier access to specialised health care focussed on improving mobility in LTOT users [Citation39]. Second, factors related to social participation was investigated only in individuals with clinically stable COPD on LTOT. Future studies investigating the effects of acute exacerbation on social participation is required, particularly during a post hospitalisation period. Third, the LIFE-H questionnaire is a generic questionnaire for in-person community social participation assessment, not addressing the social participation using virtual and social media, including electronic forums, mobile applications or any remote contact. Future studies using recent COPD-specific validated instruments [Citation40] and assessment of social participation using virtual and social media, may further understanding the specific aspects of social participation and verify whether a shift to maintaining social participation via the use of virtual media also influence clinical outcomes in COPD.

Conclusion

The modifiable factors of dyspnoea, exercise capacity and muscle strength are associated with social participation in individuals with COPD on LTOT. Social participation restriction may lead to more depression symptoms and worsening of quality of life in this population. These findings suggest social participation as a valuable component of an individual’s assessment in rehabilitation programs. Strategies to promote in-person social support and social integration for individuals with COPD on LTOT should be explored further in future research.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the invaluable contribution of participants and staff members of the Department of Home Care (DID) and the Support Center for Disabled People - Dr Octavio Soares (CADEF).

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests or personal relationships related to or influencing the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) [Internet]. 2021. Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org/.

- Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006;3(11):e442. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442

- Spruit MA, Singh SJ, Garvey C, ATS/ERS Task Force on Pulmonary Rehabilitation, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitation . Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(8):e13–e64. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201309-1634ST Erratum in: Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014 Jun 15;189(12):1570. PMID: 24127811.

- Wells JM, Estepar RS, McDonald MN, COPDGene Investigators, et al. Clinical, physiologic, and radiographic factors contributing to development of hypoxemia in moderate to severe COPD: a cohort study. BMC Pulm Med. 2016;16(1):169. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-016-0331-0.

- Cani KC, Matte DL, Silva IJCS, et al. Impact of home oxygen therapy on the level of physical activities in daily life in subjects with COPD. Respir Care. 2019;64(11):1392–1400. DOI:https://doi.org/10.4187/respcare.06206

- Williams V, Bruton A, Ellis-Hill C, et al. What really matters to patients living with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? An exploratory study. Chron Respir Dis. 2007;4(2):77–85. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/1479972307078482.

- Levasseur M, Richard L, Gauvin L, et al. Inventory and analysis of definitions of social participation found in the aging literature: proposed taxonomy of social activities. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(12):2141–2149. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.09.041.

- Li YP, Lin SI, Chen CH. Gender differences in the relationship of social activity and quality of life in community-dwelling Taiwanese elders. J Women Aging. 2011;23(4):305–320. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/08952841.2011.611052. Erratum in: J Women Aging. 2012 Jan;24(1):94. PMID: 22014220.

- Bu F, Philip K, Fancourt D. Social isolation and loneliness as risk factors for hospital admissions for respiratory disease among older adults. Thorax. 2020;75(7):597–599. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2019-214445.

- Furlanetto KC, Pitta F. Oxygen therapy devices and portable ventilators for improved physical activity in daily life in patients with chronic respiratory disease. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2017;14(2):103–115. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/17434440.2017.1283981.

- Arnold E, Bruton A, Donovan-Hall M, et al. Ambulatory oxygen: why do COPD patients not use their portable systems as prescribed? A qualitative study. BMC Pulm Med. 2011;11:9. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2466-11-9

- Watz H, Pitta F, Rochester CL, et al. An official European respiratory society statement on physical activity in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(6):1521–1537. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00046814

- Michalovic E, Jensen D, Dandurand RJ, et al. Description of participation in daily and social activities for individuals with COPD. COPD. 2020;17(5):543–556. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/15412555.2020.1798373.

- Adams KB, Leibbrandt S, Moon H. A critical review of the literature on social and leisure activity and wellbeing in later life. Ageing Soc. 2011;31(4):683–712. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X10001091

- Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, STROBE initiative, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(8):W163–94. DOI:https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010-w1.

- Graham BL, Steenbruggen I, Miller MR, et al. Standardization of spirometry 2019 update. An official American thoracic society and European respiratory society technical statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(8):e70–e88. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201908-1590ST.

- Sociedade Brasileira de Pneumologia e Tisiologia. Diretrizes Para teste de função pulmonar. J Pneumol. 2002;28(3):S1–S238.

- Noreau L, Desrosiers J, Robichaud L, et al. Measuring social participation: reliability of the LIFE-H in older adults with disabilities. Disabil Rehabil. 2004;26(6):346–352. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280410001658649.

- Assumpção FSN, Faria-Fortini I, Basílio ML, et al. Adaptação transcultural do LIFE-H 3.1: um instrumento de avaliação da participação social [cross-cultural adaptation of LIFE-H 3.1: an instrument for assessing social participation]. Cad Saude Publica. 2016;32(6)S0102-311X2016000604001 [Portuguese]. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00061015.

- Raymond K, Auger L-P, Cormier M-F, et al. Assessing upper extremity capacity as a potential indicator of needs related to household activities for rehabilitation services in people with myotonic dystrophy type 1. Neuromuscul Disord. 2015;25(6):522–529. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nmd.2015.03.015.

- Kovelis D, Segretti NO, Probst VS, et al. Validation of the modified pulmonary functional status and dyspnoea questionnaire and the medical research council scale for use in Brazilian patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Bras Pneumol. 2008;34(12):1008–1018. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1590/s1806-37132008001200005.

- Pessoa BV, Arcuri JF, Labadessa IG, et al. Validity of the six-minute step test of free cadence in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Braz J Phys Ther. 2014;18(3):228–236. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1590/bjpt-rbf.2014.0041.

- Arcuri JF, Borghi-Silva A, Labadessa IG, et al. Validity and reliability of the 6-minute step test in healthy individuals: a cross-sectional study. Clin J Sport Med. 2016;26(1):69–75. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1097/JSM.0000000000000190.

- Reis MM, Arantes PMM. Assessment of hand grip strength – validity and reliability of the Saehan dynamometer. Fisioter Pesqui. 2011;18(2):176–181. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1590/S1809-29502011000200013

- Novaes RD, Miranda AS, Silva JO, et al. Equações de referência Para a predição da força de preensão manual em brasileiros de meia idade e idosos [reference equations for predicting of handgrip strength in Brazilian middle-aged and elderly subjects]. Fisioter Pesqui. 2009;16(3):217–222. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1590/S1809-29502009000300005

- Dowson C, Laing R, Barraclough R, et al. 2001. The use of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a pilot study. N Z Med J. 114(1141):447–449 [cited in: PubMed; PMID: 11700772].

- Wijkstra PJ, TenVergert EM, Van Altena R, et al. Reliability and validity of the chronic respiratory questionnaire (CRQ). Thorax. 1994;49(5):465–467. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.49.5.465.

- Schober P, Boer C, Schwarte LA. Correlation coefficients: appropriate use and interpretation. Anesth Analg. 2018;126(5):1763–1768. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000002864

- Field A. Discovering statistics. Using IBM SPSS statistics. Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publications; 2013.

- Goldbart J, Yohannes AM, Woolrych R, et al. ‘It is not going to change his life but it has picked him up’: a qualitative study of perspectives on long term oxygen therapy for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:124. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-11-124

- AlMutairi HJ, Mussa CC, Lambert CT, et al. Perspectives from COPD subjects on portable long-term oxygen therapy devices. Respir Care. 2018;63(11):1321–1330. DOI:https://doi.org/10.4187/respcare.05916.

- Faria-Fortini I, Polese JC, Faria CDCM, et al. Associations between walking speed and participation, according to walking status in individuals with chronic stroke. NRE. 2019;45(3):341–348. DOI:https://doi.org/10.3233/NRE-192805.

- Mazzarin C, Kovelis D, Biazim S, et al. Physical inactivity, functional status and exercise capacity in COPD patients receiving home-based oxygen therapy. COPD. 2018;15(3):271–276. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/15412555.2018.1469608.

- Young P, Dewse M, Fergusson W, et al. Respiratory rehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: predictors of nonadherence. Eur Respir J. 1999;13(4):855–859. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.13d27.x.

- Halding AG, Wahl A, Heggdal K. ‘Belonging’. ‘Patients’ experiences of social relationships during pulmonary rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(15):1272–1280. DOI:https://doi.org/10.3109/09638280903464471.

- Lacasse Y, Tan AM, Maltais F, et al. Home oxygen in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197(10):1254–1264. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201802-0382CI.

- Jonkers CC, Lamers F, Bosma H, et al. The effectiveness of a minimal psychological intervention on self-management beliefs and behaviors in depressed chronically ill elderly persons: a randomized trial. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24(2):288–297. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610211001748.

- Tough H, Siegrist J, Fekete C. Social relationships, mental health and wellbeing in physical disability: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):414. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4308-6 Erratum in: BMC Public Health. 2017 Jun 16;17 (1):580.

- Castanheira CH, Pimenta AM, Lana FC, et al. Utilization of public and private health services by the population of Belo Horizonte. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2014;17 Suppl 1 (Suppl 1):256–266. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1590/1809-4503201400050020.

- O’Hoski S, Richardson J, Kuspinar A, et al. A brief measure of life participation for people with COPD: validation of the computer adaptive test version of the late life disability instrument. COPD. 2021;18(4):385–392. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/15412555.2021.1934821.