Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) remains a compelling cause of morbidity and mortality; however, it is underestimated and undertreated in Brazil. Using multiple causes of death data from the Information System on Mortality, we evaluated, from 2000 to 2019, national proportional mortality; trends in mortality rates stratified by age, sex, and macro-region; and causes of death and seasonal variation, considering COPD as an underlying and associated cause of death. COPD occurred in 1,132,968 deaths, corresponding to a proportional mortality of 5.0% (5.2% and 4.7% among men and women), 67.6% as the underlying, and 32.4% as an associated cause of death. The standardized mortality rate decreased by 25.8% from 2000 to 2019, and the underlying, associated, male and female, Southeast, South, and Center-West region deaths revealed decreasing standardized mortality trends. The mean age at death increased from 73.2 (±12.5) to 76.0 (±12.0) years of age. Respiratory diseases were the leading underlying causes, totaling 69.8%, with COPD itself reported for 67.6% of deaths, followed by circulatory diseases (15.8%) and neoplasms (6.24%). Respiratory failure, pneumonia, septicemia, and hypertensive diseases were the major associated causes of death. Significant seasonal variations, with the highest proportional COPD mortality during winter, occurred in the southeast, south, and center-west regions. This study discloses the need and value to accurately document epidemiologic trends related to COPD in Brazil, provided its burden on mortality in older age as a significant cause of death, aiming at effective planning of mortality prevention and control.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is defined by the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) document as a common, preventable, and treatable disease characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitation that is usually progressive and associated with an enhanced chronic inflammatory response in the airways and lungs due to significant exposure to noxious particles or gases [Citation1]. COPD is a compelling cause of morbidity and mortality, but is still largely underdiagnosed and undertreated in Brazil. Data from the Platino Study showed a prevalence of 15.8% in adults over 40 years of age. Nevertheless, only 0.8% of patients have a clinical diagnosis of COPD [Citation2]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis disclosed the prevalence of COPD in Brazil in 17% in adults over 40 years of age (95% CI: 13–22; I2 = 94%) [Citation3].

In the last two decades, aging of the population has contributed to the increased prevalence of COPD, while reduction in smoking and advances in its treatment may have attenuated its mortality [Citation4,Citation5]. As a disease prevalent in the elderly and a common cause of mortality, the evaluation of multiple causes of death can be a useful source of information on diseases and morbidity related to COPD mortality and the burden of COPD as associated with other fatal diseases.

Brazil, officially named the Federative Republic of Brazil, is the world’s fifth largest country, covering a total territory of 8.5 million km2, and the sixth largest population, estimated at 213 million inhabitants in 2021. The country is politically and administratively divided into 27 federated units (26 states and the Federal District) and 5,570 municipalities. The 27 federated units are grouped into five geographic macro-regions: north, northeast, southeast, south, and central-west. A large country with regional differences and demographics needs a comprehensive study of COPD mortality trends.

This study aimed to evaluate mortality related to COPD in Brazil over the last 20 years using multiple-cause-of-death methodology to assess trends in mortality for different regions of Brazil, difference between sex mortality, and seasonal mortality variation. A detailed assessment of COPD mortality and its association with other causes of death is a major step in understanding COPD demographics in Brazil and a fundamental tool aiding the development of public health projects that impact this disease.

Methods

The annual mortality data were extracted from the public multiple-cause-of-death databases of the Mortality Information System (Sistema de Informações Sobre Mortalidade, SIM) located at the Brazilian Unified Health System Information Technology Department (Departamento de Informática do Sistema Único de Saúde, DATASUS), Ministry of Health (MS) [Citation6]. The 540 mortality datasets (one for each of the 27 federative units over 20 years) were merged into a single database file. All deaths were included in which COPD as a cause of death was listed on any line or in either part of the WHO International Form of Medical Certificate of Cause-of-Death (the medical certification section of the death certificate), irrespective of whether they were characterized as the underlying cause of death (UCOD) or as an associated (non-underlying) cause. Complications of the underlying cause (part I of the medical certification section) and contributing causes (part II of the medical certification section) were jointly designated as associated (non-underlying) causes of death [Citation7]. We employed the 2000–2019 mid-year estimates of the population for Brazil, discriminated by year, sex, age group, and Brazilian regions.

According to the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10), COPD as a cause of death rubrics included three character categories codes J40 bronchitis, not specified as acute or chronic; J41 simple and mucopurulent chronic bronchitis; J42 unspecified chronic bronchitis; J43 emphysema, J44 other chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases; and J47 bronchiectasis [Citation8].

To reconstruct the morbid process leading to death, all causes of death listed in the medical certification section of the death certificate were considered, including those classified as ill-defined, equated as such, or considered by the World Health Organization (WHO) as modes of death [Citation7,Citation8].

Records included in the mortality databases contain fields such as those appearing on the official Brazilian death certificate. In addition, we created auxiliary fields for the study of multiple causes, including a field designed to contain a single “string” of characters composed of the conditions entered on lines (a), (b), (c), and (d) of part I and part II of the medical certification section of the death certificate.

The causes of death were automatically processed using the Underlying Cause Selector software (Seletor de Causa Básica - SCB) [Citation9]. Automatic processing involves the use of algorithms and decision tables that incorporate the WHO mortality standards and etiological relationships among the causes of death. The expressions “death from” and “death due to” refer to the UCOD, whereas “deaths with a mention of” and “mortality related to” refer to the listing of a given condition either as the underlying cause or as an associated cause. The causes of death evaluated in the present study were those mentioned in the medical certification section, which are known internationally as “entity axis codes” defined and presented under the structure and headings of the ICD [Citation10].

Using mortality rates, proportions, and historical trends, we studied the distributions of the following variables: sex, age at death (in five-year age groups), year of death, underlying cause of death, associated (non-underlying) cause(s) of death, total mentions of each cause of death, mean number of causes listed per death certificate, seasonal variation of deaths, and geographical distribution of deaths. For seasonal analysis, comparison of proportional mortality was related to the seasonal distribution of overall Brazilian deaths and were grouped as follows: summer, December 21st to March 20th; autumn, March 21st to June 20th; winter, June 21st to September 20th; and spring, September 21st to December 20th. Medical and demographic variables were processed using the following software: dBASE III Plus, version 1.1 and dBASE IV (Ashton-Tate Corporation, Torrance, CA), and Epi Info, version 6.04d (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA), in emulated dbDOS ™ PRO 6 environment, Excel 2016 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA). We used the Multiple Causes Tabulator (Tabulador de Causas Múltiplas for Windows) program (DATASUS, Ministério da Saúde, Faculdade de Saúde Pública, Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil), processing codes for ICD-10 (TCMWIN, version 1.6), in our presentation of the associated causes and of the mean number of causes per death certificate [Citation11].

For the presentation of the associated causes listed on the death certificates on which COPD was identified as the underlying cause, we prepared special lists showing the causes involved in the respective natural histories, as well as those mentioned with the greatest frequency. The duplication or multiplication of causes of death was avoided when these are presented in the abbreviated lists. The number of causes depends on the breadth of the class (subcategory, category, grouping, or chapter of the ICD-10); therefore, if two or more causes mentioned in the medical certification section were included in the same class, only one cause was computed [Citation9,Citation10].

Mortality rates (per 100,000 population) for COPD were calculated by year and for the study period (2000–2019) as a whole, based on the number of deaths that had been identified as the underlying cause or as an associated cause, as well as on the overall number of mentions. To calculate the average mortality rate, the overall number of deaths was divided by the sum of the respective annual population counts for the 20-year study period.

The Programa para Análisis Epidemiológico de Datos (Epidat, Epidemiological Analysis of Data Program), version 4.2 (Dirección Xeral de Innovación e Xestión da Saúde Pública, Xunta de Galicia: http://dxsp.sergas.es, and Pan American Health Organization), was used to standardize, by the direct method, the sex and age-adjusted crude and average mortality rates for the study period as a whole, to the new WHO Standard Population [Citation12]. Crude and standardized rates were calculated according to the 5-year age groups.

We used analysis of variance to compare the mean number of causes mentioned on the death certificate, the Kruskal–Wallis H test to compare the mean age at death between groups, and chi-square goodness-of-fit test to analyze the uniformity within the seasonal distribution of COPD deaths. The Joinpoint Regression Program, version 4.9.0.0, was used to evaluate the changes in age-standardized rate trends [Citation13]. Assuming a Poisson distribution, joinpoint analysis chooses the best fitting point (or points), at which the rate increases or decreases significantly and calculates the annual percent change and average annual percent change. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

The study was waived by the author’s institutional review boards because it exclusively uses large public domain national mortality databases of secondary data that are anonymous, without nominal personal identification, and therefore carries no individual risk whatsoever. The ethical principles contained in the Resolution of the National Health Council (CNS) n. 466 of December 12, 2012 were observed.

Results

Among the 22,663,091 deaths that occurred from 2000 to 2019 in Brazil, 1,132,968 had COPD mentioned as a cause of death in their death certificate, corresponding to a total proportional mortality of 5.0% (5.2% for men and 4.7% for women). displays the proportional age distribution of deaths related to COPD. Higher percentages were found in the four age groups from 65 years to 80 years and older (6.6%, 7.7%, 8.2%, and 7.2%). The proportional mortality in macro-regions was 3.7% in the north, 3.0% in the northeast, 5.0% in the southeast, 8.1% in the south, and 6.5% in the center-west.

Table 1. Age stratification of Brazilian deaths, COPD all mention, underlying cause and non-underlying cause of deaths, Brazil, 2000–2019.

Of the 1,132,968 overall deaths mentioning COPD, it was identified as the underlying cause in 765,849 (67.6%) and in 367,119 (32.4%) as an associated (non-underlying) cause of death (). Similar close values of COPD as the underlying cause occurred throughout the years during the entire study period, age strata, sexes, Brazilian states, and regions. Thus, when mentioned in death certificates, COPD was selected as the underlying cause in 66.3% of males and in 69.5% of females, ranging from 57.9% among ages 5–9 years to 70.8% among 80 years and older, 62.3% in the Federal District to 75.5% in the state of Maranhão, and from 66.9% in the South to 72.5% in the North region.

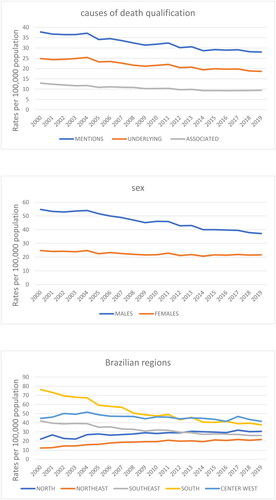

Mortality rates and trends for the period 2000–2019 are presented in and . Overall, all-mentions standardized mortality rate decreased to 25.8% from 37.79 per 100.000 in 2000 to 28.06 per 100.000 in 2019. Considering the entire country, underlying, associated, and all mentions, male and female deaths revealed decreasing standardized mortality trends. Dividing in regions, there was a reduction in mortality in the southeast, south, and center-west regions, while increasing trends were observed in the north and northeast regions. Higher standardized mortality rates occurred among men and in the center-west, south, and southeast regions. Decreasing male trends was more pronounced than that of females. Overall, the mortality male/female death ratio was 1.5, but decreased from 1.7 in 2000 to 1.2 in 2017, while the overall male/female standardized mortality rates were 2.0, but also decreasing from 2.2 in 2000 to 1.7 in 2019.

Figure 1. COPD standardized mortality rates according to cause of death qualification, sex, and Brazilian regions, Brazil, 2000–2019.

Table 2. Average age-adjusted mortality rates and annual percent change trends related to COPD by cause of death. Brazil, 2000 – 2019.

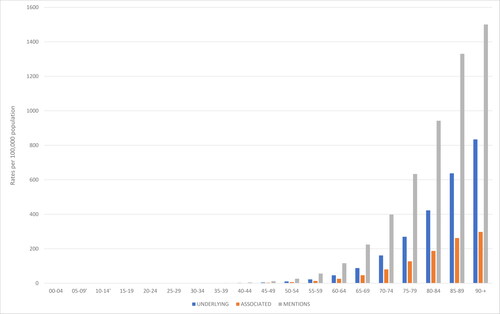

COPD deaths were observed in all age groups; nonetheless, 90% occurred after 57 years of age and increased exponentially in the following older strata groups (). For the entire period, the overall mean and median ages at death were 74.8 (±12.4) and 76.5 (67.5–83.5) for all mentions, 75.4 (±12.3) and 76.5 (68.5–84.5) for underlying cause, 73.6 (±12.5) and 75.5 (66.5–82.5) for associated causes, 74.3 (±12.1) and 75.5 (67.5–82.5) for males, and 75.5(±12.8) and 77.5 (68.5–84.5) for female deaths. Since 2000 to 2019, the mean and median ages at death increased from 73.2 (±12.5) and 74.5 (66.5–81.5) to 76.0 (±12.0) and 77.5 (68.5–84.5) years of age (p = 0.000000).

Figure 2. COPD-specific averaged mortality rates according to the cause of death qualification and age, Brazil, 2000–2019.

The underlying causes of the 1,132,968 death certificates in which COPD was listed as a cause of death in men and women are presented in and sorted in descending order according to the ICD-10 chapter systematic code structure. Overall, diseases of the respiratory system are the leading underlying cause, totaling 69.8%, with COPD itself reported in 67.6% of deaths. Next, the ICD chapter on diseases of the circulatory system emerges, totaling 15.8%, followed by neoplasms, with 6.24% of all deaths. The main underlying causes of circulatory diseases were ischemic heart, cerebrovascular, and hypertensive diseases, and among the neoplasms, respiratory and intrathoracic (bronchus and lung 89.0%) and digestive organ sites prevailed. Tuberculosis, diabetes mellitus, renal failure, Alzheimer’s disease, and accidental fall deaths stand out among the infectious, metabolic, genitourinary, nervous system, and external causes of death, respectively. Tuberculosis, neoplasms of digestive and respiratory organs, alcohol disorders, ischemic heart diseases, and aortic aneurysms predominate among men and diabetes, hypertensive diseases, and COPD among women.

Table 3. Underlying causes of death that listed COPD in death certificates among males and females, Brazil, 2000–2019.

The leading associated (non-underlying) causes of deaths listed on death certificates in which the underlying causes were COPD and other selected conditions for the period 2000–2019 are displayed in descending order for overall deaths (). Unquestionably, respiratory failure, occurring in 44%, 26%, and 38% of patients with COPD, other, and total underlying causes, stand out as the main associated causes. Pneumonia and septicemia with COPD as the underlying causes, while hypertensive disease and pneumonia with other underlying causes, followed respiratory failure. The use of tobacco was mentioned in 9% of all deaths. The crude mean number of causes per death certificate observed among COPD, other selected underlying cause deaths, and averaged total deaths were 3.5 (±1.23), 4.3 (±1.27), and 3.76 (±1.3), respectively.

Table 4. Leading associated (non-underlying) causes on death certificates in which COPD was identified as the underlying cause (UC) or as an associated (non-underlying) cause, and total, Brazil, 2000–2019.

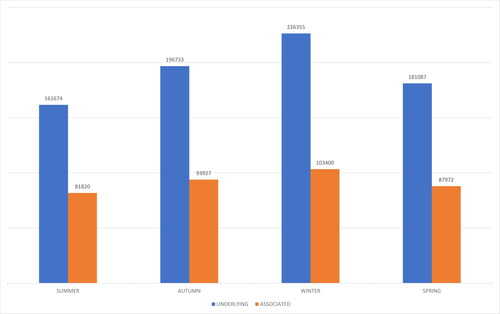

The seasonal variations in COPD identified as causes of death are shown in and . Significant seasonal variations, with the highest proportional mortality during winter, occurred in all-mentions deaths (x2 351.81, df 3, p = 0.000001), underlying cause of death (x2 193.68, df 3, p = 0.000001), and associated causes of death (x2 11.70, df 3, p =< 0.0001), as well as for male deaths (x2 215.69, df 3, p = 0.000001) and female deaths (x2 126.26, df 3, p = 0.000001). Similarly, significantly higher winter proportional mortality was observed in the southeast region (x2 134.01, df 3, p = 0.000001), south region (x2 375.26, df 3, p = 0.000001), and center-west region (x2 10.53, df 3, p = 0.000001), while in the north and northeast regions, nonsignificant proportional mortality prevailed.

Figure 3. Number of deaths related to COPD, according to cause of death qualification and seasons of the year, Brazil, 2000–2019.

Table 5. Brazilian and COPD deaths, proportional mortality (PM) related to COPD according to season of the year and qualification or the cause of death, Brazil, 2000–2019.

Discussion

This study describes the mortality related to COPD in Brazil in the last 20 years using the multiple-cause-of-death methodology, considering all its mentions as cause of death on death certificates. Of course, the benefits of this approach include contemplating all death certificates in the whole country where COPD was listed and not only as the underlying cause of death. Consequently, it was possible to consider the advice of previous studies to overcome the underestimation of COPD as the underlying cause of death [Citation14–22]. In the period 2000–2019, COPD was identified as the underlying cause of death in 67.6% of deaths in which it was listed due to its fatality. While not comparable owing to differences in methodology, other studies have shown further results. Accordingly, among all listed in death certificates, COPD occurred as UCOD in the United States, 43.3% in 1979–1993 [Citation14], 42.3% in 1993 [Citation15], and 48.89% and 50.34% in 1999 and 2015, respectively [Citation21]; in England and Wales, 59.8% in 1993–1999 [Citation16]; in France, 47.8% in 2000–2002 [Citation18] and 44.8% in 2006 [Citation23]; in the Yangpu district of Shanghai, China, 68.4% in 2003–2011 [Citation19]; in the Veneto Region (northeastern Italy), 34% in 2008–2012 [Citation20]; and in Galicia, Spain, 57.9% in 2015–2017 [Citation22]. Some facts are cited to elucidate these differences. Comorbidities and death certification were considered better recorded in the USA than in England, where inadequate training of doctors has been documented, along with the influence of the severity and treatment of COPD [Citation16]. Likewise, the differences in studies using the ICD-9 and ICD-10 coding rules are difficult to address and consider international comparisons [Citation19]. In addition, the patterns of death certification rely on the population’s age distribution and the associated increase in chronic comorbid diseases without a common etiologic factor, rendering it difficult to decide regarding the impact of COPD on deaths [Citation20]. In Brazil, the severity and fatality of COPD explain the UCOD levels found in this study.

Regrettably, the underestimation of COPD as a cause of death does not rely only on underreporting it as the underlying cause in death certificates. COPD-related mortality is also underestimated due to under-diagnosis and under-recognition as a cause of death and underlying or non-underlying, among the deaths of COPD patients, even with severe GOLD stages [Citation1]. For instance, in a population-based COPD cohort, over ten years of follow-up, among the 45% of deaths, COPD was recorded in only 28.2% of the death certificates, of which 50% was the underlying or an associated cause of death. The lack of COPD in death certificates was correlated with male sex and being overweight or obese [Citation24]. In the city of Belo Horizonte, the capital of the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil, in 2017, an evaluation of the profile of hospital deaths certified with ill-defined or garbage codes as the underlying cause of death verified that the proportional mortality due to COPD increased from 3.8% to 4.5% after investigation. Of the original deaths reported as pneumonia, 10.3% were reclassified as COPD. The authors emphasize the importance of continuous physician training in cause of death certifications [Citation25].

A previous study has shown that from 1980 to 1998, the number of deaths in Brazil due to COPD as UCOD increased significantly by 3.3-fold in the whole country and higher rates were found in the south and southeast regions [Citation17]. However, a subsequent study verified a considerable decline in COPD mortality rates in Brazil, as well for all respiratory UCOD from 1996 to 2008 in both sexes, where figures suggest the initial change of trends after 1998 [Citation26]. An ensuing analysis verified that the general UCOD mortality rates due to COPD in Brazil showed an increasing trend from 1989 to 2004 and decreased thereafter over 2009, including both sexes. The south and southeast regions showed the highest COPD mortality rates with increasing trends until 2001–2002 and then decreased, whereas the north, northeast, and central-west regions showed lower mortality rates but increasing trends [Citation27]. A recent study considering the period 2000–2016 concluded that in Brazil, there was a significant downward trend in the UCOD mortality for both sexes and in all age groups [Citation28]. The latest reviewed paper considered the ICD-10 category J44 to analyze COPD in adults aged ≥ 40 years in Brazil from 2010 to 2018 and concluded that the UCOD crude mortality rates are heterogeneous and have not decreased overall, and the declined rates in the southeast and south regions and increased rates in the north, northeast, and center-west regions were verified [Citation29]. This is partially explained by uneven access to treatment between different regions. Several states have COPD care guidelines different from the Union Health Ministry’s protocol. In addition, COPD care has changed over the past two decades regarding pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic treatment. The availability of different treatments vary significantly between the states in Brazil. It is reasonable to infer that these differences in mortality trends are associated with regional inequalities [Citation30].

An international study on trends in COPD mortality from 1995 through 2017, including 24 countries (six in Latin America and the Caribbean, two in North America, Asia and Oceania, and 12 in Europe), concluded that UCOD mortality rates declined in most countries, remained stable in females in North America, and increased in six countries in Europe [Citation31]. The latest studies on COPD multiple causes of death show that in the Yangpu district of Shanghai, China, 2003–2011, a significant decreasing trend of age-standardized rates of death was observed in both men and women [Citation19]. In the Veneto region in Italy, death rates decreased between 2008 and 2011 in men, and lesser in women, followed by a minimal increase in 2012 due to a cold spell in Italy [Citation20]. In the United States of America, in 1999–2015, mortality rates decreased among men but continued to increase among women [Citation21,Citation32]. In the current analysis of trends in COPD-related mortality in Brazil, an overall yearly decrease during 2000–2019 was verified. One of the main reasons for this decrease was the reduction in tobacco smoking, which remains as the most important risk factor for COPD [Citation33]. Surveillance of risk and protective factors for chronic diseases by telephone revealed the prevalence of smokers in adults (≥ 18 years) in Brazilian state capitals and Federal District as 9.8%, 12.3% and 7.7%, respectively, for the overall, male, and female population in 2019, as well as an overall decline of 37.6% from 2006 to 2019 [Citation34]. The Global Burden of Disease Study 2015 revealed that Brazil was included among the 13 countries that recorded significant annualized rates of decline between 1990 and 2005 and 2005 and 2015, suggesting sustained progress in tobacco control. Among the countries with the largest number of total smokers in 2015, Brazil recorded the largest overall reduction in prevalence for both male and female daily smoking, which dropped by 56.5% (51.9–61.1) and 55.8% (48.7–61.9), respectively, between 1990 and 2015 [Citation4].

The causes of death also mentioned simultaneously with COPD in death certificates are crucial factors responsible for the demise. Sometimes described as comorbidities, an ordinary and descriptive enumeration follows, and their character appears regularly to be unqualified. Hence, this study presents a consequent analysis of over 20 years of mortality of 1,132,968 deaths comprising the mean number of 3.5 and 4.3 causes per death certificate for COPD and other listed UCOD, both of which were analyzed as the underlying cause and reported with their associated causes of death. It is evident that COPD, among respiratory diseases, stands as its own and a specific major UCOD and in Brazil at higher rates when compared with other countries. Furthermore, circulatory system diseases, neoplasms, chronic conditions, and falls, as regular causes of death in the older age population, respond to UCOD in milder COPD events. Concomitantly, respiratory failure, pneumonia, septicemia, and hypertensive diseases, as associated (non-underlying) causes, occur with COPD and other underlying causes.

A significant seasonal variation was observed in the country for COPD overall mentioned deaths and underlying and associated causes, characterized by higher mortality during winter periods. This variation was also better defined in the Southeast and South regions, where seasonal climatic variations were more distinct. In A Coruña, Spain, in 1997–1998, a one-year study concluded that a clear winter seasonal variation was observed in the number of patients requiring admission due to COPD exacerbations [Citation35]. In France, in 2000–2006, important seasonal variations were observed, with a clear prevalence of deaths related to COPD during winter [Citation18]. In the Yangpu district of Shanghai, China, in 2003–2011, a significant seasonal winter variation occurred in deaths identified with underlying causes of chronic bronchitis, other obstructive pulmonary diseases, and asthma [Citation19]. In Lima, Peru, a study verified the occurrence of a higher frequency of COPD-related deaths in winter and spring [Citation36]. In the Veneto region (northeastern Italy), in 2008–2012, deaths related to COPD showed a pronounced seasonal variability, where the ratio between the number of deaths in January to March (cold season) and those in July to September (warm season) was 1.2 for all causes, 1.50 when COPD was mentioned in a death certificate, and 1.8 when COPD was identified as UCOD. Moreover, the proportional mortality ranged from 2.2% in the warm season to 3.3% in the cold season in the UCOD analysis and from 7.1% to 8.9% in the all-mentions analysis [Citation20]. In the United States, a retrospective analysis using the 2016 National Impatient Sample and National Impatient Database highlighted the dramatic seasonal variation in rates of admission and mortality for COPD exacerbation during the coldest months of January, February, and March [Citation37]. Increased blood pressure levels, arterial spasm, and pulmonary disease exacerbations due to respiratory viruses are far more common in winter, and passive smoking in colder weather can explain this pattern, which has also been observed in other cardiovascular conditions such as cerebral and coronary ischemia.

Population mortality statistics are subject to both qualitative and quantitative problems. Underdiagnosis and under-recognition of COPD as a cause of death is a significant issue, as discussed in previous paragraphs. In Brazil, death certificates conform to WHO recommended form and physicians should complete cause of death attending to civil registration law. Causes of death comprised in mortality statistics are recorded, coded, and interpreted by means of ICD standards. Trained nosologists formally translate medical causes of death into ICD codes. Automatic processing of causes of death and mortality data follows international agreed practices. Critical quality control measures permeate throughout all stages of mortality statistics. A recent evaluation of multiple causes of death statistics in Brazil, from 2003 to 2015, verified an increase in crude mean number of causes per death certificate from 2.81% to 3.02% (7.5%), a decrease in certificates of death with only one cause mentioned from 20.32% to 13.75%, and an additional decrease of ill-defined causes of death as underlying cause from 12.95% to 5.59% (56.22%) [Citation38,Citation39].

Conclusions

Our study revealed that the weight of COPD proportional mortality in Brazil is one of the leading causes of death in most densely populated regions. The importance of COPD as an underlying cause of death is compared with ischemic cardiovascular disease, cancer, and diabetes in the elderly. As COPD is an underdiagnosed and underreported disease, its impact is even greater. Although the use of multiple causes of death methodology recovered non-underlying causes and adjusted the mortality underestimation, the number of deaths is undoubtedly larger than that verified owing to underreporting and underdiagnosis. This study found a decreasing standardized mortality trend and increasing age at death in the developed regions, whereas it increased COPD mortality in less-developed regions. A decentralized COPD care strategy is needed in a country of continental dimensions with marked socioeconomic differences between regions. Persistence of successful tobacco control efforts and handling of environmental and occupational exposures are essential for prevention, as well as training physicians in the diagnosis, treatment, and reporting of COPD.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The author(s) reported there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

References

- Patel AR, Patel AR, Singh S, et al. Global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease: the changes made. Cureus. 2019;11(6):e4985. DOI:10.7759/cureus.4985.

- Menezes AMB, Jardim JR, Pérez-Padilla R, et al. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and associated factors: the PLATINO Study in São Paulo, Brazil. Cad Saude Publica. 2005;21(5):1565–1573. DOI:10.1590/s0102-311x2005000500030

- Cruz MM, Pereira M. Epidemiology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Brazil: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cien Saude Colet. 2020;25(11):4547–4557. DOI:10.1590/1413-812320202511.00222019.

- GBD 2015 Tobacco Collaborators. Smoking prevalence and attributable disease burden in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2017;389(10082):1885–1906. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30819-X

- Li X, Cao X, Guo M, et al. Trends and risk factors of mortality and disability adjusted life years for chronic respiratory diseases from 1990 to 2017: systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. BMJ. 2020;368:m234.

- Ministério da Saúde. Departamento de Informática do SUS. Acesso à Informação. Serviços. transferência-download-de-arquivos. arquivos-de-dados. Available from Transferência de Arquivos – DATASUS (saude.gov.br)

- World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. Tenth revision. Vol. 2. Instruction manual. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1993.

- World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. Tenth revision. Vol. 1. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1993.

- Santo AH, Pinheiro CE. Uso do microcomputador na seleção da causa básica de morte [The use of the microcomputer in selecting the basic cause of death]. Bol la of Sanit Panam. 1995;119(4):319–327.

- Santo AH. Causas múltiplas de morte: formas de apresentação e métodos de análise [Multiple causes of death: presentation forms and analysis methods] [Tese de Doutorado]. São Paulo: Faculdade de Saúde Pública, Universidade de São Paulo; 1988.

- Santo AH, Pinheiro CE. Tabulador de causas múltiplas de morte [Multiple causes-of-death tabulator]. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 1999;2(1-2):90–97. DOI:10.1590/S1415-790X1999000100009

- Ahmad OB, Boschi-Pinto C, Lopez AD, et al. Age standardization of rates: a new WHO standard. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2001.

- Joinpoint Regression Program, Version 4.7.0.0. February 2019; Statistical Research and Applications Branch, National Cancer Institute.

- Mannino DM, Brown C, Giovino GA. Obstructive lung disease deaths in the United States from 1979 through 1993. An analysis using multiple-cause mortality data. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156(3 Pt 1):814–818. DOI:10.1164/ajrccm.156.3.9702026

- Meyer PA, Mannino DM, Redd SC, et al. Characteristics of adults dying with COPD. Chest. 2002;122(6):2003–2008. DOI:10.1378/chest.122.6.2003

- Hansell AL, Walk JA, Soriano JB. What do chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients die from? A multiple cause coding analysis. Eur Respir J. 2003;22(5):809–814. DOI:10.1183/09031936.03.00031403

- Campos HS. Mortalidade por DPOC no Brasil, 1980-1998 [COPD mortality in Brazil, 1980-1998]. Pulmão. 2003;12(4):217–223.

- Fuhrman C, Jougla E, Nicolau J, et al. Deaths from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in France, 1979-2002: a multiple cause analysis. Thorax. 2006;61(11):930–934. DOI:10.1136/thx.2006.061267.

- Cheng Y, Han X, Luo Y, et al. Deaths of obstructive lung disease in the Yangpu district of Shanghai from 2003 through 2011: a multiple cause analysis. Chin Med J (Engl). 2014;127(9):1619–1625.

- Marcon A, Saugo M, Fedeli U. COPD-related mortality and co-morbidities in northeastern Italy, 2008-2012: a multiple causes of death analysis. COPD J Chron Obstr Pulm Dis. 2016;13(1):35–41. DOI:10.3109/15412555.2015.1043427

- Obi J, Mehari A, Gillum R. Mortality related to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and Co-morbidities in the United States, a multiple causes of death analysis. COPD J Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2018;15(2):200–205. DOI:10.1080/15412555.2018.1454897

- Fernández-García A, Pérez-Ríos M, Fernández-Villar A, et al. Four decades of COPD mortality trends: analysis of trends and multiple causes of death. JCM. 2021;10(5):1117. DOI:10.3390/jcm10051117

- Fuhrman C, Delmas MC, Annesi-Maesano I, et al. Epidemiology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in France. Rev Mal Respir. 2010;27(2):160–168. DOI:10.1016/j.rmr.2009.08.003

- Lindberg A, Lindberg L, Sawalha S, et al. Large underreporting of COPD as cause of death-results from a population-based cohort study. Respir Med. 2021;186:106518. DOI:10.1016/j.rmed.2021.106518

- Corrêa PRL, Ishitani LH, Lansky S, et al. Change in the profile of causes of death after investigation of hospital deaths in Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 2017. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2019;22(Suppl 3):E190009.supl.

- Benseñor IM, Fernandes TG, Lotufo PA. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Brazil: mortality and hospitalization trends and rates, 1996-2008. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15(3):399–404.

- Graudenz GS, Gazotto GP. Mortality trends due to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Brazil. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992). 2014;60(3):255–261. DOI:10.1590/1806-9282.60.03.015

- Gonçalves-Macedo L, Lacerda EM, Markman-Filho B, et al. Trends in morbidity and mortality from COPD in Brazil, 2000 to 2016. J Bras Pneumol. 2019;45(6):e20180402.

- Silva D, Alemar MG, Martins F, et al. Chronic pulmonary disease (COPD) mortality in Brazil: 2010 to 2016: analysis. Valuein Health. 2020;23(Suppl 2):S727.

- Carvalho-Pinto RM, da Silva IT, Navacchia LYK, et al. Exploratory analysis of requests for authorization to dispense high-cost medication to COPD patients: the São Paulo “protocol. J Bras Pneumol. 2019;45(6):e20180355.

- Lortet-Tieulent J, Soerjomataram I, López-Campos JL, et al. International trends in COPD mortality, 1995-2017. Eur Respir J. 2019;54(6):1901791. DOI:10.1183/13993003.01791-2019

- Obi JI. COPD-related mortality and co-morbidities in the United States of America, 1999-2015: a multiple causes of death analysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:A3550.

- Bai JW, Chen XX, Liu S, et al. Smoking cessation affects the natural history of COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:3323–3328. DOI:10.2147/COPD.S150243

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de Análise em Saúde e Vigilância de Doenças Não Transmissíveis. Vigitel Brasil 2019: vigilância de fatores de risco e proteção para doenças crônicas nas capitais dos 26 estados brasileiros e no Distrito Federal em 2019. Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde, Departamento de Análise em Saúde e Vigilância de Doenças Não Transmissíveis, Brasília; Ministério da Saúde, 2020.

- De La Iglesia Martínez F, Pellicer Vázquez C, Ramos Polledo V, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and the seasons of the year. Arch Bronconeumol. 2000;36(2):84–89.

- Sasieta Tello HC, Watanabe Tejada LC, Dibu G, et al. Evidence of seasonal variation in COPD related deaths in the equatorial Southern hemisphere. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189.

- Chakraborti A, Ramanathan R, Alunilkummannil J. Seasonal variations in outcomes and costs for COPD. Chest. 2019;156(4):A1164. DOI:10.1016/j.chest.2019.08.1060

- Santo AH, Pinheiro CE. Reavaliação do potencial epidemiológico das causas múltiplas de morte no Brasil, 2015 [Reevaluation of the epidemiological multiple-cause-of-death potential use in Brazil, 2015]. Rease. 2022;8(1):1620–1639. DOI:10.51891/rease.v8i1.4008

- Santo AH, Pinheiro CE. Reassessment of the epidemiological multiple-cause-of-death potential use in Brazil, 2015. Presented at the Fourth International Meeting on Multiple Cause-of-Death Analysis, Institut National d’Etudes Démographiques, INED 2019; 2019 16–17 May; Paris.