Abstract

Background and objective

Triple therapy with an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS), a long-acting β2-agonist bronchodilator (LABA) and a long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) is recommended as step-up therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients who continue to have persistent symptoms and increased risk of exacerbation despite treatment with dual therapy. We sought to evaluate different treatment pathways through which COPD patients were escalated to triple therapy.

Methods

We used population health databases from Ontario, Canada to identify individuals aged 66 or older with COPD who started triple therapy between 2014 and 2017. Median time from diagnosis to triple therapy was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. We classified treatment pathways based on treatments received prior to triple therapy and evaluated whether pathways differed by exacerbation history, blood eosinophil counts or time period.

Results

Among 4108 COPD patients initiating triple therapy, only 41.2% had a COPD exacerbation in the year prior. The three most common pathways were triple therapy as initial treatment (32.5%), LAMA to triple therapy (29.8%), and ICS + LABA to triple therapy (15.4%). Median time from diagnosis to triple therapy was 362 days (95% confidence interval:331–393 days) overall, but 14 days (95% CI 12–17 days) in the triple therapy as initial treatment pathway. This pathway was least likely to contain patients with frequent or severe exacerbations (22.0% vs. 31.5%, p < 0.001) or with blood eosinophil counts ≥300 cells/µL (18.9% vs. 22.0%, p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Real-world prescription of triple therapy often does not follow COPD guidelines in terms of disease severity and prior treatments attempted.

Keywords:

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a progressive lung disease and a leading cause of mortality and morbidity worldwide [Citation1]. COPD is preventable and manageable through non-pharmacological and pharmacological treatment [Citation2].

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) and long-acting β2-agonist (LABA) are the three most common long-acting maintenance pharmacotherapies used for COPD patients [Citation3]. The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) strategy [Citation4], the American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline [Citation5], and the Canadian Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline on pharmacotherapy [Citation6] are among other documents that have been created to aid in effective management of this disease. Triple therapy (ICS, LABA and LAMA) has been recommended as a step-up therapy for patients who have persistent symptoms and increased risks of exacerbation despite treatment with ICS + LABA or LAMA + LABA combination therapies [Citation4,Citation6].

Studies have shown that real-world clinical use of triple therapy differs from international guidelines, with the majority of patients using triple therapy only having mild to moderate (as opposed to severe) disease [Citation7–10] . Inappropriate prescription of triple therapy, specifically the ICS component, exposes patients to heightened risk of pneumonia as well as other side effects, and places additional economic burden on individual patients and/or healthcare systems. Identifying real-life triple therapy prescription patterns can help identify where deviations from the guidelines occur. This information can be used to educate health care providers and patients on appropriate therapeutic options. Moreover, understanding prescription patterns of triple therapy in real life could help inform the conduct of future real-world observational studies on the effectiveness of triple therapy as well as the interpretation of their findings.

While previous studies have assessed how COPD triple therapy prescription compares to strategy document recommendations [Citation8–10] and the step-up of other long-acting inhaled medications to triple therapy [Citation11–15], studies examined the entire medication escalation pathways from diagnosis to triple therapy are rare. Our objectives were to describe how medication regimens in older people escalated over time to triple therapy and to evaluate how these prescriptions deviated from strategy document. We focus on triple therapy prescriptions after 2014, the year of introduction of LAMA/LABA combination medication in Ontario.

Material and methods

Study design

We conducted a retrospective, longitudinal observational study of the escalation of medication regimens from their initiation after COPD diagnosis to the start of triple therapy in older individuals with COPD, using healthcare administrative data from 2003 to 2017 from the province of Ontario, Canada. This project was approved by the Research Ethics Board of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Center, Toronto, Canada.

Data sources

Residents of Ontario have universal public health insurance under the Ontario Health Insurance Plan, the single payer for all medically necessary services across virtually all providers, and hospitals. Service details are captured in health administrative databases, which are held securely in coded form at ICES and can be linked on an individual level to provide a complete health services profile for each Ontario resident. ICES is an independent, nonprofit research institute whose legal status under Ontario’s health information privacy law allows it to collect and analyze health care and demographic data, without consent, for health system evaluation and improvement.

We used the Ontario Drug Benefit Program database, which contains prescription claim records for all residents aged 65 years or older, to identify medication use. Publicly funded prescriptions are subject to a small, means-tested co-payment, which does not affect the rate at which they are obtained [Citation16]. The Canadian Institute for Health Information Discharge Abstract Database (CIHI-DAD), the CIHI National Ambulatory Care Reporting System (CIHI-NACRS) and the Ontario Health Insurance Plan Claims Database (OHIP) were used to identify patient comorbidities and health service utilization. Blood eosinophil counts were extracted from the Ontario Laboratories Information System (OLIS) database which contains information on laboratory test results for over 68,000 unique test types from the fields of biochemistry, hematology, immunology, microbiology and pathology [Citation17]. Demographic information was retrieved from the Ontario Registered Persons Database.

Study population

Individuals with COPD were identified as those who had at least 1) three outpatient visits for COPD in a two-year rolling window or 2) one COPD hospitalization. For individuals fulfilled the above case definition, the date of COPD diagnosis was the earliest date among the COPD outpatient visits or the COPD hospitalization admission. This COPD case definition has been shown to have a positive predictive value of 81% and a negative predictive value of 89% in adults 35 years and older, and a positive predictive value of 86% in adults aged 65 years or older compared to clinical evaluation by a physician [Citation18,Citation19]. As the Ontario Drug Benefit dataset only contains medication prescription claim records for people aged 65 or older, we could only include people aged 66 or older at the time of diagnosis with a one-year lookback period.

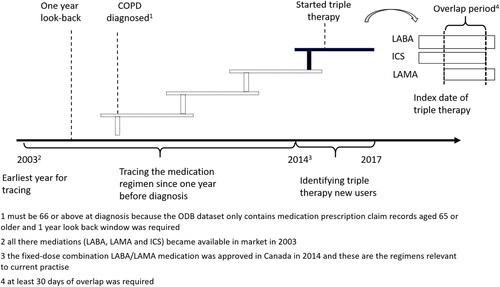

People with COPD who initiated triple therapy between January 1, 2014 and March 31, 2017 were included. Once someone was identified with COPD, they were deemed to be on triple therapy if they received LABA, LAMA, and ICS (either in free-dose or in fixed-dose combination) and their use of them overlapped for at least 30 consecutive days. Thirty days was used to avoid misclassifying patients who filled a prescription for a second COPD medication before the script ran out on their first, making it appear that their medications overlapped when, in fact, they did not. The first overlapping date of the three components was the initiation date of therapy and the index date for the study. We focused on people who started triple therapy after 2014 because the fixed-dose combination LABA/LAMA medication, which is relevant to current practise, was approved in Canada in that year. We excluded patients who received a prescription for a LABA, LAMA and/or ICS use prior to their diagnosis of COPD, i.e. the index date was earlier than the date of COPD diagnosis, because of concern the diagnosis date was not accurate or that these medications were given for a different indication. We also removed those diagnosed before January 1, 2003, as LAMAs were introduced to the Canadian market in 2003 and if LAMA were missing among those peoples’ medications it could have been because it was unavailable (). Those with a co-diagnosis of asthma on or before the index date and/or who were ineligible for drug benefits were also excluded.

Figure 1. Study design. People aged 66 and above who newly started triple theray from 2014 to 2017 were identified and their prior treatment regemins were traced unitil their COPD dianosis. However, the earlist year for tracing year was 2003 as all the three composite of triple therapy became avaiable in market in 2013.

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist; LABA, long-acting β2-agonist.

Medication regimens

We extracted medication records of long-acting maintenance pharmacotherapies (LABA, LAMA and ICS) to examine medication escalation to triple therapy starting after diagnosis. Short-acting bronchodilators were not included as they were considered rescue inhalers that were used as needed, and not as long-acting maintenance.

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics, determined on the index date, included demographic features such as age, sex, neighborhood socioeconomic status, urban/rural status, and year of triple therapy receipt; health and healthcare service utilization features such as prior comorbidities, COPD exacerbation history, primary and specialist care; performance (not results) of spirometry prior to the index date; and types of triple therapy inhaler combinations. An outpatient COPD exacerbation was identified when patients had a COPD physician visit within 7 days of receiving a respiratory antibiotic and/or short oral corticosteroid course. More severe COPD exacerbations were identified for ED visits and hospitalizations where COPD was a contributing cause [Citation20]. Baseline blood eosinophil counts was taken as the most recent value prior to the index date and was categorized using different cutoff points at 200, 300 and 400 cells/µL, if available.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics at the time of triple therapy initiation were summarized in percentage for categorical variables and as median (interquartile range) for continuous variables.

To explore how the medication regimens escalated to triple therapy over time (from this point onward referred to as escalation pathways), six intermediate regimes: LABA, LAMA, ICS, LAMA + LABA, ICS + LABA and LAMA + ICS were considered prior to initiation of triple therapy.

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was used to examine the median times from COPD diagnosis to triple therapy initiation through various escalation pathways.

We stratified the escalation pathways by people’s COPD exacerbation histories, baseline blood eosinophil counts and years of triple therapy dispensing to examine the impact of these factors on triple therapy prescription. For this analysis, we focused on the four most common and clinically relevant pathways and then grouped all the other pathways together [Citation11,Citation12,Citation21,Citation22]. The four were: triple therapy as initial treatment, LAMA to triple therapy, ICS + LABA to triple therapy regardless of prior treatment, and LAMA + LABA to triple therapy regardless of prior treatment. COPD exacerbation history was determined in the year prior to triple therapy initiation. The index years examined were 2014, 2015 and 2016/7 (As there were only three months of data available in 2017, it was combined with 2016). Blood eosinophil counts were dichotomized by different cutoff points. Pearson’s chi-squared test was used to assess for associations between escalation pathways and each of the different factors. Post-Hoc pairwise comparison tests were conducted among multiple categories of the factors using Bonferroni adjustment. All analyses were performed using R version 3.0.2.

Results

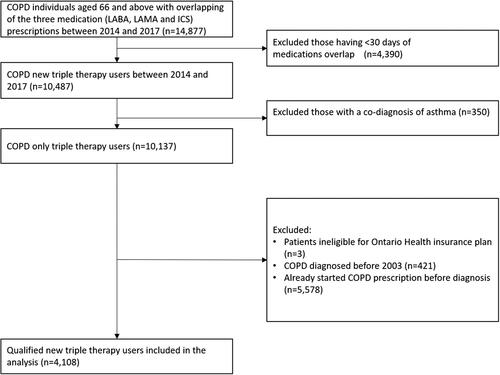

We identified 10,487 COPD patients who initiated triple therapy between 2014 and 2017. After excluding ineligible individuals, 4,108 new users were studied (). The median age of the patients was 77.1 (Interquartile range: 71.8–83.2) with 58.0% being male and 82.9% having COPD for 5 years or less. () About 88.3% had various other chronic conditions including heart diseases, hypertension and diabetes; 15.3% were receiving long term oxygen therapy and 57.7% had spirometry testing within the previous five years. Only 41.2% had had COPD exacerbations in the year before triple therapy initiation with 28.4% having least 2 exacerbations and/or 1 hospitalization. 67.3% of the patients had blood eosinophil counts available and 21.0% had a blood eosinophil counts ≥300 cells/µL. Most patient used triple therapy (96.1%) from two inhalers. The most common regimen was a fixed-dose combination ICS/LABA and a LAMA (89.2%), followed by a fixed-dose combination ICS/LABA medication and a fixed-dose combination LAMA/LABA medication (4.9%). Two percent of patients used a fixed-dose combination LAMA/LABA medication and an ICS. Three inhalers of ICS, LABA and LAMA (1.0% of people), three inhalers of ICS/LABA, LAMA and a LABA (0.9%) and some other combinations were also used.

Figure 2. Flow chart of study population selection. People were deemed to be on triple therapy if supply of the three components (LABA, LAMA, and ICS, either in free-dose or in fixed-dose combination) overlapped for at least 30 consecutive days. We excluded patients with a co-diagnosis of asthma on or before the index date and/or who were ineligible for drug benefits. We also removed those diagnosed before January 1, 2003, as LAMAs were introduced to the Canadian market in 2003 and if LAMA were missing among those peoples’ medications it could have been because it was unavailable. Those who received a prescription for a LABA, LAMA and/or ICS use prior to diagnosis were also excluded because of concern the diagnosis date was not accurate.

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist; LABA, long-acting β2-agonist.

Table 1. Selected baseline characteristics of COPD patients who initiated triple therapy in Ontario, Canada between 2014 and 2017 who had full treatment pathway available since diagnosis in or after 2003.

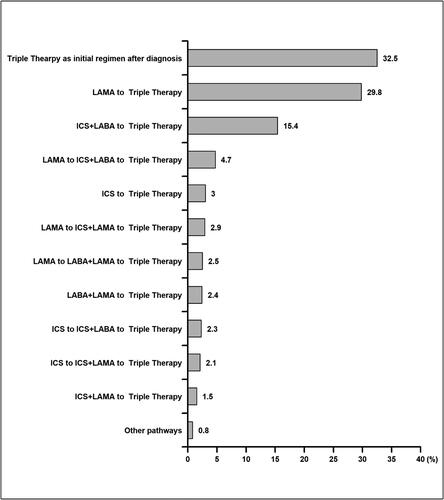

shows the distribution of observed escalation pathways from after disease diagnosis to triple therapy. The three most common pathways were: triple therapy as initial treatment (32.5%), LAMA to triple therapy (29.8%), and ICS + LABA to triple therapy (15.4%). ICS monotherapy and ICS + LAMA therapy use prior to triple therapy in 4.7% and 6.5% of COPD patients, respectively. About 927 (22%) and 224 (5.5%) of individuals progressed to triple through the intermediate step of being on an ICS + LABA or a LAMA + LABA, respectively. In both situations, they were on inhaled medications prior to this step.

Figure 3. Distribution of medication pathways progress preceding initiation of triple therapy (ICS + LAMA + LABA) among COPD patients. We only extracted medication records of long-acting maintenance pharmacotherapies (LABA, LAMA and ICS) to examine medication escalation to triple therapy starting after diagnosis. Short-acting bronchodilators were not included as they were considered rescue inhalers that were used as needed, and not as long-acting maintenance.

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist; LABA, long-acting β2-agonist.

Overall median time from COPD diagnosis to triple therapy was 362 days (95% confidence interval [CI]:331–393 days). Patients with triple therapy as their initial treatment started it about 14 days after diagnosis (95% CI: 12–17 days). Median times from diagnosis to triple therapy of the second (LAMA to triple therapy) and third (ICS + LABA to triple therapy) most common pathways were 457 days (95% CI 415–526) and 671 (95% CI 586–748) days, respectively.

describes the distribution of exacerbation history, index year and level of blood eosinophils among triple therapy new users from five pathway groups. In general, the distributions of these three factors varied between pathway groups (all three p < 0.001). The pairwise comparison showed that there was a lower proportion of individuals having ≥2 prior exacerbations and/or 1 hospitalization in the group received triple therapy as initial treatment compared to the group that escalated to triple therapy from LAMA monotherapy or ICS + LABA. A higher proportion of people received triple therapy from LAMA + LABA in 2016 and later than other pathway groups. And more people with eosinophil counts 300 cells/µL or higher escalated to triple therapy from LAMA monotherapy or LAMA + LABA.

Table 2. Medication progression pathways from diagnosis to triple therapy stratified by exacerbation history, index year and blood eosinophil count.

Discussion

In this large population study, we investigated escalation pathways from COPD diagnosis to initiation of triple therapy in older patients in Ontario, Canada. We found the three most common were triple therapy as initial treatment, LAMA to triple therapy, and ICS + LABA to triple therapy; that fifty percent of triple therapy users initiated triple therapy within one year of COPD diagnosis; and that most people who started triple therapy did not have an exacerbation in the previous year. While medication recommendations have changed slightly since the time of this study, these findings are still relevant today and can be used to inform strategies to improve COPD medication prescribing.

Our findings are consistent with previous studies showing prescription of triple therapy did not fully comply with COPD strategy documents. A US study using claims from the IMS PharMetrics Plus database from 2009 to 2013 classified triple therapy users according to GOLD criteria and found that 75.3% of triple therapy users had only mild to moderate disease [Citation8]. A UK study studying patients in the Optimum Patient Care Research Database (387 primary-care practices across the UK) from 2002 to 2010 showed that 54% of new triple therapy users belong to GOLD group A to C [Citation7]. As our study did not have access to individual patients’ symptom or lung function, we could not fully evaluate the appropriateness of triple therapy prescribed patterns by severity of disease. However, we found that 58.8% of triple therapy users did not have any exacerbations in the year prior to its initiation–a percentage similar to that reported by the above two studies.

Real-life COPD pharmacological management is affected by many factors, such as the availability of new medications, updates in guideline-based recommendations, and patient and physicians’ preferences, hence it may be difficult to compare the distribution of escalation pathways among studies from different settings and time periods. Nonetheless, we observed similar trends as other studies. Brusselle et al [Citation7] reported that the most frequent pathway to triple therapy was ICS + LABA to triple therapy in the UK. An Italian study [Citation21] found that the majority of people using triple therapy used it either as initial treatment or following initial treatment with ICS + LABA. Monteagudo et al. found around 30% of patients started triple therapy without previous inhaled therapy [Citation23]. Other studies have looked at medication escalation from one long-acting bronchodilator to triple therapy, part of the pathways we examined, and concluded that patients escalated to triple therapy mainly from LABA + ICS and LAMA [Citation10,Citation15,Citation24].

It is understandable that a substantial number of people escalated to triple therapy directly from LAMA or from ICS + LABA. In previous COPD population-based studies, LAMA monotherapy and ICS + LABA were found to be the two most commonly used treatment therapies–and a step up to triple therapy is easily achieved by adding an ICS/LABA or a LAMA, respectively [Citation25]. Our study found that that 89.2% of triple therapy users used two inhalers with a fixed-dose combination ICS/LABA mediation and a LAMA. We only observed 5.4% of individuals who escalated to triple therapy from LAMA + LABA dual therapy. This again likely reflects the prior use of medications in the COPD population. A population-based study from British Columbia, Canada, showed only 1.4% of COPD patients were receiving LAMA + LABA in 2015, while 35.4% were receiving ICS + LABA [Citation26]. As this study only included people taking triple therapy, we were unable to compare the proportions of people using LAMA + LABA and other treatments who progressed to triple therapy.

While use of triple therapy as initial treatment might be expected for people with severe disease, our analysis revealed it was used more often in patients without COPD exacerbations in the previous year. It is possible that severe symptoms prompted triple therapy to be used initially for these patients. This, however, would not be consistent with COPD strategy documents. Further studies are needed to investigate factors that trigger the prescribing of triple therapy without any preceding treatment.

This study observed some improvements in the alignment of real-world triple therapy use and COPD clinical practise guidelines. Higher rates of progression from LAMA + LABA occurred in later years of our study, while higher proportions of people escalated to triple therapy from LAMA or LAMA + LABA in the higher eosinophil counts group [Citation4,Citation6,Citation27].

The overall median time to triple therapy was 362 days indicating a substantial proportion of people started it within one year of diagnosis. While this estimation was similar to a US study which reported that 60% of patients progressed to triple therapy within 1 year [Citation22], it differed from a UK study that reported only 25% were prescribed triple therapy within one year [Citation7]. We believe that the median time was heavily affected by patients who used triple therapy as initial treatment as both our study and the US study reported substantial percentages of people who did this. The comparison of time to triple therapy for various pathways among studies likely varied because of different study settings, sample sizes and the lengths of follow-up period [Citation11,Citation22].

We used large, longitudinal, population-based healthcare administrative datasets to explore progression of medication regimens leading up to triple therapy in COPD patients. This type of data are notable for its completeness, accuracy and lack of information bias. Some limitations, however, should also be considered. First, as we mentioned above, patients’ clinical information related to disease symptoms and lung function status were not available, hence the appropriateness of triple therapy prescription could not be evaluated. Second, we were only able to study progression in patients who were diagnosed with COPD after age 66. It is not certain that this applies to people of younger ages. Third, our case definition of COPD was not perfect, and it is possible that some people in our study did not truly have COPD. Nonetheless, even if they were being mistreated for COPD, adherence to recommendations would still be expected [Citation28]. Fourth, COPD strategy documents have changed a little since the time of this study, however, not so much that the observed trends do not offer insight into how real-world physicians are likely prescribing COPD medications today. Lastly, all of the medications studied were available to patients from public health insurance for the duration of the study, thus our results might not be generalizable to jurisdictions who do not provide this access. Triple combination inhalers were also not available during study period.

In summary, real-life prescription of triple therapy often does fully follow COPD strategy documents, not only in terms of who should receive triple therapy, but also in terms of the progression of medication regimens that lead up to triple therapy. Patients’ current COPD medications should be considered when deciding to whether or not to initiate triple therapy. Education and strategies that account for this will help align medication escalation with COPD Clinical practise guidelines, and subsequently ensure best results for patients.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by ICES (formerly the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences), which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Parts of this material are based on data and information compiled and provided by the Canadian Institute for Health Information. Parts of this material are based on data and information compiled and provided by Ontario Ministry of Health (MOH). The analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed herein are solely those of the authors and do not reflect those of the funding or data sources; no endorsement is intended or should be inferred. We thank IQVIA Solutions Canada Inc. for use of their Drug Information File.

Disclosure statement

Andrea S. Gershon has received grants from Canadian Institutes of Health Research Foundation Grant during the conduct of the study; Tetyana Kendzerska has received grants from The PSI foundation outside the submitted work; Shawn D. Aaron has received personal fees from Glaxo Smith Kline and Sanofi outside the submitted work; Wan Tan has received grants from Canadian Institute of Heath Research (CIHR/Rx&D Collaborative Research Program Operating Grants- 93326) with industry partners AstraZeneca Canada Ltd., Boehringer-Ingelheim Canada Ltd, GlaxoSmithKline Canada Ltd, Merck, Novartis Pharma Canada Inc., Nycomed Canada Inc., Pfizer Canada Ltd, she has also received personal fees from GlaxoSmith Kline and Astrazeneca outside the submitted work; all other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding

This project was funded by Canadian Institutes of Health Research Foundation Grant (Reference Number: 154319). It was also supported by the Canadian Respiratory Research Network. The Canadian Respiratory Research Network is supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR)-Institute of Circulatory and Respiratory Health; Canadian Lung Association/Canadian Thoracic Society; British Columbia Lung Association; and Industry Partners Boehringer-Ingelheim Canada Ltd, AstraZeneca Canada Inc., and Novartis Canada Ltd.

Data availability statement

The dataset from this study is held securely in coded form at ICES. While legal data sharing agreements between ICES and data providers (e.g. healthcare organizations and government) prohibit ICES from making the dataset publicly available, access may be granted to those who meet pre-specified criteria for confidential access, available at www.ices.on.ca/DAS (email: [email protected]). The full dataset creation plan and underlying analytic code are available from the authors upon request, understanding that the computer programs may rely upon coding templates or macros that are unique to ICES and are therefore either inaccessible or may require modification.

References

- Soriano JB, Abajobir AA, Abate KH, et al. Global, regional, and national deaths, prevalence, disability-adjusted life years, and years lived with disability for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5(9):691–706. DOI:10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30293-X

- Barnes PJ, Burney PGJ, Silverman EK, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Nat Rev Dis Primer. 2015;1:1–21.

- Harrison EM, Kim V. Long-acting maintenance pharmacotherapy in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med X. 2019;1:100009.

- December 2019 GI for COLD. GOLD COPD 2020 strategy [Internet]. Guidelines [cited 2020 Jun 26]. Available from: https://www.guidelines.co.uk/respiratory/gold-copd-2020-strategy/455088.article.

- Nici L, Mammen MJ, Charbek E, et al. Pharmacologic management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. An official American thoracic society clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(9):e56–e69. DOI:10.1164/rccm.202003-0625ST

- Bourbeau J, Bhutani M, Hernandez P, et al. Canadian thoracic society clinical practice guideline on pharmacotherapy in patients with COPD—2019 update of evidence. Can J Respir Crit Care Sleep Med Taylor Francis. 2019;3:210–232.

- Brusselle G, Price D, Gruffydd-Jones K, et al. The inevitable drift to triple therapy in COPD: an analysis of prescribing pathways in the UK. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:2207–2217.

- Simeone JC, Luthra R, Kaila S, et al. Initiation of triple therapy maintenance treatment among patients with COPD in the US [internet]. COPD. 2016;12:73–83. Available from: https://www.dovepress.com/initiation-of-triple-therapy-maintenance-treatment-among-patients-with-peer-reviewed-article-COPD. DOI:10.2147/COPD.S122013

- Safka KA, Wald J, Wang H, et al. GOLD stage and treatment in COPD: a 500 patient point prevalence study. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis Miami Fla. 2016;4:45–55.

- Monteagudo M, Nuñez A, Solntseva I, et al. Treatment pathways before and after triple therapy in COPD: a population-based study in primary care in Spain. Arch Bronconeumol (Engl Ed). 2021;57(3):205–213. DOI:10.1016/j.arbres.2020.07.032

- Mapel D, Laliberte F, Roberts MH, et al. A retrospective study to assess clinical charactexeristics and time to initiation of open-triple therapy among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, newly established on long-acting Mono- or combination therapy. COPD. 2017;12:1825–1836. DOI:10.2147/COPD.S129007

- Hahn B, Hull M, Blauer-Peterson C, et al. Rates of escalation to triple COPD therapy among incident users of LAMA and LAMA/LABA. Respir Med. 2018;139:65–71. DOI:10.1016/j.rmed.2018.04.014

- Hurst JR, Dilleen M, Morris K, et al. Factors influencing treatment escalation from long-acting muscarinic antagonist monotherapy to triple therapy in patients with COPD: a retrospective THIN-database analysis. COPD. 2018;13:781–792. DOI:10.2147/COPD.S153655

- Bogart M, Stanford RH, Reinsch T, et al. Clinical characteristics and medication patterns in patients with COPD prior to initiation of triple therapy with ICS/LAMA/LABA: a retrospective study. Respir Med. 2018;142:73–80.

- Meeraus W, Wood R, Jakubanis R, et al. COPD treatment pathways in France: a retrospective analysis of electronic medical record data from general practitioners. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2019;14:51–63.

- Hurley J, Johnson NA. The effects of Co-payments within drug reimbursement programs. Can Public Policy Anal Polit. 1991;17(4)[University of Toronto Press, Canadian Public Policy]:473–489. DOI:10.2307/3551708

- eHealth Ontario. 2018. “Ontario laboratories information system.” [cited 2020 Jun 26]. Available from: https://www.ehealthontario.on.ca/for-healthcare-professionals/ontario-laboratories-information-system-olis.

- Gershon AS, Wang C, Guan J, et al. Identifying individuals with physcian diagnosed COPD in health administrative databases. COPD. 2009;6(5):388–394. DOI:10.1080/15412550903140865

- Gershon A, Croxford R, To T, et al. Comparison of inhaled long-acting β-agonist and anticholinergic effectiveness in older patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(9):583–592.

- Burge S, Wedzicha JA. COPD exacerbations: definitions and classifications. Eur Respir J. 2003;21(Suppl 41):46s–53s. DOI:10.1183/09031936.03.00078002

- Marco FD, Santus P, Terraneo S, et al. Characteristics of newly diagnosed COPD patients treated with triple inhaled therapy by general practitioners: a real world Italian study. Npj Prim Care Respir Med. 2017;27:1–6. Nature Publishing Group.

- Lane DC, Stemkowski S, Stanford RH, et al. Initiation of triple therapy with multiple inhalers in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an analysis of treatment patterns from a U.S. Retrospective database study. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2018;24(11):1165–1172.

- Monteagudo M, Barrecheguren M, Solntseva I, et al. Clinical characteristics and factors associated with triple therapy use in newly diagnosed patients with COPD. Npj Prim Care Respir Med. 2021;31(1):1–7. DOI:10.1038/s41533-021-00227-x

- Vetrano DL, Zucchelli A, Bianchini E, et al. Triple inhaled therapy in COPD patients: determinants of prescription in primary care. Respir Med. 2019;154:12–17.

- Wurst KE, Punekar YS, Shukla A. Treatment evolution after COPD diagnosis in the UK primary care setting. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e105296. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0105296

- Tavakoli H, Johnson KM, FitzGerald JM, et al. Trends in prescriptions and costs of inhaled medications in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a 19-year population-based study from Canada. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2019;14:2003–2013.

- Harries TH, Rowland V, Corrigan CJ, et al. Blood eosinophil count, a marker of inhaled corticosteroid effectiveness in preventing COPD exacerbations in post-hoc RCT and observational studies: systematic review and Meta-analysis. Respir Res. 2020;21(1):3.

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: The Quality Standard In Brief - Health Quality Ontario (HQO). Available from: https://www.hqontario.ca/Evidence-to-Improve-Care/Quality-Standards/View-all-Quality-Standards/Chronic-Obstructive-Pulmonary-Disease/The-Quality-Standard-In-Brief.