Abstract

The Assessment of the Burden of COPD (ABC) tool facilitates shared decision-making and goal setting to develop a personalized care plan. In a previous trial (RCT), the ABC tool was found to have a significant effect on patients’ Health-related Quality of Life (HRQoL). In this exploratory study we used data from the intervention group of the RCT to investigate if patients with health-related goals had an improved HRQoL compared to those without goals, and if the quality and types of goals differed for those who have a clinically meaningful improvement in HRQoL. We hypothesized that the quality and the type of the goal described in the ABC tool, relates to an improved HRQoL. We assessed the quality of the goals according to the Specificity, Measurability, Achievability, Relevance and Timeliness (SMART) criteria, and coded and counted each type of goal. We found that having a goal or not, did not differ significantly for those who had a clinically meaningful improved HRQoL versus those who had not, nor was the quality or type of goal significantly different. The most common types of goals were exercise more, smoke less, and improve weight. Based on the results, we speculate that when a clinically meaningful improvement in HRQoL is achieved, it is not related to a single component (i.e. goal setting as part of shared decision-making) but that the different components of the ABC tool (visualization of burden, shared decision making, utilization of tailored evidence based interventions, and regular monitoring of progress) may have a synergistic effect on disease cognition and/or behavior change. Noteworthy, the sample size was small while the calculated effect size was moderate, making it unlikely to find a significant effect.

Background

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the third-leading cause of death worldwide at this moment [Citation1]. COPD is a progressive and chronic respiratory condition characterized by airflow limitation and persistent respiratory symptoms. In COPD, self-management plays a crucial role which includes the skills needed to carry out disease-specific medical treatments, like inhaled medication which requires device handling and preparation, change health behavior and improve day-to-day control of the disease, resulting in improved well-being [Citation2,Citation3]. To change health behavior and make healthy lifestyle choices, short-term treatment goals with tangible results and decision making in collaboration with a healthcare professional are considered most effective [Citation4]. There is evidence that by achieving short-term treatment goals, lifestyle improves [Citation4,Citation5].

To support healthcare providers in providing personalized care, improve patient self-management, including goal setting, and shared decision making, the Assessment of the Burden of COPD (ABC) tool was developed. The aim of the ABC tool is to assess the experienced burden of disease, discuss this burden, the treatment options, a personal goal, and to integrate these in a personal care plan, which is agreed upon by the patient and healthcare professional [Citation6]. Patients provide the input for this tool by rating the perceived burden of their symptoms, functional state, mental state, emotional state, and fatigue via a questionnaire. Additionally, smoking status, exacerbation history, dyspnea, body mass index, lung function and physical activity are recorded. These scores are visualized in a display with colored balloons, representing the severity of each domain, and its change over time ().

In a randomized trial by Slok et al. [Citation7] it was found that about a third of its users had a clinically meaningful improvement in their Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) after using the ABC tool for 18 months. However, it is not yet clear which mechanisms contribute to this improvement.

This study focusses on goal setting as part of the ABC tool by performing a secondary analysis from the randomized trial performed by Slok et al. [Citation7]. Our hypothesis is that the proportion of goals being of good quality (defined as SMART criteria), is higher in the group who showed a clinical meaningful improvement of HRQoL in the original RCT [Citation7]. In addition, we explore if there is a difference in the type of goals (e.g. quit smoking, lose weight) between the group who has a clinically meaningful improvement and the group who has no improvement of HRQoL. To operationalize this hypothesis and exploration, we framed the following research questions: (1) Do patients with (well-described) health-related goals, both set at the time of first intervention as well as at any other moment of intervention, have an improved HRQoL compared to those without (well-described) goals at 18 months of follow-up? (2) Does the quality of these goals differ for those who have a clinically meaningful improvement in HRQoL compared to patients without a clinically meaningful improvement? (3) What type of goals do patients set and does the type of goals differ for those patients who report a clinically meaningful improvement in HRQoL compared to those without a clinically meaningful improvement?

Methods

Type of study

This is a retrospective exploratory study. We performed a secondary analysis on data collected during a Randomized Clinical Trial (RCT) [Citation6], which examined the effectiveness of the ABC tool on Health-related Quality of Life (HRQoL) [Citation7].

Data collection and description RCT

The original study was a pragmatic RCT performed in Dutch healthcare organizations [Citation6]. 357 COPD patients from 39 primary care centers and 17 hospitals participated. Primary care centers and hospitals were randomized to the intervention group or to the control group. As only the intervention group used the ABC tool, data analysis of the current study was restricted to this group (n = 173). The primary outcome was HRQoL, measured with the Saint Georges Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ). The SGRQ is a disease-specific measure of health status consisting of 50 items, with scores ranging from 0 (best) to 100 (worst). The SGRQ was administered every 6 months between baseline and the end of trial, after 18 months. A four-point improvement on the SGRQ score between baseline and 18 months later was considered clinically meaningful [Citation8].

Intervention

Healthcare providers were instructed to use the Assessment of Burden of COPD (ABC) tool during consultation. The ABC tool assesses different components of the health status of patients with COPD and gives the caregiver and patient an integrated picture of it. This visualization is aimed to facilitate a discussion between patient and healthcare provider about experienced burden, the possible treatment options, and a personal goal. This discussion should lead to the formulation of a personalized care plan, including this goal. Instructions were given that the goal should be expressed by the patient in his or her own words, in agreement with the health care professional (HCP), tailored to the abilities of patients. Patients discussed their goals during regular general practitioner (GP) visits. These visits were not predefined by protocol but scheduled in accordance with patients’ regular care. Consequently, patients could set goals during each intervention, once or multiple times during the trial. Setting goals was part of the intervention and the site staff was encouraged to do so but this was not enforced or monitored during the trial. In the study by Slok et al. [Citation6], evidence was found that the proportion of participants who showed a clinically relevant improvement on the SGRQ after 18 months was significantly higher for the ones who used the ABC tool, (49 patients (33.6%)), than the ones who did not use the tool (33 patients (22.3%)). The adjusted odds of a clinically relevant improvement after 18 months was 1.85 times as high (95% CI 1.08–3.16, p = 0.02) in the intervention group as in the control group.

Analysis

Assessment of the quality of goals

Currently, there is no generally accepted valid method to assess the quality of health-related goals but there is considerable overlap between SMART methodology and the content of good health-related goals as described by Bodenheimer and Handley [Citation4]. Therefore, we assessed the quality of goals by the SMART acronym that stands for: Specificity, Measurability, Achievability, Relevance and Timeliness [Citation9]. A goal was considered specific, if it is clearly specified what has to happen (e.g. to stop smoking). Measurability was determined if the goals could be quantified (e.g. the goal is to stop smoking completely). A goal was achievable when the HCP and patient agreed that that goal is relevant and possible to achieve. Since the trial instructed healthcare providers to describe only goals that patients agreed to, but no data were collected to monitor compliance with these instructions, we had to assume that all described goals were achievable. A goal was considered relevant when it could be related to an attribute relevant for COPD care (e.g. a goal was set to stop smoking would be relevant while a goal set to improve financial status, would not), and goals should contain a time specification for when the goal was expected to be met (e.g. stop smoking in the next 3 months).

All recorded goals during the RCT were checked for the five SMART criteria. If a criterion was met it was scored a “1,” if it was not met it was scored a “0.” As we assumed that all goals are achievable, each goal could score between one (none of the other SMART elements than Achievable were properly described) and five (all elements are properly described). We considered a goal of enough quality when it was scored four points or higher. An example of a well-described goal is: “My goal is to reduce my weight with at least 3 kilograms within the next 3 months.” An example of a poorly described goal is: “My goal is to listen well to my body.” In case multiple goals were described in the same care plan, the best goal (highest score based on the SMART criteria) was used.

Scoring was done independently by two researchers (MV and AS) who were blinded for other trial information of these patients, including who had a clinically meaningful chance in HRQoL. In case of discrepancies in coding, reviewers aligned after consultation amongst themselves.

Type of goals

Goals were coded based on their content and summed per type. They were categorized as goals related to smoking, physical activity, weight, emotion and psychological problem, exacerbation, physical complaints and symptoms, fatigue, daily functioning, lung function, dyspnea, stabilization of the current health status and medication use. The category of the goal was coded by one researcher (MV).

Statistical analysis

First, patients were grouped in (1) at least one goal vs (0) no goals, and for patients who had a goal, the type of goal was coded. Second, patients were grouped in group 1: at least one well-described goal vs group 0: only poorly described goals, set during the first intervention (i.e. intervention takes place during consultation) as well as during any moment of intervention. Independent-samples t-tests were performed to determine differences between the groups on the SGRQ change score (T18–T0). As sensitivity analysis, the Pearson correlation between the average score of the quality of goals and the change of SGRQ score between T0 and T18 was calculated. Third, the chi-square tests were performed to determine whether the proportion of patients with a well-described goal and type of goals at first intervention were equal between the group who had a minimal clinically relevant improvement of their perceived quality of life of at least four points on the SGRQ [Citation8] (MCID-group), and those who did not (nMCID group). One-way ANOVA was used to assess the association between type of goals and SGRQ. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (version 28.0, IBM. Corp., Armonk, NY). Two-sided p value ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Of the 173 patients in the intervention arm, a total of 135 patients had completed the SGRQ after 18 months of which 39 (29%) had a clinically relevant improvement of their quality of life.

Of these 135 patients, 115 patients had at least one goal described. As the protocol allowed patients to have several moments of intervention during the trial, patients could have additional goals at the time of these interventions. 98, 76, 54 and 11 patients had respectively two, three, four or five interventions where at each intervening moment, a goal was described.

Eight patients had more than one goal described at a single moment in time at any point during the trial; the best described goal was considered for analysis.

Patients with at least one goal described improved their HRQoL by reporting a decreased mean SGRQ score of 0.6 points (SD = 9.4), while the HRQoL for the patients who did not have a goal described worsened, as the reported mean SGRQ score increased with 1.8 points (SD = 12.5). However, this difference was not statistically significant (t138 = 1.081, p = 0.28, mean difference = 2.4, 95% CI [−2.0, 6.8]).

Quality of health-related goals

No significant differences in mean HRQoL scores were found for patients who had a well-described goal at the first intervention (N = 54) versus who had not (N = 61) (t113 = 0.354, p = 0.72; mean difference = 0.6, 95% CI [−2.9, 4.1]), or for patients who had a well-defined goal at any moment of intervention during the trial (N = 96) versus who had not (N = 29) (t123 = 0.098, p = 0.92; mean difference = 0.2, 95% CI [−3.8, 4.2]). Out of the 115 patients who had at least one goal described at the time of the first intervention, 34 (29.6%) had a MCID improvement on HRQoL, while 81 (70.4%) did not. Of the 20 patients who did not have a single goal described, five (25%) had a MCID improvement on HRQoL while 15 (75%) did not. At the first intervention, the proportion of well-described goals was not significantly different (X12 = 1.56, p = 0.69), i.e. 44.1% for the MCID group (N = 15) versus 48.1% for the nMCID group (N = 39). At the subsequent intervention moments, the differences between the MCID and nMCID groups were not significant either, see Appendix A. The sensitivity analysis showed similar results, i.e. no significant correlation was found between the average score of the quality of all goals set during the trial and the change of score on the SGRQ after 18 months (r = −0.046, p = 0.61).

Type of goals

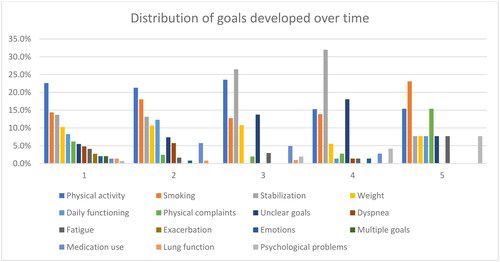

Most patients set goals related to lifestyle (i.e. exercise more, smoke less, improve their weight) or consolidate their current health status during the trial without setting a new goal, see . There was no significant difference (X12 = 11.623, p = 0.48) between the types of goals set between the patients who did (N = 39) and the patients who did not have a clinically meaningful improvement of their HRQoL (N = 94, see supplemental Table 1). We did not find a significant difference between the types of goal set during the first intervention and the change in HRQoL after 18 months (F2, 132 = 1.058, p = 0.40, details provided in supplemental Table 2).

Discussion

In this study we analyzed the goals described in the ABC tool in relationship to improvement of HRQoL. By comparing the group of patients with and without a clinically meaningful improved HRQoL, we found no differences if patients had a healthcare goal or not, quality of these goals or type of goals.

There is some evidence suggesting that by improving patient-clinician communication, including setting goals, HRQoL could improve directly [Citation10]. However, there is stronger evidence that this will occur through intermediate facilitators [Citation10]. These intermediate facilitators (cognitive-affective outcomes and behavioral outcomes) are affected first, before HRQoL will change. Merely setting goals is less likely to change HRQoL, if the underlying thoughts and feelings, or behavior itself, is not changed. Behavioral change theories emphasize that a change in behavior is more likely to occur when several factors interact with one another (goal setting, providing feedback by clinicians, and goal and patient characteristics) but less when only a single factor is affected [Citation4,Citation11]. In addition, it is to be expected that actually achieving a goal is more impactful than merely setting goals. However, the collected data did not include parameters to assess goal attainment.

Most of the set goals were considered the typical goals in COPD care. Less typical goals were rarely set, particularly goals related to emotions, fatigue and mental status. It is possible that patients and healthcare professionals are less willing or able to discuss and set goals for mental health during regular consultation. A study by van Dijk and colleagues [Citation12] amongst patients with diabetes mellitus type 2 found that patients simply do not expect primary care nurses to address psychosocial problems. This is also in line with Hessler and colleagues [Citation13] who found that there is little agreement between patient and healthcare professional on prioritizing goals to improve health-related distress, in contrast to physical goals.

One of the strengths of our study is the use of the SMART acronym for assessing quality of goals. This novel and pragmatic method allowed us to assess each goal systematically and consistently. However, by assessing goals using a method that is not yet validated, there is a risk for observer bias. To reduce this possible bias, both researchers were blinded during coding regarding which patients had a clinically meaningful improvement (MCID or nMCID group). Another limitation is that we could only assess the described content of the goals but other phenomena occurring during the consultation were not recorded, and therefore not possible to assess. For instance, verbal and non-verbal cues, and motivational aspects were not captured. Lastly, based on the limited group sizes (N = 34 in MCID group and N = 81 in nMCID group), only medium to large effect sizes (standardized effect size, Cohen’s d of 0.58 or larger) could be detected with 80% power, assuming a two-sided significance level of 0.05 using an independent-samples t-test [Citation14]. Therefore, the relatively small sample size in this study made it unlikely to find a significant effect.

Future studies should concentrate on how cognitive-affective outcomes and behavioral outcomes are affected by both goal setting and patient-clinician communication through the ABC tool, and how these factors interact with each other to affect HRQoL. This should include assessments of self-management abilities of patients, self-management support by healthcare professionals, and the quality of received care, for instance, assessed with the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC) [Citation15]. Finally, further research on the validity of the method is recommended to assess the quality of the health-related goals.

Findings from this research indicate that goals to improving fatigue and mental health, rarely were set. We would encourage healthcare providers to consider setting goals on these elements of the burden of COPD and familiarize themselves with possible options or referrals. For instance, refer to a psychologist or practice nurse specialized in mental health when patients report signs of depression [Citation16].

Conclusion

In this study, we sought to link the goal setting component of the ABC tool to behavior change. However, we could not find differences in having a goal or not, quality, or type of goals between the patients who did have a clinically meaningful improved HRQoL and the ones who did not. Behavioral change depends on a constellation of interacting factors combined with goal setting, including motivational interviewing and frequency of contact moments. It is likely that not a single component of the ABC tool is responsible for improving quality of life, but that the different components of the ABC tool (visualization of burden, shared decision-making, utilization of tailored evidence-based interventions, regular monitoring of progress) may have a synergistic effect greater than the sum of each specific part.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (552.2 KB)Supplemental Material

Download PDF (16.6 KB)Disclosure statement

MV is an employee of Boehringer Ingelheim GmbH. The other authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- World Health Organization COPD. [accessed 2023 Mar 28]. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-(copd.)

- Bourbeau J, van der Palen J. Promoting effective self-management programmes to improve COPD. Eur Respir J. 2009;33(3):461–463. doi:10.1183/09031936.00001309.

- Cravo A, Attar D, Freeman D, et al. The importance of self-management in the context of personalized care in COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2022;17:231–243. doi:10.2147/COPD.S343108.

- Bodenheimer T, Handley MA. Goal-setting for behavior change in primary care: an exploration and status report. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;76(2):174–180. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2009.06.001.

- Shay LA, Lafata JE. Where is the evidence? A systematic review of shared decision making and patient outcomes. Med Decis Making. 2015;35(1):114–131. doi:10.1177/0272989X14551638.

- Slok AHM, In’t Veen JCCM, Chavannes NH, et al. Development of the assessment of burden of COPD tool: an integrated tool to measure the burden of COPD. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2014;24(1):14021. doi:10.1038/npjpcrm.2014.21.

- Slok AHM, Kotz D, van Breukelen G, et al. Effectiveness of the assessment of burden of COPD (ABC) tool on health-related quality of life in patients with COPD: a cluster randomised controlled trial in primary and hospital care. BMJ Open. 2016;6(7):e011519. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011519.

- Jones P, Lareau S, Mahler DA. Measuring the effects of COPD on the patient. Respir Med. 2005;99 Suppl B(Suppl B):S11–S18. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2005.09.011.

- Grant H, Dweck CS. Clarifying achievement goals and their impact. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;85(3):541–553. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.85.3.541.

- Street RLJr, Makoul G, Arora NK, et al. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74(3):295–301. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2008.11.015.

- Cavalheri V, Straker L, Gucciardi DF, et al. Changing physical activity and sedentary behaviour in people with COPD. Respirology. 2016;21(3):419–426. doi:10.1111/resp.12680.

- Van Dijk-de Vries A, van Bokhoven MA, de Jong S, et al. Patients’ readiness to receive psychosocial care during nurse-led routine diabetes consultations in primary care: a mixed methods study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;63:58–64. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.08.018.

- Hessler DM, Fisher L, Bowyer V, et al. Self-management support for chronic disease in primary care: frequency of patient self-management problems and patient reported priorities, and alignment with ultimate behavior goal selection. BMC Fam Pract. 2019;20(1):120. doi:10.1186/s12875-019-1012-x.

- Dupont WD, Plummer WD. Power and sample size calculations for studies involving linear regression. Control Clin Trials. 1998;19(6):589–601. doi:10.1016/s0197-2456(98)00037-3.

- Wensing M, van Lieshout J, Jung HP, et al. The Patients Assessment Chronic Illness Care (PACIC) questionnaire in The Netherlands: a validation study in rural general practice. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8(1):182. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-8-182.

- Federation of Medical Specialists Palliative COPD care guideline 2020: https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/richtlijn/palliatieve_zorg_bij_copd/startpagina_-_palliatieve_zorg_bij_copd.html.

Appendix A

Figure A1. Visualization of the integrated health status of a patient with COPD. The five domains of experienced burden of COPD, as measured with the ABC scale, are represented by the last five balloons, symptoms, functional status, mental status, fatigue and emotions. In addition, dyspnea and level of physical activity are also reported by the patients while smoking status, exacerbations, body mass index (BMI) and lung function are reported by the healthcare providers. (Figure taken with permission from Slok et al. [Citation6]).

![Figure A1. Visualization of the integrated health status of a patient with COPD. The five domains of experienced burden of COPD, as measured with the ABC scale, are represented by the last five balloons, symptoms, functional status, mental status, fatigue and emotions. In addition, dyspnea and level of physical activity are also reported by the patients while smoking status, exacerbations, body mass index (BMI) and lung function are reported by the healthcare providers. (Figure taken with permission from Slok et al. [Citation6]).](/cms/asset/cf7f1957-20f3-4924-ae42-be5674fa78bd/icop_a_2289908_f0001_c.jpg)

Figure A2. Distribution of the percentage of goals set at times when an intervention was offered during a consultation.

Table A1. Proportion of well described goals for both MCID and nMCID groups at different intervention moments during the trial.