Abstract

At the end of World War II, United States Army officers located large troves of maps in Germany and Japan. These materials were shipped back to the United States and deposited with the Army Map Service (AMS). The AMS created a repository service to distribute the captured maps to libraries across the United States eventually sending them to a subset of thirty-five geographically dispersed institutions. While numerous libraries processed these materials, many did not, including the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, who made the decision to donate their maps to Stanford University for cataloging and scanning. The majority of the maps were duplicative, but twenty percent of the corpus were either new sets or missing sheets from existing sets. Analyzing these collections allows librarians and scholars to understand the scope of the mapping carried out by the Germans and Japanese prior to and during the war. It also provides a framework to decide if a library should allocate processing, cataloging, and digitization resources for such unprocessed collections.

Introduction

Academic map collections in the United States have greatly benefited from their participation in depository library programs from different arms of the federal government, most notably the Army Map Service, the Library of Congress, and the Government Printing Office. During and after World War II, the Army Map Service served as a conduit for libraries to receive maps from overseas stockpiles of German and Japanese captured maps. Duplicate maps abounded in these collections and were distributed through their depository system to libraries willing to catalog, house, and manage the content.

Housing the collections, while a challenge at first, turned out to be the least onerous of the requirements for receiving the maps. The greater challenge came in processing and integrating them into the collections with proper metadata. The integration of the maps captured from Germany proved to be easier than the Japanese maps as the language barrier was lower. The captured Japanese maps have been especially challenging with only a few libraries fully cataloging their maps by the early 2000s, most notably Clark University and the University of California, Berkeley.

Staff at Stanford University’s Branner Earth Sciences Library and Map Collections cataloged and integrated their German captured maps into the collections throughout the 1980s and 1990s. The Japanese maps were cataloged and scanned in the last decade, making it the first library in the United States to have digitized the corpus of over 9,600 maps. This project caught the eye of the map librarian at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, who contacted his counterpart at Stanford to, at first, see if Stanford had any gaps within their collections that UT might be able to fill with their captured map collections. Ultimately, UT discussed donating their entire unprocessed captured maps collections to Stanford where they would be cataloged, processed, and scanned for online use.

The start of the paper provides background on the capture of the German and Japanese maps and the history of the Army Map Service depository program. We then discuss the decision to consolidate the collections at Stanford, the history of the maps in both collections, and the process of moving a ton and a half of maps across the country. The next section details the integration of the maps into Stanford’s collection, discusses the degree of overlap between the two groups of maps, and the ongoing work of processing and scanning the corpus. Finally, we provide a framework for libraries with unprocessed collections to think about the management of this material.

Captured Maps and the Army Map Service Depository Program

German Captured Maps Collection

The German military was sophisticated in its creation and production of maps and prolific in its output prior to the start of World War II. The Kriegsvermessungswesen, a war survey division within the German military’s General Staff produced maps at a variety of scales (1:2,500 to 1:1,000,000) for numerous purposes during World War I. This output included terrestrial and aerial mapping, cartography, map printing, and military geology. Their output was truly impressive with the surveying units printing more than 500 million maps, sending 275 million maps to the front lines. Mapping responsibilities changed during the interwar period. The Kriegsvermessungswesen was immediately phased out in 1918. The Treaty of Versailles limited the size of the German army and navy and disbanded the air force. These and other restrictions forced surveying and mapping activities into the private sector. By 1929, military districts had taken responsibility for regional mapping.

In 1933, Adolf Hitler was appointed Reich Chancellor. Over the next few years surveying and mapping activities changed radically as the German government violated the Treaty of Versailles provision that prohibited the buildup of the military. In 1936, the General Staff of the army was formed with the responsibilities for mapping and surveying handled by the Ninth Division (later known as the Kriegs-Karten und Vermessungswesen). In the same year, the Heeresplankammer, the army map service, was reestablished with the mandate to increase map production with the Reichsamt für Landesaufnahme handling civil topographic mapping and establishing regional surveying departments within the Reich and beyond its borders. Maps were created by the mapping units and were also confiscated from stockpiles in occupied countries and reprinted as “special editions” (Neumann Citation2015).

During the course of World War II, the Heeresplankammer moved out of Berlin to Saalfeld, Thuringia, to escape air raids. The Seventh General Staff Division of the Luftwaffe also produced maps and they, too, were centered in Saalfeld by 1943 (Neumann Citation2015). These moves centralized the repository for map and geodetic data for the German military (Miller Citation2019).

Later in the war, as allied forces advanced to secure areas in Germany, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) set out to find German geographers who could provide information on the location of maps and other documents that the German army had amassed. Wilson notes that a large trove of maps was procured from Justus Perthes, although it is unclear if these were the captured maps distributed throughout the United States. He writes:

OSS map teams arrived at the Justus Perthes plant in Gotha while the city was still partly occupied by German forces. The plant was found in good condition; the working staff was on the premises, and the map stocks intact. Copies of all publications and maps, to the amount of nine tons, were removed, and interviews were conducted with the officials. (Wilson Citation1949, 306)

U.S. Army Major Floyd W. Hough and his unit, the HOUGHTEAM, went to Europe in 1944 on a secret mission with special passes issued by Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Forces (SHAEF) to “question European citizens about the movement of enemy troops, translate captured documents and interrogate prisoners of war” (Miller Citation2019, 67). They carried with them microfilming equipment and a list of technical universities, government institutions, libraries, and other places that might contain information of interest. They worked their way across Germany ending up in Wiesbaden in March 1945 where they received a tip from a captured officer of the Reichsamt für Landesaufnahme (RfL) that there would be materials of interest in a small town in the Thuringia area, about 140 miles to the east. After arriving in the area, they interrogated captured RfL officers, one who under pressure “blurted out a name: Saalfeld” (Miller Citation2019, 73). In Saalfeld, the HOUGHTEAM found the warehouse of the Germany Army filled with 250 tons of maps, data, and instruments.

The team culled this to 90 tons of maps, aerial photographs, high-quality geodetic survey instruments and reams of printed data, which they packed into 1,200 boxes to be shipped to the Army Map Service in Washington…It also included approximately 100,000 maps covering all of Europe, Asiatic Russia, parts of North Africa, and scattered coverage of other parts of the world. (Miller Citation2019, 74)

Within one hundred miles of Saalfeld another large trove of materials was discovered deep in a potash mine in Heringen, Germany by the Joint Intelligence Objectives Agency (JOIA), a subcommittee of the Joint Intelligence Committee of the Joint Chiefs of Staff of the United States Armed Forces. The collections housed here in early 1944 were primarily from the Wehrmacht’s Military Geology Library and the Patent Office collection. Mines were regularly being used by the Germans to hide materials as most were not in active production, were safe from bombing, and were dry. The materials were removed and sent first to Frankfurt and then to the I.G. Farben building in Offenbach for sorting. Materials were sent to New York to be sorted by U.S. Army personnel with items of cultural and literary value transferred to the Library of Congress, and geologic, hydrologic, or earth sciences materials sent to the U.S. Geological Survey. Captured Heringen maps were sent from the Army Map Service to the Library of Congress (Hadden Citation2008).

It appears that the majority of European maps that ended up with the Army Map Service were sent directly from sorting outposts in Germany. Wilson details an agreement whereby at least some of the captured German maps were distributed through a series of steps that started with the Military Intelligence Reporting Section (MIRS) of the SHAEF and then routed to the Office of Strategic Services London Map Division for distribution to interested agencies (Wilson Citation1949, 305). According to a “Flow Diagram of Captured Maps” (No. L4194)Footnote1 dated August 16, 1944, the maps were given to MIRS and then passed to three different divisions of the SHAEF: Engineering, Defenses, and Topography. They then passed through three different Document Sections before distribution to the British Army Document Section and the United States Army Document Section. The authors found no direct evidence that any of the captured maps came to the Army Map Service following this workflow, but it cannot be ruled out without further research.

Japanese Captured Maps Collection

Beginning in the Meiji period (1868–1912) in Japan, the Land Survey Department of the General Staff Headquarters was mandated to map certain territories beyond their borders, an area known as the “outer lands,” “foreign areas,” or gaihozu. This surveying and mapping work would continue throughout the first half of the twentieth century ending with the fall of the Japanese empire in 1945 (Wigen Citation2012). Numerous wars took place during this period resulting in the mapping of ceded territory. At times, the effort was secretive in nature with the mapping occurring in Korea (1905), Manchuria (1906), and China (1908). The program was widespread in scope to match the imperial ambitions of the Japanese (Collier Citation2015). The regions mapped include Korea, China, Manchuria, Alaska, Siberia, Micronesia, Taiwan, Mongolia, Micronesia, and Thailand as well as more distant lands such as India, Pakistan, and Madagascar.

Dr. Shigeru Kobayashi, a leading scholar on the gaihozu maps, studied in detail the rise of Japanese mapping between 1873 and 1945. During this period of time different Japanese Army units went about their work in many ways. They would build on the cartographic output of others by capturing maps, most notably after the fall of Nanjing, China in 1937. They sent in their own surveying units to newly acquired territories after a war. By the late 1920s they were using aerial photography with full-scale instrumental photogrammetry being deployed in 1929 in Korea and subsequently in other areas.

Military mapping carried on apace during World War II with survey units deployed along the front lines. Japanese survey units took over American mapping units in both Manila, Philippines and in Batavia (Jakarta) in the Dutch East Indies. The Japanese surrendered in August 1945 with directives from above to burn the maps before the arrival of the Allied forces. Kobayashi notes,

At the Land Survey Department, which had been evacuated from Tokyo and Nagano Prefecture, massive incineration of maps and aerial photographs was enforced. In Manchuria, the staff of the surveying units of the Kwangtung army burned many maps and air photographs before leaving their place of work. (Kobayashi Citation2012, 25)

Not everything ended up being destroyed. Maps and plates were discovered at the Geographical Survey Institute in Nagano Prefecture by Colonel DunbarFootnote2 of the United States Army on September 25, 1945.

At that time, the Americans confiscated original copies of many maps of overseas areas along with the plates for printing. The maps were sent to the Isetan building in Shinjuku, Tokyo, where the Sixty-Fourth Engineering Topographic Battalion was stationed. The plates were sent to Inage, Chiba Prefecture, where fifty copies of each map were printed. The original copies and the newly printed maps were sent to the Army Map Service (AMS) in the United States, which was established in 1942 to supply geographic intelligence. (Kobayashi Citation2012, 26)

Maps were taken from the Southern Manchurian Railroad Company, Toua Dobun Shoin, a Japanese educational institution in China, the Narashino Army School, and the Geographical Section of the General Staff Office of the Japan Imperial Army for transfer to the United States (Hisatake and Satoshi Citation2005).

Other stashes of maps survived and stayed in Japan. Professor Tatsuro Asai at Ochanomizu University working with Major Tadashi Watanabe secretly arranged for 50,000 map sheets to be transferred from the Headquarters of the Japanese Army to the Institute for the Science of Natural Resources. These maps were then distributed to a wide array of institutions, universities, and public libraries in Japan. Through other means, not fully understood, maps made their way to Tohoku University and the University of Tokyo (Hisatake and Satoshi Citation2005; Kanakubo Citation2005).

Map Distribution Through the Depository Program

As World War II began, the United States Office of Strategic Services was in dire need of accurate maps of enemy territory. In order to meet this need, the Map Division began to gather materials domestically and abroad from various sources. According to Wilson (Citation1949, 302), “In its infancy, the collection consisted of photographic and photostatic negatives of maps belonging to the Library of Congress, the Department of State, and the Army Map Service.” Over time, maps were procured from the National Archives, the Department of Agriculture, private collections, and university, college, and public libraries. These groups enthusiastically responded by sending a wide variety of materials in addition to maps, such as books, photographs, and reports. In Europe, the AMS worked with the British Directorate of Military Survey and the Geographical Section General Staff (GSGS), to procure and produce maps by dividing “the world into two spheres of mapping responsibility” (Wilson Citation1949, 303). The British would oversee the creation of all maps in locations in which the Directorate of Military Survey and allied mapping support were already working, while the Americans would take responsibility for all other world locations.

In order to examine the mass amounts of maps they had at their disposal, the OSS required the help of geographers, cartographers, librarians, and geologists. In 1942, the Map Information Section was created as part of the Geography Division under the Research and Analysis Branch of the OSS. “By February, 1942, a small staff of geographers had been assembled, naively filled with enthusiasm for the task ahead” (Wilson Citation1949, 299). Between 1942 and 1944, the United States and Britain, with the aid of other allied countries, continued to procure maps and produce new maps from the ones that were captured.

The AMS never forgot the generosity of American libraries at the outset of the war and decided to thank them by distributing the output of their work as well as the captured German and Japanese maps to those libraries willing to take them. They had to agree to the terms of deposit amongst which were the requirement to index or catalog the materials, to loan them upon request, and to inform the AMS of new purchases through an accessions list (Mingus Citation2012). The program was established as a partnership between the College Depository program and the AMS Topographic Command (TOPOCOM) (Nicoletti Citation1971, Rucker Citation1985).

In a letter dated November 15, 1945, W.D. Milne, Colonel of the Army Map Service Corps of Engineers, wrote to the members of the AMS Depository Library Program that “American units captured a rather large quantity of foreign maps.” The maps had been and presently were being shipped to the AMS for evaluation. The corpus included a large number of duplicates that would be “desirable and beneficial to distribute to civilian institutions.” Milne asked for the libraries to let him know if they were interested in the captured maps and if so, what areas. The text of the 1945 letter is reproduced in Appendix A.

In 1946, at the American Library Association Midwinter Meeting held in Chicago, a committee met to discuss the distribution of the WWII captured maps to select libraries. In a letter dated January 23, 1946 from Charles Steele, Chief, AMS Library, writes, “The Army Map Service has received a number of captured maps during World War II. Distribution of these maps will be made by this office in the latter part of 1946 or first part of 1947 to select geographically located libraries.” This distribution was not to be confused with the “original depository plan” as the captured maps would be given to a subset of libraries due to their limited quantity. During the midwinter conference of the Library Associations in Chicago a committee was appointed to deal with the logistical and technical questions sure to arise from the distribution of the maps with a heavy emphasis on how to store them safely. The text of the 1946 letter is reproduced in Appendix B.

The list of libraries receiving the maps was included in a letter dated February 27, 1950 to the depositories from C.V. Ruzek, Jr., Lt. Colonel, Corps of Engineers. He notes that “due to limited stocks, it has not been possible to distribute copies of all captured maps to each library on the attached list.” One hundred and fifty libraries received approximately 20,000 maps as part of the standard AMS depository program. The captured maps were sent to a smaller geographically dispersed group of thirty-fiveFootnote3 libraries (Nicoletti Citation1971). Over the next few years, the captured maps arrived in libraries across the United States. The text of the 1950 letter and the list of libraries that received captured maps is included in Appendix C.

University of Tennessee – WWII Captured Maps Background

In the fall of 2006, when the University of Tennessee (UT) map librarian became employed, he began preparing the map collection for relocation from the basement of James D. Hoskins Library (Hoskins Library) to the ground floor of John C. Hodges Library (Hodges Library). Since the World War II Captured Map collection had never been cataloged, the plan was to leave the collection in storage with other uncatalogued map collections until they could be evaluated. A finding aid had been created years prior for the captured maps, which later proved marginally helpful in identifying the scope of the collection.

In 2012, the entire map collection was relocated back to Hoskins Library, but to the second floor. The uncatalogued WWII captured maps remained in the basement of Hoskins Library. As time went on, other collection related projects and initiatives took precedence over the captured maps and smaller collections.

Before the discovery of the Ruzek letter mentioned above, no documentation was known as to how the captured maps came to UT. This led the UT map librarian in 2019 to contact a number of groups who might have more information including, Dr. Len Brinkman, retired Associate Professor Emeritus at the UT Geography Department, Alesha Shumar, University Archivist with the UT Special Collections Department, and the Chief Historian at the National Geospatial Intelligence Agency (NGA)Footnote4. A conversation with Dr. Brinkman, who had supervised the UT Geography Department Map Library from 1980-1989, helped piece together some background history surrounding the captured maps at UT. He recalled that the maps (in their original boxes) had been stored under the football stadium since the late 1940s to early 1950s, when the Geology and Geography Departments were joined as one department. At that time, the stadium was named Shields Watkins Stadium. In 1962, the football stadium was renamed Neyland Stadium in honor of Robert R. Neyland, notable head coach of the Tennessee Volunteers.

In the 1960s, the two departments separated. In 1980, the Geography Department removed the boxes from Neyland Stadium and brought them over to UT Alumni Memorial Gymnasium where they began housing and building the map collections. In 1989, the Geography Department donated the map collections to UT Libraries where they were housed in Hoskins Library. Communication with UT Special Collections and the NGA yielded no information or documentation as to how UT acquired the captured maps. Definitive knowledge of the provenance of the collection would not be confirmed until 2020 with the circulation of the letter by C.V. Ruzek, Jr. from 1950 listing the libraries who would receive the captured maps.

Stanford University – WWII Captured Maps Background

Stanford entered into a repository arrangement with the AMS in the early 1940s when Stanford President Ray Wilbur agreed that the university would house depository materials at the Hoover Library and the East Asia Library (EAL), both under the umbrella of the Hoover Institution. Almost immediately, the staff at the Hoover Library entered into negotiations with the university librarian, Nathan van Patten, to transfer the materials, including the captured German maps, to the general collections of Stanford University Library (SUL) housed at Green Library. The map transfer took place in 1952 with SUL being designated as the official repository soon after (Dimunation Citation1988). The East Asian materials, including the captured Japanese maps, stayed at EAL for another fifty years.

The Central Map Collection (CMC) was cataloged at a basic level with the catalog cards being held in a separate card catalog only available to patrons during limited public service hours. As late as 1988, no systematic work was being carried out to integrate the map holdings into an online catalog. On October 17, 1989, the Loma Prieta earthquake struck causing enough damage to Green Library that the old wing of the library had to be closed for renovation. The CMC was moved to the Mitchell Earth Sciences building that housed the Branner Earth Sciences Library and was merged with the earth sciences map collection. In order to support both map collections, staffing was increased with the hiring of a full-time map librarian and a half time map cataloger. No funding was allocated to do a retrospective conversion of the catalog cards into a digital format, leaving the staff and students to do this work manually. The sets were tackled first with the German captured maps added to the online catalog with no mention of their provenance.

In 1996, Provost Condoleezza Rice directed the Hoover Institution and SUL to reassign materials to SUL that were more or less commonplace in order to cut down on redundancies in collections and services. This would allow the Hoover Archives to concentrate their efforts on the specialized materials in their collections. This realignment included the East Asia Library with all staff and collections coming under the management of the University Librarian (Biennial Report Citation2002). Talks commenced between the head librarians at Branner Library and EAL to discuss the sizable map collection held in the basement of the Hoover Tower. An agreement was struck in 2001 with the maps moved to the sub-basement of the Mitchell Earth Sciences building in 2002. Included in this collection were over 9,000 captured Japanese military maps in pristine condition apparently never having been touched since they were unboxed and set on shelves over 50 years prior.

In 2008, a graduate student in the Center for East Asian Studies (CEAS), Meiyu Hsieh, arrived at Branner having heard that the East Asian map collection was housed in the sub-basement. Over many months, under the supervision of Jane Ingalls, the Assistant Map Librarian, she examined the collection with the remit to report on the scope and depth of the materials. She determined the collection mainly consisted of “Japanese military maps surveyed and produced by the Japanese Imperial Army roughly in between the 1880s and 1940s” (Meiyu Hsieh, report to author, November 5, 2009). She noted that from the stamps and handwriting on the back of some of the maps that they were originally housed in the Japanese Military Academy of Narashino. In addition to the topographic sheets were maps including information about forestry, water, natural resources, and traffic capacity.

Ms. Hsieh obtained funding from CEAS to begin work processing the collection. She contacted others who held copies of the maps including Academia Sinica in Taiwan and Tohoku University in Japan. Over the next year she created an inventory of the collection bringing the contents to the attention of Dr. Kären Wigen and other East Asian scholars at Stanford. A map workshop was held in October 2010 to view and discuss the maps in more detail specifically discussing their research potential. At the same time, Dr. I-Chun Fan at Academia Sinica contacted Ms. Hsieh requesting a visit to Stanford to view the collection with an offer to help sort the materials. The visit took place on December 9, 2010 with the outcome being an agreement that in exchange for copies of the digital scans created by SUL, Academia Sinica would send two graduate students to Branner Library for a month to identify, sort, and provide index maps for all sets in the Japanese collection. In addition, a symposium was planned for early October 2011 entitled, “Japanese Imperial Maps as Sources for East Asian History: A Symposium on the History and Future of the Gaihōzu” with a keynote address by Dr. Shigeru Kobayashi, the foremost expert on this corpus.

Word spread about Stanford’s collection with Azusa Tanaka, the Japanese Studies Librarian at the University of Washington, visiting in July 2015. Around the same time, the University of Washington entered into negotiations with Oregon State University to absorb their captured Japanese map collection. With this gift came official documentation including the letters from the Army Map Service outlining the program and asking for participation (reproduced in Appendix A and B). This clarified the process whereby the libraries had received their captured maps. Ms. Tanaka shared this documentation with Stanford, documentation that has yet to be found at UT or Stanford. The Oregon State maps, numbering approximately 3,800 sheets, arrived in early 2019 adding to the 3,200 sheets held at the University of Washington.

Over the next decade Stanford’s corpus was completely cataloged and processed primarily by the Assistant Map Librarian, Jane Ingalls, and map assistant, Shizuka Nakazaki. This was accomplished with the jump start received from the graduate students from Academia Sinica, the ability to copy catalog the records created by University of California, Berkeley, and consistent funding to hire a part-time staff member fluent in Japanese. After the maps were cataloged, they were sent to an in-house scanning lab on a regular schedule with images uploaded into the library catalog, Searchworks. Interactive index maps were created and added to Stanford’s spatial search engine, Earthworks. In the final tally, the Stanford collection consisted of 296 sets with a total of 9,605 sheets.

Partnership and Donation

The partnership between the University of Tennessee Libraries and Stanford University Libraries grew out of a need by UT to learn more about the provenance of their captured map collection. The goal of the UT Map Library was to make the collection more accessible to the public, but in reality, there was never an appropriate storage facility, a sufficient amount of time, or enough resources to catalog, scan, and display the maps online.

The UT map librarian learned that Stanford had already digitized and made available online a large collection of Japanese captured maps. In January 2019, he contacted Stanford’s map librarian to ask if they needed any Japanese maps to fill gaps in their collection. It quickly became clear that without detailed cataloging records with sheet-level information, there was no way to ascertain in advance if any of the maps were new to Stanford’s collection. The only solution was to send all of the Japanese maps to Stanford for processing. They soon came to an agreement that UT would donate all of its captured map collections to Stanford. Both librarians acknowledged that while there would certainly be duplicative content, it was the most efficient way to find out if the UT collection contained unique maps to add to the Stanford corpus.

In March 2020, the UT map librarian contacted the MAPS_L community to inform other libraries of the partnership between UT and Stanford with the goal to ascertain what other libraries held captured map collections, and if they knew the provenance of their holdings. Numerous responses were received with most stating they had no documentation as to the history of their collections. The collections varied in size with some libraries holding dozens of maps while others held considerably more. Some libraries noted that a portion, or all, of their maps came to their collections from faculty or staff participation in the Library of Congress Summer Program (as described by Paige Andrew, et al., “‘Will Work for Maps’: A History of the Library of Congress Geography and Map Division Special Map Processing Project,” elsewhere in this issue of JMGL). The GIS and map librarian at the University of California, Berkeley, provided a much-needed piece of the puzzle with the letter from C.V. Ruzek dated February 27, 1950 that listed all of the libraries who were to receive the captured maps from the AMS (reproduced in Appendix C). This list conclusively proved that the libraries at UT and Stanford received their maps through the AMS repository program.

Map Packaging and Shipping

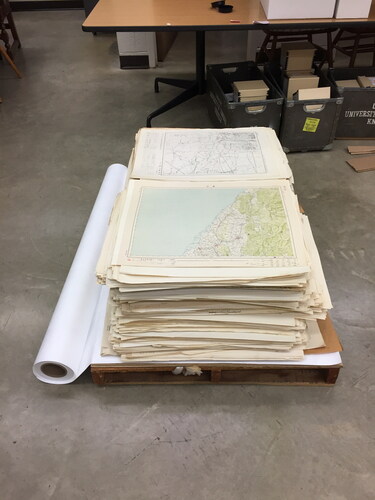

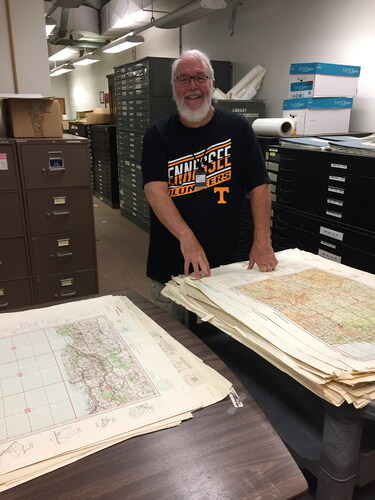

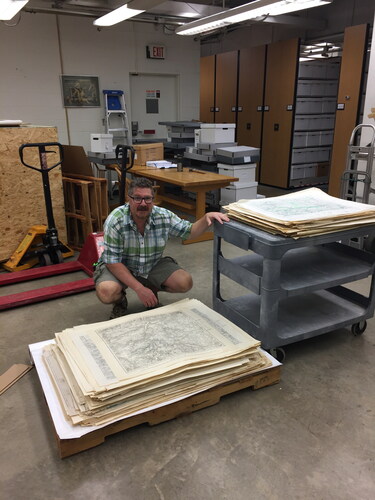

Moving the maps, weighing 1,650 pounds, out of the basement of Hoskins Library was a bit challenging. Two small elevators were the only means of transporting the maps to the ground floor which meant that the maps would have to be packed on pallets small enough to fit inside the elevators. Since the maps were being packed on pallets, they would have to be organized by size, while at the same time, trying to keep the maps in order by geographic region (see and ). Some pallets held larger maps and some with smaller maps. This was necessary to keep the maps stable and prevented the maps from sliding around. When all of the smaller pallets had been used, it was necessary to transport the maps on a cart in the elevator, then loading the maps on larger pallets on the first floor (see ).

Figure 1. Jeff French, UT Map Collection Supervisor, stands next to a stack of maps (organized by size) ready to be loaded onto a pallet in the basement of Hoskins Library. (Photo courtesy of Greg March.)

Figure 2. Greg March, UT Map Librarian, loading maps (larger maps on bottom) in the basement of Hoskins Library. (Photo courtesy of Jeff French.)

Two sheets of cardboard were placed on top of the pallet, then Tyvek sheeting was placed on top, then the maps on top of the Tyvek (see ). Staff considered using shrink wrap to secure the maps, but were concerned with moisture being trapped during transport, and so they decided to wrap the maps using Tyvek which would prevent moisture. The maps, wrapped in Tyvek, were secured with heavy staples to the wood pallet. Cardboard sheeting was then placed on top of the Tyvek and bubble wrap was used at both ends to protect the maps. The cardboard was secured with metal banding. To allow for a pallet jack to lift the pallet, the metal banding could only be used in one direction. The maps were packed on seven pallets and mailed via FedEx Freight on July 12, 2019 arriving 10 days later in California.

Integration of the Collections

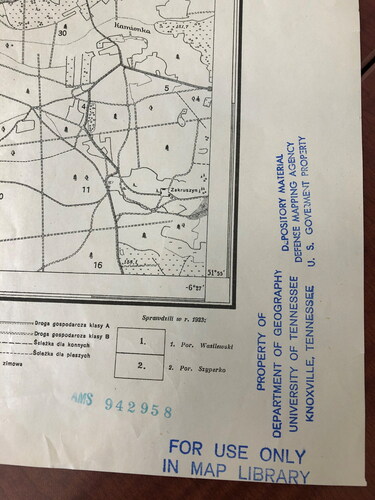

Processing of the collections began immediately upon receipt with separate workflows established for the two collections. The German collections were sorted by library specialist Tamar Ravid with the help of student workers. One hundred and forty-two sets have been completely processed, which includes 9,466 maps. Of this corpus, twenty-nine completely new sets were added to the collection and forty-three existing sets had new maps or different editions added to them. The new sets included maps from Norway, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, the Netherlands, Greenland, Morocco, and Eastern Europe with scales ranging from 1:25,000 to 1:4,000,000. Seventeen map sets remain to be processed as of December 2020, and few of the maps from the UT or Stanford collections have been scanned to date. While most of the maps were unstamped, some of the maps contain provenance information as they were stamped by the Army Map Service, the U.S. Defense Mapping Agency, and the UT Department of Geography (see ).

Figure 7. Stamps documenting the chain of ownership by the Army Map Service, the Defense Mapping Agency of the U.S. Government, and the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

Shizuka Nakazaki processed the entire Japanese collection in a little over a year. Stanford received 5,995 sheets from UT with 4,816 duplicates. Of the 1,179 new maps, twenty-three map sets totaling 239 sheets were completely new. Seventy-two map sets were supplemented with 940 sheets filling in gaps in the collections. New map sets included numerous sets of Anhui (China), other regions of China, Far East Russia, Taiwan, Sulawesi (Indonesia), Cagayan (Philippines), Europe, and India. The maps ranged in scale from highly detailed at 1,200 (Dalian, China) to 1:1,000,000 (Europe). Three donated map sets added substantially to holdings already in the collection. One hundred and eighty-eight maps were added to the Japan 1:50,000 set for a total of 973 maps with 785 duplicates identified. One hundred and eighty-four maps of Korea at 1:50,000 were added to an existing set bringing the total to 418 maps with 234 duplicates identified. Ninety-two maps of Manchuria at 1:100,000 were added to an existing set bringing the total to 390 maps with 298 duplicates identified. Each Japanese map was stamped with a unique AMS number, but none in either collection had any prior ownership stamps from Japan. This is not a surprise given that the maps were created from the captured original plates.

It is clear that the two libraries received substantially duplicative collections, but that there were meaningful differences. Both the German and Japanese collections had different sets, and that within sets, there were gaps that could be filled by a collection housed elsewhere. Similar results have been noted when comparing the Stanford and the still in-process University of Washington Japanese collections: full sets are held that do not overlap and some maps fill in gaps in each other’s collections. The next logical step is to compare the Stanford/UT holdings and the fully processed University of California, Berkeley’s German and Japanese collections.

As previously noted, when Stanford’s German maps were cataloged, the provenance of the collection was not tracked. This made it impossible to know with certainty which maps had been received through the AMS program. With the integration of the UTK maps, catalogers were able to remediate the records to add this information due to the large number of duplicate maps in both collections. The Stanford records now note that the maps have come to the library via UTK and include a Source note stating, “Maps distributed by United States Army Map Service following capture from foreign military during World War II.” A provenance note states that the German maps are part of the German World War II captured maps collection and the Japanese maps are part of the Japan World War II captured maps collection.

Looking Ahead

Captured maps remain unprocessed in many library collections across the United States. One must consider the pros and cons of accessioning these materials given the size and complexity of the corpus. By comparing the collections that have been processed, it allows the community to consider the value of accessioning more collections. Is there enough difference across the known collections to warrant the work necessary to find the unique maps in a specific collection? How many collections would have to be processed in order to safely assert that most of the unique maps received by United States libraries had been identified? Is it important to the community to know what was received in total?

Processing more of these collections is sure to yield a very high number of duplicates, probably in the range of eighty percent or more. Space is always at a premium in map libraries and knowing that the maps held in any one institution are likely to be held in another makes them candidates for deaccessioning and donation without processing as was done with the UT collection. Finding suitable homes for maps is an arduous, time-consuming, and expensive task for both the donor and the receiver.

Therefore, there are compelling reasons to process the materials at each library if resources can be found. As more collections are cataloged and scanned, the process of identifying individual maps and sets becomes easier for each subsequent library. Stanford’s collection leveraged the cataloging work done by UC Berkeley for both their German and Japanese map sets. Scanning of the same maps need not be done if high-quality scans are found at another library, leaving only new sets or maps that fill gaps in an existing collection to be digitized. Scanning allows worldwide access to collections now held primarily in paper format and has proven to be quite popular. For example, scanned maps from Stanford’s set of Japan at 1:50,000 from the captured collection are the most downloaded items from the Stanford Digital Repository.

A worthwhile endeavor would be to create a digital clearinghouse of all of the captured maps with each library submitting their unique content to a shared image catalog. Creating a shared catalog would allow for new scholarship. One would be able to ascertain what was taken out of the collections in Germany and Japan. It would allow researchers to get a more complete picture of what cartographic materials were available to the armed forces at that time. It would give one the opportunity to research when original surveying was done and when the invading forces relied on captured maps themselves to gain knowledge of a region. Such a project would be large enough in scope that grant funding would probably be needed to accomplish the goal.

Tackling these collections is a major endeavor and one that must be considered from many angles. Strong support from the faculty who are driven by interesting research questions would make funding these projects more compelling.

Conclusion

Nearly seventy years ago thirty-five libraries across the United States received tens of thousands of maps from the Army Map Service that were captured from Germany and Japan. A subset of depository libraries processed the maps in the subsequent years, but many left them unprocessed mostly likely due to the complexity of the work and understaffing. A decade-long project by Stanford to catalog, process, scan, and display their Japanese maps led to an agreement with the University of Tennessee, Knoxville to accept their captured German and Japanese maps for integration into Stanford corpus.

This melding of the collections allowed for a complete analysis of the overlap of the Japanese collections with the German statistics in the process of being compiled. Over eighty percent of maps from Japan were duplicates. The remainder either were completely new sets or filled in existing gaps in the collection. The German maps yielded the same pattern of adding new sets and missing maps to the corpus. While it was clear from the Army Map Service letters that there would be differences in what was shipped to each library, to date no such analysis had been carried out.

Other depository libraries that have not processed their collections now have a data point whereby they may think about the value of integrating their unprocessed maps into their collections given the high degree of duplication between collections. This work is time consuming and requires staff with specialized language and cataloging skills. It has been made easier by the availability of high-resolution scans and catalog records in OCLC. Processing additional collections would allow for in-depth scholarship on the collections as a whole. It would create in-depth knowledge as to what had been captured, provide an understanding of the maps available during the war, and increase knowledge as to the state of the mapped region at the time. There is also the potential to create a map portal for the captured maps possibly with grant funding. Perhaps the work has just begun.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the staff who primarily worked on this project. From the University of Tennessee, Knoxville: Jeff French helped to prepare the maps ready for shipment to Stanford University. This would not have happened without his help. Facilities staff provided the packing materials and managed the movement of the maps. The work was done by Jonathan Dennison, Steve Pursiful, Tyler Schlandt, and Terrel Whitaker. Bryan Davis and William Deleonardis worked with FedEx and helped to deliver shipping materials to Hoskins Library. Sonya Opachick and Jason Wood from the Business Office ordered packing materials and approved the FedEx shipping costs. From Stanford University: Jane Ingalls, assistant map librarian, and Shizuka Nakazaki, map assistant, worked tirelessly for years on the identification, cataloging and processing of the original collection. Andria Olson, map librarian, oversaw the processing of the University of Tennessee collection. Tamar Ravid, map assistant, managed the processing of the German maps. Shizuka Nakazaki managed the processing of the Japanese maps. The Digital Production Group scanned the maps over the last decade and continue to scan the new collections. Digital Library Systems and Services group developed and maintain the infrastructure to store and display the materials in the library catalog and in exhibit platforms.

Disclosure statement

There are no conflicts of interest to claim.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Julie Sweetkind-Singer

Julie Sweetkind-Singer is the Associate University Librarian for Science and Engineering Libraries at Stanford University. She previously spent 20 years as the head librarian with a specialization in map and geospatial librarianship at Branner Library & Map Collections at Stanford.

Gregory March

Gregory March is the Map & Government Information Librarian and Associate Professor at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. He is also the subject librarian for the departments of Anthropology, Geography, and Earth and Planetary Sciences.

Notes

1 Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the authors were unable to obtain a publication quality copy of the Flow Diagram.

2 Dr. Kobayashi states in a footnote that this “seems to be Col. Earnest A. Dunbar of the Army Map Service mentioned by Dod (Citation1966: 607-608).” (Kobayashi Citation2012)

3 Frank T. Nicoletti states that forty-three libraries received copies of the captured German and Japanese maps. He provided no source for this number and the authors have been unable to corroborate it through another source. The letter by C.V. Ruzek, Jr. (reprinted in Appendix C) lists thirty-five libraries by name that received the captured maps. The authors have chosen to use the Ruzek letter as the source for the number of libraries to whom maps were shipped.

4 The Army Map Service (AMS) was created in 1942. It was redesignated the U.S. Army Topographic Command (USATC) in 1968 and merged into the Defense Mapping Agency (DMA) in 1972. The DMA was folded into the National Imagery and Mapping Agency (NIMA) in 1996. NIMA was renamed the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) in 2003 to better reflect its focus on geospatial intelligence.

References

- Collier, P. 2015. Military mapping by Japan. In Cartography in the Twentieth Century, The History of Cartography, ed. Mark Monmonier, vol. 6, 948–51. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Dimunation, M. 1988. Review of the central map collection. Stanford, CA: Stanford University.

- Dod, K. C. 1966. The corps of engineers: The war against Japan. Washington, DC: Office of the Chief of Military History, United States Army.

- Hadden, R. 2008. The Heringen Collection of the US Geological Survey Library, Reston, Virginia. Earth Sciences History 27 (2):242–65. doi: https://doi.org/10.17704/eshi.27.2.y1vq1168q51g1542.

- Hisatake, T., and I. Satoshi. 2005. Genealogy of Japanese military maps possessed by public institutions in Japan and overseas countries. Geographical Review of Japan 78 (5):334.

- Kanakubo, T. 2005. The research committee on military geography in 1945 and Japanese military maps. Geographical Review of Japan 78 (5):334.

- Kobayashi, S. 2012. Japanese mapping of Asia-Pacific areas, 1873–1945: An overview. Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review 1 (1):137–71. doi: https://doi.org/10.1353/ach.2012.0002.

- Miller, G. 2019. “The untold story of the secret mission to seize Nazi map data.” Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/untold-story-secret-mission-seize-nazi-map-data-180973317/ (accessed May 1, 2020).

- Mingus, M. 2012. Disseminating the maps of A post-war world: A case study of the University of Florida’s participation in government depository programs. Journal of Map & Geography Libraries 8 (1):5–20. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/15420353.2011.566842.

- Neumann, J. 2015. Military mapping by Germany. In Cartography in the Twentieth Century, History of Cartography, ed. Mark Monmonier, vol. 6, 909–21. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Nicoletti, F. T. 1971. U.S. Army topographic command. Special Libraries Association Geography and Map Division Bulletin 86:2–8.

- Rucker, N. W. 1985. Defense mapping agency libraries. Science & Technology Libraries 5 (3):39–44. doi: https://doi.org/10.1300/J122v05n03_04.

- Stanford University Libraries and Academic Information Resources: 2001-2002 Biennial Report. 2003.

- Wigen, K. 2012. Japanese imperial maps as sources for East Asian history: the past and future of the Gaihōzu. Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review (E-Journal No. 2) (March). https://cross-currents.berkeley.edu/e-journal/issue-2/japanese-imperial-maps-sources-east-asian-history-past-and-future-gaihozu.

- Wilson, L. S. 1949. Lessons from the experience of the Map Information Section, OSS. Geographical Review 39 (2):298. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/211051.

Appendix A

15 November 1945

Gentlemen,

During the course of World War II, American units captured a rather large quantity of foreign maps. These maps have been and are being shipped to the Army Map Service for evaluation and necessary incorporation in the A.M.S. Library. As might be expected in a program of this nature, a fairly sizeable collection of duplicate copies exists. While this coverage is rather extensive in geographical area, it is definitely limited with regard to the number of copies of any one particular map.

The Army Map Service feels that some distribution of this material to civilian institutions is both desirable and beneficial. However, it will be necessary to make a rather restricted distribution of these maps and, consequently, the distribution will be limited to certain libraries who have already accepted our proposal to serve as a depository for Army Map Service map productions. It is very possible that institutions falling within the category outlined above may not be interested in all foreign areas and so it is requested that you furnish this office the following information:

Whether or not you are interested in receiving captured maps in addition to receipt of material for which you have already contracted.

If the answer to a. above is “yes”; is there any particular area or areas in which you consider you have a primary interest?

It would be very helpful if you gave this matter your careful attention and we would appreciate your reply as soon as possible.

FOR THE COMMANDING OFFICER:

Very truly yours,

W.D. Milne

Colonel, Corps of Engineers

Executive Officer

Army Map Service

Appendix B

23 January 1946

Gentlemen:

At the midwinter conference of the Library Association of Chicago, many questions arose regarding the Army Map Service Depository Plan. The following information is submitted for your guidance:

A good many institutions brought up the question as to why the Army Map Service was sending two copies of each map instead of one copy. It was thought advisable to send two copies so that one copy could be stored and the other copy used for reference. Then, at such a time that the reference copy was damaged or mutilated from usage, it could be replaced by the second copy. It is possible that the Army Map Service will not be able to replace a good many sheets if they are mutilated beyond use, therefore, it is advisable to receive both copies. However, if you feel that your Library desires but one copy, it is requested that this office be advised and shipments hereafter will be made accordingly.

The Library of Congress here in Washington, D.C. is preparing catalogue cards for your use. These cards will be furnished to your Library direct as each shipment of maps is forwarded by the Army Map Service. Information on these cards should reach you by 11 February 1946, quoting estimated cost, information to be shown on these cards, and all other pertinent information regarding the cards. This office is forwarding in the very near future a set of Remington Rand machine record cards for the original shipment of maps. Some of the institutions requested that machine record cards be furnished on all maps, but your decision may change upon receipt of the Library of Congress cards. Upon receipt of the Library of Congress cards a decision should be made as to which card is desired. To assist you in making a decision, the following should be kept in mind:

The machine record cards can be furnished with the holes punched into the cards or without the holes. The Remington Rand cards with the holes punched can be sorted only on a Remington Rand sorting machine. If it is desired to have the Army Map Service furnish a machine record card in place of the Library of Congress card, it is requested that this office be advised specifying whether the cards with or without code holes are desired. This office will not furnish machine record cards for any additional map shipments except those mentioned above unless requested.

Also at the midwinter conference in Chicago a committee of the A.L.A. was appointed to have technical questions channeled through. This committee will be in direct contact with the Library of Congress and the Army Map Service. The chairman of this committee is Dr. Halvorson, Johns Hopkins University Library, Baltimore 18, Maryland and Dr. Halvorson has been informed in regard to contacting manufacturers of map cabinets. Information on map cabinets should reach your Library by 11 February 1946.

The Army Map Service has received a number of captured maps during World War II. Distribution on these maps will be made by this office in the latter part of 1946 or the first part of 1947 to selected geographically located libraries. This is not to be confused with the original depository plan and these captured maps will only be furnished to the above mentioned selected groups for the following reasons:

Only a very limited quantity of these maps are available.

All of the institutions who are receiving maps under the Army Map Service depository plan will be able to obtain those captured maps through inter-library loans. This is the reason for placing them in geographically located libraries throughout the country.

All libraries will be furnished a list giving the description of the captured maps being distributed and the name and address of the institutions that this distribution is being made too (sic).

Any new or revised maps on any of the series which have been furnished your library will be furnished periodically by this office. The Army Map Service transmittal letter will specify if the maps are revised and should replace those you are holding. Upon receipt of a revised map, either of the following actions should be taken.

Return the old edition map to this office. In no case should they be given to an individual or concern.

Retain the old edition maps in your library for historical purposes.

As soon as the approved series of maps have been distributed to all depositories, additional series will be selected and transmitted to you. Your library will not receive more than three thousand (3000) maps in duplicate prior to 1 July 1946. Thereafter, approximately two-hundred and fifty (250) to four hundred and fifty (450) maps in duplicate will be furnished each month.

Numerous requests have been received in the past for certain specific maps that have not been distributed by this office as yet. Upon furnishing of these maps which were specifically requested, an invoice is forwarded by this office for requiring payment. This is to inform you that any requests received for certain maps to be furnished by this office will be invoiced at such time that maps are shipped. The maps being furnished under our Depository Plan are being transmitted free of charge. It is suggested that if you do not desire to pay for maps as explained above, wait until you receive them under the AMS plan. Most of the maps which you might request will sooner or later be furnished under this plan without cost. The Army Map Service will not furnish any of the proposed map series in advance as this would result in very much confusion at some later date.

There seems to be quite some misunderstanding regarding the availability of these maps to the general public. The maps being furnished under the Depository Plan are not to be given or loaned to the general public. The following must be kept in mind regarding this matter:

Any maps held at a university library can be used for reference anywhere on the campus but are not to be given or loaned to anyone off campus except on inter-library loan.

Maps held by a public library can be used for reference by the general public in the library but they are not to be given or loaned to them. In other words, they are not to be removed from the library except on inter-library loan.

You should be guided by the above or any other restrictions this office may make in the future. There may be certain maps on which it will not be permissible to let the public use for reference. This restriction, if any, will be furnished at the same time such shipments are made.

It must also be kept in mind that making inter-library loans between various institutions that these institutions are thoroughly familiar with the restrictions given in paragraph “c” of our letter dated 23 October 1945.

This office will appreciate receiving any questions that may arise.

FOR THE COMMANDING OFFICER:

Very truly yours,

Charles F. Steele

Chief, Library

Army Map Service

Appendix C

27 February 1950

SUBJECT: Foreign Maps

TO: All AMS Depositories

Forwarded herewith is a list of all public and university libraries in the Army Map Service Depository Program receiving captured maps as mentioned on page six (6) of the Map Depository Manual.

It should be noted that, due to limited stocks, it has not been possible to distribute copies of all captured maps to each library on the attached list.

FOR THE COMMANDING OFFICER:

C.V. Ruzek, Jr.

Lt. Colonel, Corps of Engineers

Executive Officer

Army Map Service

Army Map Service Depository List (Captured Maps)

Alabama Polytechnic Institute

Auburn, Alabama

University of Arizona Library

Tucson, Arizona

University of Arkansas General Library

Fayetteville, Arkansas

University of California Library

Berkeley, California

Claremont Colleges Library

Claremont, California

Hoover Library

Stanford University

Stanford, California

San Diego Public Library

San Diego, California

California Academy of Sciences Library

San Francisco, California

University of Colorado Libraries

Boulder, Colorado

Yale University Library

New Haven, Connecticut

Cartographic Section

National Geographic Society

Washington, D.C.

University of Georgia Libraries

Athens, Georgia

University of Hawaii Libraries

Honolulu, Hawaii

University of Hawaii

Honolulu, Hawaii

University of Chicago Map Library

Chicago, Illinois

Northwestern University Map Library

Evanston, Illinois

State University of Iowa Libraries

Iowa City, Iowa

Louisiana State University Geology Library

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Institute of Geographical Exploration

Cambridge, Massachusetts

Clark University Library

Worcester, Massachusetts

University of Michigan Library

Ann Arbor, Michigan

Carleton College

Northfield, Minnesota

Princeton University Library

Princeton, New Jersey

University of New Mexico Library

Albuquerque, New Mexico

American Geographical Society

New York, New York

New York Public Library

New York, New York

Cleveland Public Library

Cleveland, Ohio

Oberlin College

Oberlin, Ohio

University of Oklahoma

Norman, Oklahoma

Oklahoma State Library

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma

Oregon State College

Corvallis, Oregon

University of Pittsburgh Library

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

University of Puerto Rico

Rio Piedras, Puerto Rico

University of Tennessee

Knoxville, Tennessee

Southern Methodist University

Dallas, Texas

State College of Washington

Pullman Washington