ABSTRACT

Sub-Saharan Africa reports high rates of human trafficking including child soldiers, sex trafficking, forced domestic labor, and ritual enslavement. In some countries, a majority of agencies who provide anti-trafficking specific services are faith-based organizations serving local communities. The shared value of social justice expressed by both religious organizations and the social work profession presents opportunities for collaborations in this field. However, there exist many gaps in the literature on faith-based anti-trafficking interventions, including best practices, program evaluation, and strategies to improve multi-sector collaborations. This research employs a scoping review to map peer-reviewed publications on faith-based organizations in anti-trafficking in sub-Saharan Africa. We examine the types of faith-based organizations providing services in this field, identify the trafficking sectors addressed, and the interventions offered. Informed by the findings of this review, we provide a research roadmap to promote multi-sector anti-slavery collaborations with the goal of maximizing the pool of resources available to both faith-based organizations and social work researchers and practitioners. Indeed, deliberate engagement built on shared values could bolster provision of localized and responsive survivor-centered services in the region.

Modern day slavery is a globally recognized human rights and public health issue. Individuals and communities who are victimized by or at risk of human trafficking typically possess multiple vulnerabilities emerging from numerous interlocking systems of oppression (Knight & Kagotho, Citation2022; Gerassi & Nichols, Citation2018). The sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) region reports high rates of human trafficking involving child soldiers, child laborers, sex trafficking, forced labor, and ritual enslavement. The Global Slavery Index (Citation2018) estimates that there may be around 9.26 million individuals victimized by human trafficking in Africa. With the adoption of the Palermo Protocol, diverse organizations have mobilized over the past two decades to address human trafficking at local, national, and international levels (Zhang, Citation2022).

As a profession, social work with its primary mission to enhance human wellbeing and promote social justice seeks to safeguard the well-being of all at risk of or harmed by trafficking (Gerassi & Skinkis, Citation2020). Social workers have worked collaboratively with diverse actors including faith-based organizationsFootnote1 (FBOs), intervening across multiple levels including case management, clinical services, community organizing, advocacy, and research (Gerassi & Nichols, Citation2018). The shared value of social justice expressed by both religious organizations and the social work profession engenders collaborations in this field (Knight, Casassa, et al., Citation2021). Faith and religious communities are essential actors in anti-trafficking due to their political and material capital. Not only are they highly motivated and committed to social justice, which is an integral part of their respective moral codes, they possess the extraordinary resource of vast social networks that range from members in “remote villages to capital cities and the seats of power (US Department of State, Citation2020), p.24” for the sustained enactments of these moral codes (Hodge, Citation2012). In many countries, FBOs have been deeply embedded and respected for centuries as substantial providers of education, health care, and welfare (The World Bank, Citation2008).

Notably, as with other regions of the world, academic literature in SSA reports little regarding faith-based responses to human trafficking, including on faith-based partnerships with foreign or governmental aid entities. For instance, we know very little about the number and types of faith-based organizations involved in anti-trafficking, type of anti-trafficking activities, impact of these activities, demographics of clients, implementation and evaluation of FBO responses, how FBOs and their funders manage conflicts of interests, how to maximize faith-secular partnerships, and so on. The scarcity of research is both notable and alarming considering the ubiquity of faith-based human service agencies and organizations in SSA.

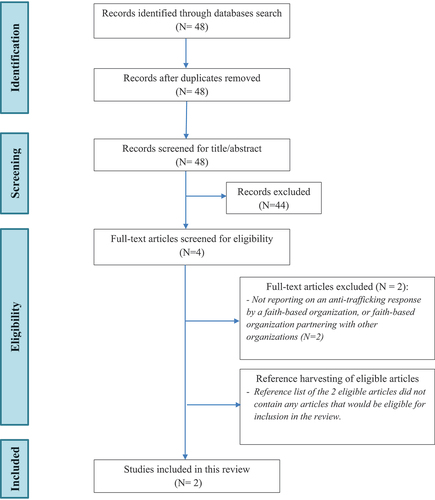

The present study reports on a scoping review of peer-reviewed literature to determine the faith-based response to human trafficking in SSA. Using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (Tricco et al., Citation2018), we identify the faith-based responses to human trafficking in SSA and the scopes of practice applied/undertaken by the FBOs involved. Examining this body of literature expands the possibility of social work engaging collaboratively with religious and faith-based practitioners.

Human trafficking in sub-Saharan Africa

Estimates by various organizations involved in anti-trafficking indicate that SSA is a region dealing with high rates of human trafficking. However, as with other localities, the precise magnitude of human trafficking within SSA is difficult to estimate due to difficulties related to measurement (Zhang & Cai, Citation2015). Communities in the region are vulnerable to exploitation due to multiple risk factors such poverty, gender bias, racism, environmental disasters, civil and political unrest, unskilled migration, and so on (e.g., Bello & Olutola, Citation2020; Woo, Citation2022). Common forms of trafficking reported include trafficking of children for adoption, child soldiering, child marriage, rituals; forced labor in domestic service, agriculture, fishing, cattle herding, camel racing, street vending, and begging; sex trafficking; organ trafficking; illegal surrogacy, and so on (e.g., Alabi, Citation2018; Lucio et al., Citation2020). Over the last couple of decades, SSA has been the recipient of significant amounts of foreign aid to address human trafficking (Gleason & Cockayne, Citation2018; Ucnikova & Ucnikova, Citation2014). Much of the reported anti-trafficking efforts in SSA in the literature rely on foreign aid and/or government funding and are executed either through an arm of local governments or local nonprofit agencies (Nwogu, Citation2014).

African religiosity

Across the region, religious and spiritual values are the foundation on which actors engage in a multitude of human needs. This is not surprising considering the importance accorded to religion and spirituality in SSA. Major communities of faith include traditional African religions, and Christianity and Islam (Panin et al., Citation2021). For instance, 82.1% of people in Kenya identify as Christians and 11.2% identify as Muslim (US Department of State, Citation2021), with faith practices having an impact on diverse domains of life, such as interpersonal interactions, bio-medical interventions, production and agriculture, and asset accumulation (e.g., Kagotho & Kagotho, Citation2022; Spaling & Vander Kooy, Citation2019). African religiosity remains significantly higher than in other global regions, with 90% of respondents to the Pew Research Center (Citation2018) in sampled SSA countries (Ethiopia, Nigeria, and Zimbabwe) indicating that religion was “very important” in their lives. In comparison, the average percentage of respondents selecting “very important” across the European and Latin American countries sampled was 23% and 60%, respectively (Pew Research Center, Citation2018). Respondents to the Afrobarometer (Citation2018) surveys indicated that religious leaders are still the most trusted authority figures in SSA. Scholars have noted that SSA’s shifting religious demographics (increasing popularity and status of Christianity and Islam) has an impact on the politics and economics of the region (e.g., Kaag & Saint Lary, Citation2011; Panin et al., Citation2021).

Faith-based responses to human trafficking

Large international bodies and humanitarian organizations, such as the United Nations and its subsidiary organizations, have been uniquely significant in the war against modern day slavery. FBOs – which are part of civilsociety – provide services through multiple avenues including as either registered and unregistered not-for-profit organizations (Woldehanna et al., Citation2005). In many countries, faith-based organizations are either the largest social service providers after the government, or the primary provider of social services (e.g., Grim & Grim, Citation2016; Rozario & Rosetti, Citation2012). International organizations, including the World Health Organization (WHO), the United Nations and its subsidiary organizations, and the World Bank, channel some of their development aid through FBOs. They are increasingly recognizing the potential of partnerships with FBOs (James, Citation2009). For instance, the World Bank since 2015 has intensified its collaboration with FBOs active in low to middle-income countries for accelerating both the scale and impact of their activities in impoverished areas (The World Bank, Citationn.d..).

Examples of faith-based responses to human trafficking can be found at the local, national, and international levels. In some countries, a great majority of agencies that provide trafficking-specific services are faith-based organizations serving local communities (Barrows, Citation2017; Bernstein, Citation2018). The Talitha Kum network, founded in Italy in 2009, is a network that connects Catholic women in over 92 countries (Talitha, Citationn.d.). They facilitate collaboration and the exchange of experiences to strengthen efforts to combat human trafficking and provide a wide range of services for victims. The nonprofit T’ruah brings together over Jewish 2000 rabbis and cantors, and their congregations, in efforts since 2011 to combat human trafficking in the agricultural industry in the USA (T’ruah, Citationn.d.). In 2013, a FatwaFootnote2 was issued by the Al Azhar Al Sharif, Preaching and Opinion Committee in Egypt, considered by many academic and political leaders as the highest authority regarding the study of the Quran, which decried modern slavery and human trafficking from a Muslim perspective based on the teachings on the Quran (Global Freedom Network, Citation2014). This Fatwa has been important in combating Boko Haram in Nigeria (Global Freedom Network, Citation2014). Notably, in 2014, the top global religious leaders of the world’s major traditional religionsFootnote3 gathered to sign the Joint Declaration of Religious Leaders Against Modern Slavery and “clarified ambiguity toward modern slavery in various religious texts, and proclaimed once and for all that modern slavery is not acceptable in the eyes of any of the great faiths, indeed, never under God” (Global Freedom Network, Citation2014, p. 4).

Examples of FBO work in SSA include Caritas Internationalis, which coordinates several Christian FBOs in a multilateral anti-trafficking project along migration routes in Malawi, Eswatini, and South Africa (Caritas Internationalis, Citationn.d.). They aim to strengthen vulnerable communities through prevention and protection strategies, for instance through micro-development projects that reduce the need to migrate and education about trafficking, in collaboration with local community and faith leaders. As another example, in Senegal, the UNODC and the government work together with religious teachers to eradicate forced child begging (US Department of State, Citation2020). In Kenya, Religious Against Human Trafficking (RAHT), a coalition of both faith communities and the laity, interacts with practitioners, law enforcement, and policy-makers to provide services to survivors and at-risk individuals and to engage in a policy environment to eradicate human trafficking in the country (RAHT Kenya, Citationn.d.).

Faith-based human service organizations offer not only material resources for addressing trafficking but also strong moral resources. They can motivate community behavior based on a deep commitment to religious values combined with a reach of around 90% of the world’s population (Global Freedom Network, Citation2014). A united effort of world religions for the teaching and application of religious values that promote justice, equality, and fraternity can be part of promoting the shift of cultural norms needed for sustained, deeply rooted, value-driven change to dismantle systemically unjust and exploitative economic, political, and social systems that perpetuate human trafficking and replace them with just and equitable ones. Additionally, the spiritual resources offered by these organizations are among the sources of recovery, strength, resilience, stability, and identity for individuals who have been trafficked or are at risk of trafficking (e.g., Hodge, Citation2021; Knight, Xin, et al., Citation2021).

Gaps in the literature

Scholars have noted that even after two decades of research initiated after the Palermo Protocol, the need for rigorous evaluation of anti-trafficking interventions and policies remains (e.g., Bossard, Citation2022; Bryant & Joudo, Citation2018). Also, absent are studies that help us understand and improve multi-sector collaborations in anti-trafficking work (e.g., Gerassi & Nichols, Citation2018; Sheldon-Sherman, Citation2012). These noted gaps in conjunction with the nascent nature of prevalence science with regard to measuring human trafficking (e.g., Zhang, Citation2022) severely impact our ability to know and do “what works” in real-world settings.

Notably, little peer-reviewed research can be found regarding the participation of faith-based organizations in anti-trafficking in light of their roles as key actors. The small body of existent peer-reviewed research seems to fall roughly into two broad categories on the polar ends of caution and favor regarding faith-based anti-trafficking work. In the first category are critiques, often developed without faith-based representation in the research process, of how faith-based organizations employ the moral, religious, or political paradigms that foster policies and activities that restrict the rights of individuals to their bodies and labor, and how their views of trafficking are often incongruent with survivors’ own viewpoints (e.g., Cojacaru, Citation2016; Zimmerman, Citation2010). The second category of studies reports FBO interventions favorably but whose rigor and methodological approaches are difficult to ascertain (e.g., Schrader & Jennifer, Citation2012). These methodological deficiencies call into question their findings on intervention success, acceptability, or mechanisms for identifying and rectifying any unintended negative impacts collaboratively with clients.

Methods

To map the state of literature on faith-based responses to human trafficking in SSA, we conducted a scoping review of peer-reviewed literature to answer the research question, “What are faith-based responses to human trafficking in sub-Sahara Africa?” Scoping reviews are used when examining how research has been conducted on a specific topic, enabling the identification and analysis of the research gaps and nature of nascent work in a new area as a foundation for further research (Munn et al., Citation2018). We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (Tricco et al., Citation2018) as a framework for the scoping review. Objectives of the review were to

Map peer-reviewed publications on faith-based anti-trafficking interventions in SSA

Identify the types of faith-based organizations involved

Identify the types of human trafficking crimes addressed

Identify the level of interventions offered

We employed a comprehensive search strategy for retrieving peer-reviewed articles on faith-based responses to human trafficking in SSA to maximize the likelihood that as many relevant articles as possible would be included in the review. Five academic databases (Academic Search Complete, Africa Wide Information, Women’s Studies International, SOCIndex with Full Text; Social Science Abstracts) were searched for articles published after 2000 (after the Palermo Protocol was ratified) using the following combinations of search words: “Africa” OR “sub-Saharan Africa” AND “faith” or “religion” AND “Anti-trafficking” or “human trafficking” or “sex trafficking” or “labor trafficking” or “slavery” or “child labor” or “child sex trafficking” or “child soldier” or “forced begging” or “organ trafficking.” Full-text screening was performed on the records from the databases with the following criteria:

Inclusion criteria

Reports on the response to human trafficking by a faith-based organization, or by a faith-based organization partnering with other organizations, published in English outlets between 2000 and 2022. “Response” and “faith-based group” are defined, respectively, as follows: (i) any micro-, mezzo-, and macro-level intervention, including religious interventions such as prayer, (ii) FBOs, i.e., any organization or group whose identity and/or mission are derived from the teachings of religious or spiritual traditions which operate as registered or unregistered, nonprofit, voluntary entities (Berger, Citation2016).

Exclusion criteria

Articles were excluded if no intervention was described, i.e., articles that discussed conceptual, legal, religious, moral, or cultural issues without an actual on-the-ground response to human trafficking. (the PRISMA chart) shows a summary of the study selection process.

Forty-eight (48) records were identified and imported into Covidence (Covidence, Citationn.d.). Both authors independently reviewed the titles and abstracts using Covidence for relevance. The reference lists of these articles were examined for further relevant articles for inclusion in the scoping review. None were found, leading to a total of two articles being included in the scoping review after database searches and reference harvesting and reviewer discussion and consensus (see ).

Table 1. Summary of Research Articles.

Results

Ander’s (Citation2018) study describes a partnership between a church, Cornerstone, and a grassroots organization, Dorah’s Ark, for the care of orphan children who were at risk of being trafficked. Communication and mutual respect between the partner organizations were described as key elements to project success that could be utilized by other churches for successful partnerships. Dorah’s Ark was unable to access government funding for their services and that the church was able to fill the resource gap with immediacy illustrates the potential of faith congregations as actors in anti-trafficking. Her practice recommendation of partnerships between local congregations and grassroots organizations aligns with research and praxis on multi-sector, interagency, collaborative, or coalition work in anti-trafficking (e.g., Jones & Lutze, Citation2016).

Plambech’s ethnographic study of Nigerian economic migrants deported from Europe due to “sex trafficking” shows how Christian FBOs working with these trafficked individuals invoke the powerful languages of God, morality, and nation-building to achieve moral governance of these individuals’ sense of citizenship. She discusses the range in degrees of alignment with these discourses among the women receiving services, and how some women also utilize traditional religions (consulting witchdoctors) as a resource for understanding their deportation. Echoing critical studies of migration policies and sex trafficking (e.g., Andrijasevic, Citation2010). Plambech’s study highlights the distance that can exist between the paradigms and purposes of anti-trafficking FBOs and their clients who have been discursively and legally positioned as “sex trafficked” by state apparatus.

Ander’s study was non-empirical; while the author described the project as successful, it was unclear how “success” was measured and whether all parties involved would share the author’s evaluation. In a similar note, Plambech (Citation2017) did not mention how the FBOs in her ethnographic study assessed program implementation or effectiveness. Both studies note that faith organizations reported on foregrounded faith values as the motivation for the church engaging in anti-trafficking and providing spiritual care as essential elements of their service.

Discussion

Anecdotally, the role of faith-based organizations in addressing modern day slavery is undeniable. Indeed, major faith traditions have in the recent past made declarations against human trafficking and other labor exploitations and committed significant resources to address this scourge (e.g., Global Freedom Network, Citation2014). This study reports on a scoping review of articles on the faith-based responses to human trafficking (HT) in SSA. Notably, as with other regions of the world, academic literature reports little regarding faith-based responses to human trafficking in SSA, including on faith-based partnerships with civil society, foreign or governmental aid entities. A comprehensive search of academic databases yielded only two articles for review, indicating a startling lack of peer-reviewed research on faith-based responses. This lack of information makes it difficult to identify promising strategies, understand FBO roles locally in advocacy, and critically analyze their activities and motivations.

Gaps in knowledge revealed in this review include (i) the types, reach, and volume of interventions engaged in by faith-based responses to HT in SSA, (ii) how their motivations are shaped by religious, cultural, and economic views and constraints, (iii) the effectiveness and sustainability of these interventions, (iv) how such responses are rooted in (or not) local sensibilities and priorities, (v) how transparent or accountable FBOs are for the local or international funding received, (vi) how collaborations with other agencies or foreign development funding streams affect the religious nature of these organizations and their service agendas and outcomes, and (vii) whether their anti-trafficking activities are reinforcing or challenging inequalities locally and internationally. In synthesizing the current knowledge and raising questions about current faith-based anti-trafficking efforts and functions, this manuscript provides a starting point for further scholarly inquiry. In this section, we propose guiding questions to bolster the present knowledge base. These questions are positioned to help the field examine what has worked and what has not within the localized milieu.

Implications for research

Who do they serve?

While there are commonalities across the industries and sectors that foster and perpetrate HT in SSA (e.g., domestic servitude, mining, agriculture, fishing, child soldiers), regional differences demand that organizations embrace localized and responsive approaches. A global mapping of the client base across regions and by industry would pinpoint gaps in practice and in particular populations that may be unreached or who are underserved in the existing framework. Further, program compatibility, i.e., the degree to which FBO services align with the expressed needs of survivors and at-risk communities, is best understood in a democratized research space where client voices and experiences are centered. Indeed, gaps in stakeholder inclusion in Ander’s and Plambech’s study highlight this key group of people whose viewpoints are too often excluded from adequate representation in human trafficking research.

How does organizational climate and culture inform service provision?

Next would be research examining the values and norms that inform these organizations’ approach to HT. In other words, what are the moral, spiritual, political, and/or financial motivations for becoming involved in anti-trafficking work and further, how do these impact the services they offer? Examining the value base provides a glimpse into organizational standpoints regarding larger discourses of good citizenship, migration, gender, safeguarding of the vulnerable, and so on that have real implications on how well services align with client needs.

Recognizing that faith-based organizations may have missional or political agendas as an integral part of their organization and activities, it would also be important to study strategies for enabling FBOs to genuinely provide aid in an inclusive, nondiscriminatory, and non-judgmental manner, and for identifying ways that they might be (unintentionally) exploiting vulnerabilities in communities that do not have alternative means of obtaining trafficking services, healthcare, education, and so on (Chima, Citation2017). Such research could help faith-based organizations with remaining true to their stated objectives of social justice and development assistance in ways resonant with communities they are serving, and to protect these communities from faith-based assistance that promotes “neo-colonialism, cultural domination, hegemony, or the recolonization of the African mind (Chima, Citation2017, p. 2).” This is particularly pertinent as faith-based organizations in SSA are typically associated with the large monotheistic religions whose centers of power are outside SSA, namely Christianity and Islam, and whose worldviews and tenets differ from traditional African religions. That these large faith organizations own significant assets and memberships being associated with social privilege and wealth accumulation in some parts of SSA also makes such research pertinent (Kaag & Saint Lary, Citation2011).

Research would also need to explore how the unique faith identities, integrity, and rights of faith-based organizations may be protected and respected. Unruh and Sider (Citation2005), for example, note the complicated place that faith-based organizations have in promoting the values and civic habits that sustain political institutions while having a moral responsibility to hold these institutions accountable to transcendent or higher standards of justice. While faith-based organizations are expected to serve the vulnerable without discriminating against religion or other aspects of identity, they should also be free to compete for funding without contradicting their own values, and to provide services in a way that is congruent with their faith values. Research is needed for a more thorough and localized understanding of the tensions that FBOs face and for strategies for managing these well (Vanderwoerd, Citation2004).

Are interventions culturally acceptable?

Furthermore, research on these fundamental questions should be undergirded by the dual praxis-oriented goals of discovering how best to maximize the potential benefits of FBO participation in anti-trafficking in SSA, while minimizing the risks involved. For instance, evaluation activities and strategies could assess the acceptability to local communities, the organizations' relationship with local communities, and the ways in which FBO involvement shapes the strategies or understandings of other sectors and partners. A priority area for research would be how faith-based organizations could institute and strengthen accountability mechanisms to monitor and improve the impact of their engagement with vulnerable communities in truly collaborative ways with these communities, and to share evidence-based faith-centered data that contributes to knowledge and practice (Boro et al., Citation2022). Groups such as The Joint Learning Initiative on Faith and Local Communities, a monitoring, evaluation, accountability, and learning hub (Joint Learning Initiative on Faith & Local Communities, Citationn.d.), may be valuable partners for such endeavors.

What is the nature of external collaboration?

Future research must also pay particular attention to the material and ideological resources employed by FBOs in collaborations or partnerships with other actors including funding partners. For FBOs who are recipients of international or government funding, research on participatory accountability mechanisms could contribute toward knowledge needed to address problems associated with receiving developmental aid, such as “creating dependency cycles, stifling of local growth, limiting the ability of organizations to fundraise locally, creating a lack of local identity or weak resonance with the people NGOs claim to help, and corruption – the rise of ‘fake’ groups established to capture some of the abundant foreign aid” (Nwogu, Citation2014, p. 57). Similarly, another issue requiring research is isomorphism or “mission creep” where FBOs receiving external funding shift the emphasis and nature of their social justice efforts to comply with grant criteria and other external pressures (Schneider, Citation2013). FBOs that are challenged by the lack of alternative funding, poor management practice, and other organizational problems may be especially vulnerable to such external pressures (Ahmed, Citation2009).

Other directions for future research include research on effective collaborations between faith-based organizations and other sectors (Lagon, Citation2015). Fully leveraging the potential of faith-based responses to HT would involve a synergy of faith-based communities which comprise around 90% of the world’s population. This means seeking to understand and improve the extremely complex activity of developing more local, national, regional, and global intrafaith, interfaith, and faith-secular partnerships to create coherent responses between all actors (Boro et al., Citation2022). Locally, in SSA, building toward such synergy would entail FBOs inculcating sensitivity toward local cultures. For instance, FBOs and partner organizations, including international aid agencies, could incorporate African traditional philosophies of Ubuntu, tolerance, brotherhood, and communality into their discourses (Metz & Gaie, Citation2010; Chima, Citation2015). Also, considering that the syncretic nature of local religious or spiritual practice, where a very large majority of Africans visit traditional healers regardless of their religious beliefs or inclination (e.g., Plambech, Citation2017; Chima, Citation2015), faith-based organizations need to consider how they might work with African belief systems and traditional medicines in ways that promote the wellbeing of the communities they are rooted in and are tolerable to their own faith values and belief systems.

Implications for social work training

Responsive social work researchers

The need for research on faith-based responses to human trafficking implies that religious and spiritual competence is necessary for academics, particularly as academics tend to have disproportionately lower levels of traditional theistic beliefs than the general population (Hodge, Citation2019). Such training is important also because spiritual worldviews tend to have little currency or political weight in academic discourse beyond being a subject of study or critique (Hodge, Citation2019); human trafficking research to date often contains a rather cautious orientation toward faith-based motivated anti-trafficking work (e.g., M. Twis & Praetorius, Citation2021). Considering that FBO anti-trafficking activities involve faith-secular partnerships and secular funding of faith organizations, researchers who train in religious or spiritual competence would also be equipped to support secular government and non-governmental organizations in producing quality reports about their work with FBOs.

Attaining competence could include training on the following topics (Hodge, Citation2002; Moffatt & Oxhandler, Citation2018): 1) empirical research on religion and spirituality, 2) theoretical explanations for individual and community strengths fostered by spirituality, 3) spiritual diversity and demographics of the population, 4) the spiritual traditions or religions in a population, 5) value conflicts and ethical dilemmas, 6) spiritually based interventions, 7) assessment and operationalization, 8) discrimination faced by spiritual or religious believers, including discrimination in academia, 9) rights of spiritual or religious individuals and groups, 10) reflexivity regarding religious or spiritual biases or ethnocentrism, and 11) challenges faced by faith-based organizations engaging in social justice and development work.

The goal of such training would be to equip social work researchers to view religious or spiritual communities’ values, norms, practices, and goals through a lens of cultural humility or responsiveness without compromising research ethics or their ability to challenge inequities that may be promoted by a faith-based group’s response to human trafficking, and to foster effective and equitable collaborations between faith-based organizations, vulnerable communities, and other actors involved in anti-trafficking. We specially note that the deeply held values of FBOs which may exclude non-adherents are in contradiction with social work practitioners and other human service professions. The social work code of ethics requires practitioners to serve all clients and ensure that our scope of practice extends beyond the immediate client to encompass the needs of the larger society. While values of client service and dignity and worth of all individuals auger well with anti-trafficking strategies, given that the disruptive effects of trafficking extend to families and communities of trafficking victims and survivors, more research is needed to determine how faith and religious values interact with FBO service provision; the degree of tangible fit between meaning and values attached to the intervention by involved individuals; how those align with individuals’ own norms, values, and perceived risks and needs; and how the intervention fits with existing workflows and systems.

Democratizing the research process

The research to propel this body of evidence forward must be undertaken in ways that involve the democratic and equitable inclusions of all stakeholders in order to reduce the likelihood that knowledge produced would reflect the privilege, biases, or agendas of some parties over others (Knight & Kagotho, Citation2022). We note that both reviewed articles did not reflect inclusive modes of inquiry. While Ander (Citation2018) describes as “successful” a model of collaborative partnership between a local South African church and community service organization, her evaluation of project “success” did not include the service recipients’ (the children) perspectives, or any systematic and participatory ways of establishing what counts as “success” for their program. Plambech’s (Citation2017) study provided a thorough description grounded in ethnographic methods of how Nigerian faith-based NGOs’ framing of women’s deportation served agendas within national and global discourses of morality and migration but did not discuss any dialog between her and the religious NGO staff regarding their different standpoints on deportation and the harms or inequities produced by the discourses invoked. Nor did she suggest that such dialogs be conducted in the future.

We would emphasize the importance of incorporating the perspectives and experiences of marginalized groups through participatory and power-sharing research methods into the intellectual grounding of the field so knowledge produced can challenge inequality, and better represent and address the needs of victims and at-risk individuals/groups (M. K. Twis & Preble, Citation2020). Similarly, while human trafficking scholars have produced numerous critical accounts of faith-based responses to human trafficking (e.g., Bernstein, Citation2018; M. Twis & Praetorius, Citation2021), much of this scholarship does not integrate emic perspectives or was not produced collaboratively with members of the faith community at hand (Knight & Kagotho, Citation2021). These accounts are deeply valuable in how they highlight areas of concern for faith-based organizations to reflect and make corrections. Apart from equitable engagement and collaborations, however, knowledge produced will be limited in its analysis of the flaws and strengths of faith-based responses. It is thus in turn limited in its ability to bridge the gap between academic and faith-based actors, and its ability to complicate trafficking discourses and produce useful knowledge for practice that integrates the experiences and insights of both parties.

Limitations

This review has several limitations. First, only studies published after the adoption of the Palermo Protocol in 2000 were reviewed. This cutoff was informed by the global legislative and programmatic impact of the Palermo Protocol as well as the significant resource investments directed to addressing human trafficking in this period. Thus, as with all scoping reviews where a time frame is stipulated, this study is not inclusive of all peer-reviewed material on faith-based HT interventions. In addition, as this scoping review aimed to identify academic literature, non-peer reviewed sources were not covered in this review. This in spite of the authors’ acknowledgment that the questions posed in our discussion section may well be addressed in organizational reports and other monitoring and evaluation documentation. Examining this body of literature is an important area for future review.

Conclusion

Modern day anti-slavery interventions have been hindered by a lack of information on the nature of services offered. The enormous influence of faith communities and their equally significant role in delivering social services suggests that they are critical development partners and agents of change for human trafficking. However, the extraordinary dearth of research on FBOs providing services to communities at risk of trafficking in SSA entails that “further” inquiry has to start at the very beginning with the most fundamental questions. Questions that examine how FBO characteristics include service delivery, organizational policy, and their interaction with the local cultural milieu are proposed.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Faith-based organizations include “places of religious worship or congregations, specialized religious institutions and registered or unregistered nonprofit institutions that have religious character or missions” (Woldehanna et al., Citation2005, p. 27).

2. A Fatwa is a ruling on a point of Islamic law given by a recognized authority (Hassan & Khairuldin, Citation2020).

3. Catholic, Anglican, Orthodox, Buddhist, Hindu, Jewish, and Muslim faiths.

References

- Afrobarometer. (2018). Afrobarometer Data, Round 7, 2016/2018. http://www.afrobarometer.org.

- Ahmed, C. (2009). Networks of Islamic NGOs in sub-Saharan Africa: Bilal Muslim mission, African Muslim agency (direct aid), and al-Haramayn. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 3(3), 426–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/17531050903273727

- Alabi, O. J. (2018). Socioeconomic dynamism and the growth of baby factories in Nigeria. SAGE Open, 8(2), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244018779115

- Ander, D. (2018). Mama Dorah: Uplifting grassroots efforts to combat human trafficking. Social Work & Christianity, 45(1), 86–93.

- Andrijasevic, R. (2010). Migration, agency and citizenship in sex trafficking, migration, minorities and citizenship. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Barrows, J. (2017). The role of faith-based organizations in the US anti-trafficking movement.Human trafficking is a public health issue. M. Chisolm-Straker & H. Stoklosa, (Eds.) Springer.

- Bello, P. O., & Olutola, A. A. (2020). The conundrum of human trafficking in Africa. In J. Reeves (Ed.), Modern slavery and human trafficking (pp. 15–27). IntechOpen.

- Berger, J. (2016). Religious organizations. In A. Farazmand (Ed.), Global encyclopedia of public administration, public policy, and governance. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31816-5_2514-1

- Bernstein, E. (2018). Brokered subjects: Sex, trafficking, and the politics of freedom. University of Chicago Press.

- Boro, E., Sapra, T., de Lavison, J. F., Dalabona, C., Ariyaratne, V., & Samsudin, A. (2022). The role and impact of faith-based organisations in the management of and response to COVID-19 in low-resource settings: Policy & practice note. Religion and Development, 1(1), 132–145. https://doi.org/10.30965/27507955-20220008

- Bossard, J. (2022). The field of human trafficking: Expanding on the present state of research. Journal of Human Trafficking, 8(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322705.2021.2019527

- Bryant, K., & Joudo, B. (2018). What works? A review of interventions to combat modern day slavery. https://www.walkfreefoundation.org/news/resource/works-review-interventions-combat-modern-day-slavery/

- Caritas Internationalis. (n.d.). Caritas Internationalis. https://www.caritas.org/

- Chima, S. C. (2015). Religion politics and ethics: Moral and ethical dilemmas facing faith-based organizations and Africa in the 21st century-implications for Nigeria in a season of anomie. Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice, 18(7), S1–7. https://doi.org/10.4103/1119-3077.170832

- Chima, S. C. (2017). Religion, politics and ethics: moral and ethical dilemmas confronting faith based organizations and Africa in the 21st century–another view. The Asian Conference on Ethics, Religion & Philosophy 2017 Official Conference Proceedings, Art Center Kobe, Kobe, Japan, Identity” & “History, Story & Narrative“. Retrived March 22–25, 2017.

- Cojacaru, C. (2016). My experience is mine to tell: Challenging the abolitionist victimhood framework. Anti-Trafficking Review, 7, 12–38. https://doi.org/10.14197/atr.20121772

- Covidence. (n.d.). Covidence. https://www.covidence.org/

- Gerassi, L. B., & Nichols, A. (2018). Heterogeneous perspectives in coalitions and community-based responses to sex trafficking and commercial sexual exploitation: Implications for practice. Journal of Social Service Research, 44(1), 63–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2017.1401028

- Gerassi, L. B., & Skinkis, S. (2020). An intersectional content analysis of inclusive language and imagery among sex trafficking-related services. Violence and Victims, 35(3), 400–417. https://doi.org/10.1891/VV-D-18-00204

- Gleason, K., & Cockayne, J. (2018). Official development assistance and SDG target 8.7: Measuring aid to address forced labor, modern slavery, human trafficking and child labor. United Nations University Centre for Policy Research, Retrieved September 15, 2019, from http://collections.unu.edu/eserv/UNU:6612/DevelopmentAssistanceandSDGTarget8.7FINALWEB7.pdf

- Global Freedom Network. (2014). A united faith against modern slavery: The joint declaration of religious leaders against modern slavery. www.cdn.walkfree.org

- Global Slavery Index. (2018). Global Slavery Index 2018. https://www.globalslaveryindex.org/resources/downloads/

- Grim, B. J., & Grim, M. E. (2016). The socio-economic contribution of religion to American society: An empirical analysis. Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion, 12(3), 1–31.

- Hassan, S. A., & Khairuldin, W. M. K. F. W. (2020). Research design based on fatwa making process: An exploratory study. International Journal of Higher Education, 9(6), 241–246. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v9n6p241

- Hodge, D. R. (2002). Equipping social workers to address spirituality in practice settings: A model curriculum. Advances in Social Work, 3(2), 85–103. https://doi.org/10.18060/32

- Hodge, D. R. (2012). The conceptual and empirical relationship between spirituality and social justice: Exemplars from diverse faith traditions. Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought, 31(1–2), 32–50. Hodge. https://doi.org/10.1080/15426432.2012.647878

- Hodge, D. R. (2019). Increasing spiritual diversity in social work discourse: A scientific avenue toward more effective mental health service provision. Social Work Education, 38(6), 753–765. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2018.1557630

- Hodge, D. R. (2021). How do trafficking survivors cope? Identifying the general and spiritual coping strategies of men trafficked into the United States. Journal of Social Service Research, 47(2), 155–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2020.1729925

- James, R. (2009). What is distinctive about FBOS? How European FBOs Define and operationalized their faith. Oxford INTRAC Praxis Paper 22. https://www.intrac.org/resources/praxis-paper-22-distinctive-fbos-european-fbos-define-operationalise-faith/

- Joint Learning Initiative on Faith & Local Communities. (n.d.) Joint Learning Initiative on Faith & Local Communities. https://jliflc.com/

- Jones, T. R., & Lutze, F. E. (2016). Anti-human trafficking interagency collaboration in the state of Michigan: An exploratory study. Journal of Human Trafficking, 2(2), 156–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322705.2015.1075342

- Kaag, M., & Saint Lary, M. (2011). The new visibility of religion in the development arena. Christian and Muslim elites’ Engagement with Public Policies in Africa Bulletin de L’apad, (33), 33. https://doi.org/10.4000/apad.4075

- Kagotho, M., & Kagotho, N. (2022). Cultural and religious influences on genetic interventions in sub-Saharan Africa. In R. Drew Smith, C. B. Stephanie, & D. E. Bertis (Eds.), Racialized health, COVID-19, and religious responses (pp. 192–201). Routledge.

- Knight, L., Casassa, K., & Kagotho, N. (2021). Dignity and worth for all: Identifying shared values between social work and Christian faith-based groups’ anti-sex trafficking discourse. Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought, 41(2), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/15426432.2021.2011533

- Knight, L., & Kagotho, N. (2022). On earth and as it is in heaven—there is no sex trafficking in heaven: A qualitative study bringing Christian church leaders’ anti-trafficking viewpoints to trafficking discourse. Religions, 13(1), 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13010065

- Knight, L., Xin, Y., & Mengo, C. (2021). A scoping review of resilience in survivors of human trafficking. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 1524838020985561.

- Lagon, M. P. (2015). Traits of transformative anti-trafficking partners. Journal of Human Trafficking, 1(1), 21–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322705.2015.1008883

- Lucio, R., Rapp McCall, L., & Campion, P. (2020). The creation of a human trafficking course: Interprofessional collaboration from development to delivery. Advances in Social Work, 20(2), 394–408. https://doi.org/10.18060/23679

- Metz, T., & Gaie, J. B. (2010). The African ethic of Ubuntu/Botho: Implications for research on morality. Journal of Moral Education, 39(3), 273–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2010.497609

- Moffatt, K. M., & Oxhandler, H. K. (2018). Religion and spirituality in master of social work education: past, present, and future considerations. Journal of Social Work Education, 54(3), 543–553. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2018.1434443

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArther, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

- Nwogu, V. I. (2014). Anti-trafficking interventions in Nigeria and the principal-agent aid model. Anti-Trafficking Review, 3. https://doi.org/10.14197/atr.20121433

- Panin, A., Tomlinson, M., Skiti, Z., & Rotheram-Borus, M. J. (2021). Soccer, safety and science: Why evidence is key. PEGNet Policy Brief, 2021. No. 23/2020, Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW), Poverty Reduction, Equity and Growth Network (PEGNet), Kiel. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031808

- Pew Research Center, 2018. The Age Gap in Religion Around the World. https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2018/06/13/the-age-gap-in-religion-around-the-world/

- Plambech, S. (2017). God brought you home–deportation as moral governance in the lives of Nigerian sex worker migrants. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 43(13), 2211–2227. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1280386

- Religions against human trafficking (RAHT) Kenya. (n.d.). Religions Against Human Trafficking https://rahtkenya.org/

- Rozario, P. A., & Rosetti, A. L. (2012). “Many helping hands”: A review and analysis of long-term care policies, programs, and practices in Singapore. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 55(7), 641–658. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2012.667524

- Schneider, J. A. (2013). Comparing stewardship across faith-based organizations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 42(3), 517–539. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764012461399

- Schrader, E. M., & Jennifer, M. W. (2012). Music therapy programming at an aftercare center in Cambodia for survivors of child sexual exploitation and rape and their caregivers. Social Work and Christianity, 39(4), 390–406 .

- Sheldon-Sherman, J. A. L. (2012). The missing “p”: Prosecution, prevention, protection, and partnership in the trafficking victims protection act. Penn State Law Review, 117(2), 443–501.

- Spaling, H., & Vander Kooy, K. (2019). Farming god’s way: Agronomy and faith contested. Agriculture and Human Values, 36(3), 411–426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-019-09925-2

- Talitha, K. (n.d.). Talitha Kum End Human Trafficking https://www.talithakum.info/

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C. … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

- T’ruah. (n.d.). T’ruah. https://truah.org/

- Twis, M., & Praetorius, R. (2021). A qualitative interpretive meta-synthesis of evangelical Christian sex trafficking narratives. Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought, 40(2), 189–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/15426432.2020.1871153

- Twis, M. K., & Preble, K. (2020). Intersectional standpoint methodology: Toward theory-driven participatory research on human trafficking. Violence & Victims, 35(3), 418–439. https://doi.org/10.1891/VV-D-18-00208

- Ucnikova, M., & Ucnikova. (2014). OECD and modern slavery: How much aid money is spent to tackle the issue? Anti-Trafficking Review, 3, 133–150. https://doi.org/10.14197/atr.20121437

- Unruh, H. R., & Sider, R. J. (2005). Saving souls, serving society: Understanding the faith factor in church-based social ministry. Oxford University Press.

- US Department of State. (2020). Trafficking in Persons Report 2020. https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/2020-TIP-Report-Complete-062420-FINAL.pdf

- US Department of State. (2021). 2021 Report on International Religious Freedom: Kenya https://www.state.gov/reports/2021-report-on-international-religious-freedom/kenya/

- Vanderwoerd, J. R. (2004). How faith#based social service organizations manage secular pressures associated with government funding. Nonprofit Management & Leadership, 14(3), 239–262.

- Woldehanna, S., Ringheim, K., Murphy, C., Gibson, J., Odyniec, B., Clerisme, C., Uttekar, B. P., Nyamongo, I. K., Savosnick, P., Keikelame, M. J., Im-em, W., Tanga, E. O., Atuyambe, L., & Perry, T. (2005). Faith in action: Examining the role of faith-based organisations in addressing HIV/AIDS—A multi country key informant survey. Global Health Council (GHC).

- Woo, B. D. (2022). The impacts of gender-related factors on the adoption of anti-human trafficking laws in sub-Saharan African countries. SAGE Open, 12(2), 21582440221096128. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440221096128

- World Bank. (2008). The World Bank’s Commitment to HIV/AIDS in Africa. Our Agenda for Action, 2007-2011. The World Bank.

- World Bank. (n.d.). https://www.worldbank.org/en/about/partners/brief/faith-based-organizations

- Zhang, S. X. (2022). Progress and challenges in human trafficking research: Two decades after the Palermo protocol. Journal of Human Trafficking, 8(1), 4–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322705.2021.2019528

- Zhang, S. X., & Cai, L. (2015, December). Counting labour trafficking activities: An empirical attempt at standardized measurement. In K. Kangaspunta (Ed.), Forum on crime and society (Vol. 8, pp. 37–61). United Nations.

- Zimmerman, Y. C. (2010). From Bush to Obama: rethinking sex and religion in the United State’s initiative to combat human trafficking. Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion, 26(1), 79–99. https://doi.org/10.2979/fsr.2010.26.1.79